Scottish Child Payment and the labour market

This publication presents Scottish Government analysis of how Scottish Child Payment interacts with the labour market in Scotland including how it impacts labour market decisions of its clients.

Labour Market Economic Theory

Marginal Effective Tax Rates

41. Marginal effective tax rates (METRs), also referred to as marginal deduction rates, reflect the net financial impact to an individual of earning more through paid work, by taking into account reductions to gross earnings from tax and knock-on effects to benefit income. METRs vary at different levels of earned income as different tax rates and other reductions come into effect. Increases to METRs are considered to reduce incentives to work and vice versa for decreases to METRs.

42. The law of diminishing marginal utility argues lower income households place more importance on an additional £1 of income than higher income households, since at higher incomes, that additional £1 of income represents an ever smaller proportionate increase to someone’s income, with diminishing impact on utility (satisfaction).

43. While METRs do not consider the income of individuals, due to diminishing marginal utility, a low METR, of for example 20% (20% of additional gross earnings is lost through tax and benefit impacts), could be expected to be an even larger draw for a low income household to earn more through paid work than the same METR for a higher income household. In general, higher income households can have higher METRs than lower income households due to progressively higher income tax rates as income rises.

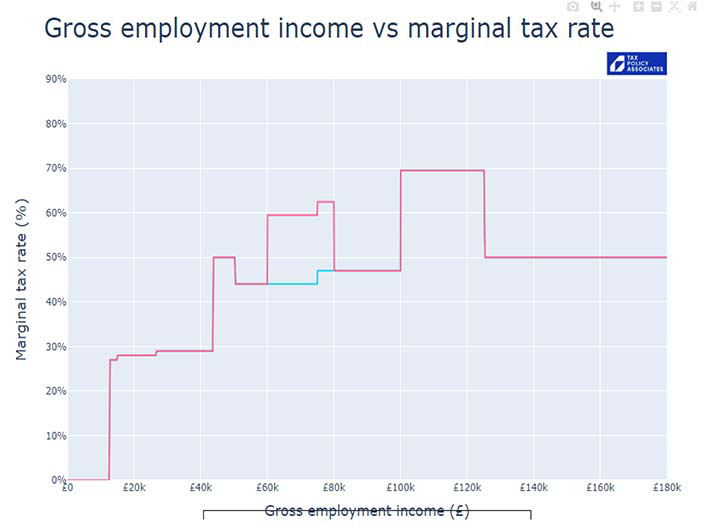

44. Figure 5 shows marginal tax rates for Scotland for 2024-25 with (red line) and without (blue line) the effect of the high income child benefit charge, applicable when annual taxable earnings reach £60,000 for an individual. This shows how METRs increase as employment income increases with particular pinch points when higher tax rates and benefit reductions and charges come into effect.

Source: Interactive marginal tax rate chart - June 2024 - Tax Policy Associates

45. In certain circumstances METRs can exceed 100%, and individuals can face a net financial loss of earning more through paid work. This can apply to SCP clients who are on the verge of earning above the limit where they would lose UC and their full SCP award.

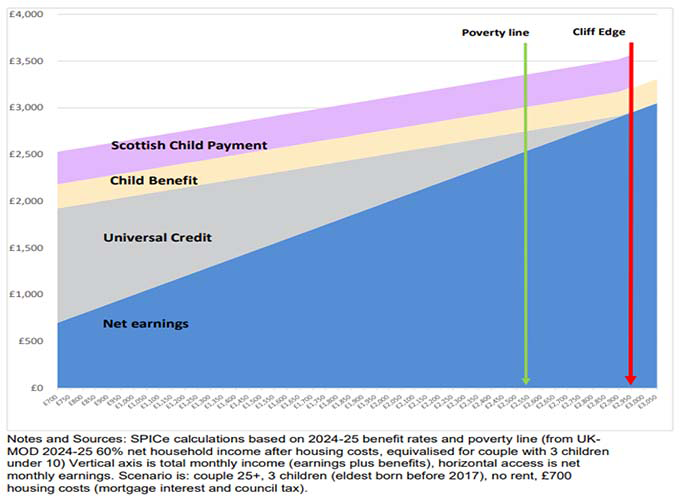

46. Analysis by SPICE sets out an illustrative example of how different forms of monthly benefit income changes with monthly net earnings for a couple household aged over 25 with three children in Scotland. This demonstrates how UC awards taper to zero as net earnings grow, with overall income increasing, but how SCP income remains constant until after the poverty line for this household type until it is no longer paid in its entirety[17]. It is at this “Cliff Edge” where a household’s METR would be particularly high and even when net earnings increase, overall income declines. See figure 6.

Source: SPICE briefing, Social Justice and Social Security Committee 16th meeting, May 2024.

47. METRs reflect the net financial effect of labour market decisions but are not a definitive guide to how labour market decisions are made. For example, METRs do not consider the opportunity cost of paid work. Opportunity costs in economics describes the loss of utility from alternative choices, specifically the next most optimal choice. For parents and carers with children and especially young children, the opportunity cost of working could be particularly high. Where they have a choice, parents of young children may place added importance on spending time with them at that young age rather than working, and this may wane as children grow older, although individual value judgements will come into play. Therefore METRs - which do not consider the opportunity costs of working - may be more representative for parents of older children than younger children.

48. Even where reductions in earned income do take place as a response to earning benefit income, these changes could have societal benefits and are not necessarily a net loss to the economy. There is an established body of research that highlights the limitations of typical economic metrics in representing certain types of work in the economy, primarily unpaid caring, often undertaken by women[18]. The assumption there is a net negative impact on the economy when a person moves from paid employment to spending more time with their children, implicitly undervalues that parent/carer and child interaction for both the parent/carer and the child.

49. Analysis[19] published by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation used Understanding Society data to estimate the carer pay penalty – defined as estimated foregone earnings from undertaking unpaid care – incurred by carers in the UK economy. This analysis estimates by the end of the sixth year, unpaid child-care givers (carers of children who are not sick or disabled) will have foregone a cumulative total of more than £100,000 in gross pay on average, while unpaid social-care givers (carers of someone who is sick, disabled or elderly) will have foregone over £30,000. These carer pay penalties are disproportionately experienced by women and households in poverty.

50. The ONS have developed an inclusive income methodology[20] as a new measure of economic progress to build upon existing measures such as Gross Domestic Product (GDP). GDP measures the market and non-market production and consumption of goods and services. However, GDP omits certain activities, such as unpaid household production of services, which might still be considered as economic activities and as activities that contribute to economic progress and well-being. Inclusive income expands the “production boundary” to include household production within its definition of economic activity giving greater prominence for human and natural capital, as well as non-market economic activity including household production.

51. In recognition of the importance of parents spending time with children at very young ages, maternity and paternity leave entitlement is a statutory right protected by legislation[21]. Parents could use the extra income from social security to spend more time with their child shortly after birth (Gonzalez, 2013)[22] and this has been shown to improve children’s cognitive development (Baum, 2003)[23]. There can be positive long run economic impacts associated with these types of effects, e.g. improved productivity in the economy[24].

52. Although there can be a short term loss to the economy from reduced labour market participation/supply of labour and its effect on reducing economic output and government revenues (e.g. PAYE receipts), this loss is exaggerated on the basis that unpaid care is typically not captured by traditional economic performance metrics. If this change enables people to use their time in a way that benefits them in the longer term, for example improving human capital though training for a job that more closely matches their skills, there can also be a net gain for the economy over the longer term. This could be amplified if this activity causes a change to an occupation that adds more value to the economy through higher wages, particularly if this is an occupation where there is currently a shortfall of supply – with potential benefits to business productivity.

Tapered benefit payments

53. Some stakeholders have recommended the Scottish Government consider tapering SCP awards to smooth cliff edge points where full SCP awards are lost[25]. This could operate in different ways. For example, it could operate similar to UC so that SCP awards reduce gradually as clients near the earnings threshold for their underlying benefit eligibility. The analysis set out here is an analytical discussion of hypothetical changes to SCP’s design and does not in any way reflect Scottish Government policy intent.

54. Eligibility for UC is based on income not working status[26] and if a client’s earnings are above their defined limit they lose eligibility for UC entirely. However, due to the UC taper rate (55%), as earnings near that threshold UC award amounts reduce gradually, so that every time a UC client earns more through paid work, there is still a net benefit even taking into account their reduced UC award (55p award reduction for every £1 of additional earned income). Only net earnings are taken into account for reductions to UC awards via the taper, after tax and other deductions have already been made.

55. UC taper rates also only begin when UC claiming households with children begin to earn more than their work allowance. If someone gets help with housing costs, their payment will start to reduce when monthly wages reach £404, equivalent to working around 8 hours per week at the national minimum wage (£11.44 if aged 21 or over). If someone does not get help with housing costs, their payment will start to reduce when monthly wages reach £673, equivalent to working around 14 hours per week at the national minimum wage.

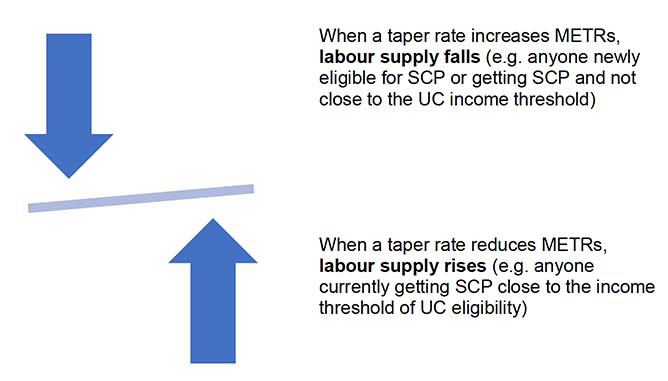

56. If an SCP taper rate moved in tandem with the UC award taper, it could increase work incentives for a small number of SCP clients at the margin of losing eligibility for UC who now have lower METRs and less concern of losing SCP awards entirely when earning more. Where a taper moves METRs from above 100% to below 100%, households now have a financial incentive to work more, as an increase in worked hours and earned income will now increase overall income, where it didn’t before.

57. Work incentives could improve for households where METRs fall and this should be most obvious for households around the margin of UC income thresholds, reflected by small UC awards. However, this is likely to affect only a small share of SCP clients. For UC awards for households with children aged under 16, around 2% of awards in February 2024 were under £100 a month, representing around 3,000 households. This would also represent around 2% of the households forecast to receive SCP in 2024-25.

58. However, a much large number of SCP clients would have higher METRs as taper rates are applicable where they weren’t before, and increases to earnings now result in reduced benefit income, with potential impacts on child poverty as benefit income previously paid at a flat rate, now reduces with earnings.

59. An SCP taper rate designed so that no current SCP clients experience lower awards would need to bring more households into SCP eligibility (since SCP eligibility and any taper would need to begin at income levels above current SCP eligibility – broadly above UC income thresholds) and this would increase Scottish Government expenditure on SCP, already at close to £0.5 billion.

60. It would also decrease work incentives for those households newly eligible who can now earn the same income as before by working less. Newly eligible households would also experience higher METRs at those earnings amounts where SCP is tapered, as even though overall income is now higher with the new inclusion of SCP, at the margin those households now lose a portion of benefit income when earning an additional £1 through work.

When a taper rate increases METRs, labour supply falls (e.g. anyone newly eligible for SCP or getting SCP and not close to the UC income threshold)

When a taper rate reduces METRs, labour supply rises (e.g. anyone currently getting SCP close to the income threshold of UC eligibility)

61. The opportunity cost of not working would also decline for any households newly eligible for a tapered SCP, making this option more financially attractive than before, as working less would now be partially compensated by a tapered SCP award, potentially reducing work incentives.

62. Introducing a taper rate to SCP would require changes to legislation and could require complex changes to Social Security Scotland payment systems to incorporate household earnings, income or UC data, potentially with high administration costs.

63. To determine whether a taper rate would provide value for money for the economy and taxpayer, the potential benefits of introducing a taper rate (e.g. any positive impacts on labour market outcomes or reduced expenditure on SCP) would need to be considered against the potential costs (e.g. increased costs for Social Security Scotland in implementing the payment, any societal cost (e.g. increase in poverty) of a reduction in income for benefit clients).

64. In summary, the current SCP award design of no taper concentrates high METRs for a small number of households close to the margin of eligibility where work disincentives may exist. Introducing a taper rate would reduce METRs for those people but would increase them for a much larger number of households and the expected overall net labour supply effect is unclear. A taper could also be very expensive and complex to introduce. Dependent on design, it could increase expenditure on SCP by widening eligibility or reduce awards for current clients, potentially with negative impacts on child poverty.

65. The following section presents analysis of UC data to explore what evidence currently exists about work disincentives for SCP clients, particularly for households close to the margin of SCP eligibility.

Contact

Email: Dominic.Mellan@gov.scot

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback