Respiratory conditions - quality prescribing strategy: improvement guide 2024 to 2027

Respiratory conditions are a major contributor to ill health, disability, and premature death – the most common conditions being asthma and COPD. This quality prescribing guide is designed to ensure people with respiratory conditions are at the centre of their treatment.

5. Asthma

Asthma

Over five million people are receiving asthma treatment in the UK. Asthma accounts for 2-3% of primary care consultations, 60,000 hospital admissions, and 200,000 bed days per year in the UK.[15] The Asthma and Lung UK report identified that poor access to care, outdated treatment guidelines and an ineffective care pathway has left the UK with some of the worst asthma outcomes in Europe.[16]

Summary of recommendations in asthma

In all individuals with asthma

- clinical recommendations are to review patients that are taking three or more reliever inhalers annually. However, the clinical and patient consensus was to prioritise those prescribed six or more reliever inhalers annually. This is a trigger for timely, priority review. An immediate prescription may be necessary, but review should take place before authorisation of the next prescription

- review patients on SABA inhalers alone, clarifying the diagnosis and establishing reasons for SABA only use

- review patients with asthma prescribed SABA and LABA without ICS

- review patients with asthma who have been prescribed an ICS inhaler and do not currently order on their repeat prescription - assess adherence and understanding of treatment to establish appropriate use of SABA inhalers

- review inappropriate use of high strength corticosteroid inhalers (maintaining patients at the lowest possible dose of inhaled corticosteroid)

- reductions in high dose ICS should be considered every three months, decreasing the dose by approximately 25 to 50% each time and arranging regular review as treatment is reduced

- issue a steroid treatment card to patients on inhaled high dose corticosteroids – a steroid emergency card may also be required

- review montelukast at four to eight weeks following initiation to ensure a response and that therapy is still required

In severe asthma

- identify patients at risk of severe asthma and where modifiable risk factors are addressed and asthma control remains suboptimal, refer to secondary care for treatment optimisation

In children with asthma

This guidance is not for children, therefore prescribers should refer to guidance on asthma management in children, however, there are two medication safety points to highlight:

- recommendation for regular growth monitoring when treating children with ICS

- ensure children on medium / high-dose ICS are under the care of a specialist paediatrician

Principles of prescribing for asthma

Asthma is a chronic respiratory condition associated with airways inflammation and hyper-responsiveness.

The aim of treatment is control of the disease with:

- no daytime symptoms

- no night-time waking due to asthma

- no need for rescue medication

- no asthma attacks

- no limitations on activity including exercise

- minimal side effects from medication

- normal lung function (in practical terms FEV1 and/or PEF>80% predicted or best)[6]

Inhaled therapy is used as the main treatment of asthma, which should be started at the level most appropriate to the initial severity of asthma symptoms. The aim is to achieve and maintain early control by increasing treatment as necessary and reducing unnecessary treatment when control is good.6 Personalised asthma action plans, agreed with the healthcare professional, empower individuals to gain control using the minimum dosage of inhaled corticosteroid.[6]

Inhaled corticosteroids are the most effective preventer drug to achieve treatment goals. Add-on therapies, including long-acting beta2 agonists (LABA), leukotriene antagonists, long-acting muscarinic antagonist (LAMA) and theophyllines, should only be initiated after checks to inhaler technique, adherence and elimination of trigger factors. People with asthma should be reviewed at least annually to determine whether their existing treatment regime is adequately managing their symptoms.[6] Clinicians should target care and review to optimise therapy and management, considering frequency of review for those most at risk.

Inhaler device selection is important. People with asthma should receive training on how to use their inhaler device and be able to use the device.[6] The environmental impact of inhalers is a key consideration and prescribers are asked to consider inhalers with a lower global warming potential where appropriate for the individual (see chapter 10).

In frail and older adults

- Lung function generally decreases with longer duration of asthma and increasing age, due to stiffness of the chest wall, reduced respiratory muscle function, loss of elastic recoil and airway wall remodelling.[26]

- Factors such as older age may affect inhaler technique. A review was not able to determine whether this was related to dexterity, cognition, physical ability or the device. [17] Inhaler choices should be made with the patient, ensuring the right device for the right patient.[9]

- Factors such as arthritis, muscle weakness, impaired vision, and inspiratory flow should be considered when choosing inhaler devices for older adults.[26] Individuals with cognitive impairment may require carers to help them use their asthma medications effectively.

To prescribe most effectively for people with asthma, we recommend the ‘what matters to you?’ principles and the Polypharmacy 7-Steps approach. Table 1 outlines the main principle for treating patients with asthma.

Table 1: Principles of treating patients with asthma

Polypharmacy review 7-Steps

1 What matters to the patient?

- Ask the patient what matters to them? Ask patient to complete Patient Reported Outcomes Measures (PROMs) (questions to prepare for my review) before the review

- How does the condition affect patient’s day to day life/activities?

- Take account of comorbidities when prescribing for asthma, by using the Polypharmacy 7-Steps approach

- Ensure patient has a personalised asthma action plan

- Do environmental prescribing issues matter? (see chapter 10)

2 Identify essential drug therapy

- Asthma diagnosis confirmed?

- Fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) test could be used as an optional investigation to test for eosinophilic inflammation when there is diagnostic uncertainty.[6] In the absence of FeNO, assessing eosinophil levels as part of a full blood count (FBC) may assist with review. FBC would give access to eosinophil results as part of an asthma assessment[26]

- Ensure asthma therapy is optimised as per local / SIGN / BTS guidelines[6]

- Consider the use of Maintenance and Reliever therapy (MART) regimen in patients where there is poor control or adherence when on separate medium dose ICS/LABA and SABA[6]

- Consider use of an anti-inflammatory reliever (AIR) inhaler, that is a low-dose ICS-formoterol, as this approach reduces risk of severe exacerbations compared with using a SABA reliever[26]

- Assess adherence, review inhaler technique and eliminate trigger factors prior to initiating or adjusting therapy using an asthma action plan

- Confirm ongoing need for and effectiveness of medication and screen for side effects

3 Does the patient take unnecessary drug therapy?

- Discuss SABA use with patients prescribed more than three SABAs annually as this is a marker of poor control

- When asthma is controlled and stable, clinicians should consider stepping down inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) treatment slowly, every three months reducing by 25 to 50% each time and monitoring for deterioration6 as part of a holistic asthma review

4 Are therapeutic objectives being achieved?

- Can the patient use their inhalers properly? Assess asthma control using a validated questionnaire such as the Asthma Control Test (ACT) or Asthma Control Questionnaire (ACQ).[21] Consider addition of spacer to aid MDI lung deposition or consider DPI/SMI if appropriate

- Any patient who has asthma medicine started or changed should be reviewed within three months

- Medication should be titrated to a dose which balances maximum clinical efficacy with minimal risk and stopped if found to be ineffective or if adverse effects outweigh benefits

- If asthma is not adequately controlled on recommended initial or additional therapies, as per BTS/ SIGN,[6] patient should be referred for specialist assessment

- Exacerbations should be considered as an opportunity to review therapy, optimise treatment and ensure self-management plans are updated.

- Consider risk factors for future risk of asthma attack and address these when prescribing - for instance, patients:

- with an asthma attack in the past

- who have received more than one course of oral corticosteroids in one year

- who have received more than six SABA inhalers a year should be prioritised for an asthma review

- on high dose inhaled steroids

- with multiple morbidities e.g. COPD, depression, Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease

- with poor asthma control

- who smoke

- Review those who have received emergency hospital treatment for an asthma attack within two working days[6]

- Once the dose is stable and effectiveness has been established, ongoing review should occur as clinically appropriate, with follow up at least annually if asthma control has been achieved

- Delivery of a SABA via a pMDI and spacer or a DPI leads to a similar improvement in lung function as delivery via a nebulizer for treatment of acute exacerbations. A person-centred approach to treatment plans for acute exacerbations should be taken and that individuals have a reliever inhaler that they can use26

- Consider switch to pMDI with lower global-warming potential where this is clinically appropriate

- Ensure awareness of how allergies (pet, pollen, dust), air pollution can affect respiratory conditions

- Vaccinations should be offered if not up to date as per national guidance

- Individuals should be encouraged to engage in appropriate physical activity - social prescribing such as exercise would be dependent on ability

- A breathing exercise program can reduce symptoms

- Smoking cessation should be advised and the adverse effects of smoking on children highlighted. Offer appropriate support - signpost patients to the NHS inform Quit Your Way Scotland website (includes community pharmacy services)

- Weight reduction should be considered in patients who are overweight (BMI 25 – 29.9) or obese (BMI >30) to reduce respiratory symptoms[6]

5 Is the patient at risk of Adverse Drug Reactions (ADR)s or suffer actual ADRs?

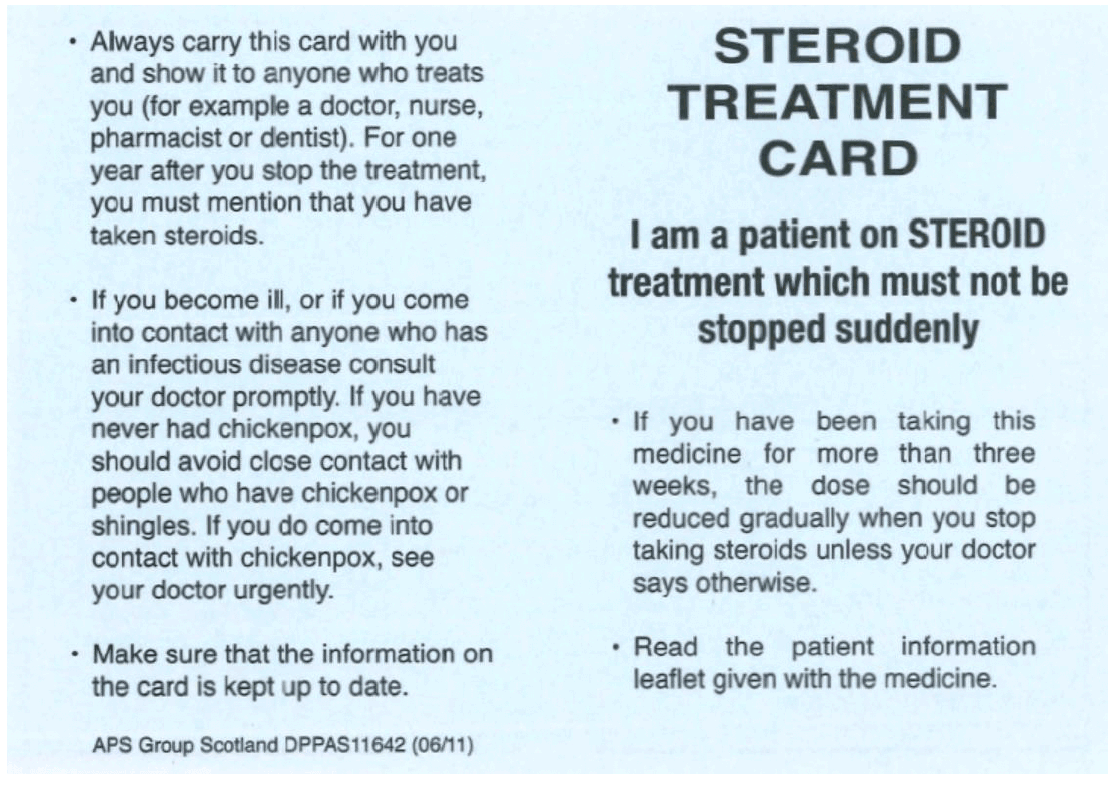

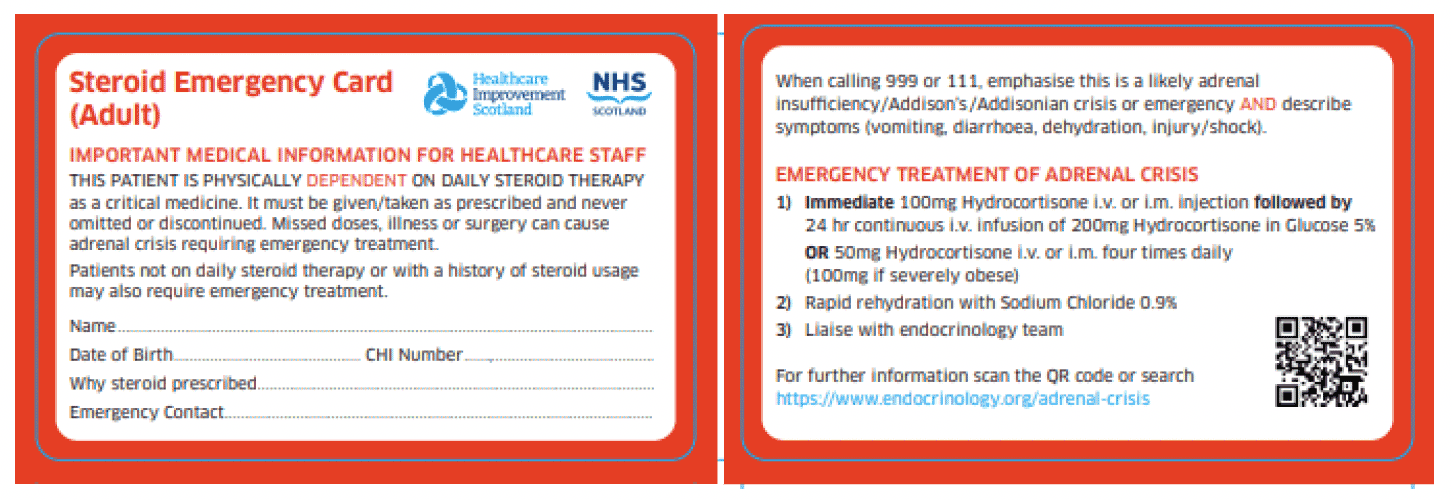

- Steroid treatment cards should be provided to patients on high dose steroids (both oral and inhaled). A steroid emergency card may also be required. [18]

- Review risk of osteoporosis if on long term or frequent (more than three or four courses a year) oral corticosteroid treatment [19]

- Take measures to reduce the risk of and increase awareness of oral thrush - ensure correct technique to reduce incidence - a spacer device is recommended for use with a pMDI and will reduce oral thrush side effects

- Yellow card reporting of ADRs

6 Sustainability

- Opportunities for sustainable prescribing and cost minimisation should be explored but only considered if effectiveness, safety or adherence would not be comprised

- For new drugs, ensure prescribing is in line with Health Board formulary recommendations

- For environmental considerations, using a patient centred approach, consider switch to low GWP inhalers for patients with asthma who have an adequate inspiratory flow

7 Is the patient willing and able to take drug therapy as intended?

- A personalised asthma action plan is key to this approach, with focus on inhaler technique, peak flow monitoring, worsening symptom advice, appropriate use of a spacer and avoidance of new trigger factors

- Make patient aware of support information e.g. the My Lungs My Life website ( Appendix 1)

- Non-attenders should be followed up – alternative strategies to encourage engagement may be required (e.g. through community pharmacy / Near Me / telehealth acknowledging limitations)

- Agree with the patient arrangements for repeat prescribing - signpost to Medicines Care and Review service in Community Pharmacy where appropriate

- ask patient to complete the post-review PROMs questions after their review

Prescribing issues to address

The issues identified below are priority areas of prescribing, where there is unwarranted variation within Health Boards and where accurate prescribing data can be provided. Ensuring asthma medicines are reviewed and optimised regularly will reduce this unwarranted variation. The indicators below help to highlight some higher risk groups who may benefit from prioritisation of review, focusing on patient safety and quality prescribing. Consideration should be given to prioritisation of these groups to optimise care. The indicators focus on ensuring quality prescribing and any of the recommendations made follow national clinical guidance.[6] The indicators included are as follows:

- prescribing of short-acting beta-agonists (SABA) per annum

- prescribing of inhaled high dose corticosteroids

- prescribing of long-acting beta-agonists (LABA) without inhaled corticosteroids (ICS)

- prescribing of SABA only

- prescribing of leukotriene receptor antagonists

Prescribing of short-acting beta-agonists (SABA)

Evidence for review of SABA

Overreliance on SABA is an indicator of poor asthma control.[20],[26] It is essential that patients who appear to be overusing SABA inhalers are assessed for control of symptoms as part of a holistic asthma review. Asthma control test (ACT) questions[21] highlight that a patient is not controlled if they use a SABA inhaler three or more times in a week.[6] The National Review of Asthma Deaths (NRAD) report[22] found that patients who used more than 12 reliever inhalers per year were at a greater risk of uncontrolled asthma and sudden death. There was evidence of under-prescribing of preventer medication. Use of 12 SABAs in one year implies the use of 46 puffs in one week and for six SABAs a year is 23 puffs a week.[23] In the SABINA study,[24] an association across all asthma severities was found between high SABA use, of more than three inhalers per year, and an increase in exacerbation rates and healthcare utilisation.[25] It is crucial that patients understand the importance of when and how to use their inhalers and of adherence to therapy with their preventer inhaler.[22]

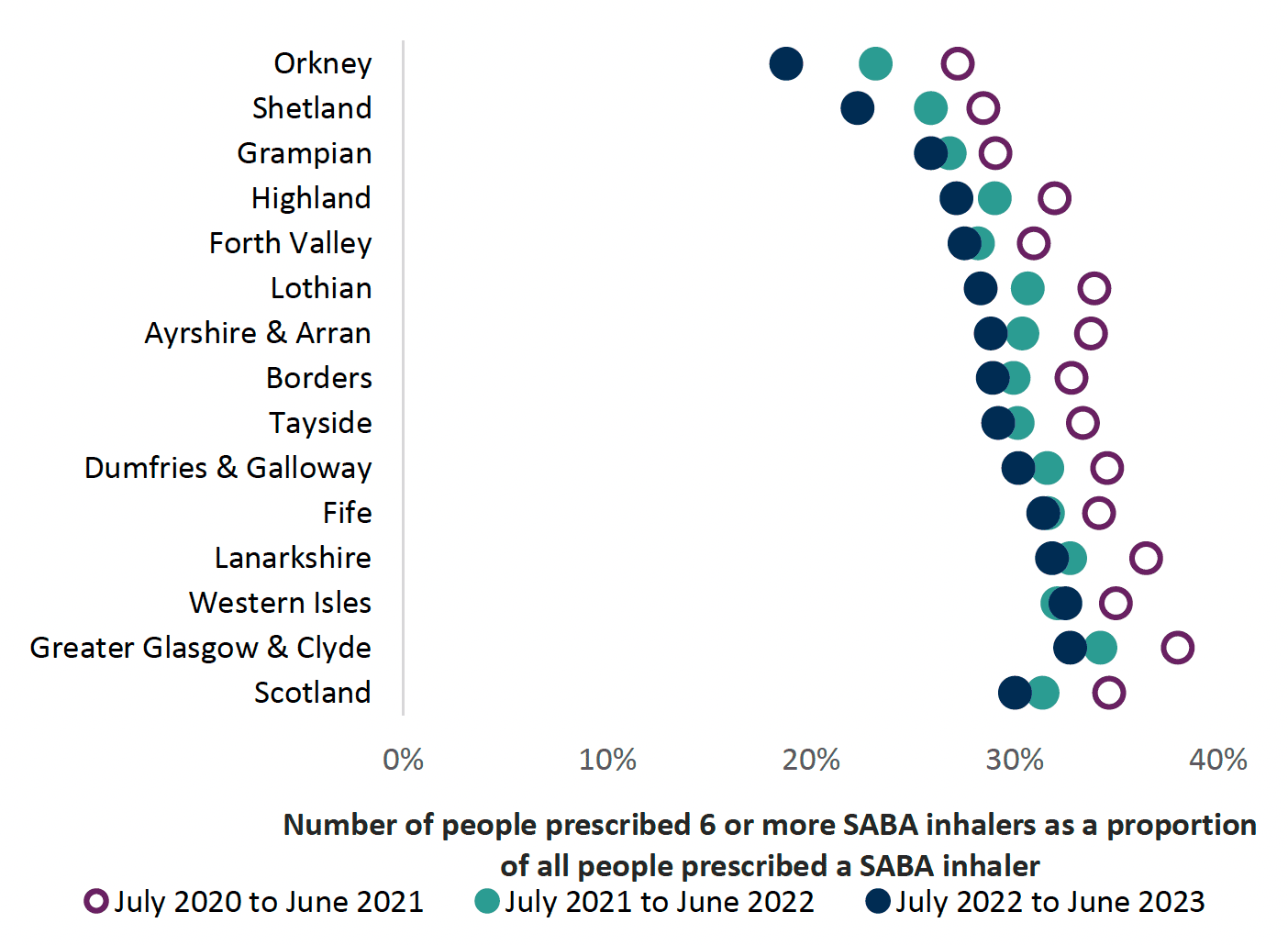

The main focus of an asthma review is to ensure that the individual’s condition is well controlled, they are prescribed the optimum inhaler therapy in alignment with current guidance and are using their inhalers effectively. We know that there are many people with asthma in Scotland who are prescribed six or more SABA inhalers in 12 months (see Chart 1 below). Use of three or more SABA inhalers is associated with a higher rate of exacerbations and hospitalisation.[24]

Following clinical consensus regarding asthma control, this indicator has been reduced from the previous 12 SABA inhalers prescribed annually to recommend that a patient prescribed six or more inhalers annually is a trigger for timely, priority review (see Chart 1). This should ideally take place before the issue of the next prescription. Review is required for those using three or more SABA inhalers, but prioritisation may be considered for those using six or more SABA inhalers.[25]

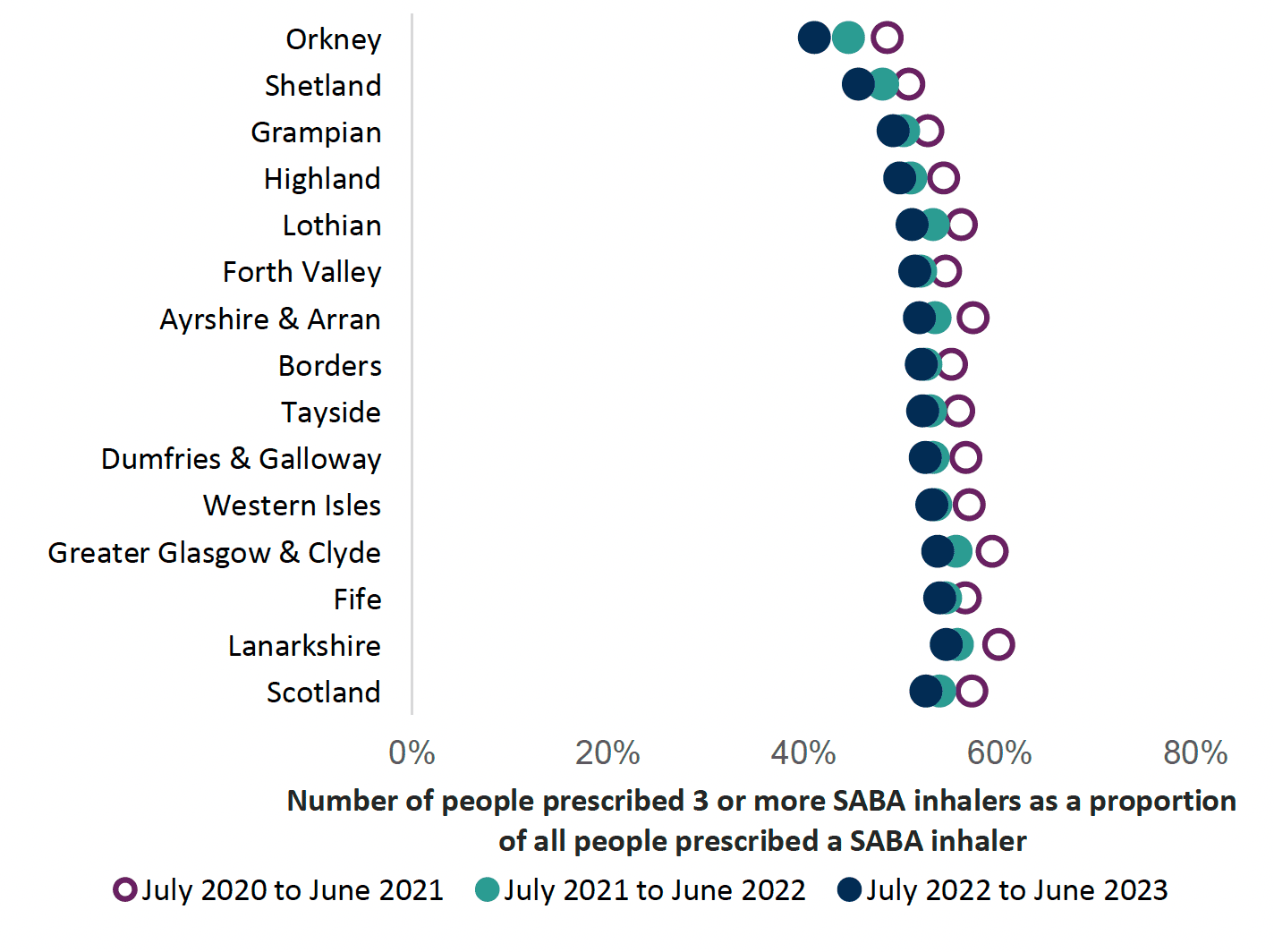

This guide includes an indicator chart of people prescribed three or more SABA inhalers as an aspirational level, as a person with well-controlled asthma would need no more than this (see Chart 2). This should be discussed at their annual routine review. This indicator is a guide and is unable to distinguish between people with asthma and COPD.

SABAs are not first step maintenance treatment for asthma, a low dose ICS is recommended.6 The Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) guidelines recommend initiation of ICS-containing treatment when, or as soon as possible after a diagnosis of asthma is made.[26] They recommend reliever therapy using an anti-inflammatory reliever (AIR), a low-dose combination ICS-formoterol inhaler taken as needed as preferred step one treatment.[26] As-needed low-dose ICS-formoterol reduces the risk of severe exacerbations and emergency department visits or hospitalisations by 65% compared with SABA-only treatment.[27] Licensed indications for products and local formularies should be checked for choice of low-dose ICS-formoterol combinations, where appropriate, if prescribing the AIR regimen.

It should be noted that emergency supplies of SABA inhalers are possible to obtain from the community pharmacy. Liaison with community pharmacy colleagues is advised to help reach those people with asthma who may be poorly controlled and do not attend asthma reviews.

The Scottish Therapeutic Utility (STU) software (chapter 12) is recommended, to support GP Practices to identify individuals with asthma who are over-reliant on SABA inhalers using practice coding.

Charts 1 and 2 highlight that the number of SABA inhalers that patients have received annually has remained fairly constant, after a slight increase during July 2020 to June 2021 across NHS Scotland. This may be due to prescribing of SABA inhalers in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Prescribing of inhalers with dose counters may assist in monitoring adherence with inhalers and ensure individuals know how many doses remain in the inhalers to prevent medicine waste.[28]

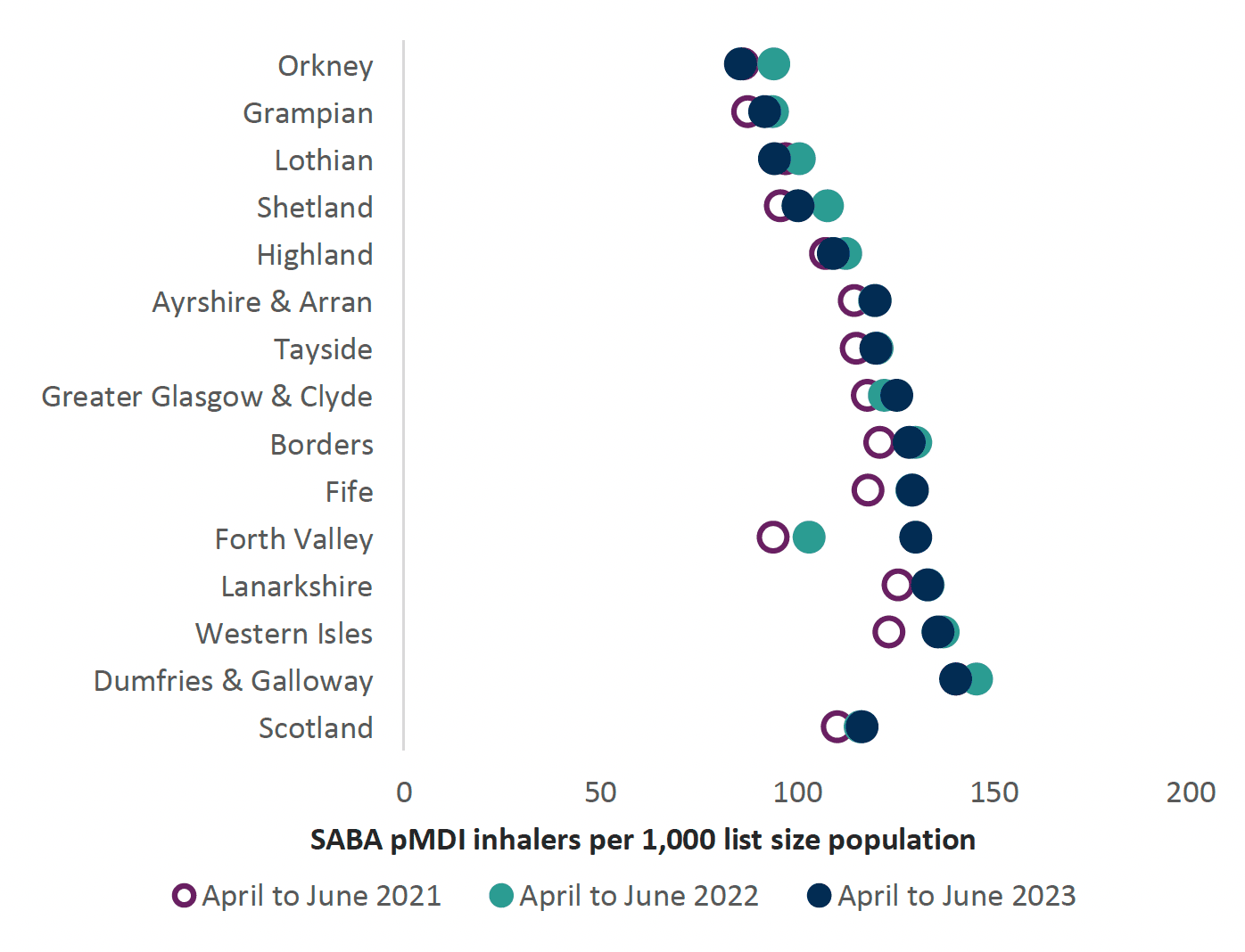

Review of high SABA pMDI use

A recent study found that SABA inhalers accounted for the majority of pMDIs prescribed and advocated better disease control to reduce SABA inhaler use and CO2 emissions[29] (see environmental chapter). Approximately 70% of all inhalers in NHS Scotland are prescribed as an pMDI. The UK has a high proportion of pMDI use (70%) compared with the rest of Europe (< 50%) and Scandinavia (10–30%). Figures from Scandinavia show a lower rate of deaths.[30]

Reviewing patients regularly, optimising treatments and providing education on good control of respiratory disease will reduce SABA inhaler use, improve patient care and disease control. This will also support reduction in CO2 emissions, which is a target for NHS Scotland (see environmental chapter). Chart 3 below highlights the proportion of SABA pMDI inhalers prescribed in each NHS Board.

Prescribing of high dose corticosteroid inhalers

There are safety concerns regarding the inappropriate use of high dose corticosteroid inhalers and the importance of ensuring that the patient’s steroid load is kept to the minimum level whilst effectively treating symptoms. It is recognised that some patients will require treatment with high-dose ICS. This indicator acts as a guide for highlighting use of inhaled high dose corticosteroids but is unable to distinguish between patients with asthma and COPD. The STU software will allow GP practices to identify patients within each cohort for review.

Patients on inhaled high dose corticosteroids (or multiple steroid preparations) should be issued with a steroid treatment card (blue), see Figure 4. There is an additional steroid emergency card (Figure 5) which alerts patients who are dependent on long term steroids and at risk of adrenal insufficiency to the potentially serious, systemic side effects from them. A full list of steroid doses to assist with determining who should be issued with a steroid emergency card (red) is contained within the Healthcare Improvement Scotland advice[18] and STU software will assist identification of these patients. The most concerning side effect is adrenal suppression, others include growth failure; reduced bone density; cataracts and glaucoma; anxiety and depression; and diabetes mellitus.[31]

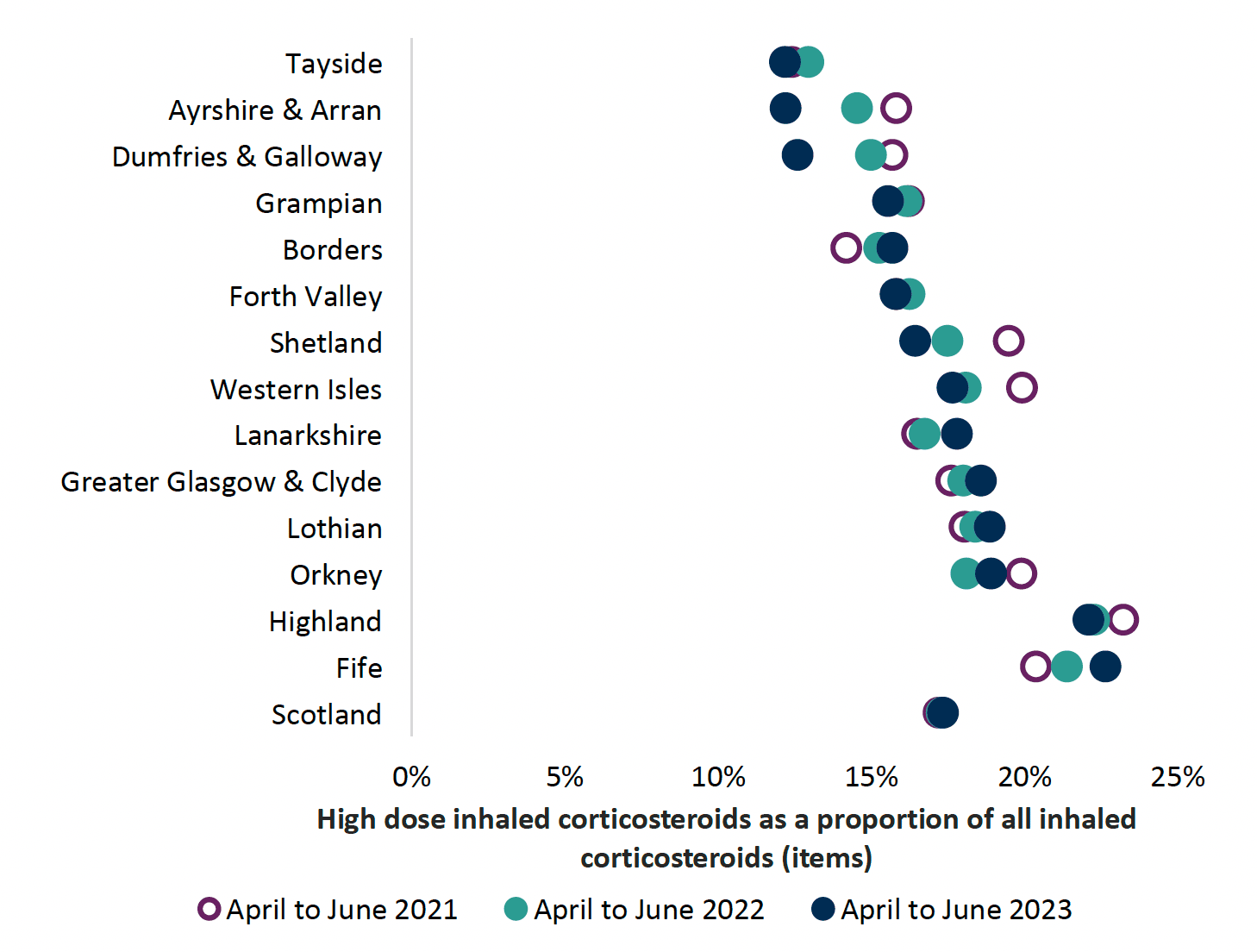

Chart 4 shows that high dose corticosteroid inhaler prescribing has increased in most NHS boards since 2021.

This guidance is not for children; therefore prescribers should refer to guidance on asthma management in children, however, there are two medication safety points to highlight. Prescribing of high dose inhaled corticosteroids in children, aged under 12 years, is of particular concern due to long term safety concerns. Children on high dose corticosteroids should be reviewed and under the care of paediatricians with a special interest in respiratory medicine. Transition from child to adult services should be considered for children with unstable asthma or co-existing risks, such as food allergies and a review carried out in children’s services to facilitate this. There is a report available using the STU utility to identify high dose corticosteroid use in children under 12 years.

When treating children with ICS:[6]

- it is important to record growth (Height and weight centile) on an annual basis using the same equipment6 (unreliable indicator of adrenal suppression) - if there are concerns regarding growth, advice should be sought from a paediatrician

- high-dose ICS should be used only under the care of a specialist paediatrician

- adrenal insufficiency should be considered in any child with shock and/or reduced consciousness who is maintained on ICS

Evidence for review of high dose inhaled corticosteroids

SIGN 158 recommends the following for adults and children.[6]

Patients should be maintained at the lowest possible dose of inhaled corticosteroid. Reduction in inhaled corticosteroid dose should be slow as patients deteriorate at different rates. Reductions should be considered every three months, decreasing the dose by approximately 25 to 50% each time. It is difficult to set a specific threshold level of ICS inhalers for review due to their varying potencies, dosing and quantities (for example 200 actuations in most ICS MDIs and 100 doses in some ICS DPIs).

It is important to arrange for a regular review of patients as treatment is reduced. When deciding the rate of reduction, it is important to take into account the following aspects: the severity of asthma, the side effects of the treatment, time on current dose, the beneficial effect achieved, and patient preference.

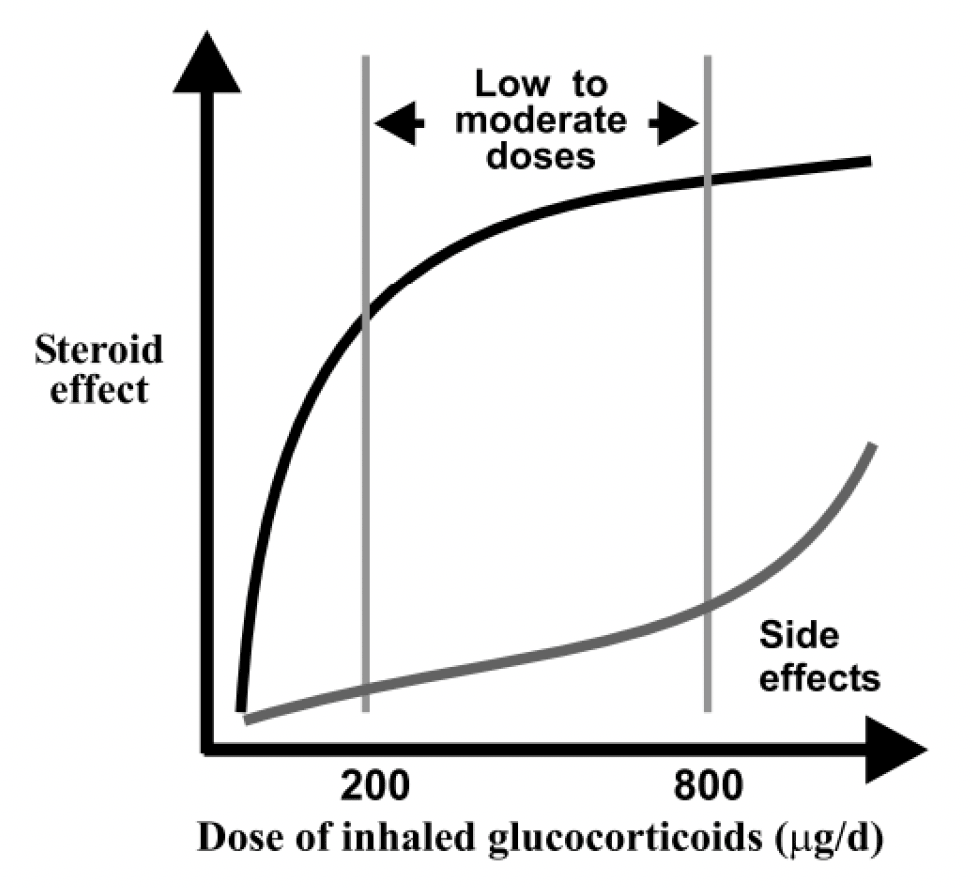

The dose – response curve for inhaled corticosteroids (Figure 6)[32] shows the difference in clinical effect and side effects when a corticosteroid dose is increased. At doses of 800 micrograms per day and above, the clinical benefit of increasing inhaled corticosteroid dose is outweighed by increase in side effects.

Reproduced with permission from National Library of Medicine (Hannu Kankaanranta, Aarne Lahdensuo, Eeva Moilanen, and Peter J Barnes)[32]

Number of inhaled corticosteroids prescribed per annum

People who have been prescribed an ICS inhaler and do not order on repeat prescription should be checked for adherence and understanding of preventer treatment and to establish appropriate use of SABA inhalers. The National Review of Asthma Deaths (NRAD) report[22] highlighted that some people at risk of uncontrolled asthma / sudden death had under used preventer medicines. Most ICS inhalers (pMDIs and DPIs) have a dose counter and that may be used to aid understanding of adherence based on an individual’s asthma management plan.

Conversely, some people may over-order inhalers for various reasons, such as poor understanding of therapy. A review would be advised to explore this. Use of the STU software is recommended for GP practices to identify patients receiving 14 or more ICS inhalers a year (see chapter 12).

Prescribing of SABA plus LABA without ICS

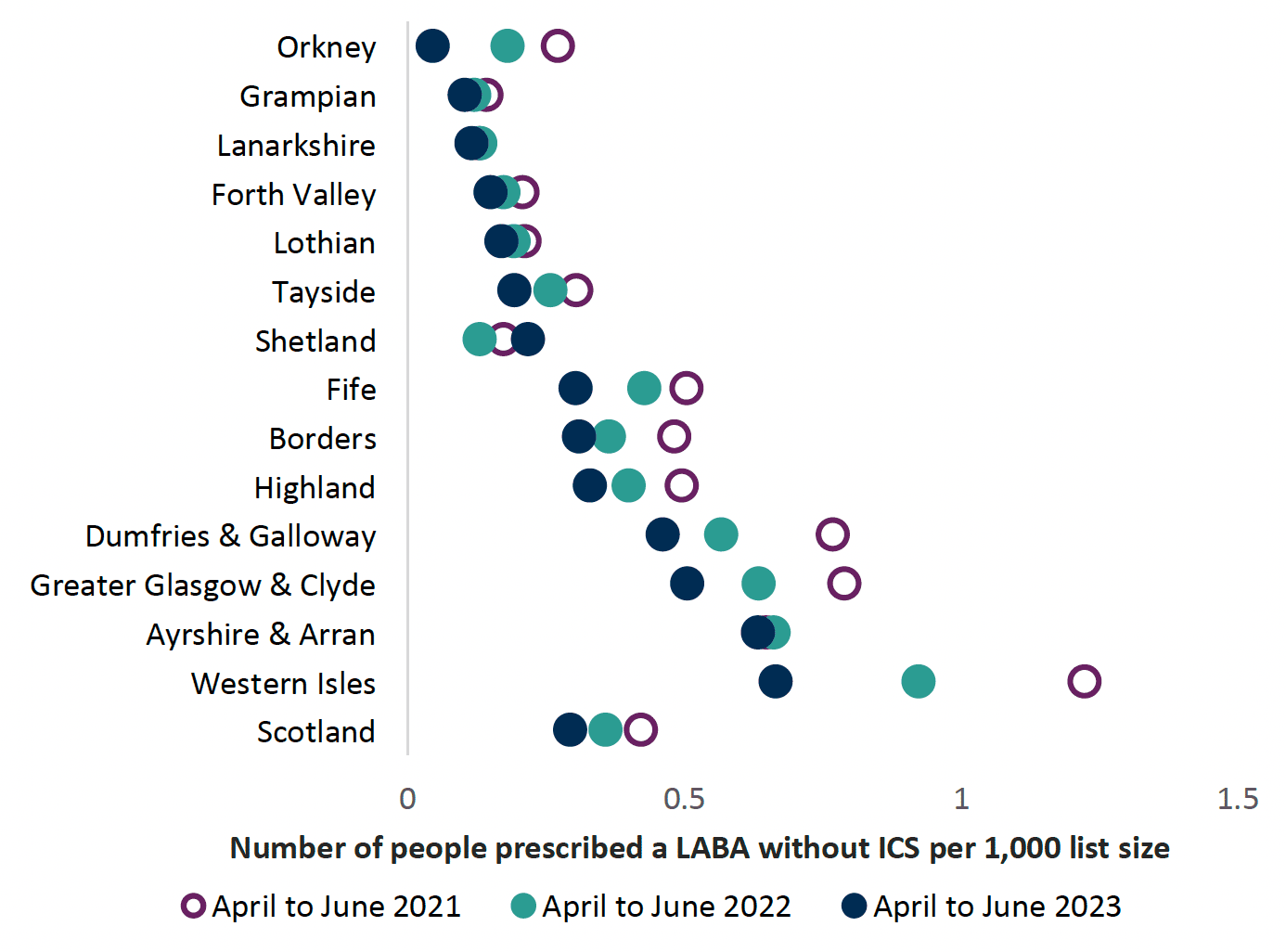

The NRAD report[22] highlighted that individuals with asthma who were prescribed a LABA without an ICS were at higher risk of death. As is clear from Chart 5 the number of people without an ICS prescribed is small and continues to reduce. Some of these patients may have a COPD diagnosis in which case prescribing of a LABA without an ICS would be reasonable.

Prescribing of SABA only

This indicator highlights the proportion of patients who receive a SABA inhaler in the absence of other inhalers. SIGN 158 states that on diagnosis of asthma, patients be considered for monitored initiation on low dose ICS plus a SABA as required and GINA recommends AIR therapy.[26] Patients on SABA inhalers alone should be reviewed, establishing reasons for SABA only use, such as COPD diagnosis, viral wheeze and COVID-19 symptoms.

Using STU software is recommended within GP practices and will allow identification of individuals coded on a SABA inhaler only (see chapter 12).

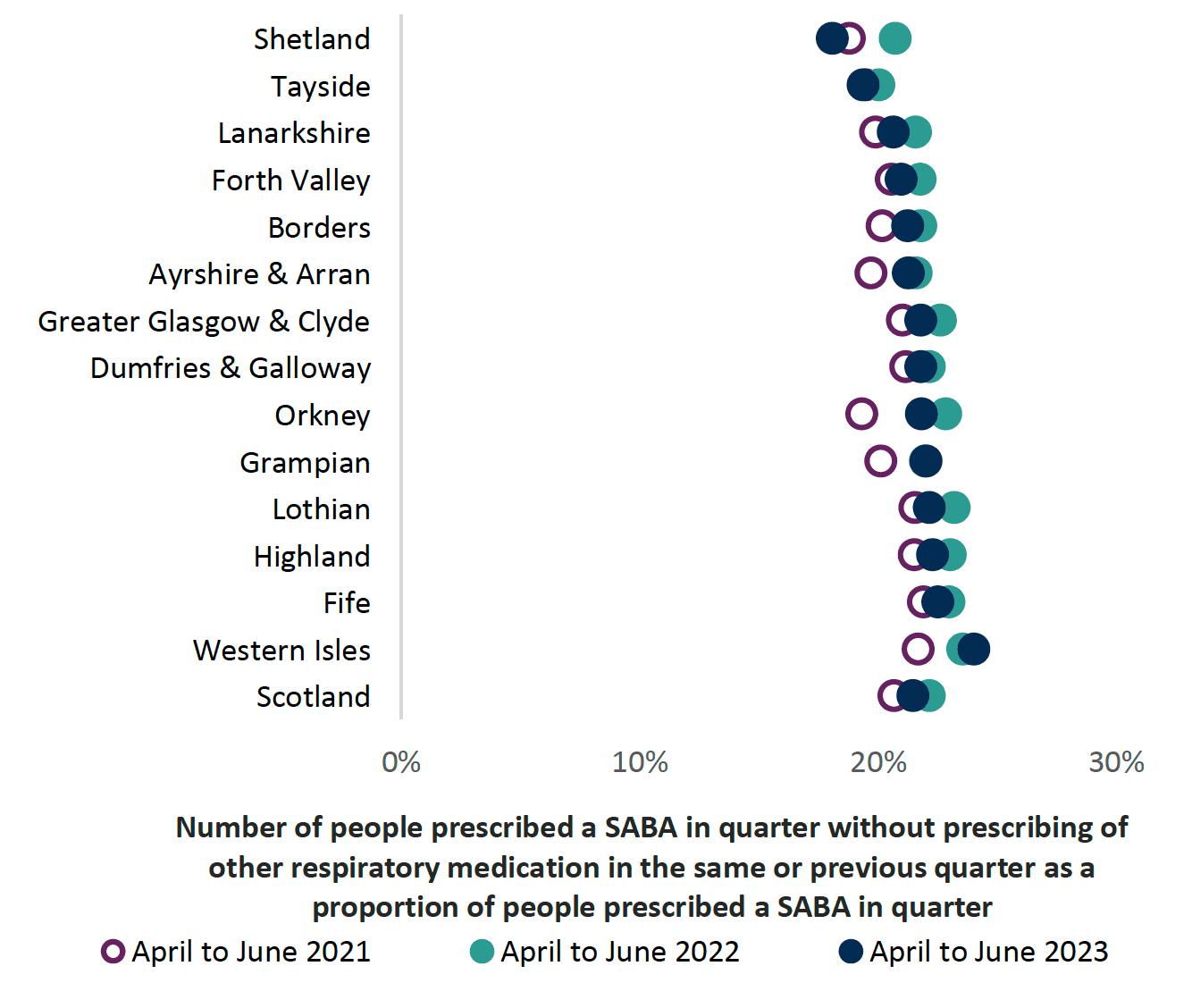

Chart 6 shows that in NHS Scotland approximately 22% of people being prescribed a SABA inhaler are not prescribed other inhaler therapy. As per national asthma and COPD guidelines, very limited numbers of patients should be prescribed SABA inhalers only.

Prescribing of Montelukast (leukotriene receptor antagonist)

Montelukast can be used as an additional add on therapy for asthma in adults. If control remains suboptimal after the addition of an inhaled LABA to low-dose ICS then either:

- increase the dose of inhaled corticosteroids to medium dose

or

- consider adding a leukotriene receptor antagonist6

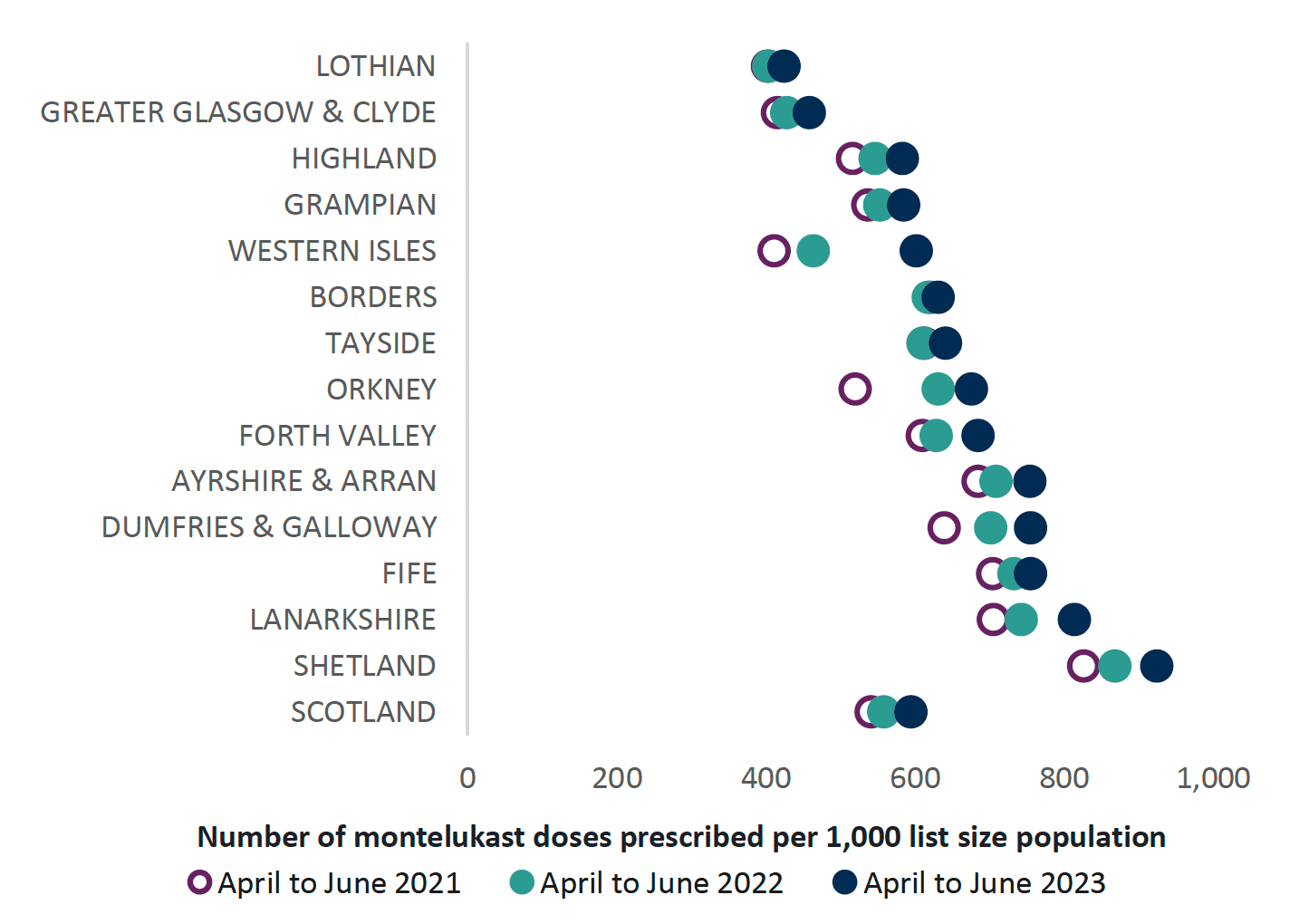

Chart 7 below highlights prescribing of montelukast, which shows a variance in NHS Boards across Scotland. Overall prescribing appears to have increased. Montelukast should be reviewed four to eigh t weeks following initiation[33] to ensure that there has been a response to therapy and that it is still required.

The Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory agency (MHRA) issued a reminder regarding the known risks of neuropsychiatric reactions with montelukast.[34]

A recent EU Review[35] of montelukast confirmed the known risks and that the magnitude was unchanged. The review highlighted that there had been some delays in recognising that neuropsychiatric reactions were a potential side effect to montelukast. Consider the benefits and risks of continued prescribing should these side effects occur.

Treatment of exacerbations

A personalised asthma action plan should identify what to do in the event of worsening symptoms and how to prevent deterioration using the individual’s own inhaler devices, highlighting when emergency care is required. Patients should be encouraged to continue to use their usual inhaler device in an acute exacerbation as this is the device that they will have been taught to use effectively and will be confident in using.

During acute exacerbations, treatment is with repeated administration of SABA, early introduction of oral corticosteroids, and controlled flow oxygen where indicated.

Inhaled SABA therapy such as salbutamol should be administered frequently for patients presenting with acute asthma. Delivery of SABAs via a pMDI and spacer or a DPI leads to a similar improvement in lung function as delivery via a nebulizer for treatment of acute exacerbations.[26]A person-centred approach to treatment plans for acute exacerbations should be taken to ensure that the individual has a reliever inhaler that they can use effectively in the event of an acute attack.[36] If a patient has concerns regarding their ability to use their usual inhaler device during an exacerbation, this should be discussed and a person-centred choice made.

Refer to local acute protocols for management of acute asthma exacerbations in a secondary care setting, including use of agents such as intravenous (IV) magnesium sulfate and aminophylline etc.

Severe Asthma

Severe asthma is defined as asthma that is uncontrolled despite adherence with optimised ICS-LABA therapy and treatment of contributory factors, or that worsens when high-dose treatment is decreased.[26]

Difficult-to-treat asthma is defined as asthma that remains uncontrolled despite prescribing medium or high dose ICS-LABA treatment or requires high dose ICS-LABA treatments to maintain good symptom control and reduce exacerbations.

Poorly controlled and/or unrecognised severe asthma is a significant problem, leading to morbidity and mortality. Severe asthma is associated with poor asthma control, impaired lung function and repeat exposure to oral corticosteroids (OCS) which can lead to further OCS-related adverse effects such as diabetes, adrenal insufficiency, and osteoporosis.

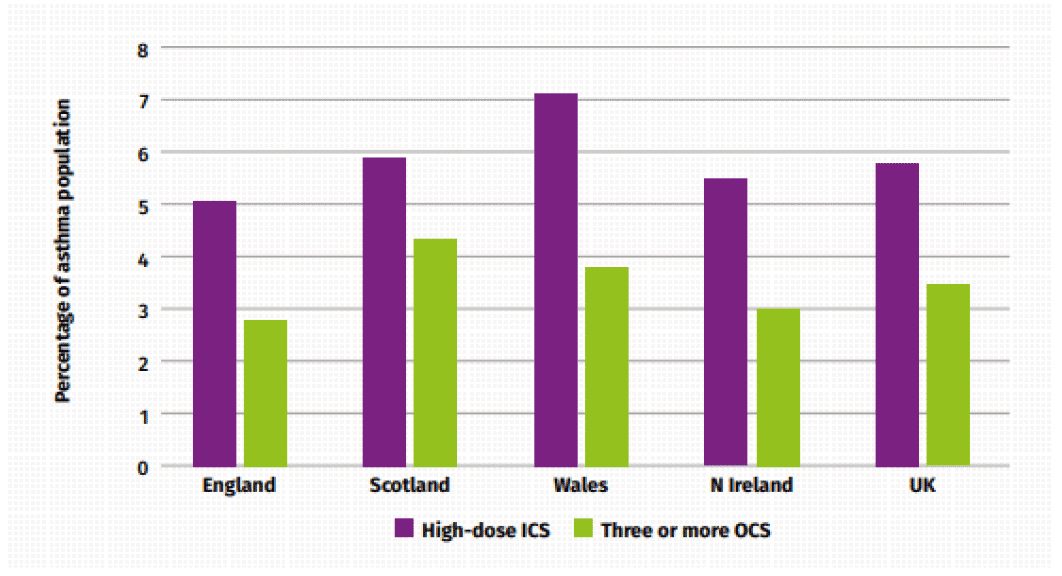

Severe asthma is estimated to affect 3% to 5% of the asthma population. Scotland has higher rates of difficult and severe asthma compared to the rest of the UK.[37]

Proxy measures of inhaled high dose corticosteroids (ICS) or number of courses of oral corticosteroids (OCS) treatments have been suggested as indicators of those at risk of severe asthma.[37] Figure 7 below outlines the differences in difficult or severe asthma prevalence, based on the indicators of high-dose ICS or those receiving three or more OCS courses across the nations in the UK in 2016.[37] For three or more OCS prescriptions Scotland has the highest figure in the UK, with 4.3%, compared to the UK figure of 3.4% of the asthma population.

Early identification of at-risk patients with asthma is key to ensure prompt referral to specialists for consideration of Monoclonal antibody (mAb) therapy where appropriate. Pathways have been developed to support the identification and management of patients at risk of severe asthma.[38]

Criteria to identify patients at risk of severe asthma:

- ≥6 SABA prescriptions in previous 12 months or

- ≥2 asthma exacerbations / OCS prescriptions in previous 12 months or

- ACQ6 >1.5 (or ACT <20) despite maximum inhaled therapies (ICS and LABA and LAMA)[26],[37]

Modifiable risk factors such as smoking status, inhaler technique, adherence and housing conditions should be addressed and a referral made where asthma control remains suboptimal.[38] The Scottish Therapeutic Utility (STU) software will aid identification of these patients within GP practices.

Monoclonal antibodies (mAb) are a type of biologic drug that can be used to treat severe asthma. They target specific biological processes to reduce inflammation in the lungs and currently either target ‘allergic’ asthma or ‘eosinophilic’ asthma. There are various mAbs approved by the Scottish Medicine Consortium (SMC) for Scotland including; benralizumab, dupilumab, mepolizumab, omalizumab and tezepelumab. These medications have been shown to significantly reduce asthma exacerbations, hospital admissions and oral corticosteroid use.[39],[40],[41],[42] The SMC has set strict eligibility criteria for patients receiving these drugs to ensure that they are used for patients most likely to benefit and in the most cost-effective way. Consequently, mAbs are included in SIGN/BTS and NICE clinical guidance for the treatment of severe asthma.[6],[7]

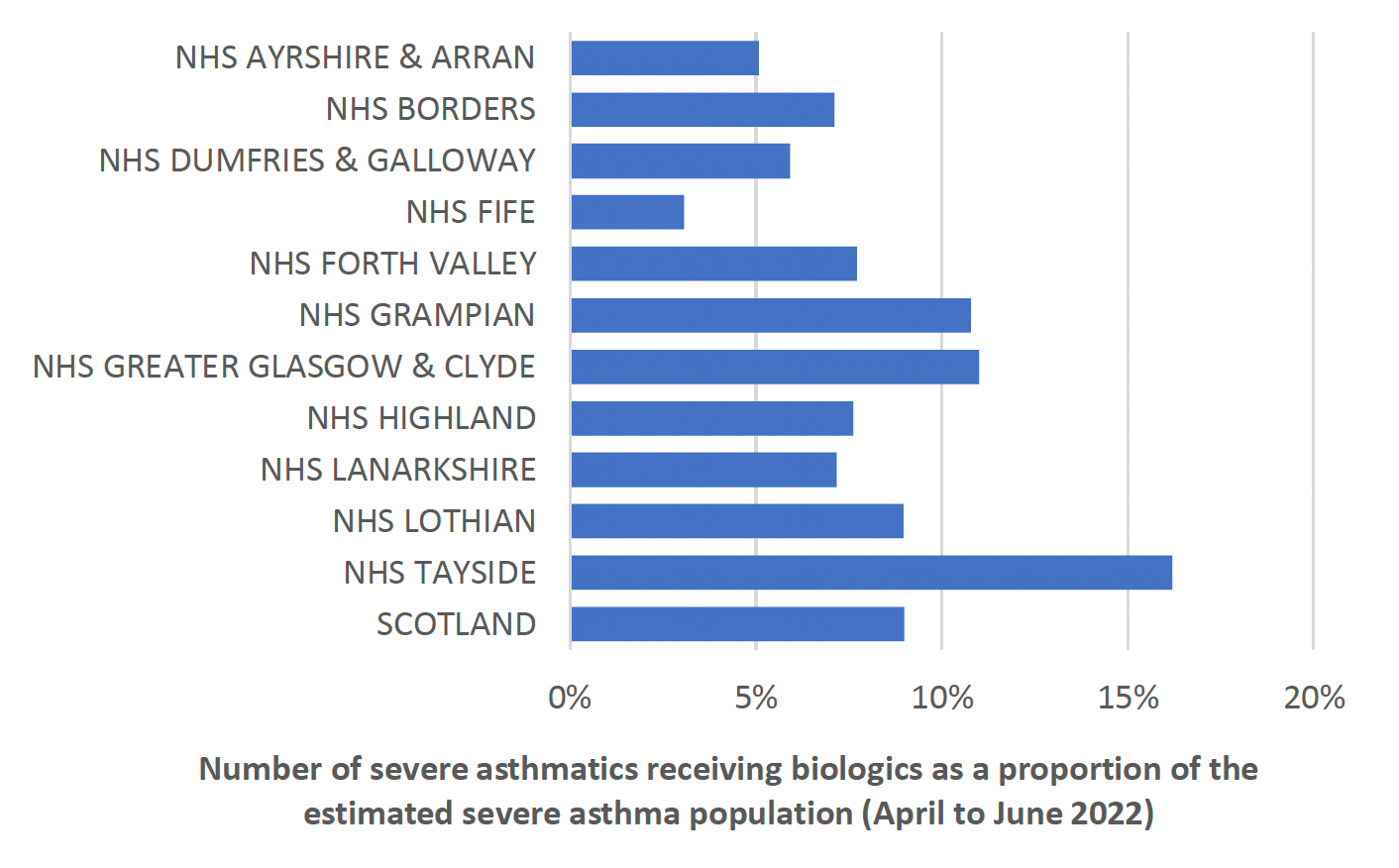

It has been previously estimated that 20% of eligible patients with severe asthma, received treatment with mABs in the UK.[37] The Accelerated Access Collaborative estimated this as 17-21% of eligible patients in England.[43] A benchmarking exercise was completed across NHS Scotland identifying adult patient numbers prescribed mAbs as a proportion of the estimated severe asthma population (shown in Chart 8) showing wide variation in prescribing based on weighted population. A prevalence of 6.4% was assumed for asthma, based on the Scottish Public Health Observatory figures, and severe asthma estimated as 4% of this. Uptake and use of mAbs for the management of severe asthma varies across Scotland. Ongoing work is required to increase early identification, referral and assessment of at-risk patients.

Environmental considerations in severe asthma

A report published by the Sustainable Healthcare Coalition[44] estimated that the greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions associated with a person’s management of severe asthma is reduced by approximately 50% through the use of mAb therapy.

This reduction is due to the combined effects of improved symptom control, reduced exacerbations and a decrease in hospital admissions. These trends directly affect the environmental impact associated with asthma management and are important steps towards more sustainable treatment.

Asthma case study

Background Details - (Age, Sex, Occupation, baseline function)

- 47-year-old female

- Works as cleaner in local high school, but currently on sick leave

- Has had 16 courses of oral prednisolone therapy in 12 months without any face-to-face review with a clinician.

- Has ordered 24 salbutamol pMDIs in 12 months

- Breathless, nocturnal wheeze most nights

- Never tested positive for Covid

History of presentation/ reason for review

Referred to primary care healthcare professional due to OCS use and high-volume ordering of salbutamol, despite current treatment with Airflusal® pMDI (fluticasone 250 micrograms /salmeterol 25 micrograms) two puffs twice daily. Worsening symptoms over the past year. Multiple courses of oral prednisolone therapy

Current Medical History and Relevant Comorbidities

Asthma

Current Medication and drug allergies (include OTC preparation and Herbal remedies)

- Airflusal® pMDI 250/25 two puffs twice daily, only ordered six inhalers in 12 months

- Salbutamol pMDI two puffs, as required, 24 inhalers ordered in 12 months

Lifestyle and Current Function (inc. Frailty score for >65yrs) alcohol/ smoking/ diet/ exercise

- Lives with husband and three children. Has two dogs and one cat.

- Current smoker of 10 cigarettes per day with 18 pack years

- Overweight with BMI 31. Little motivation to engage with physical activity

Results e.g. biochemistry, other relevant investigations or monitoring

- Asthma Control Test (ACT) 7/25

- RadioAllergosorbent Test (RAST) – High positive dogs, moderate positive cats, low positive pollen, dust mite. Await Total IgE and aspergillus serology.

- Normal eosinophils. TFTs, FBC, U and Es, Bone, Glucose, ANA, ANCA, CRP, Iron studies and B12- normal.

- Referred Chest X-Ray (CXR) and Pulmonary function tests (PFTs)

Most recent consultations

First consultation:

- Discussed symptoms and ACT 7/25. Carried out full asthma serology screen. Referred for full PFTs, CXR and DEXA scan

- Chest exam-NAD. SpO2 98% room air

- Discussed concerns over multiple prednisolone courses, high volume salbutamol use and poor adherence to Airflusal® in the context of symptoms and ACT score, adherence to preventer therapy discussed

- Agreed move to Fobumix® Easyhaler® DPI (budesonide 320 micrograms/ formoterol 9 micrograms) two puffs twice daily and Easyhaler® salbutamol, as inhaler technique poor with MDI and good with Easyhaler®. Discussed this in line with health board’s green agenda. Discussed physiology of asthma and concerns, as identified as at risk

- Explained side effect risks from prednisolone and need for DEXA scan

- Discussed smoking cessation and Very Brief Advice (VBA) given. Will consider referral to Quit Your Way

- Full asthma screen and review arranged for following week

Follow up appointment:

- Given blood results and awaiting Total IgE and Aspergillus serology. Discussed addition of montelukast given RAST positivity and pets. Agreed with plan.

- Awaiting date for PFTs and CXR

- Further education and discussion around managing asthma.

- Aware dependent on awaited results may need referral onto Difficult Asthma Clinic

- Personalised Asthma Action Plan discussed, agreed and written copy issued. Advised that this may change dependent on results

- Further appointment made for four weeks for review

| Step: | Process: | Person specific issues to address: |

|---|---|---|

1. Aims What matters to the individual about their condition(s)? |

Review diagnoses and identify therapeutic objectives with respect to:

|

|

2. Need Identify essential drug therapy |

Identify essential drugs (not to be stopped without specialist advice)

|

|

3. Need Does the individual take unnecessary drug therapy? |

Identify and review the (continued) need for drugs

|

|

4. Effectiveness Are therapeutic objectives being achieved? |

Identify the need for adding/intensifying drug therapy in order to achieve therapeutic objectives

|

|

5. Safety Does the individual have ADR/ Side effects or is at risk of ADRs/ side effects? Does the person know what to do if they’re ill? |

Identify individual safety risks by checking for

|

|

6. Sustainability Is drug therapy cost-effective and environmentally sustainable? |

Identify unnecessarily costly drug therapy by

Consider the environmental impact

|

|

7. Person-centredness Is the person willing and able to take drug therapy as intended? |

Does the person understand the outcomes of the review?

|

Agreed plan

|

Contact

Email: EPandT@gov.scot

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback