Building regulations - proposed review of fire safety topics: consultation

This consultation and the analysis of the responses to its questions will help inform our decisions on policy direction in response to the Cameron House Hotel recommendations and other aspects of Scottish building standards and fire safety regulation and guidance.

2 Consultation proposals

2.1 Consideration given to mandating active fire suppression systems in conversions of historic buildings to use as hotel accommodation

2.1.1. Introduction

Recommendation four of the Fatal Accident Inquiry (FAI) into the deaths of two people following a fire at Cameron House Hotel in 2017, was as follows:

“The Scottish Government should consider introducing for future conversions of historic buildings to be used as hotel accommodation a requirement to have active fire suppression systems installed.”

‘Historic building’ is not currently a term defined in relevant legislation. Accordingly, The Scottish Government has directed that investigation and reporting be based upon the term ‘traditional building’. This is a defined term and is considered to encompass, amongst other types, ‘historic buildings’. It makes reference to construction characteristics that can reasonably be deemed present in that type of building in Scotland.

Traditional building is defined in the Technical Handbooks as “a building or part of a building of a type constructed before or around 1919:

a) using construction techniques that were commonly in use before 1919 and

b) with permeable components, in a way that promotes the dissipation of moisture from the building fabric.”

Traditional buildings may also include buildings that are listed for their special architectural or historic interest.

The expert panel agreed that traditional mass masonry and voids, often between wall and linings, described traditional construction within the context of the FAI recommendations.

2.1.2. Scope of application of proposal

The FAI recommendation has a clear focus on hotels. However, consideration has been given as to whether or not guest houses and bed and breakfast accommodation should be included in the analysis. The general consensus of the expert panel being that small hotels, bed and breakfast establishments and boarding houses are out-with the scope of Recommendation 4, the analysis focuses on hotels.

Meaning of B&B, guest house etc. as defined in fire safety guidance for existing premises with sleeping accommodation (2022) - bed and breakfast premises in the home of a resident operator (for not more than 8 guests) and which in either case, have a means of escape from bedrooms via a traditional ‘hall’ with at least one exit directly to the outside; do not have letting or guest accommodation below a ground floor or above a first floor; do not act as the principal residence for paying guests; and do not have any storey area over 200 m² internal floor space.

2.1.3. Risk to be addressed.

As part of the FAI expert witness evidence, it was noted that:

“all historic buildings and in particular complex structures with several phases of development such as the Hotel pose potentially significant risks. They will not have been constructed to modern standards of structural fire protection and protection against spread of flames, save for a few specialist building types (typically of an industrial nature). Later phases of work, or repairs, will be to differing standards and quality, perhaps compromising previous compartmentation or fire separation measures. These may not be immediately apparent to the lay person, or even to professionals who are not specialists in that field. Even where such risks are known, there are inherent challenges in addressing them to the standards of a new building. To plug every cavity, floor void, gap behind wall and plaster, or oversized pipe duct would be a nearly impossible undertaking in the absence of a complete stripping back of historic floors, walls, and ceiling linings.’

It was also explained that:

“a historic building will have linked cavities or voids. Unless all linings are removed, it is extremely difficult to adequately stop or block these. A building such as the Hotel will, by its nature, present a risk of rapid spread once the flame breaches the wall and ceiling linings. Where there is sleeping accommodation that in turn raises the risk for occupants significantly”.

Two potential responses were set out by the expert witness:

“One option may be for fire escape routes to be relined to ensure the integrity of the linings against fire. In some straightforward buildings that may be practicable. In very complex historic structures, it may not be.”

“An alternative, and one which in my opinion has potentially significant merit, would be to consider the installation of automatic fire suppression systems in cases such as this. Whilst it would not necessarily prevent a fire from breaking out and/or spreading in a cupboard or concealed cavities/voids, such systems would significantly slow the spread of flame within the adjacent apartments and rooms which in turn provides a longer window for the commencement of firefighting. That in turn would extend the margin of safety for available safe escape time, taking account of the occupant behavioural characteristics”.

The expert witness evidence also set out a number of factors which were relevant to Cameron House and which led to recommendation 4:

1. “A complex, multi-phase historic structure where much was unknown about the forms of construction used over time.

2. A complex and convoluted floor plan on the upper storeys of the original or old house.

3. Historic room arrangements, fixtures, and finishes which contributed to the special architectural and historical interest of the property and hence where in-situ preservation was the accepted heritage management policy approach.

4. The presence of interlinked voids as a normal consequence of the traditional construction techniques used and later alterations and which could not necessarily be identified absent widespread stripping-out of historic fabric.

5. The poor performance of some components, notwithstanding their granting of previous regulatory approvals (notably the widespread use of timber lath & plaster on timber strapping).”

The FAI report recognised the danger of rapid spread of fire via cavities and voids and that this resulted in corridors within the hotel becoming heavily smoke-logged only a short time after the alarm activation. It was noted that an alarm system and early instigation of firefighting operations were not, in themselves, sufficient to prevent rapid spread of flame or tragically loss of life.

The FAI determined “that the installation of an active suppression system is a precaution which could reasonably have been taken and which, had it been taken might realistically have resulted in the deaths being avoided”. This led to recommendation 4 being made. It is understood that in making the recommendation, it was not anticipated:

“that sprinklers might be required for all future hotel (or guest house) conversions but rather that there might be a case for them where a similar range of complex, interlinked factors came into play and thus presented a high(er) risk to occupants”.

Fire safety standards specify that occupants, once alerted to the outbreak of the fire, are provided with the opportunity to escape from the building, before being affected by fire or smoke. In the context of an existing traditional building converted for use as a hotel, this generally requires a need for detailed appraisal of the risk factors of the building under consideration.

It is understood that ‘complex, interlinked factors’, referred to in evidence, relates to attributes that increase the likelihood of non-compliance with the current building standards and the need to consider all risk factors holistically.

It may then be possible, for example, to compensate for any identified deficiency in escape route travel distance or layout or combustibility of materials etc. by use of enhanced automatic fire detection and suppression systems to provide early warning and early intervention, and so support means of escape. But again, in the context of adopting the holistic approach for all influencing risk factors, for example, fire and smoke spread through hidden voids and cavities (which may require intrusive investigation to identify) may bypass any compartmentation measures, even with suppression being installed.

Further, proposed guidance on associated risk factors for traditional buildings converted to hotel use are also provided within section 2.1.8, in the context of Option 2.

2.1.4. Building regulations and conversions

The Building (Scotland) Regulations 2004 apply to the design, construction or demolition of a building, the provision of services, fittings or equipment in or in connection with a building, and the conversion of a building. A building warrant is required for all building work unless the work falls under either regulation 3 or 5.

Changes in occupation or use of buildings set out in Schedule 2 of the Building (Scotland) Regulations 2004 list 10 conversion types. Conversion Types 4, 6, 7 and 9 would include conversions of traditional buildings to residential buildings (as defined in the Technical Handbooks as “a building, other than a domestic building, having sleeping accommodation.”), including hotels and so are relevant to Recommendation four (and five) of the Cameron House Hotel FAI.

The existing legislation under Schedule 2 of the 2004 regulations would cover most (if not all) conversions of traditional buildings to residential buildings (including hotels).

Where a building warrant for a conversion is required, the building “shall meet” the requirements of the mandatory building standards or “must be improved to as close to the requirement of that standard as is reasonably practicable, and in no case be worse than before the conversion.” (Schedule 6 of the 2004 Regulations).

Reasonably practicable is defined in the Technical Handbooks and means “in relation to the carrying out of any work, means reasonably practicable having regard to all the circumstances including the expense involved in carrying out the work.”

The general intent is to recognise the challenges that conversions can create in achieving compliance with some mandatory building standards and the supporting guidance in the Technical Handbooks. In some cases conversion of traditional buildings to hotels may not be feasible.

2.1.5. The role of Automatic Fire Suppression Systems

Building Standard 2.15 (Automatic fire suppression systems) is a prescriptive standard which states that “Every building must be designed and constructed in such a way that, in the event of an outbreak of fire within the building, fire growth will be inhibited by the operation of an automatic fire suppression system.” At present, the requirement for suppression is limited to certain types of buildings and does not include hotels.

Automatic Fire Suppression Systems (AFSS) help to control the intensity and size of a fire, suppress it and in some cases may even extinguish it. It can provide occupants with the additional time necessary to escape following the outbreak of fire. The primary role of the AFSS is for life safety but AFSS can also reduce the damage and disruption caused by fire. Automatic fire suppression systems react to heat therefore, the greatest protection is afforded to those occupants out-with the room of fire origin.

Automatic suppression may provide some benefit to occupants in the room of fire origin where for example the fire growth is fast, and the temperatures allow the suppression system to open early in the development phase of the fire. The spray pattern delivered from the heads should control fire spread, reduce temperatures and dilute the smoke. There are alternative forms of automatic suppression available on the market. Each system should be assessed on their own merits and certified and tested to suit its intended use.

The expert panel agreed that a sprinkler system designed to BS EN 12845 would be one of the key standards to apply to hotels of the scale and complexity envisaged by Recommendation 4 of the FAI.

As part of the consideration of recommendation 4, research Automatic Fire Suppression System installations - traditional building conversion to hotels: cost benefit analysis - gov.scot has been undertaken. The research shows that for traditional buildings, the benefits outweigh the costs if the AFSS is installed to BS 9251 direct off the mains supply. When the system is installed to BS 12845, the costs significantly outweigh the benefits where a tank and pump is required

2.1.6. Options to consider

Recommendation 4 is currently being considered as intended to apply to either:

- all instances of future traditional buildings converted to hotel use (which would be in Regulation, as a limitation within Mandatory Standard 2.15), or

- focused to those future conversions of traditional building to hotel use with complex and interlinked factors which present a high risk to occupants (and so incorporated as additional guidance within the Non-domestic Technical Handbook under clause 2.0.7 alternative approach and sub heading for existing and traditional buildings and/or alternatively within the guidance for Mandatory Standard 2.15).

Two options have been identified:

- Option 1 - mandate active fire suppression for conversions of traditional buildings to hotel accommodation; or

- Option 2 - set out a performance/ risk-based approach to determine the case-specific need for suppression with further strengthening of existing Technical Handbook guidance, encouraging an awareness and adoption of wider guidance and promoting the need for competent persons, including independent specialist 3rd parties where appropriate.

In both cases, it is proposed that the extent of provision of AFSS would be within the building being converted but not within additional new construction, such as an extension, where fire safety provisions would be as for new construction.

Commentary on both options is provided below for your consideration. Please consider each and confirm your preferred option in the questions which follow.

2.1.7. Option 1 - Mandate Suppression on conversion of a traditional building to a hotel.

A proposal to mandate suppression would be based on the research evidence ‘Cost benefit analysis for AFSS to be installed when traditional buildings are converted to hotels’.

Advantages of mandating suppression:

- Properly designed and installed for the specific buildings attributes, can provide added life safety protection for occupants of the building.

- Compensates for a range of deficiencies in provisions for means of escape and fire and smoke spread within existing buildings.

- Protects and assists those engaged in fire-fighting and rescue operations.

- Benefits remote properties with reduced fire and rescue availability.

- Helps reduce the disruption to business and local communities in the event of a building fire.

- Reduces water damage (compared to fire hoses) and fire damage (by limiting the early fire growth) to the building.

- Reduces insurance premiums.

Disadvantages of mandating suppression:

- Installation costs.

- Problems with siting and installing adequate water supply tanks.

- Ongoing maintenance costs.

- Contributes to disruption/impact to the historic building fabric during conversion. .

- The benefit from an installation may vary greatly based upon the building construction, size and complexity.

If legislation is required to mandate recommendation 4 of the FAI, a definition of ‘hotel’ may be required. Alternatively introduction of a prescriptive limitation under Standard 2.15 based upon size of premises, e.g. a hotel with more than XX letting bedrooms can be considered.

For example, the following is one example of a definition of ‘Hotel’ in current legislation.

Meaning of hotel - Section 1 (3) in the Hotel Proprietors Act 1956 (legislation.gov.uk), the expression “hotel” means an establishment held out by the proprietor as offering food, drink and, if so required, sleeping accommodation, without special contract, to any traveller presenting himself who appears able and willing to pay a reasonable sum for the services and facilities provided and who is in a fit state to be received.

There are few current legislative reference points for definition of small hotel.

BS EN 16925:2018 Fixed firefighting systems – Automatic residential sprinkler systems – Design, installation and maintenance defines a small hotel as a hotel or guest house with up to 14 lettable rooms and an occupied floor at a height of up to four storeys or 18 m above the lowest fire brigade access level, without a licence to sell alcohol. It should be noted that BSI Committee FSH/18/2 voted against the use of this standard in the UK and have detailed their concerns in the National Foreword to BS EN 16925. BS EN 16925 is not cited in the Technical Handbooks. This includes concerns over the system design and water application. The committee also has concerns about a number of other aspects of EN 16925:2018, where the committee believes that UK practice is more robust than the requirements in EN 16925:2018. Technical Committee FSH/18/2 also draws users' attention to the guidance in the Normative and Informative National Annexes to BS EN 16925 for those using this standard in the UK. It is the intention that the requirements of the National Annexes will render the requirements of BS EN 16925:2018 equivalent to those of BS 9251:2014 for residential and domestic occupancies up to four storeys or 18 m height, whichever is the lower.

2.1.8. Option 2 - Strengthen and add to existing guidance on conversion of a traditional building to a hotel

Strengthen guidance on applying a risk-based / alternative approach to provision of AFSS in conversions of traditional buildings to be used as hotel accommodation.

Performance/risk-based approach to determine the case-specific need for suppression with further strengthening of existing Technical Handbook guidance, encouraging an awareness and adoption of wider guidance and promoting the need for competent persons, including independent specialist 3rd parties where appropriate. Clause 2.0.7 states, in the introduction to section 2 – Fire:

‘The guidance contained within this Technical Handbook indicates one or sometimes more than one means of complying with the mandatory building standards 2.1 to 2.15. In the majority of projects it is envisaged that meeting the guidance will be the usual means of showing that compliance with the building standards has been achieved. However, it should be appreciated that, due to the generic nature of the guidance it cannot cover all building designs or, for example, innovative or new methods of construction. In such cases the designer or engineer will be required to show, by alternative means, that compliance with the building standards will be achieved in the completed building.

It may be appropriate to vary the guidance contained in this Handbook when assessing the guidance against the constraints in existing buildings, especially those buildings which are listed for their special architectural or historic interest. In such cases, it would be appropriate to take into account a range of fire safety measures that are sympathetic to the character of these buildings, whilst ensuring that an appropriate standard of fire safety is achieved.’

Assessment of hazard and risk should be a holistic approach to fire safety features and measures for each particular case and its circumstances.

It is proposed to provide additional guidance to clause 2.0.7 of the Non-domestic Technical Handbook within the ‘existing and traditional buildings’ section and/or Mandatory Standard 2.15 to highlight some common risk factors to consider along with the already referenced HES guidance as part of the overall required holistic performance/risk based approach.

The fundamental challenge for a designer working on such a project is ensuring that they understand enough about the “as built” construction and likely performance of a historic building such as to allow them to make an informed decision about the robustness of the “flexible approach” set out in the Technical Handbook and the HES Guide for Practitioners 6 and 7.

Whilst lath and plaster walls and ceiling can provide effective fire resistance, it is recognised that fire resistance is likely to degrade with time as materials expand and contract due to thermal movement, moisture content and corrosion of fixings. Unprotected service penetrations and poor workmanship may also contribute to the premature collapse of wall and ceiling linings in a fire. Whilst this is not a new concept it should be recognised that the fire performance of materials do change with time and wall and ceiling linings should be inspected throughout the life of the building by a suitably competent professional surveyor, fire risk assessor or engineer with experience in fire safety to ensure the wall and ceiling linings, fire resistance and compartmentation remains fit for purpose. Alternative fire safety measures such as enhanced automatic fire detection and alarm systems and automatic fire suppressions systems can be used to mitigate fire risk where the fire risk assessment falls below the current benchmark standards and guidance contained in the Technical Handbooks. Fire engineering principles and practice is often used in complex traditional or heritage buildings due to their unique challenges and character.

2.1.9. Proposed addition of further guidance in support of Option 2

The current (relevant) guidance within 2.0.7 ‘Alternative approaches’ states:

“Traditional buildings may have interconnected hidden voids (cavities) that require to be ventilated to control moisture in the building fabric. Where the cavities are lined with combustible material e.g. timber lath behind plaster, this increases the risk of rapid fire spread in those hidden voids behind the wall and ceiling linings. Open state or intumescent cavity barriers allow through ventilation in their passive role and inhibit fire spread when activated by heat. However, they may not be the most practical solution in all cases especially where the building has features of architectural character or historic interest which should not be disturbed. Other challenges with conversions of traditional buildings may include for example, fire compartmentation, structural fire protection (fire resistance), fire spread on internal surfaces (reaction to fire) or where travel distance may be excessive.

An automatic fire suppression system can be an effective measure in controlling fire spread and can be a cost-effective solution for reducing the risks created by the conversion of traditional buildings both from life safety and property protection perspectives. The automatic fire suppression system should limit fire growth, extend the time taken until untenable conditions is reached and hence give more time for occupants to evacuate the building. Therefore, where there are deviations from the guidance, it may be more appropriate to install an automatic fire suppression system (see guidance to standard 2.15) and a Category L1 automatic fire detection and alarm system to BS 5839-1: 2017 to ensure the earliest possible warning in the event of an outbreak of fire.

Whilst each building will need to be considered on its own merits, more detailed planning and technical guidance on managing change and conversions in the historic environment is available at:

- Managing Change in the Historic Environment - Fire and Historic Buildings (2023)

- Guide for Practitioners 6: Conversion of Traditional Buildings (2007) – currently being updated with publication expected in 2026

- Guide for Practitioners 7: Fire Safety Management in Traditional Buildings (2010)

A guide to Fire Safety in Traditional Buildings for Dutyholders is currently being drafted by Historic Environment Scotland. This guide will also be targeted at planners, owners, entry level practitioners and other professionals, and is expected to be published in Winter/Spring 2024/25”.

The proposed additional guidance within 2.0.7 ‘Alternative approaches’ would state:

For historic buildings and traditional buildings, which also require sensitive application of the standards, the judgement of what is reasonably practicable must be made in a wider context and recognising that it may be difficult for existing buildings to be reasonably and practicably altered to meet all aspects of current standards. There is no prescribed process for reasonably practicable which can cover all eventualities and situations, however, some commonplace risks as part of the holistic ‘weighing up’ or professional and competent judgment of risk(s) versus proportionate measures to minimise risk(s) to life in the context of existing or traditional buildings, are provided within the listed HES documents above with some notable risk factors also highlighted below.

Notable risk factors which should be considered in conjunction with HES guidance documents listed above and the Non-domestic Technical Handbook guidance, in the context of conversion of traditional buildings to hotel use are as follows:

- A traditional or historic building will generally have linked cavities or voids. Unless all linings are removed (which may be impractical for both heritage and cost reasons), it is difficult to adequately identify and firestop these. The common construction of walls lined with lath and plaster on timber straps fixed to the masonry, leaving a cavity presents a risk of rapid spread once the flame breaches the wall and ceiling linings. The cavities often link with those present in floors and throughout a building, giving an easy path for fire spread. The fire resistance of floor constructions will often be compromised by the presence of such cavities but sealing the space can be disruptive and may interfere with the natural ventilation necessary to maintain the timber elements in good condition.

- Complexity of the floor plan and routes of escape, including floor height above ground level and travel distances and exit choices.

- Occupancy levels of the building.

- The need for individual appraisal of the building under consideration is paramount and required to understand the forms of construction and connection of voids in what can be complex buildings.

- The poorer fire performance of some components and traditional materials compared to modern standards including as a result of condition with age and maintenance, such as lath and plaster. Traditional plaster, while theoretically giving an adequate level of fire resistance, its condition will vary meaning performance in fire may be unpredictable.

- Forms of construction used such as traditional buildings with timber structures, floors and walls.

- The extent and completeness of compartment walls and floors. It is common for inherent weaknesses in fire integrity to occur: compartments may be incomplete, boundaries between elements (such as floors and walls) may not be sealed and openings in compartment walls may have doors with an inadequate period of fire resistance.

- Highly complex series of different periods of build, differing construction techniques may make it difficult to determine the design and construction which leads to challenges in providing elements to current standards such as separating walls with adequate fire resistance, travel distances or escape routes. Alterations for services may also have compromised fire safety provisions (such as compartment walls being punctured) for example by electrical installations or provision of ventilation or heating services.

- Combustible linings or finishes.

- Large, interlinked roof voids.

- Fire resistance of doors.

- Electrical wiring.

- Unprotected structures/ structural elements.

- Risk of external fire spread, particularly those buildings with combustible facades

- Location (remoteness/access) of the building when considering Fire and Rescue operations

- Knowledge of designers, contractors and verifiers involved in the work. It is recommended that contractors have experience of traditional construction techniques and designers hold specialist accreditation.

Conversion of traditional buildings to be used as hotel accommodation is currently subject to notification under Section 34, where local authorities require to notify the Building Standards Division of such applications being made for building warrant and this will remain as an additional ongoing check and balance on the appropriate qualification and experience of the local authority verifier.

Conversion of a traditional building can be challenging and specialist advice may often be needed on specific risk topics, therefore the performance/risk-based approach requires to also consider any need for 3rd party specialist advice/involvement. These buildings carry inherent risks which may not be immediately apparent even to professionals who are not specialist in that field.

Unless the designer has the ability to strip a substantial proportion of the linings and finishes within an existing building then it is very difficult for them to know where all of these risk elements might be and the extent to which they might compromise the performance of a fire-engineered solution.

Recommendations for improving fire safety, including possible solutions for deviations to the guidance include:

- Where solutions depart from those in guidance, it may be more appropriate to install an automatic fire suppression system (see guidance to standard 2.15) and a Category L1 automatic fire detection and alarm system to BS 5839-1: 2017 to provide the earliest possible warning in the event of an outbreak of fire.

- Suppression is an option in traditional buildings with hidden voids or where fire protection does not meet current standards or where suppression is proposed as part of a fire engineered design solution, as a compensatory feature for departures from standards or guidance.

- Ensure specialist advice is sought (for example designers, contractors, passive fire protection specialists and verifiers) early in the design process. Any on-site investigations are undertaken and recorded.

- Proposals verified by 3rd party specialists (heritage and fire), particularly for those situations where complex and interlinked factors present a high risk to occupants.

- Relining of escape routes and upgrading of other elements to improve fire performance, if practicable.

- While it may be possible to improve the passive fire performance of specific elements, there is likely to be a point beyond which the conservation needs of the building are seen as compromised. In such situations, the use of a fire engineered approach can offer an effective alternative through the use of active fire protection measures which can compensate for deficiencies in any passive measures. It may be possible, for example, to compensate for deficiency in escape route travel distances and combustibility of materials by the use of automatic fire detection and suppression systems to provide early warning to occupants of the outbreak of fire, inhibiting fire growth and hence, increasing time for safe escape.

A proposed additional guidance clause, 2.15.7 Conversion of traditional buildings to hotel use, would state that:

When considering suppression as part of a risk based alternative approach (refer to clause 2.0.7) reference should also be made to Historic Environment Scotland’s Guide for Practitioners 6 “Conversion of Traditional Buildings; Application of Building Standards” and other relevant HES documents citied within this guidance.

Consultation Question 1

Which of the above two options is your preferred approach?

- Option 1 - Mandate active fire suppression to all traditional buildings converted to hotel use.

- Option 2 – Update the Non-domestic Technical Handbook with additional performance/risk-based guidance.

Please select only one answer and provide your reasoning in the box below.

Comments

Consultation Question 2

In the context of Option 1, do you consider the term ‘hotel’ needs to be defined?

- Strongly agree

- Agree

- Neither agree nor disagree

- Disagree

- Strongly Disagree

Please select only one answer and provide your reasoning in the box below.

Comments:

Consultation Question 3

If either mandating AFSS or providing guidance on risk-based alternative approaches, do you consider there is a need to define the size and/or complexity of the building being converted?

- Strongly agree

- Agree

- Neither agree nor disagree

- Disagree

- Strongly Disagree

Please select only one answer and provide your reasoning in the box below.

Comments:

Consultation Question 4

Are there any further comments or observations you wish to make on the topic of provision of AFSS on conversion of traditional buildings to hotels or on the options set out?

- Yes

- No

Please select only one answer. If yes, please add comments below and any background or evidence you consider useful.

Comments:

2.2 Hidden cavities and voids, workmanship age and variations from current standards

2.2.1. Overview

Recommendation five of the Fatal Accident Inquiry (FAI) into the deaths of two people following a fire at Cameron House Hotel in 2017, was as follows:

“The Scottish Government should constitute an expert working group to more fully explore the special risks which existing hotels and similar premises may pose through the presence of hidden cavities or voids, varying standards of workmanship, age, and the variance from current standards and to consider revising the guidance provided by the Scottish Government and others.”

The Expert Panels approach to recommendation five has been to review the guidance for existing hotels and similar premises and the relevant standards and guidance contained in the Non-domestic Technical Handbook.

2.2.2. Building Standards – Non-domestic Technical Handbook

Mandatory Building Standards are contained in Schedule 5 of the building regulations, as amended and are generally expressed in functional terms i.e. statements of functions the completed building must fulfil or allow. For example, Building Standard 2.4 Cavities states that “Every building must be designed and constructed in such a way that in the event of an outbreak of fire within the building, the spread of fire and smoke within cavities in its structure and fabric is inhibited.

Guidance in clause 2.4.2 of the Non-domestic Technical Handbook (NDTH) states: “Every cavity should be divided by cavity barriers so that the maximum distance between cavity barriers is not more than 20 m where the cavity has exposed surfaces which achieve European Classification A1, A2 or B, or 10 m where the cavity has exposed surfaces which achieve European Classification C, D, E or F.”

Additional guidance is provided for buildings containing a sleeping risk in clause 2.4.4 which states “where a roof space cavity or a ceiling void cavity extends over a room intended for sleeping, or over such a room and any other part of the building, cavity barriers should be installed on the same plane as the wall. The intention is to contain the fire within the room of fire origin allowing occupants in other parts of the building to make their escape once the fire alarm has activated. However in cases where this is not the most practical solution, a fire resisting ceiling can be installed as an alternative to cavity barriers (see clause 2.4.5).” Clause 2.4.5 recommends a fire resisting ceiling having at least a short fire resistance duration (30 minutes FR min) in accordance with clause 2.1.16. which recommends that any service penetrations are suitably fire stopped.

Practical application of the standard to existing older buildings is more challenging and this is recognised for buildings being converted. In the case of Building Standard 2.4 Cavities, the building as converted shall meet the requirements of this standard in so far as is reasonably practicable, and in no case be worse than before the conversion (Schedule 6 of the building regulations). The assumption is that the means of inhibiting fire spread within cavities should be investigated and where reasonably practicable, improvements should be made in accordance with the current guidance or by way of an alternative approach (2.0.7) to meet the intent of the mandatory building standard.

This guidance raises a number of questions:

- The guidance does not recognise the risk for fire spread via external windows or doors and entering any roof space above via the roof overhang/eaves detail.

- If a fire resisting ceiling is breached, there is no additional redundancy in the floor void or roof void above.

Regulation 8 of the building regulations, as amended relates to fitness and durability of materials and workmanship and states.

“8. (1) Work to every building designed, constructed and provided with services, fittings and equipment to meet a requirement of regulations 9 to 12 must be carried out in a technically proper and workmanlike manner, and the materials used must be durable and fit for their intended purpose.

(2) All materials, services, fittings and equipment used to comply with a requirement of regulations 9 to 12 must, so far as reasonably practicable, be sufficiently accessible to enable any necessary maintenance or repair work to be carried out.”

Supporting guidance is provided in Section 0.8 of the Technical Handbooks in relation to the performance, fitness of materials and workmanship.

The expert panel agree that the wording in Mandatory Standard 2.4 does not require to be amended and they also do not propose supplementary guidance is required in relation to performance, fitness of materials and workmanship. It was however agreed that clarity on reasonably practicable and required competence would be helpful. To recognise the two questions raised above it is proposed to amend the current guidance on cavity barriers within roof voids above fire resisting ceilings, as described in question 9 below.

2.2.3. Fire (Scotland) Act 2005 and associated regulations and guidance.

Fire safety duties for the majority of existing non-domestic premises in Scotland are set out in the Fire (Scotland) Act 2005 and Fire Safety (Scotland) Regulations 2006. Non-domestic premises include:

- workplaces and commercial premises;

- premises the public have access to; and

- houses in multiple occupation that require a licence.

Hotels are ‘relevant premises’ within the meaning of Section 78 of the Fire (Scotland) Act 2005.

The Scottish Government have produced fire safety guidance for different types of non-domestic premises to help dutyholders understand their responsibilities under fire safety law, carry out a fire safety risk assessment and identify and implement fire safety measures. Relevant guidance includes:

- Guidance on carrying out a fire safety risk assessment (2022) for people responsible for non-domestic premises and houses of multiple occupation (HMO).

- Fire safety guidance for existing premises with sleeping accommodation (2022) provides guidance for those responsible for fire safety in premises which provide sleeping accommodation, including hotels and other non-domestic residential accommodation.

An extract from the guidance relative to hidden voids is provided below:

“187. Many buildings have cavities and voids, sometimes hidden from view, which may allow smoke and fire to spread. Examples are:

- Vertical shafts, lifts and dumb waiters.

- False ceilings, especially if walls do not continue above the ceiling.

- Voids behind wall panelling.

- Unsealed holes in walls and ceilings for pipe work, cables or other services.

- A roof space or attic.

- A duct or any other space used to run services.

188. Potential fire spread through cavities and voids should be assessed and, where practical, examined to see if there are voids that fire and smoke could spread through.

189. Cavity barriers may be necessary to restrict the spread of fire in cavities, particularly for those cavities that could allow fire spread between compartments.”

Paragraph 64 of the guidance refers to listed buildings having special architectural or historic interest and states “alternatives to conventional fire safety measures may be appropriate.” The advice goes onto reference guidance issued by Historic Environment Scotland.

2.2.4. Historic Environment Scotland (HES)

The following HES guides aim to provide advice to practitioners, developers, building owners and local authorities regarding the application of the Building (Scotland) Regulations 2004 to the conversion of traditional buildings:

- Guide for Practitioners 7: Fire Safety Management in Traditional Buildings, 2010

- Managing Change in the Historic Environment - Fire and Historic Buildings (2023)

- Guide for Practitioners 6: Conversion of Traditional Buildings - gov.scot -currently being updated with a view to publication in 2026.

- A guide to Fire Safety in Traditional Buildings for Dutyholders is currently being drafted by Historic Environment Scotland.

Managing Change in the Historic Environment: Fire and Historic Buildings (2023) was published on 31 October 2023. Key considerations for decision-making including the protection of life and cultural significance. High level advice is provided on automatic fire suppression systems and compartmentation.

Part one of the Guide for Practitioners 6: Conversion of Traditional Buildings sets out the principles which underlie the guide giving details of aspects such as what makes a building significant, issues surrounding performance of traditional building materials and a summary of key legislation affecting such buildings. Guidance is provided on the specific risks of hidden voids and how to mitigate those risks. There is limited guidance on automatic fire suppression systems.

Part two of the Guide for Practitioners 6: Conversion of Traditional Buildings covers the application of the Standards that are most likely to have an impact on traditional buildings giving the text of each standard, a commentary of potential influences of the standard on traditional buildings, identifies risks from the standard to the building and recommended approaches to meeting the requirements of the standard. More detailed guidance on the use of automatic fire suppression systems and the dangers of hidden voids and how to mitigate those risks is provided in Part two.

GP6 aims to support the Technical Handbooks by looking at those standards which most typically present challenges to conversion projects and by suggesting ways in which these can be overcome.

Consultation Question 5

We propose that that the wording of paragraph 2.4 of schedule 5 of the Building (Scotland) Regulations 2004 does not require to be amended. Do you:

- Strongly agree

- Agree

- Neither agree nor disagree

- Disagree

- Strongly Disagree

Please select only one answer and provide your reasoning in the box below.

Comments:

Consultation Question 6

The Scottish Government publication Fire safety guidance for existing premises with sleeping accommodation (2022) is currently being reviewed. Please provide any comments on the guidance in the text box below with regard to the special risks which existing hotels and similar premises may pose through the presence of hidden cavities or voids, varying standards of workmanship, age, and the variance from current standards (Recommendation 5 of the Cameron House FAI).

Comments:

Consultation Question 7

Although planned for review it is proposed that the principles set out in current HES guidance remains suitable guidance for special risks which existing hotels and similar premises may pose through the presence of hidden cavities or voids, varying standards of workmanship, age, and the variance from current standards (Recommendation 5 of the Cameron House FAI). Do you:

- Strongly agree

- Agree

- Neither agree nor disagree

- Disagree

- Strongly Disagree

Please select only one answer and provide your reasoning in the box below.

Comments:

Consultation Question 8

We propose to change the guidance in the Non-domestic Technical Handbook to recommend cavity barriers at 10m or 20m centres above fire resisting ceilings depending on the European classification for reaction to fire (A-F) of the surface exposed in the cavity. This provision would not apply to small floor or roof cavities above a fire resisting ceiling that extends throughout the building or compartment up to a maximum of 30 m in any direction. Do you:

- Strongly agree

- Agree

- Neither agree nor disagree

- Disagree

- Strongly Disagree

Please select only one answer and provide your reasoning in the box below.

Comments:

Consultation Question 9

It is proposed that the additional guidance indicated in option 2 of question 1 (clause 2.1.9 of the consultation), on identifying risk and implementing proportionate mitigating measures, be included within clause 2.0.7 (alternative approaches) and clause 2.15.7 (Conversion of traditional buildings to hotel use) of the Non-domestic Technical Handbook to strengthen and add to existing guidance. Do you:

- Strongly agree

- Agree

- Neither agree nor disagree

- Disagree

- Strongly Disagree

Please select only one answer and provide your reasoning in the box below.

Comments:

2.3 Amending the scope of application of mandatory standard 2.15 ‘Automatic Fire Suppression Systems’ to extensions of and conversions to flats, maisonettes or social housing dwellings.

2.3.1. Overview

Mandatory Building Standards are contained in Schedule 5 of the building regulations, as amended and are generally expressed in functional terms i.e. statements of functions the completed building must fulfil or allow. The Building (Scotland) Amendment Regulations 2020 came into force on 1st March 2021. Unlike most mandatory building standards, Standard 2.15: Automatic fire suppression systems is a prescriptive standard which states that:

“Every building must be designed and constructed in such a way that, in the event of an outbreak of fire within the building, fire growth will be inhibited by the operation of an automatic fire suppression system.

Limitation:

This standard applies only to a building which:

a) is an enclosed shopping centre

b) is a residential care building

c) [SSI deletes text but does not amend letters assigned to the following categories]

d) forms the whole or part of a sheltered housing complex

e) is a school building other than a building forming part of an existing school or an extension to a school building where it is not reasonably practicable to install an automatic fire suppression system in that building or extension

f) is a building containing a flat or maisonette

g) is a social housing dwelling, or

h) is a shared multi-occupancy residential building”

Since the introduction of the new categories (f), (g) and (h) to Standard 2.15 on 1 March 2021, the Building Standards Division (BSD) has received a significant number of applications for relaxation or dispensation of the standard for low rise and small-scale conversions and extensions to existing flatted developments.

BSD commissioned a research project ‘Cost Benefit Analysis to Inform Decision Making Process for Limitations to Standard 2.15 Automatic Fire Suppression Systems – Alterations, Extensions and Conversions’. The research considered the circumstances which would support a relaxation or dispensation of Standard 2.15. The outcomes of the work has assisted BSD in the determination of applications for relaxation or dispensation and to develop proposals to amend the standard 2.15 in the longer term. In the shorter term/interim a recent Direction has been issued to local authorities which identifies specific circumstances where the provision of an automatic fire suppression system (AFSS) under standard 2.15 is dispensed with when extending a dwelling or undertaking a conversion to create, or increase the area of, a dwelling. It also identifies the conditions which must be met for the Direction to apply in those circumstances. It is important to note that a relaxation or dispensation of Standard 2.15 would not be supported by BSD in those cases where an automatic fire suppression system is already installed in the building.

There has also been a number of applications for conversion of commercial properties e.g. conversion of office space to flats. Schedule 6 of the 2004 Regulations stipulates that where a building warrant for a conversion is required, the building “shall meet” the requirements of the mandatory building standards or for specified standards in paragraph 3 (currently not including standard 2.15) “must be improved to as close to the requirement of that standard as is reasonably practicable, and in no case be worse than before the conversion.”

Reasonably practicable is defined in the Technical Handbooks and means “in relation to the carrying out of any work, means reasonably practicable having regard to all the circumstances including the expense involved in carrying out the work.”

The general intent is to recognise the challenges that conversions can create in achieving compliance with some mandatory building standards and the supporting guidance in the Technical Handbooks.

The principal function of an automatic fire suppression system (AFSS) is to provide enhanced protection to the occupants in the dwelling of fire origin (first principle) and should always be considered the preferred option. AFSS within dwellings may also be used to protect the common route of escape (second principle). However, it is recognised that the cost of installing an AFSS may be disproportionate to the cost of building work and hence no longer make the project viable. The above research supports this position.

2.3.2. Proposal

It is proposed to amend the limitations of standard 2.15 to take account of the current Direction – Dispensation of Building Regulations (Automatic Fire Suppression Systems) (Scotland) Direction 2024: letter to local authorities - gov.scot

Consultation Question 10

It is proposed to amend standard 2.15 and/or guidance to recognise the current Direction for low risk extensions and conversions to flats, maisonettes and social housing dwellings. Do you:

- Strongly agree

- Agree

- Neither agree nor disagree

- Disagree

- Strongly Disagree

Please select only one answer and provide your reasoning in the box below.

Comments:

2.4 Consideration given to extending the ban of combustible external wall cladding systems to hotels, boarding houses and hostels

2.4.1. Overview

In Scotland a ban on combustible external wall cladding systems was introduced on 1 June 2022 under the Building (Scotland)(Amendment) Regulations 2022. The ban applies to ‘relevant buildings’ as defined in the regulations but excludes hotels, boarding houses and hostels. Relevant building means a building having a storey, or creating a storey (not including roof-top plant areas or any storey consisting exclusively of plant rooms), at least 11 m or more above the ground.

In England, following a review and consultation, The Building etc. (Amendment) (England) Regulations 2022 (the "2022 Regulations") came into force on 1 December 2022. The 2022 Regulations amended the definition of "relevant building" to bring hotels, hostels and boarding houses within the scope of the combustible materials ban from which they were initially excluded. As a result, hotels over 18 m will have to ensure that their external walls meet the same performance requirements as the higher risk buildings already covered by the ban i.e. being A2-s1, d0 or better. The regulations apply to new hotels and existing hotels where building work or refurbishment is taking place on external walls.

Following the change of scope in England to include hotels, hostels and boarding houses, the Scottish Government are seeking to reassess the position on these building types and are currently looking at the evidence base to extend the ban on combustible external wall cladding systems to hotels, boarding houses and hostels in Scotland. This work is being considered as part of the Cameron house hotel expert panel group. The risk of fire spread on the external walls of a hotel building where fire could break-out through a window or door opening and spread onto the external walls with the risk of then bypassing the internal compartment/sub compartment measures used to limit fire and smoke spread for escape purposes is being investigated for the Scottish context. The Building Research Establishment (BRE) have completed phase 1 of the research. Phase 2 work is expected to be underway in early 2025.

Phase 1 of the research has reviewed the incident recording system for Scotland which has identified cases for Phase 2 work. The regulatory impact assessments in support of the extension to the ban for England and Wales have also been reviewed – both generally conclude that fire safety risks will be better identified and managed by developers which will reduce the level of risks in buildings and make buildings safer, but they do not quantify or monetise these risk reductions and benefits stemming from the proposed amendments.

The Building and Fire Safety Expert Working Group await the research results of Phase 2 to arrive at a consensus view on the evidence base to mandate a requirement to extend the ban on combustible external wall cladding systems to hotels, boarding houses and hostels.

Consultation Question 11

Please confirm any evidence, contribution or initial comments that would help towards this policy decision.

Comments:

2.5 Miscellaneous fire safety issues

The Fatal Accident Inquiry (FAI) into the deaths of two people following a fire at Cameron House Hotel in 2017, also raised the following concerns which are dealt with alongside other wider fire safety issues below:

“Other points, such as in respect of lath and plaster wall coverings, the presence of any fire-resistant material, and low-level emergency lighting were not matters explored in evidence to such an extent that this Determination can make any specific finding on these points. Nonetheless these points can be expected to be part of the broader consideration by the expert working group exploring the risks posed by all such buildings used as hotel premises which has been recommended in this Determination.”

2.5.1. Lath and plaster and materials

The fire risks posed by lath and plaster wall and ceiling coverings are covered in the guidance to support building and fire safety regulations, including clause 2.0.7 and most recent updates. Similarly, the fire risks associated with lath and plaster wall and ceiling linings is known and recognised in Historic Environment Scotland (HES) publications. The expert panel further agrees that the guidance referred to in Part 2 of the consultation related to Fire (Scotland) Act 2005 provides adequate advice on the fire performance of materials.

Consultation Question 12

The expert panel proposes the existing guidance is fit for purpose and requires no further action in this context. Do you:

- Strongly agree

- Agree

- Neither agree nor disagree

- Disagree

- Strongly Disagree

Please select only one answer and provide your reasoning in the box below. If you disagree or strongly disagree, please provide any suggestions below on how the current guidance could be improved.

Comments:

2.5.2. Low level emergency lighting

Paragraph 2.10 of schedule 5 of the Building (Scotland) Regulations 2004 states “Every building must be designed and constructed in such a way that in the event of an outbreak of fire within the building, illumination is provided to assist in escape.” This mandatory building standard is considered fit for purpose.

The supporting guidance allows for lighting of escape routes to be provided via artificial lighting supplied by a fire protected circuit or emergency lighting. When an existing building is being converted, the guidance recognises that it may be easier to install self-contained emergency luminaires than to install a protected circuit to the existing lighting system. The guidance cites BS 5266-1 Emergency lighting – Part 1: Code of practice for the emergency lighting of premises. Emergency lighting is usually located at the ceiling level and helps occupants evacuate a building safely in the event of a fire by providing defined levels of lighting to escape routes and exits.

However, low level emergency lighting works in a similar manner but is positioned close to the floor to help building occupants wayfind along escape routes in low visibility conditions during a fire event. The expert panel has proposed that the current requirement for a fire protected circuit be removed, with no need for a separate or fire resisting circuit.

Consultation Question 13

The guidance provided in BS 5266-1 is considered to provide sufficient illumination to assist in escape at low level and satisfy the mandatory standard. Low level way finding systems may be used to supplement protected or emergency lighting and can be considered on a case by case basis as part of the fire risk assessment. It is proposed that this key message is strengthened in existing fire safety guidance.

Do you:

- Strongly agree

- Agree

- Neither agree nor disagree

- Disagree

- Strongly Disagree

Please select only one answer and provide your reasoning in the box below. If you disagree or strongly disagree, please provide any suggestions below on how the current guidance could be improved.

Comments:

Consultation Question 14

The expert panel proposes revision of guidance in standard 2.10 to remove the need for a separate and fire resisting escape route lighting circuit? Do you:

- Strongly agree

- Agree

- Neither agree nor disagree

- Disagree

- Strongly Disagree

Please select only one answer and provide your reasoning in the box below. If you disagree or strongly disagree, please provide any suggestions below on how the current guidance could be improved.

Comments:

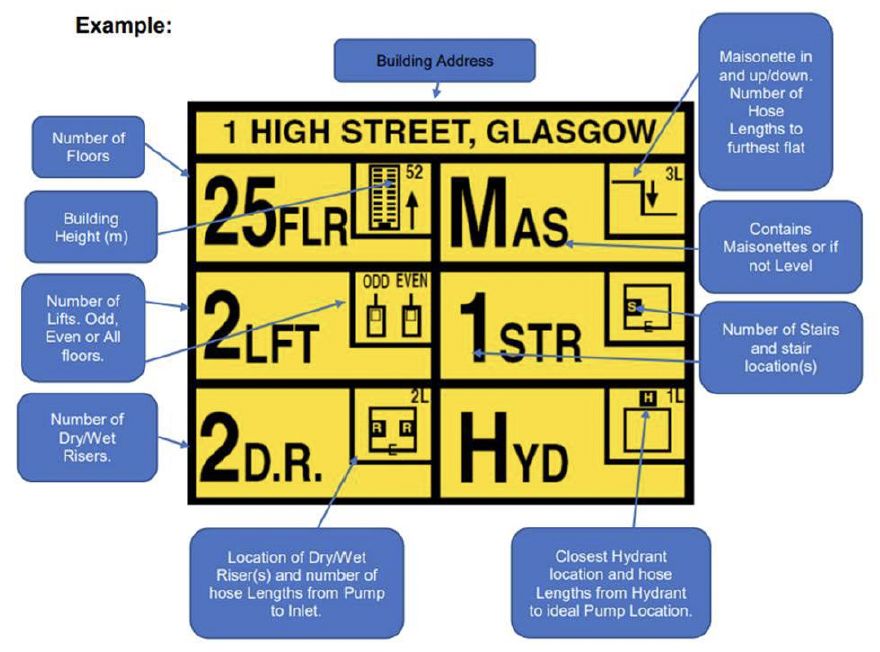

2.5.3. External premises information plates

Mandatory Standard 2.14 Fire and Rescue Service Facilities states “Every building must be designed and constructed in such a way that facilities are provided to assist fire-fighting or rescue operations.”

One of the actions committed to in the Scottish response to the Grenfell Inquiry Phase 1 report was for the Scottish Government to work with stakeholders to ensure external Premises Information Plates were fitted to all high rise domestic buildings in Scotland.

It is proposed to insert a new guidance clause 2.14.10 ‘External Premises Information Plates’ as below to ensure that such a provision is made where a high rise domestic building is constructed or formed by conversion.

New clause: 2.14.10 External Premises Information Plates would state:

All new and converted or refurbished high rise domestic buildings with any storey at a height of more than 18 m above the ground, should have an external premises information plate fitted. It is also recommended that premises information plates are fitted to all existing premises of this type, in accordance with the Practical Fire Safety Guidance For Existing High Rise Domestic Buildings.

These plates display relevant, easy to see information to firefighters attending an incident or carrying out an inspection of a high rise domestic building including confirmation of the address of the building, the number of storeys, position of hydrants and dry risers and relevant information on lifts and escape stairs.

The information plates should be fitted above the main entrance to the building, the colour should be yellow as shown in the example image below and be at least 600 mm by 600 mm in size. They should be made of Di-Bond aluminium composite material. The lettering font should be Helvetica, the text size will vary depending on characters per box but should be clear and readable from ground level. The signs should be affixed to buildings using either screws and wall plugs or a strong weatherproof bonding solution, at a height of no less than 3.5 m above the adjoining ground.

The External Premises Information Plates should contain the following information:

- confirmation of the building address;

- information on whether the premises contains maisonettes (with arrows denoting in and up or in and down);

- the number of hose lengths to the furthest flat;

- number of stairs and their location(s);

- the closest hydrant location and the number of hose lengths to an ideal appliance/pump location;

- location of dry/wet riser(s) and the number of hose lengths from appliance/pump to inlet;

- number of dry/wet risers, number of lifts noting odd, even or all floors served;

- building height in meters (m) and;

- number of floors.

SFRS can be contacted for advice on the layout and information required on an information plate for your premises. Contact details can be found on the SFRS website: Scottish Fire and Rescue Service.

Building Address

- 1 High Syreet, Glasgow

Number of Floors

- 25FLR

Building Height (m)

- 52

Number of Lifts. Odd, Even or All Floors

- Odd

- Even

Number of Dry/Wet Risers

- 2D.R.

Location of Dry/Wet Riser(s) and number of hose Lengths from Pump to Inlet

- E(east)

- 2L

Closest Hydrant location and hose Lengths from Hydrant to ideal Pump Location

- H (hydrant)

- 1L

Number of Stairs and stair location(s)

- 1STR

Contains Maisonettes or if not level

- MAS

Maisonette in and up/down. Number of hose lengths to furthest flat

- 3L

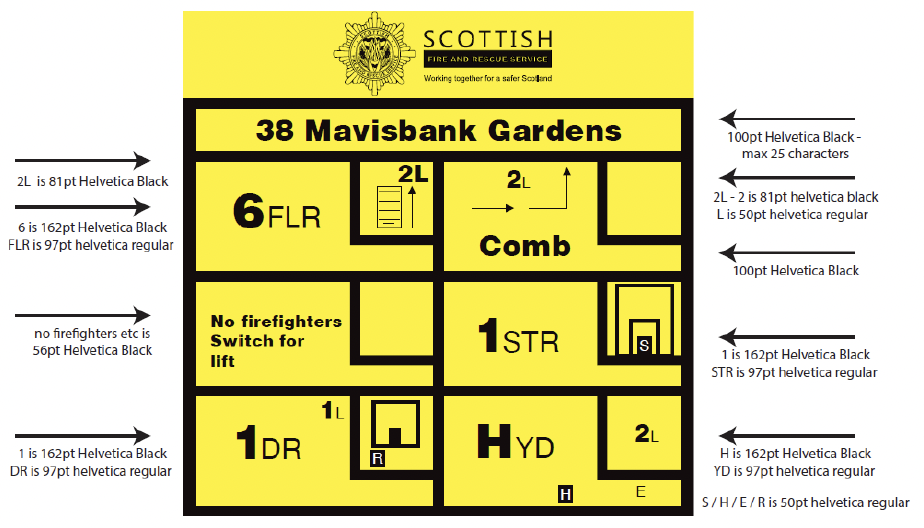

This image denotes best practice size and font types for text on the plates

38 Mavisbank gardens – 100pt Helvetica Black – max 25 characters.

2L – 2 is 81pt Helvetica black. L is 50pt Helvetica regular.

Comb – 100pt Helvetica Black

1STR – 1 is 162pt Helvetica black. STR is 97pt Helvetica black

HYD – H is 162pt Helvetica Black. YD is 97pt Helvetica black

S/H/E/R – 50pt Helvetica regular

1DR – 1 is 162pt Helvetica black. DR is 97pt Helvetica black

No firefighters switch for lift – 56pt Helvetica black

6FLR – 6 is 162pt Helvetica black. FLR is 97pt Helvetica black

2L – 81pt Helvetica black

Consultation Question 15

It is proposed to insert new guidance clause 2.14.10 External Premises Information as detailed. Do you:

- Strongly agree

- Agree

- Neither agree nor disagree

- Disagree

- Strongly Disagree

Please select only one answer and provide your reasoning in the box below. If you disagree or strongly disagree, please provide any suggestions below on how the current guidance could be improved.

Comments:

2.5.4. Clause 2.7.1 of the Domestic and Non-domestic Technical Handbook

Clause 2.7.1 of the Domestic and Non-domestic Technical Handbook provides guidance on what constitutes an ‘external wall cladding system’ (EWCS). This guidance is important as an ‘external wall cladding system’ is referred to in the Building (Scotland) Amendment Regulations 2022 that came into force on 1 June 2022. Unlike England, where the ban on combustible material applies to the entire external wall structure of relevant buildings 18 m or more above the ground, the ban in Scotland applies to external wall cladding systems but not the structural elements in relevant buildings 11 m or more above the ground.

Following industry feedback which has suggested it is unclear if the sheathing or backing board forms part of the EWCS, it is proposed to clarify the guidance in clause 2.7.1 of the Domestic Technical Handbook and Non-domestic Technical Handbook are amended as shown below in bold text.

External wall cladding systems - means non load-bearing components attached to the buildings structure, for example, composite panels, clay or concrete tiles, slates, pre-cast concrete panels, stone panels, masonry, profiled metal sheeting including sandwich panels, rendered external thermally insulated cladding systems, glazing systems, timber panels, weather boarding and ventilated cladding systems. For the purposes of compliance with the building regulations and associated standards, external wall cladding systems also include spandrel panels and infill panels. Many systems incorporate non-loadbearing backing boards or panels, support rails, fixings, thermal insulation, fire barriers and cavity barriers located behind the outer cladding.

Sheathing or backing board - attached to and providing structural support to the forming part of the elements of structure of the building are frame is not considered to form part of the external wall cladding system. For example, a sheathing or backing board that provides racking resistance to the structural frame. However, where combustible sheathing or backing board is proposed in any building with a storey 11 m or more above the ground, a large scale facade fire test should be carried out (see annex 2.B). This is regardless of whether the sheathing or backing board contributes to the structural performance of the building.

Consultation Question 16

It is proposed to amend the wording in 2.7.1 as detailed. Do you:

- Strongly agree

- Agree

- Neither agree nor disagree

- Disagree

- Strongly Disagree

Please select only one answer and provide your reasoning in the box below. If you disagree or strongly disagree, please provide any suggestions below on how the current guidance could be improved.

Comments:

2.5.5. Regulation 8(4) and exemptions to European Classification A1 and A2 components that form part of an external wall cladding system

In June 2022 Regulation 8 was amended so that ‘relevant buildings’ having any storey at a height of more than 11 m above the ground, must be constructed of products which achieve European Classification A1 or A2, subject to some limited exceptions. Following a recent comparison by the Scottish Government of these limited exceptions between Scotland and England, England currently include the following as exemptions when considering the external wall components where Scotland has no equivalent such exemptions when considering the external wall cladding system

- components associated with a solar shading device (which includes brie soleil), excluding components whose primary function is to provide shade or deflect sunlight, such as the awning curtain or slats.

- materials which form the top horizontal floor layer of a balcony which are of European Classification A1 fl or A2 fl-sl (classified in accordance with the reaction to fire classification) provided that the entire layer has an imperforate substrate under it.

To improve UK parity where possible and clarity of Scotland’s exemptions it is proposed to introduce these exemptions into Regulation 8.

Consultation Question 17

It is proposed to amend Regulation 8(4) to align with England (and Wales?) on these two exemptions. Do you:

- Strongly agree

- Agree

- Neither agree nor disagree

- Disagree

- Strongly Disagree

Please select only one answer and provide your reasoning in the box below. If you disagree or strongly disagree, please provide any suggestions below on how the current regulation could be improved.

Comments:

2.5.6. Exit width from rooms in non-domestic buildings

In Scotland (clause 2.9.8), the aggregate unobstructed width in mm of all escape routes from a room should be at least 5.3 mm per person x the occupancy capacity of the room. This assumes a unit width of 530 mm per person at a discharge rate 40 persons per minute. i.e. 530 / (40 x 2.5) = 530 / 100 = 5.3. The largest exit from the room should be discounted and the remaining exits should be wide enough to accommodate this discharge rate. Clause 2.9.8 allows the room exits to be reduced as shown below.

- Where the number of occupants using the escape route is not more than 225, the clear opening width of the doorway should be at least 850 mm.

- Where the number of occupants using the escape route is not more than 100, the clear opening width of the doorway should be at least 800 mm.

However, a number of enquiries have been received on the differences between England and Scotland and summarised in the table below.

Exit width from rooms in non-domestic buildings:

| Maximum number of people | Minimum width (mm) - England (AD B Table 2.3) | Minimum width (mm) - Scotland (clause 2.9.8 NDTH) |

|---|---|---|

| 60 | 750 | 800 |

| 110 | 850 | 850 |

| 220 | 1050 | 850 |

| More than 220 | 5 mm per person | 5.3 mm per person |

Example 1 - Consider a room with an occupant capacity of 200 people. The minimum width required is 200 x 5.3 = 1060 mm. Discounting one exit means that a minimum of two exits are required each having a minimum width of 1060 mm. For 225 people, the minimum width required is 225 x 5.3 = 1192 mm and not 850 mm as permitted by clause 2.9.8.

Example 2 - Consider a room with an occupant capacity of 600 people. The minimum width required is 600 x 5.3 = 3180 mm. The means that 5 x 850 mm exits, discount one leaves 4 x 850 = 3400 mm. However, we know that the discharge rate is based on 40 persons per minute flow rate in 2.5 minutes using a unit width of 530 mm. Since the clear width at each doorway is 850 mm, this means that the occupants can only discharge from the room in single file i.e. 40 x 2.5 x 4 exits = 400 people.

In allowing a reduction of width at doorways as shown in the table above, the consequence is that the occupants will discharge through the exit doorway in single file.

It is proposed to make the following key changes in the NDTH in bold text below NDTH:

1) Where all exits are at least 1.050 in width, the aggregate unobstructed width in mm of all escape routes from a room should be at least 5.3 x the occupancy capacity of the room or storey. This assumes a unit width of 530 mm per person and a rate of discharge of 40 persons per minute. The largest exit from the room should be discounted and the remaining exits should be wide enough to accommodate this discharge rate. For exits less than or equal to 1,050 mm, the exit capacity of each doorway should be as shown below.

2) Where the number of occupants who will use an exit doorway is not more than 225, 200, the clear opening width of the doorway should be at least 1,050 mm.

3) Where the number of occupants who will use an exit doorway is not more than 100, the clear opening width of the doorway should be at least 800 mm.

Consultation Question 18

It is proposed to amend the wording in clause 2.9.8 as detailed. Do you:

- Strongly agree

- Agree

- Neither agree nor disagree

- Disagree

- Strongly Disagree

Please select only one answer and provide your reasoning in the box below. If you disagree or strongly disagree, please provide any suggestions below on how the current guidance could be improved.

Comments:

2.5.7. Hospitals

Building Standards officials have been working with the NHS National Fire safety Advisor on revisions to NHS Scotland Firecode Scottish Health Technical Memorandum 81 Part 1: Fire safety in the design of healthcare premises published in October 2022.

It is proposed to remove the current guidance on hospitals in Annex 2.B of the Non-domestic Technical Handbook and cite SHTM 81 Version 5.0. This will avoid duplication and remove the risk of the guidance diverging.

It is also under consideration to cite

- NHSScotland ‘Firecode’ Scottish Health Technical Memorandum 81 Part 2 – Guidance on the fire engineering of healthcare premises ; and

- NHSScotland ‘Firecode’ Scottish Health Technical Memorandum 81 Part 3: Atria in healthcare premises.

Consultation Question 19

To avoid conflicting information and recognise current practice, it is proposed to remove the guidance in Annex 2.B of the NDTH and cite SHTM 81 Part 1 for new build hospitals. Do you:

- Strongly agree

- Agree

- Neither agree nor disagree

- Disagree

- Strongly Disagree

Please select only one answer and provide your reasoning in the box below. If you disagree or strongly disagree, please provide any suggestions below on how the current guidance could be improved.

Comments:

Consultation Question 20

It is also being considered to cite SHTM 81 Part 2 and 3. Do you:

- Strongly agree

- Agree

- Neither agree nor disagree

- Disagree

- Strongly Disagree

Please select only one answer and provide your reasoning in the box below. If you disagree or strongly disagree, please provide any suggestions below on how the current guidance could be improved.

Comments:

2.5.8. BS EN 13637:2015 Electrically controlled exit systems for use on escape routes

Electric locking and access control is becoming more prevalent and buildings are containing more security features for doors on escape routes and those having to be operated in an emergency.

Panic exit devices to BS EN 1125 are intended primarily for buildings where the public are likely to be present and a panic situation could arise if the building must be evacuated quickly. For this reason, the devices are designed to operate by body pressure alone and require no knowledge of their operation to enable safe and effective evacuation of a building.

Emergency exit devices to BS EN 179 are intended for escape from buildings where the public are unlikely to be present, and where the staff in the building have been trained both in emergency procedures and in the use of the specific emergency exit devices fitted. For this reason, panic situations are considered unlikely, and these devices are therefore permitted to have higher operating forces and do not have to release by body pressure alone.

All panic and emergency exit devices will provide a basic level of security against intrusion, but there is increasingly a need for higher security in buildings such as supermarkets and stores with high insured content, and even in schools and hospitals to protect the occupants against the attentions of intruders or to prevent the occupants from wandering out of the building.

BS EN 13637 ‘Electrically controlled exit systems for use on escape routes’ provides guidance on safe ways of combining physical security with effective means of escape. This increase in security provision, helps to avoid unsafe locking practices, for example, using additional padlocks and chains. These electronic devices should always be discussed with local building standards and fire authorities and will generally be determined on a building occupancy and risk assessment basis.

BS EN 13637 specifies the requirements for the performance and testing of electrically controlled exit systems, specifically designed for use in an emergency or panic situation in escape routes. These electrically controlled exit systems consist of at least the following elements, separate or combined:

- Initiating element for requesting the release of electrical locking element in order to exit;

- Electrical locking element for securing an exit door;

- Electrical controlling element for supplying, connecting and controlling;

- Electrical locking element and initiating element;

- Signalling elements

In addition these electrically controlled exit systems can include time delay and/or denied exit mode.

The EN 13637 standard applies to both emergency and panic risks and the correct system solution should be commensurate to the specific risk applicable. The performance requirements of this standard are intended to assure safe and effective escape through a doorway with a maximum of two operations to release the electrically controlled exit system. A risk assessment that takes account of the type and number of users must be undertaken to determine the correct system solution and be recorded as part of the fire safety design summary (FSDS) for the building. The FSDS is submitted to the LA verifier at the same time as the Completion Certificate for the Building Warrant in submitted.

In all cases it is essential that the escape function of the door is not compromised at any time while the building is occupied. In particular, any additional dead bolt locking used must still enable the exit device to comply with the release requirements of EN 13637.

If delayed egress devices are to be used, they must be designed such that after the agreed delay period, the door will automatically be released. In the case of genuine emergency, such as a fire alarm or power failure, the door must be released immediately.

Any electrically controlled locking systems should be installed in compliance with BS 7273-4, Code of practice for the operation of fire protection measures. Actuation of release mechanisms for doors. The standard applies to all aspects of the interface between these mechanisms and a fire detection and fire alarm system.

It is proposed to cite BS EN 13637 but noting no intention to replace references to BS EN 1125 or BS EN 179 in the Technical Handbooks. Any reference to electrically controlled exit systems to BS EN 13637 in the Technical Handbooks will be as a risk-based alternative approach and complement existing standards.

The Scottish Government will continue work to draft amended guidance on locking mechanisms in the handbooks.

Consultation Question 21

It is proposed to cite BS EN 13637. Do you in principle:

- Strongly agree

- Agree

- Neither agree nor disagree

- Disagree

- Strongly Disagree