Litter and flytipping offences - enforcement review: final report

We commissioned this research report in 2022 and it was completed by Anthesis in autumn 2023. This project aimed to review the current enforcement model in Scotland and offer recommendations to strengthen that enforcement.

Enforcement Models

What is the current situation in Scotland?

A strong and effective enforcement model has the potential to reduce and manage occurrences of both litter and flytipping. A recent report commissioned by Scottish Government into the cost of litter and flytipping (update to 2013 report) found that for litter, enforcement costs were the second largest cost component of local authority litter costs (£5,224,629, 11% of total spending)[30]. Enforcement costs were also the second largest cost component of local authority flytipping costs (£2,355,413, 19% of total spending)[31].

In Scotland the main legislation governing littering and flytipping is the Environmental Protection Act 1990[32]. Under this Act, littering, flytipping and, the passing of waste by a business to an unauthorised waste carrier are criminal offences. Local authorities and other duty bodies have a statutory duty to keep their land clear of litter and refuse. The standards required under these statutory duties are set out in the Code of Practice of Litter and Refuse (CoPLaR)[33]. Appendix 3 – Code of Practice on Litter and Refuse (CoPLaR) duties outlines the bodies responsible for the duties required under CoPLaR.

What are the different penalties?

Fixed Penalty Notice (FPN) – a notice giving an individual the opportunity to discharge any liability to conviction for that offence by payment of a fixed penalty[34]. Generally used for minor offences, often around anti-social behaviour, and can be issued on the spot. The recipient can refuse the offer of the FPN and opt for the matter to be dealt with in court instead of paying the fine.

Fixed Monetary Penalty (FMP) – financial penalty that can be imposed by SEPA for a specified offence. There are three levels prescribed in Scotland that SEPA can issue - £300, £600 and £1,000. These are set for relevant offences in The Environmental Regulation (Enforcement Measures) (Scotland) Order 2015[35]. Before an FMP is issued, there must be sufficient evidence that the responsible person has committed the offence to which the penalty relates. An FMP is a civil sanction and no conviction is registered. There is a right of appeal where a person disagrees with the imposition of an FMP and, as with all civil sanctions, SEPA is obliged to follow the Lord Advocate’s Guidelines.

Variable Monetary Penalty (VMP) – a variable financial penalty, guidance on the use of which is set out in the Lord Advocate’s Guidelines to SEPA[36]. In Scotland, the maximum amount for most offences is the maximum fine amount for a conviction by summary conviction for the particular offence and is not the same for all environmental offences. Where there is no statutory maximum fine for the offence for an offence on summary conviction in question then, the maximum penalty SEPA may impose is £40,000. The minimum VMP likely to be imposed by SEPA is £1,000. Before imposing a VMP, SEPA must be satisfied there is enough evidence that the responsible person has committed the offence.

One of the key aspects of a VMP is that they are likely to be used for ‘relevant offences at the upper end of the scale of offending, but which do not require to be reported to Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service (COPFS) for consideration of prosecution’[37]. SEPA can, of course, liaise with COPFS to decide whether referral for consideration for prosecution is more appropriate. As is the case for an FMP, acceptance of a VMP does not result in a conviction, and a person can appeal the imposition of a VMP.

Littering

Currently the FPN for littering is £80. Alleged offenders are required by law to provide their name and address. The FPN could be raised by secondary legislation to a maximum of £500[38]. The key legislation for littering in Scotland is Section 87 of the Environmental Protection Act 1990[39].

Penalties can be issued by the police, local authorities, and certain public bodies (Loch Lomond and the Trossachs National Park Authority). The Lord Advocate’s guidelines provide assistance, including the use of FPNs, to police officers[40].

Local authorities are responsible for responding to, and clearing, public land. Statutory undertakers such as Network Rail, Scottish Canals and educational institutions also have responsibilities to clear litter from public areas under their control (Appendix 3 – Code of Practice on Litter and Refuse (CoPLaR) duties).

Flytipping

Currently the FPN is £500 for flytipping. Offenders are required by law to provide their name and address. The FPN cannot be raised by secondary legislation to a higher amount. [41]. SEPA has civil sanction powers and can issue FMPs and VMPs (not FPNs), as outlined in Flytipping – SEPA’s role.

FPNs can be issued by the police, local authorities, and certain public bodies. The Lord Advocate’s guidelines provide assistance to police officers regarding the approach to be taken in connection with the liberation of offenders (including the use of FPNs) by Police Scotland[42]. Powers to issue FPNs were extended to include Loch Lomond and the Trossachs National Park Authority, one of Scotland’s two current national parks, in 2015 as a measure to deter potential incidences of flytipping. In some cases, National Park Rangers will collaborate with the relevant local authority (e.g., Stirling Council) to carry out a joint investigation, identify the alleged offender and issue the FPN[43]. The police have powers to seize vehicles used for flytipping.

As outlined, a number of different bodies have responsibilities for flytipping in Scotland. Local authorities are responsible for responding to, and clearing, public land. Investigating incidents of flytipping is a joint responsibility of local authorities and where required SEPA and Police Scotland. This applies to private land as well as public land. However, not all flytipping cases on private land will be investigated. Some local authorities may uplift waste from private land although this is not always the case and is not always as simple as it is on public land. In addition, flytipping can poses a particular challenge on private land, with stakeholder engagement suggesting that private landowners and land managers are often particularly adversely affected as they can often be left paying the significant cost to clear and dispose of any material.

Stakeholder insights gained as part of the project suggest that the way in which local authorities approach flytipping varies, often due to differing priorities but also as a result of incidences of occurrences being more heavily prevalent in the city council regions such as Glasgow[44] and Edinburgh[45]. This is explored later in the project.

The use of enforcement action

COPFS is Scotland’s prosecution service and death investigation authority[46]. They receive reports about crimes from the police and other reporting agencies and then decide what action to take, including whether to prosecute someone. They make decisions independently and in the public interest, and follow the process set out in the Prosecution Code[47] to make decisions[48].

The Scottish Courts and Tribunals Service (SCTS) is an independent body corporate established by the Judiciary and Courts (Scotland) Act 2008. Its function is to provide administrative support to Scottish courts and tribunals and to the judiciary of courts, including the High Court of Justiciary, Court of Session, sheriff courts and justice of the peace courts, and to the Office of the Public Guardian and Accountant of Court[49].

The COPFS Prosecution Code[50] provides criteria for decisions. In considering the action to be taken in relation to reports of crime the prosecutor must take account of both legal and public interest considerations. In general, it is expected that reporting agencies will attempt to secure compliance by utilising their existing powers of enforcement. Reporting cases to the Procurator Fiscal will be seen as a last resort. The Prosecution Code covers evidential considerations including[51]:

- Sufficiency of evidence – the Procurator Fiscal must be satisfied that there is sufficient admissible evidence to justify starting proceedings. This means (in most cases) that there must be corroboration (evidence from at least two separate sources to establish that the crime was actually committed and that the accused was the perpetrator).

- Admissibility – in considering the evidence, the prosecutor will assess whether, having regard to the rules of evidence, a court will allow the evidence to be considered in the case.

- Reliability – while there may be sufficient, admissible, evidence to justify criminal proceedings, consideration must also be given to the reliability and quality of that evidence.

- Credibility – the assessment of the credibility of evidence is ultimately a matter for the court. However, there may be doubt about the credibility, or truthfulness, of a witness’s evidence.

Other areas under the “criteria for decisions” cover legal considerations (domestic versus international law) and public interest considerations. When it comes to “options”, this can be[52]:

- Prosecution – for many cases, prosecution will be the preferred option, assuming that there is sufficient evidence to justify proceedings. However, the prosecutor will have regard to factors such as the gravity of the offence, the offender’s record and the likely penalty in the event of conviction.

- Alternative to prosecution – no proceedings, no proceedings meantime, warning by the Procurator Fiscal, fiscal fine, diversion from prosecution and referral to the Scottish Children’s Reporter.

When COPFS receive a litter or flytipping report (in the form of a standard prosecution report) from Police Scotland or a local authority it is completed on a standard template outlining the nature of the offence, the date, and, where possible, any previous convictions. In all reports (not specific to litter and flytipping) the prosecutor would look for how the case “proves” (i.e., is there sufficient evidence, as detailed above). For littering, evidence does not need to be corroborated, the evidence of one witness, who can speak to the fact the offence of littering was committed, and can identify the person responsible, is enough. For flytipping, evidence that the offence was committed, and identification of the perpetrator must be corroborated, meaning that there must be two separate sources of evidence. Where the report does not contain sufficient evidence, the case cannot proceed[53].

If a FPN is rejected or not paid within the notice period, the authority that issued the notice can refer the case to COPFS who will decide if further action will be taken, and if so, whether it will be an alternative to prosecution, or prosecution.

If a case goes to court someone convicted of littering could be fined up to £2,500, while someone convicted of flytipping on summary conviction could be fined up to £40,000 and/or imprisoned for up to 6 months, with higher penalties where the conviction is on indictment[54].

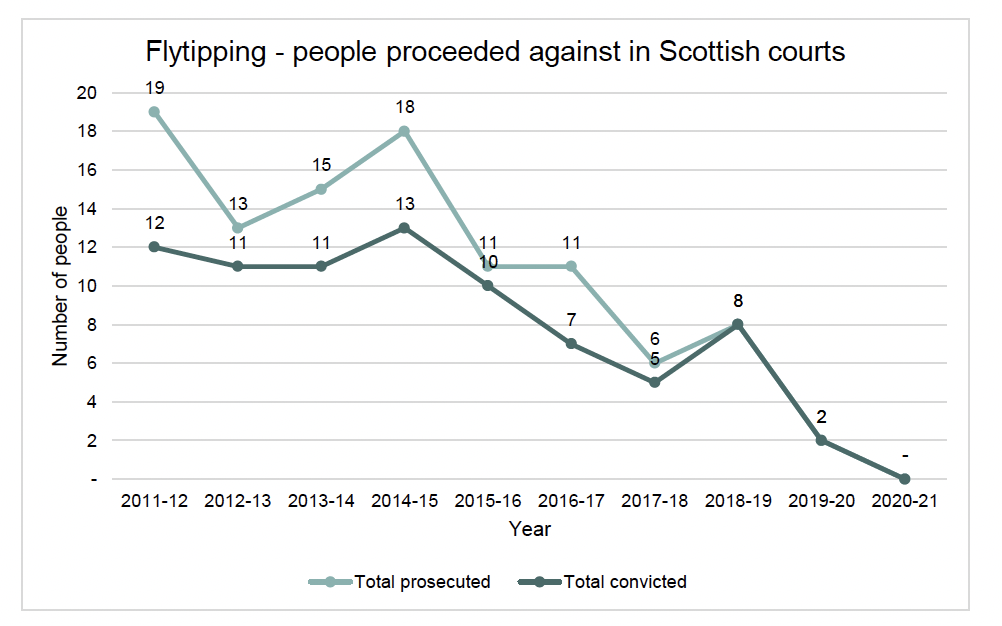

Figure 1 Number of people proceeded against between 2011/12 and 2020/21 in the Scottish courts for flytipping offences (Scottish Government, 2022).shows that the total number of people prosecuted and convicted for flytipping offences in the Scottish courts has decreased from 19 prosecuted and 12 convicted in 2011/12 to 2 prosecuted and 2 convicted in 2019/20. The 2020/21 data is likely to be affected by the COVID-19 pandemic and consequent court closures. The 2021/22 data is not yet available. There has been a general downward trend in the number of people prosecuted and convicted for flytipping offences over the past ~10 years and numbers are generally very low. Many cases prosecuted did, however, end in a conviction. A 2023 FOI release showed that since 2016, of the 375 flytipping reports received by the Crown Office, 59 were taken to court (15.7%)[55].

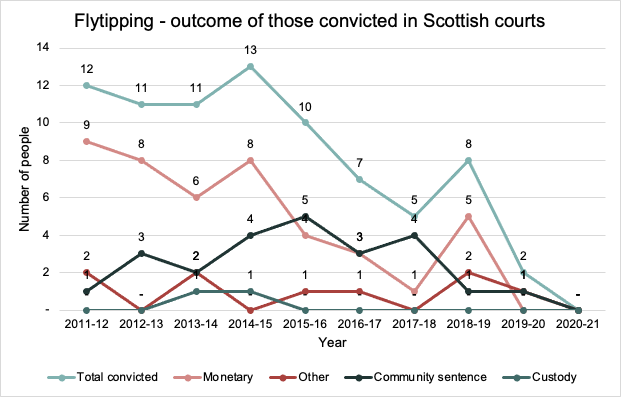

Figure 2 Outcome of convictions for flytipping offences in the Scottish courts between 2011/12 and 2020/21 (Scottish Government, 2022). shows that of those convicted, a range of sentences were used. Monetary and community sentences were the most used punishments, with custodial sentences only being used twice.

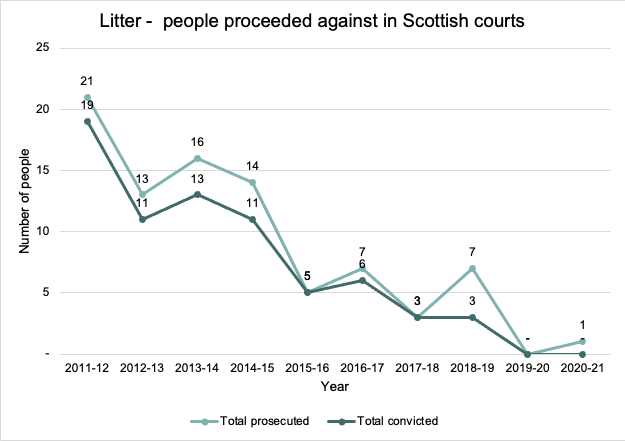

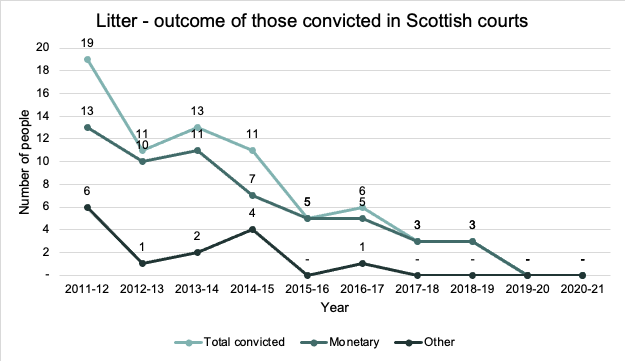

Like flytipping, the number of prosecutions and convictions for litter has decreased between 2011/12 and 2019/20, going from 21 prosecuted and 19 convicted in 2011/12 to zero prosecutions and zero convictions in 2019/20 (Figure 3 Number of people proceeded against between 2011/12 and 2020/21 in the Scottish courts for litter offences (Scottish Government, 2022). Most litter cases prosecuted ended in a conviction. For those litter prosecutions that ended in a conviction, a large proportion received a monetary sentence, with the remaining convictions receiving an “other” outcome (Figure 4 Outcome of convictions for litter offences in the Scottish courts between 2011/12 and 2020/21 (Scottish Government, 2022).

Please refer to Appendix 4 – People prosecuted and convicted by Local Authority for litter and flytipping. For details of the number of people prosecuted and convicted between 2011/12 and 2020/21, split by local authority (for both of litter and flytipping). Some enforcement bodies interviewed as part of the project highlighted that prosecutions and convictions for litter and flytipping offences are lower than they feel they should be. While the low number of prosecutions and convictions can be seen in Figures 1 to 4 it is not simply a case that prosecutors are not progressing cases passed to them. As outlined above if the report passed to COPFS does not contain sufficient evidence then the case cannot procced, with evidence and the quality of evidence being a significant barrier to the use of enforcement powers[56].

There are also a number of non-court disposal routes used for litter and flytipping offences. Both the police and Procurator Fiscal can issue a “direct measure” for an alleged offence. If the alleged offender accepts the “direct measure” the case will not go to court, and the offender will not get a criminal conviction.

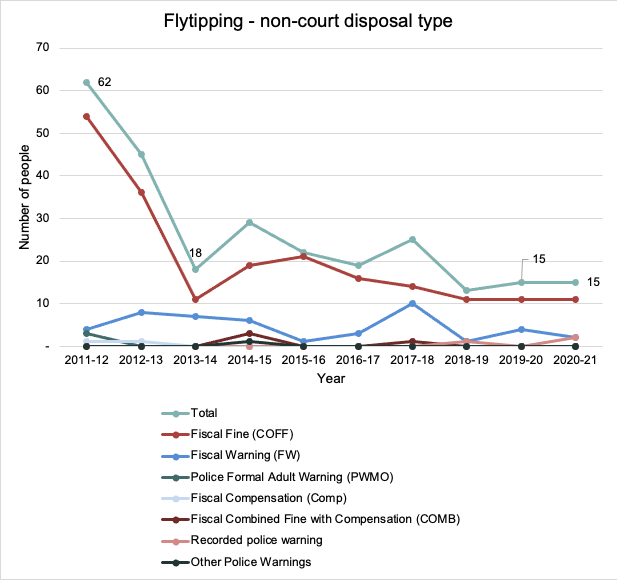

Figure 5 Number of direct measures (by type) issued for flytipping offences between 2011/12 and 2020/21 (Scottish Government, 2022). refers to the non-court disposal routes that can be used for flytipping. A total of 62 direct measures were issued in 2011/12. This rapidly decreased to 18 in 2013/14 and has remained around that level since. In 2019/20 (pre-COVID-19 year used to ensure the data is representative) 15 direct measures were issued. The method most used between 2011/12 and 2019/20 is a Fiscal Fine. The second most used disposal measure is a Fiscal Warning.

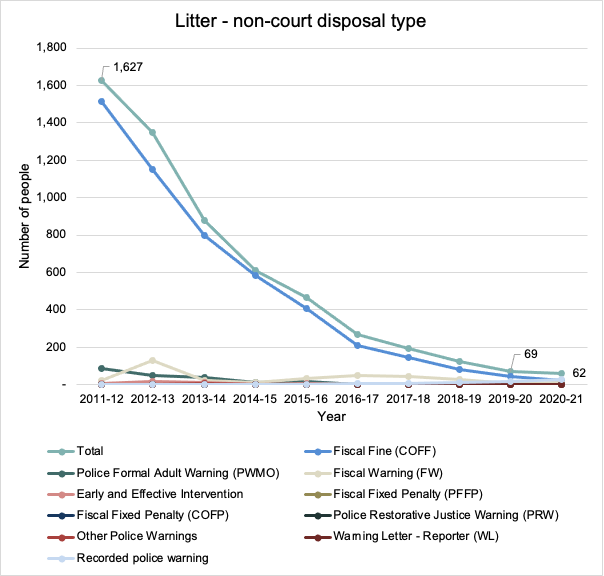

In terms of litter offences, a total of 1,627 disposal methods were used in 2011/12 (Figure 6 Number of direct measures (by type) issued for littering offences between 2011/12 and 2020/21 (Scottish Government, 2022).). This has steadily decreased over the years, with only 69 non-court disposals being used in 2019/20. The most common method used is a Fiscal Fine. Other measures such as a Fiscal Warning have been used minimally.

When COPFS receive a report, and it meets all the sufficiency requirements, they action it[57]. While the number of prosecutions, convictions and non-court disposal routes has decreased over the last 5 years, this does not simply indicate that less cases are taken forward, as it is directly linked with the number of reports passed to COPFS in the first place and also if the reports prove (i.e., have sufficiency evidence to be actioned).

Making a correlation between enforcement activity and cases of litter and flytipping is challenging. While the LEAMS audit suggests that the number of locations with unacceptable amounts of litter has increased since the previous year, for flytipping a clear understanding of trends in instances cannot be determined. This is likely due to the multiple channels and organisations recording data separately and the lack of reporting of instances on private land. In addition to this, the low number of cases passed to COPFS and eventually prosecuted, and a lack of reporting on FPNs issued makes it difficult to assess whether enforcement activity plays a role in deterring litter and flytipping.

Nevertheless, evidence and feedback from key stakeholders suggests instances of litter and flytipping are increasing but the number of cases prosecuted or FPNs issued is either decreasing or static. However, as not all local authorities make data on the number of FPNs issued publicly available, it is challenging to understand the full use of existing enforcement powers.

Flytipping – SEPA’s role

SEPA’s powers to issue civil sanctions are given effect by the Environmental Regulation (Enforcement Measures) (Scotland) Order 2015[58]. SEPA can issue FMPs of £600 for flytipping. This could be increased by secondary legislation to £1,000 were the offence to be reclassified as “high”, or, up to a maximum of £2,500 if the “high” amount were then to be adjusted to the currently statutory maximum. SEPA can also issue a VMP of up to £40,000. SEPA do not issue FPNs. While an unpaid FPN can be progressed through the courts, this is not the case for FMPs and VMPs. Once an FMP or VMP has been served by SEPA the same offence cannot be referred to the Procurator Fiscal for prosecution. If FMPs or VMPs are unpaid, then these are recovered by way of civil debt recovery.

The Lord Advocate’s Guidelines to SEPA[59] outlines the use of enforcement measures under the Regulatory Reform (Scotland) Act 2014 (which are those given effect in the 2015 Order), while SEPA’s Guidance on the use of enforcement action[60] provides guidance directed at any person (including a business) carrying out any activity where SEPA is the enforcing authority and explains how SEPA will use enforcement action (including FMPs and VMPs).

SEPA’s main focus is large-scale illegal waste dumping/flytipping, while smaller scale incidents are dealt with by local authorities. SEPA works in partnership with other bodies including Police Scotland and local authorities (and UK agencies such as the Joint Unit for Waste Crime) to respond to, and prevent, large scale industrial instances of flytipping in communities.

SEPA can also issue FMPs and VMPs for related offences such as failing to comply with the commercial duty of care, burning of waste, and not being a registered waste carrier. These penalties can be applied to both individuals and businesses. The number of FMPs issued by SEPA for related offences are outlined in Table 2. Since 2016, 1 FMP has been issued for flytipping offences. FMPs can be issued to both individuals and organisations/companies where there is suitable and robust evidence.

Offence |

Number of FMPs Issued |

Value (per FMP) |

|---|---|---|

Depositing controlled waste when no waste management licence authorising such disposal was in place (Flytipping) |

1 |

£600 |

Failure to be registered when transporting controlled waste |

10 |

£300 |

Disposing of controlled waste by burning |

9 |

£600 |

Failure to furnish SEPA with copies of documents requested in a notice under section 34(5) of the Environmental Protection Act 1990 and Regulation 6 of the Environmental Protection (Duty of Care) (Scotland) Regulations 2014 |

1 |

£300 |

Other FMPs are likely in the process of being considered/issued |

||

The distinction between sites with significant flytipping/dumped waste and illegal landfills is important to consider. At some point the activity is expected to cease to be considered as flytipping, instead being classified as an illegal waste operation. Illegal waste operations, due to their scale, duration, and risk, are SEPA’s focus.

The issue of organised crime groups (OCGs) illegally burying waste across Scotland was highlighted by current affairs series Disclosure in January 2022[61]. The investigation found that OCGs are using threats and intimidation against landowners who refuse to allow waste to be buried on their land. It was also highlighted by an insider from a criminal network that dumping waste had become as profitable as the drug trade. The legitimate disposal of waste is relatively expensive due to the cost of authorisations, gate fees and, where relevant, landfill tax. Criminal gangs that avoid these costs have a significant competitive advantage over legitimate traders.

The investigation also found that crime gangs from the north of England had multiple sites across Scotland, with waste being driven up in lorries. Another tactic used is to fill old lorry trailers with waste and then abandon them in lay-bys and quiet streets. In the 15 months prior to the programme, 12 trailers were found across central Scotland, all containing household and construction waste[62].

Serious organised crime has a significant impact (The Environmental Services Association last year estimated that criminality in the trade was costing the UK taxpayer more than £1bn a year[63]). Illegal waste sites operate without a permit, are organised, and involve multiple loads of waste being treated, stored, or disposed of. These activities may be known to the landowner/occupier and run as a business. Such situations are more complex and should not be considered flytipping when assessing flytipping statistics.

What does enforcement look like in other UK nations?

In addition to reviewing the current enforcement model in Scotland, the project looked at England and Wales to assess how different models, methods and actions impact litter and flytipping occurrences and enforcement effectiveness. It was challenging to draw direct comparisons between the countries reviewed due to differing models (e.g., level of fines) and the way in which data is recorded, but the benchmarking provided some scope for comparison. A high-level overview of the fines used across Scotland, England and Wales is outlined in Table 3.

Table 3 Overview of fines used for litter and flytipping offences in Scotland, England and Wales

Country: Scotland

Litter

FPN of £80

If the fine is not paid and the offender is prosecution and convicted, the offender could be fined up to £2,500

Flytipping

FPN of £200

If the fine is not paid and the case goes to court the offender is liable to a fine of up to £40,000 with the possibility of a custodial sentence on summary conviction, with higher maximum penalties on indictment.

FMP of £600 (SEPA only)

VMP of up to £40,000 (SEPA only)

Country: England

Litter

FPN of £65 to £150

If the offender is prosecuted and convicted in court, the fine could rise to £2,500

In England, local authorities can set the specific FPN value, as long as it is within the ranges set in law (outlined above)

Flytipping

FPN of £150 to £1000 for small scale flytipping

The maximum fine for flytipping that can be issued by the courts is unlimited, with the possibility of a custodial sentence.

In England, local authorities can set the specific FPN value, as long as it is within the ranges set in law (outlined above)

Country: Wales

Litter

FPN of £75 to £150

The maximum fine that can be imposed by the courts for littering is £2,500.

In Wales local authorities can set the specific FPN value, as long as it is within the ranges set in law (and outlined above)

Flytipping

FPN of £150 to £400

The maximum fine for flytipping that can be issued by the courts is unlimited, with the possibility of a custodial sentence.

In Wales local authorities can set the specific FPN value, as long as it is within the ranges set in law (and outlined above)

England

Flytipping

For the year 2021/22, local authorities in England recorded 1.09 million flytipping incidents, a decrease of 4% from the 1.14 million reported in 2020/21[64]. Around 61% of flytipping incidents involved household waste, with the most common place for flytipping to occur being highways (pavements and roads).

Total incidents involving household waste were 671,000 in 2021/22, a decrease of 9% from 740,000 incidents in 2020/21[65]. While there has been a decrease in the number of flytipping instances from 2020/20 to 2021/22 it is noted that the data only covers cases dealt with by local authorities (and not those on private land) so does not give a full overview of the issue. There were 91 incidents of large-scale, illegal dumping dealt with by the Environment Agency in 2021/22[66]. A report for Material Focus estimated that approximately 1.82 million tonnes of waste fell outside the legitimate system in 2019/20 in England, due to flytipping on public land, or being taken to an illegal waste site[67].

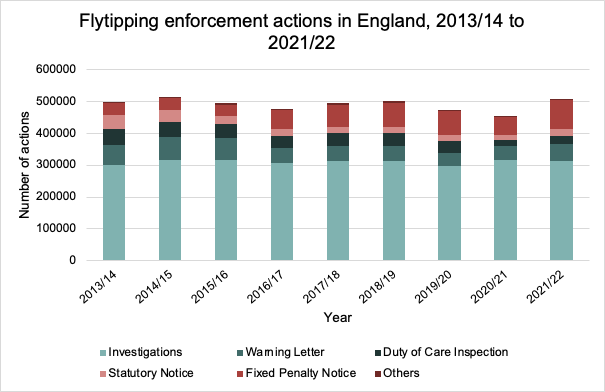

In England, local authorities carried out 507,000 enforcement actions in 2021/22, an increase of 52,000 actions (11%) from 455,000 in 2020/21 (Figure 7 Flytipping enforcement actions in England from 2013/14 to 2021/22 (Defra, 2023).

The ‘other’ category refers to the sum of stop and search, vehicles seized, formal caution, prosecution and injunction.). The number of FPNs issued was 91,000 in 2021/22, an increase of 58% from 57,700 in 2020/21. This was the second most common action after investigation and accounted for 18% of all actions in 2021/22. The number of court fines issued nearly tripled from 621 in 2020/21 to 1,798 in 2021/22 (190%), with the value of total fines more than doubling to £840,000[68] (the value was £330,000 in 2020/21). It should be noted that the 2020/21 reporting period covers the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic where some local authorities could not maintain key services and courts were unable to take action which may have influenced occurrences and enforcement action.

While the data outlined above shows a slight decrease in the number of recorded flytipping incidents and increase in enforcement actions in England between 2020/21 and 2021/22 it is unlikely increased enforcement alone played a role in reducing the number of incidents. Improved reporting, changes in demographics, public perception and council priorities (and possibly COVID-19) are all likely to have had in influence. In addition, between 2019/20 and 2020/21 there was an increase in cases but a decrease in the number of enforcement actions, the opposite trend seen between 2020/21 and 2021/22, again likely a result of multiple factors.

It is also impossible to compare the data gathered in England to Scotland and assess whether trends in England were also observed in Scotland due to the lack of national reporting of flytipping incidents in Scotland. It is also not possible to compare the number of enforcement actions carried out by local authorities in Scotland due to local authorities in Scotland not being required to report on enforcement actions.

The ‘other’ category refers to the sum of stop and search, vehicles seized, formal caution, prosecution and injunction.

In England, flytipping data is based on incidents and actions reported through Waste Data Flow[69]. The intention is to capture all flytipping incidents and enforcement actions taken by local authorities in response to flytipping incidents. There is a level of discretion in applying the reporting guidance which can lead to some differences in how local authorities record incidents. The nature of flytipping means that there can be relatively high variation between years and between local authorities.

Maximum court sentences for flytipping are set out in the Environmental Protection Act 1990[70]. There is no maximum fine set out in law for unlawfully depositing waste under Section 33 of the Environmental Protection Act[71] (unlike in Scotland where this is £40,000 on summary conviction for the offence). Sentencing is a matter for the independent courts. An offender is liable:

- On summary conviction in the magistrates' court, to imprisonment for a term not exceeding 6 months, an unlimited fine or both.

- On conviction on indictment in the Crown Court, to five years imprisonment, an unlimited fine or both.

Year |

Fines Issued |

Absolute or Conditional Discharge |

Other (successful outcomes) |

Community Service |

Custodial Sentence |

Cases Lost |

Total Prosecutions |

Successful Prosecutions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

2012/13 |

1839 |

165 |

106 |

16 |

18 |

23 |

2170 |

98.80% |

2013/14 |

1685 |

183 |

56 |

19 |

10 |

36 |

2002 |

97.60% |

2014/15 |

1492 |

128 |

95 |

35 |

21 |

31 |

1810 |

97.80% |

2015/16 |

1838 |

136 |

67 |

32 |

18 |

44 |

2135 |

97.90% |

2016/17 |

1318 |

93 |

81 |

26 |

28 |

56 |

1571 |

98.40% |

2017/18 |

1802 |

67 |

112 |

45 |

25 |

58 |

2108 |

97.30% |

2018/19 |

1659 |

80 |

109 |

40 |

26 |

101 |

2005 |

95.50% |

2019/20 |

1657 |

58 |

95 |

44 |

41 |

50 |

1930 |

98.20% |

2020/21 |

621 |

33 |

36 |

15 |

5 |

25 |

721 |

98.50% |

2021/22 |

1798 |

55 |

63 |

30 |

20 |

37 |

1959 |

100.40% |

Those convicted of flytipping may also have to pay legal costs and compensation, which can greatly increase the financial implications of illegal dumping. In addition, under the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002[72], offenders can have assets frozen and confiscated. Table 4 shows the outcome of flytipping prosecutions in England between 2012/13 and 2021/22.

In 2016 local authorities in England were given powers to issue FPNs of between £150 and £400 for small-scale flytipping offences under section 33ZA of the Environmental Protection Act 1990 which was added by the the Unauthorised Deposit of Waste (Fixed Penalties) Regulations 2016[73] (the FPN for flytipping in Scotland is £500). The FPN can be served as a criminal penalty in lieu of prosecution for a criminal offence and is not a civil penalty[74]. Prior to this, local authorities issued flytippers with FPNs in relation to littering, duty of care or anti-social behaviour. The Government has also provided local authorities with powers to stop, search and seize vehicles of suspected flytippers.

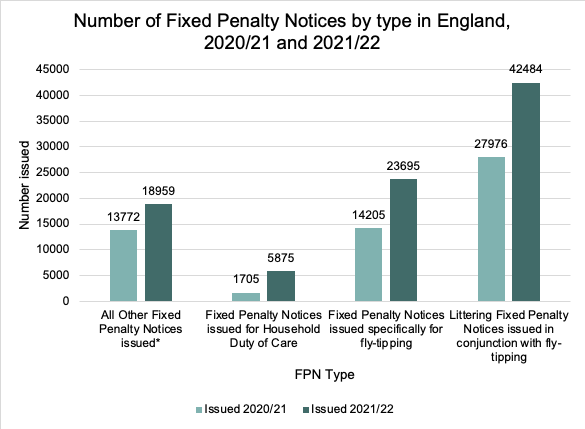

Further enforcement powers were given to local authorities in January 2019. They can now issue FPNs for breaches of householder duty of care, in cases where householders pass their waste to an unlicensed waste carrier. Figure 8 Number of Fixed Penalty Notices by type in England, 2021/22, compared to 2020/21 (Defra, 2023). shows the number of FPNs issued by type in 2021/22 compared to 2020/21. There has there been an increase in all types of penalties issued.

The UK Government has now increased the upper limit on fines for flytipping from £400 to £1,000 and is also supporting local authorities in handing out more fines to “disrespectful offenders”[75]. In addition, it was proposed that affected communities and victims of anti-social behaviour may get a say in deciding what type of punishment or consequences offenders should face, alongside input from local police and crime commissioners[76]. The UK Government may also consider publishing league tables for local authorities based on their flytipping performance[77]. Defra also announced new grants totalling £775,000 for local authorities to support projects that reduce flytipping[78]. 21 local authorities will benefit from the grants, with schemes including roadside CCTV and social media campaigns. These grants build on a first round of projects which provided £450,000 to 11 local authorities in 2022.

‘Flytipping’ is a broad term used widely with a recognised common public perception on meaning. To establish a clear line with partners the Environment Agency uses the term ‘illegal dumping’ to differentiate between the Environment Agency’s role and that of a local council[79]. Larger and more serious cases of flytipping are therefore referred to as ‘illegal dumping’.

Local authorities are responsible for investigating and clearing waste on public land[80]. They can also investigate incidents on private land. Where the waste is deposited on private land (open land or within a building), responsibility for dealing with the waste rests with the landowner. The local authority may need to contact the Environment Agency if the illegally dumped waste is more than 20 tonnes, is more than 5 cubic metres of fibrous asbestos or 75 litres of potentially hazardous waste in drums or containers or where it is possibly linked to criminal business activities or organised crime[81]. Similarly to SEPA, the Environment Agency can investigate and take enforcement action if the incident is large-scale, serious, organised illegal dumping or immediately threatens human health or the environment[82]. However, they do not have a specific direct statutory duty to act. Cases taken forward are likely to be influenced by priorities, risk, and environmental impact.

The * for “all other fixed penalty notices issued” highlights that these FPNs have been served in relation to flytipping and other waste offences that are not captured by the other three categories.

In England (unlike in Scotland) local authorities have the flexibility to set the value of a FPN as long as it does not go below the minimum or over the maximum stipulated in legislation. Tower Hamlets council reported an increase in reported flytipping incidents from 4,555 in 2015/16 to 9,228 in 2018/19[83]. As a result, in 2019 they increased the FPN for flytipping to £400 (from £80), with no early payment discount[84]. Previously, the £80 fine for flytipping could be reduced to £50 if paid within 10 days. The council’s decision to increase the fine reflects more appropriately the cost of dealing with flytipping. Following the introduction of the higher fines, the number of flytipping incidences reduced from 9,228 in 2018/19 to 7,537 between 2020/2021[85]. However, a recent report has revealed that the number of flytipping incidences in Tower Hamlets is beginning to increase once again, with the number of incidences occurring now standing at 8,199 in the year to March 2022[86].

Similarly, North Hertfordshire Council[87] increased the FPN for flytipping to £400 (reduced to £300 if paid within 10 days). The fine was previously £300 (reduced to £200 if paid within 10 days). Prior to the increase in the FPN North Hertfordshire saw incidents triple over the last 10 years. As a result of enforcement work and education flytipping incidences reduced by 9.5% from April 2021 to January 2022[88].

While the examples of Tower Hamlets and North Hertfordshire Council increasing fines for flytipping show a decrease in flytipping incidences in the short-term it is challenging to quantify if increasing fines has a long-term impact given the increase in fines has only been made recently, and in the case of North Hertfordshire Council was concurrent with education. However, as seen by the short-term results, increasing fines for flytipping has the potential to reinforce the message that actions have consequences and ensure that the level of the fine is more aligned with the severity of the crime. This does, however, likely need to be reinforced with education and awareness.

Litter

Like Scotland (where litter is monitored via LEAMS), measuring littering in England is challenging so a dashboard of indicators covering litter on the ground, public perception, and cleanliness of public places is used. This is not a definitive measure of litter but is a good illustration of what is happening[89]. Data from 2018 to 2019 suggests 94% of sites met an acceptable standard for litter[90](the Scotland-wide street cleanliness score is outlined earlier in the report and is not comparable due to the English system being based on a smaller proportion of authority areas than the LEAMS programme). The 2018 to 2019 data found that 28% of people perceived litter to be a problem[91]. A Litter Composition Analysis Summary Report[92] published by Keep Britain Tidy provides an overview of litter compositions in England.

Section 89 of the Environmental Protection Act 1990[93] makes certain duty bodies legally responsible for keeping land, which is under their control, and where the public has access, clear of litter and refuse[94]. Roads must also be kept clean, as far as is practical. Guidance on fulfilling the duties in Scotland under this Act is provided by the Code of Practice on Litter and Refuse (Scotland) 2018[95].

Littering is a criminal offence, for which enforcing authorities in England may bring prosecutions in the magistrates’ courts or issue fixed penalties in lieu of prosecution[96]. There is no obligation on an enforcing authority to offer an alleged offender the option of paying a fixed penalty. Alleged offenders may choose not to accept or pay a fixed penalty and choose instead to defend the case in court (and possibly be subject to a higher penalty on conviction). If a littering offence is committed from a vehicle, litter authorities may issue a civil penalty which carries no criminal liability to the keeper of the vehicle from which the offence is committed[97],[98]. Guidance from Defra[99] states that the enforcing authority should be prepared to prosecute offenders for the original offence if an alleged offender does not pay a FPN, as failure to follow up on unpaid FPNs undermines their effectiveness as an enforcement tool.

In England, enforcing authorities have discretion about whether to take enforcement action, and may consider alternative sanctions or education as a more effective and appropriate tool. One approach that some authorities have found successful as an alternative to formal enforcement action is completion of a stop-smoking programme for littering cigarette ends[100].

Authorised officers have the power to issue a FPN charge of up to £150 for a litter offence (the FPN in Scotland is £80 for littering), as an alternative to prosecution. The minimum full penalty is £65[101]. If the offender is prosecuted and convicted in court, the fine could rise to £2,500[102]. In addition to issuing FPNs local authorities can serve notices on other duty bodies, businesses, landowners and occupiers that compel them to clear up litter and put in place measures to prevent the offence happening again[103].

As they do with flytipping enforcement, district councils in England (unlike in Scotland) have flexibility to set the value of a FPN for littering (as long as it does not go below the minimum or over the maximum stipulated in legislation). As an example, Bath and North East Somerset Council states anyone caught littering could be fined up to £150[104], while Newcastle City Council states that in many cases the offender will be given the option of paying a fixed penalty of £75[105] (less than the FPN in Scotland).

The receipts from FPNs for environmental offences may be retained by enforcing authorities in accordance with the relevant legislation and may only be spent in accordance with that legislation[106]. For littering this can include functions relating to litter and refuse (keeping land clear of litter and refuse, and enforcement against littering and littering from vehicles).

Wales

Flytipping

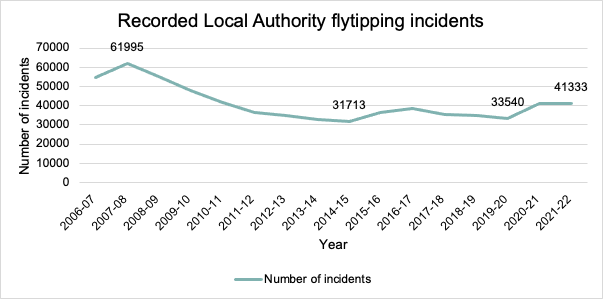

The number of cases of flytipping reported in Wales has decreased from a peak of 61,995 cases in 2007/08 to a low of 31,713 in 2014/15 (Figure 9 Recorded flytipping incidents in Wales from 2006/07 to 2021/22 (StatWales, 2022).). This does not include incidents on private land. Since then, the number of cases has been increasing with a slight fall before an increase at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, with 41,333 cases being seen in 2021/22. Local authority recorded flytipping data for April 2021 to March 2022 found that flytipping clearance in Wales was estimated to have cost £1.93 million[107]. Welsh Government is in the process of developing a Litter and Fly-Tipping Prevention Plan for Wales[108].

Like Scotland and England, local authorities are responsible for dealing with most types of small scale flytipping on publicly owned land including roads and lay-bys[109]. Natural Resources Wales investigates large scale incidents, those involving hazardous waste and those organised by gangs of flytippers. Flytipping Actions Wales[110], a partnership initiative sponsored by the Welsh Government and coordinated by Natural Resources Wales to tackle flytipping, provides direct practical support and advice on disposing of waste correctly. It is made up of 50 partners, including the 22 local authorities in Wales, the national police and fire services, the National Farmers’ Union and others.

The data is based on returns made by local authorities to the Waste Data Flow database and does not include flytipping incidents on private land.

In Wales, FPNs can be used by enforcement agencies to respond to low-level environmental crimes such as flytipping (and littering), offering an alternative enforcement option to prosecuting offenders through the courts. The Welsh Government states that “if enforced correctly they can act as an effective deterrent and change behaviour, all of which can help landowners deliver their statutory duties to keep relevant land clear of litter and refuse”[111]. Table 5 outlines the penalty for flytipping.

Offence |

Default penalty |

Minimum full penalty |

Maximum full penalty |

Minimum discounted penalty |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Littering |

£75 |

£75 |

£150 |

£50 |

Flytipping |

£200 |

£150 |

£400 |

£120 |

For ease of comparison the FPN for littering in Scotland is £80, and for flytipping is £200 |

||||

There is no obligation on an enforcing authority to offer an alleged offender the option of a fixed penalty (instead of prosecuting offenders through the courts), and equally an alleged offender may choose not to accept or pay a fixed penalty, instead choosing to defend the case in court (and risk being liable for a potentially higher penalty and costs upon conviction). Given issuing a FPN is an alternative to prosecution, if an alleged offender does not pay a fixed penalty, the enforcing authority must be prepared to prosecute them for the original offence[112].

Like in England and Scotland, maximum court sentences for flytipping in Wales are set out in the Environmental Protection Act 1990[113]. There is no maximum fine set out in law for unlawfully depositing waste under Section 33 of the Environmental Protection Act[114] (unlike in Scotland where this is £40,000 on summary conviction for the offence). An offender is liable:

- On summary conviction in the magistrates' court, to imprisonment for a term not exceeding 6 months, an unlimited fine or both.

- On conviction on indictment in the Crown Court, to five years imprisonment, an unlimited fine or both.

The data is based on returns made by local authorities to the Waste Data Flow database and does not include flytipping incidents on private land.

In its “Guidance on the use of Fixed Penalty Notices for Environmental Offences”[115], the Welsh Government clearly states its position that the failure by enforcement bodies to follow up on unpaid fixed penalty notices will undermine their effectiveness as an enforcement tool. It will discredit the use of FPNs in the locality and lead to declining rates of payment[116].

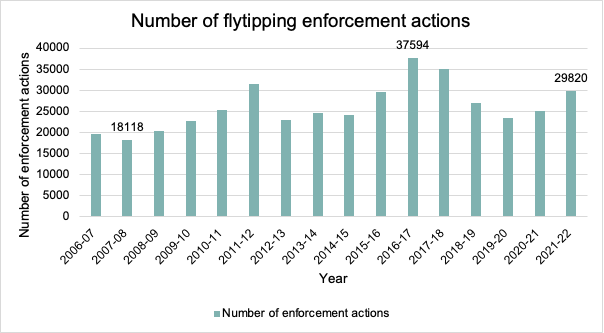

Figure 10 Total number of flytipping enforcement actions (StatsWales, 2022).

The data is based on returns made by local authorities to the Waste Data Flow database and does not include flytipping incidents on private land.

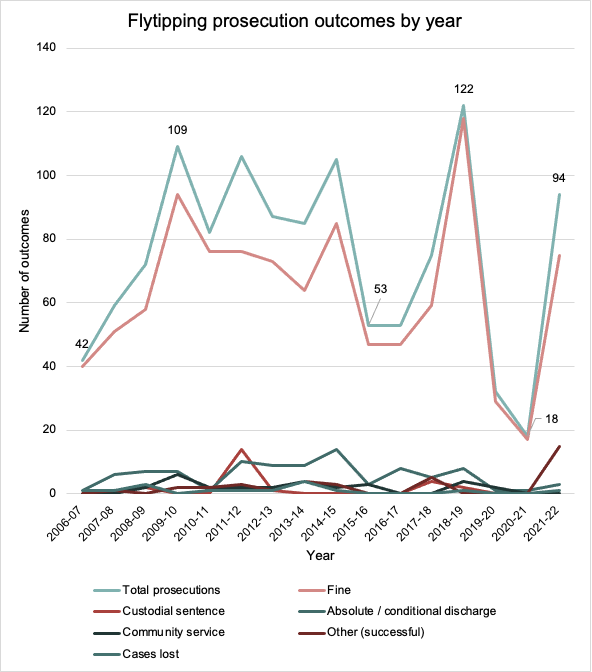

outlines the number of flytipping enforcement actions taken in Wales, with the lowest being 18,118 in 2007/08 and the highest being 37,594 in 2016/17. In 2021/22, 29,820 enforcement actions were taken. As seen in Figure 11 Flytipping prosecution outcomes by year in Wales (StatsWales, 2022)Error! Reference source not found., of the 94 prosecutions outcomes in 2021/22, 75 resulted in a fine (80%)[117].

FPNs for fly-tipping can be issued by local authorities and Police Community Support Officers (PCSOs), and persons accredited under community safety accreditation schemes (only if authorised). The Welsh Government guidance document outlines that raising revenue should never be an objective of enforcement and that when a local authority decides to set its own fixed penalty amounts (this is also possible in England, not in Scotland), these must fall within the ranges set out in the Environmental Offences (Fixed Penalties) (Miscellaneous Provisions) (Wales) Regulations 2008 (regulation 2). While Welsh local authorities can set the level of the FPN in their area, stakeholder engagement suggested that local authorities have tended to align with each other on the level of the FPN, meaning it does not differ significantly between areas.

Litter

The 2021/22 Welsh street cleanliness survey found that 95.5% of streets had an acceptable level of cleanliness (due to differences in methodology the Scotland-wide street cleanliness score cannot be directly compared). The “All-Wales Cleanliness Indicator” for 2021/22 was 69.8, which was a slight fall from the 70.1 recorded in 2018/19 but remains higher than the surveys undertaken between 2007/08 and 2017/18[118].

The minimum (and default) penalty for littering in Wales is £75 (Table 5), with the maximum being £150. As with flytipping enforcement in Wales, there is no obligation on an enforcing authority to offer an alleged offender the option of a fixed penalty for littering (over prosecuting offenders through the courts), and equally an alleged offender may choose not to accept or pay a fixed penalty, instead choosing to defend the case in court and risk a potentially higher penalty.

FPNs for littering can be issued by local authorities, community and town councils, National Parks Authorities and Police Community Support Officers (PCSOs), and persons accredited under community safety accreditation schemes. In Wales, like in England, private companies are often used for enforcement. This is not a model seen in Scotland. Stakeholder engagement suggested that this can be a useful tool when it comes to litter enforcement.

What does enforcement look like in other (non-UK) countries?

Enforcement is also used as a key tool in the battle against litter and flytipping around the world. To assess the models used elsewhere three countries of a similar socioeconomic demographic to Scotland were chosen, namely New Zealand, Sweden, and Spain.

All three countries, like Scotland, England and Wales use monetary penalties of various levels to enforce litter and flytipping (Table 6). In 2011 Sweden broadened enforcement powers to include a larger range of items. Despite this, litter and flytipping remains a significant issue. In New Zealand fines were increased in 2006 but there is little evidence to draw a link between increased fines and a reduction in instances. Spain has a relatively high maximum fine for minor offences, but there is little evidence to suggest whether this maximum is frequently applied.

Appendix 5 – Detailed overview of enforcement in other countries provides a more detailed overview of the enforcement models and wider issue of litter and flytipping in Sweden, Spain and New Zealand. As with Scotland it is challenging to fully understand the issues around litter and flytipping instances due to reporting and the challenges of collecting this data. It is also clear, even once consideration has been given to differing populations etc, that direct comparisons cannot be made between countries due to the varying ways in which littering and flytipping data is collected and reported on.

Table 6 Summary of penalties and fines used in New Zealand, Sweden and Spain

Country: Sweden

Overview of enforcement

800 Swedish Kronor (SEK) (approximately £63).

In 2022 Sweden issued 87 fines for littering[119]

A corporate fine can be issued for crimes related to business activities. This amounts to a minimum of SEK 5,000 (approx. £400) and a maximum of SEK 10 million (approx. £800,000)[120].

Country: New Zealand

Overview of enforcement

Any person or individual committing littering or illegally dumping waste is liable to an instant fine of $400 (approximately £204).

Maximum fines upon conviction can include:

Littering on public or private land – individual: fine not exceeding $5,000 (£2,600); corporate: fine not exceeding $20,000 (£10,500)

Littering on public or private land where it could endanger people – individual: imprisonment for no more than one month plus fine not exceeding $7,500 (£4,000) fine; corporate: fine not exceeding $30,000 (£15,000)

Country: Spain

Overview of enforcement

Minor offence: fine of up to 2,000 euros (£1,766)

Serious infraction: 2,001 euros (£1,766) to 100,000 euros (£88,000) (higher if hazardous)

Very serious infraction: 100,001 euros (£88,000) to 3,500,000 euros (£3 million) (higher if hazardous)

Contact

Email: nlfs@gov.scot

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback