Realistic Medicine - Taking Care: Chief Medical Officer for Scotland annual report 2023 to 2024

This is the Chief Medical Officer Professor Sir Gregor Smith's fourth annual report, and the eighth report on Realistic Medicine. The overarching aim of Realistic Medicine is to deliver better value care for patients, and for our health and care system.

Chapter 1: Taking Care of Our People

Careful and kind care

What is “care”? What do we mean when we talk about “receiving care”? Do we mean healthcare? Social care? Spiritual care? Loving or romantic care? At different times for different people, it may be any or all these things. All these elements of care contribute in some way to enhancing the quality and the experience of our life, our wellbeing, or to alleviate some of the pain or discomfort of negative experiences we inevitably face.

Care should mean alleviating or easing of this pain, even in the most difficult or challenging of moments. It should be given for the purpose of aiding; perhaps not always exactly what is sought, and often not intending to cure, but compassionately judged, nonetheless. It should recognise with full fidelity the unique circumstances of the people we care for, be mindful of the encumbrance, however well intentioned, it may place upon them, and be informed by careful conversations that enable this understanding.

The Cambridge Dictionary defines care as “the process of protecting someone or something and providing what that person needs”. This definition feels limited in our context. It suggests a paternalistic response, reducing agency and diminishing necessary wider holistic considerations. It feels like the imperfect model of healthcare, well-intentioned but ultimately falling short of what is required for the complex concept of health and wellbeing we pursue.

Fisher and Tronto suggest that care is “everything that we do to maintain, repair and improve our ‘world’ so that we can live in it as well as possible”. Engster builds on this, suggesting “caring is everything we do directly to help individuals satisfy their basic biological needs, develop or maintain their basic capabilities, and avoid or alleviate pain and suffering”. This encapsulates wider positive contributions to our health and wellbeing from beyond traditional concepts of caring; activities like cooking, our participation in the arts, or being in green spaces. This helps to provide coherence to our lives and roots us to a sense of ease from which the conditions for achieving health are developed.

Care is not then solely about healthcare or social care, though these are important components of a society in which care flourishes. Our health and care systems, like many others across the world, have responded to rising demand and pressure by taking new approaches – by innovating and improving and by pursuing efficiency. However, we must beware of focussing solely on the pursuit of efficiency. A reductionist approach may reduce measurable costs at the expense of difficult-to-measure benefits.

Likewise, performance measures are incompletely suited to managing or controlling the way we deliver care. I agree with Mintzberg’s contention that treating people or managing risk in specialties such as general practice, or psychiatry, where so much of “care” cannot be measured, is not suitable for approaches such as this. Some of the highest quality care, using these wider definitions, comes from compassionate conversations that address concerns, issues or distress and manage risk without quantitative record of the benefits that are derived to individuals and to society. It is a mistake to assume that all healthcare can be managed in the same way as other industries, through the pursuit of increased productivity and by minimising costs.

If we attempt to do this, to design and promote a system of transactional care, we run the risk of losing the art of care – the human connection that makes care caring – and promoting moral injury to our staff.

We must continue to seek novel approaches – to consider how we can update and evolve our practice. We need to make space for conversations about what realistic care looks like. This means finding out what matters – to understand people and their circumstances – and then doing what matters.

Outcomes that matter

I want to see this biographical understanding of people translated into personalised care that people value. This approach sits at the heart of a culture of Value Based Health and Care — where care is both careful and kind.

Careful care is founded on principles of quality, safety and the tailored use of best available evidence. More importantly, this approach means considering a person’s health conditions in the context of their unique circumstances and priorities, not just their biological data.

Kind care means having respect for a person’s most precious resources – their time, energy and attention – and making sure that healthcare’s footprint upon these resources is minimally disruptive.

I was pleased to find these principles embedded in the General Medical Council’s updated Good Medical Practice, which says that we “must treat patients with kindness, courtesy and respect”. These very human ideas are integral to our practice, but I know from my own experiences that meaningful kindness in care is complex. I recognise that the act of being kind can come easily when we are well-rested, well-nourished, supported and feeling valued. It can feel difficult when our intentions meet the at-times overwhelming realities of clinical and care practice.

While careful and kind care are central to what it means to be a healthcare professional, this not something that can be imposed. The role of our organisations and leaders is to foster an environment where careful and kind care can flourish through meaningful conversations with the people we care for. I would go further and suggest that leadership, though important, is not enough by itself and “communityship” is what is needed within the organisations and teams that we work. As Mintzberg says, “effective organisations are communities of human beings, not collections of human resources.”

Collaboration between professionals where vested interests and prerogative are set aside is vital. Healthcare is a vocational career, a “calling” for many of us, especially for those who feel the privilege of serving their local communities. We must ensure that our health and care professionals are provided with the support to enable this sense of service to thrive. To belong and to be valued as part of something much bigger; that contributes meaningfully and cares for society.

“Nobody cares how much you know, until they know how much you care”

Theodore Roosevelt, US President and conservationist

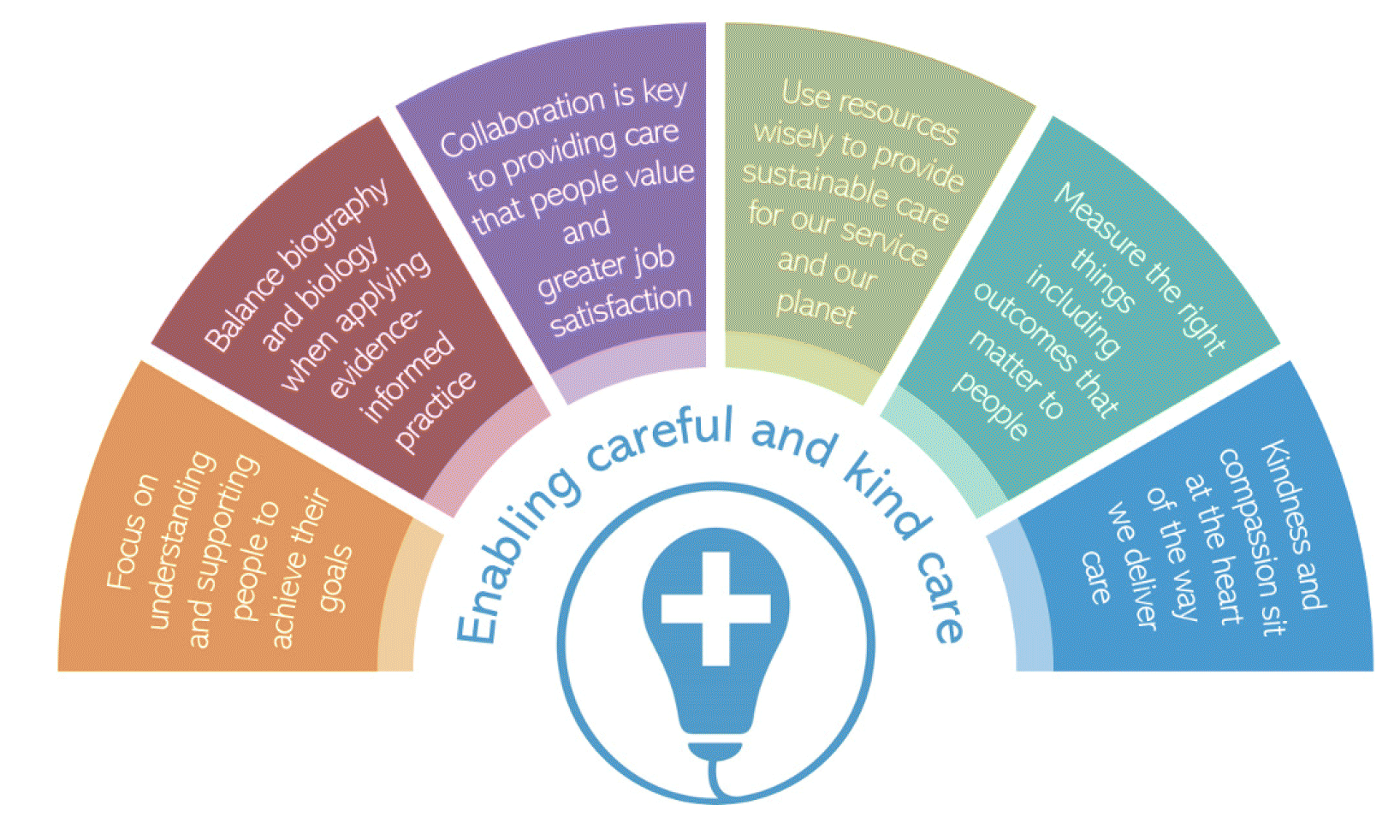

People need to feel a sense of genuine care from others before they are willing to listen, learn or be influenced by their knowledge. Embedding these six principles in the organisations that we work will enable us to practise the way we wish to practise and deliver careful and kind care:

Taking a careful and kind approach to healthcare, NHS Forth Valley’s framework for type 2 diabetes prevention, early detection and intervention links healthcare professionals with other cross-sector community support mechanisms to provide the right support tailored to the individual. The local diabetes team are working in an area with high levels of social and economic deprivation, discussing each person’s priorities, listening to their stories and helping them navigate the complex networks of services using current staffing and resource. They have taken a Human Learning System approach with important lessons for others seeking to establish community services.

Human Learning Systems in NHS Forth Valley

Human

People’s priorities are often different from those of healthcare professionals. People put the needs of their family above their own health needs, with household dynamics influencing engagement and outcomes. Person-led conversations can encourage healthy awareness and management of behaviour drivers. Shared local knowledge, understanding and connection empower people to form relationships with healthcare professionals.

Learning

Rapid access to “key actors” builds trust and reduces anxiety. Diverting from standard practice to support personal outcomes critical.

Systems

Traditional healthcare tends not to consider social complexity and its impact on outcomes. Embedding a human approach throughout healthcare requires system change.

Jim’s Story

The benefits of this very human approach are clear. Take the example of Jim, who was referred to the NHS Forth Valley team as part of a pre-diabetes pathway. A human-human conversation clarified that his key concern at that moment in time was not diabetes – it was weight loss.

The team could have delivered pre-diabetes counselling and referred him on to other services. However, they chose to find out and focus on what mattered to Jim: investigating and supporting him with his weight loss promptly, locally and with the involvement of his family.

This approach of doing what matters, rather than strictly abiding by the traditional limits of the services we offer, meant that Jim avoided multiple onward referrals, potentially lengthy waits for appointments and the associated stress and uncertainty. This team has been working creatively and with great care to deliver outcomes that matter to the people they care for.

Taking care of our population

“Care is the most important social determinant of health”

Victor Montori

So what of this broader concept of care as it relates to the very real challenges we face? Health inequalities are one of the defining issues of our time and are woven through every health challenge Scotland’s population faces.

Over the next 20 years, the Scottish Burden of Disease study projects that illness will rise by 21%. Health and wider societal inequalities, along with an ageing population, will see this increase in illness fall disproportionately on a smaller population. To turn the tide, we need radical reform focussed on prevention and the fundamental building blocks of a healthy life.

We know that most of the influences on health inequalities lie outside health and social care systems. A wide range of socioeconomic factors influence the pursuit of a healthy life and affect the underlying determinants of health, including food and nutrition, good housing, safe and healthy working conditions and a thriving natural environment.

As professionals, we must acknowledge that the greatest influence on an individual’s health is not the result of our work, but rather the wider circumstances of the individual. The core drivers of health inequalities are inequalities in income, wealth and power. People with lower incomes, or who are socially disadvantaged in other ways, can consistently expect to be in worse health than those with greater socioeconomic power in society. Those experiencing poverty, deprivation and prejudice exist within our health and care systems, and we need to acknowledge and act on this.

Health inequalities, human rights and the planetary crisis

In Chapter 2, I’ll share my thoughts on the unfolding planetary crisis. I think it’s important to highlight here that, directly and collectively, the planetary crisis is both a public health and a human rights crisis that will worsen existing inequalities and drive new forms of inequity.

We all have a right to a safe and sustainable environment. I am very proud that Scotland is taking its human rights responsibilities seriously and has shifted its focus to inter-generational justice. This year, we have taken the bold, proactive and historic step of enshrining children’s rights in law – through the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (Incorporation) (Scotland) Act. This is a lever to ensure that the best possible start in life is respected, realised and protected. This also sets a clear direction: to care for our natural environment for the benefit of future generations.

Stigma, discrimination, poverty, violence, complex trauma; people who are socially excluded and marginalised often experience these interacting risk factors for poor health. These factors do not occur randomly or by chance – they are socially determined, disadvantaging people and limiting their opportunities. We must continue work to establish a more equitable society, that recognises everybody has different circumstances but that acts to ensure everyone has access to the same opportunities.

While health and social care contribute only 20% of the modifiable determinants of health, meaningful care through a well-developed universal healthcare system is important. What we do matters. Successful action necessitates both intervening upstream – tackling fundamental whole-system and wider environmental causes of health inequity to ensure maximum reach – and intervening downstream – focussing on people’s own experiences and what matters to them.

Care goes beyond the relationship between us as health and care professionals and the people we care for. Our purpose is also to understand and support the wider communities of those we care for and the environment that sustains us. The evidence in Chapter 4 sets out some of the main factors driving inequalities in our society. In this chapter I’d like to share solutions which demonstrate how care can help tackle them. I’ll reinforce these approaches and share more examples of how care can impact positively on communities and our planet in Chapter 2.

Making healthy weight a priority

People living in less economically affluent communities are disproportionately burdened with the ill health and mortality linked to poor nutrition.

Cost-of-living pressures have put healthier food options out of reach for many. The foods we’d like to see in a varied and healthy diet can be twice as expensive per calorie compared to unhealthy foods. Those living with food insecurity would need to spend around half of their disposable income on food to meet the cost of the Eatwell Guide whilst food-secure households need only spend 11%.

As health and care professionals, we understand how a healthy diet is fundamental to healthy growth and development in children. Children’s chances of eating well depend strongly on where they grow up and those living in less affluent areas are more likely to be exposed to unhealthy food in their high streets, more likely to have the poorest diets and less likely to be a healthy weight.

The World Health Organization states that obesity cannot be seen simply as an issue of personal responsibility but as a critical health, economic and societal issue. It is a critical issue in Scotland too – where 1 in 3 children are at risk of overweight and obesity, and obesity affects 2 in 3 adults. We cannot afford to ignore this problem. Nesta estimated the cost of obesity to Scotland to be as much as £5.3 billion annually - of which £4.1 billion is the value lost to people through reduced quality of life.

Our most disadvantaged communities have fewer opportunities available to positively shape day-to-day health, not just through access to healthy food, but also safe and affordable opportunities for active travel and exercise.

This lack of opportunity worsens and embeds health inequalities, as these same communities are more adversely affected by overweight and obesity. We must support our population to make healthy eating choices, maintain a healthy weight and participate in regular physical activity. This is critical if we want to meaningfully tackle inequalities in our society.

Shared local spaces and local knowledge can help us take a broader approach to our social purpose as health and care professionals. Joining the communities we serve helps us to see the context of the people we care for, adding an essential biographical understanding to the care we provide.

I have been encouraged to see colleagues like the diabetes team in Ayrshire & Arran doing just that. With support from the Realistic Medicine Value Improvement Fund, they have established a weekly service in a community hub with a morning eye screening clinic, community treatment and care nurse clinic and drop-in services throughout the day. This is bringing care closer to home with better outcomes as a result – and represents a crucial opportunity to directly connect people’s diabetes management to support for the wider building blocks of good health.

The Dalmellington Community Health Hub

In Ayrshire, the Dalmellington Community Health Hub is a place where people can meet, talk with and receive support on everything from weight management, disease prevention and early intervention and smoking cessation, to financial, housing and energy advice. This is a community-driven group that focuses on human connection.

Co-locating eye-screening here has led to the highest uptake in NHS Ayrshire & Arran – improving from 70% to 89% — and low-risk foot screening has also improved from 9.1% to 36.1%. There is earlier detection of disease which means quicker time-to-treatment – the timely treatment of new foot ulcers has increased from 50% to 100%. Crucially, the team have also found that this gives them the opportunity to support people to adapt their lifestyles before more serious complications develop. This is care that is kind, thoughtful and realistic – doing what matters in the right way by bringing care closer to home.

Missingness in health and care

It will come as no surprise that, in an inequitable society and with a system under pressure, we sometimes fail to appreciate the time, emotional investment and disruption that comes with accessing healthcare. There is a misconception that when people do not engage with health and care services, they cannot need health and care services.

But “missingness” – the repeated tendency not to take up offers of care such that it has a negative impact on the person and their life chances – is a major patient safety issue linked to high health needs and poor health outcomes. Research by the University of Glasgow has found that an average of two or more missed GP appointments per year was linked to a very high risk of premature death. In addition, those considered missing tend to have multi-morbidity and experience high socioeconomic disadvantage.

So what drives missingness? It can feel easy to attribute lack of engagement to chaotic personal lives and distrust of professional support – to assign blame. However, first and foremost, perceptions about healthcare are informed by experience and whether people feel that they are deserving of and will receive the care they need. Competing demands for a person’s time, the lack of opportunity to choose healthy options and difficulties reaching virtual and in-person healthcare add to this burden. And we cannot forget that fear, denial, stigma and shame often influence their decision-making.

From our side as professionals, we need to provide stable, consistent and caring relationships with the people we care for. Dr Carey Lunan, Chair of the Scottish Deep End Project, says these human connections work best when they are “sticky and inclusive”. Our services can only be sticky and inclusive if we act to make them accessible to all and particularly to “the missing”. We must offer careful and kind care that works alongside people’s lives, respecting the biography and circumstances that exist beyond care. To become responsive, wherever people seek help, we must take a “no wrong doors” approach and support people navigating our complex health and care system.

A note on continuity

Healthcare is not a series of interchangeable and faceless tasks. For many of us, the most fulfilling professional relationships are those we build with the people we care for over time. These deep interpersonal connections help us learn about them as people: their lives, their context and what matters most. It is no surprise to me that for those experiencing healthcare inequalities, relational continuity (seeing the same face) is important. And for those with the most complex health and social care needs, who may find it difficult to establish and maintain trust in our systems, continuity is all too often a missing element of care. When we get this form of relational care right, the people we care for face fewer hospital admissions, lower mortality and reduced use of wider services resulting in less waste.

Victor Montori talks about the privilege of the bedside: the awesome responsibility of trust we share when a person is at their most vulnerable. To enable sustainable and equitable care into the future, we need to strengthen this connection through continuity of care and recapture the privilege of looking beyond the bedside to see people as they want to be seen.

Vulnerabilities can be at their starkest as we approach the end of our lives. Most people prefer to die at home, and, in our culture, this is seen as an important aspect of a good death. However, people from the most socioeconomically deprived areas in the UK are less likely to die at home and more likely to die in hospital.

Late last year, I was moved by the Dying in the Margins exhibition – the culmination of a research study exploring experiences of home dying for people struggling to make ends meet. This is an area we don’t speak much about, but we should, because it’s not unusual. There were many powerful stories, but one that has stayed with me was Max’s story.

Max’s Story

Max (right) at home with his dog Lily, and his friend who was caring for him. Photograph © Margaret Mitchell

Max wanted to remain in his local community at the end of his life, to be with his friends, who were caring for him and his dog Lily. He was an army veteran with prior experience of homelessness and trauma and he felt trapped by institutions: “I prefer being at home. No one wants to be in a hospital.”

Each time Max’s symptoms became too severe, or his carers could no longer manage, he was admitted to a hospice. According to his friend and carer, at one point Max “did a runner from the hospice basically to get back to his dog.” He felt that the hospice environment was too restrictive. From then on, his care team took a trauma-informed approach to his care, which was more flexible and responsive to his needs. Max was able to be supported at home up until his final week.

Doing the right thing is at the core of Realistic Medicine – and takes on urgency as someone approaches the end of their life. Although Max’s story exposes the inequalities that exist in our society, I was moved by the care he received from friends and professionals alike.

Maximising Independence

The way we traditionally deliver health and social care isn’t keeping up with changes in the population and rising demand. By transforming the ways we work to reflect these changes, through careful and kind care and by practising Realistic Medicine, we will support people to live independently and achieve their full potential.

In striving for a sustainable system which supports people to live the lives they want to live, we must recognise that health and care professionals cannot provide all the answers, or services. But we can listen, act in partnership through honest and transparent conversation and understand the biography and biology of people and their communities.

As we grow older, social isolation and loneliness can affect our independence, along with increasing our risk of cardiovascular disease, physical frailty, cognitive decline and dementia. Taking Scotland to a place where individuals and communities develop meaningful relationships, regardless of age, status, circumstance, or identity, is desirable. That is why initiatives like The Knightswood Connects Project are so important, enabling and empowering people to rediscover human connection and helping them engage with society in a way that matters to them, Maximising Independence.

Social isolation in older men

Ann Harvey, Community Engagement and Activities Coordinator for the Knightswood Connects Project, maximises independence through her relentless commitment to achieving the best outcomes for older people.

Ann organises regular weekly activities such as art and exercise classes and health walks, short-term programmes and one-off events. I was struck by the human connection fostered in one of these short-term programmes – a six-week accessible golf course delivered in partnership with GP Link Worker Wullie Pearson from the Cairntoul Practice in Knightswood.

This programme was specifically aimed at men who might be more at risk of isolation and who could benefit from a bit of support to get out to play golf and meet new people. Six men who previously felt lonely and isolated built their confidence, developed skills and created a peer support group. This inclusive men’s group has gone from strength to strength, has doubled in size and the group are now attending weekly indoor bowling classes. Human connection matters and Ann’s passion for reconnecting isolated older people with their communities is inspiring.

Community initiatives like this teach us how to engage with the “missing”. For those who find that traditional means of accessing care challenging, embedding and co-locating services in communities is a very practical solution. I strongly advocate that we go to where the people we care for live their lives.

Across the country, care can be found in many guises. The Healing Arts Scotland network is an activation of health and arts organisations across Scotland. Their aim is to mobilise and strengthen local arts and health projects and organisations to help address health concerns, with a focus on loneliness and isolation, mental health in younger people, dementia and mental health in prisons.

Healing Arts Scotland 19-23 August 2024

Scottish Ballet are at the forefront of this exciting network and their Dance for Parkinson’s class is an excellent example of how the arts can contribute meaningfully to improve people’s experience of chronic disease whilst also improving social contact. This innovative class is part of a bespoke Dance Health programme of wellbeing support for people living with long-term health conditions, their carers and health professionals.

Parkinson’s disease causes movement problems such as tremor, stiffness and slowness. This class aimed to help people achieve the outcomes that matter - regain confidence, express themselves and build balance and fluidity of movement through structured and supported dance.

Care is a concept that goes far beyond the boundaries of healthcare alone. Our aim must be the enrichment of life if we are to improve health and wellbeing. It is a holistic response, social and cultural, that recognises individuality and serves to enhance the experience of life from the position and perspective of each individual. Care helps people to live and to fulfil their potential.

We must take time to properly understand the needs and wishes of the people and communities we serve; to see them in glorious high definition. We must work in partnership with them, meet them on their own terms and in their own spaces and empower them to get involved and support and care for each other. Not all suffering demands a healthcare response, and not all responses to suffering need to be professional. This perspective can promote more sustainable healthcare for fellow citizens of the communities in which we serve and help us reduce the impact of healthcare on our environment.

Contact

Email: realisticmedicine@gov.scot

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback