Scotland's Tax Strategy: Building on our Tax Principles

Sets out the next steps in the evolution of the tax landscape in Scotland, expanding on our framework for tax published in 2021.

Chapter 2 – The Fiscal and Economic Context

In recent years, Scotland has faced significant economic and fiscal challenges which have also been seen across the UK and which have created lasting pressures on our public finances.

These include years of UK Government austerity, the significant economic impact of exiting the European Union, a global pandemic, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and the cost-of-living crisis. The impacts of the inflation and cost-of-living shocks have been persistent, leading to sustained higher price levels and interest rates. Although some of the economic shocks are still unwinding, the economy has reset over this period – with relatively flat economic growth and the impact of higher prices on household finances more pronounced than during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Within the powers available, the Scottish Government has taken extensive steps to ensure that it can deliver a balanced budget each year, whilst continuing to invest in public services and support individuals, households and businesses. The decisions we have made on tax policy since devolution, distinct from the rest of the UK, have raised significant and vital revenues for investment in public services.

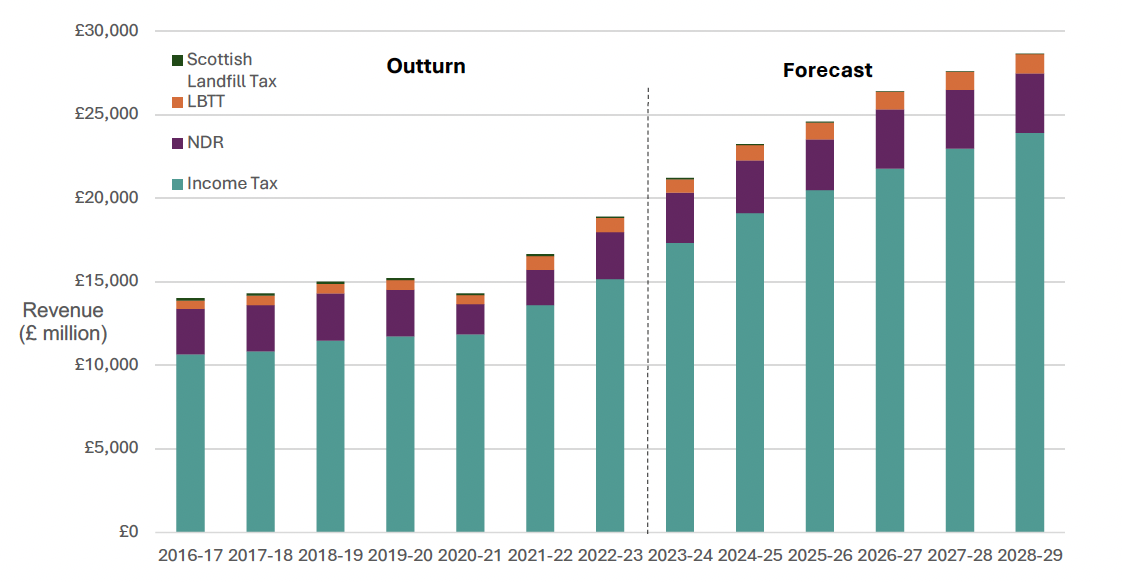

The SFC forecast that devolved tax revenues, including NDR, will raise £24.6 billion in 2025-26, rising to over £30 billion in 2029-30. Figure 1 shows the significant contribution of Income Tax compared to NDR, LBTT and SLfT since the devolution of tax powers in 2016-17. In 2025-26, Income Tax alone will contribute 83% (£20.5bn) of overall tax revenue.

While cross country comparisons of tax are difficult, Scotland and the UK raise substantially less as a proportion of GDP from labour taxation than the EU, but similar to the OECD average[ix]. This results in middle-income earners being taxed less in Scotland and the UK than the OECD average[x].

The strategic, fiscal, and economic challenges that Scotland faces clearly go beyond a single budget cycle and require longer term policy responses.

For example, like many western countries, Scotland’s population structure is ageing and is expected to undergo significant change, with the number of people over 65 projected to grow by 9.8% over the next five years[xii], putting further pressure on public expenditure. Scotland’s working-age population is also projected to fall by roughly eight percentage points over the next 50 years[xiii], affecting the size of the tax base and adding further fiscal pressures over the longer term.

Tax revenues are a vital component of meeting our fiscal challenges, but they are only part of the story. That is why we are progressing the work required to deliver our fiscal strategy and ensure the fiscal position is sustainable: to address the drivers of public spending and focus on driving economic growth, alongside adopting a strategic approach to tax.

Taken together, this will ensure that our spending and investment decisions achieve value for money over the medium term, with sustainable spending plans in place, and the economic conditions to ensure growth in tax revenues.

The importance of economic performance

Economic performance is vital to delivering sustainable tax revenues, with the economy and tax system intrinsically linked. It is our relative performance against the rest of the UK (defined as England and Northern Ireland) which drives our net tax position[xiv] - the amount of spending power that tax contributes to the Budget. If tax revenues per person in Scotland grow faster than those in the rUK, then the Scottish Budget gains. If tax revenues per person in Scotland grow slower, then the Scottish Budget is made relatively worse off.

Several factors can affect Scotland’s net tax position:

- For Income Tax, relative growth in earnings per person and changes in its distribution compared to rUK over time, as well as differences in pensions and property income; the relative growth in the number of taxpayers; and the relative performance of the Scottish labour market.

- For LBTT, the number of properties sold and the average growth in property prices, both of which can be affected by the overall performance of the economy.

- Policy decisions at a Scottish and rUK level. Even if the Scottish Government does not make any policy changes, rUK policy decisions can still have a material impact on the Scottish Budget. For example, if there are changes to the UK-wide Personal Allowance.[xv]

The SFC[xvi] has highlighted the historical growth of Scottish Income Tax relative to the rest of the UK underpinning the net position. Analysis suggests that this was predominately driven by a historical decline in the oil and gas industry in Scotland in the early years of devolution, combined with strong earnings growth associated with the financial services sector in London and the South East.[xvii]

Data from the Pay As You Earn (PAYE) system[xviii] shows that this historical performance gap is closing, with tax and earnings growing faster in Scotland than the rest of the UK over the past two years - partially offsetting some of the relatively slower earnings growth in Scotland.

We are making significant progress in delivering on our ambitions to transform Scotland’s economy, with growth forecasts revised up and business conditions improving. The SFC expect Scottish Income Tax to continue to contribute positively to the overall net tax position, which is set to improve from around £1 billion in 2023-24 to over £2.4 billion in 2029-30. They have flagged some downside risk to the position, as it results from a higher earnings growth forecast compared to the rest of the UK, together with our more progressive tax system.

There is also an important link between local taxation and economic performance. For NDR, rateable values are generally based on the notional market rent for a property and changes in market values are reflected at revaluation. The three yearly revaluation cycle introduced in 2023, along with a one-year tone date, seeks to ensure that rateable values reflect market values as closely as possible. There are also differences in the tax base between England and Scotland: the average rateable value of a property in Scotland is lower than in England.

The Scottish Tax Base 2024-25[xix]

Scottish Income Tax

- Forecast to raise £19.1 billion.

- Estimated that over three in ten adults in Scotland will pay no Scottish Income Tax.

- Higher, Advanced and Top rate taxpayers forecast to make up 22% of all taxpayers and 69% of Scottish Income Tax raised.

Land and Buildings Transaction Tax (LBTT)

- Forecast to raise £909 million.

- £491 million residential (excluding Additional Dwelling Supplement),

- £226 million non-residential

- £192 million Additional Dwelling Supplement (ADS).

- Residential LBTT (excluding ADS) Transactions over £325,000 between April and October made up 18% of transactions and 83% of revenue raised.

- Transactions below the respective zero percent tax thresholds between April and October made up 34% of residential transactions (excluding ADS) and 45% of non-residential transactions.

Non-Domestic Rates (NDR)

- Forecast to raise £3.2 billion from around 260,000 properties.

- Forecast to provide £721 million worth of NDR reliefs, with around a third on the Small Business Bonus Scheme.

Council Tax

- Forecast to raise £3.0 billion.

- Around 2.6 million Chargeable Dwellings.

- Average Council Tax per dwelling £1,310.

- Around 460,000 households estimated to receive some level of Council Tax Reduction.

Contact

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback