Litter and flytipping offences - enforcement review: final report

We commissioned this research report in 2022 and it was completed by Anthesis in autumn 2023. This project aimed to review the current enforcement model in Scotland and offer recommendations to strengthen that enforcement.

The key barriers to enforcement

There is agreement among many stakeholders involved that there is no one solution to tackle the issue of litter and flytipping enforcement, and that a joined-up and collaborative approach is needed. There are currently a range of barriers to the use of existing enforcement powers which were identified through the evidence and literature review as well as stakeholder engagement.

Key barriers

Identifying the offender

It is recognised that a lack of evidence around who dumps waste or who the waste belongs to prevents those responsible from facing the appropriate consequences. This makes it difficult for enforcement bodies to determine their enforcement options, limiting the success rate of enforcement. This was flagged as a key barrier by stakeholders interviewed as part of the project.

In the case of flytipping, an inability to identify the offender limits the number of flytipping incidences that can be taken forward by the Procurator Fiscal and can proceed to court. Flytipping is also often associated with dumping waste from vehicles. The person who owns the vehicle can be prosecuted, meaning it is possible for a prosecution to occur when only the vehicle, not the driver, is identifiable.

Identifying the offender (and witnessing the crime) is also a key barrier for the application of littering enforcement. This challenge has been cited as a reason for the low level of FPNs issued for littering offences. As such, offences are not recorded or pursued because the individual cannot be officially identified. This creates a gap in current enforcement, weakening the deterrent power of the FPN.

Scotland’s Circular Economy Bill[146], introduced in 2023 and which underwent public consultation in 2022 includes a new enabling power that will allow a civil penalty to be issued to the registered keeper of the vehicle when an enforcement officer is satisfied on the balance of probabilities that a littering offence has been committed from that vehicle, in the hope of increasing the deterrent effect and options available to enforcement officers in tackling roadside litter. In addition, a large amount of littering happens around schools, bringing its own challenges for enforcement and the use of enforcement powers when identifying offenders.

Enforcement bodies such as local authorities and Loch Lomond and the Trossachs National Park Authority are sometimes given fake names and addresses as individuals perceive that they are not being dealt with by the Police so can get away with it. Loch Lomond and the Trossachs National Park Authority fund a police officer to cover the local area and assist with patrols and act as a liaison officer. This additional resource is particularly helpful in getting legitimate information from offenders.

The public consultation for a Circular Economy Bill[147] for Scotland sought views on whether enforcement authorities such as SEPA and local authorities should be given powers to seize vehicles linked to waste crime, in an aim to minimise waste crime and align Scotland with the powers available in the rest of the UK. Currently vehicle seizure powers in Scotland are under Section 6 of the Control of Pollution (Amendment) Act 1989 (COPA 89) and require an enforcement authority to obtain a warrant from the sheriff[148]. Such powers could be used in addition to financial penalties, helping to make a more robust enforcement model.

Collecting robust and appropriate evidence

In addition to identifying the offender there are challenges around collecting the evidence required. For an enforcement authority to issue an FPN for littering or flytipping, there must be a reason to believe that the person has committed the offence. For SEPA to issue a FMP or VMP there needs to be evidence that the responsible person has committed the offence to which the penalty is related. Collecting robust and appropriate evidence will impact the number of cases passed to and taken forward by the Procurator Fiscal as reports can only be taken forward if there is sufficient evidence. This means, for flytipping offences, that there must be corroborated evidence in relation to both the offence and the offence. These means that there must be evidence from two sources, which can be provided by witnesses, CCTV, admissions or surrounding facts and circumstances. For littering, corroboration is not required and the evidence of a single witness is sufficient. This challenge may mean that enforcement bodies are not using the available powers as much as they could be due to the likely challenge of witnessing the offence or having the appropriate level of evidence to issue a penalty in the first place and then pass it to the Fiscal if further action is required. Where there is insufficient evidence included in a report passed on for prosecution, COPFS will, where appropriate, work with the reporting body to identify other areas for enquiry and instruct the gathering of any additional evidence available.

COPFS also require details of any interviews with the accused that took place and whether these were under caution. If an accused is not cautioned, then any answers are likely not admissible in Court. Any conversations with an accused, where prosecutors seek to rely on admissions made, will be governed by a general rule of fairness. The police hold powers to interview suspects under caution. However, the admissibility of remarks/admissions/explanations by a suspect by other enforcement officials can be admitted in certain circumstances if obtained fairly. There is nothing which prevents a caution being given by Specialist Reporting Agencies in order to increase the likelihood that the test of fairness will be met.

Fixed Penalty Notices (FPNs)

Recovering Fixed Penalty Notices (FPNs) can often be challenging. One of the main barriers to effective enforcement and the use of current powers is the lack of follow up between a FPN being issued and being paid. If FPNs are issued but not paid, the case can be passed to the Procurator Fiscal, however, the ability of the Procurator Fiscal to take reports forward is dependent on the sufficiency of evidence.

When FPNs are not paid (and cases are not prosecuted, in many cases likely due to a lack of evidence) it unavoidably gives the message that individuals can get away with the crime without any punishment. The threat of consequence looks empty and undermines the effectiveness of the model. This may also make enforcement officers less willing to use existing powers as the ability of the offender to get away without paying the FPN or being prosecuted can make the act of issuing a penalty seem pointless. For enforcement to work, actions taken need to be followed through so both potential offenders and enforcement officers know that the threat of a FPN actually means something.

Taking Inverclyde Council as an example authority that regularly publishes flytipping and littering enforcement data on its website, the issue of FPNs being paid can clearly be seen (Table 7). Between 2018/19 and 2022/23 on average, only 36% of FPNs issued for flytipping were paid, and 34% of FPNs issued for littering were paid. Local authorities also have powers to issue FPNs for other offences such as dog fouling. The average percentage of FPNs paid for dog fouling is 51% which is somewhat higher than the average paid for littering and flytipping.

Year |

Flytipping |

Litter |

Dog Fouling |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Financial Year |

FPNs issued* |

FPNs paid |

% |

FPNs issued* |

FPNs paid |

% |

FPNs issued* |

FPNs paid |

% |

2018/19 |

4 |

2 |

50 |

15 |

6 |

40 |

34 |

17 |

50 |

2019/20 |

17 |

7 |

41 |

15 |

2 |

13 |

18 |

8 |

44 |

2020/21 |

27 |

9 |

33 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

7 |

5 |

71 |

2021/22 |

8 |

2 |

25 |

3 |

2 |

67 |

13 |

7 |

54 |

2022/23* |

17 |

5 |

29 |

2 |

1 |

50 |

8 |

3 |

38 |

Average |

36 |

34 |

51 |

||||||

FPNs issued are minus of any cancellations |

|||||||||

Published local authority data on the number of FPNs issued and paid is rare. In addition to Inverclyde Council, Moray Council has released data under FOI request[149]. The data shows that between 2010 and 2021 on average 54% of FPNs issued for littering were paid (Table 8 FPNs issued for littering and paid in Moray Council between 2010 and 2021 (Moray Council 2023)), though it should be noted that between 2010 and when the data was released (mid-2021) only 34 FPNs were actually issued for litter offences. A separate FOI request[150] sought information on the number of FPNs issued for dog fouling and the number of FPNs paid. The average percentage of FPNs paid for dog fouling between 2016 and 2021 was 48%[151]. While more FPNs are paid for dog fouling than littering in Inverclyde, this is the opposite in Moray. Regardless, the percentage of FPNs paid is around half or less for all offences.

Year |

Litter FPNs Issued |

Litter FPNs Paid |

% |

|---|---|---|---|

2010 |

5 |

4 |

80 |

2011 |

1 |

1 |

100 |

2012 |

2 |

2 |

100 |

2013 |

11 |

4 paid, 7 went to invoice |

- |

2014 |

5 |

4 |

80 |

2015 |

5 |

5 |

100 |

2016 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2017 |

3 |

1 |

33.3 |

2018 |

2 |

2 |

100 |

2019 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2020 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2021 to date |

0 |

0 |

0 |

Average |

53.93 |

Without more data it is challenging to see if the low number of FPNs paid is consistent across Scotland, however, stakeholder engagement has indicated that the number of FPNs paid tends to be low. If more local authorities published data on FPNs issued and paid it may be possible to see patterns and trends across all the different types of offences that can be subject to an FPN. This would allow more of an assessment of whether litter and flytipping FPNs tend to go unpaid and whether this algins with other crimes or not.

While chasing unpaid FPNs is clearly linked to resources, guidance from the Welsh Government to enforcement bodies in Wales, states that “it is not acceptable for an authority to decide after a fixed penalty notice has been issued that it does not have the resources to prosecute if the notice is unpaid”[152]. Guidance in England is similar, with Defra stating that the enforcing authority should be prepared to prosecute offenders for the original offence if an alleged offender does not pay a FPN, as failure to follow up on unpaid FPNs undermines their effectiveness as an enforcement tool[153].

Enforcement bodies’ priorities

Those with enforcement powers (Police Scotland, SEPA (flytipping only), local authorities and Loch Lomond and the Trossachs National Park Authority) have a range of responsibilities and litter and flytipping is only one of them and, understandably, it is not the top priority, however, this is likely to differ amongst the different bodies. Engagement has also indicated that litter and flytipping and its enforcement is also prioritised differently even within the one organisation and between departments. SEPA and Police Scotland often face more significant instances of environmental crime and crime respectively so prioritisation of flytipping is likely to be lower.

In addition, enforcement agencies interviewed as part of the project indicated that tight budgets mean that litter and flytipping enforcement slips down agendas and is not seen as a priority and is therefore not adequately resourced.

This leads to enforcement powers and prevention measures (education and awareness) being used inconsistently and is a key barrier to the use of existing powers and measures. If litter and flytipping are not viewed as serious environmental and social issues (and crimes) that represent a leak from the circular economy, then this can lead to significant under resourcing in terms of both personnel and budget.

Resources

Enforcement requires resources and skilled staff, legal resources, court time and administration[154]. Existing enforcement bodies in Scotland are either local government, public sector bodies or executive non-departmental public bodies and as such, their funds are at least in part (if not fully), publicly funded, meaning that budgets and resource availability is closely linked with wider pressures on public funding and the allocation of budgets.

While enforcement can raise funds, an effective enforcement model should not be used purely to raise funds but to act as a deterrent. Under the current model, where FPNs are not recovered, and prosecutions and convictions are low, there could be the perception amongst enforcement bodies that the current system is not worth properly resourcing as the success rate is so low and the system not working effectively. A recent poll conducted by the Local Authority Recycling Advisory Committee (LARAC) found that “more than 90% of council recycling officers think their employer has insufficient resources to effectively tackle waste crime”[155]. The survey found that data, costs and human resources were the three biggest obstacles to effectively building an understanding of the full extend of waste crime[156]. This is turn can hinder any preventative measures.

Anecdotal feedback from some local authorities suggests that if they have money to spend on flytipping it will be spent on clean-up not on investigation or enforcement. While more successful enforcement outcomes may encourage more local authorities to spend in this area, the issue complex, with multiple factors at play. Whilst penalties paid to local authorities in relation to FPNs are accrued by the local authority to which they are paid, SEPA has to remit all penalties paid by it from FMPs and VMPs to the Scottish Ministers, with the monies then remitted to the Scottish Consolidated Fund. The process of passing penalties received by SEPA to the Scottish Ministers and thereafter, the Scottish Consolidated Fund was put in place to ensure there could be no accusation that there is an incentive for SEPA to issue penalties to generate income.

It has previously been highlighted by some that the power to issue FPNs should be extended to other bodies such as Traffic Scotland, Forestry and Land Scotland and Cairngorms National Park[157]. Such landowners/managers have extensive areas that are often subject to both litter and flytipping, yet enforcement powers only extend to the local authority where the area is situated (with the exception of Loch Lomond and the Trossachs National Park Authority). In some cases, local authorities do not have available resources to dedicate to such large areas that are popular with visitors[158]. Giving other bodies enforcement powers could increase the number of enforcement officers and spread responsibility out across additional bodies. This needs to be considered alongside other requirements such as training and how to promote a consistent and coherent model.

In England and Wales, private contracts for enforcement staff, who have powers to issue FPNs for littering, are used. Engagement with Welsh stakeholders suggested that the use of private contracts can be particularly useful for littering. While such contracts can help with personnel resources there is sometimes still a budgetary consideration, and they can often attract media attention and controversy. One of the limitations of private contractors is that there are potentially fewer opportunities for holistic prevention strategies[159] as they tend not to be trained in engagement management and can be driven by profits rather than preventing the issue at source.

Due to resource constraints, some enforcement stakeholders interviewed for the project outlined that a judgement call often needs to be taken on whether the crime is worthy of investigation. Other key factors that influence whether a crime is investigated is whether the dumped waste poses an environmental or human health hazard. While not directly linked to the availability of resources the local authority survey carried out for this project also highlighted safety concerns for on the ground enforcement officers (from abusive members of the public) and the impact this has on staff working on enforcement.

Clarity of messaging

Consistent and clear messaging has a vital role to play in changing social norms and ensuring any enforcement model works well. A lack of clarity on the different enforcement measures available and when each should be used is also a key barrier to the use of existing powers. It can also be challenging for enforcement bodies to provide members of the public or private landowners advice due to the lack of continuity and joint messaging across Scotland.

While various bodies across Scotland communicate that littering and flytipping is an offence, there is still a lack of awareness of the consequences of committing these crimes. The consultation for the new National Litter and Flytipping Strategy outlined the need for common language and messaging that is used consistently across Scotland to ensure there is no confusion around what littering and flytipping are and what should be done about them.

While a consistent approach is needed there also needs to be consideration that one size will not always fit all and that local factors should be taken into account. This is also true of national campaigns and was seen during Zero Waste Scotland’s “Scotland is Stunning” campaign (delivered in partnership with Scottish Government and KSB).

The national campaign looked to inspire positive reinforcement, repeating the term ‘our’ to cement the sense of collective responsibility and pride for public spaces, with imagery being adapted for local areas. The campaign focused on the impact rather than the problem to instil a sense of positive connection to the environment and inspire the audience to make the right choices. There are learnings that can be taken from such national campaigns with clear messaging, that also allow a degree of local interaction when it comes to thinking about consistent but meaningful behaviour change messaging around enforcement. Appendix 7 – The impact and effectiveness of campaigns on behaviour change provides a more detailed overview of the impact and effectiveness of national campaigns on behaviour change. Demonstrating that campaigns work and having the funds to deliver effective campaigns is also a key challenge, in addition to ensuring that impacts are delivered in the longer term.

In addition, Scotland attracts a large number of tourists, with popular destinations and tourism sites often facing large quantities of litter. It is challenging to ensure that messaging is relevant and applicable to those who may only be in Scotland for a few days, however, given the scale of tourism and the challenges many tourist hot spots have faced with littering (and also flipping in the case of campers in national parks), it is important that messaging is accessible, and makes it clear that Scotland does not tolerate litter and flytipping.

Education (and a clear and consistent message) for on the ground enforcement officers is also vital. Stakeholder engagement highlighted that there may be a lack of understanding amongst some Enforcement Officers as to the powers that are actually available to them. There needs to be clearer information on the crimes, what penalties are available and additional guidance.

Prosecutions

Some stakeholders interviewed as part of the project felt that one of the key challenges with litter and flytipping enforcement is that court proceedings must compete with offences that are often more serious or perceived to be more serious. This only reflects the views of some stakeholders and also does not represent the views of COPFS, SCTS or members of the judiciary. While some stakeholders felt that litter and flytipping cases may not be worth pursuing by the Procurator Fiscal, engagement with COPFS highlighted that where there is sufficient evidence to prosecute, they will consider all reports in line with the prosecution code.

One stakeholder (not COPFS, SCTS or members of the judiciary) highlighted that it is likely not a sensible use of court resources to pursue litter and smaller scale flytipping offences and spending time, money and resources on individual offenders will not solve the wider problem. This would not apply to larger-scale incidents or those involving organised crime groups, or potentially repeat offenders. Stakeholders (not COPFS, SCTS, or members of the judiciary) highlighted that it can be frustrating when a case is put together and passed on for further action, but there is then no further action taken. Some also felt that sheriffs need to know more about the cost of clearing up flytipping when passing down fines to ensure they are representative. For cases passed on by SEPA, this would be included in the Standard Prosecution Report.

Engagement with local authorities suggested that local authorities sometimes do not send cases to COPFS as they believe they will not be followed through. 69% of local authorities surveyed as part of this project feel that cases passed to COPFS are not successful, while only 31% feel that the number of prosecutions has an influence on litter and flytipping occurrences and acts as a deterrent.

When passing on cases for prosecution, enforcement officers compile a standard prosecution report. There may be some difference in the reports received by COPFS from the police and local authority officers due to the police potentially having more experience and therefore knowledge of what COPFS require for sufficiency. There can also sometimes be communication issues between COPFS and local authorities, due to communication not being managed directly/centrally as is the case with the police.

Consistency of approach

Scotland has 32 local authorities, that all have a statutory duty to keep their land clear of litter and refuse (in addition to a significant number of private landowners). While this statutory duty is underpinned by legislation set by Scottish Government there are likely to be variations in how litter and flytipping instances and enforcement activity across Scotland is approached.

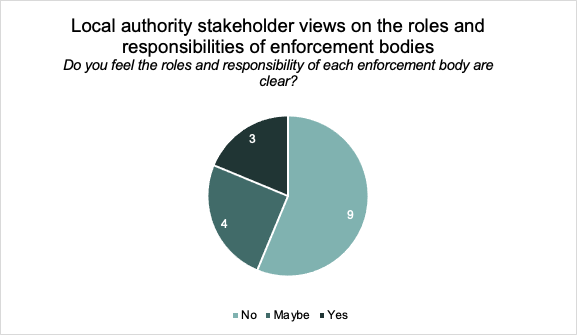

Under the current model, there appears to be a lack of clarity around the roles and responsibilities of different enforcement bodies, with 56% of local authority respondents surveyed as part of the project feeling that the roles and responsibilities of each enforcement body are not clear (Figure 12 Local authority stakeholder views on the roles and responsibilities of litter and flytipping enforcement bodies in Scotland (views gathered in local authority survey issued as part of this report). This seems to be a particular issue when it comes to private land and the boundary between landowners (e.g., local authority boundaries, private-public land boundaries). This issue mainly relates to whose responsibility it is to clear up flytipping but also extends to who deals with enforcement action.

The issue around consistency of approach and unclear messaging was highlighted by some stakeholders in relation to the wider waste and recycling landscape in Scotland (e.g., household recycling variations across local authorities). It is, however, noted that the voluntary Charter for Household Recycling and associated Code of Practice are looking to address this. SPARC (see case study) is an example where a collaborative approach has proved to be a success in bringing together key stakeholders to tackle the issue of flytipping in rural areas.

It is recognised amongst stakeholders and in existing literature and evidence that the current enforcement model is inconsistent when it comes to issuing FPNs and other measures, leading to a lack of buy-in from stakeholders and acting as a key barrier to the use of enforcement measures. The perception of FPNs and their effectiveness is often “different from one local authority to another from one legal department to another, between Procurators Fiscals and perhaps even between Sheriffs”[160]. There was also feedback from stakeholders that enforcement action could be taken in a local authority area by an enforcement body such as Police Scotland or SEPA, but this is not communicated with, or passed to, the local authority so they are unaware of action taken within their local authority. Communication between enforcement bodies was raised by several stakeholders and can result in a lack of a joined-up and collaborative approach. In addition, some operational staff are not always aware of what SEPA can offer.

Within Loch Lomond and the Trossachs, there are five enforcement bodies (not including the Police and SEPA); the National Park Authority and four local authorities. All have enforcement powers but exercise these duties differently. This is likely to cause confusion and act as a barrier to enforcement as one body might think another is dealing with an incident. When it is reported in the press and media that strong action is being taken in one local authority area, but not in a neighbouring authority it can lead to the perception that the approach is inconsistent and that enforcement is not effective.

While the approach to litter and flytipping enforcement was generally found to be inconsistent, some stakeholders did highlight that intelligence sharing between SEPA and Police Scotland is effective when it comes to organised crime. The local authority survey found that in some cases, local authorities find there is a lack of support from other enforcement bodies (the police and SEPA). Scotland currently has a Flytipping Forum[161], which has the purpose of bringing together key stakeholders to discuss how to implement the new strategy and share best practice and insights relating to tackling flytipping. There is an opportunity for the Forum to focus on actively be promoting intelligence sharing between enforcement bodies, pushing good practice, ensuring collaboration and consistency in approach.

Case Study: Scottish Partnership Against Rural Crime (SPARC)[162]

SPARC is a multi-organisation agency collectively working to prevent, reduce and tackle rural crime, especially regarding the threat posed by Serious Organised Crime Groups (SOCGs) in Scotland. SPARC seeks to provide a coordinated approach to crime prevention, treating all cases seriously and ensuring they are dealt with in a timely manner, which has led to a high level of sustained, and ongoing community trust in the organisation. As a result, rural communities are engaging with their local Partnership Against Rural Crime group to report incidences of rural crime, they are also signing up to Rural Watch Scotland Alerts and phoning in to report a rural crime.

One of SPARC’s top priorities when it comes to rural crime is tackling incidences of flytipping. SPARC believes in consistency of approach and is working with Zero Waste Scotland to develop an action plan against flytipping with short, medium, and long-term goals.

Short-term goals include understanding the behaviours that lead to flytipping so targeted approaches can be developed.

In the medium-term, SPARC seeks to develop and adopt a shared approach between stakeholders to flytipping prevention and behaviour change across Scotland. They recognise that this will require a more effective enforcement model, a national anti-flytipping campaign delivered through a successful, single point for information.

In the long-term, SPARC aims to improve understanding of the sources, levels, and composition of flytipping as well as the geospatial and temporal patterns associated with flytipping incidences. This will require data sharing between organisations to develop a live picture of flytipping across public and private land in Scotland.

A key theme amongst stakeholder interviews was the need for a collaborative approach, with more advice and guidance and a clearer understanding of different bodies’ roles and responsibilities. Some stakeholders expressed a view that the cross (local authority) boundary movement of waste for flytipping causes a particular challenge as the perpetrator may not dump the waste in the area in which it originated. This, coupled with the fact it can often be left on private land, causes further challenges with reporting and enforcement and identifying the culprit. Barriers in communication between all the enforcement bodies was also raised by stakeholders as a key barrier and can in some cases prevent flytipping incidents and flytipping enforcement being consistently tackled. Collaborations like SPARC help to create a joined-up approach between the multiple stakeholders involved in flytipping and enforcement.

Some stakeholders (not those directly involved in enforcement) highlighted that the enforcement model is somewhat siloed, leading to a disjoined approach and that there needs to be more open communication to track cases and those that are passed on for prosecution.

Data

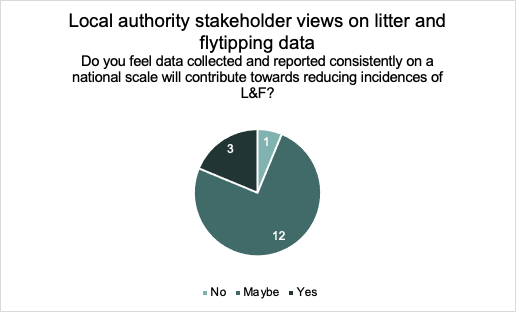

Currently it is challenging to understand the national picture for litter and flytipping occurrences. Data is collected via multiple channels, causing confusion for those reporting instances and meaning information on cases is spread over different platforms/systems. In addition, it is not a statutory requirement for duty bodies to report cases, resulting in flytipping instances not being reported. This makes it challenging to fully understand the issue with flytipping in Scotland and the scale of the problem. Local authority views on consistent data reporting were gathered as part of this project, with the majority feeling that data collected and reported consistently could contribute to reducing incidents (Figure 13 Local authorities stakeholder views on the role of litter and flytipping data (views gathered in local authority survey issued as part of this report). While there is a lack of recording and also consistency in any data that is recorded, data is also not uniformly shared across different regions and agencies again leading to a lack of consistency and joined up approach.

Individual responsibilities

In the case of businesses, flytipping is related to the duty of care legislation which impose requirements in relation to r waste management. Businesses must adhere to these requirements, which aim to prevent the illegal deposit of waste they produce and must also have an accurate account of their waste when it is transferred to a waste disposal company or third party. Businesses must directly pay for the removal of their waste, unlike householders who pay for this service (legitimate waste disposal) as part of their council tax, with limited use of private commercial waste disposal for things such as house renovations. This means that some businesses may try to avoid paying fees for commercial waste collection by illegally dumping their waste.

Over 70% of flytipped waste in Wales contains unwanted household items and rubbish, most often, this is a result of householders unknowingly putting their excess household waste into the hands of a flytipper[163]. Residents need to be aware of the risks associated with using private contractors and the requirement for waste collectors to have a waste carrier’s licence. A lack of individual awareness of duty of care responsibilities could generate more business for unauthorised waste services which undermines waste carrier licensing.

There is a lack of awareness around the need to use a legitimate, registered, waste carrier for household waste. This will likely act as a barrier to effective enforcement and the number of FPNs paid as individuals may perceive (in the case of flytipping) that they have not committed the crime of flytipping This is also seen where individuals place waste next to a bin in the belief that they have left it out for collection, when in fact this is classified as flytipping. It should be noted, however, that this is not clear cut as while some local authorities class this as flytipping, others classify it as ‘side waste’. Individual responsibilities are closely linked to the clarity of messaging and ensuring that clear communications are provided to householders around what constitutes litter, flytipping and duty of care, and the enforcement actions that can be taken against them for such offences. This is closely linked to behaviour change which is discussed in the following section.

In addition to the requirement to use a registered waste carrier, stakeholder engagement highlighted that some individuals feel that it is their council’s responsibility to clear up waste, whether put in the provided bins or dumped illegally. Local authorities have a statutory duty to clear up waste in a timely manner, and while quick removal can often prevent additional items being left and one solitary household item turning into a pile of dumped items, it is a complex situation as this can also send the signal to residents that local authorities are on hand to clear up the waste they dump illegally, and they get used to this. Strong enforcement could help to mitigate this risk, but is strongly linked to the barriers outlined above, specifically the challenges around identifying the offender, gathering evidence and enforcement body resources.

Additional barriers for consideration

While enforcement has a clear role to play, an effective enforcement model needs to be underpinned by initiatives that promote good behaviour and act as a deterrent in preventing litter and flytipping at source through a change in public behaviour via increased awareness and individual accountability.

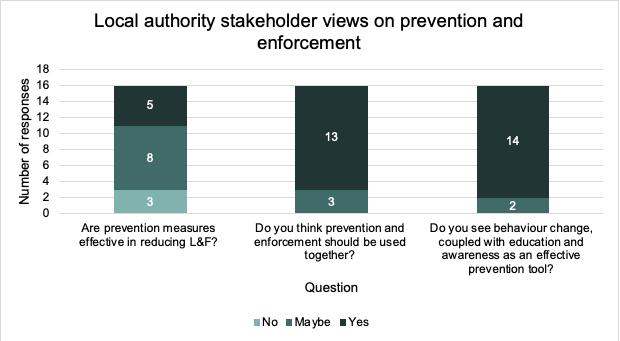

Local authority views on prevention and awareness were sought via a self-completion survey (Figure 14 Local authority stakeholder views on litter and flytipping prevention and enforcement (views gathered in local authority survey issued as part of this report), with 81% answering “yes” or “maybe” when asked if prevention measures are effective in reducing litter and flytipping. 81% felt that prevention and enforcement should be used together (zero respondents answered “no” to this question), whilst 88% see behaviour change coupled with education and awareness as an effective prevention tool, again zero respondents answered “no” to this question (Figure 14 Local authority stakeholder views on litter and flytipping prevention and enforcement (views gathered in local authority survey issued as part of this report).

The role of behaviour change has long been recognised, with the 2014 National Litter Strategy[164] stating that tailored local messaging could help to influence behaviour by motivating people to do the right thing. Methods suggested included street art, signs and bin designs, with messaging including the effects of litter and flytipping on people and wildlife, or by focusing on a certain type of litter or litter in a particular environment.

Research into the prevalence of COVID-19 related litter[165] found that littering amongst nations varied due to local legislation and guidance which ultimately impacted the quantity of single use items being used. Observed variations were seen to be complex, with the quantity, composition and distribution dependent on a number of factors. The factors for COVID-19 related litter align closely with factors related to littering and flytipping more widely including infrastructure (convenient and suitably placed litter bins), service provision (street cleansing, litter bin collections, communication materials and enforcement of penalties) and desirable public behaviour (that is, choosing to not litter)[166].

Littering particularly is a difficult behaviour to change, with conventional methods focusing on public education campaigns to convince people that littering is morally wrong[167]. Messaging that leverages behavioural science is also often not effective if good disposal options are not conveniently available[168]. Changing social norms can often prove effective in reducing littering, with communication nudges playing a key role. Both littering and small-scale flytipping often come down to an individual’s risk analysis of whether committing a minor crime is worth it.

Who litters and flytips and why?

Littering and flytipping, as outlined above, can be caused by a variety of factors that are not always easy to identify. However, there are some common factors that are often associated with these behaviours. These include a lack of awareness and information about the consequences, costs, and social health. Additionally, a perceived lack of enforcement, the inconvenience when the infrastructure is unreachable or difficult to use (no bins, not enough recycling points or collections services for bulky waste) and attitudes and beliefs around responsibility can all contribute to littering and flytipping.

The analysis of responses for the public consultation on the new national litter and flytipping strategy found that responses (78% for litter; 65% for flytipping) supported conducting research to understand the full range of influences on behaviour. In the case of littering the analysis states it is believed that “such research will help assess existing impacts and management plans, and to inform future action and prevention measures”[169]. For flytipping, respondents who supported the action say it is “important to understand the behaviour behind flytipping as this will inform appropriate actions and sanctions that can be implemented”[170]. Motivations for flytipping are generally found to be cost related to avoid paying for waste disposal services as well as such services being located too far away. In some cases, laziness plays a role, along with the perceived lack of enforcement of penalties.

Many surveys have demonstrated that the public are generally aware that it is unacceptable to litter but continue to do so anyway, for a range of reasons including:

- Personal disposition towards littering (e.g., embedded values, attitudes, knowledge, awareness, personalities, lifestyles) and social norms: we do what others do and if they litter or flytip without consequences, it becomes a signal that it is okay to do so. If litter already occurs in a location, there is a greater risk of more littering[171]. It should, however, be noted that while there is a proportion of society who litter there is a large volunteer community in Scotland that helps to tackle litter via litter picks etc.

- Convenience: One in three litterers say they did so because there was no bin nearby. One in five say it was due to sheer laziness. Immediate personal circumstances also influence behaviour, for example, being under the influence of alcohol, in a rush, in someone else’s area and unlikely to be seen or caught.

- Unclear responsibility: Although most people agree that it is our own responsibility to take care of our rubbish, there are situations when we think it is more okay to litter (e.g., at a concert where we know someone else is cleaning up afterwards). ‘Beneficial’ factors also play a role, for example, some individuals may think it provides jobs for cleansing staff, revenue raised from FPNs, provides food for wildlife, food or peels are biodegradable.

Ultimately the reason why someone chooses to litter or flytip is complex with multiple factors often at play and being dependent on the person, the situation and the litter/waste type. Changing littering and flytipping behaviour is not as simple as changing a habit[172]. In recent years, society has seen significant changes in behaviour such as not wearing seat belts or using a mobile phone whilst driving. As outlined by a KSB LEQ Network Officer with over 14 years’ experience, litter in particular differs to these other now illegal acts in that it is a thoughtless, moment in time act[173]. For a lot of people littering, it is not a conscious decision as using a mobile phone whilst driving or not wearing a seatbelt are.

Because human behaviour is such a critical factor in addressing environmental issues, many researchers have studied what motivates and sustains certain behaviours and how those principles can be used to persuade people to act differently. Human behaviour is not easy to decipher, it is complex and multifaceted. There are a number of key factors that influence how and why some people act and why others do not, with many of these factors being related to individual motivations as well as social and the environmental context. The belief that knowledge alone leads to an attitude of change and, subsequently, to behaviour in favour of the environment, has been repeatedly discredited as overly simplistic.

The role of infrastructure

Motivations are commonly financial as it is cheaper to illegal dump waste rather than dispose it through the appropriate, responsible channels. In some cases, people may find the cheapest option is hiring a fly-by-night contractor to take away their waste[174]. As outlined earlier, householders tend to be unaware of their duty of care[175]. In some cases, people are generally unaware of the cost of correctly disposing of different items and the services available to them (e.g., local authority bulky uplifts). It is also often cheaper and easier to dump bulky items (e.g., sofas) on the street than to take it to the recycling centre, particularly if members of the public do not have suitable private transport[176]. People believe that they will not get caught so they are not deterred.

The key role infrastructure plays was witnessed during the COVID-19 pandemic when services, including access to HWRCs, were reduced. In England a perceived increase in small scale flytipping was attributed by some local authority workers to waste infrastructure induced behaviour change, resulting in more flytipping[177].

Alternative solutions for the correct disposal of special waste have been implemented in the city of Barcelona. ‘Special waste’ includes: furniture and junk collection; dead animals collection; Roba Amiga Programme, (“friendly clothing”, an employment project addressed at people with special difficulties which consists of reusing old clothes and accessories in good conditions); collection of bags of debris generated from building renovations; fibrocement and asbestos collection.[178]

Proximity points have been arranged specifically for the commercial and service sector to try and avoid the use of street containers/bins. For example, greengrocers and small retailers who used to leave their crates next to bins are now asked to deliver plastic and wooden crates to “green spots” located on the city’s periphery. To ensure users are well informed about the available options for correctly disposing their waste and to reduce non-compliance, the City Council of Barcelona provides detailed information on its website.

Case Study: Behaviour change signage in Cornwall[179]

Signs are used to discourage people from littering by making people think about their behaviour. A study by The Behaviour Change Cornwall ‘Living Lab Looe’ explored the correlation between different types of signage and how much litter was dropped by individuals. Their results determined whether certain types of signs worked better to ‘nudge’ people to recycle than others.

Signs which promote the feeling that you are being watched (e.g. using an image of watching ‘eyes’) and which acknowledge the negative effects which litter has on the environment and wildlife (e.g. using an image of marine life) appeared to work well ); signs which included a message about positive social norms and expectations (e.g., ‘9 out of 10 people use a bin’, or ‘be a hero’) also appeared to be effective. This suggests framing litter as a social behaviour and as something connected to positive impacts may play a role in reducing litter and influencing social attitudes.

Signs which promoted community values (e.g. ‘Looe is a strong community’) appeared to have less impact on littering in comparison to other signage, according to the study. This could be because if people are not from the area (e.g. tourists) or do not have a strong connection to the place they are in, this form of messaging will not be effective. The study also suggested that the threat of a fine or which included negative messaging (e.g. ‘1 in 10 people drop litter’) were less effective in reducing litter compared to the other signs. The study concludes that ‘[s]ocial influence and targeted salience signs can be powerful tools for encouraging a reduction in plastic waste’, and that signage can form part of wider, long-term strategies for reducing litter and supporting pro-environmental behaviours.

Education and awareness

The new National Litter and Flytipping Strategy for Scotland consultation found that there was a high level of support to develop and adopt a national anti-litter campaign that addresses the behaviours and attitudes of people who litter, to hold them accountable. Suggestions put forward included focusing on educating the public, especially young children, about the impacts, risks and consequences of littering.

There was also support for a national anti-flytipping campaign or single information point advising on the disposal of commonly flytipped materials. Those responding to the consultation felt that these actions would help educate the public, outlining how to properly dispose of waste, what materials can be disposed, where and at what cost. Early years education was also identified as a key lever, to ensure behaviour change is targeted from a young age. Priority topics identified for intervention included showing the damage that flytipping can cause to wildlife, providing details on the locations and opening times of waste disposal centres, outlining penalties and sanctions as well as guidance on how to report flytipping. The case study on behaviour change signage in Cornwall outlines the role differing signage can have on littering behaviours.

Society as a whole has become desensitised to the issue of litter specifically, accepting it as normal part of life. As well as targeting those who actively litter and flytip, education and awareness needs to target those who do not carry out these illegal behaviours to empower everyone to call out undesirable behaviour when they see it and not just accept it or see it as something that cannot be changed.

Organisations including Zero Waste Scotland, KSB and SEPA regularly issue campaigns and public information to encourage the public to not litter or flytip and use waste disposal services. However, despite this ongoing action litter and flytipping remains a key problem in Scotland, showing the complexities associated with enforcement, education and awareness and behaviour change.

Contact

Email: nlfs@gov.scot

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback