Scottish Welfare Fund review: final report - data analysis appendix

An appendix to the main report of the review of the Scottish Welfare Fund, containing technical detail of the secondary analysis.

3. Factors shaping demand on the Fund

Key points

- Applications for Crisis Grants were already increasing pre-pandemic. As of June 2022, applications remained at a historically high level – they had not fallen back to pre-Covid levels of demand.

- Demand for Community Care Grants fell during the early stages of the pandemic (reflecting restrictions on house moves). However, demand subsequently rebounded and as of mid-2022 continued to exceed pre-pandemic levels.

- There are also seasonal factors in demand – with peaks either side of Christmas, and around school holiday periods

- Analysis indicates that levels of applications vary between local authorities, even after expected differences based on population size, children in low-income households, and benefit claimants are accounted for.

What are the key factors impacting on levels of demand for the SWF?

This section of the report considers the factors shaping the overall demand on the Fund. It considers overall application rates, before examining the local authority context, and how application rates compare with what we might expect, given the population size and socio-economic profile of areas. This section then looks at when demand/need is greater and applicants' main reasons for applying to the fund to help us understand the key drivers of demand and need.

Overall application rates

SWF data clearly shows that demand for Crisis Grants has increased and is continuing to increase. Applications for Crisis Grants had already increased substantially prior to the Covid-19 pandemic – there were 51,065 Crisis Grant applications April-June 2019, compared with 37,920 in the same period of 2016. Applications increased during the pandemic, particularly during the first lockdown period – there were 75,690 applications April-June 2020. However, as of June 2022, applications had not fallen back to their pre-Covid level – the Fund received 72,945 Crisis Grant applications April-June 2022.

Demand for Community Care Grants has also risen, albeit less sharply. Again, applications had started to increase pre-pandemic – there were 18,930 applications April-June 2019, up from 17,240 in the same period of 2016. In contrast with Crisis Grants, demand for Community Care Grants fell in the early months of lockdown in 2020, reflecting restrictions on house moves – April-June 2020 saw 15,795 applications. However, demand subsequently rebounded, and as of mid-2022 it continued to exceed pre-pandemic levels – there were 21,050 applications April-June 2022.

Source: SWF data to 30 June 2022 (Chart 1) Applications – 1 April 2013 to 31 June 2022

Application rates by local authority

The analysis below (Figure 2) compares application rates by local authority. In order to allow for the different size and levels of expected financial hardship in different areas, the number of applications is compared with the population, the total number of children in low-income households and the total number of Universal Credit claimants. This is compared with analysis of the SIMD 2020 income domain used in the allocation of SWF funding[13].

These indicators are chosen to allow the 'standardisation' of results to remove the impact of larger, urban authorities. Comparing the number of applicants provides a basic 'per capita' standard rate, while rates per low income household and per Universal Credit Claimant allows us to standardise to take account of levels of income poverty. This allows us to compare local authorities with lower and higher levels of poverty, to assess whether some local authorities have higher or lower than expected rates of applications to the Fund, given the overall level of need in their area. The number of children in low income household and the number of Universal Credit Claimants is chosen as these are indicators that are updated regularly and are reasonable proxies for the level of poverty and benefit dependency in an area.

First, the application rate is compared to the population[14]in each local authority. That is the rate of application per 1,000 people.

Source: SWF Annual Report 2020/21; NRS Population mid-year estimates 2020

Across Scotland, the average application rate in 2019/2020 was 54.9 applications per 1,000 people. There were significantly higher application rates (at least 1 standard deviation above the mean) in West Dunbartonshire (94.9) Clackmannanshire (87.2) Fife (86.5) Glasgow City (83.9) and North Ayrshire (83.5). Significantly lower than average application rates were found in the Orkney Islands (6.7), East Renfrewshire (11.0), Eilean Siar (11.3), the Shetland Islands, Highland (25.4) and East Dunbartonshire (25.5).

A similar pattern was observed in 2020/21 (average up to 65.1), except that Aberdeen replaced North Ayrshire as among the areas with the highest application rates per 1,000 and East Dunbartonshire became within one standard deviation of the mean (average) rate.

For Community Care Grant applications, the average application rate was 14.3 applicants per 1,000 in 2019/20 and rose to 15.4 per 1,000 in 2020/21. Significantly higher than average application rates were seen in West Dunbartonshire (27.6) Glasgow (27.0) Clackmannanshire (23.0) North Ayrshire (21.2) Dundee (20.7), Inverclyde (19.9) and East Ayrshire (19.4). At the other end of the scale, below average rates of application for Community Care Grants (between 3.6 and 6.5 per 1,000) were found in the Orkney Islands, Eilean Siar, East Renfrewshire, the Shetland Islands and East Dunbartonshire.

There was a similar pattern in which areas had higher and lower application rates for Crisis Grants, though Inverclyde was closer to average rather than above average as for CCGs and Argyll and Bute was among the local authorities with lower than average applications.

Source: SWF Annual Report 2020/21; NRS Population mid-year estimates 2020

Source: SWF Annual Report 2020/21; NRS Population mid-year estimates 2020

To explore how these higher and lower than average applicant rates relate to underlying levels of need, the rate of applications was compared with two proxy measures – the number of applications as a proportion of the number of children in low-income households and as a proportion of Universal Credit claimants. These are used as widely accepted reasonable proxies of child poverty and overall benefit dependency.

The number of children in low-income households and the number of UC claimants are two measures of financial vulnerability. So, if we divide the total number of applicants by the number of children in low-income households or by the UC claimant count, we are controlling for the overall level of need to some extent. Where applicant rates differ despite controlling for need, there may be other factors at work.

Across Scotland, the average number of SWF applications per child in a low-income household was 1.8 in 2019/20 and 2.9 in 2020/21. The local authorities with a higher than average rate of SWF applications per child in a low income household in 2019/20 were – Aberdeen (3.2) West Dunbartonshire (2.5) Fife (2.4) and Clackmannanshire (2.2). Lower than average application rates compared with numbers of children in low-income households were found in the Orkney Islands, East Renfrewshire, Eilean Siar, the Shetland Islands and Highland. A similar pattern is observed for 2020/21 although Edinburgh replaced Clackmannanshire in the higher than average applicant group (although this may be related to data issues relating to Edinburgh highlighted earlier).

StatXplore: DWP data 2019/20 and 2020/21. UK statistics on children in low income households; SWF Annual Report 2020/21

Note to Figure: Figures 'per child in low-income households' show the number of applications divided by the total number of children defined as in a household with an absolute low income. Absolute low-income is defined as a family whose equivalised income is below 60 per cent of the 2010/11 median income adjusted for inflation. Localised estimates are based on administrative data such as the number of children in out-of-work benefit households (DWP) and children in low-income families derived primarily from Tax Credits income data (HMRC). Estimates are aligned to Household Below Average Income regional estimates. NB - data collection for FYE 2021 was affected by the coronavirus (Covid-19) pandemic. Figures for FYE 2021 are subject to additional uncertainty and may not be strictly comparable with previous years.

This means that, even controlling for the level of need (as proxied by the number of children in low-income households) some local authorities have higher than average and lower than average levels of SWF applications.

For Crisis Grants, the average application rate per low-income child was 1.4 in 2019/20 and 2.4 in 2020/21. Higher than average applications per low-income child were found in 2019/20 in Aberdeen, Fife, West Dunbartonshire and Renfrewshire. The lowest rates were in the Orkney Islands, East Renfrewshire, Eilean Siar, the Shetland Islands and Highland. The same pattern was observed in 2020/21, except that Edinburgh replaced Renfrewshire in the higher than average applications group. Again, this may relate to Edinburgh's noted data issues.

StatXplore: DWP data 2019/20 and 2020/21. UK statistics on children in low income households; SWF Annual Report 2020/21

Looking at Community Care Grants shows similar results, with some changes at the top and bottom. Application rates are an average of 0.4 per child in a low-income household in 2019/20 (0.5 in 2020/21) with higher than average rates in West Dunbartonshire, Inverclyde, Glasgow City, Aberdeen, Dundee and Clackmannanshire. Lower than average Community Care Grant application rates per low-income child were found in the Orkney Islands, Eilean Siar, East Renfrewshire, Moray, the Scottish Borders and the Shetland Islands. A similar pattern is observed in 2020/21, although Glasgow and Clackmannanshire were replaced by Edinburgh in the group with higher than average applications.

StatXplore: DWP data 2019/20 and 2020/21; UK statistics on children in low income households; SWF Annual Report 2020/21

Another needs-based indicator used to compare the application rates was the claimant count for Universal Credit (UC). Like children in low-income households, we would expect that we would find greater risk of financial hardship in areas with higher numbers of UC claimants so creating an applicant rate per UC claimant controls for this to some extent. The average number of SWF applications per UC claimant was 1.6 in 2019/20 and 0.9 in 2020/21 (with the drop largely driven by the significant increase in the claimant count).

Using Universal Credit, we see a similar pattern of higher and lower than average applications, with significantly higher than average applications per UC claimant in Aberdeen, West Dunbartonshire, Edinburgh and Glasgow and significantly lower than average applications per UC claimant in the Orkney Islands, Highland, Eilean Siar, East Renfrewshire and the Shetland Islands. A similar pattern is observed in 2020/21 but Dumfries and Galloway, Fife and West Lothian are higher than average and Glasgow is closer to the average.

Source: StatXplore August 2020 and August 2021 UC Claimant Count; SWF Annual Report 2020/21

Community Care Grant applications per UC claimant were 0.4 in 2019/20 and 0.2 in 2020/21 (again, down due to the increased claimant count). Significantly higher than average applications per claimant were found in West Dunbartonshire, Glasgow, Aberdeen and Edinburgh and significantly lower than average applications per UC claimant were found in Eilean Siar, Highland and the Orkney Islands. A similar pattern was found in 2020/21 although Dumfries and Galloway replaced Aberdeen in the higher than average applications group and the Shetland Islands and South Ayrshire replaced the Orkney Islands as among the lowest applications per UC claimant.

Source: StatXplore August 2020 and August 2021 UC Claimant Count; SWF Annual Report 2020/21

Source: StatXplore August 2020 and August 2021 UC Claimant Count; SWF Annual Report 2020/21

Across Scotland, the average rate of Crisis Grant application was 1.2 applications per UC claimant in 2019/20 and 0.7 in 2020/21. Significantly higher application rates were found in Aberdeen, Edinburgh, West Dunbartonshire, Fife and Renfrewshire. The same pattern was observed in 2020/21 except West Lothian replaced Renfrewshire. Much lower Crisis Grant application rates per UC claimant were found in the Shetland Islands, South Lanarkshire, Eilean Siar, East Renfrewshire, Highland and the Orkney Islands.

This analysis shows that there are areas that get a higher than expected number of applications even controlling for proxies of need. Higher than expected rates of application are evidenced in – Aberdeen, West Dunbartonshire, Fife, Clackmannanshire, Edinburgh, Glasgow and Renfrewshire, as well as Inverclyde and Dundee. Lower than expected rates of application were seen in the Orkney Islands, East Renfrewshire, Eilean Siar, the Shetland Islands and Highland, Moray and the Scottish Borders. In other words, rural areas commonly see lower than expected application rates while the large urban centres see higher than expected application rates.

Drawing together findings on the proportion of SWF applicants by local authority, compared with the proportion of UC claimants and children in low-income households, we can more easily see where locations have a lower or higher than average proportion of applications.

Source: StatXplore August 2020 UC Claimant Count; SWF Annual Report 2019/20 and UK statistics on children in low income householders

The local authorities that stand out as having a higher than might be expected share of all the SWF applications are Glasgow – with 17.8% of all SWF applications (2019/20) compared with 16.4% of children in low-income households (2019/20) and 12.8% of UC claimants (August 2020). Fife also had 10.8% of SWF applications compared with 8.7% of UC claimants and 7.9% of children in low-income households. Edinburgh, Aberdeen and West Dunbartonshire also have a higher than might be expected proportion of SWF applicants compared with their share of UC claimants and children in low-income households.

The most notable local authorities with a lower than might be expected proportion of applications included South Lanarkshire with 4% of applicants but 7.1% of UC claimants and 5.8% of children in low-income households and Highland with 2% of SWF applications compared with 4.5% of UC claimants and 4% of children in low-income households. This pattern is observed for other rural authorities – the Scottish Borders, Moray, East Dunbartonshire, Argyll and Bute, East Renfrewshire and the Island authorities. Although these may seem small proportional differences, the variations amount to a significant potential increase in applications if these were more in proportion to the number of UC claimants. Across the 8 local authorities with the lowest application rates, if these increased to the rate of UC claimants, they would collectively receive 6.7% of applications rather than 4.5% - up from 13,515 applications to 19,979 applications.

SIMD and applications

The original funding assumptions for the SWF budgets were based on analysis of SIMD, with around £50 allocated per income deprived person[15], based on the income domain of the SIMD 2020 (see Table 1 below). This was not the expected rate of award but a means of allocating the overall budget to areas according to the level of need.

Analysis of applications per income deprived person from SIMD 2020 show whether or not areas have a higher or lower than expected rate of applications given their poverty profile (in other words, whether their applications per income deprived person are above or below the overall Scottish average number of applications per income deprived person). This highlights similar findings to that above on Universal Credit claimant count and children in low income households –

- Aberdeen had a higher than might be expected overall rate of applications for Community Care Grant and Crisis Grants in 2019/20 and 2020/21, given the number of income deprived households recorded on SIMD, so is higher than the Scottish average rate.

- Clackmannanshire had a higher than average/might be expected overall rate of applications and for Community Care Grant and Crisis Grants in 2019/20 but not in 2020/21.

- Fife had a higher than expected overall rate of applications for Crisis Grants in 2019/20 and 2020/21.

- Edinburgh had a higher than expected overall rate of applications and for Community Care Grant and Crisis Grants in 2020/21 but not in 2019/20. In the case of Crisis Grants, this may be partly due to data issues as highlighted above, though.

- West Dunbartonshire and West Lothian also had higher than expected application rates in 2020/21 overall and for Crisis Grants. West Dunbartonshire also had higher than expected applications for Community Care Grants in both years.

- Glasgow had a higher than expected rate of applications for Community Care Grants in 2019/20, and Stirling and East Lothian did in 2020/21. Even allowing for data issues in Glasgow in March 2020 this is still higher than would be expected.

- East Renfrewshire, Eilean Siar, the Orkney Islands and Shetland Islands had a lower than expected rate of applications compared with the number of income deprived households. Highland had a lower than expected rate of applications overall and Crisis Grant applications in 2019/20 and Argyll and Bute had a lower than expected rate of Crisis Grant applications in 2020/21.

So, overall, large urban centres have higher than expected application rates, and rural areas lower than expected, given the area profile in terms of poverty, based on all the measures looked at, but there are exceptions to this and other types of areas that have high/low application rates, so demand is not only shaped by the urban-rural experience.

Expenditure differs, also, with average spending in Clackmannanshire and Glasgow of over £70 per income deprived person in 2019/20, and £68 in Fife (against the budget of around £50 per income deprived person) but just £47 per income deprived person in Aberdeen. This is based on the actual spending compared with the SIMD allocation assumptions underpinning funding. So higher application rates do not always lead to higher expenditure (more on this later, alongside more on actual expenditure/average awards per recipient).

| LA | Allocation per income deprived person (2019/20) | Spent 2019/20 per income deprived person | SWF apps 2019/20 per income deprived person | SWF apps 2020/21 per income deprived person | CCG apps 2019/20 per income deprived person | CCG apps 2020/21 per income deprived person | CG apps 2019/20 per income deprived person | CG apps 2020/21 per income deprived person |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scotland | £50 | £57 | 0.46 | 0.54 | 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.34 | 0.41 |

| Aberdeen City | £46 | £47 | 0.85 | 1.03 | 0.16 | 0.17 | 0.69 | 0.86 |

| Aberdeenshire | £45 | £47 | 0.46 | 0.49 | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.35 | 0.37 |

| Angus | £49 | £49 | 0.42 | 0.41 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.31 | 0.30 |

| Argyll and Bute | £52 | £51 | 0.27 | 0.29 | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.18 | 0.18 |

| Clackmannanshire | £50 | £70 | 0.61 | 0.62 | 0.16 | 0.15 | 0.45 | 0.47 |

| Dumfries and Galloway | £51 | £63 | 0.54 | 0.63 | 0.14 | 0.15 | 0.40 | 0.48 |

| Dundee City | £50 | £57 | 0.37 | 0.49 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.24 | 0.35 |

| East Ayrshire | £51 | £51 | 0.44 | 0.47 | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.32 | 0.32 |

| East Dunbartonshire | £49 | £49 | 0.36 | 0.52 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.27 | 0.41 |

| East Lothian | £47 | £48 | 0.50 | 0.53 | 0.13 | 0.16 | 0.37 | 0.37 |

| East Renfrewshire | £52 | £52 | 0.17 | 0.19 | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.10 | 0.11 |

| City of Edinburgh | £52 | £58 | 0.46 | 0.91 | 0.11 | 0.17 | 0.35 | 0.73 |

| Eilean Siar | £54 | £35 | 0.11 | 0.15 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.08 | 0.11 |

| Falkirk | £51 | £40 | 0.40 | 0.39 | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.29 | 0.28 |

| Fife | £51 | £68 | 0.73 | 0.81 | 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.61 | 0.68 |

| Glasgow City | £51 | £71 | 0.45 | 0.50 | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.30 | 0.37 |

| Highland | £48 | £41 | 0.26 | 0.28 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.17 | 0.19 |

| Inverclyde | £48 | £52 | 0.35 | 0.35 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.24 | 0.24 |

| Midlothian | £50 | £50 | 0.57 | 0.65 | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.46 | 0.53 |

| Moray | £48 | £49 | 0.39 | 0.38 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.31 | 0.29 |

| North Ayrshire | £51 | £54 | 0.49 | 0.39 | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.36 | 0.29 |

| LA | Allocation per income deprived person (2019/20) | Spent 2019/20 per income deprived person | SWF apps 2019/20 per income deprived person | SWF apps 2020/21 per income deprived person | CCG apps 2019/20 per income deprived person | CCG apps 2020/21 per income deprived person | CG apps 2019/20 per income deprived person | CG apps 2020/21 per income deprived person |

| North Lanarkshire | £51 | £52 | 0.42 | 0.40 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.34 | 0.31 |

| Orkney Islands | £49 | £42 | 0.10 | 0.16 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.08 |

| Perth and Kinross | £51 | £60 | 0.50 | 0.64 | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.38 | 0.51 |

| Renfrewshire | £51 | £55 | 0.49 | 0.56 | 0.10 | 0.13 | 0.39 | 0.43 |

| Scottish Borders | £51 | £52 | 0.31 | 0.30 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.23 | 0.22 |

| Shetland Islands | £51 | £66 | 0.26 | 0.15 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.18 | 0.08 |

| South Ayrshire | £52 | £51 | 0.35 | 0.40 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.27 | 0.31 |

| South Lanarkshire | £51 | £63 | 0.30 | 0.39 | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.16 | 0.25 |

| Stirling | £51 | £58 | 0.57 | 0.65 | 0.14 | 0.17 | 0.43 | 0.47 |

| West Dunbartonshire | £51 | £53 | 0.53 | 0.78 | 0.15 | 0.21 | 0.38 | 0.58 |

| West Lothian | £51 | £58 | 0.55 | 0.75 | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.41 | 0.61 |

When do people apply to the SWF?

Applications by month

In April 2013 there were just over 11,000 applications to the Scottish Welfare Fund, increasing to almost 32,000 by March 2022 (an increase of 185%). Over this period, Community Care Grant applications increased from around 3,750 per month to around 6,800 (an 81% increase) while Crisis Grants applications increased from 7,350 to around 25,200 (a 238% increase).

In the first few years of the Fund, there seemed to be peaks in Spring and Autumn each year while in later years there appear to be more peaks – at around January and August, with a smaller peak in October and November, though applications have been consistently lower in December each year.

Source: Chart 1: Applications to the Scottish Welfare Fund - Scotland – Monthly (1 April 2013 to 31 March 2022)

This pattern suggests that the fund is responding to periods of greater need – such as the winter months either side of Christmas, when debts might be higher alongside higher heating costs, as well as around school holiday periods when expenditure may be suddenly higher.

Variation by local authority

Looking across all the years of data from 2013/14 to 2020/21 (to allow analysis by month in the smaller local authorities), we see common periods with higher than average applications.

For Community Care Grants -

- October and November, alongside February and March are the months where there are most commonly a higher than average number of Community Care Grant applications, with below average numbers of applications in December in the majority of local authorities.

- 3 local authorities see a higher than average number of applications in January, 6 in February, 19 in March, 14 in October and 15 in November. This may be associated with the winter and additional fuel costs impacting on the ability to afford other items.

- Other peaks include August in Argyll and Bute, Orkney and West Dunbartonshire and September in Clackmannanshire, Highland and the Scottish Borders.

For Crisis Grants –

- All 32 local authorities had a higher than average number of applications in January, while 20 of 32 had lower than average applications in December. Only the Shetland Islands had a higher than average number of applications in December. The post-Christmas period is clearly a period of financial pressure.

- 30 of 32 local authorities had higher than average applications during March (with the exception of East Renfrewshire and the Orkney Islands). 15 of 32 also had lower than average applications in April. This may indicate that applicants are encouraged to apply or perceive the end of the financial year as a period when local authorities may be more generous in spending.

- Other periods of higher than average applications include August in South Lanarkshire and November in the Orkney Islands and East Renfrewshire and February in Stirling and the Scottish Borders.

Why do people apply to the SWF?

Main reasons for applying

The data analysis has been used to examine what patterns and trends are evident in relation to the level of and reasons for applications to the Fund – and what these might tell us about both demand and, potentially, underlying need. This considers trends both pre- and post the severe phases of the Covid-19 pandemic and restrictions.

Number and share of applications

The number of applications to the Fund has increased significantly since 2013/14, from 58,020 to 87,900 Community Care Grants (a 51% increase) and from 114,520 to 268,265 Crisis Grants (a 134% increase). At the same time, Crisis Grant applications have also increased as a share of total applications – Crisis Grants were 66% of all SWF applications in 2013/14 and increased to 75% of the total by 2021/22.

Source: SWF Annual Report 2021/22, Tables 4 and 6

Looking at variation by local authority, we have used 2019/20 data as the latest pre-pandemic data. This is intended to compare the 'non-pandemic-related crisis' or 'pre-pandemic-related crisis' experiences by local authority as noted in Chapter 1.

Source: SWF Annual Report 2020/21, Tables 4 and 6

Across Scotland in 2019/20, 74% of applications to the SWF were for Crisis Grants and 26% were for Community Care Grants. The proportion of Crisis Grants was significantly higher than average (at least 1 standard deviation above the mean or more than 80% of applications) in Fife, Midlothian, Aberdeen, Renfrewshire and North Lanarkshire. Crisis Grants were a far smaller proportion of applications (at least 1 standard deviation below the mean, 71% or less) in East Ayrshire, West Dunbartonshire, Inverclyde, Eilean Siar, Glasgow, the Shetland Islands, Highland, Dundee, Argyll and Bute, East Renfrewshire, South Lanarkshire and Orkney.

In contrast with overall levels of applications vs expected levels, having a lower than average proportion of Crisis Grant applications compared with Community Care Grant applications is not a more rural phenomenon, with some large urban authorities also having a more mixed profile of applications.

Reasons for applying

The charts below show trends over time in the reasons for applying for a Community Care Grant and a Crisis Grant. The most significant change over time for Community Care Grant applications has been the increase in the proportion that are due to 'families facing exceptional pressure', which has increased from 14% to 35% of reasons. This has occurred alongside an increase in and then reduction in the prevalence of 'helping people to stay in the community' as a reason, which increased from 31% to 45% of applications before falling back to 29%. 'Planned resettlement after an unsettled way of life' has gone up and down, starting at around 5% in 2013 to reach almost 15% by 2017, before falling back to 10% of reasons for application. 'Moving out of institutional accommodation' accounted for about 10% of applications initially, increasing to 15% in early 2014 before reducing to 4% by 2022.

Source: SWF Annual Report 2022, Chart 2: Reasons for Application - Community Care Grants – Quarterly, 1 April 2013 to 31 March 2022 (See Annex 1 for full list of reasons)

More recently, between April and June 2020 'planned re-settlement after an unsettled period' dropped to just 4% of reasons from 10% the previous quarter, recovering back to 10% by January to March 2022. This is likely to be due to a reduction in homeless applications over the pandemic period. Emergency Covid legislation protected most tenants in the private and social rented sectors with measures requiring landlords, in most cases, to give extended notice of their intention to seek possession before starting court action[16].

From January to March 2020 onwards, the number of applications to help people stay in the community fell, from 36% of reasons to 29% by March 2022.

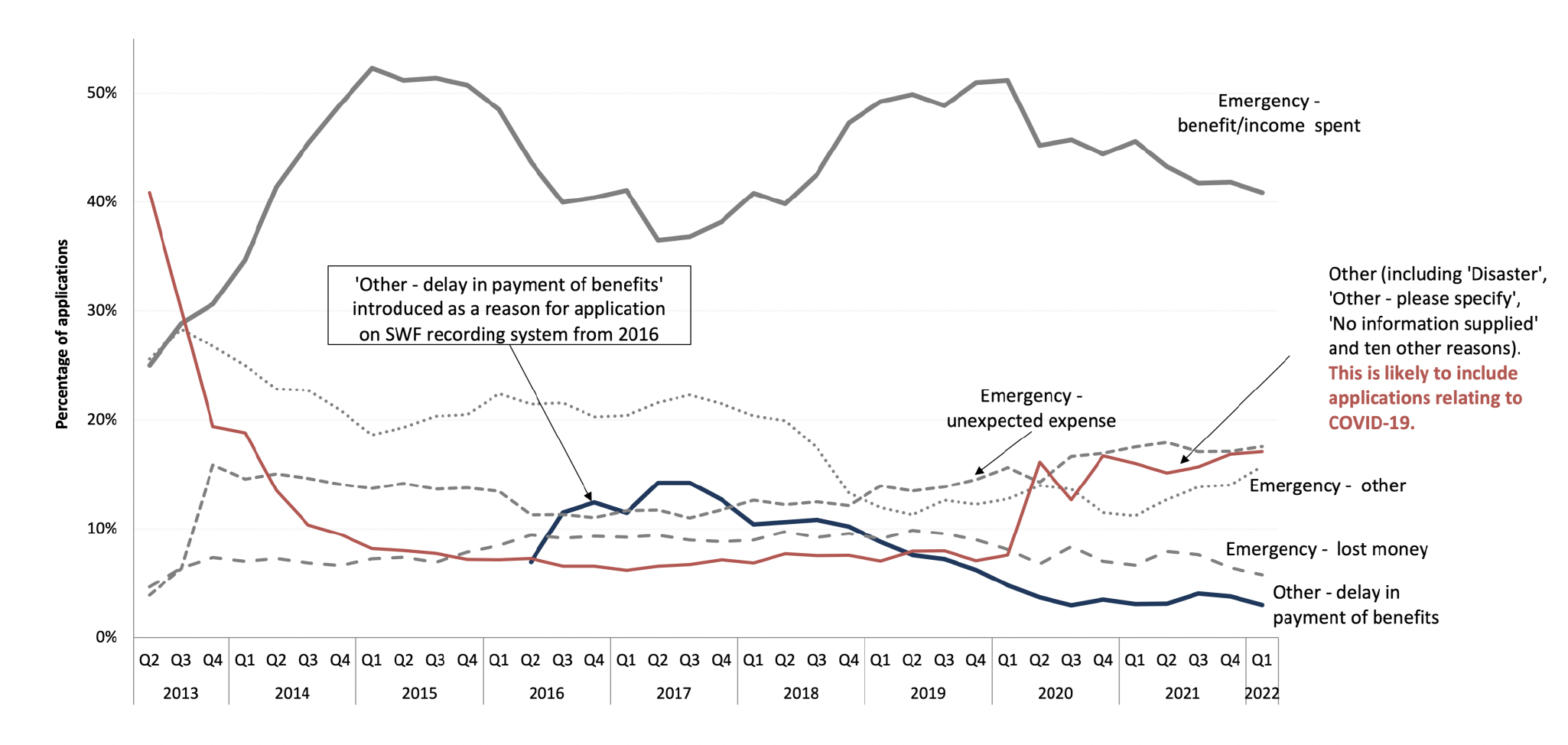

Source: SWF Annual Report 2022, Chart 3: Reasons for Application – Crisis Grant – Quarterly, 1 April 2013 to 31 March 2022. (See Annex 1 for full list of reasons)

For Crisis Grants, benefit/income being spent accounted for 25% of reasons for applying in Quarter 1 of 2013/2014 and peaked at around half of all application reasons in early 2015. It then fell back to around 35% in 2017 before increasing again to 50% by early 2020, falling back again to 41% more recently. Delays in benefit payments were included from 2016 when this accounted for around 10% of reasons, before peaking at around 15% of reasons in 2017 and reducing in frequency more recently to around three to four per cent. The increased use of the delays in benefits reason corresponded with a reduced use of benefit/income being spent, with more recent prevalence in money being spent than benefit delays.

The Covid pandemic period (from March 2020 onwards) was associated with a reduction in the proportion of applications attributed to 'benefit/income being spent', down from 51% in Jan-March 2020 to 41% in the same period in 2022, while 'other reasons' increased from 8% to 17% over the same period. This is likely to be caused by the fact that, during the pandemic, Universal Credit was uplifted by £20 per week, so people were less likely to run out of benefit income, while the cover for self-employed people was more patchy[17], compared with furloughed employees, and some sudden redundancies occurred[18].

'Other emergencies' and cases where the reason for applying was 'uncoded/other specify' have both reduced in frequency, while 'lost money' has remained fairly stable. There was increased use of the 'other specify' code from the first quarter of 2020, when the pandemic lockdown started.

Taken together, these findings show that the reasons people apply to the Scottish Welfare Fund has changed over time, with more families in pressure applying and more people running out of money. The relationship between this and the changing characteristics of applicants is explored further later.

Variation in reasons by local authority

There were significant variations between local authorities in the patterns of reasons for applying for a Community Care Grant (in the latest quarter before the Covid lockdown). For example, 'helping people stay in the community' accounted for over 80% of reasons in North Ayrshire and Dundee and over 60% of reasons in Edinburgh and Dumfries and Galloway, compared with fewer than 10% of reasons in Fife, West Lothian, South Lanarkshire, East Renfrewshire, North Lanarkshire and Falkirk (compared with 35% of reasons across Scotland).

Source: Table 9: Reason for applying for a Community Care Grant by Local Authority, For quarter: 1 January to 31 March 2020

As with other local authority comparisons in this report, it is important to apply caution in interpretation - differences in reasons could reflect both differences in coding or recording practices or differences in underlying needs between areas (or a combination of the two). However, they are useful as an indicator of the overall degree of variability in reported reasons.

Looking across the whole of the 2019/20 data shows similar results, with 'helping people stay in the community' used more often in North Ayrshire (81% of applications), Dundee (80%) Midlothian (70%) Edinburgh (64%) and Dumfries and Galloway (59%) compared with 36% of all applications across Scotland. This is mainly driven by the number of reasons relating to 'Help with expenses for improving a home to maintain living conditions' (a sub-set of the overall category of helping people to stay in the community).

Source: Table 9: Reason for applying for a Community Care Grant by Local Authority, For quarter: 1 January to 31 March 2020

There was also significant variation between the proportion of reasons for Community Care Grant applications relating to 'families under exceptional pressure' – from over 60% of reasons in South Lanarkshire, East Renfrewshire, East Lothian, Highland and Perth and Kinross, to 11% or fewer in North Ayrshire, Edinburgh, Dundee, Midlothian and Eilean Siar (compared with the average across Scotland of 33%).

Again, across the whole of the pre-pandemic 2019/20 data we see a similar profile, with 'families under exceptional pressure' more commonly the reason for applying in Perth and Kinross (79% of applications) Highland (72%) East Renfrewshire (73%) East Lothian (68%) and South Lanarkshire (62%).

Changing CCG application rates and disability

It was suggested in the evidence review that fewer applications to help people to stay in the community indicated a reduction in the use of the fund among people with a disability. Comparing the reasons given by applicants with someone in the household with a long-term illness or disability, 34% of those reporting an illness or disability compared with 33% of applicants who did not report a disability applied to help them stay in the community. Likewise, 39% of households with an ill or disabled person in the household applied due to being a 'family under exceptional pressure', as did 37% of those without an illness/disability. So the trend towards 'exceptional pressure' reasons is not necessarily an indicator of fewer people with disabilities applying. Families with children also commonly gave this reason – 48% of single parents and 48% of couples with children were under exceptional pressure, compared with 35% of all Community Care Grant applicants.

The median age of applicants to the SWF has been 34 years since the scheme began, so applicants are not getting younger, on average. In 2013-14, 29% of applicants said someone in the household with a physical or mental health condition or illness lasting or expected to last 12 months or more, increasing to between 30%-31% in the intervening years, with 33% of applicants in 2019/20 and 32% of applicants in 2020/21. The true proportion of applicants with a disabled person in the household is likely to be somewhat higher, as around 30% of applicants do not disclose this information.

Based on the applicants who provide information on long-term illness/disabilities, there is no evidence that applications from disabled people have been reducing over time. Changes in the profile of applicants over time is explored further below in the analysis of applicant characteristics, particularly vulnerability.

Analysis of SWF data, prison data and homelessness data provided by the Scottish Prison Service (based on analysis of Scottish Government data) suggests that only 16% of people leaving prison during 2019/20 applied to the SWF while 25% were recorded as homeless on leaving. In some LAs, no people leaving prison were recorded as having applied to the SWF while in others up to 10 times as many SWF applications had been received from people leaving prison as had applied as homeless with their previous accommodation as prison. One LA had 225 homeless applicants reporting prison as their previous accommodation but only 20 applicants for Community Care Grants from prison leavers. These findings indicate there are likely to be inconsistencies in the recording of people leaving prison in the CCG data.

Crisis Grant reasons

There was less variation in the reasons for applying for a Crisis Grant by local authority, with most applying for emergency reasons. Around 50% of reasons for Crisis Grant applications in 2019/20 (pre-pandemic) were emergencies due to benefit/income being spent. This was particularly high in some local authorities – 84% in Eilean Siar, 80% in Dumfries and Galloway, 80% in North Ayrshire, 78% in Highland and 77% in Perth and Kinross. In Argyll and Bute, 89% of crisis grant applications were due to an unexpected expense, also 63% in Glasgow (compared with 14% overall). Benefit delays accounted for 6% of all applications but 25% in the Orkney Islands, 20% in South Ayrshire,18% in Aberdeen and 16% in Glasgow.

Source: Table 12: Reason for applying for a Crisis Grant by Local Authority, For quarter: 1 January to 31 March 2020

Underneath these overall reasons for applying for Crisis Grants, there were some variations across the whole of 2019/20 –

- Almost 30% of applicants recorded as stranded away from home and 17% with benefit delays applied in Aberdeen (Aberdeen had 6% of all Crisis Grant applications)

- Almost a third recorded as having had an 'other disaster' applied in Angus (where 2% of applicants were) while a quarter were in Edinburgh (7%) and a quarter were in East Ayrshire (3% of all applications.

- Glasgow had 71% of all applications for an unexpected expense, 36% of applications due to fires, 47% of floods and 23% of explosions as well as 41% of applications due to benefit delays (compared with 16% of all applications)

- 32% of those in danger of rough sleeping were in West Lothian (just 4% of all Crisis Grant applicants) and 21% in Glasgow.

- 'Other' emergencies were disproportionately found in West Dunbartonshire (20% of these applicants) Edinburgh (16%) and North Lanarkshire (10%).

These differences might indicate different local risk profiles for different types of emergency and/or might indicate differences in recording or coding practices between areas, with some areas more likely to use some codes over others. However, as almost two-thirds of local authorities gave 'benefit/income spent' as the reason for 70% or more of their applications, these other codes were less commonly used.

The local authorities with a far lower proportion of applications recorded as benefit/income spent in 2019/2-20 were South Lanarkshire (17%) Clackmannanshire (12%) and Argyll and Bute (0.2%). Argyll and Bute recorded 89% of applications as an 'unexpected expense' while South Lanarkshire and Clackmannanshire more commonly recorded 'other emergencies' and 'other' reasons for applying. Again, this seems to indicate different recording/coding practices.

Ease of application

Being able to easily apply to the Fund – through having support and through multiple channels – is also related to the factors underlying demand for the fund. Are applicant rates lower among the types of groups that tend to use support and face-to-face options, for example? This is explored in more detail under 'Experiences and Outcomes'.

Contact

Email: Socialresearch@gov.scot

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback