Reusable nappies: research

Provides commentary on a range of motivations and barriers associated with reusable nappies and makes a number of recommendations to encourage increased uptake among families in Scotland.

4 Findings: Motivations and barriers influencing uptake of reusable nappies

4.1 Existing evidence on motivations for uptake of reusable nappies

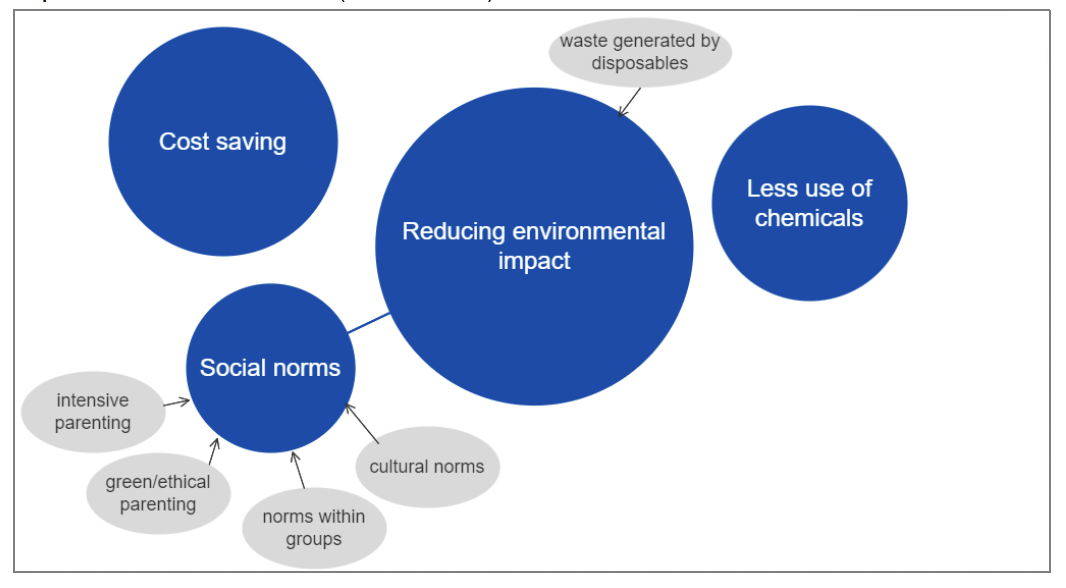

The rapid evidence review found several sources exploring parents’ motivations for using reusable nappies. Reducing environmental impact emerged fairly consistently as the greatest driver of uptake, however cost savings were also highlighted as an important consideration, along with perceptions about the naturalness of reusable versus disposable nappies and beliefs about implications for babies’ health. The motivations highlighted in the review are summarised in Figure 2 and explored in more detail below.

4.1.1 Reducing environmental impact

By far the most common reason for uptake of reusables, cited both by parents and by operators of nappy schemes or services in the academic and grey literature, is to reduce the environmental impact of nappy use (Askins & Bulkeley, 2005; Pendry et al., 2012; Watson et al., 2023). In a 2005 UK-based survey of reusable nappy users, 83% reported choosing reusable nappies because they are more environmentally friendly (Environment Agency, 2005b). Specifically, concerns about the volume of waste associated with disposable nappies, which is very visible and tangible, and the idea of this waste going to landfill are strong motivators (Askins & Bulkeley, 2005; Uzzell & Leach, 2003). Cloth nappy users were noted as being well informed about the environmental impacts of reusable versus disposable nappies, and often express a strong sense of environmental identity and emotional connection to environmental issues (Askins & Bulkeley, 2005; Pendry et al., 2012).

At the same time, environmental concern does not necessarily lead to reusable nappy use. The literature highlights tension and even guilt felt by parents using disposable nappies around the waste generated (Pendry et al., 2012). In some cases, parents highlighted ways in which other pro-environmental behaviours undertaken were felt to offset, or compensate for, the waste generated by disposables (Gibson et al., 2013; Pendry et al., 2012). Others questioned the overall impact of a family switching to reusables, highlighting other environmental impacts e.g. energy use in laundering (Pendry et al., 2012).

The actual environmental impacts of nappy choices have been explored in the literature, particularly through the use of Life Cycle Assessment approaches which estimate the various environmental impacts associated with production, use and end-of-life phases of nappy product lives (see Box 1).

4.1.2 Cost effectiveness

Overall cost savings are another commonly reported motivation for choosing reusable nappies (Environment Agency, 2005b; Pendry et al., 2012). In the 2005 UK study, 68% of reusable nappy users surveyed reported reusable nappies being cheaper/more economical as a reason for use (Environment Agency, 2005b). Saving money was discussed as a primary motivation for participants in reusable nappy incentive schemes including voucher schemes (Warner et al., 2017) and a pilot project providing a free reusable nappy kit (Renkert & Filippone, 2023). Development research for Scotland’s baby box initiative found that, for some low income families, the potential inclusion of reusable nappies was viewed as favourable due to the potential for cost savings (Scottish Government, 2017a). At the same time however, potential cost savings are often not seen as being persuasive enough to overcome the barriers to use of reusable nappies (See section 4.3) (Askins & Bulkeley, 2005; Scottish Government, 2017a).

4.1.3 Avoiding chemicals in disposable nappies

Another reason for choosing reusable nappies, highlighted in multiple sources, relates to the use of chemicals in disposable nappies. In the 2005 UK survey, 31% reported being motivated to use reusable nappies because they contain less chemicals than disposables (Environment Agency, 2005b). Qualitative research highlighted that some cloth nappy users disliked disposable nappies for reasons including their use of chemicals and are motivated to reduce exposure to these for health reasons (Askins & Bulkeley, 2005; Pendry et al., 2012; Renkert & Filippone, 2023; Wilks, 2004).

Box 1: Environmental impacts of nappy choices – evidence from Life Cycle Assessments

Studies have found that although end of life scenarios for disposable nappies may feature strongly in the environmental footprint (Defra, 2023), this is very dependent on region (Ng et al., 2013) and method of rubbish disposal (Velasco Perez et al., 2021), with unsanitary landfill showing increased impacts (United Nations Environment Programme et al., 2021; Hoffman, 2020). Exploration into recycling options show the potential for reducing impact (United Nations Environment Programme et al., 2021), but this needs further investigation. Routinely initial production stage and raw materials are identified as having the highest impact in the disposable nappy lifecycle (Defra, 2023; Velasco Perez et al., 2021). As a result, the responsibility for reducing the environmental impact in disposable nappies lays with the manufacturers, with a decrease in weight since the initial impact studies in the UK (Environment Agency, 2005a, 2008) credited for a 27% reduction in the resulting carbon footprint (Defra, 2023).

Conversely, with reusable nappy usage, the onus for reducing environmental impact lays with the user, with laundering highlighted as the main contributor. Though it is generally concluded that reusable nappies have the potential to be lower in carbon footprint, this is dependent on optimised washing behaviour (washed in cold water and line dried ((O’Brien et al., 2009), with increased wash load size (Environment Agency, 2005a). Use of alternate methods, e.g. tumble drying, can increase the resulting carbon footprint and have the potential to cause substantial overlap (United Nations Environment Programme et al., 2021) with carbon impacts from using disposables. Criticisms have been raised about the likelihood that users will chose to use the optimised behaviour over convenience of using of a tumble dryer (Daae & Boks, 2015). As a result, education might be required to increase the likelihood of achieving lowered impacts (United Nations Environment Programme et al., 2021). The Environment Agency (2005a) found no benefit in carbon footprint from the use of commercial nappy laundry services, but a more modern study set in Brazil (Hoffmann et al., 2020) found them beneficial. This discrepancy may be down to geographic and behavioural differences, or may be due to increased efficiency between systems in 2005 and 2020. United Nations Environment Programme et al., (2021) provide a matrix for policymakers, to help guide decisions on whether disposable or reusable systems might be more appropriate to support based on context (geographical, technological and behavioural). Where people are already eco-conscious, reusables are a favourable option. The exception to this is in instances where there are poor laundering services, electricity that has a high carbon footprint or low number of uses per nappy. In countries/regions where consumers may be considered as indifferent, the matrix recommends disposables as the most appropriate option, except in instances where there is a high likelihood of inappropriate disposal of the single use nappies (classed as littering, flushing down the toilet or disposed of with recyclables). It is noted by the authors that electricity price might increase the likelihood of optimised laundering behaviour, though perhaps it might also effect the likelihood of someone choosing to use renewable nappies in the first place.

Though reusable nappies have the potential to be lower in carbon footprint than disposables, this is not true of all environmental impacts. In a total of 18 impact categories, reusables only showed lower impacts in 7 categories (GWP, fresh water eutrophication, terrestrial ecotoxicity, human non carcinogenic toxicity, land use, fossil resource scarcity and water use) while disposables remained lower in the remaining 11 (stratospheric ozone depletion, ionizing radiation, ozone formation-human health, fine particulate matter formation, ozone formation – terrestrial ecosystems, terrestrial acidification, marine eutrophication, freshwater ecotoxicity, marine ecotoxicity, human carcinogenic toxicity, mineral resource scarcity) (Defra, 2023). This shows that there is a trade-off between the two systems, and which system is considered preferential may be down to individual interests.

4.1.4 Social pressures and social norms

Although the majority of parents use exclusively disposable nappies, the literature highlighted ways in which social pressures can act upon nappy choices in favour of reusables. Nappy choices can be tied up with perceptions around what constitutes good care – Randles (2022) notes social pressures placed on parents, particularly mothers, to be seen to parent intensively and demonstrate high levels of care. These can include pressures to adopt ethical and environmentally sustainable parenting practices (Randles, 2022).

At the same time, social norms can operate differently within different groups – social influence tends to be strongest in relation to norms of reference groups that we identify strongly (Masson et al., 2016). Askins and Bulkeley (2005) noted increasing social pressure to use reusable nappies, in the context of rising use amongst middle class parents. This raises questions about how reusable nappy use has changed more recently amongst different groups. Wider literature on pro-environmental behaviour indicates that normative influences operate not only though perceptions of what other people think we should do (injunctive norms) and, more importantly, what other people actually do (descriptive norms) but also the information we glean about how others’ behaviour is changing over time (dynamic norms). Where we detect that adoption of a behaviour is increasing, this can motivate change even when the behaviour is still relatively marginal (Sparkman & Walton, 2017).

Having prior experience of reusable nappies, both through personal experience and through familiarity with them because friends and family use(d) them has the potential to motivate uptake of schemes promoting reusable nappies. One study in the US had exceptionally high uptake among refugee families from countries in the global south where reusable nappies are the norm, and amongst whom reusable nappies were familiar and preferred (Renkert & Filippone, 2023).

4.1.5 Other benefits associated with reusable nappies

Whilst the focus above is on what motivates parents to choose reusable nappies in the first place, the literature also highlights a number of benefits of reusable nappies that encourage users to continue reusable nappy use in the long term, referred to as ‘stay factors’ by Pendry et al. (2012). These include: satisfaction with the performance of reusable nappies, which may exceed initial expectations regarding leakage etc., aesthetic aspects of reusable nappies, social connections developed with other users, and having a consistent supply of nappies (Pendry et al., 2012; Renkert & Filippone, 2023).

Pendry et al. (2012) found that users valued the range of choice and aesthetics of reusable nappies and wraps, with colourful designs felt to be fashionable and appealing (although not universally appreciated, see Section 4.3.5). Some users discussed developing a strong interest in different designs and a ‘buzz’ from adding new ones to their collection. The idea that cloth nappy use can become an interest, even akin to a hobby, rather than just a purely instrumental consumer choice, is reinforced by the development of communities of interest among cloth nappy users. The social connections developed through engaging with user communities, especially online, was reportedly highly valued by some users (Pendry et al., 2012).

4.2 Insights into motivations from focus groups

A number of the prompts used in the focus groups sought to explore what motivated use of cloth nappies (see Appendix B). It is important to highlight the varying levels of experience with cloth nappies within the focus groups, as the motivations found in the focus groups particularly covered the motivation to ‘try’ cloth nappies, with very few participants maintaining this choice long term. Of the eight participants in our focus groups that had tried reusable nappies, only four had used them for a significant amount of time (here, classed as a minimum of 4-5 months). The remaining four participants had some experience with cloth nappies but did not continue using them shortly after their first attempts. Notably, only one participant had maintained use of cloth nappies with all children for the entirety of their early years before potty training. Another participant used cloth nappies up until potty training completion for the first child but did not continue use with their later children. This is reflected on further later in the discussion about the barriers to uptake and sustained use of cloth nappies (see section 4.4).

Box 2: What motivated focus group participants to use/try cloth nappies?

- Cost savings

- Concerns about environmental impact of disposables

- Kinder materials for baby’s skin (plastic-free)

- Facilitating potty training & weaning off nappies altogether

- Advice and gifted nappies from parents & grandparents

- Seeing friends use cloth nappies for their children

Although environmental reasons were acknowledged as being of importance, cost was the major driver for two of the longest users of the nappies. One participant had been given a set of reusable nappies by his mother as he had his first child younger in life when financially tight. The other participant knew about environmental reasons for using reusables but stated that his primary motivation was the cost factor, appreciating that it would be cheaper in the long run. Of the two remaining longest users, one had been motivated by both environmental concerns and cost, having bought her nappies second-hand. The other had been primarily motivated by environmental concerns and not wanting to put plastic next to her baby’s skin. However, when prompted further to consider what environmental factors might influence their nappy choices, regardless of whether they had tried reusables or not, the environmental motivations highlighted were primarily around the concern about how much landfill space would be taken up by a baby’s worth of disposables. The environmental costs associated with nappy production were not mentioned. Several participants voiced the belief that some disposables were biodegradable but were concerned over how long decomposition would take. Participants were not aware that most disposable nappies would in fact end up being incinerated rather than going to landfill. Notably, while cost savings motivated some participants who used cloth nappies, cost was also highlighted as a barrier to uptake of cloth nappies (as explored later in the report).

One of the current users of reusables was not in fact using nappies per se but washable potty training pants, and another participant also spoke about using reusables as a step towards potty training, as they allow the child to feel when they are wet (unlike the more absorbent design of many disposables which aim to provide a “dry feel” for comfort). It was widely agreed that promoting reusable nappies for use at this stage in a child’s development would be a positive step. Participants noted that by using cloth nappies to transition away from nappy use altogether might make potty training less ‘messy’, as accidents would be ‘contained’ better by the design of cloth nappies. Additionally, the use of washable and reusable cloth nappies throughout potty training was thought to reduce the likelihood of children’s clothes being soiled frequently and therefore needing to be washed or thrown away.

Interestingly, COVID-19 lockdowns were mentioned as a factor that may have facilitated people’s commitment to using reusables. Firstly, because people had more time to keep on top of the extra washing, and secondly because households were not being visited by friends/family members who might have questioned why reusables were being used;

“I don’t think my mum had much dealings with me through that first year due to lockdown reasons… I think a lot of people would be saying why are you dealing with that? I think people would think that’s unhygienic, that’s just a faff, you’ve got enough to worry about” (Focus Group Participant).

The influence of family and friends appeared to be both a motivator and a potential barrier to reusable nappy use, if they are vocal about their negative perceptions of reusable nappies.

4.3 Existing evidence on barriers to uptake of reusable nappies

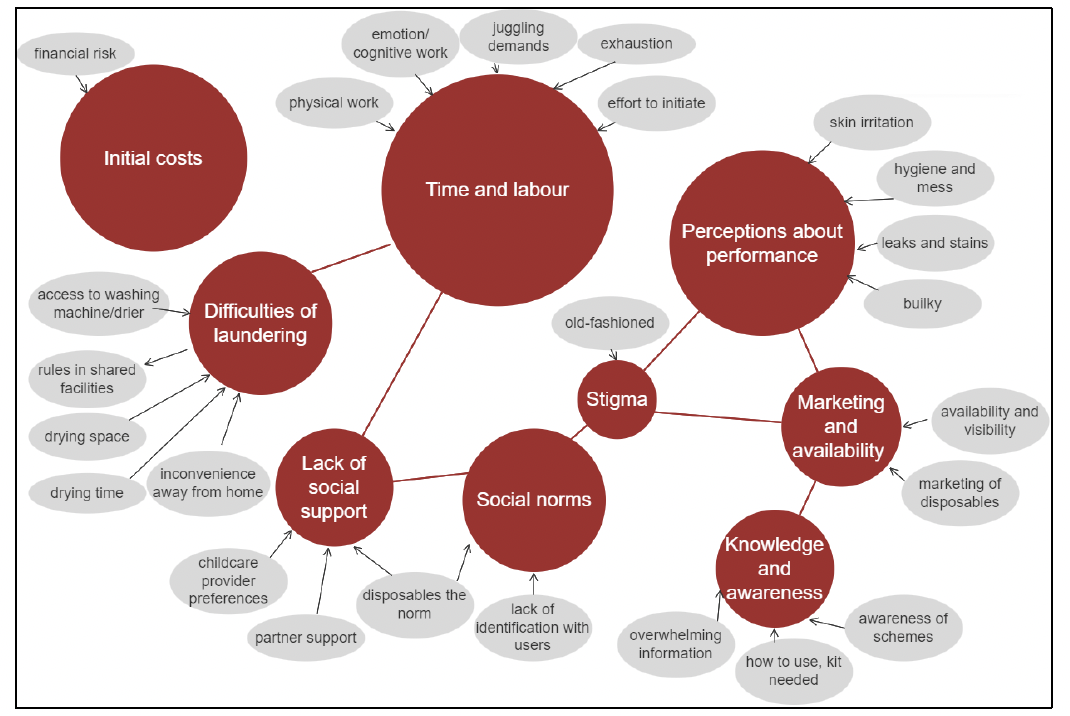

The review explored a wide range of material highlighting barriers to uptake of reusable nappies. Overall, there appears to be a well-established body of evidence on the wide range of barriers experienced, and they appear fairly consistent across studies and geographies represented within the review. There was no discernible change in the perceptions of barriers over the 20-year timeframe of the published literature reviewed. Figure 3 gives an overview of the barriers identified and some of the interconnections between these, with the following sections exploring these in more detail. Many of the factors that discourage parents from trying reusables are also reported as challenges experienced by those trying out or using reusables, although in some cases anticipated challenges did not match actual experience.

4.3.1 Time and labour

Time and labour associated with reusable nappies is noted consistently as a major barrier to their uptake and would appear to be the greatest factor constraining their use (Miller et al., 2011; Pendry et al., 2012; Randles, 2022; Renkert & Filippone, 2023; Siemensma & Hunter, 2007). A number of studies explored the ‘care work’ associated with reusables, which includes not only the physical work of laundering nappies, but also a cognitive and emotional burden associated with planning schedules for washing and drying, tracking supplies, and remembering multiple components to pack when leaving the house (Pendry et al., 2012; Randles, 2022). Of particular concern is the gendered nature of this care work, with women shouldering a disproportionate amount of the burden (Randles, 2022). Whilst in a few cases, the time and labour involved in laundering is described using terms like ‘inconvenience’ or ‘hassle’, qualitative research highlights that it is not simply a case of reusables being somewhat less convenient than disposables. Rather, the extra demands can seem insurmountable for parents, particularly mothers, who are facing a ’tightly calibrated juggling act’ (Randles, 2022) of caring and paid work responsibilities resulting in an existing experience of time pressure. At the same time, new parenthood is a time where many are already feeling exhausted and ‘worn out’ and may already be struggling to keep up with existing levels of laundry and other household tasks (Pendry et al., 2012). Even for those already comfortable with using reusable nappies, growing families mean more care work and busier schedules that can act as a barrier. Some families who used reusables with a first child reported switching back to disposables for second and/or subsequent children for this reason (Askins & Bulkeley, 2005).

The literature also highlighted the time and effort expended to make the initial transition to reusable nappies. Getting started with reusables can seem like a ‘daunting process’ for parents who already feel too busy, involving having to get in touch with a local cloth nappy agent (Pendry et al., 2012), or spending time researching different options (Askins & Bulkeley, 2005; Siemensma & Hunter, 2007). As well as learning how to use reusables themselves, a parent driving the choice to use reusables may also find themselves having to teach other family members how to use them or taking on a greater share of nappy changing responsibilities (Askins & Bulkeley, 2005; Pendry et al., 2012).

At the same time, however, established users argued that laundering cloth nappies does not involve as much time and hassle as people think (Miller et al., 2011; Pendry et al., 2012), echoed by participants in a reusable nappy trial scheme who reported feeling pleasantly surprised that reusables were easier than initially expected (Siemensma & Hunter, 2007). This suggests that once laundering of reusables becomes part of established routines, the extra work involved is often less challenging than anticipated.

4.3.2 Difficulties of laundering

In addition to the time and labour involved, the literature examines various practical challenges in laundering reusable nappies experienced or anticipated by parents. These include not having a washing machine and/or tumble drier at home (Randles, 2021, 2022; Renkert & Filippone, 2023; Sadler et al., 2018). For those relying on shared laundry facilities or laundrettes, concern about the extra costs and rules against laundering reusables may pose a further constraint (Barreca, 2023; Randles, 2021; Sadler et al., 2018). A lack of space for drying nappies and general concerns about being able to get nappies dry or the time taken to dry were also highlighted (Askins & Bulkeley, 2005; Kok, 2018; Pendry et al., 2012; Renkert & Filippone, 2023). Whilst space for drying is discussed more in relation to outdoor drying space in the literature, in the Scottish climate indoor space for drying during winter or in wet weather is also likely to pose a challenge.

Laundering can also pose practical problems when on holiday or staying away from home (Askins & Bulkeley, 2005; Pendry et al., 2012). Many reusable nappy users overcome this by using disposables for convenience in these situations (Askins & Bulkeley, 2005; Environment Agency, 2005b).

4.3.3 High initial costs

Another key barrier to uptake of reusable nappies relates to the upfront financial costs (Miller et al., 2011; Pendry et al., 2012; Scottish Government et al., 2021; Thompson et al., 2011; Watson et al., 2023). Whilst using disposables can work out more expensive in the long run (Defra, 2023), buying reusable nappies requires a more considerable initial investment. Part of the challenge of this for parents is that it may be seen as a risky investment, as there is a chance that money will be wasted if reusables are not felt to work for the family, or if the particular type or brand of reusable nappy purchased is not well suited (Pendry et al., 2012; Scottish Government et al., 2021).

Online communities (including those focused on resale of reusables) are mentioned in the literature as valued by existing users (Pendry et al., 2012), and literature on the impacts of reusables notes that acquiring reusables second hand can further reduce environmental impacts (Copello, 2021). However, the review did not find evidence on parents’ attitudes to second hand cloth nappies or the potential for new users to reduce the initial costs through buying second hand kits.

4.3.4 Perceptions about performance and associated stigma

Several sources in the review highlighted negative perceptions about the performance of reusable nappies as a barrier to switching from disposables. These included viewing reusables as less hygienic, dirty or messy, less efficient/more likely to leak, or likely to stain (Askins & Bulkeley, 2005; Kok, 2018; Randles, 2022; Scottish Government, 2017a). Reports of actual performance of reusables was mixed. Some users or trial participants reported more leaks with reusables (Renkert & Filippone, 2023), however others experienced reusables as equally effective or better than disposables at preventing leaks (Pendry et al., 2012). Overnight leaks were mentioned by some (Renkert & Filippone, 2023), and some users/trial participants preferred to use disposables at night (Environment Agency, 2005b; Siemensma & Hunter, 2007).

Another common perception was that reusables were more likely to lead to skin irritation, through nappy rash or rubbing due to poor fit (Miller et al., 2011; Pendry et al., 2012; Randles, 2022; Renkert & Filippone, 2023). While some trial participants reported increased problems with rashes (Renkert & Filippone, 2023), other sources report no association between reusable nappies and incidence of nappy rash, with more frequent changing of reusables to ensure dryness (Geist & Bammer-Zimmer, 2023). As the review focused on attitudes, behaviour and experiences of parents, a review of the medical evidence on impacts of nappy choices on incidence of nappy rash was outwith the scope of this project.

Children’s discomfort was reported as a challenge experienced by participants in a pilot project providing free cloth nappy kits; these included children feeling wet, removing their nappies, complaining about the bulkiness of the nappy (Renkert & Filippone, 2023). The relative bulkiness of reusables compared to disposables was also mentioned as offputting in a qualitative study of Scottish parents, who were unsure how well they would fit under baby clothes) (Scottish Government, 2017a).

Several sources highlight perceptions amongst parents that reusable nappies are outdated or old-fashioned (Askins & Bulkeley, 2005; Scottish Government, 2017a). Some of these perceptions could relate to a lack of awareness about the range of modern cloth nappies available and enduring images of reusable nappies as basic cloths secured with pins (Askins & Bulkeley, 2005; Randles, 2021). The issue of stigma associated with reusables was explored in depth in a recent US study which illustrates how strongly nappy practices are associated with care and the performance of good parenting (Randles, 2021, 2022). In this study, low-income mothers perceived that putting their child in reusables, which they associated with being leaky and smelly, would mark them as poor, reflect badly on their parenting and put them at greater risk of attracting the attention of social services. At the same time, reusables were simultaneously described as being a middle class privilege, highlighting how reusable nappies may be seen as both a symbol of poverty and affluence. The meanings associated with reusable and disposable nappies may be in part shaped by marketing and branding of disposables (explored in section 4.3.6).

4.3.5 Social systems, norms, and support

Perceptions of reusable nappies also link to social norms around their use. Disposable nappies are by far the most common nappy choice, and the fact that they are seen as the ‘default’ (Kok, 2018) and choice of the majority has a strong influence on those who are not highly motivated to diverge from this norm (e.g. for environmental reasons) (Pendry et al., 2012). As well as perceiving that disposables being the most popular choice must mean they are better (Pendry et al., 2012), this can also mean that most people do not have the opportunity to become familiar with reusables through friends and family using them (Scottish Government, 2017a). Disposables being the default choice, combined with high level of satisfaction with disposables’ performance, can mean that most have no desire to change (Siemensma & Hunter, 2007).

The review highlighted that reusables can be seen as a niche choice adopted mainly within certain groups. Lack of identification with cloth nappy users, who may be perceived as ‘hippy’ or alternative (Pendry et al., 2012) can put off those who do not see themselves as fitting within that group. There is not enough evidence from the literature to comment on whether this perception is changing over time. Whilst bright colours and designs can be an appealing feature of reusables (Pendry et al., 2012), a study in North East England found that white nappies were more popular, with bright nappies seen as fitting with a ‘hippy style’ and offputting for some (Askins & Bulkeley, 2005).

Norms around use of disposables can also lead to a lack of social support for adopting reusables. In the absence of family and friends who use reusables, having access to social support in the form of formal and informal networks and trusted actors to advise is especially important (Askins & Bulkeley, 2005; Kok, 2018; Renkert & Filippone, 2023; Warner et al., 2017). Some sources argue that formal parental support systems such as health visiting and maternity services are biased towards disposables, presenting them as the default and participating in their marketing through newborn ‘Bounty’ packs consisting of marketing material, samples, vouchers etc. (Askins & Bulkeley, 2005; Thompson et al., 2011). Social support within the household is also an important factor – a lack of support by partners is noted both as a barrier to uptake and a reason for switching back to disposables after previously using reusables (Askins & Bulkeley, 2005; Kok, 2018; Pendry et al., 2012).

4.3.6 Availability and marketing

Reusable nappies also can be at a disadvantage competing in a market dominated by long-established disposable nappy brands. The easy availability of disposable nappies at any supermarket or convenience store contrasts with that of reusables, which suffer from limited availability in physical shops and therefore less general visibility (Pendry et al., 2012). Purchasing of reusables often occurs online, which can limit those who do not have access or use the internet, or who do not know where to look to buy reusables online (Pendry et al., 2012). At the same time, disposables benefit from a long history of heavy marketing by leading brands, including targeted marketing to parents of newborns, resulting in strong brand images and a high level of trust and consumer loyalty (Askins & Bulkeley, 2005; Buckingham & Kulcur, 2009; Pendry et al., 2012; Randles, 2021; Thompson et al., 2011). The relative absence of marketing of reusables, including lack of vouchers and incentives targeting new parents, along with lack of awareness of available schemes is argued to constrain uptake of reusables (Pendry et al., 2012).

4.3.7 Knowledge and awareness

Another important barrier to uptake highlighted in the review relates to knowledge and awareness around reusable nappies. This includes general lack of awareness about reusables and how modern cloth nappies have evolved (Askins & Bulkeley, 2005; Kok, 2018), uncertainty about how to use reusable nappies, what components and how many nappies would be needed for a full kit (Scottish Government, 2017a), and lack of awareness of schemes supporting reusable nappy uptake (Pendry et al., 2012; Salhofer et al., 2008).

Rather than reporting a lack of information on reusables, the literature highlighted that parents may feel that there is an overwhelming amount of complex information available (Kok, 2018). At the same time, this information may not reach those that do not actively seek to research reusable nappies (Kok, 2018). Several sources discuss the main information sources relied on with respect to reusable nappies, with friends and family highlighted as most important (Askins & Bulkeley, 2005; Pendry et al., 2012; Warner et al., 2015) and word of mouth as a key vehicle by which users are introduced to reusable nappies (Askins & Bulkeley, 2005). The internet, peer networks and user communities, local councils, and private sector actors like nappy reps can also form important trusted sources of information (Askins & Bulkeley, 2005; Pendry et al., 2012; Warner et al., 2018).

4.4 Insights into barriers from focus groups

As mentioned earlier, many of the focus group participants who had experience with cloth nappies did not maintain their use long term. Additionally, the participants that solely used disposable nappies had many reservations about cloth nappies which deterred participants from attempting to try the alternative temporarily. A number of barriers to uptake and sustained use were highlighted throughout the focus group discussions, with participants generally stating that disposable nappies continue to be the default and that there is much work to be done in order to enable and mainstream the use of cloth nappies. Suggestions from participants on interventions to encourage the uptake of reusable nappies are noted later in the report (section 5.3).

Box 3: barriers to reusable nappy uptake identified in focus groups

- Lack of awareness about cloth nappies and how to use them

- Lack of visibility of cloth nappies in supermarkets

- Overwhelming amount of parental responsibilities (new parents, single parents, parents with multiple children)

- Social perceptions (unnecessary hassle, unhygienic)

- Time & effort required for laundering

- Large upfront cost (cloth) compared to small regular purchases (disposable)

- Energy costs of laundering nappies

- Hygiene concerns (cleanliness of reusing nappies on young children)

- Hygiene concerns (storing and washing soiled nappies not appealing)

4.4.1 Knowledge and awareness

It was made apparent that a key factor in the low uptake of reusable nappies is that they are simply not on most expectant parents’ radar. The majority of our participants had given little, if any, thought to nappy choices at all throughout the course of the pregnancy. This was because nappies were perceived as something that needed little thought: when a newborn arrives, they would need nappies, and these could be bought as and when needed. Unlike disposable nappies, which are well advertised and are on every supermarket and drugstore shelf, many participants highlighted that they did not know what a cloth or reusable nappy looked like. When reflecting on the points made by individuals with experience using reusables, those that had only ever used disposables mentioned that they did not know what other participants meant by ‘liners’ when talking about the different parts of a modern cloth nappy. Participants with no experience using cloth nappies were unsure about how many cloth nappies would be required as well as the appropriate way to use and clean the cloth nappies properly.

There was a general feeling that there is not enough information available or offered to expectant parents on reusables nappies. Notably, only one participant had used the voucher included in the Scottish Baby Box to claim a free cloth nappy starter set. None of the remaining focus group participants were aware that there was a voucher for reusable nappies included in the baby box. Participants felt that the inclusion of a voucher, particularly amidst a whole host of other leaflets and papers in the baby box, was insufficient as the sole prompt for encouraging expectant parents to try reusable nappies. It was asserted that unless expectant parents had close friends or relatives that supported the use of cloth nappies based on their own experiences, it was unlikely that reusable nappies would be thought of as an alternative to disposable nappies. Additionally, when reflecting on their experiences throughout the course of the pregnancy, all participants recounted that there was no mention of reusable nappies by healthcare professionals such as midwives, nor any visibility of reusable nappies in healthcare spaces such as posters in waiting rooms or samples in maternity wards.

Participants noted a lack of external messaging on cloth nappies and there was a general consensus that there were rarely any online or television advertisements for cloth nappies. While two participants had seen reusable nappies available from large mainstream stores such as Boots and Lidl, the majority of the focus group participants highlighted the lack of visibility of reusables in supermarkets as a barrier to uptake, as many people purchase nappies as part of their regular shop. Participants made a variety of suggestions on how to improve the messaging and awareness about reusables, as noted later in the report (section 5.3).

4.4.2 Cost

As mentioned earlier, cost was cited by participants as both a motivator and a barrier to the uptake of reusable nappies. The initial outlay for a set of reusable nappies was mentioned as a potential barrier, although since many of our participants had simply not considered purchasing reusables this was not a major topic of discussion. For example, when prompted to discuss their thoughts on the purchase of a set of reusable nappies and liners in advance of their child being born, compared to their regular disposable nappy purchasing decisions, one participant explained:

“I do remember looking at them and thinking they were quite expensive for something that you might end up then actually throwing out. And I didn’t know how many you would need. How many do you need to have a supply of nappies for a few days…Do you need 20, 30, 40? And if each nappy is a tenner that’s like hundreds of pounds. Which you probably are going to spend more than that over the course of your child’s nappy time, but to then buy that all in one go? If somebody said to you, you can buy all of these nappies but it’s going to cost you £300, you’re not going to do that when you could buy a packet of nappies for a fiver every so often, every other day or every few days.” (Focus Group Participant)

Additionally, given the current cost of living crisis and the high energy costs, there was a common perception among participants that it would be cheaper to buy disposables overall rather than regularly washing and drying cloth nappies. The majority of participants with experience using cloth nappies were air-drying their nappies, and so perceived environmental and financial costs were less around the tumble drying of nappies and more around the fact that the central heating might need to be on more in order to dry nappies when the weather was not favourable. One participant did use the tumble-dryer to ‘finish off’ the thicker inserts to ensure that they were completely dry.

4.4.3 Time, labour & hygiene

Related to the perceived costs of laundering cloth nappies, participants suggested that reusable nappies seemed like more work than disposables. A number of participants asserted that they simply would not have the time to add the related steps necessary to use and launder cloth nappies to their already busy schedule with a newborn, and that doing so might add additional stress to their lives as parents. This was supported by one participant’s experience; this was the sole participant who had used the baby box voucher, and did try the reusables briefly, but reported becoming overwhelmed and unable to keep up with the washing. Another participant reflected on the perceived added labour of cloth nappies, stating that “it sounds selfish because you’re trying to do something out of easiness and convenience for you, whereas it probably is comfier for the child to have a cloth nappy on” (Focus Group Participant). Furthermore, in contrast to the ‘stay factors’ identified by Pendry et al. (2012), focus group participants who had used reusables with their first child seldom used them with their second or third, citing the convenience of disposables and having more to do in general with multiple children to care for as reasons (as found by Askins and Bulkeley 2005). Across the focus groups reusable nappies were generally viewed as less hygienic than disposables, especially under particularly messy instances with young children:

“there are some times when my kids have done a poonami, if you want to call it, and I would put the clothes in the bin. So then am I going to be putting reusable nappies in the bin rather than washing them? Because sometimes the clothes couldn’t even be saved” (Focus Group Participant).

Dealing with faeces itself was seen as a barrier, and even amongst users of cloth nappies some had adopted the habit of switching to a disposable when they expected the child to soil the nappy with faeces rather than urine alone. Some participants went as far as to state that a cloth nappy becomes “disposable” when soiled by faeces. Additionally, participants were concerned that they would not be able to get the nappies clean enough after use and did not want to put potentially unclean cloth nappies on their children. This hygiene concern extended towards the washing machine and the feeling that washing nappies at home “made a mess of the machine”.

Hygiene concerns were also highlighted in the discussions around second-hand reusable nappies as a means to minimising the high initial financial cost of reusables. There was little appetite for buying second hand nappies (although one participant had done this), with many participants expressing disgust at the thought of using another child’s nappies on their own. As one participant explained:

“I don’t know if I would want to use a second-hand nappy… Obviously these other children have done the toilet in that and I just don't know if I would want to put that on my child”.

Other participants agreed with this sentiment and stated that if a second-hand nappy had a stain on it, they would consider simply throwing it away. The participants were introduced to the idea of nappy libraries and nappy laundering services in response to these concerns about hygiene and labour, however as explained later in the report these services had mixed response perhaps because participants were hypothetically willing to have their reusable nappies passed on to others as second-hand nappies, but were generally not willing to use second-hand or ‘used’ nappies themselves.

Contact

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback