Quality prescribing for Benzodiazepines and z-drugs: guide for improvement 2024 to 2027

Benzodiazepine and z-drug prescribing continues to slowly reduce across Scotland. Despite this, benzodiazepine and z-drug prescribing remains a challenge. This guide aims to further improve the care of individuals receiving these medicines and promote a holistic approach to person-centred care.

2. Recommendations and guidance for healthcare professionals

Health Care professionals should:

Consider non-pharmacological options, including psychosocial and/or psychological interventions where appropriate

Non-medicalised[52],[53],[54]

- exercise and regular physical activity e.g. 30-minute walks

- debt advice and/or money management e.g. seeking advice from appropriate agencies such as Citizens Advice

- hobbies and interests e.g. gardening, crafts, etc

- ensuring a good work-life balance

- lunch clubs and other activities which may help to reduce social isolation

- discussing problems, where appropriate, with a close friend or confidante that is willing and able to listen

Psychosocial and psychological Interventions

The Psychological Therapies Matrix (2015) outlines a matched care approach to support the safe and effective delivery of evidence-based psychological interventions. Both the Matrix and clinical guidelines advocating decisions regarding psychological interventions should be based on a comprehensive assessment of need and consider suitability, individual preference, availability of trained practitioners and be culturally appropriate.15,58,59 This matched care model considers ‘high volume’ interventions and low intensity interventions for mild to moderate symptoms.

For those presenting with more complex presentations, high intensity and highly specialist interventions, delivered by practitioners with additional competences and access to appropriate supervision are outlined. The Matrix acknowledges those in general practice and primary care regularly identify and support those presenting with psychological issues and mental health disorders and are therefore in a position to provide support for low intensity interventions and referral to specialist mental health services where indicated.

A range of activities can be helpful for people with common mental health and pain conditions. Decisions for signposting and/or referral for psychological interventions should be informed by a comprehensive assessment and shared understanding of the reasons for the underlying anxiety and/or sleep problem.

Some of the following may be useful for people with anxiety and should be considered and discussed before initiating a B-Z for a severe crisis, or continuing a B-Z. Where appropriate and available Community Link Workers may be able to support and enable individuals to access some of these options.

Low Intensity Interventions

Low intensity interventions for mild to moderate symptoms of insomnia or anxiety include guided self-help and computerised Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (cCBT).[55] Psychoeducation regarding the specific condition (anxiety, insomnia) can support self-management. A range of evidence-based cCBT programmes and telephone supports are available to support general mental wellbeing, sleep problems (including insomnia) and mild to moderate symptoms of anxiety. These programmes can be accessed via NHS Inform (Mental Health). Please refer to Appendix 2 for a detailed description and resource links. NICE provide additional recommendations on sleep hygiene for insomnia.[56]

High Intensity and Highly Specialist interventions

For individuals who present with moderate to severe symptoms of anxiety and more complex presentations, including within the context of co-occurring substance use, a referral for High Intensity or Highly Specialist Interventions (including Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (CBT) is indicated. These interventions are usually delivered within NHS, or non-NHS, secondary care or specialist services.

(Non-NHS services: ensure any non-NHS practitioners providing psychological therapies are registered with appropriate professional bodies e.g. Health and Care Professions Council, British Association of Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, British Association of Counselling and Psychotherapy.)

Follow a person-centred approach to initiating and limiting B-Z supply:

In order to provide consistency and continuity for all individuals, prescribers should develop a benzodiazepine prescribing policy for use in their setting. A holistic assessment that includes a discussion of the risks, benefits and limitations of prescribing should inform decisions to initiate B-Z, independent of what condition is being treated. Please consider the following:

Assess risk, benefits and limitations, independent of what condition is being treated, see List 1.

Condition |

Evidence summary |

|---|---|

Insomnia |

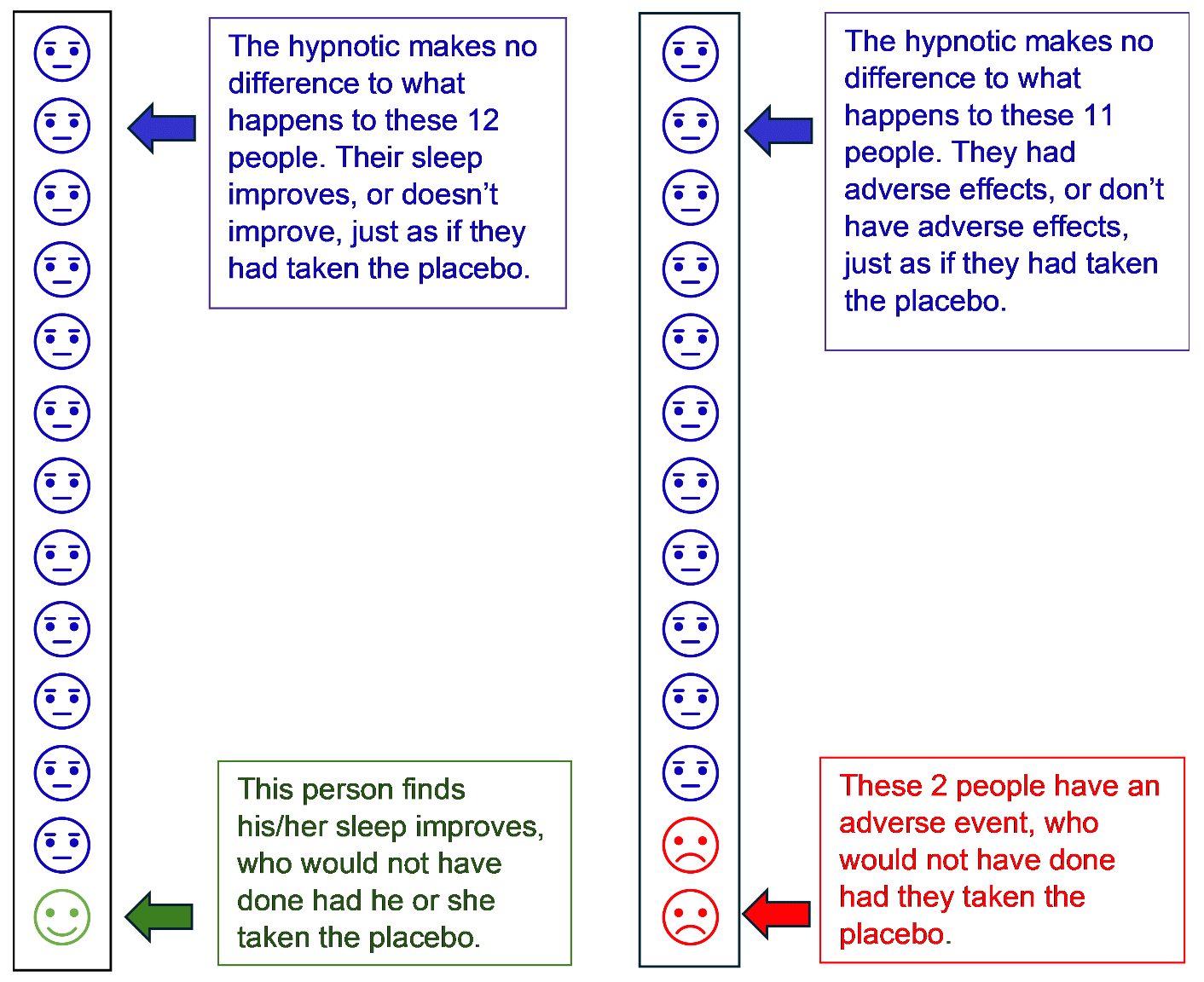

The majority of studies have been for treatment of seven days or less of therapy. The effects were small, with an increased risk of adverse effects; the number needed to treat for improved sleep quality was 13 and the number needed to harm for any adverse event was 6, Figure 4.[57] Adverse events were defined as cognitive (memory loss, confusion, disorientation); psychomotor (reports of dizziness, loss of balance, or falls); and morning hangover effects (residual morning sedation). |

Anxiety disorders |

Benzodiazepines are not recommended for the routine treatment of general anxiety disorder (GAD), panic disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or panic disorder.14,15,[58] A stepped-care approach including psychological treatment and/or self-help is advised. Pharmacological treatment, if assessed as being appropriate, should be with a selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitor e.g. GAD: step 3 where there is marked functional impairment, or that has not improved after step 2.14,15,58 |

Depression |

B-Z are not recommended for the treatment of depression[59] or the treatment of general anxiety disorder.15 It is known that regular B-Z use is associated with reducing the effectiveness of psychological therapies (interfering with new memory formation), worsening depressive symptoms, and cognitive dysfunction which may prolong symptoms and slow recovery.12,20,22 It is advised that co-prescribing B-Z with antidepressants should be avoided wherever possible. A recent Cochrane Review indicated that the evidence for benefit was marginal and there was no difference in dropouts due to any reason, between combined therapy (antidepressant plus B-Z) and antidepressants alone in the first two weeks of treatment.[60] |

Low back pain and sciatica |

NICE recommends ‘do not offer gabapentinoids, other antiepileptics, oral corticosteroids or benzodiazepines for management of sciatica, as there is no overall evidence of benefit and there is evidence of harm’.24 |

Chronic pain |

NICE recommends ‘do not initiate benzodiazepines to manage chronic primary pain in people aged 16 years and over’.[61] |

Note: short-term use one to two weeks.

- Discuss individual and prescriber expectations before initiation of new prescribing. Review medication using the 7-Steps process. Consider stepped-care and watchful-waiting for common mental health conditions. Highlight effective non-pharmacological interventions where appropriate (e.g. physical activity, self-help). Outline drug limitations e.g. marginal effects during crises but adverse effects are common.

- Provide appropriate information about the condition (NHS Inform website), B-Z treatment and stopping. The Choice and Medications website contains a variety of information and leaflets which may be helpful.

- Plan and agree follow-up in relation to the condition being treated.

- Review effectiveness, tolerability and adherence on an ongoing basis, and where appropriate reduce the number and doses of medicines to minimise avoidable adverse effects and optimise adherence.

Note: Population: adults (≥60 years old) prescribed a benzodiazepine or z-drug for insomnia; 18 (75%) of studies meeting inclusion criteria were for ≤14 days of treatment.57

Collaboratively develop a clear management plan with the individual, and/or carer(s) if appropriate

Aim to develop mutually supportive and constructive discussions between individuals and prescribers when reviewing B-Z and their ongoing need. Where appropriate consider the fears and apprehensions associated with reducing/stopping B-Z and tailoring treatment to the individual’s needs. Where there may be health literacy issues, ensure that enough time is given for the consultation.

A stepped-care approach should be considered to tailor the most appropriate intervention to the individual’s needs such as self-help, non-pharmacological with or without pharmacological treatments.

Discuss realistic expectations and set review dates which can be coded for recall and follow-up.

Consider risk of cumulative toxicity in relation to co-prescribed medicines. See Chart 4 below or in the Polypharmacy Guidance.3

| BNF Chapter | ADR Medication | F | C | UR | CNS | B | H F | Br | CV | R | H | R I | Hypo | Hyp | SS | A C G |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | H2 Blocker | Y | Y | - |

- | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Laxatives | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | Y | - | - | - | |

| Loperamide | Y | Y | Y | Y | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Prochlorperazine etc a | Y | - | - | Y | - | - | Y | Y | - | - | - | Y | - | - | Y | |

| Metoclopramide | Y | - | - | Y | - | - | Y | Y | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| 2 | ACE/ARB | Y | Y | - | - | - | - | - | Y | Y | - | Y | - | Y | - | - |

| Thiazide diuretics | Y | Y | - | Y | - | - | - | - | - | - | Y | Y | - | - | - | |

| Loop diuretics | Y | Y | - | - | - | - | - | Y | - | - | Y | Y | - | - | - | |

| Amiloridef/triamterene | Y | Y | - | Y | Y | - | - | - | Y | - | Y | - | Y | - | Y | |

| Spironolactone | Y | - | - | Y | - | - | - | - | - | - | Y | - | Y | - | - | |

| Beta-blocker | Y | Y | - | - | - | Y | Y | - | Y | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| CCB (dihydropyridine) | Y | Y | - | Y | - | - | - | Y | Y | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| CCB (verapamil/ diltiazem) | Y | Y | - | - | - | Y | Y | Y | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Nitrates and nicorandil | Y | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Digoxin | Y | - | - | - | - | - | Y | Y | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| 3 | Theophylline | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | Y | - | - | - | Y | - | - | - |

| Oral steroids | Y | - | - | Y | Y | Y | - | - | - | - | - | Y | - | - | Y | |

| 4 | Opiates | Y | Y | Y | Y | - | - | - | - | Y | - | - | - | - | Y | - |

| Benzodiazepines | Y | Y | Y | - | - | - | - | Y | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| zSedative antihistaminesd | Y | Y | Y | Y | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| H1 Blockers | Y | Y | Y | Y | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Antipsychoticse | Y | Y | Y | Y | - | - | - | Y | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| SSRI and related | - | - | Y | Y | Y | - | - | Y | - | - | - | - | - | Y | - | |

| TCAsc | Y | Y | Y | Y | - | Y | - | Y | - | Y | - | - | - | Y | Y | |

| MAO inhibitors | - | Y | Y | Y | - | - | Y | Y | - | - | - | - | - | Y | Y | |

| 5 | Antibiotics/ Antifungals | - | - | - | - | - | Y | - | - | - | - | Y | - | Y | - | - |

| 6 | Sulfonylureas, gliptins, glinides | Y | Y | - | - | - | - | - | - | Y | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Pioglitazone | Y | - | - | - | - | Y | - | - | Y | Y | - | - | - | - | - | |

| 7 | Urinary antispasmodics | Y | Y | Y | Y | - | - | - | Y | - | Y | - | - | - | - | Y |

| Dosulepinb | Y | Y | Y | Y | - | - | - | Y | - | Y | - | - | - | - | Y | |

| Alpha blocker | Y | - | - | Y | - | - | - | Y | Y | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| 10 | NSAIDs | - | - | - | - | Y | - | - | Y | Y | - | Y | - | - | - | - |

Key: F - Falls and fractures; C – Constipation; UR - Urinary retention; CNS – CNS Depression; B – Bleeding; HF - Heart failure; Br – Bradycardia; CV - CV events; R – Respiratory; H – Hypoglycaemia; RI - Renal injury; Hypo – Hypokalaemia; Hype – Hyperkalaemia; SS - Serotonin syndrome; ACG – Angle Closure Angle Glaucoma

a. strong anticholinergics are: dimenhydrinate, scopolamine, dicyclomine, hyoscyamine, propantheline;

b. strong anticholinergics are: tolterodine, oxybutynin, flavoxate;

c. strong anticholinergics are: amitriptyline, desipramine, doxepine, imipramine, nortriptyline, trimipramine, protriptyline;

d. strong anticholinergics are: promethazine;

e. strong anticholinergics are: diphenhydramine, clemastine, chlorphenamine, hydroxyzine.

f. Amiloride side effect frequency unknown

Ensure individuals are assessed and coded in primary care for the condition being treated

Appropriately coding of individuals’ records may enable and support proactive medication reviews and follow-up in the short- and long-term in primary and secondary care, as prescribers have indicated that:

‘...patients can get lost in the system, and that systems which adequately prompt [psychotropic] medication reviews would be useful in broaching discontinuation with patients.38

Although current guidelines do not recommend the routine use of B-Z for the treatment or management of anxiety disorders,15,58,59 appropriate coding of an individual’s electronic clinical records may help to identify people for review and routine follow-up. For example, using Read Coding:

- Anxiety disorder such as GAD (E2002), post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD, Eu431)

- For a polypharmacy review, if reviewing existing treatment prior to initiation of B-Z medicines, use read code 8B31B Polypharmacy medication review.

- Where the condition has resolved and the B-Z has been stopped, please use the appropriate Read Code e.g. anxiety resolved (2126J). (Other Read Codes for resolution of symptoms are not currently available on general practice systems)

Boards and HSCPs should:

Consider the prescribing advice within this document alongside local prescribing and clinical data; positions and trends, to plan, resource and drive quality improvement and prescribing initiatives.

Nominate local leads/champions – one medical and one within, or with strong links to, medicines management teams or equivalent – to drive delivery and recommendations within this document.

Consider and engage a whole system approach to delivering quality improvements in prescribing:

- Ensure primary and secondary care are informed, to support continuity of care and overall goals of reviewing and minimising inappropriate prescribing. Recognise the significant influence of secondary care in prescribing behaviour. HSCPs should consider locality work targeting B-Z prescribing.

- Work with third sector (non-medicalised) organisations to further develop and support the capacity for self-management.

- Develop capacity to support individuals and services.

Hospitals

Where B-Z cannot be stopped before discharge, secondary care should establish and communicate a reduction plan for B-Z prescriptions started in hospital.

Where appropriate, hospitals should develop and implement a ‘no hypnotic on discharge policy’ for B-Z initiated in hospital.

Care homes

Individuals within care homes should be identified for proactive review to ensure that any B-Z medicines prescribed have an appropriate indication and are prescribed at the lowest therapeutic dose to achieve the desired effect and reduce the risk of harm. Sleep disturbance affects 38% of care home residents living with dementia,[62] who are often treated with medication where non-pharmacological interventions may be safer and effective.[63],[64] Despite the challenges to implementation of non-pharmacological interventions, these should be considered as alternatives to prescribing in care homes where appropriate.

General practice clusters

Engage with local prescribing support teams, who have a wealth of experience improving the quality of prescribing through use of local and national measures, datasets and tools.

Consider developing and implementing general practice or cluster policies, that include key principles (see Appendix 6). This may help to reduce ‘doctor shopping’ within localities as all practices will be applying the same policy.

Contact

Email: EPandT@gov.scot

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback