Recovery Housing in Scotland: Mapping and capacity survey of providers 2022/23

This report provides the findings of a mapping and capacity survey of recovery housing facilities for drug and alcohol use in Scotland.

3. Findings

The survey received 19 responses. Five providers identified through the scoping exercise responded to specifically say they did not consider themselves to be a recovery house[5]. A further 23 of the 43 potential recovery houses did not respond. As such, the research presented may not have captured the totality of recovery housing services available to people in Scotland.

Three invalid responses were removed and a duplicate response consolidated, resulting in a total of 14 responses for analysis (see Appendix B). One of these facilities[6] was identified in a previous mapping survey of residential rehabilitation facilities in Scotland published in 2020. However, that report highlighted that the distinction between residential rehabilitation services and specialised supported accommodation services was, at times, ill-defined. Specifically, four of the residential rehab services offered “specialised supported accommodation services”, which may be a form of recovery housing (see Appendix B). The decision was made to include this service in this report based on the content of their response to the survey of recovery housing facilities and how this aligned with the recent review of the literature.

Two of the 14 responses were from facilities based in England. One of these responses was incomplete and due to issues around base numbers and risks around identification, these findings could not be reported on. However, the partial information provided in these responses indicate that these providers are broadly in line with those in Scotland in terms of the service they provide. Although they would in principle accept applications from people in Scotland, these were reported to only make up a small percentage of their past or current residents.

The remaining 12 responses were from facilities based in Scotland and are included in the analysis presented in this report.

3.1 Profile of providers

3.1.1 Location

The providers are based in four different ADP areas (Edinburgh City, Glasgow City, Highlands and West Dunbartonshire), and describe having a range of single, double or multiple occupancy flats or houses spread across these areas.

3.1.2 Workforce

A range of workforce sizes and job roles were described by respondents. All but one employ staff in a paid capacity, although the composition of this workforce in terms of job roles varied considerably across providers. All of these providers employ support workers; most listed administrative staff including finance officers; some also mentioned house managers (including deputy managers, operations managers and project coordinators) and project worker/service leader/team leaders; a couple mentioned addiction workers or recovery coaches and clinical roles, (e.g. clinical nurse manager). In addition, the majority of the providers reported having unpaid staff or volunteers in roles that included peer mentors, students on placement, support staff and house warden.

Of those who responded (n=11), all reported that there is some level of lived experience involvement within the running of their service. About half explicitly stated that both their paid and unpaid workforce have lived experience of problem substance use, with one provider specifying that over half of their staff had previously been residents. Less commonly, providers reported having resident-level involvement in the running of the service. For example, with residents involved in staff interviews and participating in expert panels to shape the development of the service.

3.1.3 Funding and accreditation

All but one (n=11) of the providers are third sector organisations, and one is statutory funded.

Most providers who provided information on their funding (n=9) reported having several streams to support their service. The most commonly mentioned source of funding was housing benefits. Other sources included the local council or ADP, private trusts and grant funders or private donors, the NHS and the Church of Scotland. Only one provider who responded to this question described themselves as self-funded.

All providers expect residents to make a financial contribution towards their living costs (e.g. groceries, bills, rent), although they described different arrangements and amounts. Responses were fairly evenly divided between two approaches. In the first, residents are responsible for covering the totality of their living costs, although a few mentioned that some of this (e.g. rent) is covered by housing benefits that residents receive. One of the providers specified that residents are offered support to manage their budget. In the second, residents are required to contribute a weekly or monthly payment towards their living expenses. Where specified, these payments ranged from around £7 to £30 a week.

Of those who provided a response, the majority of providers (n=9) are registered with the Care Inspectorate. Three providers stated that their staff are also registered with the Scottish Social Services Council. Other registrations/accreditations include the NHS[7] (n=1).

3.2 Capacity

Providers reported a combined total maximum capacity of 235 places at 84% full capacity at the time of the survey, with 197 of these 235 places being filled. The size and structure of the recovery housing providers and their facilities varied considerably. The largest provider had capacity for 79 residents, making up a third of the total places across Scotland. However, most providers had capacity for much smaller numbers of residents; over half of the providers (n=6) had capacity for between 5 and 11 residents and the rest (n=5) for between 16 and 35 residents.

Providers reported offering a variety of types of accommodation. Around half of the providers (n=6) offer only shared-living housing, from two-bed to 16-bed flats or houses. Three providers offer only single-occupancy flats. Three providers offer a combination of both single-occupancy and shared living accommodation.

3.3 Referral pathways

Referrals are made by a range of organisations but most often come from residential rehabilitation providers (n=9) and drug and alcohol services (n=8). Referrals from ADPs (n=5), local authorities (n=5) and prisons (n=5) were also fairly common. Residents tend not to self-refer, with half of the providers (n=6) reporting that this is never the case.

Residents most commonly come from the provider’s local ADP or NHS health board area (n=11). Over a third of the providers (n=5) had only received residents from these areas, while the others reported sometimes accepting residents from the rest of Scotland or, more rarely, the rest of the UK.

Providers use a range of means to publicise their service. All reported using online platforms (e.g. websites or social media) and other routes included paper-based promotion materials such as leaflets and posters (n=8) or promoting at in-person events (n=4). Only two providers specified that promotion was not relevant to their service, as their referrals were from a single established pathway.

3.4 Admission criteria and process

3.4.1 Resident demographics

Most providers accept both men and women (n=8), while three are limited to men only and one to women only. All providers cater for adults and most accept a wide range of ages to their facility. All cater for adults aged between 26 and 64, most (n=9) also accept people from the age of 18, and five providers cater for older adults (aged 65+). None cater directly for children (under 18 years old), although, as discussed below, some can accommodate residents with dependent children.

The focus of most providers (n=8) is on supporting people with both problem alcohol and problem drug use. While the remaining providers responded that their primary focus was on homelessness (or in one case, mental health), they also reported that their residents are often in recovery from a range of substance use profiles.

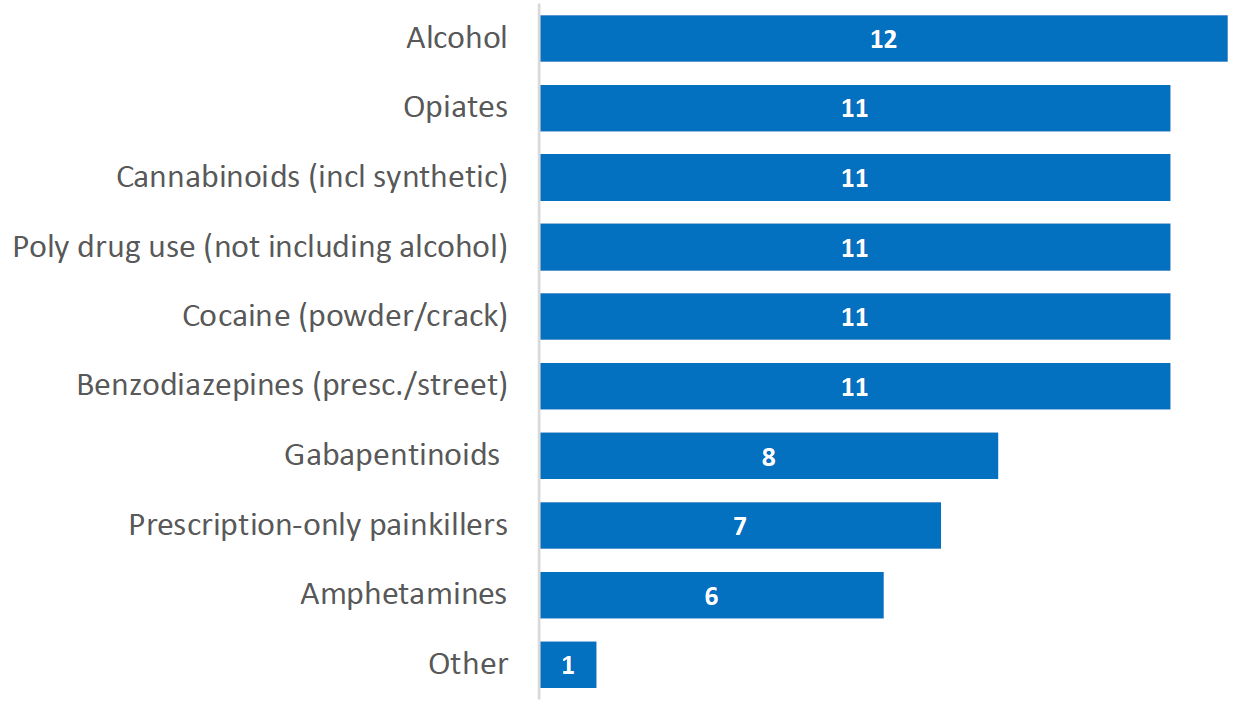

Respondents reported a range of substances previously used by their residents , the most common of which were alcohol, opiates, cannabinoids, cocaine, or benzodiazepines (See Figure 1). Being in recovery from polydrug use (not including alcohol) was also reported to be common (n=11), with one provider unsure of its prevalence. Other substances reported were etizolam and “legal highs”[8].

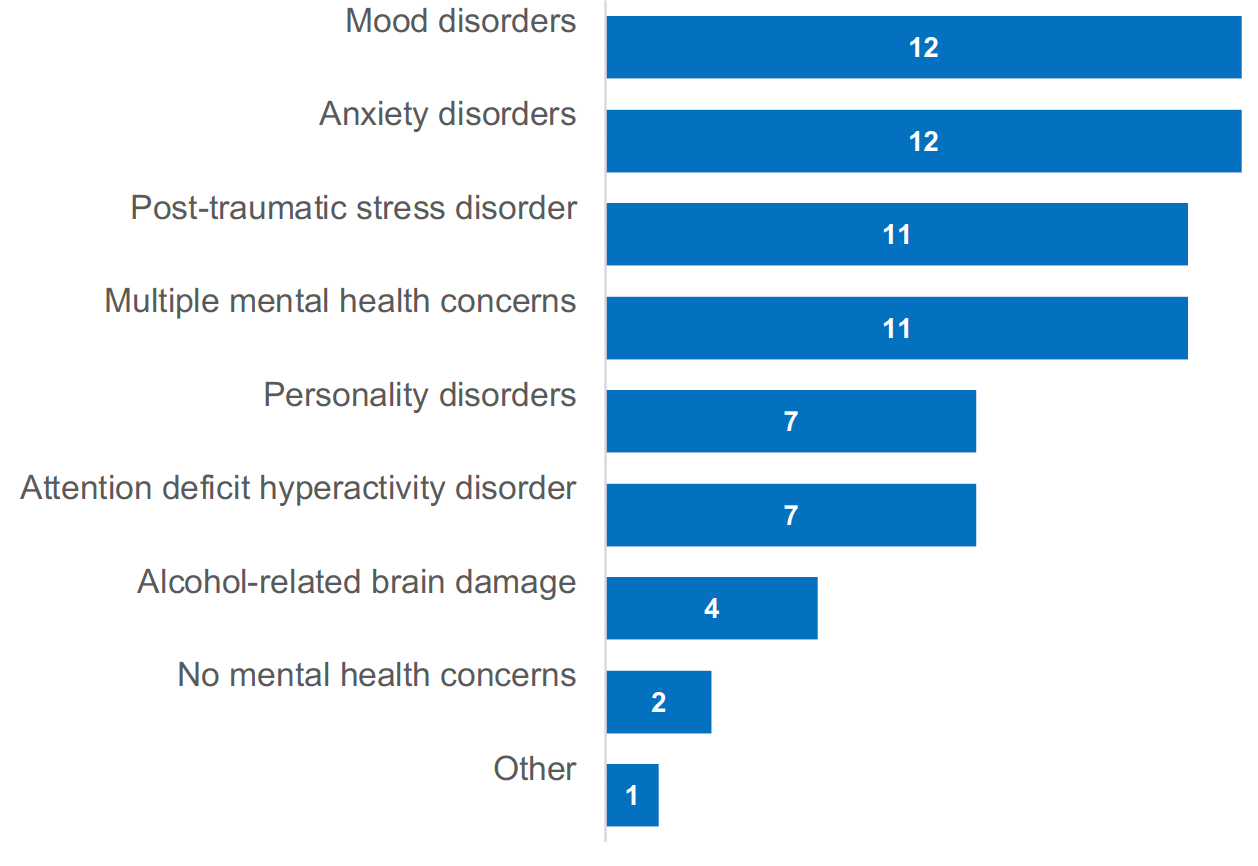

Respondents reported being able to support a variety of needs. All reported accommodating people who had experienced homelessness and most support people who had formerly been in prison (n=10). Most also support people with specific mental health concerns (n=10) and reported a range of mental health concerns among their residents (See Figure 2). Most respondents (n=9) reported that it is rarely or never the case that residents present without one. It is common for people to have multiple mental health concerns (n=11), with respondents all reporting that anxiety and mood disorders are most often observed. One respondent also reported that psychosis is common in their residents.

Other groups that providers were able to cater for included people from the LGBTI community (n=8), people from different religious backgrounds (n=8), people with a physical disability (n=7) or a learning disability (n=6), and people from the Traveller community (n=6). Notably, fewer respondents reported being able to support specific demographic groups such as women who are pregnant (n=3) or with dependent children (n=2), and men with dependent children (n=2).

Specific measures taken to accommodate different demographics included adopting a person-centred approach to meet needs; providing women with separate accommodation from men; engaging interpreters; arranging specific needs assessments and referrals; and accompanying people to appointments.

3.4.2 Individual-level entry requirements

All providers reported having specific entry criteria for residents, with the majority citing the need for evidence of motivation toward recovery (n=9). Other common entry requirements are:

- Completion of a residential rehabilitation programme (n=6)

- Period of abstinence prior to admission (n=6)

- No/limited use of non-prescribed medication (n=5)

- Homelessness status or risk of homelessness[9] (n=5)

- No history of specific offences (e.g. arson, violence crime) (n=4)

- Stable on Opioid Substitution Therapy (OST) (n=3)

- Stable on prescribed medication (excluding OST) (n=3)

- Evidence of a plan in place for future accommodation (n=2)

- Has support network of family and friends (n=2)

- Extended period (years) of problem substance use (n=1)

- ‘Other’ criteria mentioned included already being engaged in their recovery programme, eligibility for housing benefits, and the current profile of other residents at the time of entry.

3.4.3 Process for assessing applications

Most of the providers reported that paid service staff (e.g. support workers, house managers, pre-admission officers, housing officers) are involved in assessing and responding to applications. Some providers also noted that the local authority is involved in assessing applications. None of the respondents described current residents being involved in screening and responding to applications.

Over half of the providers (n=6) reported that they had declined between one and two applications in the last month, while over a third of services (n=4) had not declined any. The most common reason for declining applications cited was entry requirements not being met. Other reasons mentioned were that the service could not accommodate the accessibility needs of the applicant and a lack of capacity at the time of application.

3.4.4 Waiting list and waiting times

The majority of the providers (n=8) did not have a waiting list at the time of the survey, and most described operating on a first come-first served basis or based on an assessment of priority needs. The four providers who reported having a waiting list cited waiting times that could vary considerably from weeks to months. Two of these providers reported that people often dropped off the waiting list during this period for reasons such as experiencing a relapse or finding accommodation at another service.

3.5 Service offered and approach to recovery housing

Despite being commonly used in the literature, ‘recovery housing’ was not a term that most respondents felt best described their service. While five respondents felt this was one of several terms that could describe their service (others included ‘dry house’ and ‘sober living house’), most (n=7) agreed that their service could be described as ‘supported accommodation’. This is in line with a review of the literature that found that a lack of clarity in the terminology used to describe and differentiate between the various models that fall under the umbrella term of ‘recovery housing’.

However, when asked to describe their service, respondents often referred to key aspects of recovery housing as it is outlined in the literature: an abstinence-based and supportive environment in which people were provided somewhere to live while receiving varying types of ‘professional’, ‘personalised’ or ‘holistic’ support to transition into healthy independent living.

Additionally, when asked to what extent they agreed with several statements about recovery housing drawn from a review of the international literature on recovery housing, there was a strong consensus of agreement with all the statements[10]. This suggests that while there may be different levels of awareness of the term “recovery housing” and variations in how the providers operate, they share a common ethos that resonates with how recovery housing is described in the literature.[11]

Recovery housing models adopted in Scotland are not directly comparable to what is described in the international literature. The survey included several questions aimed at assessing whether recovery housing providers in Scotland mapped onto the levels of recovery housing identified in a review of the international (but primarily US-based) literature. Analysis of the responses to these questions indicated that, while there are some similarities with aspects of the recovery housing model described in the review, this cannot be said to clearly map onto how recovery housing operates in a Scottish context.

In Scotland, providers can broadly be described based on whether accommodation is shared with other people in recovery or not. About two thirds (62%, 146 out of 235 places) of the available recovery housing capacity in Scotland is provided in the form of single occupancy flats. The majority of these places are offered by three providers. While the majority of providers (n=9) offered some form of shared accommodation, this was most commonly for small numbers of people (2 or 3 residents per flat). Only three providers catered for larger numbers (between 5 and 16 people) and they tended to provide more structured support within the house to their residents than the other providers. However, further research is required to better understand how these two categories of recovery housing providers may differ in the service they deliver, and in the outcomes they achieve for their residents.

3.5.1 Treatment and support offered

The majority of respondents (n=10) reported following a specific model for recovery from substance use. These included a faith-based model of recovery (n=3), one based on the principles of the 12-Step model (n=3) or therapeutic community model (n=4).

A range of treatment is made available to residents, either by the provider or through facilitated access to relevant services, with only two providers reporting that they do not offer or actively facilitate specific treatment. Treatments listed included counselling/ group therapy and recovery groups (both on and off site) as well as access to recovery support groups (e.g. alcoholics anonymous, narcotics anonymous), faith-based programmes, recovery cafes, local hubs and abstinent day programmes. One provider mentioned a 14-week residential rehabilitation treatment programme, which is available to the residents before joining the recovery house. Three providers provided detail on their group programmes. Two facilities discussed a 15-week group recovery programmes that is delivered in-house. This programme covers recovery; emotions and feelings; and developing skills. Another provider described ‘intensive’ group work that tackles diverse topics relevant to recovery, including offending, health and wellbeing, relationships, finance, housing, and meaningful activities.

Recovery housing providers also offer or support access to range of specific activities (e.g. house meetings, one-to-one support, life skills training, mutual aid, peer/mutual support groups and exercise classes) and harm-reduction interventions (e.g. provision of naloxone, blood-borne virus screening and overdose prevention support), either within the accommodation or by facilitating access to relevant services.

Most providers (n=9) have no requirements for their residents to work, study, train, or volunteer. The reliance on residents’ housing benefits may be a barrier to pursuing work while living in recovery housing, with a few providers highlighting that due to the benefit’s requirements only allows for part-time employment. Only two providers require residents to pursue either work or some form of learning, either by participating in the facility or engaging in a certain number of hours of meaningful activities. However, most providers encourage and support what residents want to achieve by facilitating access to external education, training/apprenticeships and employability support services, although some provided this support in-house.

3.5.2 Duration of stay

Most providers reported that residents stayed an average of between 12 and 18 months. Three providers reported an average stay of around 2-years, with one specifying this is because residents have to wait for social housing to become available. Most also did not operate with an upper limit on duration of stay. Where a limit on duration was set, this ranged between one and three years.

3.5.3 Governance and house rules

Providers reported a range of governance arrangements, ranging from staff entirely running the service (either with or without resident involvement) to providing support to residents. None described a service entirely run by residents.

Most providers (n=10) require their residents to abstain from using alcohol and/or drugs. One of the two providers that did not reported a focus on tackling homelessness and disagreed with the statement that recovery housing generally refers to substance-free living environments. The other provider strongly agreed with this statement[12].

Of those that required abstinence, all but one (n=9) said that they actively monitored this through conducting drug/alcohol tests either randomly or if substance use was suspected.

Residents are not commonly evicted in the event of a relapse. Instead, most providers (n=11) described dealing with these instances on a case-by-case basis to determine what support could be provided to the resident to enable them to remain and maintain abstinence. Some described notice periods during which support was provided but should the resident be unable to maintain abstinence, would lead to eviction.

In addition to abstinence, providers described a range of core rules and expectations that their residents are expected to adhere to. Most commonly, this included restrictions on overnight guests, keeping the accommodation clean and tidy and adhering to a curfew. Less commonly reported rules and expectations included: adhering to the tenancy agreement, zero tolerance to violence, respecting other residents, attending support, staying for at least 5 nights, undertaking drug/alcohol tests on request, no children on-site, and no visitors under the influence of substances. Failure to adhere to the rules was cited as possible grounds for eviction, alongside others such as violence, engaging in criminal activity, and non-payment.

The majority of providers (n=7) allow current residents to set or amend house rules by following different types of processes including an open-door policy for ideas and amendments to rules, house meetings, house rules reviews meetings with residents, or a suggestion box.

3.6 Resident outcomes and next steps

Providers reported a range of ways used to monitor resident outcomes. Tools mentioned included Outcome Star and a separate outcome web matrix to monitor progress in different areas of recovery. Other approaches included exit evaluations, support/care plan reviews, risk assessments, gathering feedback from family and residents, and working with other agencies.

Over a third of providers (n=5) have no formal aftercare plans, however most providers offer some form of continued contact to residents once they leave. The type of support and formality of the arrangements vary across providers and ranges from adopting an open-door policy where ex-residents are welcome to get back in touch if they feel the need for light-touch support (e.g. sign-posting, help with forms), to more structured formal arrangements that included weekly or monthly meetings with a support worker, or following-up at the six-monthly or yearly mark following departure.

Residents most commonly move on to housing association accommodation and council accommodation following a stay in recovery housing. Less common types of accommodation included private tenancies or ownership, returning home, the provider’s own move-on/scatter flats and moving in with family. Most providers reported that residents rarely if ever choose to move to another form of recovery housing during or after their stay.

Residents rarely go to residential rehabilitation during or after their stay in recovery housing. Most providers noted that this is because residents often come to them following completion of a residential rehabilitation programme. One provider noted that residential rehabilitation could be an option in the case of a relapse during the stay in recovery housing.

3.7 Improvements to recovery housing services

Respondents made a number of suggestions for improvement:

- More and better funded recovery housing facilities. One of these responses highlighted the importance of being able to access recovery housing following completion of a residential rehabilitation programme to support people to transition back into the community. They argued that without safe and stable housing at this early stage of recovery, people are being “set […] up to fail” as the alternative is often to return to homes and environments where they had historically been using substances.

- Recovery houses that incorporate different stages of housing (with varying degrees of structure and support) to support the transition to independent living are needed. This was argued to be a more inclusive model of recovery housing and provides more options to individuals at all levels of recovery. Increased funding for other aspects of recovery housing, including: to increase recovery house staffing; more care funding for clients to be referred; and investment in meaningful activities to give residents purpose and direction, as boredom and isolation are leading drivers of relapse.

- Increased linkages between recovery housing providers and other recovery services, including: better therapeutic employment links; having a wide range of community peer and professional support; better access to professional counselling and mental health support ; and more informed aftercare provisions once residential rehabilitation is completed that can link to recovery housing.

- One provider raised the importance of meaningful co-production in developing recovery housing. They asked for increased engagement of individuals who have lived in and worked in recovery housing in recovery housing matters.

Contact

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback