Vulnerable Witnesses Act - section 9: report

This report meets obligations on Scottish Ministers by the Vulnerable Witnesses (Criminal Evidence) (Scotland) Act 2019 to publish a report evaluating the effectiveness of the Act at supporting witnesses to participate in the criminal justice system and to set out next steps for implementation.

3. Context and background

Vulnerable witnesses’ experiences of the justice system

The challenges that vulnerable witnesses face when engaging with the criminal justice system are well-documented. Numerous studies conducted over many decades and across multiple jurisdictions have highlighted the additional barriers that specific groups face when giving evidence either as a victim of, or witness to, a crime (SCTS, 2015). In particular, this research has shown that for both children and adult victims of specific offences (i.e. sexual offences, domestic abuse, trafficking and stalking), the experience of giving evidence in Court is problematic for two reasons. Firstly, the experience of going to Court can feel intimidating, distressing and demeaning, particularly where they are required to give evidence of an intimate or personal nature which can be re-traumatising. Indeed, some vulnerable witnesses have described the experience of giving evidence in Court as worse than their experience of the crime(s) that they are giving testimony about (Brooks-Hay et al, 2019). Secondly, traditional methods of questioning vulnerable complainers in Court, particularly children, are known to be a poor way of eliciting accurate and relevant evidence (SCTS, 2015). As such, it restricts the capacity of these witnesses to fully “participate” in criminal proceedings by limiting their ability to provide information and evidence to the court and impacts on their well-being.

It is also important to note that there are other factors beyond giving evidence which have an influence on a vulnerable witness’ ability to participate in the criminal justice system. Delays in cases coming to trial and poor communication with witnesses by the police, courts and prosecutors are all known to have a material impact on the experience of vulnerable witnesses (SCTS, 2018). The length of time it takes for cases to come to trial has been significantly impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic and the resulting backlog of cases. These additional delays are likely to have heightened existing concerns and anxieties felt by vulnerable witnesses about the experience of giving evidence (Armstrong and Pickering, 2020).

While there continue to be delays in cases coming to trial as a result of the backlogs created by the pandemic, significant progress has been made in addressing this.

Support for vulnerable witnesses to give evidence before the introduction of the Act

Supporting vulnerable witnesses to participate fully in the criminal justice system has been a longstanding priority for those working across this system. There has been a progressive expansion of the scope and parameters of support as our understanding of the barriers that vulnerable witnesses face when interacting with the criminal justice system has evolved.

Under the legislation in place prior to the introduction of the Act (which is found in the Criminal Procedure (Scotland) Act 1995 as amended by the Vulnerable Witnesses (Scotland) Act 2004 and the Victims and Witnesses (Scotland) Act 2014), those who meet the definition of a vulnerable witness had (and continue to have) access to a range of different measures designed to support them while giving evidence.

The focus of these measures is on seeking to alleviate some of the pressure associated with giving evidence in the often intimidating environment of a courtroom or to address the fear that some witnesses experience in coming face-to-face with the accused. Accordingly, before the Act was in place, vulnerable witnesses had and indeed continue to have, access to the following measures which are designed to support them to give evidence at trial or an applicable hearing in which evidence is to be given:

- a live TV link to allow evidence to be taken remotely;

- the use of a screen to shield the witness from the accused;

- a supporter to sit next to the witness while giving evidence;

- a closed court which would exclude the public from the Court while the witness is giving evidence;

- taking evidence by a commissioner; and

- giving evidence in chief in the form of a prior statement

To optimise the effectiveness of these special measures, the legislation also permits vulnerable witnesses to access more than one special measure which can be used in conjunction with, or alongside, another provided that they are not incompatible with each other. For example, the legislation entitles vulnerable witnesses to use a supporter while giving evidence from behind a screen.

Support for vulnerable witness to pre-record their evidence ahead of trial before the introduction of the Act

The final two bullet points above relate to special measures which enable vulnerable witnesses to pre-record all or part of their evidence ahead of trial. The aim of these special measures is to restrict the amount of time that they would be required to spend giving live evidence at trial, in front of a jury, or remove the need for them to do so altogether. These special measures also enable vulnerable witnesses to provide their evidence in an environment that is alternative to the traditional court setting to support them in providing their best evidence.

Where the special measure of taking evidence by a commissioner is applied for and granted by the Court, an EBC hearing is fixed for the purposes of securing the vulnerable witness’ evidence. In addition to the witness, attendance at EBC hearings is restricted to a Commissioner appointed by the Court for the purposes of presiding over the hearing (a judge or sheriff); defence and prosecution as well as the clerk of court. The accused must be enabled to watch and listen to the proceedings, but is not permitted to be in the same room as the witness unless the court has granted leave on special cause shown. The witness is also entitled to have a supporter present at the hearing if they wish to do so and this is approved by the Court. The hearing is audio and visually recorded and this recording is played at trial as the witness’ evidence. This means the witness does not need to attend the trial and their evidence is captured earlier.

The special measure of giving evidence-in-chief in the form of a prior statement is an interview or a statement which is taken pre-trial (or before the applicable hearing in which the evidence is to be given), often during the investigation phase, which could be a video or audio taped interview between the witness and the police, a visually recorded interview between the witness, police and social worker (referred to as a Joint Investigative Interview(JII)) or a written statement that is then read out in Court. While the witness' evidence-in-chief can consist entirely of the prior statement, they may still need to provide evidence for cross-examination by the accused or their counsel which they may then be required to give in front of a jury or before a Commissioner. JIIs are formal interviews conducted with a child by trained police officers and social workers. They take place when there is a concern that a child is a victim of, or witness to, criminal conduct, and where there is information to suggest that the child has been, or is being, abused or neglected or may be at risk of significant harm. As these statements or interviews are usually obtained during the investigation stage by police, often the document or recording requires to be redacted or edited so as to remove inadmissible content.

The specific special measures which enable the taking of evidence by a commissioner and giving evidence through a prior statement, recognise that there are a number of advantages to enabling vulnerable witnesses to pre-record their evidence ahead of trial. Specifically, it enables those witnesses to give evidence out with the challenging and intimidating environment of a courtroom which promotes improved recall and enhances the reliability and accuracy of the evidence that they are able to provide (SCTS, 2018). The quality of evidence provided is further improved by allowing vulnerable witnesses to give their evidence earlier in the process supporting them to provide a more accurate and contemporaneous account (SCTS, 2018). This has become particularly important in the context of greater delays and lengthened journey times for cases after the COVID-19 pandemic.

Pre-recorded evidence is also associated with improved well-being for vulnerable witnesses compared to giving evidence in court. Earlier capture of evidence also supports healing processes to take place sooner, allowing the witness to move on with their life. This feature of pre-recorded evidence has been identified as particularly beneficial for young witnesses (SCTS, 2018).

Before the 2019 Act, however, the legislation gave greater prominence to those special measures intended to support witnesses to provide live evidence at trial.

While, as noted above, legislation did authorise the use of special measures which enabled evidence to be pre-recorded ahead of trial, these could only be adopted on a case by case basis after application by either the prosecution or defence and requiring the express agreement of the Court. By contrast, vulnerable witnesses, including children had an automatic entitlement to the following ‘standard’ special measures which supported them when providing evidence at trial:

- a live TV link allowing evidence to be taken from the witness remotely;

- the use of a screen to shield the witness from the accused while in Court; and

- the use of a supporter to sit next to the witness while giving their evidence.

Data published by SCTS prior to the implementation of the Act reflects that, of the 2,536 special measures applications for solemn cases made in 2018/19 and from which it is possible to infer when the evidence was taken, at least 92% were for special measures which supported vulnerable witnesses to give evidence at trial (Police Scotland et al, 2019).[5] Indeed, the vast majority of these applications were for the use of screens in the courtroom which accounted for 72% of the special measures applications lodged for cases heard in the solemn courts that year (Police Scotland et al 2019).

It is important to note that the Act does not repeal any of the existing legislation in place to support child witnesses but in addition, introduces a presumption in relevant cases, that a child’s evidence will be pre-recorded in advance of trial. As such, the full range of special measures listed above remain available for those child witnesses that do not fall under the definition of a relevant witness or to whom an exception to the presumption is granted by the Court.

The case for change

That vulnerable witnesses, in particular children, needed further support to enable them to fully participate in the criminal justice system was a key finding of the Scottish Court Service’s (now SCTS) judicially led Evidence and Procedure Review (EPR). Conducted between May 2013 and March 2015, the EPR reviewed the existing rules around evidence and procedure in criminal cases to explore opportunities to harness developments in technology as a means of reducing existing inefficiencies in the gathering of evidence, enhancing the quality of evidence collected from witnesses for trial and improving the treatment of vulnerable witnesses (SCTS, 2015). Following publication of the EPR, SCTS published a "next steps" report which set out measures that they intended to take in response to the findings and proposals which emerged from the EPR (SCTS, 2016). As part of the recommended new approach to taking the evidence of children and vulnerable adult witnesses a number of cross-justice working groups were established to look at and report on the pre-recording of evidence in chief and improving existing procedures for the taking of evidence by commissioner (SCTS 2017 (a) & 2017 (b)).

While the EPR was ostensibly about the rules and procedures around the gathering of evidence from vulnerable witnesses more broadly, it had a specific emphasis on the support and protections in place for child witnesses and victims. This recognised that children are particularly susceptible to the impact of aggressive questioning and delays in giving their evidence on both their wellbeing and their ability to give their best evidence (SCTS, 2015).

In conducting its review, the EPR found that, despite the existence of legislation permitting the courts to allow the evidence of vulnerable witnesses to be pre-recorded ahead of trial and the clear benefits that these provided to both child and vulnerable witnesses, these special measures were rarely sought (SCTS, 2015). To support this claim, the Review highlighted data from the three years between July 2011 and June 2014 which show that, of the 23,000 applications that were made to the Court for the use of special measures, just 1% were to seek the pre-recording of evidence ahead of trial (SCTS, 2015). Moreover, in some cases where the Court had permitted the evidence of a vulnerable witness to be pre-recorded, the EPR identified inconsistencies in the process being used by the Courts to capture this evidence which was resulting in applications being declined by the Courts or evidence being collected in multiple different ways from a single witness making it challenging for the Court to get a clear account of event. The EPR therefore called for a much greater use of pre-recorded evidence in order to capture the evidence of vulnerable witnesses supported by protocols designed to introduce a standardised approach to conducting these hearings (SCTS, 2015).

In considering options for enhancing the support available to vulnerable witnesses when giving evidence, the EPR drew on the experiences of other common law jurisdictions to consider their experiences of taking evidence from child and vulnerable witnesses ahead of trial. In doing so, the EPR identified the need for all parties to be prepared in advance of the EBC hearing and for a clear focus on the questions to be asked at the hearing (SCTS, 2015). In particular, the Review pointed to the use of ground rules hearings in a pilot of pre-recorded evidence conducted in England & Wales. The outcomes of this pilot found that these hearings were essential to ensuring adequate preparation ahead of the relevant hearing and to ensure that full advantage was taken of the opportunities afforded by pre-recording a witness’ evidence ahead of trial (SCTS, 2015).

The EPR also highlighted the opportunities of taking evidence from a vulnerable witness as soon as possible after the alleged offence had occurred in order to secure a more accurate and contemporaneous account of events and allowing witnesses to ‘move on with their lives’ (SCTS, 2015). That taking of evidence by commissioner supports vulnerable witnesses to provide their evidence earlier in the process was demonstrated by data collected by SCTS (SCTS, 2018b) as part of an evaluation into the impact of EBC hearings on vulnerable witnesses. This found that, of the 25 EBC hearings conducted in 2017, the witness was, on average, able to provide their evidence eight weeks earlier in the process compared to if they had given their evidence at trial. In two instances, the vulnerable witness was able to give their evidence over 16 weeks ahead of trial (SCTS, 2018b).

The findings of the EPR demonstrated that the use of special measures which enable child and vulnerable witnesses to pre-record their evidence ahead of trial is associated with enhanced participation in the criminal justice system. In particular, this approach supports vulnerable witnesses to provide information to the Court by enabling them to provide a more accurate and contemporaneous account. It also promotes improved wellbeing among vulnerable witnesses associated with the experience of giving evidence by enabling them to do so earlier and in a less daunting and intimidating environment.

Following the EPR, the High Court introduced two separate practice notices (Practice Note No.1 of 2017 and Practice Note No.1 of 2019) setting out processes that prosecution and defence counsel should follow when seeking pre-recorded evidence (High Court of Justiciary, 2017) and which set out expectations on counsel for preparing questions ahead of an EBC Hearing (High Court of Justiciary, 2019).

Baselining the use of pre-recorded evidence in the High Court

In 2018, following the introduction of Practice Note 1 of 2017, SCTS published an evaluation paper which provided data relating to applications for EBC hearings in the High Court for the whole of 2017 and ten months of 2018. The aim of this evaluation was to provide a quantified baseline to support future performance monitoring around the use of pre-recorded evidence in the High Court (SCTS, 2018b).

Applications for EBC

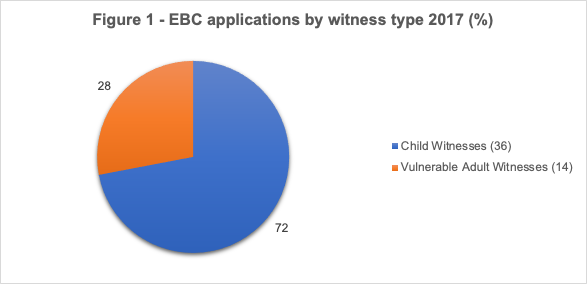

Data from this evaluation demonstrated that during 2017, a total of 50 applications were made for EBC hearings to be conducted in the High Court. 36 (72%) of those applications were for child witnesses while the remaining 14 (28%) were for vulnerable adult witnesses (SCTS, 2018b).

N= 50 EBC hearing applications

EBC hearings conducted

In tracking these applications through the court system, the evaluation identified that, of the 50 applications for EBC hearings that were made to the High Court during 2017, 33 (66%) of those progressed to a procedural hearing for an application to be determined by the Court. The reasons why 17(33%) of applications for pre-recorded evidence did not progress to a procedural hearing are set out at Figure 2 below.

N= 17 EBC hearing applications that did not progress to a procedural hearing

Of the 33 applications that progressed to a procedural hearing, all were approved by the Court and 29 (88%) progressed to an EBC hearing (SCTS, 2018b). 4 (12%) did not progress to an EBC hearing either because the Crown did not proceed with the case or because the witness either did not attend or withdrew in advance from the hearing. (SCTS, 2018b).

EBC recordings played at trial

The evaluation further shows that, of the 29 EBC hearings that proceeded, 25 (86%) of those recordings were played at a relevant trial diet with 4 (14%) not being played at a trial diet (SCTS, 2018b).

N= 29 EBC hearing recordings

Of the 4 recordings that were not used at trial, 1 was not played because a guilty plea was tendered by the accused at the trial while the remaining 3 were not played because COPFS did not proceed with the case (SCTS, 2018b).

In addition to the data for 2017, the Evaluation Report also provided data on applications for EBC hearings covering the first 10 months of 2018. This demonstrated a significant increase in the use of the special measure of taking evidence by a commissioner from the previous year. Specifically, it showed that a total of 133 applications for EBC hearings had been submitted between January and October 2018. The number of applications for EBC hearings submitted each month during 2017 and the first 10 months of 2018 is set out at Table 1 below.

| Applications for EBC hearings | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child Witnesses | Vulnerable adult witnesses | |||

| 2017 | 2018 | 2017 | 2018 | |

| January | 1 | 2 | 0 | 3 |

| February | 1 | 9 | 0 | 5 |

| March | 8 | 7 | 4 | 0 |

| April | 1 | 17 | 0 | 1 |

| May | 3 | 12 | 0 | 4 |

| June | 0 | 13 | 1 | 3 |

| July | 4 | 17 | 0 | 1 |

| August | 0 | 12 | 1 | 2 |

| September | 11 | 10 | 2 | 5 |

| October | 6 | 6 | 1 | 4 |

| November | 1 | - | 3 | - |

| December | 0 | - | 2 | - |

| Average applications per month | 3 | 11 | 1 | 2 |

Statistics on applications for EBC hearings in 2017 have been used in this report as the baseline data for the purposes of evaluating the efficacy of the Act at supporting relevant witnesses to participate in the criminal justice system. The reason for this is that a full year’s worth of data is available for 2017 and because the Evaluation Report provides additional information on the progress of EBC hearings from application to a recording of the evidence being played at trial which is not available for 2018.

Contact

Email: prerecordedevidence@gov.scot

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback