Repeat violence in Scotland: a qualitative approach

This report presents findings from a qualitative research study which explored peoples’ experiences of repeat, interpersonal violence. The research involved in-depth interviews with people who have lived experience of repeat violence and community stakeholders who support them.

2. Research design

Overview

This chapter describes the research design, which involved qualitative interviews with people who have lived experience of repeat violence and a range of stakeholders who support them. Data collection was conducted in six case study areas: two Urban, two Town and two Rural communities characterised by high levels of deprivation and violent victimisation. The discussion which follows sets out the rationale for this approach, as well as outlining key issues relating to sampling, limitations, and ethics.

Aims and objectives

The aims of developing the evidence base on RVV set out in the research specification were as follows:

(i) To help improve support for victims in Scotland, by providing evidence on the support needs and experiences of those who are victims of the most hidden and stigmatised forms of violence, and who therefore tend to be less likely to seek and access services.

(ii) To inform policy decisions to prevent and reduce violent offending in Scotland, particularly by developing an understanding of the relationship between RVV and violent offending in adults.

(iii) To contribute to the development of policing strategies in Scotland, by providing data on the factors that increase vulnerability to repeat victimisation amongst high-risk groups.

These aims were to be achieved through the following empirical objectives:

- Exploring the characteristics and contexts/circumstances of those who experience interpersonal RVV, including people with particular equalities characteristics, people who live in deprived communities, people with convictions, and people with multiple complex needs.

- Examining victim-survivors' understandings and experiences of RVV, focusing on the nature, context, and timing of RVV (exploring its relationship to other forms of victimisation and/or offending, alongside intersecting forms of vulnerability and harm).

- Assessing the impact of RVV on victim-survivors, e.g., in relation to health and wellbeing, relationships and social inclusion/exclusion; and

- Considering victims' experiences of seeking help and support, including barriers to access and views on which forms of support would be most helpful in future.

Whilst the study focused primarily on non-sexual physical violence against an individual person, the original research specification acknowledged the need to attend to the relationship between physical and other types of violence, as well as other crimes, as these arose during the fieldwork. The specification also acknowledged that many victims of violence do not consider themselves to be 'victims' or want to be identified as such.

Research questions

The aims and objectives set out above were examined through the following research questions:

1. What are the characteristics and circumstances/contexts of people who experience interpersonal RVV?

2. What are victim-survivors' understandings and experiences of RVV?

3. What impact does interpersonal RVV have on victim-survivors?

4. What are victim-survivors' experiences of seeking help and support with RVV?

Research design

Fieldwork took place over 12 months, focusing principally on in-depth, qualitative interviews with people with direct experience of repeat violence (n=62), alongside shorter, semi-structured interviews with community stakeholders (n=33). To provide important contextual data on communities and services, this primary data collection was centred in distinct, geographically defined communities: Urban, Town and Rural areas characterised by high levels of deprivation and violent victimisation.

Stage 1: Selection of case-study areas

The initial stage of the study required research site selection. We took careful steps to ensure that areas were selected based on available data, to avoid over-researching certain areas or stigmatising communities. With assistance from Scottish Government analysts, we cross-referenced the latest recorded crime statistics against the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation (SIMD) and isolated areas with high levels of violent crime which were within the bottom 15% of SIMD data zones at council ward level. We took the pragmatic decision to amalgamate multiple contiguous areas from the list of council wards that met the inclusion criteria so that the case study areas could be embedded in and reflect communities as they were more broadly understood by local community members. We then mapped these areas against the six-point Urban-Rural classification system (Scottish Government, 2020) which resulted in a series of potential case study areas marked as (large) Urban, (urban) Town and Rural.

During the early project inception and re-planning stages of the study, we agreed with the Scottish Government Project Manager and Research Advisory Group members that while a rural perspective was important to the research it would be both pragmatically and ethically challenging to focus on one rural location and, instead, it would be appropriate to explore any area considered 'rural' and with higher levels of deprivation. This included areas which are accessible, remote, or very remote in line with the Scottish Government's (2020) Urban Rural Classification scheme. Various rural communities were consulted throughout the fieldwork, but these have been clustered into two categories – West Rural and East Rural – to avoid identification of participants.

In Stage 1 of the study, we focused on case study areas in the West of Scotland, to mitigate the risk of localised COVID-19 restrictions on our ability to conduct fieldwork. In Stage 2 of the study, we included additional East of Scotland case study areas.

While these various case study areas had traits that were comparable to other communities in Scotland, given the qualitative nature of the inquiry the findings of the research should not be read as a representative picture of repeat violence in Scotland (see Sampling, below, for further discussion).

Stage 2: Stakeholder interviews

Stage 2 of the study involved identifying appropriate access points and potential participants. We made connections with a range of local and national 'stakeholder' organisations that support people with lived experience of repeat violence and asked if they would be willing to take part in the research. Organisations were initially contacted by e-mail and the aims of the study were explained. This was followed up by a face-to-face or online meeting with relevant staff who were invited to take part in an interview and share information about the project with the people they support.

An overview of completed stakeholder interviews is provided in Table 1. The majority of these were conducted in our initial Urban, Town and Rural case study areas, although we also spoke to relevant stakeholders from outwith these areas including representatives from national organisations.

| Study area |

Statutory |

Third sector |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| (Large) Urban |

3 |

9 |

12 |

| (Urban) Town |

4 |

3 |

7 |

| Rural |

4 |

5 |

9 |

| Other |

1 |

4 |

5 |

| Total |

12 |

21 |

33 |

We exceeded our initial target of 20 stakeholder interviews, completing 33 interviews with youth workers, police officers, social workers, community development workers as well as support workers based in prison throughcare, homelessness, housing, addiction, and specialist victim services. The interviews were semi-structured in nature and followed a topic guide covering stakeholders' understanding of the nature, context and circumstances surrounding repeat violence within their relevant communities; its impact on victims; as well as their views on existing service provision and barriers to accessing support.

Interviews took place between May 2022 and February 2023, and, with explicit permission from participants, we audio-recorded interviews using external and encrypted dictaphone devices. Participants were all given the choice of completing interviews face-to-face, on the telephone, or via their preferred remote video conferencing platform; 18 opted to meet in person and 15 preferred to meet remotely via MS Teams. In-person interviews took place in a private office or meeting space, usually in stakeholders' workplaces or community hubs, aside from one which took place in a public park due to post-pandemic workspace sharing restrictions. The average length of stakeholder interviews was 62 minutes; they ranged between 40-120 minutes in length and amounted to almost 31 hours of recorded interview data.

At the end of each interview, we agreed on a 'generic' job title with stakeholder participants to help provide context about their roles and their sector without identifying them. We opted to use job titles that reflected the broader role, e.g., 'social worker', 'police officer', or 'community development worker', rather than providing further information about specialism. We adopted a tiered approach to de-identifying organisations represented by stakeholders to reflect the operational structure and scale of the organisation without compromising our confidentiality assurances. For example, it was impossible to de-identify certain organisations such as the police or local authorities. Although some grassroots and community-based organisations expressed a desire to be identified through the research to highlight the outreach and scope of their support provisions, there were ethical concerns about participants with lived experience being identifiable – and so these organisations are not named in the report. Some of the national organisations offering support to victims are identified, given the larger scale of their operations.

Stage 3: Lived experience interviews

Stage 3 of the study involved in-depth qualitative interviews with people with lived and living experience of repeat violence. In the main, participants were accessed via third-sector organisations that participated in stakeholder interviews; however, in two of the case-study sites we employed lived-experience research assistants to assist in recruitment and interviewing as a means of reaching individuals who were not accessing services and who might not usually participate in academic research. We also advertised the study via social media and a dedicated project website and distributed posters within public spaces in our case study communities.

In total we interviewed 62 people with lived experience of repeat violence, just exceeding our target of 60 participants. An overview of these participants is provided in Table 2.

| Study area |

West |

East |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| (Large) Urban |

23 |

6 |

29 |

| (Urban) Town |

12 |

10 |

22 |

| Rural |

6 |

5 |

11 |

| Total |

41 |

21 |

62 |

Lived experience interviews focused on experiences and impacts of 'repeat violence', which we encouraged participants to self-define. The interview topic guide steered the discussion towards repeated experiences of non-sexual physical violent victimisation in the recent past, but these experiences were also often inextricably linked to childhood experiences of neglect and abuse, institutional violence, domestic abuse and sexual violence, as well as engaging in violence and the drug economy. Interviews also explored participants' experiences and views on reporting violence and accessing support services (where appropriate).

Interviews took place between October 2022 and March 2023, and, with participants' explicit permission, were audio recorded using external and encrypted dictaphone devices. Where participants were recruited through third-sector organisations, we usually conducted interviews in a private room on the premises. This was beneficial to the research participant in terms of meeting in a familiar space and within which known support workers were closely available. We booked private meeting spaces within the local community (e.g., in community centres) or at the University to interview participants recruited through snowball sampling or who were accessing support through smaller organisations that did not have their own premises. Three participants recruited through social media advertising or snowball sampling preferred to use remote online video conferencing to take part in interviews. The average length of lived experience interviews was 61 minutes; they ranged between 20-130 minutes in length and amounted to almost 65 hours of recorded interview data.

Our in-depth qualitative interviews were conversational in style, meaning that they did not follow a tightly structured plan, but were responsive to the participant's mood, level of engagement, and the setting within which the interview took place. Though we used a topic guide to steer the conversation, no two interviews followed exactly the same structure, meaning that there were questions we asked some people and not others. This indicates that it is generally not possible – or appropriate – to present findings in terms of numbers or percentages. In-depth qualitative interviewing is especially effective when discussing sensitive subject matters since it encourages participants to direct the discussion, sharing as much or as little as they are comfortable with (Corbin and Morse 2003; Liamputtong 2007).

People with experience of substance use and trauma can have difficulty accessing memories of specific events and/or organising information about their past. This demands a sensitive approach, helping participants make sense of their experiences by focusing on critical moments to elicit shifting and overlapping fragments of their life story, which don't always link up in a linear sequence, but are nevertheless full of rich description, detailed interpretation, and biographical significance (Clifford et al. 2020; Harding 2006).

Stage 4: Analysis and write up

Data analysis was ongoing over several stages. At the end of each interview, we wrote up brief fieldwork notes, drawing together our initial thoughts about the key findings emerging from the discussions. This allowed us to regularly reflect upon the method and approach to inform, improve, and steer the remaining sessions. Fieldwork notes allowed us to keep track of the questions we asked of the data at various stages, while also encouraging us to reflect on and refine our research practice in the field.

In line with established protocols, interviews were sent to a third-party transcriber through the University's secure file transfer service to be transcribed verbatim. Interview transcripts were returned via the same manner to be fully anonymised by the research team, at which point we also populated a de-identified Excel spreadsheet listing contextual information about participants' circumstances. For example, the stakeholder spreadsheet included case study location, generic job titles, work sector, and interview format; the lived experience spreadsheet included case study location, recruitment route, gender, age, ethnicity, and housing type.

Next, informed by Braun and Clarke's (2019) pattern-based codebook version of thematic analysis, we began producing a working coding frame to build an analytical framework from the data considered against the research aims and objectives. We familiarised ourselves with the data and began identifying initial codes from the data based on patterns, questions, similarities, shared meanings and different understandings of experiences. We started to map data extracts against this initial list of codes to assist with refining codes into categories, which were then reviewed and clustered into thematic groups, devising descriptors to support coding reliability. These thematic categories were developed by reflecting on the initial list of codes and different thematic groups in relation to the research aims and objectives before being named and organised with sub-themes to denote different levels of themes. The data were then coded against the coding frame using qualitative data analysis software (NVivo 12), with the research team continually reflecting on the coding frame and thematic descriptors to facilitate the write-up of the research findings.

The analytical themes which emerged were used to order and structure the presentation of the data in the final report. However, a key focus of our analysis was not merely summarising the information provided by participants but moving beyond description by interpreting their views and experiences in light of the contextual data gathered (which included information pertaining to family, community and societal factors – in line with the WHO social-ecological model [Krug et al. 2002]). In addition, we wanted to make sure that the rich and textured detail that people shared in the interviews were not collapsed into patterns, clusters, and themes, or lost in data extracts. To illuminate the ways in which different forms and contexts of violence interact and reinforce one another, we developed a typology of lived experience (see Box 1) and made use of composite narratives to capture life course trajectories (Box 2).

Box 1: Typology of lived experience

The use of typologies has a long tradition in social research and involves grouping cases or participants into 'ideal types' based on their common features (Stapley et al. 2021). By combining careful attention to the construction of individual case studies alongside consideration of key similarities and differences between cases, and between groups of cases, typologies facilitate analytical interpretation via comparison.

Our approach to the development of lived experience typologies involved familiarising ourselves with the dataset by first reading interview transcripts and preparing written summaries of each individual participant. These summaries were then used to construct three ideal types, revisiting the interview summaries and making adjustments to the typology as necessary. This permitted a thorough exploration of the characteristics, circumstances, understandings, and experiences of all participants.

Box 2: Composite first-person narratives

Composite narratives combine data from several individual interviews to present a single life story (Willis 2019). They allow research data to be presented in an accessible way which acknowledges the complexities of individual views and experiences, whilst preserving anonymity and using the reflexive understanding of the researcher to depict a more generally representative account.

The story structure of each of our composite narratives was originally derived from 'optimal cases' most closely illustrating the pattern of experience represented in our lived experience typology. We then blended together excerpts from three or four other interviews in order to tell that story, changing small details and paraphrasing where necessary to present a single voice. Whilst the level and seriousness of violence recounted may seem extreme to some readers, each composite has been carefully constructed to faithfully represent an archetypal experience.

The three 'ideal types' identified were: unsettled lives, mutual violence and intermittent victimisation. Four composite narratives are presented, including two from the 'unsettled lives' group, to reflect the gendered experiences of men and women. Taken together, these analytical approaches contributed a more detailed and contextualised picture of repeat violence, allowing us to better capture the dynamic nature of repeat violence alongside its intersection with other forms of harm (including offending and criminalisation).

Once the final report was drafted, we arranged visits to a small number of differentially located stakeholder organisations to share our findings with groups of people with lived experience, peer mentors, volunteers, support workers, and service managers. We engaged with communities most impacted by the research to share the findings and recommendations as both a quality control check and to ensure that the research findings, and the way we have presented the work, resonated with people with lived and living experience of the issues. These feedback consultation sessions provided an open and collaborative space for communities to engage with the research, shape the recommendations, and consider how they might like the research to be translated into practice; they were especially useful while developing the accompanying research briefing papers.

Methodological issues

Sampling

Participants were recruited based on their experience of repeat violence, rather than identity characteristics such as age, gender or ethnicity – though we recognise that this means that there are important limitations and lessons to be learned about representation, as discussed in the section below.

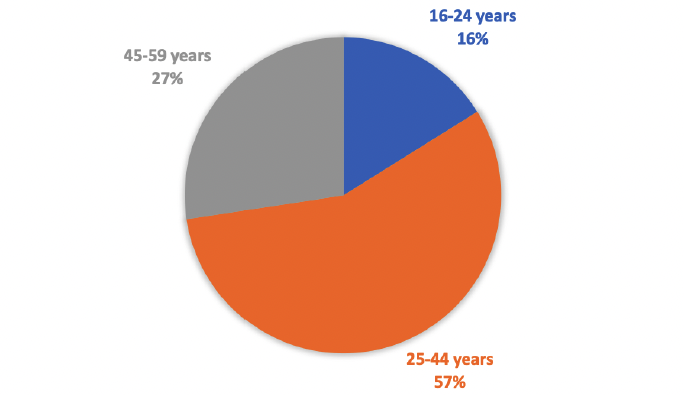

Approximately two-thirds of participants were men (65%, n=40) and one-third were women (35%, n=22). As illustrated in Figure 1, the majority (57%, n=35) were aged between 25 and 54 years. Just one participant described themselves as Black (2%, n=1) and the remainder as White (98%, n=61).

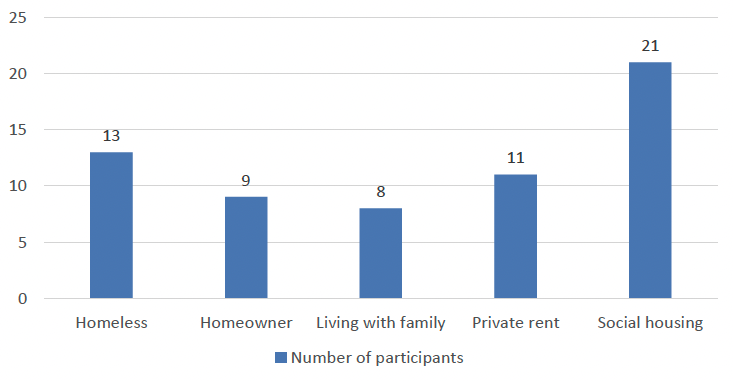

The housing circumstances across the sample were varied, around a third of participants (n=21) lived in social housing and just under a fifth (n=11) lived in privately rented accommodation. Nine people owned their own homes, including one who was left property in a family member's will, and eight people lived in family members' homes. Due to the nature of recruitment via homeless support organisations, we spoke to 13 people who were homeless at the time of research, most of whom were living in emergency accommodation such as hostels and temporary accommodation, but there was one participant who did not have accommodation arranged the night the interview took place. (This participant was accessing a third-sector homelessness organisation, which was helping him to secure accommodation when he was interviewed). Given that people experiencing homelessness are excluded from the Scottish Crime and Justice Survey, this is an important contribution to knowledge about violence within a deeply marginalised group.

Just under half of the participants (n=29) described themselves as unemployed at the time of interviews, while 20 people said they were employed, including one person who was self-employed. A further six people were volunteering, four people were full-time carers, and three people were undertaking training.

It is important to acknowledge that the method of recruiting participants through stakeholder organisations had a strong impact on how the final sample was constituted, reflected in the housing and employment circumstances of those who took part. Similarly, many stakeholder organisations were working with people in recovery from substance use, most of whom were aged over 25, affecting the age distribution of the final sample of participants with direct experience.

In line with approaches to generalisation in the context of qualitative research, the study did not set out to be representative of a broader population, or transferable to other contexts or settings (Lewis et al. 2014). Qualitative samples are usually small in size because the type of data they are intended to generate is rich in detail, rather than providing evidence of incidence or prevalence (Ritchie et al. 2014). There are aspects of the study which are analytically generalisable through the case study design and capacity for theory-building (Yin 2013). For example, the empirical data as well as our interpretative analytic approach, including the coding frame, can be used to support or complicate existing theories or develop new theoretical perspectives inductively from the data, thus contributing toward wider knowledge (Braun and Clarke 2013).

Challenges and limitations

There were several limitations to the study design and implementation. The Covid-19 pandemic was the most profound challenge to implementing the research as the national virus suppression measures, including lockdowns and social distancing, were introduced in March 2020 when fieldwork was originally planned to commence. The Scottish Government paused all in-person research projects until the risk status was acceptable; we were permitted to recommence fieldwork in April 2022 but had to revisit the research design to scale down agreed fieldwork activities to account for compressed timescales. Changes to the research design also acknowledged the impact of the aftermath of the pandemic on stakeholder organisations, many of whom were experiencing an influx of support uptake under constrained funding and, understandably, could not commit time or resources to assist with access requests.

These delays and restrictions had knock-on effects in all areas of fieldwork, including difficult decisions about resource priorities. There was a strong reliance on stakeholder organisations for recruitment and much of this work was taken up by the smallest organisations, often receiving the least funding, rather than national, securely funded, organisations. Larger organisations often had more access requirements, including research access request applications with lengthy response times which we did not have time or resources to complete. Recruitment through our own social media and printed poster advertising was not as successful as recruitment through established relationships with stakeholder organisations. As such, we acknowledged that people not connected with any kinds of support may not be well represented in the research; the decision to employ research assistants with lived experience created an important opportunity to access this particular group.

There were also important limitations to our original research design that impacted representation in the final sample. During the first phase of the project, stakeholders working with migrant communities and disabled people respectively highlighted the importance of an expansive understanding of violence to incorporate different forms of exploitation, and to acknowledge violence both within and beyond 'hate crime'. There were significant barriers to participants from migrant communities taking part in the research that we did not have resources to cover, including producing recruitment materials in other languages or securing interpretation and translation services to facilitate interviews. We had ethical approval in place for other inclusive methods, such as recorded verbal consent and participants requesting to have a supported person present in the interview, but these measures were insufficient to address English language barriers to participation. This is an important gap in the current project and further research would be welcomed by a range of organisations working with marginalised groups disproportionately affected by repeat violence, beyond a 'hate crime' definition.

Ethical considerations

The study was conducted in accordance with the British Sociological Association Ethical Guidelines and the British Society of Criminology Code of Ethics for Researchers in the Field of Criminology. Ethical approval was provided by the University of Glasgow's College of Social Sciences Ethics Committee, in accordance with procedures that conform to the standards set out in the ESRC Research Ethics Framework.

Sensitive research

The sensitivity of the topic raised important ethical issues around how to safeguard the emotional and physical well-being of participants, balancing confidentiality and anonymity with the obligation to inform relevant services should a participant disclose information about abuse, or an intention to harm themselves or others. As the study involved interviewing potentially vulnerable groups, there were also concerns around gaining valid informed consent and ensuring that no harm was caused due to participating in the research.

Whilst the study focused primarily on non-sexual physical violence against an individual person, we acknowledged the need to attend to the relationship between physical and other types of violence, as well as other crimes, as these came up during the fieldwork. Given the sensitive nature of the research topic and the expertise required in engaging with people who have experienced violent victimisation, we opted for a small research team of hands-on, interview-based researchers. This strong and shared foundation of experience and ethos meant that the research was designed to be mindful of the trauma and stigma that participants had potentially experienced, the marginalised position they inhabited, and the implications of these for ensuring informed consent and minimisation of harm.

Consent and confidentiality

Informed consent was sought from all participants and was supported through inclusive research strategies including all documentation being made available in an accessible format. Prior to all interviews, researchers spent time with potential participants to discuss the participant information documents and consent form, including informing participants of what the research was for, and what taking part would entail, as well as discussing the limits of confidentiality (see below). This approach, which balanced conversational discussion with the provision of clear information, supported participants to fully consent to participate in research by ensuring that the information provided was comprehensible and understood. In addition, consent was treated as a process rather than a one-off event; throughout the research we remained alert to signals that participants may wish to terminate their involvement, periodically checking whether they were happy to continue, and re-emphasising their right to withdraw from the project or opt not to answer any questions at any time and without giving a reason.

A limited guarantee of confidentiality was provided to all research participants, subject to a statement that information about imminent harm to themselves or others arising through their participation may be notified to appropriate authorities. Any decision to disclose such information depends upon the circumstances of the case, and we made it clear that this would always be a discussion. Our previous experience suggests that it cannot be assumed that a participant will want their situation reported – and in some cases it may further endanger participants if we were to do so. When we had concerns and were anxious that a participant might not seek support this was raised within the research team, and we reached a decision together about what to do next. Where stakeholder organisations assisted with recruitment and access and an issue came up in an interview or meeting, we asked participants to identify a trusted member of staff, volunteer or peer mentor whom they would be comfortable with us sharing concerns and ask that they be prioritised for urgent follow-up. We only had to do this on a couple of occasions. No similar concerns arose during interviews where no stakeholder organisation assisted with recruitment.

Harm minimisation and safeguarding

Stakeholders were consulted about the research design, including themes to be discussed, participant suitability, and methods, before seeking agreement to act as gatekeepers and interview location hosts. We arranged interviews in neutral, accessible, and familiar spaces so that participants felt supported and comfortable. Where this was not possible or suitable, we made alternative arrangements to host interviews on the University campus or in private meeting spaces within public buildings such as community centres. This responsive, informal approach was designed to make participation a positive experience. Some of our discussions inevitably precipitated memories of upsetting events, feelings of anxiety, sadness, and anger – on the part of research participants and the researchers. Throughout fieldwork, we were alert to signals of potential participant distress, responding sympathetically and appropriately in the moment, offering to take a break or stop the interview and re-establishing consent to resume. This required active listening and reassuring participants, and signposting to relevant support services or sources of advice from a pre-prepared list of local services and national helplines.

We had to cancel planned research activities on a number of occasions due to ongoing factors, concerns, or issues within the community or organisation, for example, dealing with loss.

Anonymisation and avoiding stigmatisation

The issue of stigmatisation was another important factor. Many of the participant groups in the study, alongside the neighbourhoods in which they lived, had a history of stigmatisation and there was a risk that the research may compound this, for example by reinforcing negative associations with violence and crime. We sought to mitigate this by adopting a research approach that was attentive to the strengths and resilience of participants and their communities. For example, we recognised that experiencing any kind of violence places extra demands on people's lives and the strategies that are employed to counter these effects have value and worth. We acknowledged the ways in which stigma can act as a powerful barrier to research participation and were mindful of the language used in consent materials and interview questions, and used participants' own preferred terminology as this came up (for example, some people did not wish to be referred to as 'victims' nor as 'survivors' but as a person with 'lived experience', 'on the receiving end of' or 'involved in violence'). By involving individuals, stakeholders, and wider communities in the research process at the earliest possible stage we tried to ensure that the research was respectful of the individuals and communities represented.

We decided to anonymise the case study areas in addition to de-identifying participant information including stakeholder job titles. To do so, we took great care in representing the context and detail participants provided to ensure that participants' identities are protected; in some cases, this required omitting information which might be identifiable due to public knowledge or media reporting of the incident, place, or persons involved.

Summary

This chapter has provided an overview of the research design, methods and data analysis protocols involved in the study. The reflections on the methodological challenges, ethical issues, and limitations of the study are intended to offer transparency to inform the reader about the process of qualitative research in practice, documenting how the research was designed, implemented, and written up.

Contact

Email: justice_analysts@gov.scot

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback