Quality prescribing for Benzodiazepines and z-drugs: guide for improvement 2024 to 2027

Benzodiazepine and z-drug prescribing continues to slowly reduce across Scotland. Despite this, benzodiazepine and z-drug prescribing remains a challenge. This guide aims to further improve the care of individuals receiving these medicines and promote a holistic approach to person-centred care.

1. Why is this quality prescribing guidance needed?

Background

Benzodiazepines or z-drugs (B-Z) are used for a variety of conditions, including in the treatment of insomnia, and some anxiety disorders, and are commonly prescribed for people experiencing a range of comorbidities. This guide provides general principles to support person-centred review of individuals receiving B-Z, using the 7-Steps process, from their initiation to cessation as well as during the post-treatment follow up period. It includes advice for treatment plans, managed reductions, and stopping where this is appropriate for adults. This advice supports healthcare professionals and others in the appropriate use of B-Z, enabling proactive person-centred reviews, and appropriate continuation, reduction and stopping of B-Z.

This advice is not intended to supersede other prescribing and treatment advice such as NICE, British Association for Psychopharmacology (BAP), Scottish Government Polypharmacy Guidance[3] or the principles outlined in the Realising Realistic Medicines report, but rather to complement them and offer additional practical advice and options for tailoring care to the needs of the individual.

What are the benefits to the person receiving benzodiazepines and/or z-drugs?

This quality prescribing guide is intended to encourage supportive and constructive discussions between individuals and prescribers, to enable shared decision-making when reviewing B-Z and consider the fears and apprehensions associated with reducing or stopping B-Z, tailoring treatment plans to the needs of the individual.

This guidance focuses on quality prescribing to result in improvements in care. The 7-Steps medication review process promotes a shared decision-making approach to medicine reviews and places the individual at the centre, to ensure prescribing is effective and appropriate for them. People will be encouraged to self-manage their condition where appropriate and be asked ‘what matters to you?’[4] to support a holistic approach in line with the Scottish Government’s polypharmacy guidance.3

To ensure outcomes from medication are optimised, and prescribing is appropriate and safe, the 7-Steps medication review process provides a clear structure for both the initiation of new and the review of existing treatments, and places an emphasis on ‘what matters to the individual’? A polypharmacy review (following the 7-Steps approach) should ensure optimal management of conditions. It should include addressing aggravating lifestyle factors and consideration of the most appropriate medication at the right dose, with regular review. The following 7-Steps are intended as a guide to structure the review process.

Step 1: Aim: What matters to the patient?

Step 2: Need: Identify essential drug therapy.

Step 3: Need: Does the patient take unnecessary drug therapy?

Step 4: Effectiveness: Are therapeutic objectives being achieved?

Step 5: Safety: Is the patient at risk of ADRs or suffers actual ADRs?

Step 6: Sustainability: Is therapy cost-effective and environmentally sustainable?

Step 7: Person-centred: Is the person willing and able to take therapy as intended?

The 7-Steps to appropriate polypharmacy demonstrate that the review process is not in fact a linear single event, but cyclical, requiring regular repeat and review (see Figure 2). The circle is centred on what matters to the individual, ensuring they are provided with the right information, tools and resources to make informed decisions about their medicines and treatment options. It should be used at both initiation and review of medicines.

It is important to routinely and proactively monitor and review the ongoing need for B-Z. While the prescribing of B-Z has steadily declined over the last 30 years, and continues to decrease, 1 in 15 (6.8%) adults (≥18 years), and 1 in 11 (8.9%) older adults (≥65 years) in Scotland were prescribed a B-Z in 2020/21.1

The majority of B-Z are prescribed by general practitioners (GPs) in primary care, however some of these prescriptions are initiated and continued on the advice of neurologists, psychiatrists and other specialists, and may result in deliberate or inadvertent long-term use.[5],[6],[7],[8]

For a very small minority of people long-term (≥8weeks) B-Z use may be considered appropriate, for example, in Parkinson’s disease or epilepsy.[9],[10] For the vast majority, long-term use of B-Z raises the risk of harm and runs contrary to current clinical guidelines and drug licensing, as B-Z are licensed for a maximum of four weeks duration.1,5,[11],[12],[13] B-Z also demonstrate limited therapeutic effects for the short-term (e.g. less than two weeks) treatment of insomnia and some anxiety disorders (e.g. generalised anxiety disorder, panic disorder).13,[14],[15]

B-Z use is associated with tolerance, dependence and avoidable drug-related harms. These harms include but are not limited to:

- cognitive dysfunction (confusion, impaired concentration, memory impairment, impaired ability to drive and increased accidents)

- falls, and associated increased risk of hip fractures

- depressive symptoms

- paradoxical effects i.e. disinhibition, anxiety and impulsivity.12,[16]

More recently studies have reported increased mortality associated with B-Z use in a range of populations.[17],[18],[19]

In the short-term (e.g. less than two weeks) B-Z can provide some benefits for insomnia, and some anxiety disorders.14,15 However, they are associated with reducing the effectiveness of psychological therapies and worsening depressive symptoms, causing cognitive dysfunction which may prolong symptoms and slow recovery.12,[20],[21],[22]

The use of benzodiazepines is not recommended for the management of muscle spasm associated with acute low back pain.[23] Benzodiazepines should also not be used in the treatment of sciatica.[24] It is acknowledged that they are used as muscle relaxants in other causes, such as managing muscle spasm pain in palliative care.[25],[26]

B-Z are also associated with a 60-80% increased risk of road traffic accidents,[27],[28] which led the Department of Transport in 2015 to make it ‘illegal in England, Scotland and Wales to drive with legal drugs in your body if it impairs your driving’.[29]

There are concerns regarding the role of B-Z in drug-related deaths.19,[30] This is complicated by more than one drug being used (polydrug use), the use of high B-Z doses (‘mega-dose’) and ageing populations.

There is a lack of evidence that B-Z are routinely diverted from primary care prescriptions. Although small quantities of B-Z have previously been diverted by some individuals, the greater use of instalment dispensing and supervised consumptions can help to reduce this. The electronic transfer of prescriptions in Scotland also reduces the risk of prescriptions being forged or amended. While these methods have been successful in restricting licensed B-Z, it is harder to restrict access to internet and ‘street’ sources of benzodiazepines such as phenazepam, etizolam, alongside those licensed outside of the UK, or other street preparations with varying concentrations of diazepam.19,[31]

While we are limited in the ability to minimise the use of unlicensed and illegally sourced B-Z, proactively reviewing prescribed B-Z use will help to minimise avoidable drug-related harms and optimise an individual’s care.

List 1: Benefits to reviewing benzodiazepines or z-drugs therapy

- Allows assessment of appropriateness and effectiveness of prescribing

- Allows reduction of inappropriate prescribing e.g. long-term

- Minimises risk of avoidable adverse harms associated with their use:

- depression

- emotional blunting

- memory loss and dementia

- paradoxical effects: anxiety, insomnia, aggression, etc.

- falls and hip fractures

- road traffic accidents

- addiction and dependence

- increased mortality risks

- An opportunity to consider more effective methods for treating symptoms

What are the benefits to healthcare professionals?

Prescribers have acknowledged that it can be, ‘…easier to start [psychotropic medicines] than to stop [them].’ [32]

This may be due to a range of perceived and actual barriers, such as a lack of healthcare professionals' confidence, knowledge or skills to support or enable review and discontinuation of psychotropic medicines, such as B-Z and antidepressants.32,[33] Some electronic clinical systems may also be limited in enabling prescribers to proactively identify people for review. The Scottish Therapeutics Utility (STU) has been developed for use in general practice in Scotland, to help identify people who may benefit from a proactive medication review. General practice staff can routinely use STU to identify and plan B-Z review and quality improvement work.

This prescribing guide provides a practical resource and examples of good practice approaches to identifying individuals at risk of medication related harm, reviewing B-Z and supporting the people in our care.

What are the benefits to organisations?

Implementation and use of this guidance may help improve care, clinical outcomes and minimise avoidable medication-related harm.

Included within this document are a range of prescribing indicators and measures to help focus attention and resources on addressing this area. These measures will be of use to individual general practices, general practice clusters, Health and Social Care Partnerships (HSCPs), and health boards. Case studies and examples of what has already been trialled are also included.

Why is reviewing B-Z use important?

B-Z use is associated with tolerance, possible dependence and avoidable drug-related harms. These harms include but are not limited to:

- cognitive dysfunction (confusion, impaired concentration, memory impairment, impaired ability to drive and increased accidents)

- falls and associated increased risk of hip fractures

- depressive symptoms

- paradoxical effects i.e. disinhibition, anxiety and impulsivity12,16

More recently studies have reported increased mortality associated with B-Z use in a range of populations.17-19

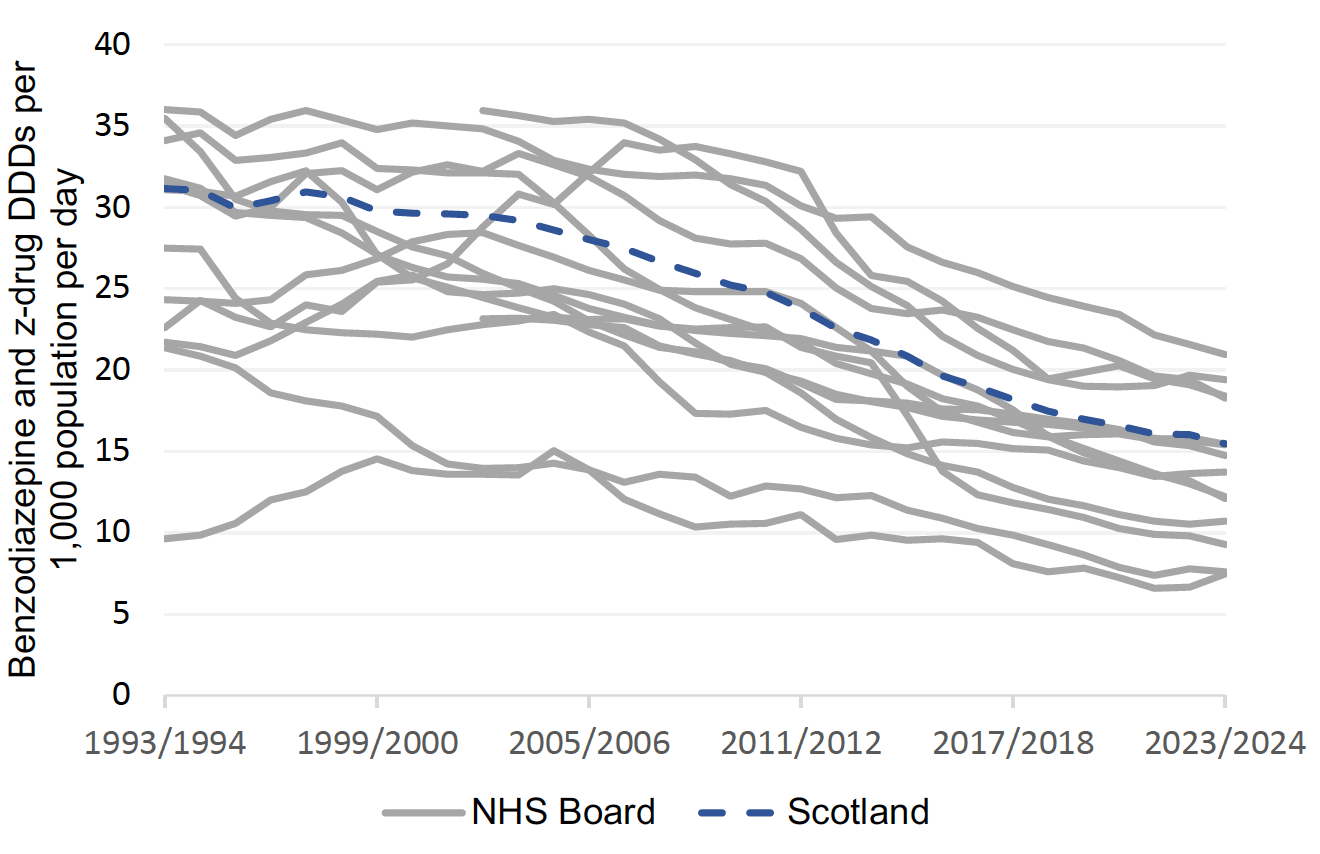

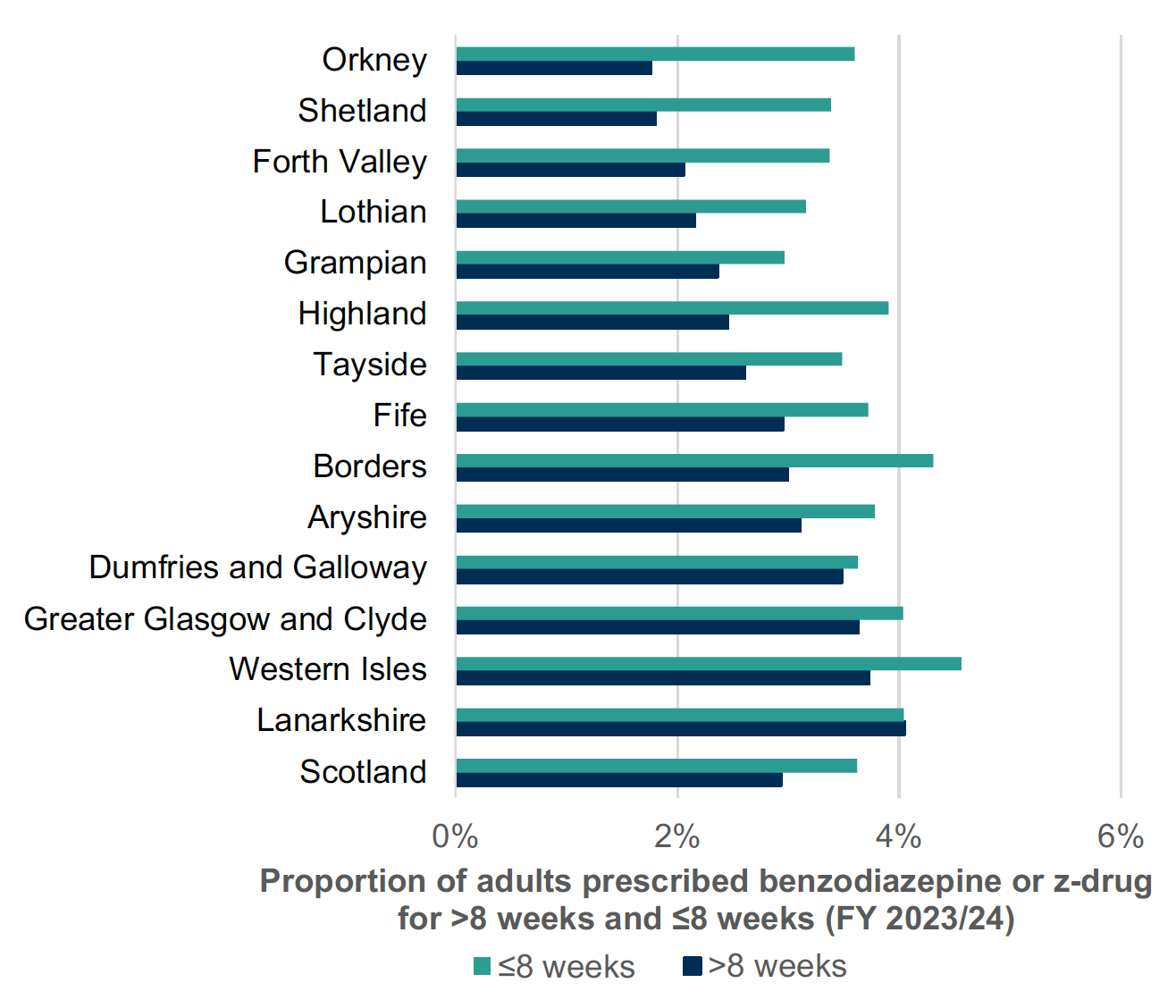

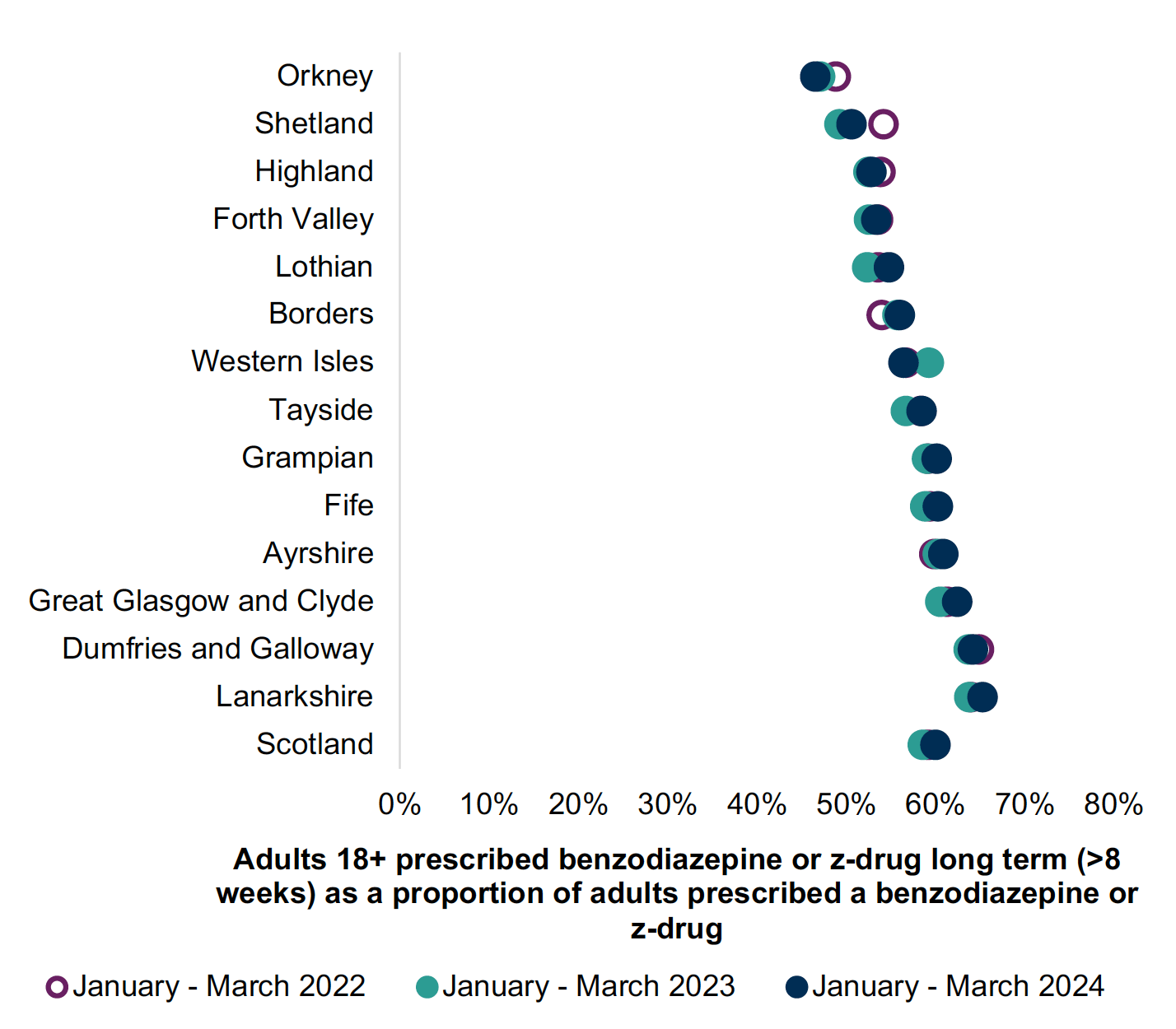

B-Z prescribing has reduced over the years in Scotland (Chart 1). Chart 2 shows less than 6% of adults receiving B-Z in 2023/24. Long-term (≥8 weeks) use remains common with over 40% of adults receiving B-Z remaining on treatment long-term (Chart 3 Jan-March 2024). This is outwith medicine licensing and runs contrary to current guidelines and prescribing advice.5,13,15

Current NICE guidance advises that prescribers ‘do not offer a benzodiazepine for the treatment of Generalised Anxiety Disorder (GAD) in primary or secondary care, except as a short-term measure during crises’.15 However, where their use is considered appropriate for the short-term treatment of insomnia or anxiety disorders their use should be limited to, for example, less than two weeks on an ‘as required’ basis.14,15

Proactively reviewing B-Z prescribing and their use creates an opportunity to reduce and stop inappropriate medicines and has been shown to be effective. [34], [35],[36], [37], [38] The use of such proactive reviews across Scotland has helped practices and health boards reduce inappropriate B-Z use, see Charts 2 and 3.

Environmental impact

The healthcare industry is increasingly asked to account for the negative environmental impact generated through providing medical care.

In Scotland, every 10 days a 10-tonne truck of medicines waste is transported for incineration. There are associated costs with incineration; travel costs and environment impact (see Figure 3 below). This is in addition to the direct costs of unused medication.

Graphic text below:

Medicine waste disposal in Scotland

- 365 tonnes of waste are incinerated every year

- this disposal alone costs £0.25 million a year

- with a CO2 equivalence of 28 car journeys around the world a year (700,000 miles)

There are many factors which contribute to medicines waste and a Department of Health and Social Care report in September 2021[39] showed that over prescribing is commonplace, accounting for at least 10% of all prescribed medications.

This guidance supports reducing inappropriate prescribing by recommending person-centred medicine reviews; providing guidance and support for clinicians and promoting the use of non-pharmacological alternatives where available and effective. This may involve physical and social activities, lifestyle change and regular medicine reviews for those with long-term health conditions.

The Royal Pharmaceutical Society policy, ‘Pharmacy’s role in climate action and sustainable healthcare’,[40] identifies medicines as contributing 25% of carbon emissions in the NHS.

This can be reduced by:

- improving prescribing and medicines use

- tackling medicines waste

- preventing ill health; and

- improving infrastructure and ways of working.

The Royal College of General Practitioners[41] has identified that prescribing accounts for over 60% of general practice’s carbon footprint.

Reduction of medicines waste can be achieved by ensuring appropriate prescribing and initiation of medicines, regular person-centred medication reviews to ensure continued effectiveness and deprescribing medicines where appropriate using the 7-Steps process.

Reducing waste from medicines has a double carbon and environmental benefit by:

- reducing upstream emissions, e.g. those associated with distribution, and

- downstream emissions, where fewer medicines need to be disposed of.

Medicines that are disposed of in general waste, poured down the sink or flushed down the toilet, increase the risk of environmental harm. Residues from medicines which are unused, not properly disposed of, or from those that pass through the body, can be found in water, soil and sludge and in organisms at all stages of their lifecycles.[42]

Unused or unwanted medicines should be returned to community pharmacy for safe disposal or recycling where available.

The Sustainable Markets Initiative (SMI) established in 2020 identify seven levers to reduce carbon emissions in care pathways:[43]

1. Decarbonising facilities and fleets

2. Preventing disease onset

3. Diagnosing early

4. Optimising disease management

5. Improving the efficiency of interventions

6. Delivering care remotely or closer to home when appropriate – digital innovations

7. Using lower-emission treatments where available

Pharmaceuticals in the water environment

The Royal Pharmaceutical Society’s Sustainability Policies40 also point to the occurrence of pharmaceuticals in the water environment. Every oral dose of a medicine taken is excreted unchanged or converted to a metabolite with 30-100% entering our wastewater system which cannot effectively remove all traces. The occurrence of pharmaceuticals in the environment is of global concern and the extent of the risks and impacts on human health and biota is growing. There is already evidence that they can affect aquatic wildlife, increase microbial resistance and enter the human food chain.

Benzodiazepines are not fully metabolised by the human body and are excreted into wastewater systems.[44] They fail to degrade quickly in surface waters (i.e. rivers) and their persistent nature can have a negative impact on aquatic ecosystems and wildlife. Benzodiazepines can alter the social behaviour and feeding rates of certain species of European freshwater fish,[45],[46] and Diazepam can decrease the growth rate of some invertebrates and increase mortality rates of fish species, even at low environmental levels.[47],[48] Oxazepam has also shown to alter the reproductive ability of European species of freshwater snails.44

While the direct impacts of pharmaceuticals in the environment through consumption of plant-derived food, meat, and drinking water is predicted to have negligible to low risk on human health, its chronic effects should be taken into consideration, as pharmaceutical substances have the potential to accumulate in plants and soil invertebrates.[49],[50],[51]

Reduction of medicines waste and harm can be achieved by ensuring appropriate prescribing and effective use of medicines, regular person-centred medication reviews and deprescribing where this is appropriate.

Contact

Email: EPandT@gov.scot

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback