Social care - defining, evidencing and improving: mixed-methods qualitative study

Findings from a mixed-methods qualitative study, that used interviews and creative research workshops, and developed a model (based on the 3Rs of respectful, responsive and relational) that explains how ‘good’ social care in Scotland can be defined, evidenced and improved.

6. Findings

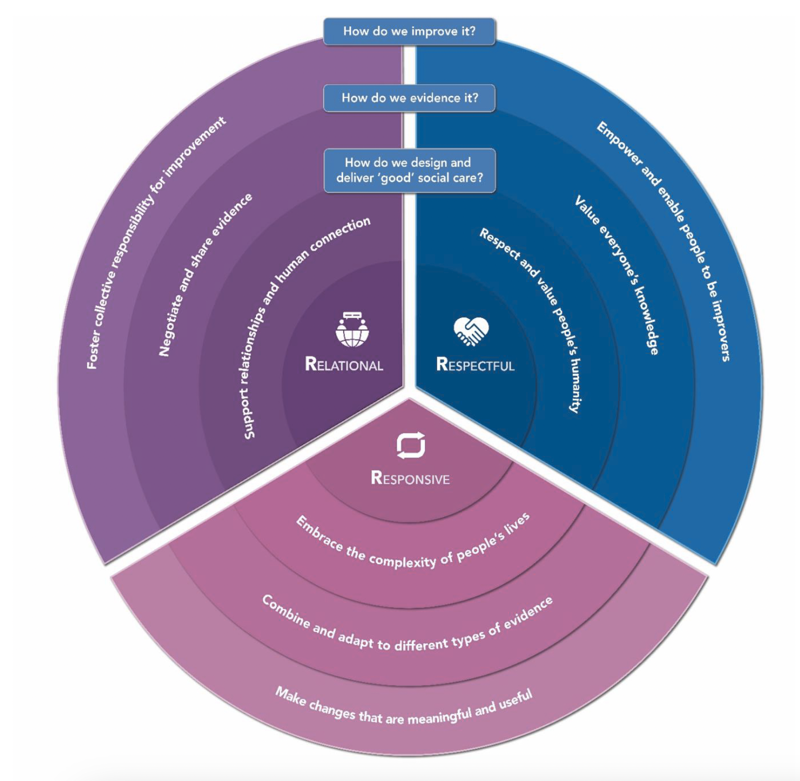

The findings from the combined data analysis of interview and workshop data are synthesised in the "3Rs" model presented below visually in in Figure 1, and the table alternative (Table 2), and summarised narratively thereafter.

6.1 The "3Rs" of delivering, evidencing and improving social care

Respectful |

Responsive |

Relational |

|

|---|---|---|---|

How do we design and deliver good social care? |

Respect and value people's humanity |

Embrace the complexity of people's lives |

Support relationships and human connection |

How do we evidence it? |

Value everyone's knowledge |

Combine and adapt to different types of evidence |

Negotiate and share evidence |

How do we improve it? |

Empower and enable people to be improvers |

Make changes that are meaningful and useful |

Foster collective responsibility for improvement |

Broadly, participants identified the role of social care in society as enabling people to live their lives how they want to and helping them to feel connected to people, communities and environments. The combined interview and workshop data generated three core characteristics that define 'good' social care: respectful; responsive; relational. These three characteristics relate to the experiences of both users and providers of social care and are described below:

Respectful – we recognise that care, evidence and improvement are all founded on an unwavering respect for humanity and the personhood of people using and providing social care;

Responsive – we recognise that care, evidence and improvement all require flexibility and responsiveness to complexity, individuality and change;

Relational – we recognise that care, evidence and improvement all take place within multi-directional relationships.

Defining what good social care looks like, from the perspectives of people in the sector, can provide a foundational structure to inform how social care is designed and delivered. Defining 'good' social care can also provide an anchor for how we approach evidence and improvement. In Table 2 the columns show the defining characteristics of good social care (respectful, responsive and relational) and the rows demonstrate how this definition can be operationalised in how we design and deliver good social care (row 1), how we evidence it (row 2) and how it is improved (row 3). Figure 1 presents a picture alternative. As such, the central (first) circle of the "3Rs" model provides the defining characteristics of 'good' social care, with each outward layer demonstrating how this definition can be operationalised in how we design and deliver good social care (second circle), how we evidence it (third circle), and how it is improved (fourth circle).

The "3Rs" model can be used by focusing on one particular process at a time (delivering, evidencing or improving). Alternatively, or additionally, it can be interpreted by considering each segment in turn to help focus on how each of the core characteristics can be operationalised across social care (delivering, evidencing and improving). The presentation of findings that follows takes the latter approach, providing a detailed account from the research data of how the "3Rs" permeate each layer of delivering, evidencing and improving social care.

6.2 Respectful social care

A summary of a respectful approach to defining, evidencing and improving social care is presented in Tables 3 and 4 below, with detailed findings and illustrative quotes presented narratively thereafter.

Respectful |

Responsive |

Relational |

|

|---|---|---|---|

How do we design and deliver good social care? |

Respect and value people's humanity |

Embrace the complexity of people's lives |

Support relationships and human connection |

How do we evidence it? |

Value everyone's knowledge |

Combine and adapt to different types of evidence |

Negotiate and share evidence |

How do we improve it? |

Empower and enable people to be improvers |

Make changes that are meaningful and useful |

Foster collective responsibility for improvement |

Table 4: A respectful approach to defining, evidencing, and improving social care

For both user and providers, respectful social care:

- Fosters self-identity, self-worth and enables people to feel like their 'true self'.

- Stimulates people's minds, and creates opportunities to gain, regain and maintain skills, regardless of their stage in life or level of impairment.

- Encourages creativity and risk taking.

- Enables people to experience purpose and meaning in life.

A respectful approach to evidencing social care:

- Focuses on knowledge equity, where everyone's knowledge is heard and valued.

- Values social care knowledge as credible and trustworthy.

- Seeks out good practice and experiences as well as negative.

A respectful approach to improvement in social care:

- Involves social care users and providers as trusted experts.

- Encourages creative solutions.

- Invests in staff development because of their intrinsic value and worth.

6.2.1 A respectful approach to designing and delivering good social care.

Fundamentally, 'good' social care respects and values people. All participants emphasised the importance of designing and delivering social care in a way that recognises personhood and humanity. They called for seeing the person "as a human being and not just as a resident or a patient or whatever, but a person" (interview participant 017). Participants highlighted the role of social care in helping people to feel like "their true self" (workshop participant) and enabling people to do what they "want to fulfil in their lives" (interview participant 001). Workshop participants generated several key concepts to define 'good' care, including helping people to experience purpose, meaning, self-worth and growth. Workshop participants with experience of using social care said they wanted "empathy and understanding" and to feel "supported to make the right decisions" for them. Interview participant 019 similarly reflected on the importance of working "with the person on what's important to them". In enabling people to make choices about their lives, participants emphasised that 'good' social care requires a balance between keeping people safe without prohibiting them from engaging in the activities they want to do. As interview participant 005 reflected, "there has to be a certain amount of risk taken" when respecting people's individuality and autonomy, and in enabling their choices to be realised.

In addition to the personhood and humanity of people using social care, participants highlighted the importance of designing and delivering social care in a way respects the people who provide it. Participants cautioned against dehumanising the social care workforce – something they felt had occurred during the recent Covid-19 pandemic – and instead emphasised their common humanity: "we're all human beings" (workshop participant). Both interview and workshop participants highlighted that people working in social care need to feel valued, respected and nurtured in their job – with sufficient access to opportunities and resources to provide 'good' care. As interview participant 019 said, "it has to be a good environment that provides the necessary resources that they need in order for them to do the job that they want to do". Similarly, interview participant 015 reflected, "when there's a person-centred approach to the staff, actually recognising the staff as people… they'll stay longer". Interview participant 014 also emphasised the importance of "appreciating [social care] staff for the skills that they bring… it's just about how we work together and how we think about each other and respect each other's roles". The concepts summarised in Table 4 – and indeed throughout the 3Rs model – therefore relate both to users and providers of social care and highlight the centrality of respect for everyone when designing, delivering, evidencing and improving services.

6.2.2 A respectfulapproach to evidencing social care

A respectful approach to evidencing social care recognises the credibility of social care knowledge and seeks to uphold knowledge equity, whereby everyone's knowledge is heard and valued. Participants across all groups at both workshops said they experienced a lack of respect for their social care knowledge. Sixteen out of the 20 interview participants said they were aware of, or had experienced, knowledge inequity in social care. This was often in relation to a tension between health and social care knowledge, where participants felt that health knowledge was portrayed as superior or more credible. Interview participants provided examples of this occurring in daily practice, for example, having health professionals question whether their calls to NHS24 were "worthy" (interview participant 018). They described having the credibility of their social care knowledge questioned as part of policy consultation processes, as interview participant 009 recalled, "every time we said something or every time we shared something in that space, it sometimes felt as if people went, 'oh! Oh my goodness, care homes do know what they're talking about'… It was almost like they didn't believe us". Participants expressed frustration at the "villainising" (workshop participants) of social care workers and the portrayal of social care users as a "drain" on the much-valued NHS; views that they believed were unhelpfully perpetrated by the media. As interview participant 016 reflected, "this assumption that health is best and knows better [has] been reinforced through the pandemic… We need to be seen on an equal basis… but the media play out bad care, bad person". As a result, participants expressed a general feeling that social care knowledge is devalued in society, policy and practice.

Contributing to this, both workshop and interview participants reported feeling that the current system of regulation and scrutiny in social care[1] was biased towards looking for and reporting on poor practice, rather than evidencing 'good' social care. By contrast, participants reflected on how encouraging and supportive it felt to be asked for 'good' practice examples. Recalling the invite to submit good practice examples for the Healthcare Framework, interview participant 005 reflected: "they put out a shout and asked services can you give us examples of good practice, and again that was a good thing to do because you know during the pandemic there's been a lot of focus on the poor practice." On a practical level, however, participants noted the challenges of making 'good' practice evidence visible. Participants said they felt that too much of the onus is on social care to "put forward" (interview participant 006) evidence, which, as interview participant 009 describes, takes "time, effort and energy" from the provider. As interview participant 010 reflected, "it is really hard because on the whole people are so busy just doing their job that - it's a bit like awards. Who puts themselves forward for awards? It's the usual suspects that have got time to write these submissions".

Both interview and workshop participants felt there was a greater role to be played in the regulatory process to feed information about 'good' practice up to policy teams. Interview participant 010 described how this does happen already in some cases, "we've got a few inspectors that when they come back from an inspection will say, "Just been out there, fantastic work. You need to follow up on that. Let's showcase that. Let's show what they're doing." Both interview and workshop participants highlighted that they felt the inspection process could better raise awareness of good practice nationally, take some of the data collection and evidence sharing burden from frontline social care providers and help the scrutiny process to feel more supportive rather than punitive. However, in the workshops some participants talked about their negative experiences of sharing evidence of 'good' care with inspectors because their trustworthiness was called into question. Recalling their experiences of sharing user-feedback data with inspectors, one workshop participant said, "if someone says they are happy, they [the inspectors] don't trust this". As a result, participants highlighted how fears of being dismissed impacted on their willingness to share good practice examples, even when asked. As interview participant 007 noted, "it makes it hard for people to speak out and go, "Look, I'm doing this, this is great" and not face other people telling them off or telling them what they think based on their kind of backgrounds and perspectives." Similarly, interview participant 013 said, "we've all got things that we're doing better and things that we're doing worse. And I think the vulnerability in many respects is … if you raise your head above the parapet to say, "Look at this amazing thing that we've done." Then people will say, "Yes look at that amazing thing but what about this? It's terrible, it's dreadful."

6.2.3 A respectful approach to improving social care

A respectful approach to improving social care is about valuing the knowledge and evidence that people bring to the improvement process. Participants reflected that, when they feel that their knowledge is trusted and valued, they feel empowered to improve. Conversely, when they feel that their knowledge and the evidence they provide are called into question – or when negative evidence is privileged over the positive – they feel demoralised. Within this broad experience of knowledge inequity, it is possible that social care staff are so used to negative experiences of scrutiny that it deters them from coming forward to evidence and improve services. As one workshop participant described, "sometimes it feels like providers are afraid to make a mistake or to take a chance, they are afraid of being criticised". Interview participant 008 similarly commented, "we are making ourselves visible and vulnerable by sharing what we do… well what if they turn around and say, "it's not good enough?... we should be considered experts, but we're put in forums where we don't feel like experts." Disrespecting the knowledge, credibility and capability of social care staff and users is therefore the antithesis to improvement; it paralyses rather than encourages change. As workshop participants described, the fear of "doing things wrong" or being "punished" often prohibits creativity and risk-taking for improvement. Interview participant 013 identified similar challenges, calling for a more respectful approach to improvement: "you can have the stick and carrot change. And we're seeing a lot of stick and carrot… and you can achieve results in that way and we see that and we see that frequently. Or you have sustainable long-term change where you've redesigned your system, you've taken people along with you and people are truly doing something different."

As part of a more respectful approach to social care improvement, several participants called for greater investment in staff development by building their capacity and capability to engage in quality improvement, research, evaluation and service design work as in integral part of their jobs. As one workshop participant reflected, "we have a once in a lifetime opportunity to really create a social care system which has parity with the NHS in relation to workforce, fair pay, fair work and more important, produces really positive outcomes for everybody". As interview participant 006 suggested, social care staff need to feel "happy, content, motivated" with access to good leadership and the opportunity to ask questions, challenge the status quo and be involved in leading change. Importantly, as reflected by workshop participants, the motivation for investing in social care staff development is not about seeing them as a means to an end, but fundamentally valuing them as credible, valuable knowers who need opportunities to grow, learn and experience joy in their jobs. It is only in this way, where people are respected and empowered to be improvers, that social care becomes "self-sufficient in sustaining that improvement" (interview participant 016).

6.3 Responsive social care

A responsive approach to defining, evidencing and improving social care is summarised in Tables 5 and 6 below, with detailed findings and illustrative quotes presented narratively thereafter.

Respectful |

Responsive |

Relational |

|

|---|---|---|---|

How do we design and deliver good social care? |

Respect and value people's humanity |

Embrace the complexity of people's lives |

Support relationships and human connection |

How do we evidence it? |

Value everyone's knowledge |

Combine and adapt to different types of evidence |

Negotiate and share evidence |

How do we improve it? |

Empower and enable people to be improvers |

Make changes that are meaningful and useful |

Foster collective responsibility for improvement |

Table 6: A responsive approach to defining, evidencing and improving social care

For both users and providers, responsive social care:

- Creates genuine options, respects freedom of choice and enables people to make decisions.

- Respects that people change over time and situates care within the broad context of people's past, present, and future lives.

- Listens deeply to individuals, not based on stereotypes, preconceptions or rigidly standardised approaches.

- Enables access to satisfying, enjoyable and nutritious meals.

- Is provided at the time and place it is needed, as opposed to being determined by systems, rotas and available resources.

A responsive approach to evidencing social care:

- Embraces messiness and values qualitative evidence.

- Brings together different types and combinations of evidence at different times, in different ways.

- Works to a flexible evidence plan rather than fixed benchmarks.

- Invests dedicated resource into developing and implementing a flexible evidence plan, with a clear process for reflecting regularly on the continued usefulness and sensitivity of the evidence approach.

A responsive approach to improvement in social care:

- Designs, implements, evaluates and refines change in response to what is meaningful and useful to social care users and providers.

- Uses and adapts methods flexibly to include social care staff and users as active agents in improvement.

6.3.1 A responsive approach to designing and delivering good social care

'Good' social care is responsive to people's individuality and embraces and adapts to the complexity of people's lives. Interview participant 018 described responsive social care as "making sure [service users] get the right care by the right people at the right time and have that choice". Similarly, interview participant 008 reflected on the need to provide responsive care tailored to the outcomes "desired by the service user, not by protocol, policy, or regulation". Workshop participants emphasised the need to provide social care at the time and place it is needed, as opposed to being determined by systems, rotas and available resources. As one workshop participant described, 'good' social care is not "focussed on the system or the system's needs, instead it is focussed on the person's needs". A responsive approach to designing and delivering 'good' social care therefore requires "listening deeply" (workshop participant) to individuals rather than arriving at decisions based on stereotypes, preconceptions or rigidly standardised approaches. Participants talked about seeing people within the whole context of their lives, not just "distilled down to the condition that they experience or the service they use" (workshop participant). Participants also identified that individual needs and preferences change over time, and so social care should be situated within the broad temporal context of people's past, present and future lives: "where we come from, where we are and where we are going" (workshop participant). Participants also emphasised the need to give people "genuine options" that can be supported and actualised (workshop participant).

6.3.2 A responsive approach to evidencing social care

Responsive social care, that meets people's changing needs, preferences, and contexts, requires an equally responsive approach to evidence. All participants, across both workshops and interviews, agreed that 'good' social care is best judged by the people experiencing and delivering it. Many called for greater use of qualitative data when determining what 'good' social care looks like and whether it has been achieved. Participants felt that services were judged predominantly on numerical data about care delivery (for example statistics around delayed discharge and care home beds) rather than qualitative feedback from users and staff about care experience and satisfaction. They felt that a lot of the evidence for what makes 'good' social care is found in "the small moments" (workshop participant) and everyday demonstrations of warmth, empathy and kindness that cannot be captured quantitatively. This was echoed in the interview data, with participant 018 suggesting that "it would be easy to measure how much your beds were filled... but it's very hard to measure the quality of the little moments that you don't always see". Whilst there was consensus around the need for more qualitative data, some participants were uncertain about the extent to which Scottish Government were interested in qualitative evidence and others raised concerns about the extra workload to facilitate qualitative data collection: "the last thing the sector needed was more kind of questionnaires going out to them and focus groups" (interview participant 010).

A responsive approach to evidencing social care involves exploring the degree of fit between the individual and the care they receive. Participants all viewed 'good' social care as a subjective concept, emphasising the importance of listening to "the voice of the individual… and their agreement that the outcomes they are achieving equal good social care" (workshop participant). Interview participant 008 similarly commented, "what does good practice look like? I think it is meeting outcomes that the person wants, and it's that warm feeling that your values are aligned with the values of the person receiving care". Both workshop and interview participants advocated for accepting and embracing "messiness" in evidencing social care, rather than fighting against it. This entails a high degree of complexity and responsiveness in how we evidence what 'good' social care looks like. People's perceptions of 'good' may change over time; their preferences do not remain stable, and their past preferences may be different to their current ones. Perceptions of 'good' also vary from one person to another, as one workshop participant reflected, "when we say defining what is good care, that is very individualised… what I define as good is not going to be an intersection for everybody". As such, participants raised concerns that using a single "generic" measure of 'good' care for everyone could risk "huge blind spots and individual needs are missed" (workshop participants). Rather than identifying a fixed, standardised benchmark for what 'good' social care looks like, participants therefore called for a responsive approach that brings together different types and combinations of evidence, at different times and in different contexts.

Workshop participants suggested that there could be a dedicated evidence plan for the NCS. They recommended developing a clear and specific plan for "how evidence will be generated and accessed, what will be included as evidence, how it will be assessed, how it will be used, and who will contribute to it" (workshop participant). This would involve judicious decisions about when to generate new data as well as how to use and employ existing data. Interview participants also suggested planning for evaluation and monitoring in tandem with policy development, so that policy makers can be responsive to new evidence throughout the design and implementation phases of policy, not just during the evaluation phase. As interview participant 002 stated, "we want to be at the forefront on what's going on… if you don't have the evidence to back it [policy] up… it will hold little value". Several participants, however, perceived that effort and resources were focussed primarily on getting policy written and published, with was less time to focus on implementation and evaluation planning. Participants therefore called for dedicated and ongoing investment of finance and resource in building, sustaining, and using a responsive evidence base for social care. Moreover, rather than devising and implementing a one-off evidence plan, participants suggested regular review and reflection on the usefulness and sensitivity of the evidence approach in action.

As part of a responsive evidence plan, participants felt that effective evidence generation and analysis mechanisms needed to be in place. Many reflected on the need to redress deficits in the current evidence base for social care, sharing frustrations at having an incomplete demographic profile of service users or contemporary workforce statistics. Interview participant 013 reflected on the inconsistencies in social care evidence, saying "we have a [paucity] of data in some areas… a surfeit of data in others, we have inconsistent analysis of the data". Interview participant 006 reflected on the gaps in published research on social care, providing examples of care home improvement projects they knew had taken place but could not find published evidence for: "when I've searched literature I'm not finding anything around these pieces of work, so, you question the existence". From a social care provider perspective, interview participant 016 highlighted the lack of support and opportunity to contribute formally to the evidence base saying, "you could be doing a piece of improvement work in a care home and one of the things that we're not brilliant at… is actually writing that up and evidencing it". As such, participants identified a need for capacity and capability building in the social care sector and for greater equity between the systems underpinning evidence-informed health and social care. Participants referenced examples such as Healthcare Improvement Scotland, the Scottish Patient Safety Programme, the King's Fund and other think tanks, calling for similar structures in social care to help strengthen the evidence base and cultivate a sustainable, responsive evidence-informed culture.

6.3.3 A responsive approach to improving social care

A responsive approach to improvement means ensuring that changes are designed, implemented, evaluated and refined in response to what is meaningful and useful to social care users and providers. All participants said that the core purpose of social care improvement was "to make life better for the individual" (workshop participant). There was agreement that improvement activity should focus on "what matters to the person" (workshop participant) and "should be based around the needs of the individual" (interview participant 004). Although they welcomed the idea of a national approach to improvement, participants emphasised that this had to be assimilated flexibly and responsively by local people and in local contexts. As one workshop participant described, "a national and proven approach would be one that kind of integrates this idea of complex systems, except that there is no kind of linear process for improving that can fix everything at once". Other workshop participants cautioned against "doing improvement for improvement's sake" and suggested that a national approach should have an in-built recognition that "what's important to the person… may not be the same as what's important to the system". All participants agreed that social care users had a critical role in identifying when improvements were needed and providing insights into how social care could be better, calling for them to have "the loudest voice and the power to effect change" (workshop participant).

Responsive improvement involves a combination of learning from evidence of what works elsewhere, whilst simultaneously being sensitive to local need, context and difference. Interview participant 010, for example, reflected on the need to time improvements responsively, saying: "it's certainly hard to be innovative in times of crisis and when the conditions for change are far, far removed from optimal." Interview participant 013 expressed some frustration at prior experiences of social care improvement where "people get told to do something, which we don't know why it worked somewhere else… and what happens in Wishaw isn't necessarily transferable to what happens in Orkney". Interview participant 006 cautioned against imposing innovations and benchmarks un-critically from one setting to another, saying it could "potentially have an adverse impact on [social care providers'] motivation to improve because they could constantly feel like they're just not achieving". Moreover, interview participant 004 reflected on the need to ensure that improvements are "equitable… [for] people of you know different socio-economic backgrounds, different gender, so I'd want to ensure that whatever the good practice is applicable to the greatest number of people". A responsive approach, where improvements are tailored to what is meaningful and useful to different individuals and local contexts, is therefore also essential to successful change that can address inequities in outcome and experience for different people using social care in different parts of Scotland.

The active involvement of people working in social care is crucial for responsive improvement. They hold uniquely valuable knowledge about contextual conditions and are well placed to inform decisions about what, when and how to improve. Participants talked about how factors such as organisational readiness, staff capacity and resource, and current levels of improvement activity and experience all need to be taken into consideration. Interview participant 006 reflected that, "not everyone will need the same level of input" to lead and implement improvement in their setting. In visioning a distinctly social care approach to improvement, workshop participants suggested that existing improvement methodology needed to be adapted flexibly and reflexively to suit the social care setting. Some participants felt that the language and organising structures of improvement methodology (e.g. models, frameworks and data tools) could be "exclusionary" (workshop participant) and "elitist" (interview participant 006). One workshop participant called for improvement to be "decolonised", making it more accessible, useful and understandable for people in social care. There was a perception that the discourse around improvement is dominated by healthcare, with interview participant 008 reflecting "we [social care providers] have lots to say, but we also are very intimidated when people are using long words and talking about healthcare systems… it's a language we don't know". Participants also reflected that, whilst it can be helpful to learn from health initiatives, it was preferable to champion social care success stories as this would be more motivating, encouraging and acceptable to social care staff.

6.4 Relational social care

A relational approach to defining, evidencing and improving social care is summarised in Tables 7 and 8 below, with detailed findings and illustrative quotes presented narratively thereafter.

Respectful |

Responsive |

Relational |

|

|---|---|---|---|

How do we design and deliver good social care? |

Respect and value people's humanity |

Embrace the complexity of people's lives |

Support relationships and human connection |

How do we evidence it? |

Value everyone's knowledge |

Combine and adapt to different types of evidence |

Negotiate and share evidence |

How do we improve it? |

Empower and enable people to be improvers |

Make changes that are meaningful and useful |

Foster collective responsibility for improvement |

Table 8: A relational approach to defining, evidencing and improving social care

For both users and providers, relational social care:

- Takes place in the context of trusting, empathic, personal, respectful and familiar relationships.

- Connects people with other human beings and creates a sense of belonging, where people are valued for who they are and what they bring to communities.

- Harnesses technology in flexible and strategic ways so that it supports and enables human connection, rather than replaces it.

- Involves being with people and facing difficult situations and emotions together'.

- Means having accountability and repairing relationships when they go wrong.

- Is holistic, focussed not only on the individual in isolation but their interconnected relationships with family, communities and systems.

A relational approach to evidencing social care:

- Recognises that evidence is not singular or static, but in continual negotiation.

- Does not singularly privilege one perspective of evidence over another e.g. what counts as evidence for regulatory bodies might be different for to what matters to users and providers.

- Uses inclusive and creative ways of generating data.

- Is based on transparent and accountable sharing of data for everyone's benefit.

A relational approach to improvement in social care:

- Embeds improvement in daily practices and conversations as a 'way of life'.

- Builds and sustains a network of improvers with established mechanisms for sharing and learning.

- Fosters care literacy in society to encourage everyone to support and contribute to social care improvement.

6.4.1 A relational approach to designing and delivering good social care

A relational approach to designing and delivering 'good' social care means supporting relationships and human connection. Both interview and workshop participants highlighted the key role that social care plays in connecting people with other human beings and "creating a sense of belonging" (interview participant 005), where people are valued for who they are and what they bring to communities. A key aspect of designing and delivering social care in a relational way is to focus not on the individual in isolation but their interconnected relationships with family, communities and systems. As described by one workshop participant, a relational approach means that "we don't atomise individual people, but we actually recognise the value of people in relationships". This requires "involving the family" (interview participant 005) and using technology in flexible and strategic ways so that it supports and enables human connection, without "missing out on human interaction and relationships" (workshop participant).

Participants commonly used terms such as trusting, empathic, personal and respectful to characterise the relationships between the people using and providing 'good' social care. One interview participant (019) described their role as a social care provider as "caring from the heart". Another interview participant (008) described 'good' social care as being driven by a values-based workforce who prioritise and nurture strong relationships with the people they support. They said, "find those value-strong people and we can train them. Because all you're doing is adding things… some training, legislation… policy…protocol". Workshop participants similarly talked about the personal, familiar and human connection between social care staff and users, emphasising the need for "being with people and facing difficult situations and emotions together", "having accountability", and "repairing relationships when they go wrong".

6.4.2 A relational approach to evidencing social care

A relational approach to evidencing social care recognises that evidence is not singular or static but is in continual negotiation. Different people have different perceptions of what constitutes evidence of 'good' social care. They also have different standards for judging the quality and trustworthiness of the evidence available, impacting on how they choose to interpret and apply it. For example, workshop participants suggested that what counts as evidence of good social care for regulatory bodies might be different to what matters to social care users and providers. Reflecting on the 'good' practice submissions sought as part of the Healthcare Framework development, interview participants gave several differing accounts of how they understood and interpreted submitted evidence. Some prioritised providing a fair picture of the sector, as interview participant 004 explained, "the people that sent these examples to us believed they were good practice, so we accepted that at face value. We were careful however not to say that they were best practice, because… there might be other examples… we hadn't heard about." Several others emphasised the importance of situating evidence in the wider context of a service, such as interview participant 010 who wanted to be a "little bit careful that they weren't promoting services for good practice that were actually going through large scale investigations…because that could be particularly distressing for families." Other interview participants reflected on how context shapes what people accept as evidence of 'good' social care, with interview participant 012 saying, "what somebody thinks is innovative, other places might be doing as routine".

Rather than privileging one perspective on evidence over another, participants stressed the importance of embracing flexibility when seeking, evaluating and accepting evidence of 'good' care. As one workshop participant said, "there should be equal opportunities for our differences and for different types of knowing and different types of knowledge". Another argued that different types of evidence need to be "intertwined in a way that has good outcomes for everybody". Participants said they felt this was best achieved through closer relationships between the people generating, evaluating and using evidence for social care. Participants working in social care described wanting to feel closer to policymakers, both to showcase their work and to give decision makers access to intangible sources of evidence: "if you've worked in care homes… you know when you walk into a care home whether it's good or whether it's not. You can walk through the door, and you can already tell, right? So how many of those policymakers have ever crossed the threshold of a care home to know whether it's good or whether it's not?" (interview participant 009). Participants working in policy shared a similar enthusiasm for regular and ongoing engagement with professionals working in the social care sector. Policy makers felt by doing so they could better understand the work being undertaken across the sector which would allow them to inform policy decisions now and in the future.

Participants suggested that building meaningful and ongoing relationships could help to unearth otherwise hidden evidence. Despite an open invitation to submit 'good' practice examples during the Healthcare Frameworkengagement, many interview participants identified barriers to responding. Some participants expressed a lack of confidence and self-recognition, with interview participant 018 saying "we don't think we do anything differently to what other people do" and interview participant 003 saying, social care providers "don't necessarily consider it as being good practice, it's just… that's what we do". Other participants expressed a lack of trust that the evidence they put forward would be welcomed and used. Both workshop and interview participants suggested that the Scottish Government could be more transparent and accountable in relation to how evidence is used to inform policy decisions. One workshop participant asked for "real responsive feedback loops. If you ask for someone's voice, how do we make sure that we've gone back to them and shown how that has contributed? Or if there's a valid and practical reason why that cannot be incorporated? People need to know". Similarly, interview participant 008 said, "the people within our sector are interactional… the buzz people get if they get an email back saying, "thank you for submitting that form, you made an interesting point about so and so, thank you for doing that." Just that single line would be enough… but it's something which, I'm kind of hitting on a nerve because it just never happens."

So, whilst there is evidence of a clear will for closer communication between policy and practice, the data suggests that relationships are not always cultivated in a way that supports meaningful negotiation of evidence. Participants felt that the nature of existing consultation models and data collection processes could exclude certain groups from negotiations around what counts as evidence for good social care. They criticised existing methods for requiring people to communicate in ways that are "understandable to us" (workshop participant) rather than adapting data generation approaches to fit within their unique cultural, linguistic and knowledge contexts. A workshop participant with lived experience of using social care reflected that "when we are taking part in events and workshops and meetings… communication needs to improve quite a bit", suggesting that the language of current consultation processes needs to be more inclusive. Participants called for more relational and inclusive methods for generating evidence, including "shifting spaces to make room for everyone" and finding "different ways of consulting. We can't just assume that one size fits all". Interview participant 009 suggested that visual methods, for example, might support more inclusive conversation, because they invite a diversity of opinion: "these things should be a dialogue… if you look at it and I look at it we'll all look at it, we'll all see something different."

6.4.3 A relational approach to improving social care

A relational approach to improvement involves collaborative relationships between the people using, delivering, designing, evaluating, and overseeing social care. As one workshop participant suggested, "whatever the system looks like in terms of improvement, it will be led by people and relationships". Workshop participants said they wanted improvement to be enacted through open, ongoing, and reflective dialogue, embedded in daily practice as "a way of life". They envisioned a national approach to improvement that was less about directing what should be improved and how, and more about establishing and maintaining functional and accessible mechanisms for sharing learning across the sector. Workshop participants suggested that this could involve a network of active communities, each working to improve care locally and responsively whilst simultaneously sharing and connecting outwardly across the network. Some participants expressed a frustration around common misconceptions that "competitiveness", particularly between private social care providers, was an immovable barrier to sharing evidence for improvement. Instead, they felt that, particularly following the COVID-19 pandemic, they were "all in this together" (workshop participant) and the climate was one of openness and willingness to share and learn. Interview participant 008 similarly felt that the sector was, "working together in a way we never have before, so we are more cohesive. Information flows like it's never flown before, there is a swell of wanting more, improved relations, improved everything".

Participants suggested that sharing evidence of 'good' social care could catalyse and model improvement across the sector. Interview participant 002 hoped that sharing 'good' practice examples would showcase "what could be done differently to achieve outcomes that are positive", whilst interview participant 016 suggested, "the more we see of the good, that will spread". Participants were all very clear, however, that the purpose of sharing 'good' practice was about inspiring and informing local change, where ideas could be assimilated responsively into each unique context rather than coming down as externally imposed directives from external bodies, such as Scottish Government or regulators. Some participants also reflected on the importance of sharing and learning from negative evidence, including interview participant 013 who said, "I don't think it should ever be perceived as being pejorative, even when people are not doing well, because you could get really effective support when things aren't going as well to improve things". Likewise, interview participant 007 highlighted one of the drawbacks of focussing solely on 'good' practice is that it can obscure the problem areas and hinder effective planning and progress: "if you don't define the problem and you don't say, right, what is it that we're trying to fix? It's then harder to… map that pathway of where you prioritise".

Participants said that publicly championing 'good' social care could be an effective means of increasing its societal value and challenging negative media portrayals. They felt that "some big shifts are required" (workshop participant) in how social care is promoted and perceived, recognising that misconceptions and a bias towards the negative can adversely impact upon meaningful consultation and user-driven improvement. As one workshop participant reflected, "many people using social care may have low expectations based on wider stigma, so how do we ensure consultation is aspirational and sets higher standards for what people deserve?". Participants felt that the Scottish Government could play a helpful role in spreading and promoting evidence of 'good' social care to "give a little bit of extra weight" (interview participant 002), with interview participants 011 and 020 highlighting the different routes already in use to promote 'good' care via blogging, social media and the Scottish Government website. Going even further, workshop participants also called for new initiatives that could "radically overhaul" the societal view of care. These included building "care literacy", "citizenship" and "collective responsibility" right from childhood. Workshop participants imagined an ideal scenario where "the improvement team is absolutely everyone in society. And what happens is from the moment you are born you understand that everyone cares".

Contact

Email: socialresearch@gov.scot

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback