International Development Fund: non-communicable disease programme

This report responds to a commission by the Scottish Government to design a new international development health programme providing support to the governments of Malawi, Rwanda and Zambia with a focus on non-communicable diseases (NCDs).

Appraisal Case – Part 2

How is cost effectiveness for NCDs measured globally?

58. The WHO standard approach is to rank cost effectiveness of an intervention against the GDP of the country (Table 8). WHO state that:[95]

- Highly cost-effective if that the cost is less than GDP per capita

- Cost effective if between one- and three-times GDP per capita

- Not cost-effective if greater than three times GDP per capita.

59. WHO has provided an assessment of the most cost-effective best buys with regards to NCDs valued at under USD$100 (81.58 GBP)[96] per DALY averted in a LMIC. A summary of the main interventions is shown in Table 9.

| Country | GDP per capita (USD) | WHO Classification of very cost effective | WHO Classification of cost effective | WHO Classification of not cost effective |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Malawi | 634.8 | <634.8 | 634.8-1904.4 | >1904.4 |

| Rwanda | 822.3 | <822.3 | 822.3- 2466.9 | > 2466.9 |

| Zambia | 1137.3 | <1137.3 | 1137.3-3411.9 | >3411.9 |

Table 9: World Health Organisation ‘Best Buys’[97]

Risk factor or disease: Tobacco Use

Intervention:

Tax Increases

Plain/ standardised packaging

Smoke free workplaces and public spaces

Public awareness through mass media about harms

Ban on advertising, promotion and sponsoring

Risk factor or disease: Harmful Alcohol Use

Intervention:

Tax increases

Restricted access to retailed alcohol

Bans on advertising

Risk factor or disease: Unhealthy diet and physical inactivity

Intervention:

Reduce salt intake in food through:

- Product reformulation

- Low salt options

- Food labelling

- Campaigns

Public awareness through mass media about physical activity

Risk factor or disease: Cardiovascular disease and diabetes

Intervention:

Counselling and multidrug therapy including glycaemic and BP control for people with high risk of developing cardiovascular events

Risk factor or disease: Cancer

Intervention:

Vaccination against HPV

Screening and treatment of precancerous lesions to prevent cervical cancer.

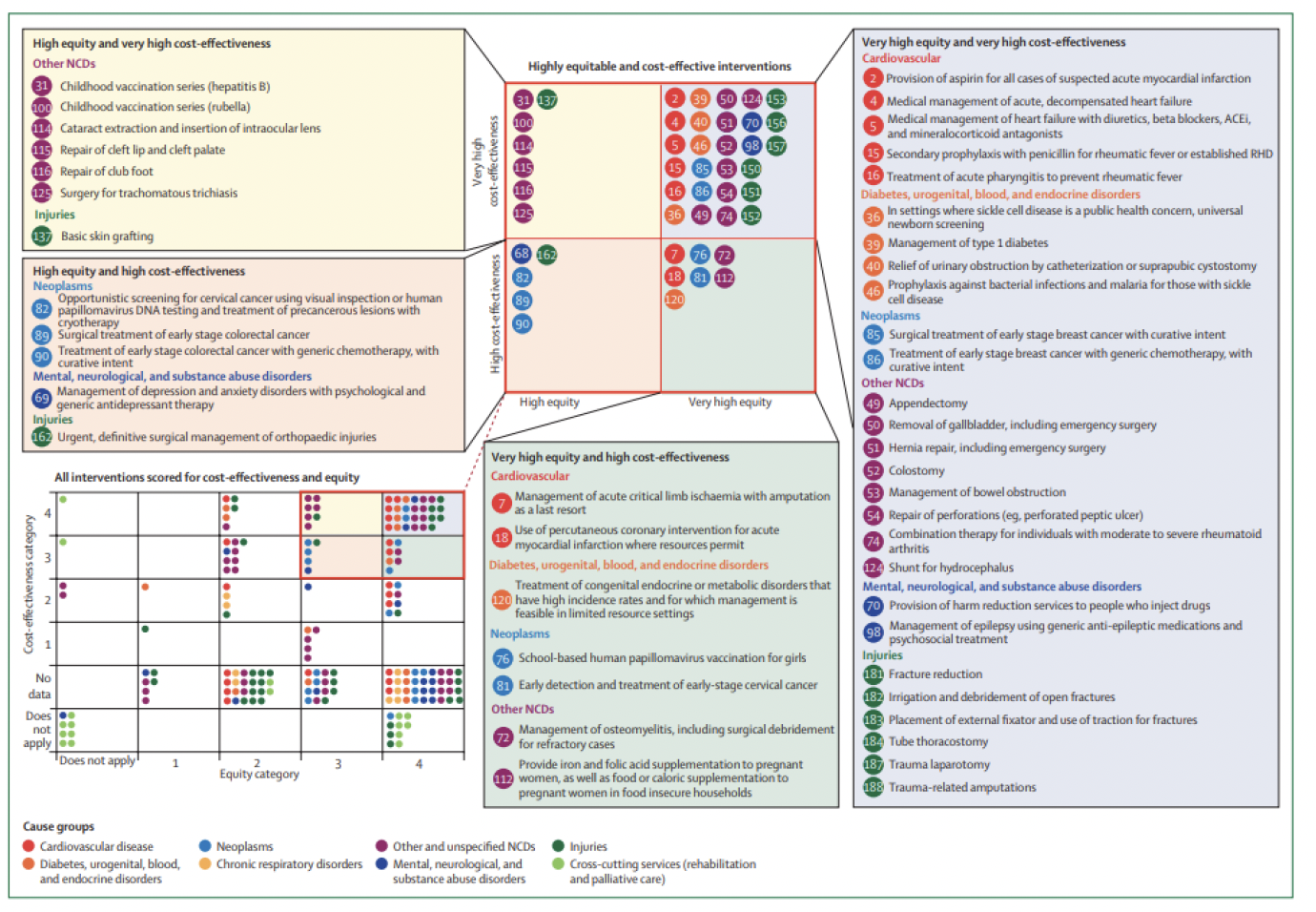

60. The Lancet Commission on NCDI Poverty scored a wide range of health sector interventions for cost effectiveness using systematic reviews, literature searches and consultation with the Global Health Cost-Effectiveness Analysis Registry ranking interventions on a scale of 1 to 4. For equity scoring a composite score was developed that incorporated concerns for priority to the poor, to women, to those with the least lifetime health and those with severe disabilities. This was validated using the DELPHI method. This method identified 27 health sector interventions for NCDs that were classed as highly cost effective and equitable (Figure 15).

How does the proposed SG programme compare to global NCD standards?

61. Table 10 compares the proposed SG programme against the Best Buys and the shortlisted interventions from the NCDI Poverty Commission.

Table 10: Comparison of proposed SG programme to Best Buys and NCDI Poverty Commission report

Components of SG programme: Global level

Summary: High level dialogue with likeminded partners; support for high level panels to disseminate and interrogate best practice and integration of NCDs into the UHC agenda.

WHO Best Buy overlap: Global advocacy on best buys including efforts to leverage finance and share learning

NCDI Commission overlap: Global advocacy on PEN Plus including efforts to leverage additional finance and share emerging evidence

Components of SG programme: Regional WHO

Summary: Support for WHO AFRO or the MPTF

WHO Best Buy overlap: Enabling environment for implementation of the best buys including hosting of workshops, technical assistance, high level meetings etc

NCDI Commission overlap: Support for WHO AFRO and specifically WHO Malawi, Rwanda and Zambia on NCDs and implementation of PEN Plus

Components of SG programme: Zambia Pen Plus training centre

Summary: Set up costs including curriculum development, training of trainers, provision of equipment or commodities, supervision,

secondment to MoH

WHO Best Buy overlap: Indirect increase in awareness of NCDs

Components of SG programme: Malawi Pen Plus scale-up

Summary: $84 (68.5 GBP) per capita

Infrastructure

Commodities

Training and supervision

WHO Best Buy overlap: Indirect increase in awareness of NCDs

NCDI Commission overlap: Medical management of heart failure

Prevention and management of Rheumatic Heart Failure

Newborn screening for and management of Sickle Cell Disease

Diagnosis and management of Type 1 diabetes and complications

Management of epilepsy

Components of SG programme: Rwanda integration of palliative care into PEN PLUS

WHO Best Buy overlap: n/a

NCDI Commission overlap: n/a

Components of SG programme: Peer to Peer

Summary: Includes for membership of PHS to IANPH99

WHO Best Buy overlap: Potential to work on all areas

NCDI Commission overlap: Potential to work on all areas

62. Table 10 shows alignment between the proposed SG programme and in particular the package of very cost effective and equitable services as identified by the NCDI Poverty Commission. The commission also proposes that complete coverage of the Essential UHC package will cost around USD$84 (68.5 GBP)[100] per capita, making it highly cost effective according to WHO definitions. This is akin to the package of services being delivered by the HSJF in Malawi. It also included start-up costs rolled in to give an average cost. NCD costs accounted for around 62% of the estimated cost in LICs and 70% in LLMICs.

63. They assumed that an increase in coverage of NCD interventions to 25% from a baseline of USD$2.5 (2.04 GBP)3 per capita would require an increase in spend per capita to USD$15 (12.2 GBP) in LICs.[101]

64. In terms of equity, PEN Plus improves access of the poorest to NCD diagnosis and care by explicitly ensuring a focus on NCDs not traditionally covered by global packages of care such as the WHO Best Buy series but that are of greater relevance to poorer and more vulnerable populations. In addition, Pen Plus moves care away from tertiary centres to district hospitals thus enabling some reduction in the distance patients need to travel to access care. However, in contrast to PEN which focuses on care at health centre level, support for PEN Plus assumes that services will be strengthened at health centre level in the medium to long term. In the interim barriers to accessing care and in particular long-term access to medication will need to be considered e.g. social protection measures to address travel costs, or OOPs or barriers to the long term cost of medication if not included in health insurance packages.

Limitations

65. Data on the cost effectiveness of PEN Plus is currently limited. As data emerges it will be easier to estimate the potential impact of the training and services in terms of DALY’s or quality-adjusted life years (QALY’s). In Zambia, funding of the training centre would take place alongside an existing research trial by the Zambian Government and University on PEN PLUS. The same applies for proposed plans to scale up Palliative Care in the community as part of PEN Plus in Rwanda. There is scope to work with the Rwandan Government to build the evidence base on this, depending on results. Malawi offers the opportunity to estimate incremental costs and coverage possible through integration of NCDs into a donor funded pooled fund that aims to support scale up of UHC. Once again SG funding could be used to add to the evidence base around this. Funding for palliative care and research into NCDs lags behind that of other areas of NCDs, so these components of the proposed programming offers an opportunity to the SG to shape the future evidence base.

66. Cost analysis of the political component is challenging. In the short term it is very difficult to measure the impact of dialogue or political engagement. In the medium to long term this might lead indirectly to a greater inclusion and financing of NCDs as part of the UHC agenda, but this would not be attributable to SG alone, and therefore difficult to measure.

What measures can be used to assess Value for Money for the intervention?

67. Economy: Are we buying inputs of the appropriate quality at the right price?

a) Unit cost of selected commodities (selected if they are high cost/high volume or price fluctuates)

b) Documented (total) savings on commodities (and other inputs)

c) Average unit cost per training per person trained

d) Unit cost per infrastructure units constructed/rehabilitated

68. Efficiency: How well are we converting inputs into outputs?

e) Unit cost per training centre or health facility supported

f) Joint funding with other donors through the HSJF means that the programme components can benefit from economies of scale and the absorption capacity of the HSJF will be monitored.

g) Funding directed to the point of use as well as the use of results-based incentives could further improve efficiency and result in better health outcomes than direct central funding only.

69. Effectiveness: How well are the outputs produced by an intervention having the intended effect?

h) Increased number of health workers trained

i) Number of health facilities able to deliver PEN Plus

j) Impact measures related to NCD mortality, NCD financing, training, following the main indicators in the log frame and related to the ToC.

70. Equity: How will benefits be distributed fairly/reach marginalised groups?

The approach to equity is based on supporting provision of services at a district level, rather than at a tertiary hospital level. Strengthening of a community-based decentralised health model with more focus on primary healthcare will improve equity by reaching the poorest and hardest to reach, particularly those in rural areas where minimal funds flow to from the centre. Indicative indicators include:

k) Availability of data on NCDs from district hospitals, including disaggregated data.

l) Advocacy for further WHO STEPwise approach to surveillance (STEPS) surveys and DHIS NCD components to understand service reach better.

m) Increased coverage and access to NCD services across more facilities.

n) Increased proportion of health workers outside urban centres able to deliver PEN Plus.

Summary Value for Money Statement for the preferred option

71. As noted, there is strong evidence to suggest that interventions to tackle NCDs are at an individual preventive level highly cost effective in comparison to WHO estimates. However, it is challenging to quantify the specific cost benefits associated with the proposed SG programme in part due to a lack of robust data on cost effectiveness of packages of care in LICs, and due to some of the interventions currently being considered pilots. SG intervention at political level has the potential to influence partner interests in NCDs, and to raise additional finance towards this largely neglected space. SG funding for regional and national programmes has the potential to add to the evidence base, building evidence of effectiveness.

Delivery modalities

72. SG has requested a model of delivery that limits the number of contracts issued. Assuming Option 3 as the preferred choice two delivery modalities are proposed for further consideration:

(a) Funding to one single agency that then channels support to the three countries:

i. Multi-Partner Trust Fund (MPTF): Funding is channelled to a financial instrument such as the MPTF. At present there are no large funding instruments set up to support delivery of NCD care. The MPTF has been set up to fill such a gap, with a focus on direct support to countries through the main UN partners working in this space: WHO, the World Bank, UNDP and UNICEF. Funding would be used to move forward policy development at national, regional and global level and to support direct delivery of priorities such as PEN Plus at country level. The MPTF would be required to provide reporting and oversight of the programme as required by SG. Discussions would be needed to understand whether the MPTF is able to deliver the programme as designed by SG including components on palliative care and also whether there are other like-minded development partners investing in the fund. In addition, it will be important to discuss and understand potential overhead costs which may be fixed.

ii. Independent fund manager identified through competitive tender: This would involve commissioning an overarching entity to oversee and manage the programme. Such an agency would be identified through competitive tender and would be required to oversee and monitor delivery of the different components of the programme design. The commissioned agency may be a private sector organisation, a UN body, an academic body or a civil society organisation. In terms of oversight and reporting, either SG could ask the fund manager for a point of contact e.g. the secondee into the Zambian MoH for Zambia and similar for the other two partner countries.

(b) Split funding into two separate LOTS. One LOT will focus on Malawi with direct channelling of funding to the HSJF with oversight, management and reporting provided by the Fund Manager. A second LOT would be awarded through competitive tender on support for scale up of PEN Plus in Zambia and integration of Palliative care into PEN Plus in Rwanda with similar arrangements for oversight, management and reporting.

73. Neither option includes work proposed at global level or the peer-to-peer learning component. Advantages and disadvantages of each modality have been listed Table 11.

Table 11: Advantages and disadvantages of different delivery modalities

Delivery modality: Funding to the MPTF to channel support to the three countries:

Advantages:

- Single contract making oversight and management less fragmented.

- Potential to ask that funds are targeted towards Malawi, Rwanda and Zambia.

- May allow SG the opportunity to lean into multilateral system and work with range of UN partners if the MPTF is chosen as the preferred delivery modality.

- Potential to influence other member states to join MPTF

Disadvantages:

- Relatively high overheads (likely >7%)

- Limited influence over spending decisions.

- Close scrutiny of spend beyond allocation to specific countries may be challenging.

- May not allow highly innovative approaches to be priorities e.g. integration of community palliative care into PEN Plus in Rwanda or channelling of funds into pooled instruments at country level

- Specific reporting to SG may be limited.

- Limit the ability of SG to support localisation agendas

Delivery modality: Independent entity identified through competitive tender (support for the HSJF in Malawi, support for the set up and running of training centres in Zambia and integration of palliative care into PEN Plus in Rwanda)

Advantages:

- Single contract making oversight and management less fragmented.

- Could include specific reporting arrangements for SG.

Disadvantages:

- Could be challenging to find an agency with the skills to deliver each of the different components whilst also being able to deliver on localisation/ decolonisation agendas etc.

- May be relatively high overheads with duplication of overheads in Malawi if funds are to be channelled to the pooled fund as recommended.

- May be challenging to direct funds to pooled funds such as in Malawi

- May limit SG influence at country level

Delivery modality: Split funding to two different entities

Advantages:

- Reduction in overheads fees for contribution to Malawi as oversight, reporting, and financial management done via the fund manager.

- Increased likelihood to find partner with research and implementation skills to share evidence from Zambia and Rwanda.

- Options to ask the secondee into the Zambian MoH to provide reporting to SG, and scope for a similar TA focal point identified in Rwanda.

Disadvantages:

- SG would need to engage directly in the programme in Malawi

Contact

Email: socialresearch@gov.scot

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback