Cost of living - effects on debt: review of emerging evidence

This report considers the evidence on the effects of the cost of living crisis on problem debt in Scotland

4. Recent changes to the debt landscape - restrictions on consumer credit

Many low income households have been increasingly unable to access regulated and mainstream consumer credit and are becoming more indebted to public bodies, with priority bills and illegal debt.

The evidence reviewed suggests that one major shift in the debt landscape over recent years can largely be attributed to significant changes in the UK credit market over the last decade. It has become harder to access consumer credit, particularly for low income households. [167] [168] [169] [170] [171] Restricted availability of affordable credit is mainly due to the introduction of reforms to the consumer credit market which the FCA took regulatory responsibility for in 2014.[172] However, over the cost of living crisis inflationary factors and higher interest rates have made consumer credit more expensive, or unaffordable, for many. A tightening risk appetite amongst lenders has exacerbated barriers to borrowing, making low cost consumer credit increasingly inaccessible for many.

‘The credit market is a complicated landscape where millions have loans used to pay for food and housing but the tightening availability of affordable credit due to stricter affordability requirements, a higher interest rate environment and regulatory changes, is an issue. This tightening will not have been the sole contributor to the levels of lending to low-income households falling, but is likely to have played a role.’ Joseph Rowntree Foundation (2024)

A tightening risk appetite amongst lenders over the cost of living crisis – the Resolution Foundation’s analysis of the Bank of England’s Credit Conditions Survey shows that lenders have tightened their risk appetite for unsecured lending every quarter since June 2022. Tighter credit scoring has particularly affected the ability of lower income households to secure credit.[173]

A significant proportion of low income households were rejected for credit in 2023. The Resolution Foundation’s UK wide cost of living survey (March 2023) found that poorer households were more likely to have been rejected for credit over the cost of living crisis, with around 13% of the poorest fifth of households rejected for credit in the previous 12 months, compared to 5% of the richest fifth.[174]

The JRF cost of living tracker (2024) shows that almost 6 in 10 UK low income households applied for credit in the previous 12 months, and of the 1.6 million households who applied, one in four (26%) were declined.[175] A further 450,000 households (4% of all low income households) did not apply because they thought they would be declined. Figures for Scotland are similar - 64% applied for credit in the last 12 months and 27% of those that applied were refused.[176] A report from CAP (2024) notes that many low income households use non-mainstream forms of credit and debt as they perceive ‘traditional credit lenders as inaccessible’.[177]

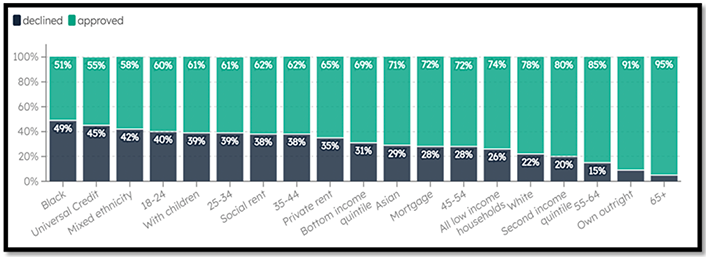

Some low income household types are much more likely to be declined than others.[178] [179] Fair4All found that younger people, those on low incomes, minority ethnic groups, renters and those living in social housing are most likely to be refused.[180] The JRF cost of living tracker (2024) reached similar findings - low income black households were almost twice as likely to be declined as all low income households, followed by households in receipt of UC, those with mixed ethnicity and young people.[181] Figure 4.1 shows the decline and approval rates of applicants for credit in the last 12 months for different low income household types.

It is important to recognise that some households will have a number of intersectional characteristics which may limit their ability to secure access to credit.

4.1 Implications of restricted credit for low income households

Many low income households have long been using credit to pay for essentials like food and housing, which can be a huge burden if households struggle to repay it. A StepChange report (2022) showed that when consumer credit is used to cover essential costs like household bills and existing credit commitments,[182] it ‘causes harm, compounds financial difficulty and lowers living standards’.[183] However, access to credit is important for financial resilience[184] and with accelerating costs over the cost of living crisis, the need for affordable credit increased, especially for households with no savings buffer.[185]

‘Balancing consumer protection with access is difficult. For many lower income households it has become harder to borrow. However, their need for occasional access to credit to smooth expenditure and manage their finances remains…

This is not to downplay the incredibly detrimental impact debt can have on people’s lives. However, for some it has removed a vital option when financial pressures have only increased’. Fair4All Finance (2024)

When this type of ‘safety net borrowing’ is not available, many of those on the lowest incomes who are denied credit can; ( i) become increasingly indebted to public bodies and fall behind with priority bills (ii) go without essentials and experience hardship and (iii) turn to illegal lenders. These are explored in turn.

4.1.1 Increasing levels of priority debt – energy and public debt

‘While using credit to pay for your bills is not a financially desirable position, it has been an important lifeline to many. But with low income families finding it more difficult to access credit, it looks like this is a lifeline that is increasingly at risk of being cut off’. Joseph Rowntree Foundation (2024) UK Poverty 2024

A recent report from the Resolution Foundation (2024) found that contrary to what might have been expected two years into the cost of living crisis, British households have ‘less consumer debt relative to their incomes than at any point since records began in 1999’. They mostly attribute this to the fall in consumer debt over the course of the pandemic when household spending reduced (amongst higher income households), but it has continued into the cost of living crisis, especially amongst lower income households. The report welcomes the findings that overall in 2023 levels of consumer debt were still below pre-pandemic levels but suggests this is partly explained by the fact that lenders have made it harder to access mainstream credit. This particularly affects low income households who, in the absence of consumer credit are accumulating priority debt instead, specifically energy and public debt.[186]

‘Higher levels of priority debt have shifted the nature of problem debt for the most financially vulnerable households.’ Resolution Foundation (2024)

The Scottish Parliament’s Social Justice and Social Security Committee in its 2022 inquiry into low income and public sector debt in 2022, heard that the types of debt low income households hold has moved away from credit cards and loans (although those debts still feature) to priority debts, for essential services, such as rent, fuel and council tax.[187]

The most recent Financial Lives survey from the FCA (2024) shows that utility bills were the most commonly missed bills over the 6 months to January 2024 (7.4% of all UK adults) and January 2023 (8.6%), followed by credit card bills (4.0% in the 6 months to January 2024 compared to 4.8% in the 6 months to January 2023), and council tax payments (3.7% compared to 4.4%).[188] The JRF cost of living tracker (2024) found that of those denied credit in the last 12 months, 85% were currently in arrears with at least one household bill. [189]

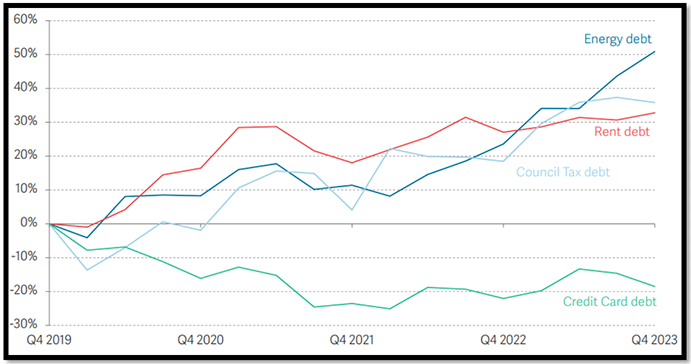

Evidence from debt advice services shows increases in priority debts amongst their clients. Citizens Advice report that amongst clients in England and Wales credit card debt, which 39% of their clients hold, has been ‘decisively overtaken’ by energy debts (50%) and council tax arrears (50%) as the most common debt issues faced by people they help.[190] The Resolution Foundation analysis of Citizens Advice data also shows that average credit card debt levels have declined among Citizens Advice clients, while average priority debt levels have significantly increased, illustrated in Figure 4.2.[191]

Source: The Resolution Foundation

4.1.2 Hardship and going without essentials

The JRF cost of living tracker (2024) shows that households denied credit in the last 12 months are disproportionately more likely to be experiencing hardship - almost all households denied credit (95%) reported going without essentials, or have used an illegal or very high cost lender.[193] This is illustrated in Figure 4.4., in Annex 2.

4.1.3 Increases in illegal lending

‘Illegal lending exists in many forms, from small-scale lenders who pester their victims into repayment to violent predators and organised crime groups. Some lenders even attempt to add a thin veil of legitimacy to their illegal lending by advertising themselves as a company, drawing up fake contracts, and independently lending to vulnerable clients while working for a separate, legitimate company’. Centre for Social Justice (2022)

Estimates of illegal lending – In 2022, the CSJ estimated that in England alone, around 1.08 million people could be borrowing from an illegal money lender or ‘loan shark’.[194] In 2024, Fair4All Finance research estimated that in the past three years 3.3 million people used, or believe someone in their household used, illegal moneylenders.[195]

There is emerging evidence that those denied access to regulated consumer credit are turning to illegal lenders.[196] [197] [198] [199] A recent report by Fair4All Finance (2024) investigates the changing shape of the consumer credit market and how the illegal lending market is developing in the UK, both in the community and online.[200] [201] The report shows a growth in ‘unregulated, potentially dangerous or exploitative lenders’, which they suggest may in part be an unintended consequence of enhanced regulation in the UK credit market.[202] It found that 16% of those declined for regulated credit had either used a loan shark, or know someone in their household who had, compared to 5% of people who had successfully applied for mainstream credit.[203]

“Because I knew the bank wouldn’t give me one…Because I am what you class as a poor person.” (Client, Preston) Fair4All Finance (2023)

An accompanying qualitative report by Fair4All Finance (2023) on experiences of illegal money lending also found that victims have significantly higher credit application refusals than the UK average.[204] This echoes the findings from the JRF cost of living tracker (2024), which found over a third of low income households refused regulated credit options hold loans with loan sharks, doorstep lenders, payday lenders, and pawnshops, almost 4 times more likely for each loan type than those who successfully applied for credit (see Annex 2).[205] The CSJ report (2022) also found that victims of illegal money lenders borrow from loan sharks as a last resort after trying other sources.[206]

“This report… indicates the risks of a rise in criminal activity if access to credit becomes the preserve of wealthier households. There are dangers if the credit market size and shape does not fit all”. Fair4All Finance (2024)

The CSJ report (2022) highlights a recent shift in illegal lending practices, with more operating online and using social media ‘to entice and exploit new victims’ through often relentless forms of online manipulation.[207] It shows how most victims of illegal money lending face multiple disadvantages and vulnerabilities, but victims also include more affluent households and homeowners.[208] There is some evidence of threats and intimidation from illegal lenders, to repay their loans.[209]

“Stuff was going to happen to me, but not just me, I get threats came for hurting my family, do you know what I mean? It was oh your mum is getting this, your brother is getting this.” (Client, Glasgow) Fair4All Finance (2023)

4.2 Impacts of growing levels of public sector and priority debt

There is a two-way relationship between debt and health, with poor mental and physical health both a cause and a consequence of problem debt.[210] [211] [212] Evidence suggests that people with mental health issues are ‘three or more times more likely to have problem debt’.[213] Studies on the impacts of different debt types all demonstrate the harmful health effects of problem debt, with evidence of multiple harms associated with consumer credit debt.[214] [215] [216] However, recent evidence shows a particularly strong association between public and priority debt and poor mental health.[217] [218] [219]

In 2022, a report by IPPR Scotland for the Robertson Trust (2022) emphasised how debt and arrears to public bodies can often have some of the ‘greatest negative impacts.’ It found that adults owing money to public bodies were going without essentials, and more than half of households (51%) behind on council tax were having to cut back on food to save money.[220]

Harms associated with energy debt - Ofgem highlight the harms associated with indebted households self-rationing their energy, with PPM consumers more likely to self-disconnect[221] in order to redirect funds to repay debts rather than heat their homes. Restricting energy consumption, especially over winter periods can elevate the risk of health harms as a result of living in a cold, damp home,[222] with some groups like children and elderly people being particularly negatively affected.[223]

Consumer Scotland’s Energy Affordability Tracker study (2024) showed that being in energy debt is associated with a substantially elevated rate of impact on physical and mental health, even after controlling for income, age and health. One third (31%) of those in energy debt reported that keeping up with energy bills impacts their physical health ‘a lot’, and 45% report that it negatively affects their mental health ‘a lot’ (compared to 4% and 7% of survey respondents not in energy debt).[224]

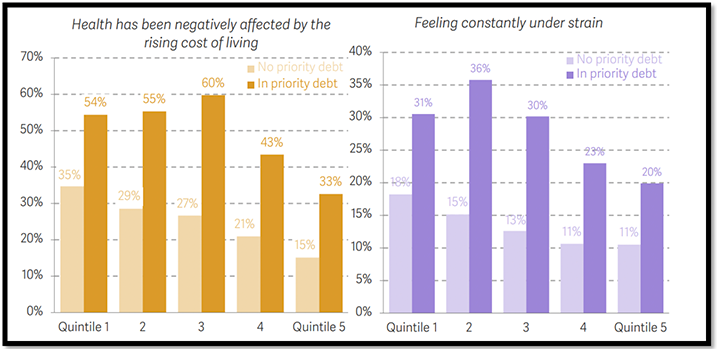

The Resolution Foundation analysis (2024) of the significant effects of debt on adults’ mental health and wellbeing looked at the effects of being in both consumer and priority debt. Regardless of income level, people in the UK with consumer debt report markedly worse health outcomes than adults without consumer debt.[225] However, the link between debt and wellbeing was most pronounced when looking at priority debts. Negative health outcomes are much more common among people with priority debt than those with consumer debt and even at higher income levels, individuals with priority debt are around twice as likely to report experiencing negative health outcomes.[226]

Source: The Resolution Foundation

This is largely a result of the weaker protections for the person in debt, the punitive debt recovery practices and high stakes consequences of priority and public sector debts which are not regulated to the same standards as consumer credit debt.

Public sector debt regulations and recovery practices have not improved in line with consumer credit regulations.[227] [228] [229] [230] [231] Much of the evidence reviewed found that these practices - and the consequences of not paying these debts - are particularly punitive. Repayments and deductions for public debt and priority bill arrears are recouped considerably quicker than for private debt, which can result in harsh enforcement, such as summary warrants or eviction.[232] [233] [234] This can exacerbate debt problems, further pressurise household finances and harm health.[235] [236] [237] [238]

‘Living on a low income and having debt, especially public debt, with its uncompromising collection practices, is strongly linked to mental health problems, due to people’s fears of losing their homes and incomes altogether’. Aberlour (2023)

Scottish evidence (2022) highlights how the pursuit of debt, particularly the ways in which creditors engage with people in public debt and arrears and aggressive collection methods can exacerbate financial and mental stress and distress.[239] [240] Citizens Advice research (2023) found that more than a third of adults who have been contacted by bailiffs have experienced threatening or unfair behaviour leaving them feeling intimidated and afraid to open the door, and that 3 in 4 people who have experienced bailiff action said that it took a toll on their mental health.[241]

‘At the sharp end of public sector debt collection, substantial and unpredictable direct deductions from wages or benefits, and the threat of more severe consequences, such as involuntary bankruptcy and imprisonment, can profoundly undermine our mental wellbeing.’ Money and Mental Health Policy Institute (2024)

A number of sources highlight council tax penalties as especially severe.[242] [243] [244] [245] The Poverty and Inequality Commission (PIC) cost of living briefing (2022) heard from advice services that council tax is a ‘particular issue’ and the punitive approach to debt collection is damaging, and in need of reform in order to start ‘treating people with dignity and respect when pursuing arrears’.[246]

A recent report by the Money and Mental Health Policy Institute (2024) highlights how people with mental health problems are both more likely to be in debt and are especially vulnerable to the rapid debt collection processes often used to recoup public sector debt. It found that people with mental health problems are more than twice as likely to be behind on council tax payments as those without (driven by lower than average incomes, higher relative costs and difficulties managing money and accessing help) and people with experience of a severe mental illness are four times as likely to be in council tax debt (16% compared to 4%).[247]

In 2019, the Improvement Service, local authorities and advice providers published a best practice collaborative guide to council tax collection.[248] This report, and reports by others, [249] [250] [251] provide guidance on good practice debt policy and recovery, and supporting vulnerable people in debt and arrears.[252] However, there are calls to do more to support people before they seek advice on council tax debt, including in relation to the 20 year prescription period for council tax in Scotland.[253] [254] [255] There is also some recent evidence that harmful recovery practices may be increasing.[256]

Much of the evidence reviewed suggests this is particularly concerning and acute at a time when many households, including those who have never been in debt before, may begin falling behind on payments and into financial insecurity.[257]

‘Given the shift from consumer debt to priority debt over the past few years, the particularly high levels of negative health outcomes for those in priority debt should give us cause for concern.’ Resolution Foundation (2024)

Contact

Email: Fran.warren@gov.scot

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback