Scottish Crime and Justice Survey 2021/22: Main Findings

Main findings from the Scottish Crime and Justice Survey 2021/22.

9.1. Cyber crime in Scotland

What is cyber crime?

Cyber crime can be understood as either cyber-enabled or cyber-dependent crime.

Defining cyber crime is complex, with no agreed upon definition of the term. The main debate centres around the extent to which cyber technology[94] needs to be involved for the crime to be termed ‘cyber crime’.

For the purposes of the SCJS and the results in this section of the report, a broad definition of cyber crime is adopted that includes crimes in which cyber technology is in any way involved. This ranges from offences which would not be possible without the use of cyber technology, known as ‘cyber-dependent crimes’ (such as the spreading of computer viruses), to ‘traditional’ offences which can be facilitated by the use of cyber technology, known as ‘cyber-enabled’ crimes (such as online harassment).

How did the 2021/22 SCJS collect data about cyber crime in Scotland?

Internet users were asked about what types of cyber fraud and computer misuse they had experienced in the previous 12 months. Additionally, violent and property crimes which involved online activity or internet-enabled devices were marked with a ‘cyber flag’.

The SCJS asked respondents about their experiences of a range of different types of cyber fraud and computer misuse, which are listed below. These questions were asked for the first time in 2018/19 following a review and development of the questionnaire.

As this is only the third year these questions have been included in the survey, any changes between years should be treated with caution as no trend can be identified at this stage.

It is important to note that the findings from these questions are not included in the main SCJS crime estimates, and are not comparable with them. However, following extensive user consultation and questionnaire development, the questions presented here have been incorporated into a new victim form designed to estimate the prevalence of fraud and computer misuse victimisation in Scotland. More information on the background and next steps of this work is detailed in Annex D.

In terms of the findings presented here, only SCJS respondents who had accessed the internet in the 12 months prior to their interview were asked about their experiences of cyber fraud and computer misuse (91% of respondents).

Respondents were asked about what types (not how many individual incidents) of cyber fraud and computer misuse they had experienced in the previous 12 months while accessing their own internet-enabled devices (thus excluding, for example, workplace-owned devices). Up to three types of cyber fraud and computer misuse were recorded per individual and it is possible that certain crimes might relate to the same experience: for example, a specific incident could involve both a scam email and a virus.

Furthermore, when collecting information about people’s experiences of cyber fraud and computer misuse, the survey does not seek to capture instances in which a crime was only attempted (for example, when a scam email was received but the person simply deleted it).

A ‘cyber flag’ question was also first added to the victim form section of the questionnaire in 2018/19. This is central to understanding what proportion of property and violent crime involved the internet, any type of online activity, or an internet-enabled device.

Finally, the SCJS also collects information about stalking and harassment, which may also include a cyber element, for example if taking place on a social media website, or via email.

Drawing on the data collected across the survey, this section of the report presents results from the 2021/22 SCJS on the extent to which cyber technology is involved in a wide range of offences in Scotland. It is divided into four main sections:

- fraud and computer misuse

- cyber elements in property and violent crime

- cyber elements in stalking and harassment

- widening the focus: How does wider analytical work complement the evidence provided by the SCJS on cyber crime?

It is important to note that the data presented in this section comes from the analysis of the SCJS results. Police Scotland also collect data about cyber crime. More information on the police’s recording of cyber crime can be found towards the end of this section.

Cyber fraud and computer misuse questions

Respondents were asked if any of the following had happened to them in the previous 12 months:

- had their personal details (e.g. their name, address, date of birth or National Insurance number) stolen online and used by someone else to open bank/credit accounts, get a loan, claim benefits, obtain passport/driving license etc., hereafter defined as “personal details stolen online”

- had their devices infected by a malicious software, such as a virus or other form of malware, hereafter defined as “virus”

- had their social media, email or other online account accessed by someone without their consent for fraudulent or malicious purposes, hereafter defined as “online account accessed for fraudulent purposes”

- were locked out of their computer, laptop or mobile device and asked to make a payment to have it unlocked (known as ransomware), hereafter defined as “ransomware”

- had their credit card, debit card or bank account details (e.g. account number, sort code) stolen online and used to make one or more payments, hereafter defined as “card/bank account details stolen online”

- received a scam email claiming to be from their bank or another organisation (e.g. HMRC), and they provided their bank details or made a payment as a result, hereafter defined as a “scam email”

- received a phone call or message from someone claiming there was a problem with their computer or mobile device, and let them access their device and/or paying them a fee, only to find out it was a scam, hereafter defined as “phone scam”

- were victim of online dating fraud (e.g. sending money to someone they had been chatting to, or were in a relationship with, online but then discovering that their dating profile was fake, or never heard from them again), hereafter defined as “online dating fraud”

Fraud and computer misuse

Fraud involves a person dishonestly and deliberately deceiving a victim for personal gain of property or money, or causing loss or risk of loss to another[95]. While ‘traditional’, face-to-face fraud persists, a large number of incidents of fraud have moved online in recent years, with new types of fraud having been developed which can only be carried out online, such as some types of email scams. On the other hand, computer misuse crimes always include the use of cyber technology, and are set out in the Computer Misuse Act 1990. They include offences such as the spread of malicious software.

Most types of cyber crime covered by the SCJS questions are types of fraud, with the exception of the questions relating to malware and ransomware, which are types of computer misuse.

This section first explores fraud and computer misuse in Scotland through the analysis of the newer cyber crime questions. It then explores fraud levels from another perspective, by presenting the analysis of the longer-standing questions in the SCJS about identity and card theft. While it may be reasonable to assume that a large proportion of identity and card theft happen online[96], the extent of cyber involvement is unknown in these latter questions.

How common were experiences of cyber fraud or computer misuse in 2021/22?

The 2021/22 SCJS found that the vast majority (83.6%) of internet users in Scotland did not experience cyber fraud or computer misuse in the 12 months prior to interview.

When asked about their experiences, one-in-six (16.1%) said they had experienced at least one type of cyber fraud or computer misuse in 2021/22[97]. This is an increase from 13.9% in 2019/20 but down from 20.4% in 2018/19.

In 2021/22, under one-in-twenty (4.4%) internet users experienced more than one type[98].

As this is only the third year these questions have been included in the survey any changes between years should be treated with caution as no trend can be identified.

For context, the Crime Survey for England and Wales (CSEW) estimates that 6.5% of adults were victims of fraud and that 1.3% were victims of computer misuse in the year ending December 2022[99]. However, the CSEW and SCJS data are not directly comparable, as the two surveys ask notably different questions and follow different processes.

For example, the CSEW captures detailed information about specific incidents, which enables them to be examined by specially trained coders and recorded as a crime in a similar way to how other crimes are recorded by each survey.

In contrast, the cyber fraud and computer misuse questions in the SCJS are newer and designed to provide relatively high level and indicative information about the extent of reported victimisation in order to start building up evidence on cyber crime in Scotland (they do not include detailed follow up questions). This means that, for example, some incidents might be included where only an attempt was made, where it involved a workplace-owned device or where the incident occurred prior to the 12 month period asked about.

Which types of cyber fraud and computer misuse were most common?

In 2021/22, the types of cyber fraud and computer misuse that people were most likely to have experienced were receiving a scam email and providing bank details or making a payment, and having card or bank details stolen online.

The 2021/22 SCJS found that just under one-in-twenty people received a scam email and provided bank details or made a payment (experienced by 4.9% of internet users), and 4.4% of internet users experienced having card or bank details stolen online.

Figure 9.1 shows the proportion of people experiencing each type of cyber fraud and computer misuse. Overall, when combining categories into fraud or computer misuse[100], online fraud was a more common occurrence than computer misuse offences.

Figure 9.1: The most common form of computer misuse experienced virus, and the most common form of cyber fraud was receiving a scam email.

Base: All internet users (4,830) Variable: CYBER2.

How did experiences of cyber fraud and computer misuse vary amongst the population?

The 2021/22 survey found there was no difference in the overall likelihood of experiencing cyber fraud and computer misuse between males and females. However, when looking at individual types, males were more likely to have experienced a device being infected by malicious software (4.2% compared to 2.9%, respectively), and males were more likely to have been the victim of online dating fraud (0.5% compared to 0.1%, respectively).

Overall, variation in the likelihood of being a victim of any type of cyber fraud or computer misuse with age did not show a clear pattern in 2021/22. This is similar to findings in 2019/20 but contrasts 2018/19 where the SCJS found that those aged 60 and over were least likely to experience cyber fraud and computer misuse. As previously noted, it's not recommended to make definitive assessments regarding trends over time since these questions were initially introduced in 2018/19.

When looking at specific types of cyber fraud and computer misuse, the 2021/22 SCJS found that for instances where someone accessed social media, email or another online account for fraudulent purposes, those aged 60 and over were less likely to have experienced this than those aged 16-24 and 45-59 (2.5% compared to 7.2% and 4.4%, respectively).

The 2021/22 SCJS found no difference in experiences of cyber fraud or computer misuse overall by area deprivation, or between those living in urban and rural areas.

Area deprivation and rurality were not found to impact on the likelihood of becoming a victim of cyber fraud or computer misuse overall. However, internet users in urban areas were more likely to have experienced an incident where someone accessed an online account for fraudulent purposes than those living in rural areas (4.3% compared to 2.7%, respectively).

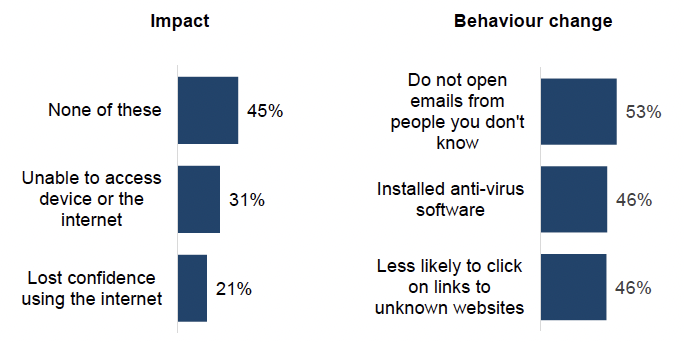

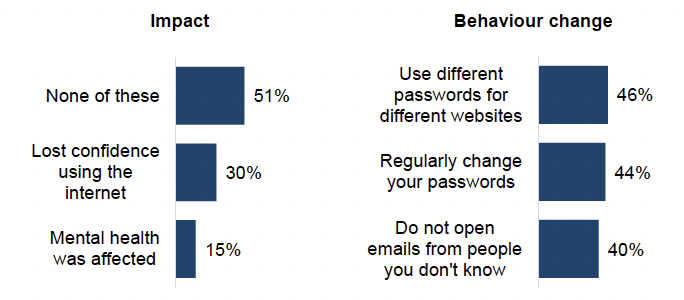

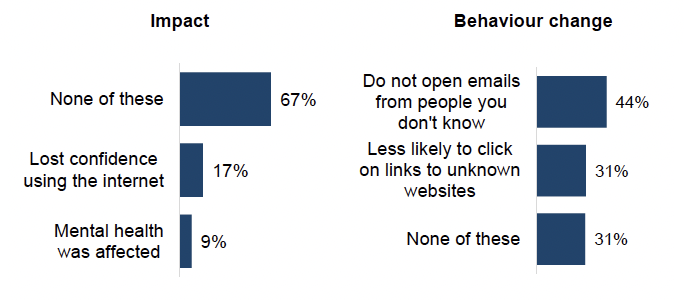

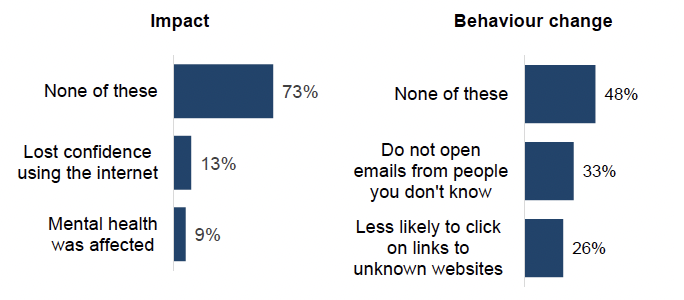

What impact did cyber fraud and computer misuse have on victims, and how did these experiences affect their online behaviours?

Victims were asked about the impact of their experience of cyber fraud and computer misuse crime, and whether the incident led to them modifying their online behaviours.

Respondents were presented with a list of possible impacts and behaviour changes, and were able to choose more than one option. These impacts and behaviour changes are listed below. This section presents figures for each type of cyber fraud and computer misuse individually[101].

The survey found that in 2021/22 a large proportion of cyber fraud and computer misuse victims said their experience had no impact on them[102] (73% of scam phone call victims; 67% of scam email victims; 51% of people who had their online account accessed for fraudulent purposes; 45% of virus victims). The most notable outlier was in the case of people who had their card or bank account stolen online, with the majority (70%) saying that the incident led to them losing their money, but that they were able to get it back in full.

The survey also found that the vast majority of cyber fraud and computer misuse victims said their experience caused them to change at least one behaviour (89% of people who had their online account accessed for fraudulent purposes; 87% of virus victims; 78% of people who had their card or bank account details stolen online; 67% of scam email victims).

Figure 9.2 presents commonly reported impacts for each type of cyber fraud and computer misuse, alongside commonly reported behaviour changes. The results for the full list of reported impact and behaviour changes (listed below) can be found in the online data tables.

Impact of cyber fraud and computer misuse:

- you lost money, which you did not get back or did not get back in full

- you lost money, but you were able to get it back in full

- you were unable to access your computer, laptop, mobile device, or the internet

- your mental health was affected (e.g. anxiety, depression etc.)

- you lost confidence in going online/using the internet

- other (specify)

- none of these

Behaviour changes as a result of cyber fraud and computer misuse:

- less likely to buy goods online

- only buy goods from websites with the padlock symbol

- less likely to bank online

- less likely to give personal information on websites generally

- only visit websites you know and trust

- only use your own computer/mobile device to access the internet

- installed anti-virus software

- automatically update systems and software when prompted to do so

- more likely to back up data

- less likely to click on links to unknown websites (e.g. in adverts, emails etc.)

- less likely to share/send links to friends etc.

- do not open emails from people you don’t know

- use different passwords for different websites

- regularly change your passwords

- took steps to learn more about online safety

- other (specify)

- none of these

Figure 9.2: Aside from card or bank account fraud, most often victims said the incident had no impact on them, but did lead them to change their behaviour.

Reported impact and behaviour changes following experience of cyber fraud and computer misuse.

Base: All victims of: virus (180); card or bank account details stolen online (210); someone accessed online account fraudulently (180); scam email (230); Scam phone call (160). Variables: CYBER3_2; CYBER3_3; CYBER3_5; CYBER3_6; CYBER3_7; CYBER4_2; CYBER4_3; CYBER4_5; CYBER4_6; CYBER4_7.

Did victims report cyber fraud and computer misuse and which authorities were the crimes reported to?

The majority of victims of most types of cyber fraud and computer misuse did not report the incident to the authorities. When the incident was reported, victims rarely turned to the police.

The SCJS also asked victims whether they reported the incident they experienced, and if they did, to whom[103]. If people had experienced more than one incident of a particular issue, they were asked to answer in relation to the most recent incident of that type of cyber fraud or computer misuse.

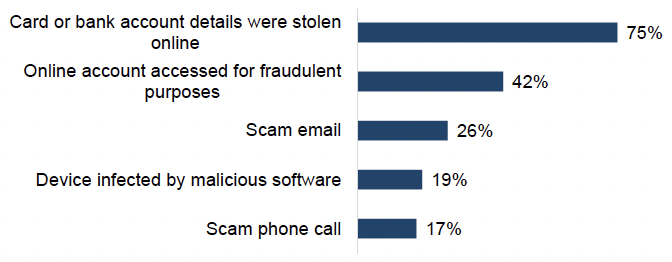

Overall, the majority of victims of most types of cyber fraud and computer misuse did not report the incident they experienced. The only type of cyber fraud and computer misuse which was reported by most victims was the online theft of a bank card or bank account details (reported by 75% of victims)[104].

Figure 9.3: The majority of victims of most types did not report the incident they experienced. The only type which was reported by most victims was the online theft of a bank card or bank account details.

Base: All victims of: card or bank account details stolen online (210); online account accessed for fraudulent purposes (180); scam email (230); virus (180); scam phone call (160). Variables: CYBER5_2; CYBER5_3; CYBER5_5; CYBER5_6; CYBER5_7.

Only a small proportion of victims reported the incidents to the police (6.6% of those having their card or bank account details stolen online, 4.2% of those who had an online account accessed for fraudulent purposes, 3.8% who experienced a virus, 2.1% who experienced a scam email and 1.8% a scam phone call.

A full breakdown of other authorities that victims reported incidents of cyber fraud and computer misuse to can be found in the online data tables.

Why did most victims of cyber fraud and computer misuse not report the incident to the police?

Many victims did not report cyber fraud or computer misuse to the police. A reason was that the incident was too trivial or not worth reporting (47% of people who had an account accessed for fraudulent purposes; 39% who experienced a virus; 37% who received a scam email; 36% who received a scam phone call).

Another common reason was that respondents dealt with the matter themselves (37% of people who experienced a virus; 35% who had an online account accessed for fraudulent purposes; 26% who received a scam email; 20% who received a scam phone call).

The most commonly cited reason for not reporting their card or bank account details being stolen to the police was that the victim thought that the incident would be reported to the police by the first authority[105] they had turned to (27%). This is in line with the finding that the majority (70%) of victims of card or bank account fraud who reported the incident turned to their bank.

A full list of the reasons why incidents were not reported to the police can be found in the data tables.

What else can the SCJS tell us about fraud in 2021/22?

Indicative findings suggest that just over one-in-twenty adults had their credit/bank card details stolen and around one-in-one-hundred had their identity stolen, however the extent of cyber involvement is unknown.

In addition to the cyber fraud and computer misuse questions, since 2008/09 the SCJS has captured evidence on people’s experiences of certain types of fraud, as well as their perceptions of fraud.

It is important to note that, unlike the cyber fraud and computer misuse questions, these are asked to all adults, not only to internet users. Furthermore, these questions provide indicative findings only, as respondents are not asked for full details of the incidents that would enable them to be coded into valid/invalid[106] SCJS crimes in the way that other ‘traditional’ SCJS crime incidents are. Nevertheless, the data remains valuable for time-series analysis purposes. It is reasonable to assume that a number of the fraud experiences being recorded by the SCJS have a cyber component, however, the extent to which this is the case is unknown. The 2023/24 questionnaire includes a new victim form which will allow for the prevalence of fraud and computer misuse in Scotland for the first time. More details on this and other future changes to the survey are provided in Annex D.

The SCJS found that 5.9% of adults in 2021/22 reported that they had their credit or bank card details used fraudulently in the previous 12 months. This is unchanged from 2019/20, and has increased from 3.6% in 2008/09. Identity theft was less common, with 1.0% of adults reporting experiences of such incidents in 2021/22, unchanged from both 2019/20 and 2008/09[107].

Although the findings from the SCJS are only indicative, it is notable that the CSEW finds relatively similar results on prevalence using a more expansive set of questions added in recent years to robustly capture experiences of fraud. The CSEW figures for the year ending December 2022[108] show incidents of fraud (excluding computer misuse) were experienced by 6.5% of adults in England and Wales.

What can the 2021/22 SCJS tell us about concerns about fraud?

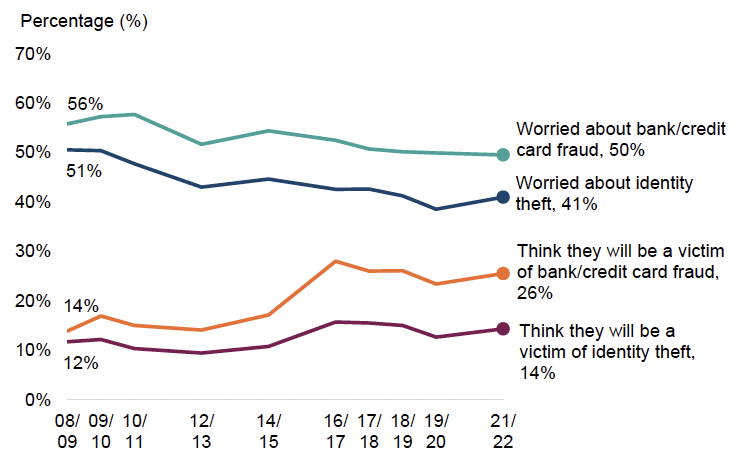

As in recent years, respondents in 2021/22 were most likely to report being worried about acts of fraud, as well as thinking these incidents were likely to happen to them in the next year, compared to other types of crime.

The SCJS also asks respondents which crime types they worry about happening, or think are likely to happen to them.

In 2021/22, half (50%) of adults in Scotland were worried about their bank/credit card details being used to obtain money, goods or services[109]. As in previous years, the next most worried about crime type was identity theft[110] with 41% of adults worrying about this issue in 2021/22. Levels of worry about these two types of fraud were higher than for all other crime types asked about in 2021/22. Looking over time, worry about both types of fraud has fallen since 2008/09. Worry about identity theft has slightly increased since 2019/20, up from 39% to 41% (worry about someone using their credit or bank details fraudulently has shown no change).

As in previous years, worry about both of these acts in 2021/22 varied by demographic characteristics. The SCJS found that females were more likely to be worried about fraud than males (54% of females worried about their credit or bank details being used fraudulently, compared to 44% of males, and 44% of females worried about identity theft, compared to 37% of males).

People between the ages of 16 and 24 were also less worried than all other age groups about having their identity stolen (16%) and about someone using their credit or bank details fraudulently (30%)[111].

People living in the 15% most deprived areas were less likely to be worried about credit fraud than those living in the rest of Scotland (45% compared to 50%, respectively). The same is true for worry about identity fraud (37% compared to 42%, respectively).

People living in urban areas were less likely to be worried about credit fraud than those living rural areas (49% compared to 52%, respectively). As with deprivation, the same is true for worry about identity fraud (40% compared to 45%, respectively).

In 2021/22, over half of respondents (57%) did not think it was likely that they would experience any of the crimes listed in the next 12 months[112]. However, the crime that respondents most commonly thought would happen to them was someone using their credit card/bank details fraudulently (26%). As with worry about crime, this was followed by people thinking their identity would be stolen (14%). The perceived likelihood of both credit card/bank details being used fraudulently, as well as identity theft, has increased since 2019/20 and since 2008/09. Worry and the perceived likelihood of experiencing a range of other crimes is discussed in more detail in Chapter 7.

While there was no difference in perceived likelihood of being a victim of identity theft between females and males, a higher proportion of females than males thought it was likely they would have their credit/bank details stolen (27% compared to 24%).

Age also played a role in defining people’s beliefs about the likelihood of being the target of fraud, with young people least likely to report thinking they would become a victim of identity theft (4%) or of card/bank account fraud (15%)[113]. In contrast, for those aged 45-59, one-in-five (20%) report thinking they would become a victim of identity theft, and one-in-three (33%) a victim of credit/bank account fraud.

Respondents living in the 15% most deprived areas of Scotland were less likely than respondents in the rest of Scotland to think that their credit/bank card details would be used to fraudulently buy goods/services (17% and 27%) and that their identity would be stolen (10% and 15%) in the next year.

Respondents living in urban areas were less likely to think that they would be the victim of credit card fraud compared to those living in rural areas (25% compared to 29%, respectively). There was no difference between these groups in the perceived likelihood of identity theft.

It is interesting to note that while the perceived likelihood of becoming a victim of fraud has increased over time, worry about fraud has decreased over the same period as shown in Figure 9.4. Please note that the extent to which people’s levels of concern for fraud related to cyber fraud incidents is unknown.

Figure 9.4: The perceived likelihood of experiencing fraud in the next year has increased since 2008/09, while worry about fraud has decreased since 2008/09.

Base: All adults 2008/09 (16,000); 2009/10 (16,040); 2010/11 (13,010); 2012/13 (QWORR identity theft: 12,010; card theft: 12,020; QHAPP: 12,050), 2014/15 (11,470); 2016/17 (5,570); 2017/18 (5,480); 2018/19 (5,540); 2019/20 (5,570); 2021/22 (5,520). Variables: QWORR; QHAPP.

To what extent did property and violent crimes have a cyber element in 2021/22?

In 2018/19, a ‘cyber flag’[114] was added to the survey questionnaire in order to enable the SCJS to examine the proportion of property and violent crime traditionally picked up by the survey with a cyber element[115].

The 2021/22 SCJS found that 3% of violent crime and 1% of property crime had a cyber element. The proportion of both violent crime and property crime with a cyber element is unchanged since 2019/20.

The SCJS also asks victims of violent crime whether the crime was recorded for instance on a mobile phone or camera, or by CCTV[116]. In 2021/22, 6% of violent crimes experienced by adults were recorded on a device, unchanged from the previous year.

Cyber elements in stalking and harassment

The SCJS asks respondents about their experiences of being stalked or harassed. Firstly, in the main survey a quarter of the whole sample are asked if they have been insulted, pestered or intimidated in any way by someone outwith their household in the year prior to interview. More detailed findings for the year 2021/22 are provided in the Focus on harassment and discrimination section.

Later, the whole sample is invited to complete the self-completion module on stalking and harassment[117], which asks respondents if they have experienced any of the following behaviours more than once: the receiving of unwanted letters or cards; receiving of unwanted messages by text, email, messenger or posts on social media sites; receiving unwanted phone calls; loitering outside their home or workplace; being followed; and/or having intimate pictures of them shared without consent, for example by text, on a website, or on a social media site[118]. Key findings on each of the self-completion topics from SCJS interviews conducted in 2018/19 and 2019/20 (described where relevant as 2019/20) can be found in the 2019/20 Main Findings Report. Supporting data tables have also been published to provide additional findings from these questionnaire sections. Due to improvements made to the partner abuse questionnaire for the 2023/24 survey sweep, analysts are currently developing plans on how to publish the findings for the standalone 2021/22 year. Further background to these changes are detailed in Annex D: Changes to the survey for 2023/24, and users will be informed of future plans through the ScotStat network.

To what extent were people insulted or harassed online in 2021/22?

The vast majority of adults (86%) did not experience being insulted, pestered, or intimidated in 2021/22, but among those who did encounter such behaviour, in-person experiences continued to be more common than online.

In 2021/22, 14% of adults said they had been insulted, pestered or intimated in any way by someone outwith their household. This was unchanged from 2019/20[119]. Of those adults that said they experienced harassment in the year prior to interview, the vast majority (80%) were insulted, pestered or intimidated ‘in person’, whilst 21% encountered such behaviour ‘in writing via text, email, messenger or posts on social media sites’[120] (unchanged from 2019/20[121]).

Widening the focus: How does wider analytical work complement the evidence provided by the SCJS on cyber crime?

A number of published strategies emphasise the challenges and risks of cyber crime, including the Strategic Framework for a Cyber Resilient Scotland, with an update of the progress made published in October 2023. Scotland’s Scams Prevention, Awareness & Enforcement Strategy is another document that has been produced by the Scottish Government, laying out a strategic framework to tackle scams in Scotland.

To inform this on-going strategic work, a range of analytical work is being carried outwith the aim of developing the evidence base around cyber crime. The sections below briefly highlight where the Crime Survey for England and Wales and Police Scotland’s cyber marker can tell us more about the involvement of cyber technology in sexual crimes, computer misuse and police recorded crime.

Computer misuse and fraud in the Crime Survey for England and Wales

As discussed previously, the Crime Survey for England and Wales (CSEW) has developed and included a substantial module to robustly capture experiences of fraud and computer misuse since October 2015. The questions provide estimates on the incidence, prevalence and nature of these crimes and also the proportion of fraud and computer misuse incidents that are cyber related.

The CSEW estimates that in the year ending in March 2022, there were 4.5 million fraud offences in the Telephone-operated Crime Survey for England and Wales (TCSEW), a 25% increase compared with the CSEW year ending March 2020. Further, they estimate that 61% of fraud offences were cyber-enabled in the year ending March 2022, up from 53% in the year ending March 2020, suggesting that much of the increase in fraud offences was because of increases in cyber-related fraud.

The TCSEW estimated that there were 1.6 million incidents of computer misuse in the year ending March 2022, up 89% from the year ending March 2020. Additionally, it estimates that 3.1% of people were the victim of a computer misuse offence in the year ending March 2022, a figure which has doubled in two years (1.6% in the year ending March 2020)[122].

Police recorded cyber crime

Crimes recorded by the police provide a very valuable contribution to the evidence base on cyber crime in Scotland.

Since the introduction of cyber crime markers on crime recording systems in April 2016, Police Scotland has continued to develop its marking practices across other Police Scotland recording systems and databases. This activity is being undertaken by the Cybercrime Capability Programme under Police Scotland’s ‘Policing 2026 Strategy’. According to a Police Scotland report in 2020, the tagging, marking, and logging of cyber crime has risen significantly in April-December 2019/20 compared to the same period last year, mostly as a result of the “Tag it, Mark it, Log it” campaign launched in October 2018 with the aim of improving Police Scotland’s ability to identify occurrences of cyber crime. As this marker becomes fully embedded across Police Scotland systems, it should provide a valuable evidence source of police recorded crimes involving a cyber element.

Scottish government statisticians have conducted a number of studies based on samples of police recorded crimes to enhance the wider evidence base on cyber crime. The findings are published annually in the Recorded Crime in Scotland national statistics bulletin. In 2022-23, an estimated 14,890 cyber-crimes were recorded by the police in Scotland. This is similar to the estimated volume recorded for both 2020-21 and 2021-22 (14,860 and 14,280 respectively), but remains significantly above the pre-pandemic year of 2019-20 (with 7,710 cyber-crimes).

The findings estimate that at least 5% of crimes recorded by the police in Scotland in 2022-23 were cyber-crimes. This includes an estimated 26% of Sexual crimes, 8% of Crimes of dishonesty, 3% of Non-sexual crimes of violence and less than 1% of Damage and reckless behaviour.

Further statistical studies into specific crime types recorded by the police can also provide more information about cyber crime in Scotland.

Published in January 2023, a study into police recorded hate crimes estimated the number of hate crimes that were cyber enabled. It found that in 2020/21, 9% of hate crimes were cyber-enabled. Transgender aggravated hate crimes and disability aggravated hate crimes were most likely to be cyber-enabled (27% and 18%, respectively).

Additionally, Scottish Government analysts studied a sample of police recorded sexual crimes from 2013/14 and 2016/17 and included consideration of the influence of cyber technology on sexual crime in Scotland[123]. This research found that both the scale and nature of sexual crime has been impacted by cyber technology in Scotland in recent years. For example:

- the research estimated that a rise in cyber-enabled 'other sexual crimes' has contributed to around half of the growth in all police recorded sexual crimes in Scotland between 2013/14 and 2016/17

- it is estimated that the internet was used as a means to commit at least 20% of all sexual crimes recorded by the police in 2016/17

Contact

Email: scjs@gov.scot

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback