Cost of living - effects on debt: review of emerging evidence

This report considers the evidence on the effects of the cost of living crisis on problem debt in Scotland

3. What types of debt are households experiencing and how has this changed over the cost of living crisis?

In order to fully understand the debt landscape in Scotland it is important to consider the different types of debt that households have. Some but not all debt types are considered, and a graphic of the debt types and sub types included in this report is in Annex 1. While this section is structured according to separate debt types, in reality household debt is complex and debt types are often multiple and interconnected.[24] Many households will also fall in and out of unmanageable debt.

3.1 Energy debt

Despite energy prices falling from their peak in 2022, they remain higher than before the cost of living crisis and those with built up energy debt continue to struggle to pay it off.

A number of sources show that energy debt increased over the cost of living crisis. In autumn 2023 Ofgem reported on record levels of energy debt (£2.6 billion), attributing this to both the rise in wholesale energy prices and wider cost of living pressures.[25] [26] The number of households in debt and arrears in Great Britain (GB) increased by around 20% during 2023, from 1.9 million to 2.3 million, with levels of individual debt increasing at an even faster rate.[27]

Debt advice services show that energy debt is one of the most common forms of debt that they help people with, and that the rising cost of fuel is a key reason for increased demand for their services.[28] [29] [30] Citizens Advice helped more than twice as many adults with energy debt in England and Wales in 2023 than in 2020.[31] Although StepChange data for the UK and Scotland does not show an increase in the proportion of new clients in energy arrears between 2022-23 it does show a significant increase in average amount of energy arrears owed over this period.[32]

Average energy debts – The Resolution Foundation found that the average amount owed by Ofgem customers in arrears on their gas or electricity bill (GB) increased by half (51%) in just over a year between Q2 2022 and Q3 2023.[33] Citizens Advice data (England and Wales) show the average energy debt owed in 2023 was over £1,840, a 21% increase since 2022.[34] The average energy related debt brought to Citizens Advice Scotland in 2023/23 was around £2300 but this rose to around £3000 for clients in remote and rural areas.[35] StepChange Scotland data shows that between 2022-23 the average amount owed on utility bills was £1,960 for dual fuel arrears (up from £1,623), £1,266 for gas (up from £847) and £1,886 for electricity (up from £1,438).[36] In 2024 Ofgem estimated average debts were £851 for those with a repayment plan and £1,761 for those without.[37]

The proportion of new StepChange Scotland clients in difficulty with dual fuel energy arrears increased from 46% to 50%.[38] The increase in dual fuel arrears is also reflected in other recent Scottish sources.[39]

“These are staggering increases for clients to absorb, particularly when incomes have increased at a significantly lower rate….”

StepChange, Scotland in the Red (2023)

Many households are struggling with their bills and their energy debt has been rising.[40] [41] The latest Ofgem statistics show that between Q1 2024 and Q2 2024, energy debt and arrears rose by 12%, from £3.31bn to £3.70bn, equating to a 43% increase from Q2 2023.[42] Recent analysis shows that while energy prices have fallen since early 2023, typical bills under the January to March 2025 price cap will be just over 40% higher than in winter 2021/22.[43]

High energy prices particularly affect low income households who are more likely to have outstanding energy debts and who spend proportionately more on energy costs than high income households,[44] making it harder to repay debt.[45] Households on prepayment meters (PPMs) are further affected by high energy prices and have historically been charged more for energy than households who pay by direct debit.[46] PPM customers are also unable to spread the costs over a longer period, pay higher standing charges and are more likely to be in fuel poverty than households paying by other methods. [47] [48]

Consumer Scotland’s latest Energy Affordability tracker study (2024) also shows that despite energy prices having fallen since 2022 and consumers generally finding them more affordable, bills remain high and a significant minority of consumers are struggling to pay their energy bills.[49] [50] It shows that 9% of Scottish consumers are in energy debt, and almost half (48%) of those reported not being confident that they will be able to pay off their energy debt. Around one in six (17%) of those in energy debt had been put on a prepayment meter (PPM) as a result of their energy debt.[51]

Persistent and ‘bad’ energy debt – Consumer Scotland’s research found there had been an increase in the numbers of consumers behind on their bills and facing debt recovery action between the two most recent waves of the survey (October 2023 and January/February 2024). While there was a reduction in informal and credit card /overdraft debt as a form of energy debt, the percentage of respondents in energy debt who are facing debt recovery action doubled from 10% to 20%.[52]

‘the legacy of the crisis continues to affect households in the form of energy debt, built up as a direct result of high energy prices…’ ‘While these findings are based on limited data, an increase in debt recovery action is something that might be expected at this point, as debt built up during the energy crisis and not yet repaid becomes a key issue for suppliers.’ Consumer Scotland (2024)

It is also important to note that energy debt is the only type of ‘private debt’ that can be deducted ‘at source’ from a person's welfare benefit (social security) payments. Aberlour mapped the volume and types of third party deductions (including gas and electricity deductions) by local authority in Scotland as an online resource.[53] Crucially, this practice means the maximum repayment threshold can be extended from 25% of a claimants standard allowance to 40%. The DWP’s response to an FoI request by Aberlour children’s charity stated that: “You may have more than 25% of your Standard Allowance taken off if you pay a ‘last resort deduction’. A ‘last resort deduction’ helps to prevent you from being evicted or having your utilities cut off. It is paid directly to the person or organisation you owe money to.”

Direct deductions from public sector debt is explored in more detail in Section 3.2.2.

3.2 Public sector debt

Public sector debts are debts and arrears to public bodies such as: council tax and rent arrears; school meal debt; social fund loans; child maintenance loans; Universal Credit (UC) advances; DWP loans; benefit sanctions; court fines; and overpaid tax credits. This section summarises the evidence since the start of the cost of living crisis and some, but not all, of these debt types are considered. A detailed review of public debt in Scotland produced by Heriot-Watt University provides a comprehensive assessment and covers the period up to 2022.[54]

Levels of public sector debt are not regulated to the same standards as consumer credit debt, and so are much harder to measure.[55] [56] As Citizens Advice explain: “Unlike financial debts data which are carefully monitored and reported on, the scale of government and bill debts is hidden. Some data is out of date, and some isn’t collected at all.” [57] [58]

Despite this, there is a body of evidence that shows the growth of public sector debt in Scotland and the UK, especially amongst low income households over the past decade. [59] This has been attributed to factors such as austerity, the COVID-19 pandemic and reforms to the benefit system. However, these types of priority debt have also increased sharply over the last 2-3 years as a result of the cost of living crisis and escalating bills. Current estimates are that 6.2 million adults across GB are behind on payments owed to public bodies.[60]

3.2.1 Council Tax debt

Council tax debt was a growing problem before the cost of living crisis, it has long been one of the most common debt types brought to debt advice agencies in Scotland and one of the most ‘challenging’ types of debts,[61] [62] [63] [64] StepChange describe council tax as an enduring and ‘entrenched problem’,[65] while Treanor highlights the ‘unrelenting’ way that debts can accumulate once people fall into arrears.[66] In addition, in Scotland local authorities have 20 years to enforce their debts, rather than five years which applies to unsecured debt. Therefore the statute of limitation (also known as the prescription period) for council tax in Scotland is also 20 years, compared to the equivalent 6 years in England and Wales. This could have been changed under the Prescription Act 2018 but was not, and has also not been changed by the new regulations of 2021.[67]

The Scottish Parliament’s Social Justice and Social Security Committee report on low income and public sector debt in 2022, found that Council Tax arrears in Scotland were a key area of concern for respondents to their call for views, particularly issues around poor communication, rigid payment dates, speed of action taken by local authorities and punitive enforcement approaches through the summary warrant process.[68] The impact of council tax collection practices (and on vulnerable groups) is discussed Section 4.2.

Current estimates of council tax debt – The latest Council Tax Collection Statistics were published in June 2022 and cover the period up to and including the financial year 2021-11, so only up to March 2022.[69] These show that in 2021-22 for Scotland as a whole, the total amount of Council Tax billed (after Council Tax Reduction) was £2.723 billion. Of this total, £2.607 billion, or 95.7%, was collected by 31 March 2022, which is higher than the figure for the previous year (94.8%), which was lower during the pandemic when councils suspended debt recovery process and actions to avoid contributing to financial pressure on Council Tax payers.[70] More recent estimates vary, from 1.3 million UK households being behind on their council tax,[71] to 3.3 million people across GB in arrears with their council tax.[72]

A report by IPPR Scotland for the Robertson Trust (2022) found that over one in ten (12%) of the lowest income households were behind on council tax bills, compared to one in a hundred for the highest income.[73] Analysis of the latest Joseph Rowntree Foundation (JRF) cost of living survey of low income households (2024), shows that 17% of these low income households (197,729) are in arrears with council tax in Scotland.[74]

There is evidence that council tax debt has increased over the cost of living crisis – recent analysis by the Centre for Social Justice (2024) at the UK level shows that while increasingly fewer households report being behind on their council tax compared to 2010/11, the amount those households fall behind on is increasing. The report finds that the cumulative amount owed in arrears to UK local councils has significantly increased, rising from £1.7 billion in 2004/05 to £5.4 billion in 2022/23. Further, it is increasingly low income households who have council tax arrears.[75]

Many debt services report that cases of,[76] and amounts of,[77] [78] [79] council tax debt have increased over recent years,[80] and that cases are becoming more complex.[81] Citizens Advice data for England and Wales (2024) shows the average amount of council tax debt amongst their clients has increased by 36% since before the pandemic.[82] StepChange Scotland’s annual statistics (2023) showed that the proportion of clients with council tax arrears has fallen since 2019, with the average arrears amount the same as 2019.[83] However, tentative evidence from StepChange’s latest quarterly client data (2024) shows that there may have been recent increases in the proportion of clients with council tax arrears and average arrears.[84] The average council tax arrears per client in Scotland rose 11% over the last year and the average amount of council tax debt owed during the second quarter of 2024 was £2,075, an increase of £204 from £1,871 in the second quarter of 2023.[85]

Our clients, particularly those on the lowest incomes continue to struggle to cover their bills each month, with the average amount of debt across essential bills like council tax and energy still rising… We know that council tax in particular is a bill that our clients have struggled with for a number of years, and council tax collection practices are a particular issue – often plunging people into more hardship, rather than helping them to repay.” Sharon Bell, Head of StepChange Scotland, press release, July 2024

3.2.2 Benefit debt

Benefit debt or “direct deductions” are taken at source from social security benefits, and are mostly used by the DWP to (i) recover advance UC payments (e.g. to cover the five-week wait between claiming UC and getting the first payment); (ii) recover overpayments of benefits; (iii) budgeting loans to support with unexpected costs such as household repairs. Other deductions can be taken from a person’s benefits or pay to repay public debts like rent, council tax, court fines and even energy debts (not public debt, explored above). The system is complex and the amount deducted varies according to the type of deduction, but is usually up to 25% of a person’s standard benefits allowance (although legislation allows for 40%). Many people have multiple deductions for different arrears.[86] [87] [88]

The Money and Mental Health Institute (2024) estimate that 1.1 million adults across GB are behind on the repayment of overpaid benefits or tax credits.[89] Citizens Advice (2023) reported that households most affected are those with children, and where someone has at least one long-term health condition or disability.[90]

Direct deductions have increased since the start of the pandemic – there is some evidence that increases in benefit debt may in part be driven by legacy UC advance repayments from over the pandemic, which were not suspended over this period, like other benefit deductions.[91] [92] The Health Foundation (2022) found that in 2021 more than 1 in 10 of the almost 5 million UC claimants had money deducted from their benefits for debt repayments. In 2021, 531,000 UC claimants had at least one withdrawal from these benefits (around 11% of all claimants) and nearly 90,000 had multiple withdrawals.[93]

In 2022, the children’s charity Aberlour published a report on the level of public debt owed by households with children in Scotland in receipt of UC. The report found that more than half (55%) of low income families with children in Scotland in receipt of UC have at least one deduction by DWP from their monthly income to cover debts to public bodies (equating to nearly 80,000 families) and more than a quarter (27%) have multiple deductions. Scotland had a higher proportion of families with multiple deductions from their monthly income by DWP to cover debts to public bodies compared to England and Wales.[94]

In 2023, Citizens Advice reported that 45% of UC claims are subject to a deduction, and over 1 in 5 UC claimants are subject to a deduction of more than 20% of their standard allowance.[95] A separate UK poll for Citizens Advice in 2023 showed that debt arising from tax credit and benefits overpayments combined increased 24% since 2019.[96]

Evidence on the effects of direct deductions - deductions can reduce incomes to below the minimum income requirement, pushing people into hardship, negative budgets and even destitution.[97] [98] [99] [100] [101] [102] [103] A recent survey for Trussell (2024) of people claiming UC shows that people experiencing deductions have higher levels of hunger and hardship. It found that 85% of UC claimants with deductions from their benefits had gone without essentials in the previous six months, compared to 70% of UC claimants without deductions. Further, 64% of UC claimants with social security deductions had run out of food in the previous month and did not have money to buy more, compared to 43% without deductions.[104]

There is also some evidence that benefit debt exacerbates debt problems, driving people to take on other, potentially more expensive forms of credit.[105] [106]

“Automatic deductions from benefits or wages without affordability assessments can be incredibly harmful, leading debtors to borrow from elsewhere, thus causing recurrent and persistent debt, decreased motivation and poor mental health.”

‘Responses to sector-wide survey of debt advisers’ Money Advice Trust (2020)

3.2.3 School meal debt

Local authorities have a statutory duty to offer free school meals (FSM) to some, but not all pupils. Households that are not eligible, or until recently have been ineligible, and unable to afford school meals can accumulate school meal debt.[107] Processes around school debt management vary by local authority. Primary school aged children ineligible for FSMs and who have not paid, still receive one at school, but the cost of the meal is added to their account and can accumulate.[108] Some local authorities will also pursue families for debt accrued, who are late to register for free school meals.[109]

In 2022, the children’s charity Aberlour published a series of reports on public debt and arrears, including school meal debt in Scotland.[110] These reports informed the Scottish Parliament’s Social Justice and Social Security Committee who in 2022 investigated the management and recovery of public debt and arrears, culminating in a report on low income and the debt trap.[111] The report for Aberlour (2022) showed that the families most likely to have school meal debt are those who are working and on low incomes, ‘who would have been eligible for free school meals twenty years ago’.[112]

Recommendations have been made for a fairer system of both public sector and specifically school meal debt, learning lessons from the regulation of private creditors,[113] and COSLA published good practice principles for school meal debt management in 2023.[114]

Increases over the cost of living crisis - The report for Aberlour (2022) showed high levels of school meal debt with over £1m owed and around 25,000 children whose families were in school meal debt because they cannot afford to pay for school lunches.[115] [116] Aberlour stated that by the following year (2023), this had increased by 60% to £1,763,762.[117]

“The level of school meal debt in Scotland is concerning and has been rising due to the cost of living crisis. Low income families not eligible for free school meals are struggling to feed their children, and many are accruing school meal debt as a result.”

Martin Canavan, Head of Policy & Participation, Aberlour children’s charity.

In May 2024 the Scottish Government made available a fund of £1.5 million which local authorities could apply for, to support them to clear school meal debt accrued up to 31 March 2024.[118] However, this does not help with the accrual of subsequent school meal debt.

3.3 Housing debt

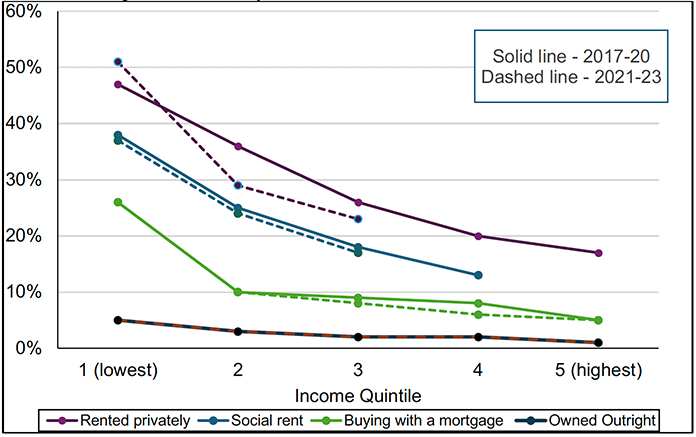

Housing costs relative to income have been highest for low income h ouseholds renting privately. Figure 3.1 shows how in Scotland, housing costs relative to household income have been higher for private rented sector (PRS) households compared to other tenures when looking at households who are on similar incomes (as measured by which income quintile in the Scottish income distribution they fall into). It also shows that the housing cost to income ratio for PRS households was higher between 2021-2023 than between 2017-20 for the lowest income quintile.

Source: Scottish Government (2024) Additional poverty analysis 2024

PRS households, particularly those who have moved and have not been protected by the emergency legislation relating to rents for sitting tenants,[119] have been subject to significant rental increases. According to Scottish Government statistics, which are based on the rents charged predominantly for new lets, the average rent for a 2-bed property (the most common privately rented property) rose by 6.2% in the year ending September 2024 to £839. While rent growth remains elevated, there are signs that it is starting to slow down – in the year ending September 2023 the average rent for a 2-bed property increased by 14.3%.

Debt amongst renters - Besides having higher housing costs relative to income ratios, those in the rented sector (more generally) are more likely to: have lower incomes than households with a mortgage; be financially vulnerable; have higher levels of poverty and child poverty; and be in fuel poverty.[120]

A range of sources show that social renters are more likely than private renters to have unmanageable debt, or need debt advice (general debt advice, rather than housing related debt advice) but that all types of households who rent their homes are more likely to be in arrears than those who own their home with a mortgage, and considerably more likely to be in debt than households who own their home outright. [121] [122] [123] [124]

Citizens Advice report that in England and Wales, high private rent and mortgage costs are increasingly driving their clients into negative budgets, with those living in the PRS having suffered disproportionately during the COVID-19 pandemic and now as a result of the cost of living crisis.[125] Official statistics show that while in Scotland 72% of social rented households are receiving some level of support for housing costs through Housing Benefit or UC, the equivalent figure for PRS households is 28%.[126]

Despite rising housing costs, data from debt advice services does not show an increase in households with rent arrears - the latest Citizens Advice Scotland data on numbers of clients with housing debt shows that there were more debt clients with local authority (LA) and registered social landlord (RSL) rent arrears than clients with private rent or mortgage arrears, and the number of clients receiving advice in relation to LA and RSL rent arrears had increased by 1% year on year between 2021/22 and 2023/24.[127]

Similarly, Scottish StepChange figures also show that the proportion of their clients with rent arrears increased by 1% point since 2022 to 22% in 2023, which was 5% points lower than the proportion of clients with rent arrears in 2019 when 27% were in rent arrears. Average rent arrears for all clients (£1,458) also plateaued between 2022-2023.[128]

This may be because households are prioritising paying their rent over paying other priority bills - The Financial Lives cost of living UK recontact survey (2024) shows that the proportion of renters (26%) falling behind on or missing paying one or more of their domestic bills or credit commitments in the previous 6 months was considerably higher than the UK average (11%). However, only 7% of renters had missed a rent payment in this period, indicating that many prioritised paying their rent over other bills. This was also the case in January 2023, when 27% of renters had missed one or more bills or credit commitments in the previous 6 months, and 9% had missed a rent payment over this time.[129]

‘Renters are struggling considerably more than average, but are prioritising rent payments’. Financial Lives cost of living (Jan 2024) recontact survey

There has been an increase in mortgage arrears and possessions over the cost of living crisis, but these increases are currently still at relatively low historic levels – Mortgage arrears and possessions have increased since low levels during the Covid-19 pandemic, due to low interest rates and protections during that period.[130]

The latest statistics (October 2024) show that following a steady increase over a three year period (2021/22 to 2023/24), the number of regulated mortgage accounts entering arrears in the UK has fallen for three consecutive quarters, although the total stock of mortgages in arrears continues to increase. In Q2 2024, the number of new regulated mortgage possessions in the UK increased by an annual 27.0%, although it remained below the quarterly average for 2019-20, prior to the pandemic. There was also a 33% annual increase in new non-regulated mortgage possessions.[131] Debt amongst mortgage holders is discussed more in this section.

Increases in homelessness applications in Scotland - the latest Scottish homelessness statistics show an increase in applications for homelessness for 2023-24. Local authorities have in part attributed this to the cost of living crisis, but it is difficult to unpick the impact of this from other factors.[132]

3.4 Consumer credit debt

Consumer credit debt takes a variety of forms, including numerous types of credit and loans. Credit card lending, personal loans, payday loans and student loans (not included here) come under this category.[133]

The studies reviewed encompass different types of consumer credit debt in their analysis and so direct comparisons between studies are difficult to make. However, the evidence suggests the proportion of people with consumer credit debt has stayed at high levels or increased over recent years.

Recent trends - Bank of England annual growth data shows a drop in consumer credit over the pandemic when households reduced or repaid their unsecured debt, but overall levels increased to pre-pandemic levels by 2022.[134] The latest statistics (30 August 2024) show that net consumer credit borrowing rose to £1.2 billion in July, from £0.9 billion in June (net borrowing through credit cards remained stable, while net borrowing through other forms of consumer credit increased).[135]

3.4.1 Credit card debt

The most recent data from the latest YouGov survey findings for the Scottish Government (September 2024) provides a measure of the proportion of people who have used borrowing of some description in the last three months that they have still to pay back.[136] This measures borrowing and not debt per se but is nonetheless helpful in understanding borrowing levels amongst the general population. The latest findings show that credit card borrowing is the most common form of borrowing (28%) amongst the Scottish adult population, followed by Buy Now Pay Later (BNPL) (14%), overdraft (13%) and borrowing from friends / family (11%). BNPL encompasses a range of different types of credit or borrowing,[137] most of which is currently unregulated (see below). The use of credit card or BNPL increased from 27% in January 2023 to 33% in January 2024. The findings also show that those ‘managing less well financially’[1] were especially likely to use a credit card (42% vs 28% overall in September 2024).[138]

A study by the Money and Mental Health Policy Institute (2023) found a rise in consumer debt between their two UK surveys in May 2022 and November 2023.[139] The research showed that consumer credit debts have the highest levels of missed payments compared with other types of debt across the time periods measured but that all key payments had seen the highest rates of arrears since November 2022.[140]

The latest StepChange Statistics Yearbook on personal debt in the UK (2024)[141] [142] shows that credit card debt has historically been the most common debt type held by StepChange clients. This is also the case among new clients in 2023, where credit card debt was held by two in three (66%) new clients. Between 2022-23, the average amount of credit card debt per client had increased by 8%, and personal loan debt by 11%.[143]

Scottish StepChange data however showed a fall in the proportion of new clients holding credit card debt, from 69% to 64% between 2022-23. However, the average balance owed on these debts increased in almost all types of consumer credit debt.[144]

3.4.2 High cost credit and loans

The FCA define high cost credit as credit products with high interest rates, such as payday loans, catalogue credit, shopping accounts, pawnbroking, home-collected loans etc.[145] BNPL encompasses a range of different types of credit or borrowing, most of which is currently not regulated by the FCA and so borrowers do not have the same protections as they would with a credit card or personal loan.[146] [This will change when the BNPL sector comes under FCA regulation, but this is not until 2026].[147]

Low income households use more expensive high cost credit and loans to pay for essentials and can pay a ‘poverty premium’ because they are not able to access mainstream credit.

Adults living on the lowest incomes, as well as unemployed adults and renters are more likely to use these forms of non-mainstream credit, often at a higher cost.[148] Fair4AllFinance (2024) found that 23% of all high-cost loans and 41% of all pawnbroker advances are held by lowest income households, while only 10% of credit cards are.[149] A review of the BNPL market by MaPS (2023) found that adults are increasingly likely to use BNPL for day-to-day essentials and the ‘struggling’ and ‘squeezed’ are more likely to face difficultly managing their BNPL payments.[150] A qualitative report by Aberlour (2023) on how public debt is experienced by low income families showed how one participant was using BNPL to buy baby milk from Amazon, due to public debt:

“… I have a Laybuy account. Laybuy is in six payments, so you pay six payments of £10. So it means I’m getting £60 of milk at once, but I’m only having to pay £10 there and then. I just pay £10 for six weeks”.

(Caroline, lone parent with four children)

Current estimates of households with high cost credit and loans - The JRF cost of living tracker survey (2024) found that around 2 million low income households hold these loans, equating to 21% of Scottish and 17% of UK low income households.[151] A review of the BNPL market by MaPS (2023) estimates that 10.1 million UK adults used BNPL in the past year. The FCA (2023) found that BNPL increased from 17% to 27% of UK adults from May 2022 to January 2023.[152]

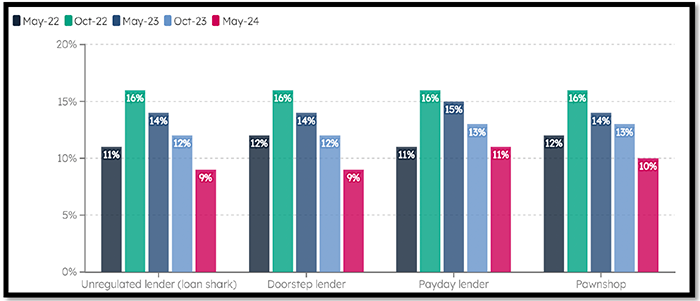

There is some evidence that the use of unregulated and high-cost credit loans amongst low income households has reduced over the last two years. The FCA’s 2023 and 2024 Financial Lives cost of living surveys show that 65% of adults with a household income of less than £15k were not coping financially or finding it difficult to cope in January 2023, which reduced to 60% in January 2024.[153] Similarly, the JRF cost of living tracker (2024) found that the proportion of UK low income households holding unsecured loans with high-cost credit providers has fallen to the lowest levels since May 2022, from around £26 billion in May 2022 to around £19 billion in May 2024.[154] Figure 3.4 shows the proportion of low income households with all types of unregulated and high cost credit loans measured was highest in October 2022 (16%) then fell to between 9-11% (according to the debt type) in May 2024.[155]

However, the report highlights that UK households in the bottom income quintile have not seen any improvement, with the proportion in arrears on some form of unregulated or high-cost credit loan remaining constant at 47% over the last 18 months.[156] This number is higher in Scotland, with 52% of households in the bottom income quintile in arrears, and 25% in the second income quintile.

3.5 Informal debt – borrowing from family and friends

A range of evidence shows that there has been an increase in borrowing from friends and family.[157] Recent research (2024) estimated that over 10 million UK adults had borrowed from friends or family in the previous year.[158]

In 2022, a report by IPPR Scotland showed that more than one in three (37%) of households in council tax arrears had to borrow from friends and family due to their debt levels compared to one in ten (9%) of all households.[159] The latest Scottish StepChange statistics (2023) show that the proportion of clients who owe money to friends and family increased between 2022-23 from 14% to 16%. The report stated: ‘Increased interest rates may be forcing people to unregulated lenders or greater reliance on friends and family’.[160]

The latest YouGov survey findings for the Scottish Government (September 2024) also show that borrowing from friends/family increased from 9-10% at the start of 2023 to 13% in March 2024. In September 2024 borrowing from friends/family stood at 11%.[161]

"We struggle. We've had to borrow off family. We're constantly watching the gas and electric meters... It's just basically because of the rising costs of food, gas and electric." (Jackie)

Treanor, M. (2023) How public debt and arrears are experienced by low-income families. Aberlour.

Despite these rises, there is also evidence that borrowing from family and friends may be becoming harder due to the impact of the cost of living crisis on the ability of networks of family and friends to lend money.[162] Lastly, it has been argued that this type of lending may not always be a harmless route, and can entail paying interest and even threats and intimidation from lenders, and may mask illegal lending activity.[163] [164] Illegal debt is also important measure, and is explored in Section 4.1

Lastly, it should be noted that demand for statutory debt solutions have not increased over the cost of living crisis. Debt solutions statistics for Scotland do not show increases over this period in line with findings above on individual debt types and in Section 6 on increasing demand for services. These statistics show that total individual insolvencies fell sharply at the start of the pandemic and have remained well below pre pandemic levels since. The number of personal insolvencies in Scotland has levelled off since Q1 2020.[165] The latest quarterly Accountant in Bankruptcy data (October 2024) show that the level of personal insolvencies in Q2 2024-25 were lower than in Q2 2023-24. In addition, 1,368 Debt Payment Programmes under the Debt Arrangement Scheme were approved in 2024-25 Q2, which is an increase of 10.8% compared with 2023-24 Q2.[166]

Contact

Email: Fran.warren@gov.scot

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback