Respiratory conditions - quality prescribing strategy: improvement guide 2024 to 2027

Respiratory conditions are a major contributor to ill health, disability, and premature death – the most common conditions being asthma and COPD. This quality prescribing guide is designed to ensure people with respiratory conditions are at the centre of their treatment.

10. Environmental impact of inhalers

NHS Scotland has committed to be a net zero greenhouse gas emissions organisation by 2040.[8]

It is estimated that NHS Scotland emissions due to inhaler propellant was 81,072 tonnes of carbon dioxide (CO2) equivalent in 2022/23. This is approximately the same as 81,000 people flying from London to New York. Approximately 3% of the carbon footprint of NHS Scotland results from the use of metered dose inhalers (pMDI), more than from NHS fleet and waste combined.[74],[8] Salbutamol alone accounts for two thirds of the total carbon footprint from pMDIs.29

Summary of recommendations for environmental considerations of respiratory prescribing

Our recommendations are as follows:

- promotion of person-centred reviews to optimise disease control and ensure quality prescribing in line with national guidance

- prioritise review of people with asthma who are over-reliant on SABA inhalers, defined as ordering more than three inhalers per year (see asthma chapter). Those on six or more should be targeted first

- streamline devices for patients, avoiding multiple device use where possible

- review separate inhalers where a combination inhaler device would be possible

- review individuals prescribed SABA alone, check diagnosis and if appropriate consider a low GWP inhaler

- update local formularies to highlight and promote inhalers with lower CO2 emissions

- use ScriptSwitch in GP Practices to promote better asthma care and environmental messages e.g.

- highlighting SABA overuse

- prescribe low volume cannister Salbutamol pMDI with lower GWP

- raise public awareness to promote good asthma care and the environmental impact of respiratory prescribing

- utilise resources to support patients and clinicians in environmentally friendly and sustainable prescribing (see Appendix 1)

For new patients:

- use inhalers with low global warming potential where they are as equally effective.

- where there is no alternative to a pMDIs, lower volume HFA 134a pMDIs should be used in preference to large volume or HFA 227ea pMDIs

For existing patients:

- switch to DPI or SMI if appropriate, following a patient review. We do not recommend a blanket switch

- consider switch to DPI inhalers for patients with asthma who are interested and: have an adequate inspiratory flow. If there is concern regarding inspiratory ability due to age or frailty, it can be checked using an inspiratory flow device, such as placebo whistles or In-check® device

Environmental impact of inhalers

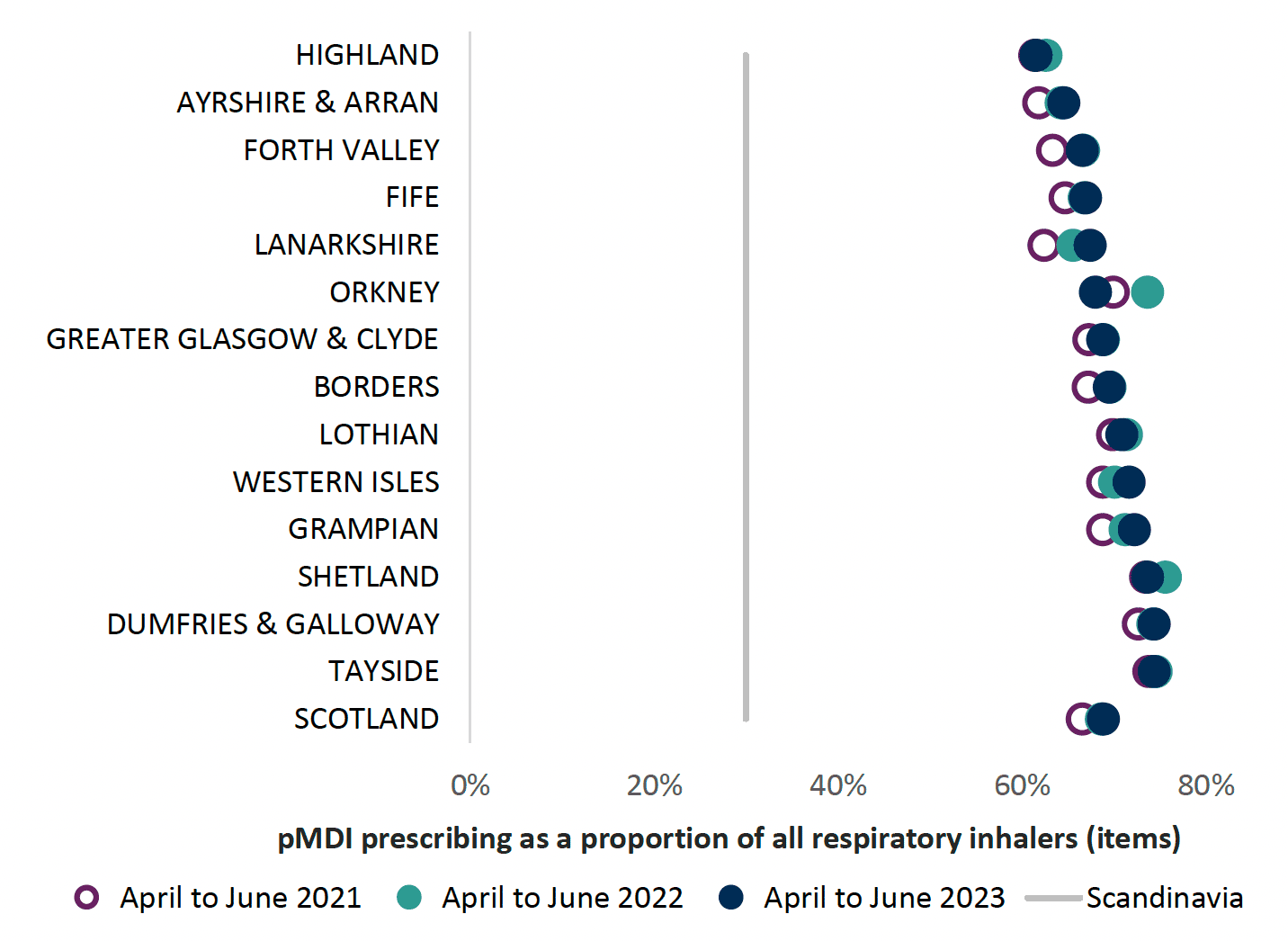

Prescribing data for the year 2020/2021 shows that in NHS Scotland 68% inhalers dispensed were pMDI and 32% were dry powder inhalers (DPI) or soft mist inhalers. The UK has a high proportion of pMDI use (70%) compared with the rest of Europe (< 50%) and Scandinavia (10–30%).[75] Figures from Scandinavia show a lower rate of deaths.[30]

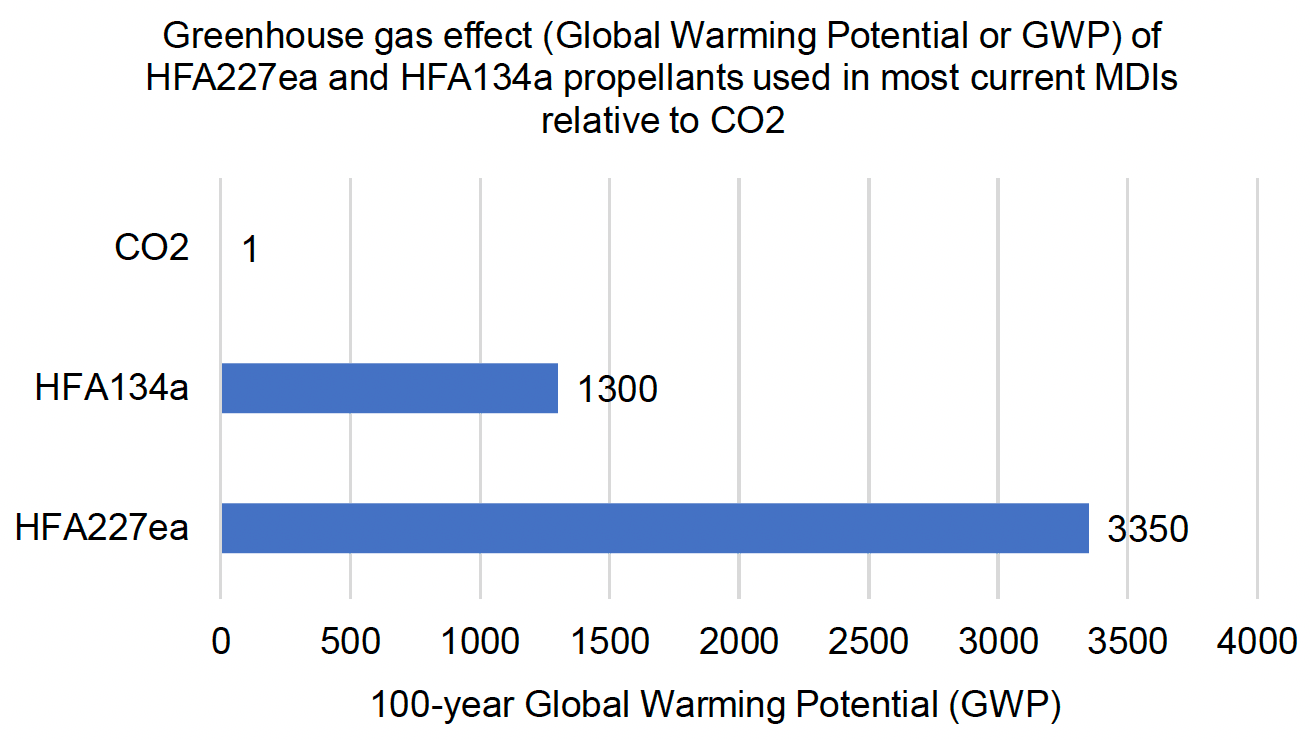

Healthcare professionals should be aware of the differences in environmental impact and global warming potential of metered dose inhalers (pMDI), dry powder inhalers (DPI) and soft mist inhalers (SMI). The hydrofluoroalkane (HFAs) propellant gases used in pMDIs, HFA 134a and HFA 227ea, are potent greenhouse gases which are respectively 1300 and 3350 times more potent than CO2.[76] DPI inhalers have significantly less global warming potential.[77]

A UK based post-hoc analysis has demonstrated that patients can be changed from an MDI to a DPI without loss of asthma control.[78] Delivery of SABAs via a pMDI and spacer or a DPI leads to a similar improvement in lung function as delivery via nebulizer.[26], [79] Individuals are generally able to generate PIFR of 30 L/min with any device and most can reach 60 L/min with medium-low resistance devices even during exacerbations.[79]

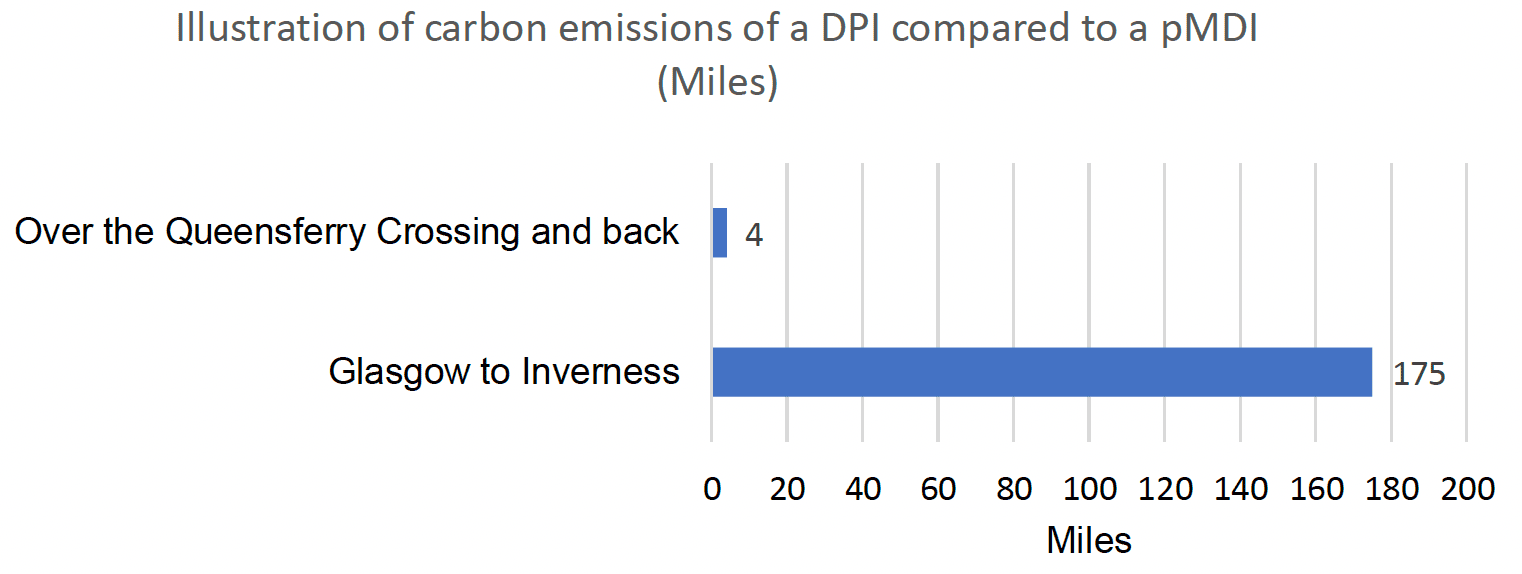

Figure 8 highlights the approximate difference in greenhouse gas emissions comparing a Ventolin® Evohaler® with Ventolin® Accuhaler® or salbutamol Easyhaler® and illustrates the equivalent carbon emissions from driving a car emitting 180g CO2/Km. Many people recognise the carbon emissions from driving and therefore this can be a helpful comparison. The calculation is based on an average of 12g of propellant per MDI. There are currently two types of propellants used, HFA-134a and HFA-227ea which have a global warming potential (GWP) of 1300 or 3350 times greater than CO2.The carbon emissions were estimated by multiplying the estimated weight of HFA propellant by its GWP. We have assumed that DPIs have zero emissions (due to absence of propellant).

Equivalent car exhaust emissions CO2 emissions from a Ventolin Evohaler (containing 100 x 2 puff doses) and a Ventolin Accuhaler (60 x 1 puff doses) or Salbutamol Easyhaler (200 x 1 puff doses). Assumes car achieves 180g CO2/Km.

Individuals may be interested in the carbon footprint of their inhaler treatment which should be considered during review. Changes should only be made if effectiveness, safety or adherence is not compromised and this should be managed on a case-by-case basis, using a shared decision-making approach. Changes should not be made without consulting the patient - the NICE: inhalers for asthma prescribing decision aid can be a useful aid for this process.[36]

Switching inhalers from MDIs to DPIs could result in the same amount of carbon saving as planting seven trees. (Based on one year of treatment in a person with good control of asthma, using no more than three doses of SABA per week and a regular preventer).

The most environmentally friendly inhaler is the one that the patient can, will and does use correctly

The most important factor in choosing an inhaler device is that the individual can use the inhaler properly.[6] It is essential that reviews are timely to ensure control of their condition is maximised, and inhalers are prescribed and used appropriately, checking adherence to therapy.

Poor control of asthma leads to over-reliance on reliever inhalers and Salbutamol MDI alone accounts for 66% of the total carbon footprint from inhalers.[29] Through clinician review and improved management of asthma and COPD, we can improve outcomes for patients, reduce salbutamol use and reduce carbon emissions from inhalers (see Chapter 1).

Good asthma control is better for your patient and the environment

Local formularies should be updated to highlight and promote lower CO2 emission inhalers and ScriptSwitch can be used to promote environmentally friendly prescribing messages, particularly when prescribing for new patients.

Health Boards should consider how to raise public awareness to promote environmentally friendly prescribing and encourage individuals to ask prescribers about this at their review.

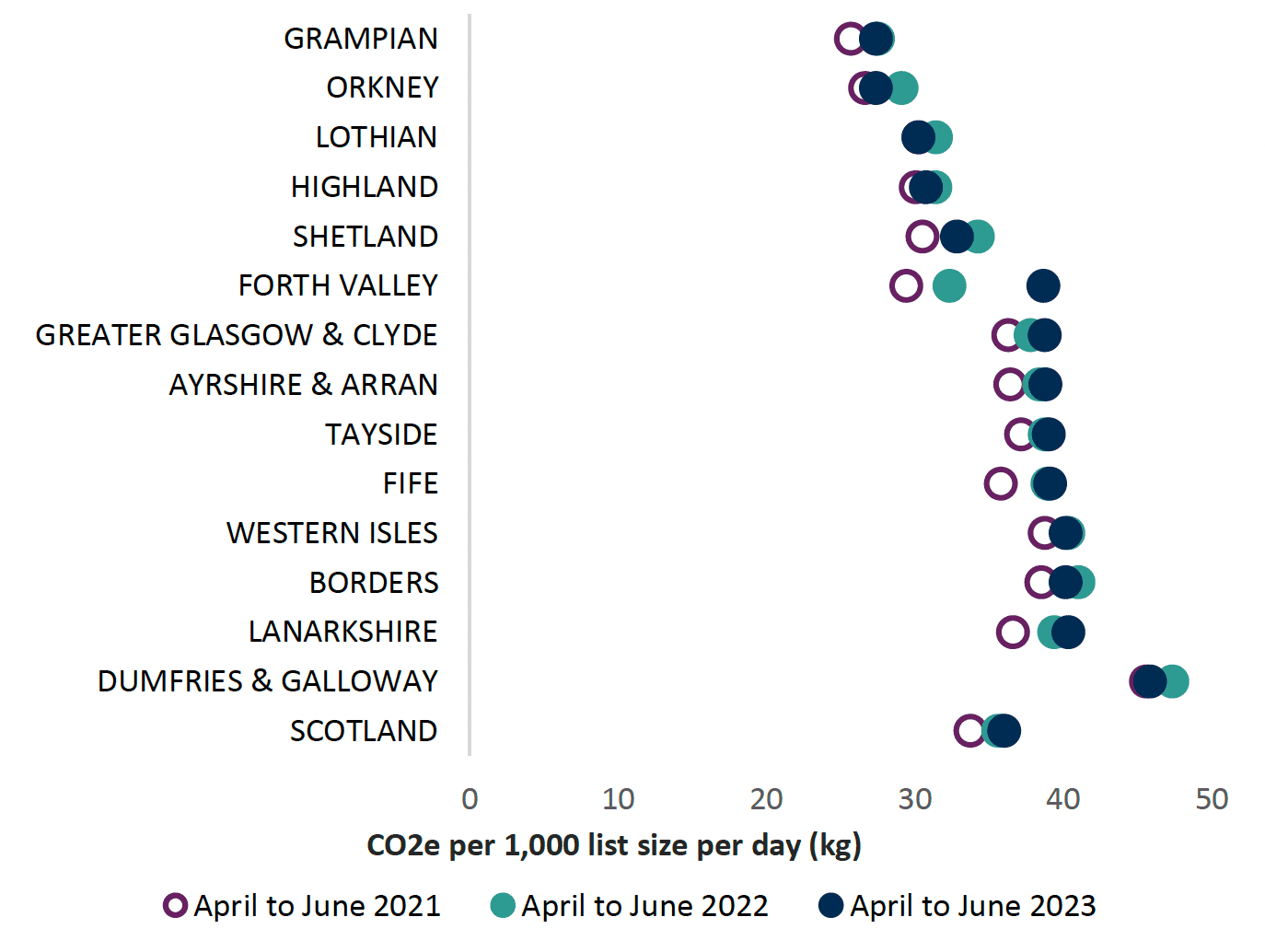

CO2 emissions in Scotland

An ambitious target of 70% reduction in CO2 emissions from inhalers by 2028 has been set, as NHS Scotland works towards the commitment of net zero emissions by 2040. The 70% reduction has been split into biennial targets indicated by the grey lines on Chart 14 below:

- a 25% reduction of CO2 emissions is required by the end of 2024

- a 50% reduction of CO2 emissions is required by 2026 and

- a 70% reduction by end of 2028

Prescribing indicators have been developed, as described below, to support achievement of the target.

Chart 14 below shows the CO2 equivalent emissions of inhaler propellant for each Health Board. The calculation is based on an average of 12g of propellant per MDI. There are currently two types of propellants used, HFA-134a and HFA-227ea which have a global warming potential (GWP) of 1300 or 3350 times greater than CO2.The carbon emissions were estimated by multiplying the estimated weight of HFA propellant by its GWP. We have assumed that DPIs have zero emissions.[8] Other factors such as manufacturing process, plastics used and recycling potential are not included in these calculations.

Rationale for CO2 emission target

CO2 has a 100- year global warming potential (GWP) of one. pMDI’s contain the propellants HFA 134a or HFA 227ea which have 1300 and 3320 higher GWP respectively then CO2. Figure 9 below highlights the differences in GWP of the propellants.[77] All dry powder inhalers and soft mist inhalers have considerably lower GWP than pMDIs.

New propellants such as HFA 152a and HFO-1234ze will have a low global warming potential and reduce the carbon footprint of pMDIs by at least 90%.[80],[81] There is ongoing development of new propellants within the pharmaceutical sector, predicted to be available by 2025.

PrescQIPP data is available which estimates an indicative total CO2 emission (g) for each inhaler based on the life cycle including manufacturing process, plastics used, recyclable material and propellants contained.[82] A lot of these factors are subject to change, so this guide has focussed on CO2 emissions of the propellant initially to allow NHS Scotland to meet the CO2 reduction targets set. It is acknowledged that recycling of inhalers within NHS Scotland needs to improve and at present it is harder to recycle a DPI. Table 6 gives examples of inhalers and the respective GWP.

| SMI (soft mist inhaler) Very Low GWP | DPI Very low GWP | HFA 152a containing MDI inhalers due 2025 Very low GWP | HFA 134a containing pMDI High GWP | HFA 134a containing pMDI (large volume cannister) Very high GWP | HFA 227ea containing pMDI Very high GWP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spiriva® Respimat ® | Accuhaler ® | MDI inhalers containing HFA 152a or other propellants due 2025 | Salamol® Easibreathe ® pMDI | Ventolin® pMDI | Flutiform® pMDI |

| Spiolto® Respimat ® | Easyhaler® | Clenil ® pMDI | Symbicort® pMDI | ||

| Ellipta ® | Seretide ® pMDI |

Environmental prescribing issues to consider

For new patients

Opportunities for environmentally sustainable prescribing should be considered when prescribing inhalers for a new patient.

As there are significant differences in the global warming potential of different pMDIs, the following should be considered:

- use inhalers with a low global warming potential when they are as equally effective6

- where there is no alternative to a pMDI, lower volume HFA134a pMDI should be used in preference to large volume or HFA227ea pMDIs[6]

- prescribing decisions should be based on patient preference and ability to use the device. Ensure inhaler technique is taught and inspiratory flow may be assessed using an In-check® device

- patient should be counselled on expectations of treatment, signs of poor control and importance of adherence and attendance at review

- for patients with asthma use NICE asthma inhalers and the environment patient decision aid

For existing patients

As part of a person-centred review when optimising treatment, consider the opportunity for using a more carbon friendly inhaler. During the review, prescribers should use their judgement and consider the following:

- aim for the lowest GWP where possible, for example, a DPI or SMI

- switching stable patients from pMDI to DPI for SABA inhalers, where the individual is co-prescribed a DPI combination inhaler[6]

- using combination inhalers in place of separate inhalers to reduce the quantity of inhalers and GWP

- poor control may be due to poor inhaler technique, and if this is a pMDI, then a change to a DPI or SMI may help improve control. Ensure that inhaler technique is taught and checked

See Appendix 2 for consideration of when a DPI may not be suitable.

Prescribing Indicators to support reduction of CO2 emissions from inhalers

Proportion of pMDIs versus all inhalers

Chart 15 shows the proportion of pMDIs dispensed as a proportion of all other inhalers (including dry powder inhalers and soft mist inhalers). As detailed above, the UK has a high proportion of pMDI use (70%) compared with the rest of Europe (< 50%) and Scandinavia (10–30%).[75] The grey line on the chart indicates the Scandinavian level of pMDI prescribing at 30% as a comparator. Figures from Scandinavia do not show a higher rate of uncontrolled disease or deaths.[30]

There may be opportunities to discuss inhaler choices with patients at their regular respiratory review. Changes to inhaler type should only take place in discussion with the patient but may be an opportunity to reduce carbon emissions where disease control will not be compromised. An inhaler selection decision aid has been developed to support this guidance, based on Appendix 2, and is incorporated into the Respiratory section of the Polypharmacy: Manage Medicines app9 which supports clinicians and patients when discussing the suitability of a DPI rather than an MDI.

There are links to practical tips and support available from various sources to reduce carbon emissions from pMDIs, e.g. PrescQIPP and Greener practice.[83],[84]

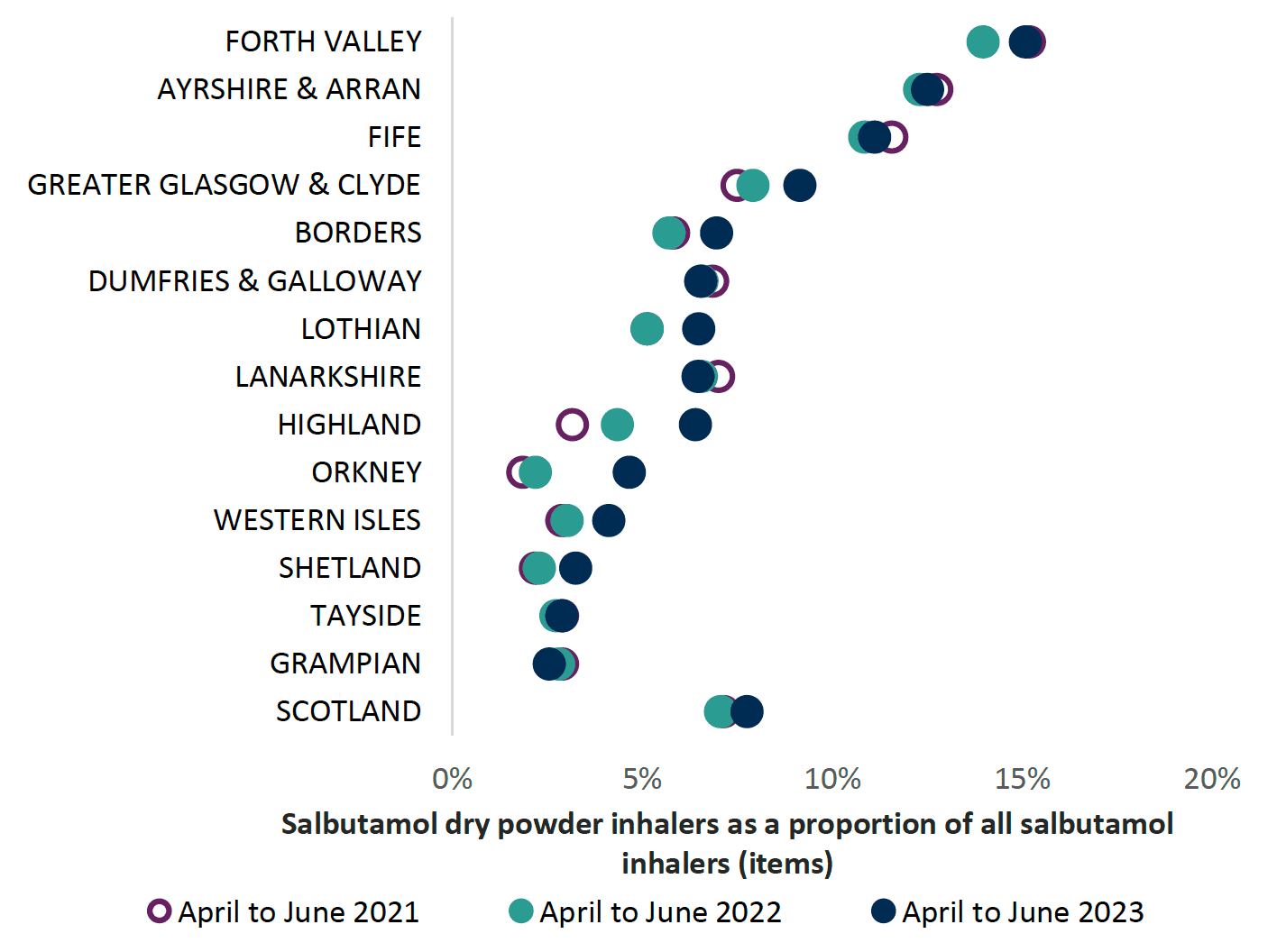

Chart 16 below highlights that the use of DPI for salbutamol is low. In NHS Scotland only 7.8% of salbutamol inhalers are DPIs. If consideration is given to switching a patient to a DPI the clinician should be confident that the patient can use the DPI for acute circumstances. They may not be suitable for the very young or very old (see Appendix 2).

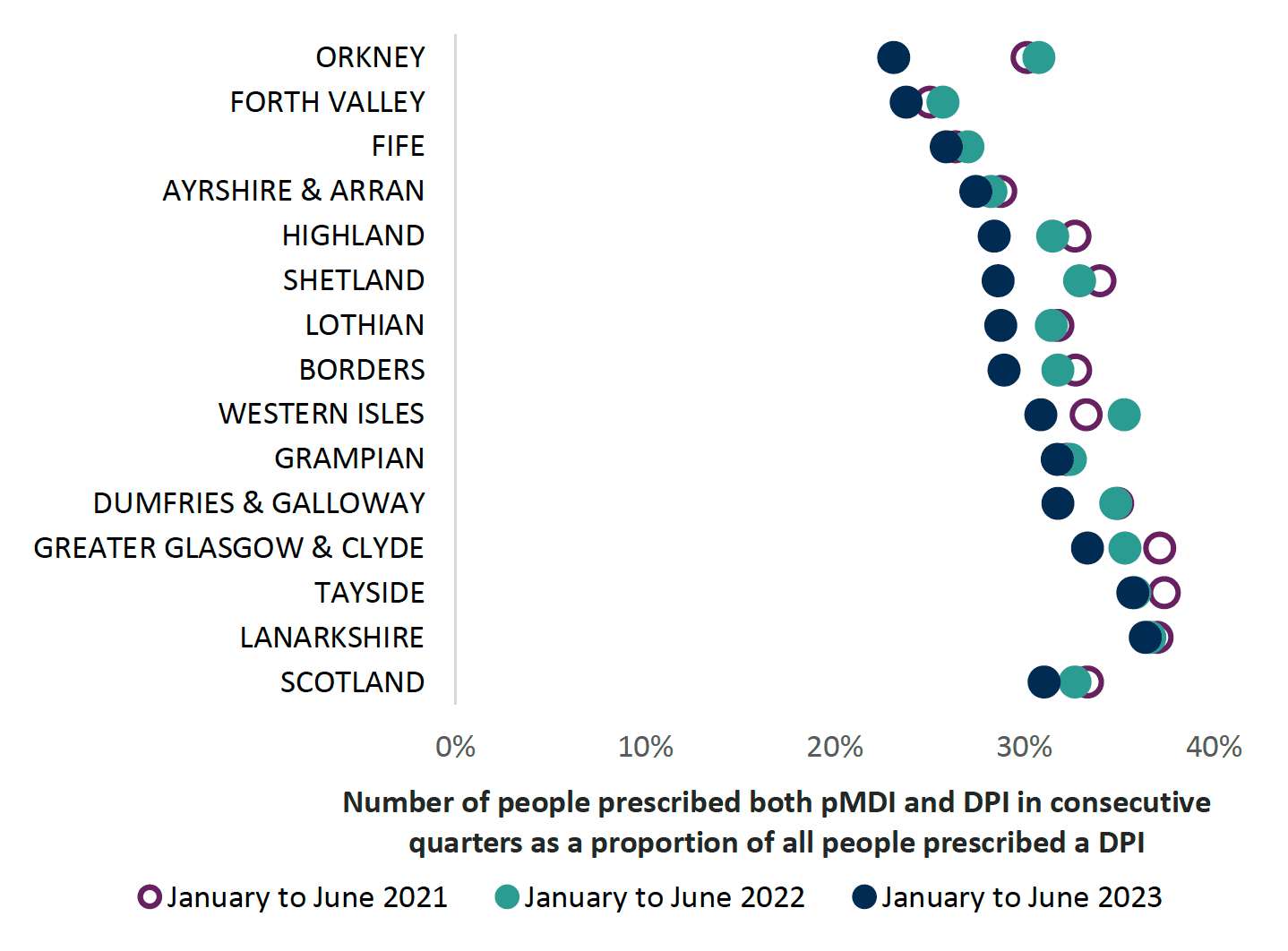

Proportion of patients receiving reliever and preventer inhalers in (BNF Chapter 3) as different devices

Using different devices may cause confusion regarding inhaler technique and lead to increased errors in use.6 If the patient can use both a pMDI and a DPI then carbon emissions will be reduced if the pMDI inhaler is switched to a DPI.

In Chart 17 below, NHS Boards at the top of the chart have a lower proportion of patients on two different devices. Healthcare professionals are advised to include this as part of their respiratory review.

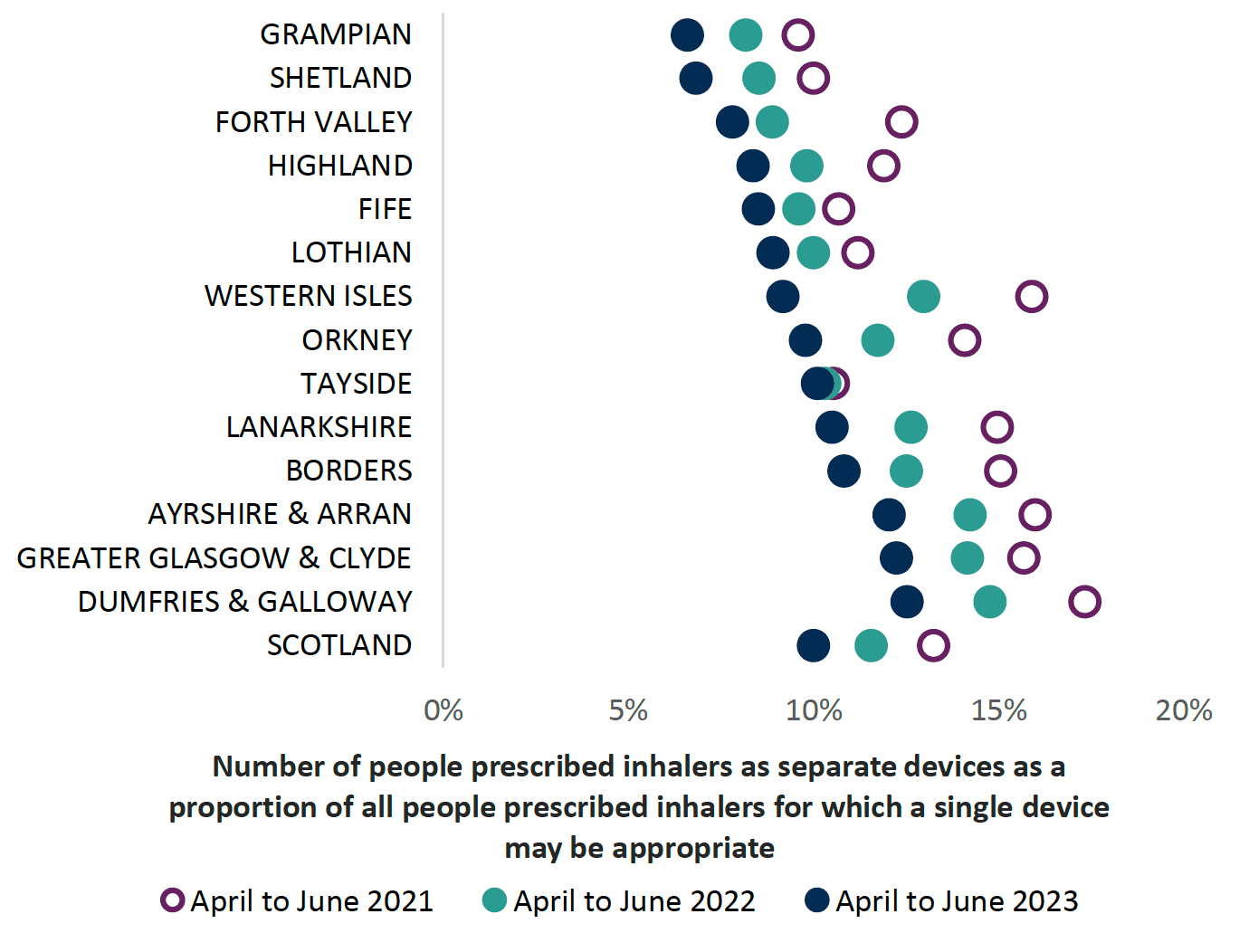

Proportion of patients receiving inhalers which could be prescribed as a combination

Clinicians are recommended to prescribe combination inhalers where appropriate, to improve overall adherence6 and to guarantee that a LABA is not taken without corticosteroid for asthma.6 Incorporating this consideration into a respiratory review will also result in reduced overall carbon emissions, as one inhaler is being used instead of two.

Chart 18 indicates those patients who may be considered for a combination inhaler, and all NHS Boards are improving. Please note that not all combination inhalers are licensed for both asthma and COPD. Please refer to individual Summary of Product Characteristics.

Area wide projects to promote inclusion of environmental focus for local formularies

1. The NHSGGC asthma and COPD Inhaler device guide includes a traffic light system on their formulary

| Environmental Impact | |

|---|---|

| CO2e | low CO2 emissions |

| CO2e | high CO2 emissions |

| CO2e | very high CO2 emissions |

Case Study from NHS Lothian highlighting success in reduction of SABA inhalers

Background

Overreliance of short-acting beta-agonists (SABA) often indicates poor asthma control and is a predictor for future risk of asthma attack and death. The Scottish Therapeutics Utility (STU) tool uses data from GP health records to provide practice-level reports on repeat and high-risk prescribing. STU contains five searches relating to respiratory, including >12 SABA in one year, without a diagnosis of COPD’. STU is installed across Lothian, yet not every practice used it. We aimed to improve primary care prescribing of SABA in NHS Lothian, Scotland, by improving awareness of STU data.

Methods

A training event raised awareness of STU and the ease at which high risk asthmatic patients could be identified. Practices were incentivised to analyse their data and review patients’ over-ordering SABAs. We analysed SABA prescribing data extracted from STU before (June 2019) and after the intervention (May 2021).

Results

Before the intervention, >12 SABA were prescribed to an average of 56 patients per practice (standard deviation (SD) 71). There was wide variation in prescribing: per practice, the minimum number of individuals receiving >12 SABA was 10; the highest was 602 patients. Following the intervention, the number of individuals receiving >12 SABA decreased with an average of 36 per practice and a reduction in variation between practices (SD 28).

Lessons learned

Although STU data was available prior to the intervention, few practices were aware of the benefits. Following the intervention, a reduction in the number of individuals who were prescribed >12 SABA per year which was seen across all areas of the health board.

Messages for others

We saw a reduction in SABA over-prescribing in NHS Lothian by promoting the use of primary care data to help educate and encourage practices to change prescribing. To see change, we needed to raise awareness directly with users.

Contact

Email: EPandT@gov.scot

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback