Realistic Medicine - Taking Care: Chief Medical Officer for Scotland annual report 2023 to 2024

This is the Chief Medical Officer Professor Sir Gregor Smith's fourth annual report, and the eighth report on Realistic Medicine. The overarching aim of Realistic Medicine is to deliver better value care for patients, and for our health and care system.

Chapter 4: Our Purpose: The Health of the Nation

“If we want a bright and sustainable future, we must invest in the building blocks of a healthy population and the mechanisms that safeguard our environment and wellbeing.”

Dr Fatim Lakha

Consultant in Public Health Medicine

Public Health Scotland and NHS Tayside

Health and wellbeing are fundamental to a flourishing society. However, after decades of improvement, Scotland’s health is now worsening. In Chapter One and Chapter Two, I shared some of the solutions addressing this issue. In this chapter, I will set out in depth the main factors driving inequalities in our society.

The Scottish Burden of Disease study predicts a 21% rise in reported cases of key diseases with cancers, cardiovascular disease and neurological conditions making up two-thirds of the projected increase. Many of these cases are preventable.

While NHS Scotland provides universal access to care it is not necessarily equal nor equitable. By “equal”, I mean giving the people we care for the same resources or opportunities while, by “equitable”, I mean going further to address the fact that some people or groups may need additional support, due to their circumstances, to get to the same place.

These challenges are deeply concerning but they are not insurmountable if we approach them resolutely and collectively, with empathy and action for those who experience inequality.

We know that most of the fundamental influences on changing health inequalities lie outside the health and social care systems. A wide range of factors impact the pursuit of a healthy life, and affect the underlying determinants of health, including food and nutrition, good housing, safe and healthy working conditions and a thriving natural environment.

To achieve a healthier, more equitable Scotland, greater focus should be placed on promoting good health and preventing health conditions from developing in the first place using the wider concept of care that we discussed in Chapter One. The pursuit of healthy ageing must begin at the earliest stages of life.

In the last two decades Scotland has implemented world-leading public health legislation, including smoke-free enclosed public places, smoke-free prisons and minimum unit pricing for alcohol. These policies are estimated to have saved lives, yet tackling health influencing behaviours alone is not sufficient to address the fundamental causes of inequality and poor health. We must address the wider determinants of health.

Life expectancy and mortality

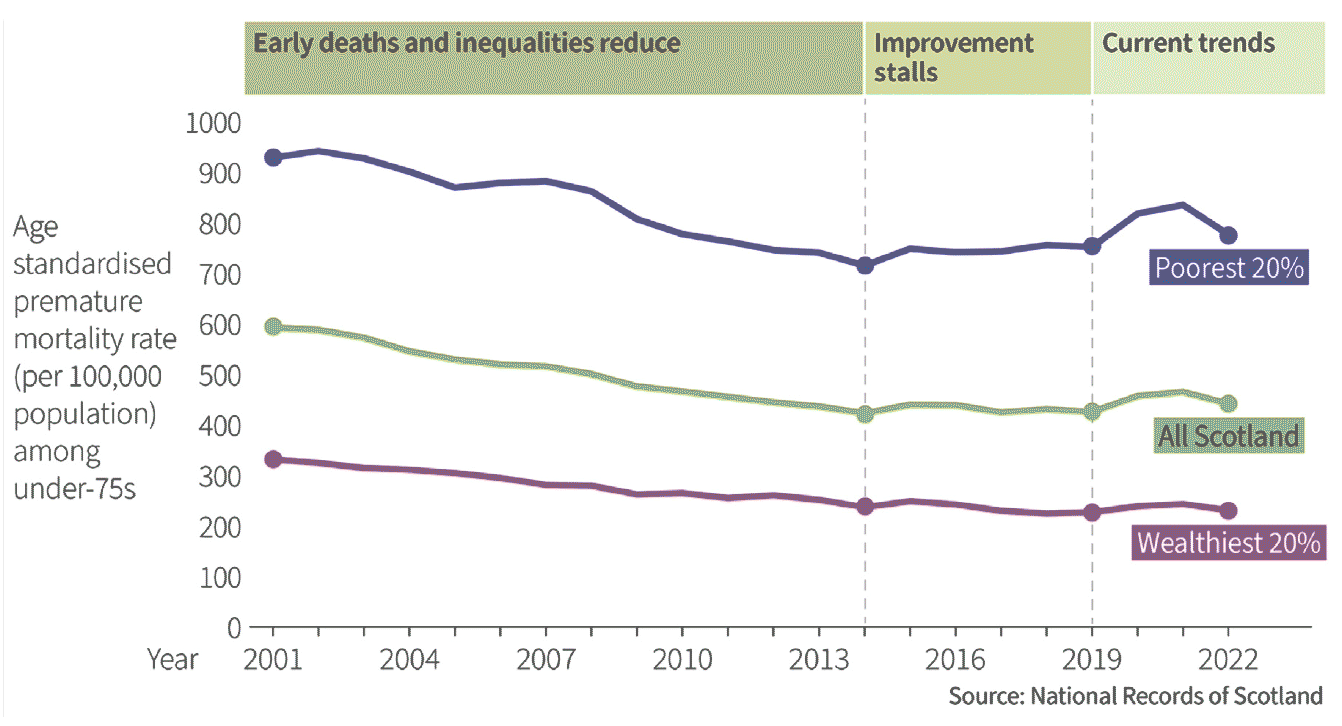

For many decades life expectancy in Scotland had been increasing, influenced by improvements in working and living conditions, changing habits and medical advances. However, since the early 2010’s Scotland’s health gains have stalled, and many measures of illness are now worsening.

There has been a change in the overall trend in life expectancy since the early 2010’s, and some segments of the population have fared worse than others. The difference in life expectancy between the most and least deprived areas narrowed during the 2000’s but then widened from 2011. This is because the least deprived areas have experienced a slowing in the rate of improvement while those living in the most deprived communities have experienced either a stalling (men) or a reversal (women) in improvement.

This change has happened in all parts of the UK. However, of the four UK nations, Scotland consistently has the lowest estimated life expectancy at birth for males and females – and is amongst the lowest in Western Europe. In 2020-22, life expectancy in Scotland overall was 76.5 years for males and 80.7 years for females.

Alongside these concerning trends in mortality and life expectancy, people are also spending more of their life in ill health, and again the impact is greatest in those living in the most deprived fifth of the population meaning that with increasing levels of deprivation, people are living a greater proportion of shorter lives in poor health.

Males living in our poorest areas live an average of 14 years less than males in the most affluent areas and experience poor health for 26 years longer, whilst for women it is 10 years and 25 years respectively.

On average, by the time people in our poorest communities have died, people in our most affluent communities are only just beginning to experience ill-health.

Ageing population

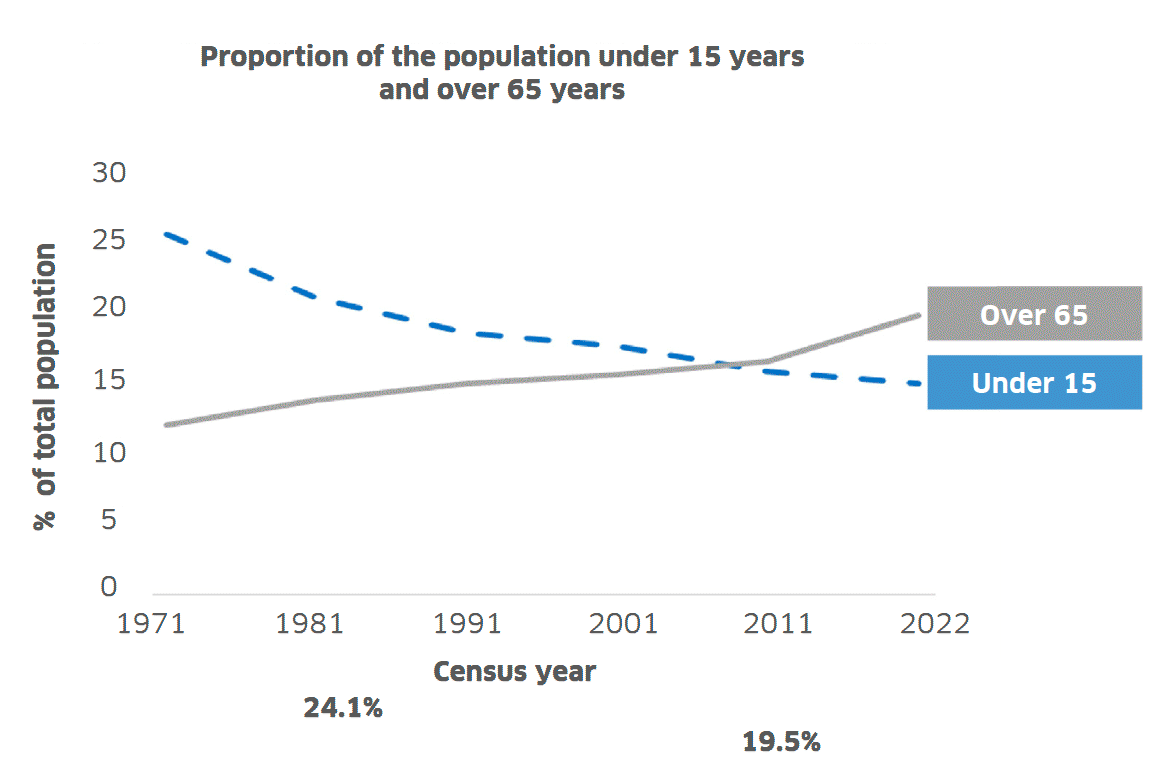

Although recent life expectancy has stalled, the proportion of older people is increasing whilst the proportion of younger people is decreasing. In 2011 the proportion of people aged 65 or over was similar to the proportion who were under 15 years – 17% and 16% respectively. By 2022 that had shifted, and 20% of people were aged 65 years or over, whilst those under the age of 15 had dropped to 15%.

Multimorbidity

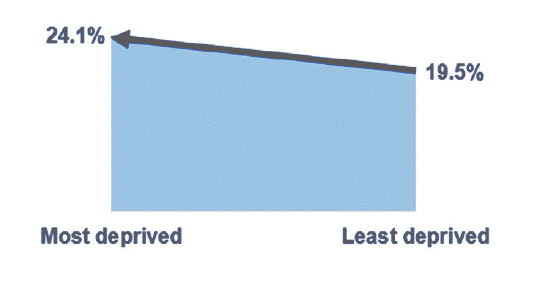

With older age there is an increasing likelihood of experiencing two or more long-term physical or mental health conditions. Multimorbidity is also socially patterned with a much higher prevalence in more deprived areas.

Overall, 1 in 4 people in Scotland live with two or more health conditions

Multimorbidity begins some 10-15 years earlier in the most deprived areas, compared with the least. It is associated with reduced physical and cognitive function, increased health and social care resource use and a higher risk of mortality.

There is some evidence that patients with multimorbidity experience gaps in continuity of care due to poor coordination across multiple health professionals and this can then widen inequalities further.

Disease conditions making the largest contribution to poor health and premature death in Scotland

International data shows that Scotland has a higher prevalence of largely preventable, non-communicable conditions, relative to comparable European countries.

When grouped together, the conditions which made the largest contribution to poor health and premature death in Scotland in 2019 were cancers, cardiovascular diseases, neurological disorders, mental health disorders and musculoskeletal disorders. These five grouped causes accounted for 63% of the burden of preventable disease in Scotland in 2019.

This burden is not borne equally across the population. The overall disease burden was double in the most deprived fifth of the population compared to the least deprived fifth.

Socioeconomic deprivation is a key driver of poorer health outcomes and over a third of health loss from early death and ill-heath is attributable to deprivation-based inequality.

In Scotland, 35 out of every 100 years of life lost to ill-health and early death are attributable to deprivation-based inequality. This is avoidable.

Mental wellbeing

A number of reports have highlighted the increasing trend in poor mental health and wellbeing of the children and young people of Scotland, including the Scottish Adolescent Lifestyle and Substance Use Survey (SALSUS).

The SALSUS indicates an increasing trend in poor mental wellbeing between 2013 and 2018 from 30% to 38% and it is likely that the prevalence of mental health problems has increased further during the COVID-19 pandemic. Anxiety and depression are among the leading causes of ill health and disability in adolescents.

Inequalities have a great impact on mental health, with associations between mental health and gender, age, ethnicity, social position, deprivation and being looked after/accommodated. Older adolescents (S4 pupils) have worse mental health than younger ones (S2 pupils) and girls, in particular, those at age 15, experience poorer mental health than boys.

Adolescents and young adults from the most socioeconomically deprived areas were twice as likely to die by suicide compared to the least deprived areas.

Prevention of mental health conditions and promotion of mental wellbeing need to start at the beginning of the life course as 50% of lifetime mental health problems start by the age of 14 and 75% by the mid-20s.

Poor mental health in childhood tracks into adulthood and can affect life chances, including academic attainment, employment opportunities and the formation of relationships further perpetuating inequalities. Adults who report four or more adverse experiences in childhood are more likely to report smoking, harmful drinking, obesity and cardiovascular disease.

This demonstrates the importance of actions to support parents, including prioritising adequate incomes for families with children, promoting parental mental health, addressing time poverty in family life and enabling nurturing caregiving, to create positive early life environments and experiences for all children.

Obesity

Whilst at the population level childhood obesity has remained at around 18%, this figure hides worrying trends within different socioeconomic groupings. The risk of obesity has been increasing in the most deprived areas and decreasing in the least deprived areas. By 2020, children living in the most deprived areas were twice as likely to have obesity compared to those in the least deprived areas.

However, whilst children living in deprived areas are at higher risk of obesity, overall levels of physical activity show that they are just as active as their more advantaged peers. This illustrates the negative consequences of other health-harming factors accumulated over the life course, including food insecurity, exposure to poor quality food, low quality green space, targeted advertising as well as time constraints and access to high quality preventative health services and treatment.

Around two thirds (67%) of all adults in Scotland are living outside of healthy weight parameters with rates in the most deprived areas persistently exceeding those in the least deprived. Of all health years lost in Scotland one in ten are attributable to excess weight.

The stigma associated with obesity exacerbates the difficulties associated with weight issues – both at an individual level in terms of discrimination and barriers to accessing support – and at societal level in terms of attitudes and responses.

Implications of poor health

Poor health has implications for individuals, communities, health systems, public services and the economy. There is rising illness among people in employment - from April 2023 to March 2024, an estimated 32.7% of those people aged 16-64 who were economically inactive was due to long-term sickness or disability.

More than a third of those aged 25-64 living in the most deprived areas are economically inactive due to long term sickness or disability.

This combination of increased illness burden and rising economic inactivity is having an impact on demand for, and staffing of, health and care services.

Where are we going?

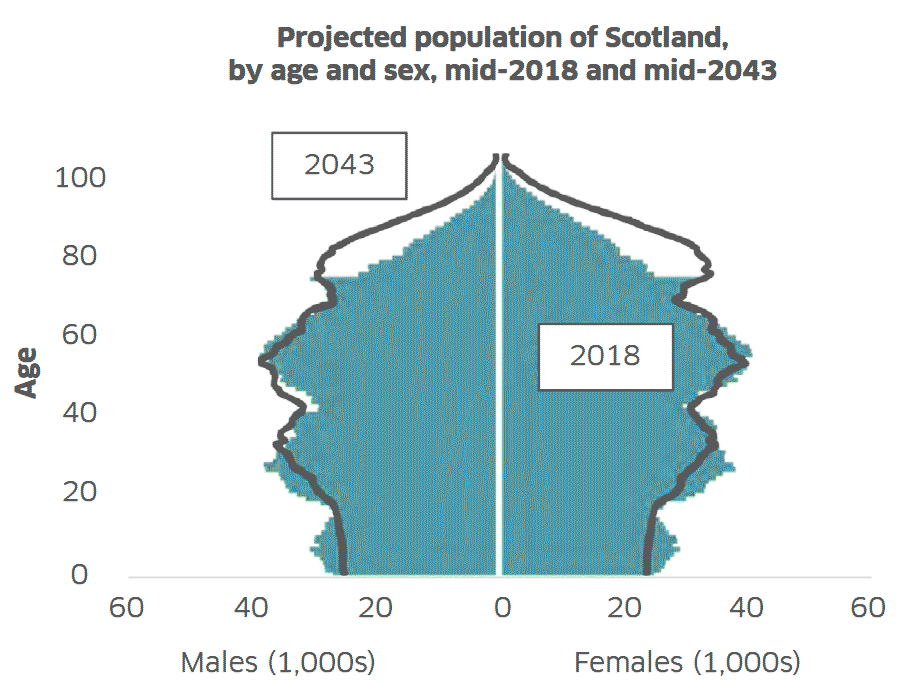

Over the next 20 years, the overall population is forecast to decrease by 1.2%.

However, because of population ageing, the overall amount of poor health and premature death experienced by the population is forecast to increase by 21% over the same period. This predicted increase assumes unchanged levels of morbidity and mortality at each age and is therefore based only on the changing age structure of the population. The largest absolute increases are forecast to be in those aged 65 and above, particularly those aged 65-84 years (35%). This highlights the importance of acting now to create environments that enable people to stay in good health for more of their lives.

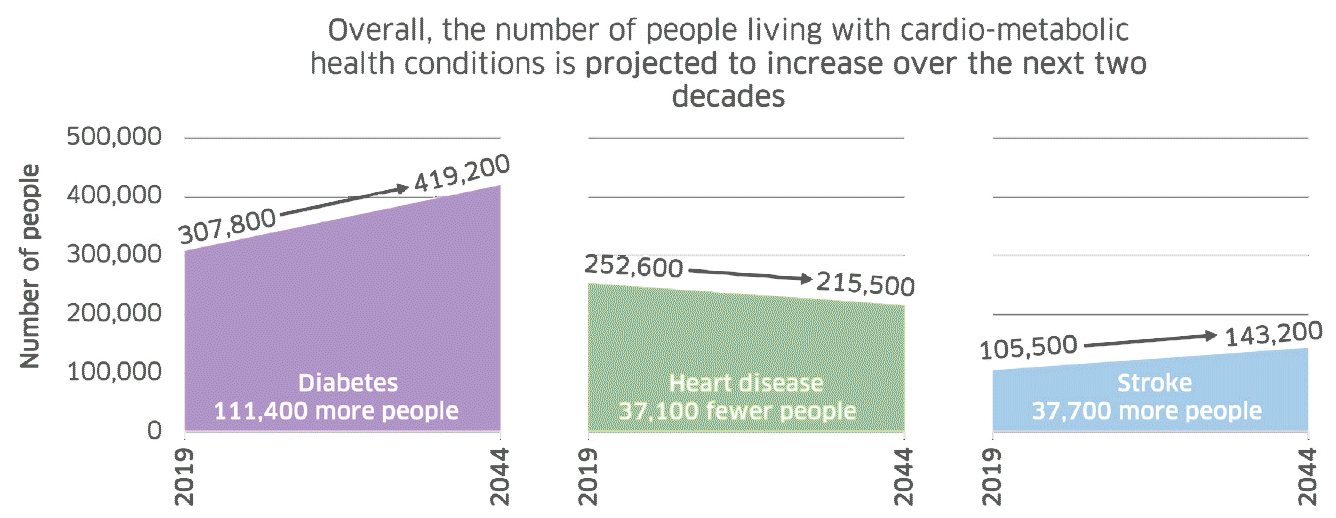

In considering the ageing of the Scottish population, and historical epidemiological trends, the number of people living with cardio-metabolic health conditions is projected to substantially increase over the next two decades. Much of these projected rises are attributed to the increased risks from ageing. These projections are sobering but they are not inevitable and we can change the course of this trajectory.

Increasing levels of poor health in the population will have an impact on the health and social care system. Much of the projected growth in illness relates to conditions which are predominantly managed in primary care and the community. Therefore the impact on these services is likely to be substantial.

Alongside this, the working age population (16-64 years) is estimated to decrease, meaning a smaller workforce overall. Again, this highlights the importance of acting now to create environments that enable people to stay in good health for a longer period of their lives.

What is driving the current direction of travel?

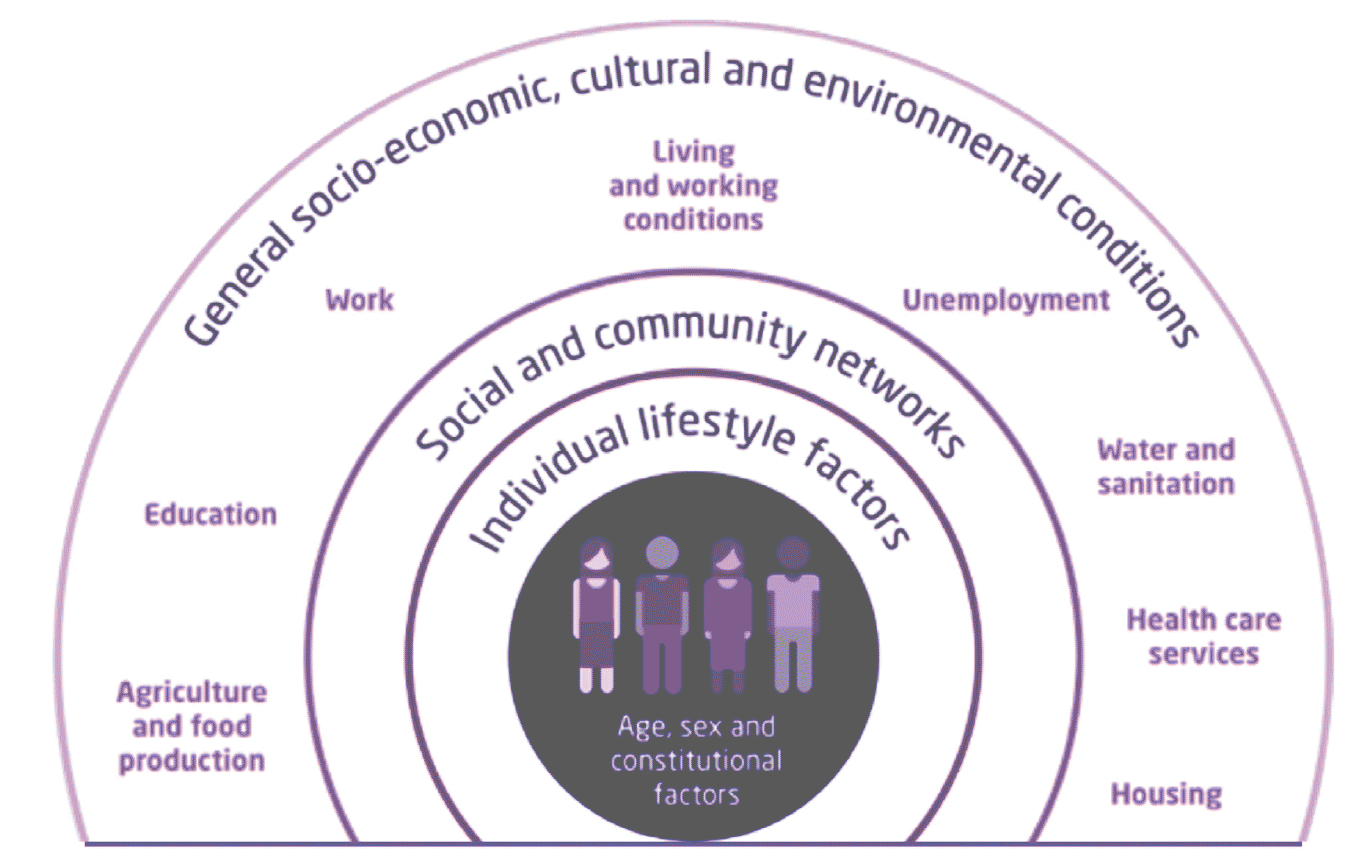

The population’s health is influenced by a complex interplay of various factors, often categorised into four broad categories: fundamental causes including social and economic factors, wider environmental influences like the food environment, individual experiences and access to healthcare services.

Factors influencing health, adapted from King’s Fund

Fundamental causes

Socioeconomic inequalities

The steep and increasing health inequalities reflect significant disparities in income, wealth and power in Scotland. Despite overall economic growth over the last decade, this has not been distributed equally. In 2018/20 the wealthiest 2% of households held 18% of all wealth. Wages have stagnated and in-work poverty has increased, so that 1 in 5 working age adults and 1 in 4 children now live in poverty.

This has been exacerbated by high inflation, causing adverse health impacts through food insecurity, fuel poverty, housing insecurity, transport poverty and reduced social support and interaction.

Marginalisation and discrimination – Intersectionality

The complex interaction between an individual’s characteristics, such as their ethnicity, disability, sexuality and religion, and existing societal structures can contribute to health disparities.

The importance of better understanding and addressing structural racism was brought to the fore when we saw its disproportionate impact on the health of people from minority ethnic groups during the COVID-19 pandemic. Alongside this it is key we also consider intersectionality, which is the complex, cumulative way in which effects of multiple forms of discrimination (such as racism, sexism and classism) combine or intersect to impact a person’s health.

Politics and legislation

After the financial crisis of 2008 a number of governments restricted growth in some classes of public expenditure, including public services and social security, as part of an ‘austerity’ approach that sought to restore fiscal balance after the large interventions made to prevent banks from failing. These policy decisions inevitably had a disproportionate effect on those on the lowest incomes and have been considered by a number of studies to have contributed to negative trends in mortality, life expectancy and healthy life expectancy.

Wider Environment

As we explored in Chapter One, a healthy diet and food environment are essential for supporting healthy growth and development in children. The wider environment, including commercial determinants of health, place and access to health services, also affect our health.

Commercial determinants of health

Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) are a leading cause of ill health and death in Scotland. Many of these are preventable. Harmful alcohol drinking, tobacco use, physical inactivity, and the consumption of unhealthy diets, particularly of ultra-processed food products, are the main risk factors for developing NCDs. Commercial determinants of health are strategies and approaches of the private sector that promote products and choices that are harmful to health.

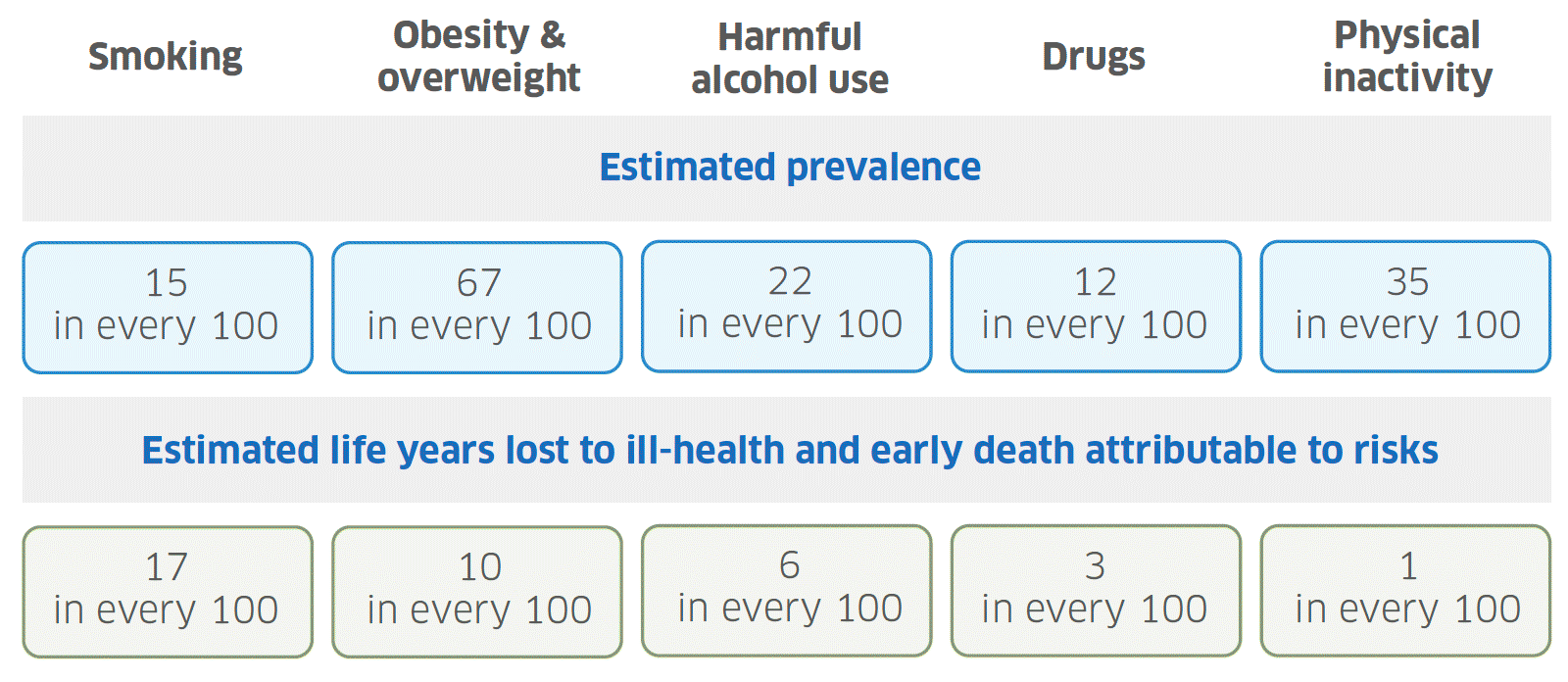

The prevalence of health-harming risks is high, leading to adverse impacts on the population’s health:

Graphic text below:

Smoking - 15 in every 100

Obesity & overweight - 67 in every 100

Harmful alcohol use - 22 in every 100

Drugs - 12 in every 100

Physical inactivity - 35 in every 100

Estimated life years lost to ill-health and early death attributable to risks

Smoking - 17 in every 100

Obesity & overweight - 10 in every 100

Harmful alcohol use - 6 in every 100

Drugs - 3 in every 100

Physical inactivity - 1 in every 100

Place – Movement, resources, space

The places in which people live, work and socialise also affect their health.

Low-income groups have less access to well-maintained parks or safe recreational facilities than those in higher income groups. Their neighbourhoods are more likely to lack features that support active travel and less likely to have access to supermarkets and places stocking healthy fresh food.

If we take the example of transport poverty, this impacts health in various ways. It can limit access to the building blocks of good health such as good work, training and education; it makes it difficult to access health and care services and it reduces the opportunity for community engagement.

Health and other services

Access to health and social care and the quality of these services is a significant determinant of health and tends to be worst for those who need it the most. This phenomenon is termed the ‘inverse care law’; people living in areas of higher deprivation, those from Black, Asian and minority ethnic communities and those from an inclusion health group, for example the homeless, are still most at risk of experiencing healthcare inequalities.

Addressing the causes of low engagement in healthcare, including missingness, is a prerequisite for reducing health inequalities and it is important to consider system factors as these have been found to have a stronger influence than patient factors.

What can we do about it?

Good health and ultimately how long we will live is shaped by a variety of interlinked factors: social and economic factors; health services; health behaviours; and the places we live and work.

Poverty, discrimination, poor-quality housing, low paid or unstable jobs all impact negatively on people’s physical and mental health. Education and skills, close relationships, productive employment, a benefits system that responds to need, debt support and legislation that makes it easier for people to avoid health harming exposures and activities: all have their part to play.

Tackling poverty, discrimination and addressing the widening inequalities in health we face as a nation will require cross-sectoral collective action and whole system working.

Support the building blocks of health

The largest drivers of population health are socioeconomic factors. Investing in building blocks like good quality education and employment, affordable housing, safe public and community transport, a benefits system that is responsive to need, debt support, youth services and community spaces designed with young people in mind, can create personal and community resilience. This will help keep people healthy and prevent increased pressure on health and care services in the future.

Public sector organisations, including the NHS, can commit to developing as anchor organisations, which I discussed in more detail in Chapter 2, and by adopting a Community Wealth Building approach to provide good quality employment, ensure investments maximise benefits for local communities, support inclusive enterprises, gain best use of land and property and recirculate wealth in local economies.

Adopt a health-in-all-policies approach across Scottish Government

Many of the drivers of poor health require action across Scottish Government and Community Planning partners. A health-in-all-policies approach means working to ensure policies across all sectors are designed to maximise benefits to health and prevent any risks to health.

This often involves completing a Health Impact Assessment (HIA), a structured process to assess the potential impacts of policy proposals. Public Health Scotland has a HIA Support Unit that is working to build capacity for HIA in Scotland.

Take a life course approach

Children have the right to enjoy good health. Children’s early experiences have an important effect on their long-term health and wellbeing. Positive early experiences are associated with better social and emotional development, better school performance, improved work outcomes, higher income and higher life expectancy.

On the other hand, adverse childhood experiences – including poverty/material deprivation, abuse or parental substance misuse, mental ill-health or imprisonment – are associated with poor long-term outcomes.

Children are not currently getting an equal start in life. Inequalities emerge early in life, in the prevalence of low birthweight, early child development concerns and risk of obesity at the start of school. Poverty and inequality constrain children’s access to the environments they need to thrive. Improvements are possible by investing in high quality support for parents from pregnancy through early years, primary school and beyond to deliver better outcomes in education, health, social behaviours and employment in the long term.

Create a health and care system focussed on equity, prevention and early intervention

To achieve the progress we want to see, greater focus will be required on promoting and maintaining good health and preventing health conditions from developing in the first place.

Embedding prevention is one of the most cost-effective interventions the public sector can make in relation to improving population health and reducing inequalities as well as delivering sustainable services.

Recent examples where action has been taken and made an impact include:

- HPV vaccine 89% reduction in pre-cancer cervical cell changes from 2008-2014.

- Childsmile Halved tooth decay amongst children between 2003 and 2020.

- Minimum Unit Pricing Estimated to have reduced alcohol hospital admissions (4.1%) and deaths (13.4%) from 2018-2020.

- Hep C prevention Will eliminate the hepatitis C virus by 2024.

- Smoking ban Reduced admissions for child asthma (18%) and heart attacks (17%).

- COVID-19 vaccines An estimated 22,138 lives were saved in Scotland by COVID-19 vaccines

The World Health Organization has compelling evidence that shows that investing in prevention promotes health and wellbeing and contributes to wider sustainability, with economic, social and environmental benefits. Examples where benefits are seen within just 1-2 years include mental health promotion, promoting physical activity, housing insulation and healthy employment.

Proportionate universalism and inclusion health

We need to ensure services are designed, delivered and prioritised to have maximum impact on health inequalities given the observed trajectory of health outcomes in Scotland. This requires applying a human rights-based approach to healthcare so everyone experiences fairness, respect, equality, dignity and autonomy and resourcing across the country according to need.

A recent example of an initiative which is taking both approaches is the Inclusion Health Action in General Practice project. This has provided additional funding to GP practices with high concentrations of patients from the most socioeconomically deprived areas in Greater Glasgow and Clyde to address some of the barriers to providing high quality, accessible, care to those who need it the most.

Themes within the project cover proactive outreach to those patients identified as being a high risk through missing multiple appointments, extended consultations to address the high levels of multimorbidity within the most socioeconomically deprived populations, building community voice to allow co-production of services to meet the needs of the population and staff training on inclusion health topics to facilitate this.

Contact

Email: realisticmedicine@gov.scot

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback