Sandeel fishing consultation: strategic environmental assessment - draft environmental report

The draft environmental report produced from the strategic environmental assessment on proposals to close fishing for sandeel in all Scottish waters.

5. Results of SEA

5.1 Overview

5.1.1 The purpose of this section is to report the results of the SEA.

5.1.2 It is considered that the extension of the sandeel closure to all Scottish waters has the potential to lead to significant beneficial environmental effects.

5.1.3 An overview of the implications of the extended closure on the environment, namely the Biodiversity, Flora and Fauna headline topic and component topics, and the Water quality, Resources, and Ecological Status headline topic and component topics (see Section 3.3) and SEA objectives, is provided in this section. Further detail and supporting evidence can be found in the paper 'Review of Scientific Evidence on the Potential Effects of Sandeel Fisheries Management on the Marine Environment' which supports this consultation.

5.2 Environmental effects

Potential effects on seabirds

5.2.1 A large proportion of seabird species in Scotland include sandeel in their diet during the breeding season.

5.2.2 A consistent pattern in the way seabird breeding success changes with forage fish abundance has been reported for many seabird-forage fish interactions around the globe. Known as 'one-third for birds', seabird breeding success has been shown to vary little or not at all at intermediate and high forage fish abundance, but once forage fish abundance dropped below a threshold of one-third of maximum biomass, seabird breeding success rapidly declined.[135] This relationship has also been found for seabirds feeding on sandeel, e.g., for breeding success of Arctic skua, great skua and black-legged kittiwake on Foula in relation to the Shetland sandeel total stock biomass.[136][137] A similar relationship has also been found for a proxy of adult survival at the Isle of May for kittiwakes.[137]

5.2.3 Seabird breeding success is influenced not only by sandeel biomass, abundance, and quality but also by their availability. Assessing sandeel availability to seabirds, especially surface feeders, is difficult as availability varies as sandeel move between the water column and the sediment, and their depth within the water column. Temporal availability of sandeel also influences seabird breeding success. The peak in sandeel abundance, and sandeel of the appropriate age and size, needs to coincide with the seabird breeding season. Breeding success of three seabird species on the Isle of May was greatest when the sandeel fishery Catch Per Unit Effort (CPUE in June was high and the May/June CPUE ratio (an index of the timing of the onset of sandeel burying behaviour) was low, implying a peak abundance in May is too early to benefit seabird chicks.[138]

5.2.4 The extent to which seabirds can dive down into the water column to obtain sandeel at different depths varies greatly among species. Surface feeding seabirds, such as terns and black-legged kittiwake, can only take fish very close to the surface whereas other species such as common guillemot, razorbill and Atlantic puffin can dive to considerable depths. Guillemot and European shag can also extract fish from the sediment on the seafloor and so can feed on sandeel even when they are not in the water column.

5.2.5 The extent to which seabirds are dependent on sandeel varies among species. For example, guillemot species have been shown to have greater capability to switch to foraging on sprat and small herring when sandeel are unavailable compared to black-legged kittiwake.[138] During breeding many Scottish seabird populations exploit seasonal peaks in sandeel abundance, feeding on both adult (1+ year group) and juvenile (young-of-the-year; age 0) age classes.[139][140]

5.2.6 When the Shetland sandeel stock collapsed in the 1990s, many seabird species exhibited reduced breeding success[141][142][143][144] and survival.[141][142][145][146] The extent to which sandeel populations drive patterns in kittiwake breeding success among colonies appears to be stronger in Shetland and Orkney than further south, due to the absence of alternative prey.[147]

5.2.7 Due to the challenges of studying seabird diet in the non-breeding season, when birds are at sea and away from their colonies, less is known about the importance of sandeel in seabird diet during this period.[148] Despite this, the limited information that exists suggests that seabirds forage on a wider variety of prey during the non-breeding season, but still include sandeel to some extent.[149][150]

5.2.8 While sandeel have traditionally been considered one of the most abundant and energy rich prey for seabirds in Scotland[151][152][153] the availability, size and calorific content of this species has declined in recent decades.[154][155][156][157] As a result, many seabird populations now appear to have a reduced dependency on sandeel, although this can be highly variable among years and colonies.[158][159][160][161][162][163]

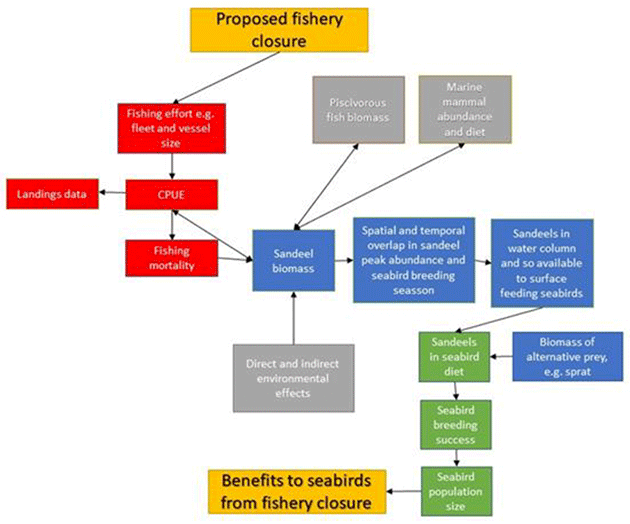

5.2.8 Obtaining measures of how a sandeel fishery changes the abundance or availability of sandeel to seabirds, and hence seabird demography, is not straightforward. Figure 33 illustrates the multiple complexity of linking changes to a sandeel fishery to seabird population size.

5.2.9 On two separate occasions, industrial sandeel fisheries have been closed due to concerns about their impacts on the breeding success of seabirds.[162] During the mid to late 1990s, a small sandeel fishery off Shetland was closed following declines in breeding success of seabirds including Arctic tern,[164] great skua[165] and black-legged kittiwake.[166] More recently, an industrial sandeel fishery on the Wee Bankie, Scalp Bank and Marr Bank that opened in 1990 was closed in 2000 due to concerns about the fishery impacting breeding success of seabirds nesting around the Firth of Forth, including guillemot species, razorbill, black-legged kittiwake and, to some extent Atlantic puffin, were known to use the fished area for foraging during the breeding season.[167]

5.2.10 The evidence for the fishery reducing breeding success, particularly for kittiwake, was so strong that ICES recommended using 'the criterion of kittiwake breeding success falling below 0.5 fledged chicks per well-built nest for three successive seasons as the threshold to close sandeel fisheries in areas important for foraging by the kittiwake colonies being monitored'.[168]

5.2.11 Following closure of the Wee Bankie sandeel fishery in 2000, sandeel abundance initially increased, as did black-legged kittiwake breeding success. Consumption rates of age 0 sandeel were higher after the fishery closure, despite the fishery not targeting age 0 sandeel.[169] However, no significant relationship between sandeel abundance and breeding success was found in European shag, guillemot species, razorbill, Atlantic puffin, common tern or Arctic tern.[170][171]

5.2.12 While the breeding success of kittiwakes differed following the Wee Bankie sandeel fishery, it is difficult to distinguish the driver of population dynamics in the natural environment. Pressures such as disease, climate change and weather can all also play a role in population dynamics. The effects of the sandeel fishery may be additive on top of wider environmental processes, particularly climate change, that are reducing sandeel availability to seabirds.[172] Therefore, fisheries closures can provide benefits but environmental processes will also strongly determine seabird breeding success.[170][173]

5.2.13 The positive benefits to seabird productivity and populations of a sandeel fishery closure are difficult to quantify because of the complex relationships between prey and seabird demography, ongoing climate-mediated changes in sandeel population (including from climate change) and the numerous other pressures that seabirds face. There is also considerable variation across seabird species in their dependence upon sandeel and their ability to switch to alternative prey. However, despite these uncertainties, maximising abundance and availability of sandeel stocks as prey for seabirds in Scotland remains a key mechanism by which resilience in seabird populations might be achieved.

Potential effects on marine mammals

5.2.14 Sandeel are a key prey species for marine mammals in Scottish waters, comprising a large proportion of the diet of seals and some cetaceans.[174][175][176] However, the importance of sandeel to marine mammal diet varies considerably with species and season.

5.2.15 Grey seals and harbour seals are largely sympatric within the UK, occupying similar ecological niches with some degree of regional spatial partitioning. This is marked by a notable overlap in diet throughout the UK populations where sandeel and large gadids are proportionally the most represented prey groups by weight, in both species.[177][178][179][180][181]

5.2.16 Scat analysis studies have concluded that sandeel dominate the diet of grey seals in all regions during autumn and winter except for the Inner Hebrides where gadids predominated.[182] However, this dominance shifts to gadids and other benthic species during the spring and summer in Orkney and Shetland, and drops from 22.2% to 8% of the diet of grey seals in the inner Hebrides. For harbour seals, sandeel were also dominant but with regional variation. In the Moray Firth, sandeel were dominant in harbour seal scats across all seasons. However, the data suggested that sandeel became less important in more southerly regions with flatfish and gadids predominating in south-east Scotland, the southern North Sea and the Inner Hebrides. In addition, harbour seals from the Outer Hebrides and Shetland preferred pelagic species with sandeel only representing 13.1% and 23.7% of the diet in these regions during the spring and summer months. This prevalence does increase during autumn and winter in Shetland where sandeel become the preferred prey of harbour seals, representing 31.5% of their diet.[182]

5.2.17 It has been suggested that the decline in harbour seal abundance in the North Sea may be linked to a reduction in sandeel stocks. Specifically, there appears to be a correlation between regional declines of sandeel stocks (northern and eastern Scotland) and the declining populations of harbour seals in eastern Scotland and Orkney, where sandeel dominate the diet of harbour seals. This relationship with sandeel stock levels was supported by findings that the diet of harbour seals appeared more diverse in areas where harbour seals are not in decline (West of Scotland). If sandeel are in short supply, it has been proposed that grey seals may out compete harbour seals thereby contributing to their decline given grey seal preference for sandeel in these regions.[182]

5.2.18 Harbour porpoises (Phocoena phocoena) in Scottish waters have been found to feed predominately on whiting and sandeel[183][184] with sandeel being particularly important during the spring and summer.[184]

5.2.19 A diet study on stomach contents of ten stranded minke whales (Balaenoptera acutorostrata) in Scotland showed that sandeel were the most important prey. species and contributed two-thirds of the individual diet, by weight diet.[185] These findings have been supported by other studies in the wider North Sea region. For example, sandeel were found to comprise 86.7% of the weight of the prey species found in the stomach contents of minke whales caught by Norwegian whalers in 1999[186] and were also found to dominate the diet of minke whales caught in the North Sea.[187] However, the proportion of sandeel dominance appeared to change between years, with one year showing a complete absence of sandeel in favour of a dominance of mackerel. Further, the importance of sandeel appeared to diminish through the sampling years, which was suggested to be linked to the poorer availability of sandeel in contemporary years.[187]

5.2.20 Sandeel were present in a diet study of a small number of white beaked dolphins (Lagenorhynchus albirostris),[188] but gadids are thought to be the predominant prey items in the North Sea.[189][190] Sandeel are not thought to be a major component of the diet of bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus).[191]

5.2.21 Sandeel are an abundant, but declining food source in much of the distributional ranges of the marine mammal species described above. However, the reliance on sandeel and subsequent susceptibility to fluctuations in sandeel abundance and distribution differ among marine mammal species, owing to variations in their ecological niches and dietary plasticity. Furthermore, the varying vulnerability of marine mammals to declines in sandeel abundance is a complex and stochastic interaction between prey distributions, diet, predator and prey demography, and predator foraging distributions and behaviour[192] so predictions are subject to considerable uncertainty.

5.2.22 Sandeel are a high-quality, lipid-rich prey source[193] and improved body condition in marine mammals is linked to the proportion of sandeel in their diet. For example, a correlation was found between harbour porpoises in better body condition and higher amounts of fatty fish in their diet.[194] Links between consumption of sandeel and health status of porpoises also suggested that a decrease in sandeel availability could have negative effects on porpoise populations.[193] The predicted consumption of sandeel is high in porpoise diets, despite an abundance of other available prey species. Further, consumption of sandeel is significantly greater than all other prey types even when abundances are roughly equal.[195] Multi-species functional responses have been published, describing the relationship between harbour porpoise and their prey species in the North Sea. These have indicated that when energy rich prey-species (i.e., sandeel) are scarce, porpoises must increase the total biomass consumed to avoid shortfalls in energy intake[195] and by extension, poor body condition. As a result, minor differences in overall biomass and energetic intake were predicted between 2011 and 2022 (a period of pronounced sandeel decline in abundance across their range). Porpoise may subsequently travel greater distances or shift their ranges in search of a higher biomass of prey or increased densities of other high energy prey, partially explaining the southward distributional shifts of porpoise in the North Sea between 1994 and 2005 when sandeel in the SA4 region also showed pronounced declines.[196][197]

5.2.23 Declines in sandeel stocks could have implications on inter-specific competition between marine mammal species in situations where sandeel are the primary food source. If sandeel are scarce, the considerable overlap in diet between grey and harbour seals[192] could result in exploitative competition which could impact one or both species. With harbour seals noted to be in significant decline in certain regions of Scotland, a depletion in sandeel stocks could be a factor in the further decline of harbour seals as indicated by the continuing decline in areas where seals show high preference for sandeel and little plasticity in diet.[192] The compounded effects could hasten the decline in certain populations, rendering conservation effort increasingly challenging.[198]

5.2.24 Identifying an effect of the sandeel fishery or a reduction in fishing pressure is difficult as it involves complex interactions between multiple drivers of both sandeel and predator dynamics. Further, data on the effects of sandeel abundance on marine mammal population sizes, foraging ecology and distribution are limited, with few studies able to garner sufficient statistical power to identify significant relationships. However, it seems a reasonable assumption that any increase in sandeel abundance that might result from a reduction in fisheries pressure might be beneficial to several populations of marine mammals given their dependence on sandeel as a prey source.

Potential effects on sandeel

5.2.25 Causes of variation in sandeel abundance are numerous and are driven by fishing mortality and (principally) natural mortality, the latter being influenced by factors such as environmental change (temperature effects, regime shifts) and top-down processes (trophic regulation by marine predators). Evidence shows that causes of variation in natural mortality played a more prominent role than fishing mortality in shaping sandeel abundance in Scottish waters and as these causes of variation are rarely accounted for, an effect of fishing pressure on sandeel abundance is rarely observed. However, while results should be considered with caution due to limited data availability, age 1 sandeel seem to have a higher survival rate in the current fishery closure.

5.2.26 While the effect of a fishery closure may be difficult to observe in a changing environment, sandeel are likely to benefit from spatial management measures aimed at reducing fishing mortality due to their life-long attachment to particular sand banks and limited dispersal and movements.

5.2.27 Variations in Spawning Stock Biomass (SSB) are mainly driven by variability in recruitment. Recruitment, to a certain extent, is contingent on the size of the reproductive population (SSB). Environmental change has a multitude of effects (direct and indirect) and can affect SSB through the maturation process; recruitment through the effects on phenology (spawning date, incubation time, hatching date); and trophic mismatch between sandeel hatching and the availability of their copepod prey. The fishery can directly affect SSB through fishing mortality and there is some evidence that it may also indirectly affect recruitment by decreasing SSB (through mortality) or by reducing the abundance of large individuals which have a higher fecundity and may spawn earlier (which in turn may affect trophic mismatch and interact with climate change effects). A fishery closure may therefore promote sandeel resilience to climate change by limiting variation in SSB that might affect recruitment and ensuring that sufficient large, early spawning individuals are present in the population. In accordance, a modelling study found that population collapse was more likely under exploitation.[199]

Potential effects on predatory fish

5.2.28 Predatory fish are often generalist feeders, where the diet typically consists of no more than 20% of any species,, as predators switch between prey species based on availability.[200][201] The importance of sandeel as a food source is more variable for predatory fish than for seabirds and mammals. Some fish species such as whiting, haddock, cod, plaice, lesser weever and grey gurnard have shown higher body condition indices or growth in years of high sandeel abundances.[202][203] Body condition relates to growth, survival and reproduction and can thereby affect fitness and abundance of predators.

Potential effects on other fish caught by the sandeel fishery

5.2.29 Whiting and mackerel are caught as bycatches in the sandeel fishery and whiting aggregate at sites of high sandeel abundance.[204] It is expected that any benefits realised to sandeel through the closure of the sandeel fishery may be realised for whiting and mackerel also, although it is expected that these benefits would be to a lesser extent than for sandeel as they are not the target species of this fishery.

Other benefits

5.2.30 Sandeel are a protected feature of the following Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) - Mousa to Boddam MPA, North-west Orkney MPA and Turbot Bank MPA.[205] Several MPAs also aim to conserve sandeel habitat to ensure the continued supply of young recruits to other sandeel grounds across Scotland and the rest of the UK. The increased protection that will result from the closure of the sandeel fishery will benefit these MPAs through assisting the delivery of their conservation objectives.

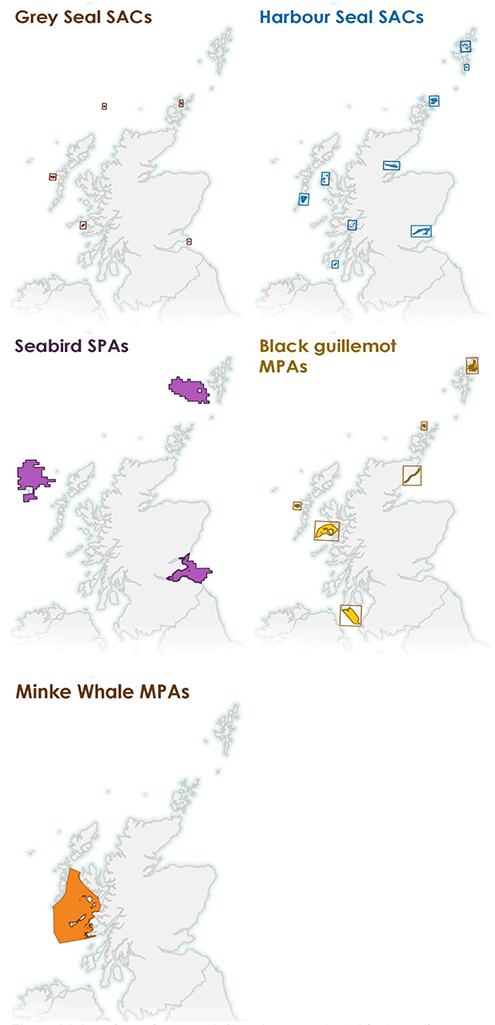

5.2.31 There are conservation measures in place for several species that rely on sandeel as a source of prey, including Special Areas of conservation (SACs) for grey and harbour seal, Special Protected Areas for seabird species, and MPAs for Black guillemot species and minke whale (Figure 34).[206] The increased protection that will result from the closure of the sandeel fishery will help ensure that conditions within these sites are supportive of the conservation site objectives through supporting the availability of prey species.

5.2.32 Overall, the increased protection that will result from the extension of the closure of the sandeel fishery to all Scottish waters will provide potential environmental benefits for the overarching topics of Biodiversity, Flora and Fauna, and Water quality, Resources, and Ecological status (Table 8), and contribute to the achievement of the SEA objectives (Table 9).

5.2.33 The implementation of this management measure may also result in the potential displacement of sandeel fishing activity and its associated pressures outside the boundary of Scottish waters. The closest sandeel fishing waters are in Northeast English waters. The UK government is currently leading their own consultation on the closure of the sandeel fishery in all English waters.[207] If the results of the consultation support closure this would mitigate any displacement effects to English waters. Effects of displacement to the wider North Sea are harder to predict due to the transboundary nature of any displacement.

Table 8: Overall assessment of proposals to close fishing for sandeel in all Scottish waters

SEA Topic: Biodiversity, Flora and Fauna

Assessment

It is assessed that extending the closure of the sandeel fishery to all Scottish waters has the potential to bring about moderate beneficial effects to marine biodiversity. This assessment takes into account the following factors:

Medium spatial scale

Fishing activity in Scottish waters is currently contained within Sandeel Area 4. Therefore, although the closure area proposed is all Scottish waters, the majority of benefits are expected to be delivered within the region of Sandeel Area 4. Extension to all of Scottish waters prevents the risk of adverse effects being realised via displacement of fishing effort to novel fishing grounds outside of Sandeel Area 4.

Long-term

The closure is expected to be permanent once in place, although this will be subject to views collected during consultation. Due to stochasticity of fish population dynamics it is expected that any increase in the sandeel population will not be immediate. It is expected therefore that benefits to species that include sandeel as a prey source will not become apparent upon closure but may become apparent several years post-closure.

Moderate sensitivity to management measure

An increased availability of sandeel may result in benefits to species that include them as a prey source. However, many of these species are sensitive to other pressures that may be a larger driver of their population dynamics than prey availability (see Section 4.2). While an increased prey availability may incur increased resilience to other pressures, the adverse effects of external pressures may outweigh the benefits of increased prey availability achieved through the proposed management measure.

While increased prey availability is a likely outcome of the proposed management measure, other factors affecting sandeel population dynamics could outweigh the effects of fishery closure meaning that increased prey availability is not guaranteed.

SEA Topic: Water Quality, Resources, and Ecological Status

Assessment

It is assessed that extending the closure of the sandeel fishery to all Scottish waters has the potential to bring about moderate beneficial effects to marine resources. This assessment takes into account the following factors:

Medium spatial scale

Fishing activity in Scottish waters is currently contained within Sandeel Area 4. Therefore, although the closure area proposed is all Scottish waters, the majority of benefits are expected to be delivered within the region of Sandeel Area 4. Extension to all of Scottish waters prevents the risk of adverse effects being realised via displacement of fishing effort to novel fishing grounds outside of Sandeel Area 4.

Long-term

The closure is expected to be permanent once in place. Due to stochasticity of fish population dynamics it is expected that benefits to sandeel and other commercially important fish will not become apparent upon closure but may become apparent over several years post-closure.

Moderate sensitivity to management measure

The closure will likely result in benefits to sandeel and other commercially important fish. However, these species are sensitive to other pressures including climate change which may be a larger driver of population dynamics than fishing pressure (see Section 4.2).

Table 9: Contribution of the proposed measure to SEA objectives.

1. To safeguard and enhance marine and coastal ecosystems, including species, habitats and their interactions

Met/not met: Yes

Rationale: This measure will safeguard the sandeel population in Scottish waters and could potentially enhance populations of Scottish seabirds, marine mammals and other species of fish.

2. To maintain or work towards achieving 'Good Environmental Status' for biodiversity

Met/not met: Yes

Rationale: This measure will potentially benefit a wide range of marine species including marine mammals, seabirds and fish species through alleviating fishing pressure on a species that forms the base of marine food webs.

3. To maintain or work towards achieving 'Good Environmental Status' for relevant commercial fish

Met/not met: Yes

Rationale: This measure will directly benefit sandeel by alleviating fishing pressure and will potentially benefit other commercially fished species that predate on sandeel.

4. To protect and conserve the ecosystems and biological diversity of UK territorial seas

Met/not met: Yes

Rationale: This measure will bring potential benefits for the sandeel population and the species which it supports.

5. To deliver sustainable management of fisheries that takes account of the protection of biodiversity and healthy functioning marine ecosystems

Met/not met: Yes

Rationale: By stopping fishing for sandeel in Scottish waters this measure will alleviate pressure on a species that is a key prey source and is therefore vital to the healthy functioning of marine ecosystems.

5.3 Reasonable alternatives

5.3.1 Further to the potential benefits afforded by the extension of the existing sandeel closure to all Scottish waters described in Section 5.2, a detailed assessment of all the potential additional environmental effects that might arise from the scenarios that have been identified as reasonable alternatives (see Section 3.4) has been undertaken and is included in Appendix A. This has included an assessment of the contribution of each scenario to the achievement of individual SEA objectives.

5.3.2 In addition to the potential environmental benefits that will result from the extension of the existing sandeel fishery closure to all Scottish waters (see Section 5.2), Option 2 (extension of existing closure to all of Area 4; see Table 10) will provide no further positive impact to the area of the proposed closure when compared to the proposed closure of all Scottish waters and may have detrimental effects on the areas outside Sandeel Area 4a due to the potential for displaced fishing activity to these areas.

5.3.3 Option 3 (seasonal closures of all Scottish waters to sandeel fishing; see Table 11) will provide no further positive impacts to the area of the proposed closure, but also no negative impacts. This is because the sandeel closure is a seasonal fishery and so seasonal closures are not expected to have any different effect compared to the proposed all-year closure. A full-year closure is preferable in case fishing patterns change in the future.

5.3.4 Option 4 (Voluntary measure; see Table 12) may provide similar environmental benefits to the area of the proposed closure, however this has been considered to be a complex option that would require ongoing management costs of maintaining the voluntary closure agreement. The benefits provided by alternative 3 may be shorter term than the proposed closure, which provides a more permanent option.

5.3.5 Option 0 (do nothing; see Table 13) does not provide any additional benefits and therefore does not meet the objectives of the proposed closure. Alternative 4 may also result in detrimental effects due to displacement of fishing effort into Scottish waters if the UK Government decides to close their waters to sandeel fishing following the outcome of their consultation which took place earlier this year.

5.4 Mitigation and monitoring

5.4.1 No significant adverse environmental effects have been identified by the SEA and therefore no mitigation measures are proposed as part of the assessment process.

5.4.2 Existing environmental monitoring programmes will continue following the proposed closure of: the sandeel fishery in all Scottish waters:

- The abundance and distributions of marine mammals from, for example, the Small Cetaceans in European Atlantic Waters (SCANS) surveys and information made available through the Special Committee on Seals (SCOS) reports on populations estimates and trends.

- The abundance and distributions of seabirds, for example from the UK Seabird Monitoring Programme monitoring of breeding seabird species at coastal and inland colonies across the UK.

- The abundance of predatory fish species from information on the overall state of fish stocks made available through ICES annually.

5.4.3 It is important to acknowledge the complexity of marine ecosystems and their interactions with other drivers which may affect population status (such as climate change, weather events, offshore developments, disease outbreaks, etc.) which make it impossible in most cases to isolate any one driver of change.

5.5 Cumulative effects

5.5.1 The 2005 Act requires that the cumulative environmental effects of the extension of the current sandeel closure to all Scottish waters are identified and evaluated. As we are consulting on a single measure, there is no scope for cumulative effects of this proposal. The cumulative effects of this measure have been considered in combination with other existing or developing plans, programmes and/or strategies that fall outside the scope of this proposal.

5.5.2 The vision for Scotland's marine environment as set out in the Biodiversity strategy to 2045[208] is for 'clean, healthy, safe, productive and diverse seas; managed to meet the long term needs of nature and people'. The sandeel fishery closure proposed by this consultation supports this aim through potential benefits for marine biodiversity that may arise from the proposed closure.

5.5.3 There are a number of existing programmes and measures in place to protect Scottish seabirds. This includes a suite of SPAs and MPAs in which seabirds are a protected feature (Figure 26). The Scottish Government is developing the Scottish Seabird Conservation Strategy, which will aim to optimise the conservation prospects of seabirds in Scotland through effective management of existing and emerging threats. The Scottish Government has also developed a HPAI in wild birds response plan which sets out the approach that the Scottish Government and its agencies will take to respond to an outbreak of HPAI in wild birds in Scotland. The sandeel fishery closure proposed by this consultation will potentially support the outcomes of these existing and developing programmes through increasing seabird population resilience to the range of pressures that they face via an increased availability of an important prey species.

5.5.4 A number of existing programmes and measures are also in place to protect cetaceans in Scottish waters, including MPAs in which minke whales are a protected feature (Figure 26). It is an offence to deliberately or recklessly disturb any cetacean under the Conservation (Natural Habitats, &c.) Regulations 1994 (as amended).[209] The Scottish Government is leading on the development of the UK Dolphin and Porpoise Strategy, which aims to ensure that appropriate management is in place to respond to new and emerging pressures affecting cetaceans in UK waters and, in this way, help to maintain their favourable conservation status. Consultation on the strategy concluded in summer 2021.[210] The proposals put forward by this consultation will potentially support the outcomes of these existing and developing programmes through increasing the resilience of cetaceans that consume sandeel to the range of pressures that they face.

5.5.5 A network of SACs are in place to protect both harbour and grey seals (Figure 26). Seals are also granted additional protection from intentional or reckless harassment at 194 designated haul-out sites under the Protection of Seals (Designated Seal Haul-out Sites) (Scotland) Order 2014[211], and are protected from intentional and reckless killing, taking and injury under the Marine (Scotland) Act 2010 Part 6.[212] The Scottish Government has funded research into the drivers of harbour seal decline[213] with the aim of identifying potential drivers of this decline. Potential drivers identified include competition for prey. The proposals put forward by this consultation will potentially support the conservation objectives of SACs by increasing prey availability to seals. Likewise, the proposed closure has the potential to reduce competition between harbour and grey seals by increasing the supply of prey to both species.

5.5.6 Given the importance of sandeel to the wider ecosystem and the subsequent benefit provided by the species in aiding long-term sustainability and resilience of the marine environment, it remains an over-arching and long-held Scottish Government position not to support fishing for sandeel in Scottish waters, which is reflected in Scotland's Future Fisheries Management Strategy. This position was emphasised in June 2021 when the Cabinet Secretary for Rural Affairs and Islands committed in Parliament to considering what management measures could be put in place to better manage the North Sea sandeel fisheries in Scottish waters.

5.5.7 Under the Fisheries Management Strategy 2020 to 2030, the Scottish Government is committed to work with our stakeholders to deliver an ecosystem-based approach to management, including considering additional protections for spawning and juvenile congregation areas and restricting fishing activity or prohibiting fishing for species which are integral components of the marine food web, such as sandeel.[214] The proposals to close fishing for sandeel in all Scottish waters directly support this aim.

5.5.8 The Scottish Government is committed to a plan-led approach to the development of commercial scale offshore wind. The Sectoral Marine Plan for Offshore Wind Energy[215] (SMP-OWE) was adopted by Scottish Ministers in October 2020 and became the spatial footprint for the ScotWind leasing round, managed by Crown Estate Scotland. More recently, the Scottish Government is progressing the Sectoral Marine Plan for Offshore Wind Innovation and Targeted Oil and Gas (INTOG) decarbonisation alongside the Iterative Review of the SMP-OWE. Together, these planning processes will assess the potential impact of the Plan Options (INTOG) and the now know Option Agreements identified by the ScotWind leasing rounds.

5.5.9 Though effort has been taken in the planning process to avoid impact on key seabird species, the scale of potential development identified through ScotWind, in combination with existing developments, indicates that there are likely to be negative impacts on several seabirds species. Many of those seabirds are described above as potentially benefiting from the proposed closure.

5.5.10 The UK Government published their consultation on spatial management measures of industrial sandeel fishing in March 2023 and are currently analysing the responses to this consultation.[216] If the UK Government decides to close English waters in the North Sea to sandeel fishing following the outcome of their consultation then the combination of any measures in English waters and the proposed sandeel closure in all Scottish waters presented here will result in closure of all UK waters to sandeel fishing, if Ministers are minded to pursue the proposed closure. The combined measures will prevent displacement of fishing activity from Scottish into English waters and vice versa, and are expected to result in complimentary environmental benefits.

5.6 Conclusion

5.6.1 Overall, this assessment considers that the increased protection that will result from the extension of the existing sandeel fishery closure to all Scottish waters will potentially provide environmental benefits for the overarching topics 'Biodiversity, Flora and Fauna' and 'Water quality, Resources, and Ecological Status', and will contribute to the achievement of the SEA objectives. This is because the proposed extension has the potential to result in environmental benefits for a range of marine species including sandeel, seabirds, marine mammals and predatory fish.

5.6.2 Consideration of reasonable alternatives showed that several scenarios could result in some of the benefits of full closure being realised, but that the proposed full closure was the most likely scenario to bring about long-term benefits across the themes of Flora, Fauna and Biodiversity and Water Quality, Resources, and Ecological Status. Consideration of alternatives also showed that taking no action poses a risk of adverse environmental effects through the potential for increased fishing effort in Scottish waters as a result of the closure of English waters.

5.6.3 The proposed extension of the sandeel closure to all Scottish waters will likely bring about synergistic benefits to a range of existing and developing policies and programmes including existing protected areas, Future Fisheries Management, and the developing Scottish Seabird Conservation and Dolphin and Porpoise Strategies.

Contact

Email: sandeelconsultation@gov.scot

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback