Respiratory conditions - quality prescribing strategy: improvement guide 2024 to 2027

Respiratory conditions are a major contributor to ill health, disability, and premature death – the most common conditions being asthma and COPD. This quality prescribing guide is designed to ensure people with respiratory conditions are at the centre of their treatment.

6. Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD)

COPD

An estimated 1.2 million people live with diagnosed COPD in the UK, and the prevalence of COPD in Scotland is higher than the UK national average.[45] COPD is a disease of breathlessness, more common in those aged over 35 and in those with a risk factor, most commonly smoking or a history of smoking.[46] It is a major cause of morbidity and mortality and is a long term condition, which is set to increase in prevalence due to ageing and continued exposure to risk factors.[47]

Summary of recommendations in COPD

- ICS (licensed only as part of combination therapy (with LABA and/or LAMA)) are prescribed for people with COPD who have a severe exacerbation, features of asthma or more than 2 exacerbations in one year.

- review patients three months following initiation of inhaled ICS as part of combination therapy and stop ICS if there is insufficient response or adverse effects

- mucolytic therapy is considered for symptoms of chronic cough with productive sputum and should be reviewed four weeks after commencing therapy, stopping if symptoms have not improved with use

- regular review of mucolytic therapy during the annual COPD review should be undertaken and may be stopped if there is no productive cough

- review individuals with COPD on separate LAMA and LABA / ICS inhalers and, if appropriate, change to triple therapy inhalers

- review antibiotic course length (five-day course recommended) if needed for infective exacerbations of COPD, with sputum cultures for treatment failure

- repeated use of 'rescue medication' (steroid and/or antibiotic) (two or more courses per year) should trigger a review to optimise long-term management

Principles of prescribing for COPD

Removal or reduction of risk factors, such as stopping smoking is the first step to management of COPD. Breathlessness in COPD is managed with long-acting bronchodilation. GOLD[47] and NICE guidance recommend dual bronchodilation, although in clinical practice often single agent long-acting bronchodilation is used. Prescribers should be guided by local formulary guidance. Inhaled therapy aims to relieve the symptoms of breathlessness in COPD. Pharmacotherapy can reduce COPD symptoms, reduce the frequency and severity of exacerbations, and improve health and exercise tolerance.[47] Patients with COPD should be reviewed regularly to ensure that treatment is optimised.

Inhaler device selection is important, and patients should receive training in how to use the device and be able to use it. Sufficient inspiratory flow is needed for a dry powder inhaler (DPI) and if an individual can breathe in quickly and deeply over two to three seconds, they are likely to be able to manage a DPI. Those who are frail, elderly or the very young are less likely to have sufficient inspiratory flow and an MDI with spacer may be more appropriate. Environmental impact of inhalers is a key consideration and prescribers are asked to consider inhalers with a lower global warming potential where it is appropriate for the patient (see chapter 10).

To prescribe most effectively for individuals with COPD the ‘what matters to you?’ principles and Polypharmacy 7-Steps approach are recommended. Table 2 outlines the main principle for treating patients with COPD.

Table 2: Principles of treating patients with COPD

Polypharmacy review 7-Steps

1 What matters to the patient?

- Ask the patient what matters to them?

- Ask patient to complete PROMs (questions to prepare for my review) before their review

- Is the patient’s day to day life or activities affected?

- Do they have relief of symptoms and would they like to consider prevention of deterioration or repeat attacks.

- Clear guidance and advice on when to use rescue medication – this may involve the use of digital technology (e.g. COPD self-management app)

- How to improve activity and exercise tolerance and the introduction of pulmonary rehabilitation to improve quality of life at the appropriate point. Advice regarding pacing and lifestyle

- Knowledge of and avoidance of known triggers for exacerbations, e.g. infection.

- Do environmental considerations matter? (see chapter 10)

2 Identify essential drug therapy

- Ensure COPD diagnosis confirmed by spirometry carried out by trained professionals

- Check adherence and inhaler technique before stepping up or adding medicines

- Ensure treatment is optimised with local / GOLD guidelines47

- When considering therapy, note when patients may have COPD with a background of asthma

- Acute COPD exacerbations, defined as a sustained worsening of respiratory symptoms with acute onset, from their usual stable state beyond normal day-to-day variations, usually triggered by a respiratory tract infection. Initial treatment is with SABA. Consider the use of oral corticosteroids (OCS) with the possibility of antibiotics if indicated, for five days following the local formulary and personalised self-management plan[48]

- Indication for antibiotics (three of the following symptoms, or only one additional symptom if change in sputum colour is present)47

- worsening breathlessness and

- cough

- increased sputum production

- change in sputum colour

- Indication for antibiotics (three of the following symptoms, or only one additional symptom if change in sputum colour is present)47

- For regular exacerbations, consider referral to secondary care where recommended antibiotic prophylaxis may be prescribed, referring to local formularies for guidance. Consider risk-benefit due to increased bacterial resistance.[47],[49]

- Monitoring during antibiotic therapy may be required46

- Secondary care review to confirm ongoing need for and effectiveness of medication and screen for side effects

3 Does the patient take unnecessary drug therapy?

- Review use of ICS as part of combination therapy in people with COPD who are not exacerbating or who do not have blood eosinophils >300 cells/μL to reduce the risk of pneumonia and other potential ADRs[47]

- Long term OCS are not recommended due to the potential for adverse effects

- Steroid treatment cards should be provided to patients on high dose steroids (both oral and inhaled). A steroid emergency card may also be required.[18]

- Ordering six or more SABA inhalers per year may indicate continued breathlessness and therapy optimisation may be needed

- Repeated use of ‘rescue medication’ (two or more per year)[47] should trigger a review to optimise long term management. Sputum samples are necessary to guide antibiotic prescribing, especially if empirical prescribing has not resolved symptoms.[47]

- Review the need for mucolytics on a regular basis and continue only if symptomatic improvement (reduction in cough and sputum)[48]

- Regular use of nebuliser therapy should be a prompt for review. Nebulisers should only be used under medical recommendation. They require regular servicing and a pMDI with a spacer is at least as good as a nebuliser in treating mild / moderate asthma attacks6

- If oxygen saturations are below 92% on air consistently, refer for oxygen assessment as per local Health Board criteria

- Patients with significant emphysema and air trapping may benefit from lung volume reduction surgery

4 Are therapeutic objectives being achieved?

- Ensure at least annual review

- Can the patient use their inhalers properly? Consider addition of spacer to aid MDI lung deposition or consider DPI/SMI if appropriate

- Improvement in general health and exercise tolerance

- Reduction in breathlessness and reduction of the risk of exacerbations or hospital admissions

- Use COPD Assessment Test (CAT)[50] and/or Modified Medical Research Council (MRC) breathlessness scales[51] score as objective measurements of effect on activities of daily living (ADLs)

- Optimise therapy if there are frequent exacerbations and update self-management plans.

- Manage comorbidities affecting management and symptoms of COPD e.g., depression, heart failure, osteoporosis, obesity, anxiety and dysfunctional breathing

- Vaccinations should be offered if not up to date (influenza, pneumococcal, DTaP (if not vaccinated in adolescence) and Covid-19)

- Patients should be encouraged to engage in appropriate physical activity, including pulmonary rehabilitation. Social prescribing such as exercise, dependant on ability and singing classes

- Smoking cessation should be advised and the adverse effects of smoking on children highlighted. Offer appropriate support. Signpost patients to the NHS inform Quit Your Way Scotland website (which includes community pharmacy services) Weight reduction is recommended in obese patients (BMI >30)

- Nutritional advice and support will be necessary in those with a BMI less than 20

5 Is the patient at risk of Adverse Drug Reactions (ADR)s or suffer actual ADRs?

- Appropriate use of ICS as part of combination therapy ensures reduced risk of developing pneumonia (low eosinophil counts are predictive of increased risk of pneumonia) and adrenal suppression[47]

- Oral corticosteroid use should not be used routinely unless comorbidity diagnosis requires OCS treatment. If withdrawal not possible, prescribe the lowest possible dose. Monitor for the possibility of adrenal suppression/ glucocorticoid effects and osteoporosis if on long term or frequent (more than three or four courses a year) treatment[19]

- Assess for oral thrush - ensure correct technique to reduce incidence and add spacer device for pMDI if required

- Dry mouth is common due to anticholinergic effects of long-acting muscarinic antagonist (LAMA) inhalers.

- Antibiotic use may cause adverse effects including potential allergies and are not suitable for all COPD exacerbations. Minimal course length should be prescribed to reduce the risk of resistance. Ensure true antibiotic allergies are recorded and review accuracy of previous records. Scottish Antimicrobial Prescribing Group (SAPG) have a penicillin de-labelling toolkit.[52]

- Yellow card reporting of ADRs

6 Sustainability

- Triple therapy may be more cost effective compared to using separate long-acting beta2 agonist (LABA)/ LAMA and ICS inhalers and aids adherence as well as reducing the carbon footprint of the inhalers (single versus multiple inhaler use)

- Consider whether a DPI or SMI would be appropriate

- Opportunities for cost minimisation should be explored but only considered if effectiveness, safety or adherence would not be compromised

- For new medicines ensure prescribing is in line with Health Board formulary recommendations

7 Is the patient willing and able to take drug therapy as intended?

- A personalised action plan is a key factor, with focus on inhaler technique, worsening symptom advice and awareness of symptom control.

- Refer to Pulmonary Rehabilitation (PR) or physiotherapist management of dysfunctional breathing, when necessary, as per local Health Board criteria.

- Consider end-of-life and palliative care support. Does the patient have an Anticipatory Care Plan (ACP)?

- Make patient aware of support information e.g. the My Lungs My Life website (See Appendix 1)

- Agree with the patient arrangements for repeat prescribing. Signpost to Medicines Care and Review (MCR) service in community pharmacy where appropriate

- Ask patient to complete the post-review PROMs questions after their review

Prescribing areas to address for COPD

The indicators included are priority areas of prescribing where there is variation within NHS Boards. Ensuring COPD medicines are reviewed and optimised may support the reduction of unwarranted variation. The indicators focus on ensuring quality prescribing and any recommendations made follow national clinical guidance. PIS Prescribing data cannot be separated by diagnosis however the Scottish Therapeutics Utility (STU) software enables GP practices to identify patients with asthma or COPD (see chapter 12).

Prescribing of inhaled high dose corticosteroids

The place of inhaled corticosteroids as part of combination therapy has been revised.[47] For people with COPD who are at high risk of exacerbations, based on blood eosinophils of ≥300cells/μL, initial treatment with triple therapy (inhaled ICS plus LABA and LAMA) is recommended by GOLD.[47] In addition, escalation to triple therapy is recommended if exacerbations occur in patients with blood eosinophils ≥300 cells/µL receiving monotherapy or patients with blood eosinophils ≥100 cells/μL receiving LABA + LAMA.[53] If people with COPD also have a diagnosis of asthma, they should be treated according to treatment guidelines for asthma, with ICS.[47]

ICS (licensed only as part of combination therapy (with LABA and/or LAMA) are prescribed for people with COPD who have a severe exacerbation or more than two exacerbations in one year or if there are asthmatic features or features suggesting steroid responsiveness.[47] ICS provide some benefit to patients with severe COPD, reducing exacerbations by 20-25% however there is a dose dependant risk of side effects (including pneumonia and osteoporosis). Clinical review following initiation of ICS should be undertaken after three months and ICS stopped if there is insufficient response or if there are adverse effects.[46] A blood eosinophil count ≥300 cells/microlitre is more likely to cause relapse or exacerbations if ICS is withdrawn and needs to be monitored carefully. Refer to local guidelines to optimise treatment.

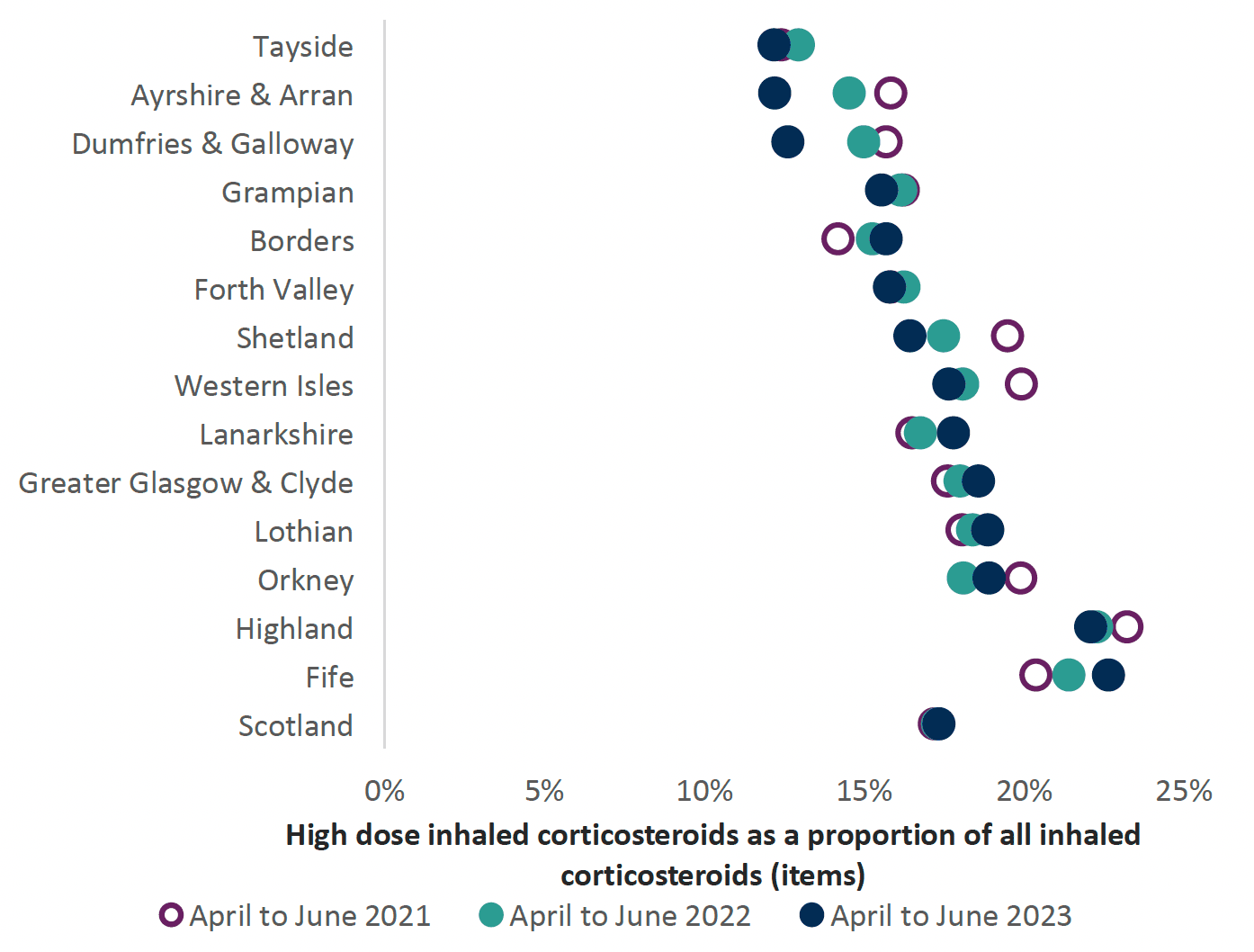

The chart below shows the variation in inhaled high dose corticosteroids between NHS Boards over the last three years. The high dose classification is based on SIGN 158.[6]

*High dose ICS prescribing used in the data corresponds to the definition of high dose steroids (both for adults and children) as per Table 12 in SIGN 158.[6]

Prescribing of Mucolytics

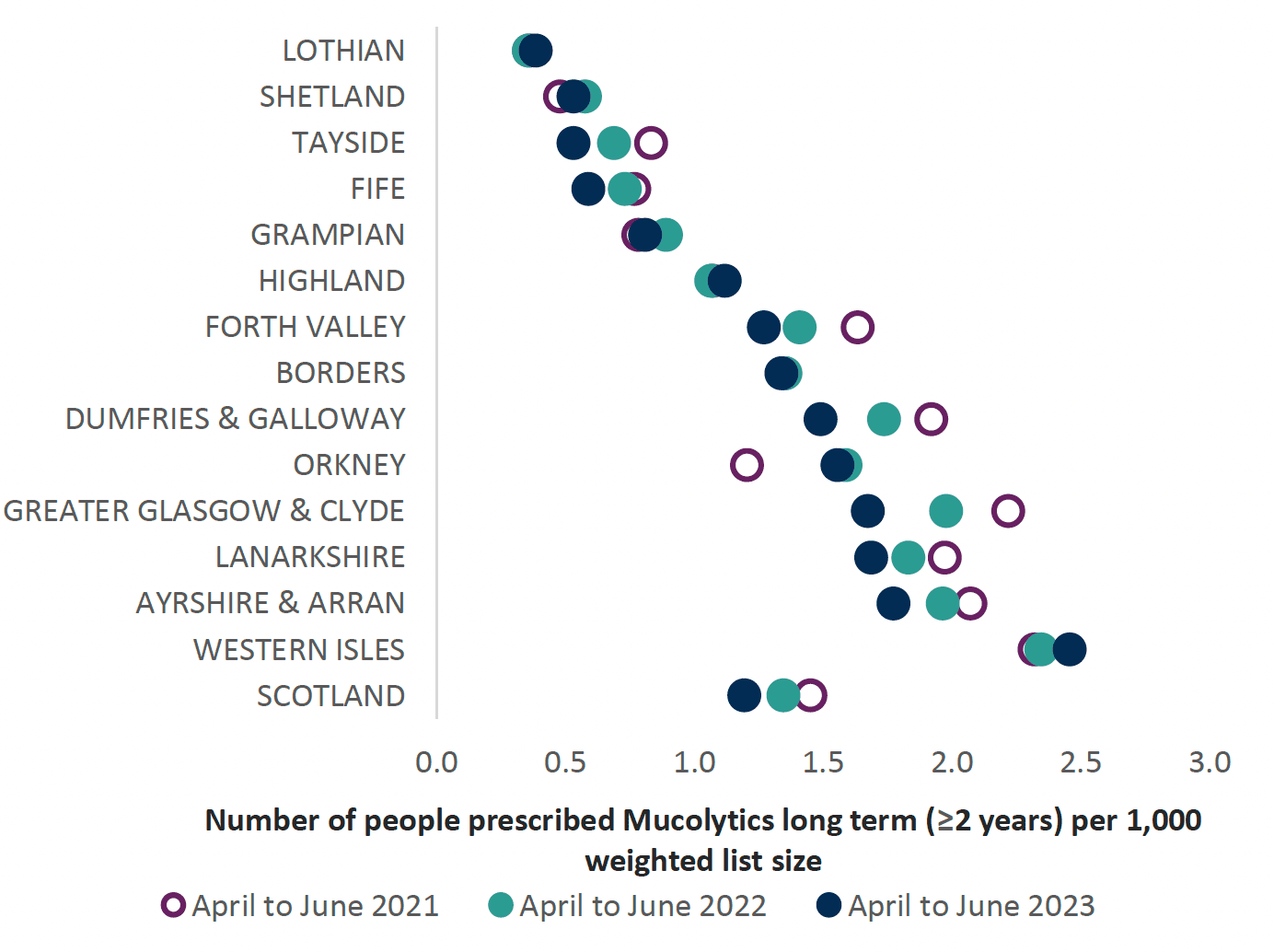

Mucolytics are taken orally to assist patients coughing up sputum, as it breaks down the protein bonds, ‘loosening’ the mucus. A recent Cochrane review found that use of mucolytics may reduce the likelihood of an acute exacerbation, reduced days of disability per month and possibly reduced hospital admissions with minimal adverse effects. There is doubt in the confidence of early trials reviewed in the results, due to possible risk of bias in selection or publication, therefore the benefits of treatment may not be as great as suggested.[54] Mucolytics do not appear to affect health related quality of life or improve lung function. NICE has previously recommended that mucolytics should not be routinely prescribed to prevent exacerbations for patients with stable COPD. Mucolytic drug therapy may be considered for people with a chronic cough productive of sputum.[46]

Mucolytic therapy should be reviewed after a four-week trial and stopped if symptoms of cough and sputum production have not improved. Regular review of mucolytic therapy should be undertaken during the annual review and may be stopped if there is no productive cough or if symptoms have not improved with use.[48] This review could be completed in primary or secondary care.

Prescribing of Triple therapy

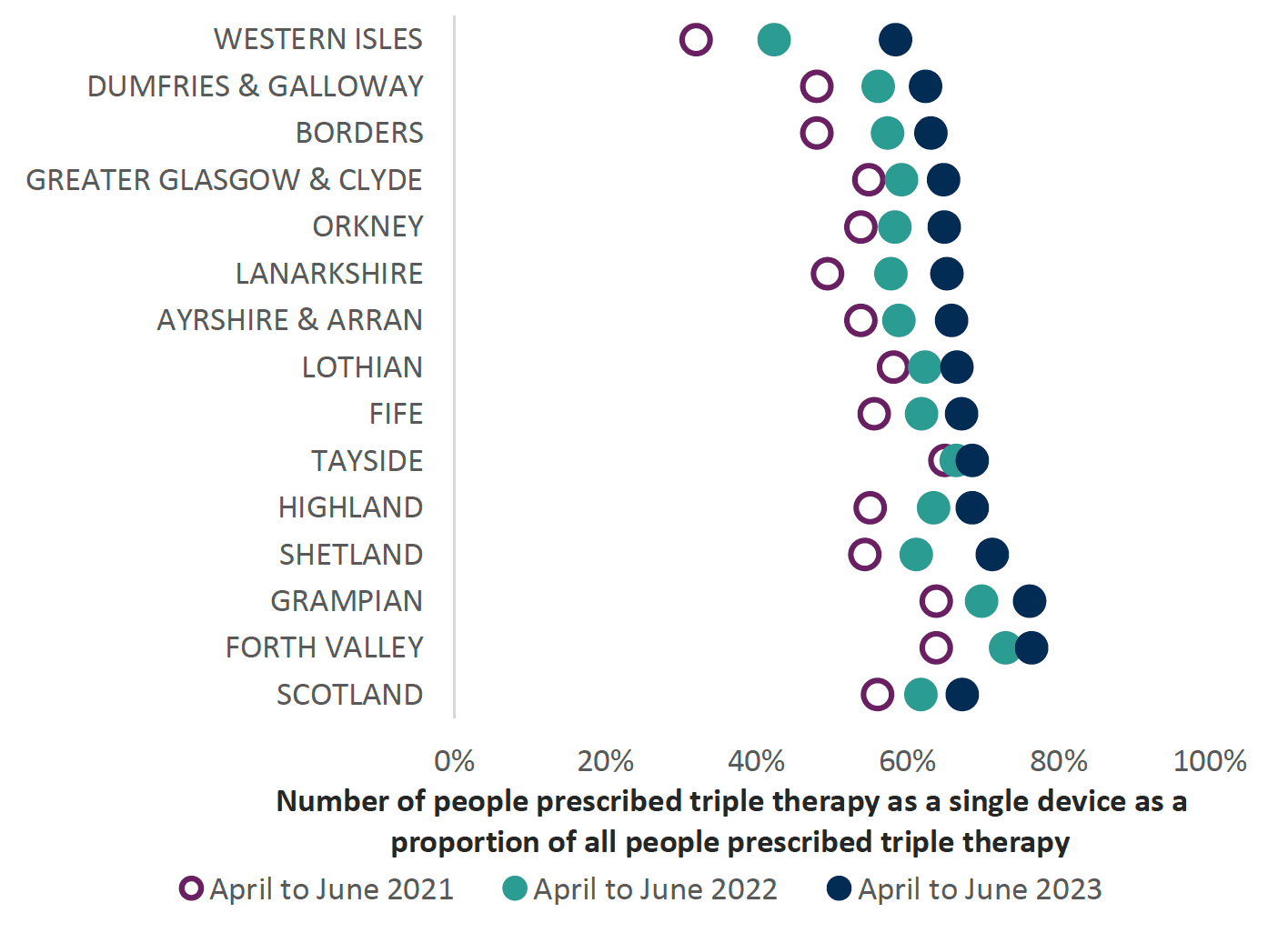

Triple therapy has been shown to improve lung function and patient related outcomes as well as reduce exacerbations compared with LABA alone, LABA/LAMA and LABA/ICS inhalers.[47] Triple therapy may be suitable for patients with COPD who are experiencing exacerbations or for those with COPD with a background of asthma and still experiencing symptoms or exacerbations. Use of triple therapy inhalers should increase adherence by patients, is cost effective and will have a reduced carbon footprint versus multiple inhalers.

Lifestyle aspects of therapy should be optimised when considering a move onto triple therapy. This includes smoking cessation as well as excluding other potential causes of breathlessness or poor control (adherence, inhaler technique). A clinical review after three months is recommended in order to assess benefit from the triple therapy, discontinuing the ICS if there is no improvement.[46] This review can be completed in primary or secondary care.

The current triple inhalers Trelegy® Ellipta®, Trimbow® (MDI and Nexthaler®), Trixeo® Aerosphere® and Enerzair®Breezhaler® have differences in licensed indication [55], [56], [57], [58], [59], [60] outlined in Table 3 below. See individual Summary of Product Characteristic (SPC) for licence details. The information in Table 3 was correct at the time of publication.

| Triple inhaler | Licensed for asthma | Licensed for COPD |

|---|---|---|

| Enerzair® Breezhaler® (indacaterol 114 micrograms / glycopyrronium 46 micrograms / mometasone 136 micrograms)[55] | Yes | No |

| Trelegy® Ellipta® (fluticasone 92 micrograms/ umeclidinium 55 micrograms/ vilanterol 22 micrograms)[56] | No | Yes |

| Trimbow® pMDI (beclomethasone 87 micrograms/ formoterol 5 micrograms/ glycopyrronium 9 micrograms)[57] | Yes | Yes |

| Trimbow® pMDI (beclomethasone 172 micrograms/ formoterol 5 micrograms/ glycopyrronium 9 micrograms)[58] | Yes | No |

| Trimbow® NEXThaler® (beclomethasone 88micrograms / formoterol 5 micrograms / glycopyrronium 9 micrograms)[59] | No | Yes |

| Trixeo® Aerosphere® (formoterol 5 micrograms / glycopyrronium 7.2micrograms/ budesonide 160 micrograms)[60] | No | Yes |

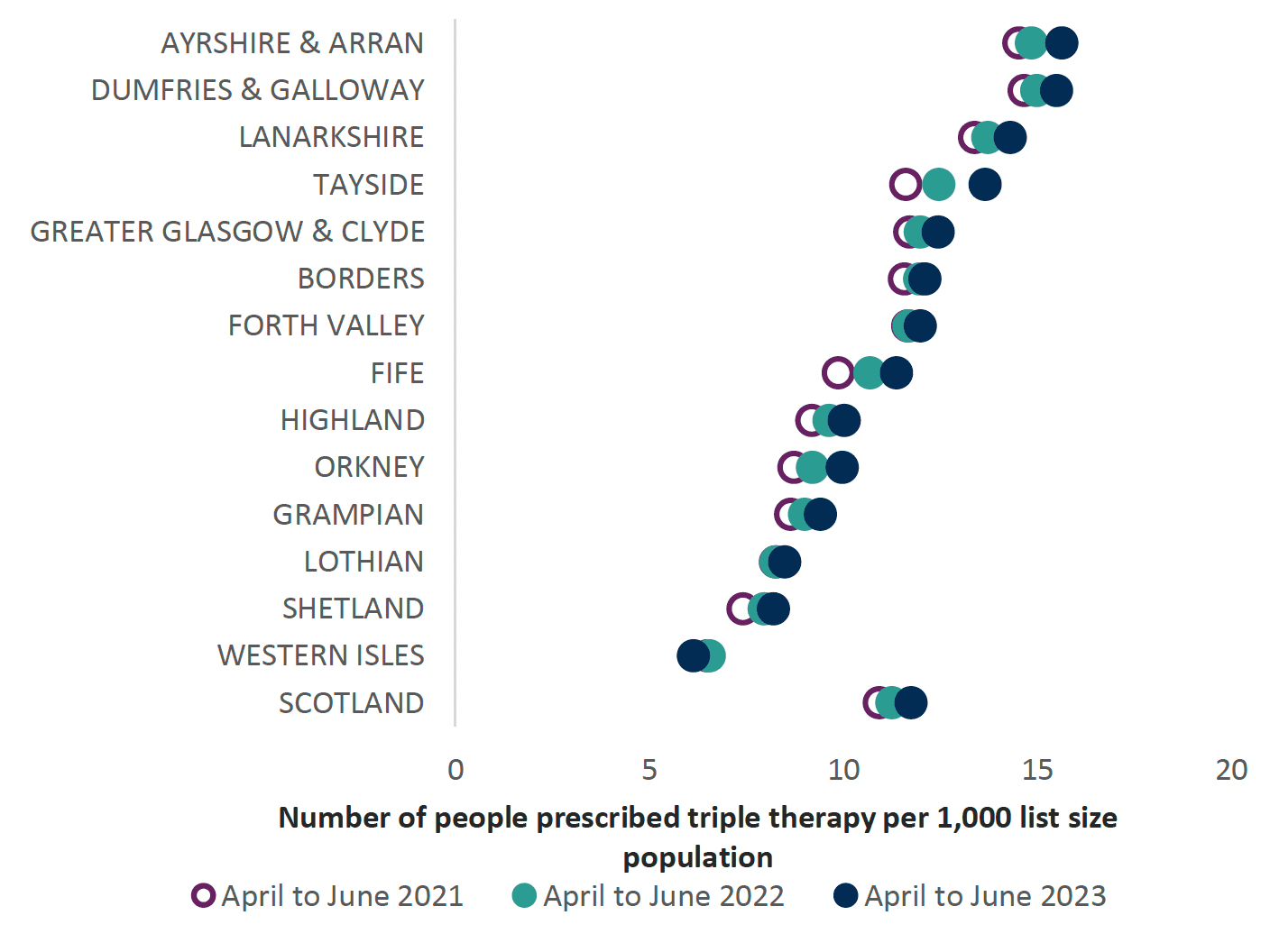

Chart 10 below illustrates the use of triple therapy prescribing, as either separate inhalers or as a single triple inhaler, showing wide variation between NHS Boards, ranging from 15.63 in Ayrshire & Arran to 6.13 in the Western Isles. This may vary with prevalence of COPD within board regions.

The chart below shows the individual inhaler prescribing per Health Board which potentially could be prescribed as a combination inhaler (noting that there may not be an exact equivalent available as a triple therapy inhaler).

Treatment of Exacerbations

A range of factors may trigger an exacerbation, for example, a viral infection or smoking. Only half of exacerbations are caused by bacterial infection.

Oral corticosteroids, at a dose of 30mg for five days,[46] should be considered for people with COPD with an exacerbation causing breathlessness which is interfering with their usual day to day activities, unless they are contraindicated.

An antibiotic may sometimes be necessary for an acute exacerbation of COPD, depending on factors such as severity of symptoms, including purulence of sputum, previous exacerbations or hospital admissions and risk of complications. Five-day courses of antibiotics are recommended as this is effective, reduces risk of resistance and minimises adverse effects.

Treatment failure with antibiotics requires a sputum culture before prescribing further antibiotics. If symptoms worsen despite antibiotic therapy, other causes must be investigated, e.g. pneumonia.[48]

COPD case study

Background (Age, Sex, Occupation, baseline function)

- 51-year-old male

- Self-employed businessman

History of presentation/ reason for review

- Orders at least two Salbutamol pMDIs per month, therefore highlighted for a respiratory review with a primary care healthcare professional

Current Medical History and Relevant Comorbidities

- Salbutamol pMDI originally started about three years ago, for occasional breathlessness

- No confirmed respiratory diagnosis

- No other medical history of note

- No allergies

- No family history of respiratory conditions

Current Medication and drug allergies (include OTC preparation and Herbal remedies)

- Salbutamol pMDI, inhale two puffs when required for breathlessness

Lifestyle and Current Function (inc. Frailty score for >65yrs) alcohol/ smoking/ diet/ exercise

- Smokes 20 a day including regular cannabis use

- Drinks alcohol on a regular basis, at least six units a day (shares a bottle of wine with his partner most days)

- Sedentary lifestyle, ‘No time to exercise’ due to pressures of work

“What matters to me” (Patient Ideas, Concerns and Expectations of treatment)

- Wants to improve his symptoms of breathlessness and does not see the problem with use of frequent salbutamol

- Patient acknowledges stress of job and smokes to relieve this, clearly states that he cannot stop

Results e.g biochemistry, other relevant investigations or monitoring

- Spirometry reversibility testing confirmed diagnosis of COPD (FEV1/FVC ratio 66)

- Sats on air 97%

- BMI 28

- MRC score 2

Most recent relevant consultations

- Commenced regular long-acting bronchodilator therapy, tiotropium in a soft mist inhaler (tiotropium and olodaterol Respimat®), demonstrating inhaler technique and explaining the need to order refills every month and to replace the device every six months, for environmental reasons.

- In addition, offered the option to change to a salbutamol DPI for environmental reasons as well as the presence of a dose counter. Checked inhaler technique and changed to Easyhaler® Salbutamol.

- Organized influenza and pneumococcal vaccination

- Encouraged to stop smoking. The patient was not keen to do this at the present time due to ongoing stress at work but acknowledged the need to think about this. Signposted to the Stop smoking service at the local community pharmacy for the time he is ready to quit. In the meantime, advised to reduce amount smoked, particularly in relation to cannabis.

- Discussed stress management strategies including making time for some cycling and swimming which he was keen to do. Increased activity will also help with lung function, pulmonary rehabilitation may be appropriate for referral in the future. Acknowledges that he needs to make time to do this.

- Also highlighted problem alcohol drinking and advice to have two alcohol free days at least.

- Issued with a COPD management plan so that symptoms of exacerbations were clear and actions to follow in that case were explained.

| Step | Process | Person specific issues to address |

|---|---|---|

1. Aims What matters to the individual about their condition(s)? |

Review diagnoses and identify therapeutic objectives with respect to:

|

|

2. Need Identify essential drug therapy |

Identify essential drugs (not to be stopped without specialist advice)

|

|

3. Need Does the individual take unnecessary drug therapy? |

Identify and review the (continued) need for drugs

|

|

4. Effectiveness Are therapeutic objectives being achieved? |

Identify the need for adding/intensifying drug therapy in order to achieve therapeutic objectives

|

|

5. Safety Does the individual have ADR/ Side effects or is at risk of ADRs/ side effects? Does the person know what to do if they’re ill? |

Identify individual safety risks by checking for

|

|

6. Sustainability Is drug therapy cost-effective and environmentally sustainable? |

Identify unnecessarily costly drug therapy by

Consider the environmental impact

|

|

7. Person-centredness Is the person willing and able to take drug therapy as intended? |

Does the person understand the outcomes of the review?

|

Agreed plan

|

Contact

Email: EPandT@gov.scot

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback