The Scottish Health Survey 2023 - volume 1: main report

This report presents results for the Scottish Health Survey 2023, providing information on the health and factors relating to health of people living in Scotland.

2 General Health, Cardiovascular Conditions, CPR Training and Caring

Victoria Wilson

2.1 Introduction

Population measures of self-reported health have been found to be good assessments of past and future health, as well as predictors of illness recovery, declining functional ability, mortality, morbidity and/or use of health care. These measures can also reflect subjective lived experiences of diagnosed and undiagnosed physical and mental illnesses[31].

A growing proportion of the population in Scotland are living with one or several chronic health conditions that place increasing demands on health and social care provision as individual’s age and which affect the likelihood of being able to/remaining in work[32]. Further challenges are presented by continued inequalities in health outcomes and an ageing population[33]. Caring can impact the mental wellbeing and physical health of those fulfilling a caring role.

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is a general term for conditions that affect the heart and blood vessels. Its main components are ischaemic heart disease (IHD) and stroke, both of which are well-established clinical priorities for the Scottish Government[34],[35]. A key risk factor for CVD is hypertension (high blood pressure) where the additional pressure on the blood vessels, the heart and other organs can lead to chronic or even life-threatening conditions[36].

Diabetes, the most prevalent metabolic disorder, is a growing health challenge for Scotland. The majority of those registered as diabetic in Scotland have Type 2 diabetes, which can be influenced by demographic factors such as an ageing population and lifestyle factors such as diet, low levels of physical activity and obesity[37],[38]. CVD is closely associated with diabetes and the most common cause of morbidity and mortality amongst those with diabetes[39].

Over 3,000 people in Scotland have an Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest (OHCA), each year. The Scottish Government is part of the Save a Life for Scotland partnership which aims to increase the survival rate following an OHCA, by increasing readiness within the community to respond to such events through training and administration of Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (CPR)[40].

2.1.1 Policy background

The six Public Health Priorities for Scotland[41] are aimed at improving the health of people in Scotland and are supported by a number of strategies covering specific conditions such as heart disease, diabetes and stroke.

The Heart Disease Action Plan (2021)[42] sets out the priorities and actions Scottish Government will take to minimise preventable heart disease and ensure equitable and timely access to diagnosis, treatment, and care for people with suspected heart disease in Scotland. This includes detection, diagnosis and treatment of risk factors including hypertension.

Increasing survival following a cardiac arrest is supported by Scotland’s Out of hospital cardiac arrest: strategy 2021 to 202610. Key aims of the refreshed strategy are to equip a total of 1 million people in Scotland with CPR skills by 2026 and to increase the number of OHCAs which have a defibrillator applied before the ambulance service arrive from 8% to 20%.

A refreshed Stroke Improvement Plan, published in June 2023[43], sets out the Scottish Government’s vision for minimising preventable strokes and ensuring timely and equitable access to life-saving treatment. The Plan details a number of commitments relating to stroke care in Scotland, including prevention, acute treatment and post-stroke care.

In February 2021, the Scottish Government published the refresh of its Diabetes Improvement Plan[44] (DIP), which sets out aims and priorities to deliver safe and effective person-centred healthcare treatment and support. The Plan sets out priorities and commitments from 2021 to 2026 to improve the prevention, treatment and care for everyone in Scotland living with diabetes.

The Carers (Scotland) Act 2016 [45] took effect in 2018, extending carers’ rights to support[46]. The Scottish Government’s commitment to unpaid carers in Scotland is reflected in the National Carers Strategy[47] which sets out a cross-government approach to carers issues, including through social care, social security and supporting carers in employment and education through initiatives such as the Short Breaks Fund and the Carer Positive scheme[48].

2.1.2 Reporting on general health, cardiovascular conditions, CPR training and unpaid caring in the Scottish Health Survey

In this chapter, the following data are presented:

- self-assessed general health for adults and children

- self-reported CVD, diabetes, stroke prevalence and blood pressure levels for adults

- prevalence of self-reported long-term conditions for adults

- CPR training prevalence for adults

- unpaid caring prevalence and adult mental wellbeing (WEMWBS) scores by hours spent providing unpaid care per week

Figures are reported by age and sex.

For definitions of terminology used in this chapter and for further details on the data collection methods for self-assessed general health, CVD, diabetes, stroke, blood pressure, long-term conditions, CPR training and unpaid caring, please refer to Chapter 2, of the Scottish Health Survey 2023 volume 2 technical report.

Further breakdowns for long-term conditions, self-assessed general health, and caring indicators can be found in the Scottish Surveys Core Questions (SSCQ) - gov.scot (www.gov.scot), which asks harmonised questions across the three major Scottish Government household surveys.

2.1.3 Comparability with other UK statistics

The Health Survey for England [49], Health Survey Northern Ireland[50] and the National Survey for Wales[51] provide estimates of adults’ general health, long-term conditions, cardiovascular conditions and unpaid caring prevalence in the other UK countries. The surveys are conducted separately and have different sampling methodologies, so general health, cardiovascular conditions and unpaid caring prevalence estimates across the surveys are only partially comparable.

The 2021 censuses for England, Wales and Northern Ireland respectively[52],[53] collected data on self-assessed health and long-term conditions for both adults and children. The censuses were conducted separately and health estimates are only partially comparable with SHeS. The Scottish census was carried out a year after the other countries, in 2022, and this impacts comparability [54].

Data on CPR training is collected in the Health Survey for Northern Ireland[55] and the Wales Omnibus Survey [56]. The surveys are conducted separately and have different sampling methodologies so CPR training prevalence estimates across the surveys are only partially comparable. There is no comparable data collected in England.

2.2 Results

Summary points

In 2023:

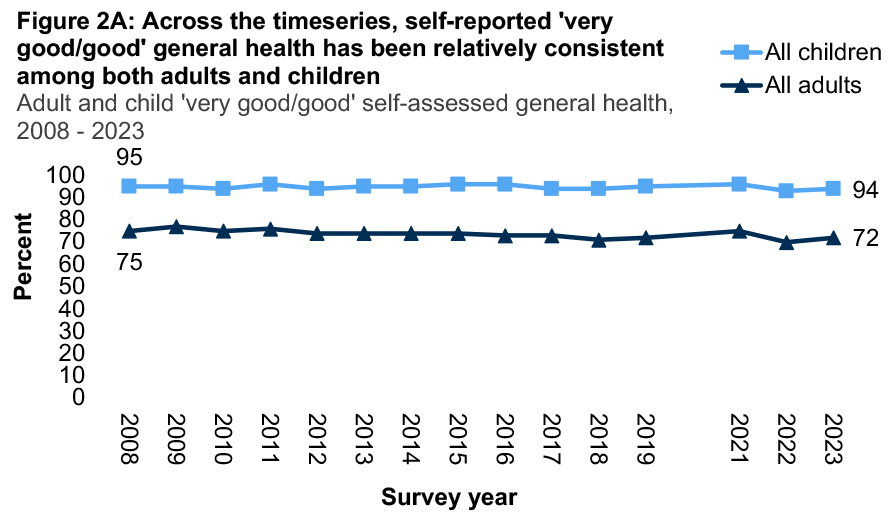

- Around three in four adults reported their general health to be ‘very good/good’ (72%), a figure at the lower end of the range recorded since 2008 (70% - 77%). The vast majority of children continued to report ‘very good/good’ general health (94%), similar to previous years (93% - 96%).

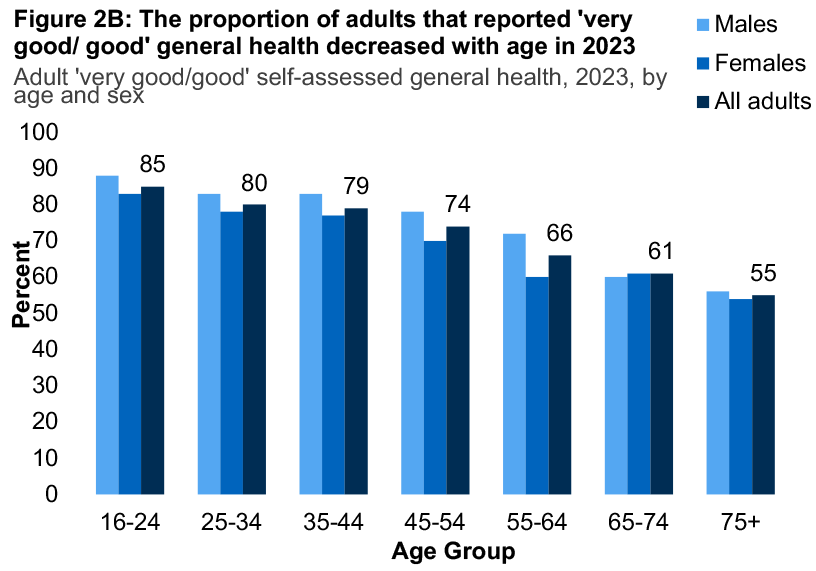

- The prevalence of self-reported very good/good health in adults decreased with age, from 85% among those aged 16-24 to 55% among those aged 75 and over.

- Adult prevalence of limiting long-term conditions was 38%. Females were more likely to report living with a limiting long-term condition than males (43% and 32% respectively), with the largest difference seen for those aged 45-54 (45% and 29% respectively).

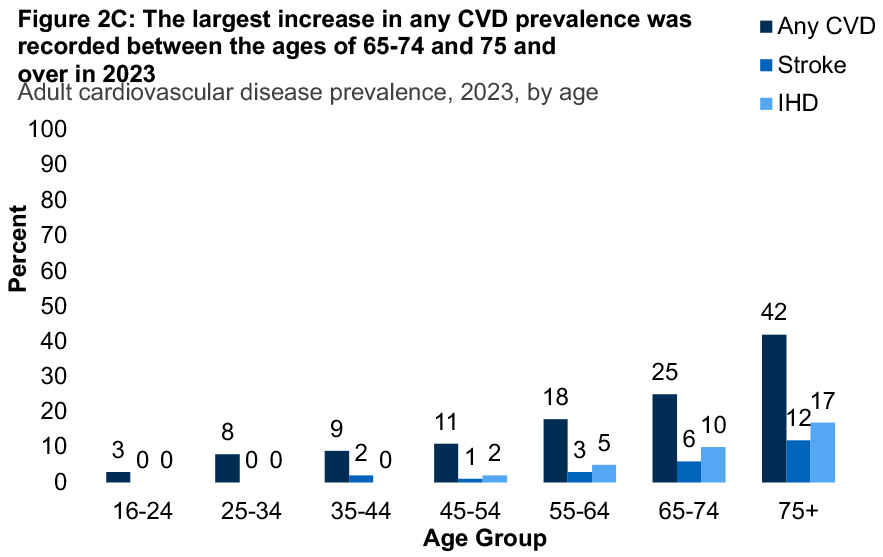

- Prevalence of any CVD (excluding diabetes or high blood pressure) remained at 15% of adults. As in previous years, prevalence increased with age from 3% among aged 16-24 to 42% among those aged 75 and over.

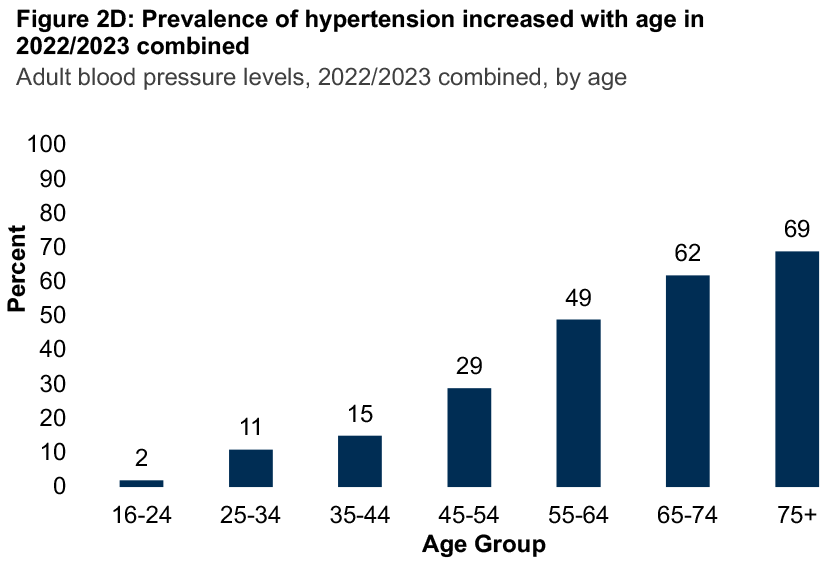

- In 2022/2023 combined, around one in three adults were recorded as having hypertension (31%), a similar proportion to that recorded in previous years (28% - 33%).

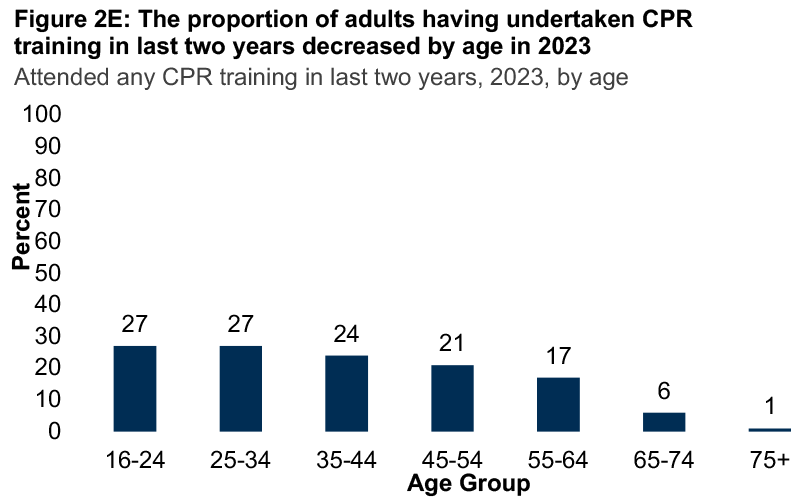

- More than one in two adults (57%) reported having ever undertaken CPR training and one in five adults (18%) had undertaken CPR training in the last two years.

- In 2023, 14% of all adults reported being unpaid carers, a proportion which was higher among females (16%) compared with males (11%).

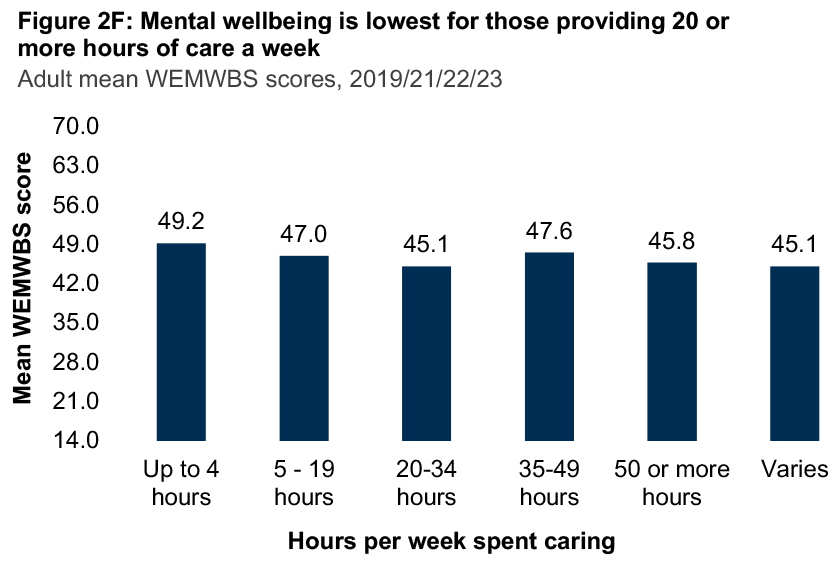

- Among unpaid carers, mental wellbeing was in the range 45.1 – 47.6 among those providing five or more hours unpaid care per week.

2.2.1 Since 2008, the proportion of adults and children reporting ‘very good/good’ general health has remained relatively consistent

In 2023, the proportion of adults who self-reported their general health to be ‘very good/good’ was 72%, remaining in the range seen since 2008 (70% - 77%). Self-reported health was higher among males (76%) than females (69%).

As in previous years, the vast majority of children were reported to have ‘very good/good’ health in 2023 (94%). This figure has been broadly consistent over the time series, in the range 93% - 96% since 2008.

2.2.2 Prevalence of self-reported very good/good health in adults decreased with age in 2023

The proportion of adults who reported their health to be ‘very good/good’ in 2023 decreased from 85% among those aged 16-24 to 55% among those aged 75 and over. Similar patterns were recorded for both males and females.

2.2.3 Females were more likely to report living with a limiting long-term condition than men, particularly those aged 45-54

In 2023, the prevalence of a limiting long-term condition among adults increased with age, from 24% among those aged 16-24 to 59% among those aged 75 and over.

A higher proportion of females reported living with a limiting long-term condition compared with males (43% and 32% respectively). The largest difference was recorded among females aged 45-54 compared with males of the same age (45% and 29% respectively). Table 2.3

2.2.4 Prevalence of any CVD and doctor-diagnosed diabetes have remained relatively stable since 2003

In 2023, 15% of adults reported living with any CVD, a figure that remained within the 14% - 16% range recorded since 2003. The prevalence of doctor-diagnosed diabetes remained at 7%, similar to levels in recent years and an increase from 4% in 2003 while prevalence of any IHD or stroke has remained in the range 7% - 9% (7% in 2023). Table 2.4

2.2.5 Higher prevalence of cardiovascular conditions was recorded among those aged 75 and over compared to younger age groups

As in previous years, the prevalence of any CVD (excluding diabetes or high blood pressure) among adults increased with age in 2023 from 3% among those aged 16-24 to 42% among those aged 75 and over. The largest increase was recorded between those aged 65-74 (25%) and those aged 75 and over, with a seventeen percentage point gap.

A similar, although less pronounced, pattern was recorded for the prevalence of doctor-diagnosed diabetes, which increased from 1% among adults aged 16-24 to 16% among those aged 75 and over. Type two diabetes remained more prevalent than type one among adults aged 35 and over, with an increase from 2% among those aged 35-44 to 14% among those aged 75 and over.

In 2023, the prevalence of IHD and stroke was highest among adults aged 75 and over (17% and 12% respectively).

2.2.6 The proportion of adults with hypertension has remained broadly consistent across the timeseries

In order to analyse data across the timeseries, nurse data or nurse-equivalent calibrated estimates have been used in this for this subsection.

Around three in ten adults in 2022/2023 combined were recorded as having hypertension (31%), a similar proportion to that recorded in previous years (28% - 33%). The proportion of adults where untreated hypertension was recorded was 19%, the highest figure recorded since 2003 (also 19%).

Similar patterns were recorded by sex across the timeseries. Table 2.6

2.2.7 In 2022/2023 combined, hypertension increased with age

Due to similarities in the proportions reported using the nurse-equivalent calibrated estimates and interviewer measurements, the latter is referenced in this analysis.

Older adults were most likely to record having hypertension in 2022/2023 combined (69% among those aged 75 and over and 62% among those aged 65-74). The largest increase in prevalence was recorded between adults aged 45-54 (29%) and those aged 55-64 (49%).

2.2.8 More than one in two adults reported having ever undertaken CPR training

Over half of adults in 2023 reported having ever undertaken any CPR training (57%). Those aged 65-74 (49%) and 75 and over (33%) were less likely to have ever participated in CPR training compared with 57%-64% of those aged 16-64.

Almost two in ten adults (18%) had undertaken CPR training in the last two years. This proportion varied by age, decreasing from 27% among 16-24 year olds to 1% of those aged 75 and over.

2.2.9 Adults aged 45-54 and 55-64 were most likely to report being unpaid carers in 2023

In 2023, 14% of all adults reported being unpaid carers, a proportion which was higher among females (16%) than males (11%). The proportion of unpaid carers was also highest among adults aged 45-54 (19%) and those aged 55-64 (21%). Table 2.9

2.2.10 Among unpaid carers, mental wellbeing was lowest among those providing five or more hours of unpaid care week

In 2019/2021/2022/2023 combined, variation in mental wellbeing, measured using WEMWBS mean scores, was evident according to the number of hours adults spent caring per week. Mean scores recorded among those who reported undertaking five or more hours of unpaid caring responsibilities per week were in the range 45.1 – 47.6, compared to 49.3 for those who provide up to 4 hours of care.

*Note: WEMWBS scores are calculated to fall in the range 14 to 70

Notes

- Some caution should be exercised when interpreting data for 2021 within any time series data presented due to some methodological changes during the pandemic. Please see the Scottish Health Survey 2022 - volume 2: technical report for more information.

- Blood pressure measurements were taken by an interviewer from 2012 onwards and converted to an equivalent of the nurse measure.

Table List

Table 2.1 Self-assessed general health, adults and children, 2008 to 2023, by sex

Table 2.2 Adult self-assessed general health, 2023, by age and sex

Table 2.3 Prevalence of long-term conditions in adults, 2023, by age and sex

Table 2.4 Cardiovascular disease and diabetes prevalence, 2003 to 2023, by sex

Table 2.5 Cardiovascular disease and diabetes prevalence, 2023, by age and sex

Table 2.6 Adult blood pressure levels, 2003 to 2022/2023 combined, by sex

Table 2.7 Adult blood pressure levels, 2022/2023 combined, by age and sex

Table 2.8 Adult prevalence of CPR training, length of time since original training and whether attended refresher, 2023, by age and sex

Table 2.9 Caring prevalence in adults, 2023, by age and sex

Table 2.10 Adult WEMWBS mean scores (age-standardised), 2019/2021/2022/2023 combined, by sex and hours spent each week providing help or unpaid care

References and footnotes

1 Balaj, M. (2022). Self-reported health and the social body. Social Theory and Health; 20: 71-89. [Online] Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/346184065_Self-reported_health_and_the_social_body

2 See https://www.gov.scot/policies/illnesses-and-long-term-conditions/

3 Scottish Government (2021). A Scotland For the Future: The opportunities and challenges of Scotland’s changing population. [Online]. Available at: https://www.gov.scot/publications/scotland-future-opportunities-challenges-scotlands-changing-population/documents/

4 Scottish Government (2021). Heart Disease Action Plan [Online]. Available at: Heart disease: action plan - gov.scot (www.gov.scot)

5 Scottish Government (2023). Stroke Improvement Plan 2023 [Online]. Available at: https://www.gov.scot/publications/stroke-improvement-plan-2023/pages/3/

6 See https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/high-blood-pressure-hypertension/

7 Scottish Government (2022). Type 2 Diabetes – framework for prevention, early detection and intervention: evaluation [Online]. Available at: https://www.gov.scot/publications/evaluation-implementation-framework-prevention-early-detection-intervention-type-2-diabetes/pages/3/

8 Scottish Diabetes Data Group, NHS Scotland (2023). Scottish Diabetes Survey 2022. [Online] Available at: https://www.diabetesinscotland.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/Scottish-Diabetes-Survey-2022.pdf

9 Leon, BM and Maddox, TM. (2015). Diabetes and cardiovascular disease: Epidemiology, biological mechanisms, treatment recommendations and future research. World Journal of Diabetes, Vol 6(13), pp. 1246-1258. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4600176/

10 Out of hospital cardiac arrest: strategy 2021 to 2026. Edinburgh: Scottish Government, 2021. Available at: https://www.gov.scot/publications/scotlands-out-hospital-cardiac-arrest-strategy-2021-2026/

11 Edinburgh: Scottish Government/COSLA (2018). Public Health Priorities for Scotland [Online]. Available at: https://www.gov.scot/publications/scotlands-public-health-priorities/pages/9/

12 Scottish Government (2021). Heart Disease Action Plan [Online]. Available at: https://www.gov.scot/publications/heart-disease-action-plan/

13 Scottish Government (2023). Stroke Improvement Plan 2023. Available at: https://www.gov.scot/binaries/content/documents/govscot/publications/strategy-plan/2023/06/stroke-improvement-plan-2023/documents/stroke-improvement-plan-2023/stroke-improvement-plan-2023/govscot%3Adocument/stroke-improvement-plan-2023.pdf

14 Scottish Government (2021). Diabetes care - Diabetes improvement plan: commitments - 2021 to 2026. Available at: https://www.gov.scot/publications/diabetes-improvement-plan-diabetes-care-scotland-commitments-2021-2026/

15 See: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/asp/2016/9/contents

16 See: https://www.gov.scot/publications/carers-charter/

17 Scottish Government (2022). National Carers Strategy [Online]. Available at: https://www.gov.scot/publications/national-carers-strategy

18 See: https://www.gov.scot/policies/social-care/unpaid-carers/

19 See: https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/health-survey-for-england

20 See: https://www.nisra.gov.uk/statistics/find-your-survey/health-survey-northern-ireland

21 See: https://www.gov.wales/national-survey-wales

22 See: https://www.ons.gov.uk/census

23 See: https://www.nisra.gov.uk/statistics/census

24 Scotland Census (2021). UK census data [online]. Available at: https://www.scotlandscensus.gov.uk/about/uk-census-data/

25 See: https://www.nisra.gov.uk/statistics/find-your-survey/health-survey-northern-ireland

Contact

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback