Scottish Mentoring and Leadership Programme: interim report - qualitative process and impact assessment

The Scottish Mentoring and Leadership Programme (SMLP) supports disadvantaged youth through MCR Pathways, a mentoring program improving education and life skills, and Columba 1400, which fosters leadership and confidence. The program has enhanced young people's wellbeing and outcomes.

Chapter 2: MCR Pathways

This chapter focuses on MCR Pathways and summarises the perceived reach, implementation and impact of the intervention on the young people taking part. It draws on the perspectives of pupils from two secondary schools who have taken part in the intervention, some of their parents or carers, mentors, the school staff involved, MCR staff, as well as the views of local authority and national stakeholder representatives.

Summary

- MCR Pathways was generally felt to be reaching young people in schools who would benefit most from it. Some local authority representatives mentioned that it is challenging for MCR Pathways to reach those care experienced young people who are most disengaged from school. As a school-based intervention, MCR Pathways cannot be expected to reach young people who are not at school – but this point highlights the additional disadvantage faced by this group of young people.

- The intervention was generally felt to have been implemented as intended. There had been some local changes to school Co-ordinator employment terms and the delivery of group work. These changes were intended to improve delivery in terms of reducing staff costs (and therefore increasing the sustainability of the scheme), and improving staff retention and intervention effectiveness for young people.

- Aspects of implementation that were seen to be working particularly well included:

- Co-ordinators introducing MCR Pathways to young people, which helped ensure it was communicated effectively

- MCR taking the lead on Co-ordinator and mentor recruitment, since it was reported that local authorities would struggle to find the resource for this and MCR have the experience and expertise to do this well.

- The main implementation challenge had been the salary cost of employing school Co-ordinators in a challenging financial environment for schools and local authorities, and in attracting and retaining the right staff to work on temporary contracts.

- Increased confidence was a dominant theme when discussing the key impacts of MCR Pathways on young people, particularly in relation to having increased social confidence and having more belief in their own abilities. Increased confidence also underpinned many of the other capabilities that pupils felt the scheme had improved, such as increased academic confidence, increased attainment/achievement and confidence in doing well at a job in future.

- There were also pupils for whom mentoring seemed to have made little difference, either because they perceived themselves to be doing well across the capabilities already or because they still appeared to be struggling with confidence and were not comfortable opening up to their mentor.

- Mentors were very positive about their experience of the scheme and highlighted that it had made a difference to their perceptions of young people, their own work and their own wellbeing. There were some suggestions for improvements to further support mentors, including: opportunities in the early stages to have a one-to-one conversation with an experienced mentor; greater signposting of peer resources; evening training sessions and more use of online breakout rooms; more information on what school is like for young people nowadays; where to find information to advise young people on post-school opportunities; and greater signposting of resources to help structure mentoring meetings.

- MCR was generally felt to have a positive working relationship with other programmes supporting young people, such as Developing the Young Workforce, Skills Development Scotland and the Promise, although there was a view that further work is needed to avoid duplication of effort in this space. There was also a desire for MCR Pathways to further enhance work experience and volunteering opportunities for young people.

- Parents who were interviewed were positive about their child taking part, however there was a desire for more information on the types of activities involved and a little more information on their child’s mentor.

- Other suggestions for improvement/good practice included: establishing formal end of year meetings between MCR and school staff to review the impact of the intervention; involving young people in Co-ordinator recruitment; ensuring Co-ordinators can access school IT systems; and mentors and mentees being able to meet outside school settings.

Co-ordinators being members of school staff so they were better able to raise awareness of the intervention and work closely with other staff members, so avoiding duplication of work already being done by Pupil Support Assistants. This was also felt to help Co-ordinators build relationships with pupils.

Overview of MCR Pathways

MCR Pathways is a school-based mentoring scheme that seeks to improve the life chances of care experienced young people. The overall aim of the intervention is to increase the number of young people in full-time work, college or university after leaving school (known as “positive destinations”). In doing so, the scheme aims to improve attainment, and staying on rates for S5 and S6 pupils, as well as support young people to develop key life skills. A more detailed overview of MCR Pathways is provided in Chapter 1. There was generally a good understanding of the aims of the intervention across the audiences interviewed for this research.

Are participants being reached as intended?

Overall, school staff and stakeholders felt MCR Pathways was reaching young people in schools who might benefit from taking part. Some local authority representatives mentioned that it is challenging for MCR Pathways, to reach those care experienced young people who are most disengaged from school. A school-based scheme such as MCR cannot be expected to reach young people who are not at school – but this point highlights the additional disadvantage faced by this group.

Identifying young people

School staff were responsible for identifying care experienced young people (Group One) and other young people who might benefit from taking part (Group Two). School staff gave examples of those in Group Two, including: young people who are impacted by parents with addiction issues; young people on the child protection register; young carers; young people with severe social anxiety; and young asylum seekers. Stakeholders highlighted the importance of school staff having the flexibility to decide which pupils take part, and trusting schools to make the right decisions.

School staff take a partnership approach to identifying young people. This involves discussions between the Co-ordinator, Pupil Support staff, class teachers and other relevant staff members. The Co-ordinator in one area also mentioned a partnership with a local third sector organisation supporting young carers. This organisation provides details of the young carers at the school and the Co-ordinator discusses with Pupil Support staff whether they would benefit from taking part. In some cases, the school may decide that the young person has “too much going on in their lives” or that the group dynamic would not suit them. However, their participation can be revisited in future. It is important to note that there is not a formal ‘referral’ system and young people have choice about whether not they engage.

School staff are able to identify care experienced young people through SEEMiS. However, one local authority representative noted that there may be Group Two young people, for example those with anxiety, who would benefit, but who have not been identified because they do not have a diagnosis or are not in touch with other sources of support. Participants also noted that school attendance is a barrier to taking part for some young people (discussed further below under Participation).

While all care experienced young people are eligible to take part, participants recognised that not all may need the intervention. An example was given of a care experienced young person who felt that they had enough support at home so did not need a mentor. Others talked about pupils who had some care experience when they were very young but have been settled with their family since then and were doing well.

There was general agreement that MCR Pathways should target these two broad groups of young people because they were the most likely to be disadvantaged.

Communication about MCR Pathways

One stakeholder was concerned that the scheme ‘singles out’ or ‘labels’ care experienced young people. However, school staff said they were careful to avoid stigma when introducing the scheme to young people. A Co-ordinator said they do not tell pupils why they have been put forward but instead say that Pupil Support thought they could benefit from extra support. This was reflected in conversations with pupils who often mentioned that they were not sure why they had been picked.

"I just got the letter and then I met [Co-ordinator] one day. I didn't know why I was doing it, I thought it was just random people that got picked". Pupil, S4, MCR

Pupils interviewed had generally heard about MCR Pathways in person from the Co-ordinator, Pupil Support staff or both. One Co-ordinator felt that it worked best for them to approach young people about taking part because they know most about the scheme so could explain it at an age-appropriate level.

“We know what our programme’s about - and guidance have their own idea of what the programme is and what it does, so they probably put it across more as the positive destination at the very, very end, whereas we want to start at the start and work through it all to get to that positive destination. You can’t just force that on someone when they can maybe be S1, S2.” Co-ordinator, MCR

Young people interviewed generally did not express an opinion about the process of being told about the scheme.

Parents/carers also receive information about MCR Pathways and must sign a consent form in order for young people to take part. One S2 parent felt they had enough initial information about the intervention and thought it would be beneficial for their child to take part. However, once their child had been taking part for some time, they said that they would have liked further information from the school on the types of activities involved. Another S4 parent commented that they trusted the school when they recommended mentoring but would have liked to have known more about the mentor who would be spending time with their child.

Participation

The MCR Pathways Impact Report May 2024 provides data on the characteristics of young people who took part in the academic year 2022/2023. This shows that:

- 39% of participants were care experienced

- Just over half of all participants (52%) were living in the most deprived areas of Scotland[12]

- The majority (61%) were registered for free school meals[13]

- Two-thirds (66%) had one or more additional support need.[14]

| Percentage young people taking part[15] | |

|---|---|

| Eligibility group | |

| Group One (care experienced) | 39 |

| Group Two (tough realities) | 61 |

| Deprivation | |

| SIMD 1 (most deprived) | 52 |

| SIMD 2 | 19 |

| SIMD 3 | 14 |

| SIMD 4 | 9 |

| SIMD 5 (least deprived) | 5 |

| Free school meal registration | |

| Registered for free school meals | 61 |

| Not registered for free school meals | 39 |

| Additional support needs | |

| One or more additional support need | 66 |

Young people interviewed described a variety of reasons for wanting to take part in the mentoring scheme. These included:

- For group work: a desire to make friends or because their friends were already attending; to take part in fun activities; or to develop skills.

- For mentoring: a hope that it would help with their anxiety and mental health; to replace another support activity that had come to an end (e.g. one young person attended groups outside of school to help with their anxiety but these were only available until S2); to have someone they can trust to talk to for advice; for help with school-work; or to help them work out what they wanted to do for a future career.

While some pupils wanted support explicitly related to positive destinations, such as helping them figure out what they wanted to do when they leave school, it was more common for pupils to want support with their wellbeing.

In terms of enablers to participation, young people mentioned that they were able to take part because the timings of the group work or mentoring worked around classes they did not want to miss. School staff observed that young people who had taken part in group work in S1 or S2 were more likely to take up mentoring when they were older. This was because they had developed a relationship with the Co-ordinator and so trusted them when they said that mentoring might be good for them. Young people interviewed enjoyed their mentoring or group work sessions; particular aspects they enjoyed are discussed later in this chapter.

School-based staff interviewed reported that there were no care experienced pupils in their schools who were missing out on MCR Pathways. However, one local authority representative felt that their local authority was not engaging as many care experienced young people as they had hoped. They highlighted that low attendance is a barrier to participation as young people need to be in school to benefit from group work and mentoring. This suggests that some of the most disadvantaged young people are less likely to be able to take part. Care experienced young people living in residential settings were also mentioned as having lower attendance. This local authority representative also said some young people do not see the benefit of taking part and/or are suspicious of another adult who wants to be involved in their life. They noted, however, that schools have been able to support young unaccompanied asylum seekers by MCR securing mentors who speak their language.

Another local authority representative also suggested that some school Co-ordinators in their area are less “embedded” within schools than others. They had encouraged schools to include Co-ordinators in regular Pupil Support team meetings, but this was not always happening. They felt that this impacted on how well staff were working together to identify young people and promote MCR Pathways.

In order to improve reach, one local authority representative mentioned working with MCR on engaging young people who are being educated in alternative provision, and had asked MCR to attend a meeting of their Corporate Parent Board to raise awareness of the scheme.

A school staff member commented that there is not enough support in schools in general – so there will always be more Group Two young people who could benefit. However, in their school, they felt that no care experienced young people were missing out.

Has MCR Pathways been implemented as intended?

Participants felt that MCR Pathways has generally been implemented as intended. However, initially, MCR and some local authorities had different expectations of how the scheme would be rolled out and there have been changes to fit the local context.

Schools usually become involved in the scheme after their local authority agrees to take part. Local authority representatives described their different approaches to deciding which schools in their area would sign up. For example, in one relatively small area, the local authority decided that it would only be fair if all schools took part (with school leadership approval). Another area left it up to headteachers to decide.

An MCR staff member commented that, while implementation needs to be cost effective for MCR, they try to adapt to local needs. For example, they had agreed to start the mentoring process early in one local authority because some schools felt that mentoring would help young people stay engaged in school. However, from the perspective of some local authorities, MCR was described as quite “rigid” in their approach to staffing. For example, one local authority wanted to begin with one or two schools before deciding on wider roll out. However, MCR had required that three or four schools take part to make delivery costs of a regional manager worthwhile for them (the local authority eventually agreed to this)[16].

A key change in intended delivery was around employment of school Co-ordinators. MCR had orginally expected that each school would have a dedicated full-time Co-ordinator, with their salary paid by the school or local authority. MCR believed that this is the best way to deliver on the aims of the intervention, and ensure its sustainability. However, this model was not always followed in practice. Not all schools felt they had enough care experienced pupils to justify a full-time Co-ordinator. For example, in one local authority, schools had initially employed full-time Co-ordinators but this was not financially viable in the long-term. One school had moved to a fixed-term, part-time contract which was seen as more cost effective for schools with a relatively small pupil roll. Local authority representatives did, however, highlight that fixed-term contracts are a barrier to hiring and retaining staff.

One local authority representative felt that MCR had only been willing to make compromises to school Co-ordinator employment when the local authority said they might pull out of the scheme.

“We had to enter into a discussion with MCR because they said that their model is a full-time person, and we said that that’s just not going to work for us. We’d said that we’re not the same as Glasgow. Our schools [don’t have] as big rolls. If you’ve got a school with a roll of 2,000, they have one person and our school had 400 so we felt it was different.” Local authority stakeholder, MCR

MCR now support part-time/flexible Co-ordinator roles.

Some stakeholders also commented on the cost for schools or local authorities of employing the Co-ordinators. They felt this was a barrier to more schools and local authorities taking part, which may impact on the future sustainability of the scheme.

What is working well, less well and what could be improved?

MCR support to schools with implementation

School staff and local authority representatives were positive about MCR’s support in the initial implementation stages and with recruitment of Co-ordinators and mentors. MCR staff were described as ‘lovely to work with’ and ‘happy to help’.

A local authority representative noted there had been turnover of MCR staff in their area which affected implementation, and that they had had to chase staff for data which they needed for local reporting.

School Co-ordinators

School Co-ordinators were felt to be key to the success of MCR Pathways. A local authority representative stressed the importance of having a staff member whose sole focus is on supporting the MCR cohort as opposed to Pupil Support staff who deliver universal support to a large cohort. A school staff member highlighted that having continuity of the same Co-ordinator helps them to become “established” in the school which supports information sharing between them and other staff and relationship building with pupils. Pupils were positive about how approachable and understanding their Co-ordinators were.

"She is like a big sister. You can just go and tell her anything. You know she is not going to be, like, 'oh, what', or anything like that. She will actually support you". Pupil, S2, MCR

As noted, schools appreciated MCR’s support with recruiting and training Co-ordinators. In terms of what works well with recruitment, one local authority had involved young people in interviewing candidates. They felt that this had helped identify candidates who were comfortable around young people. Another stakeholder suggested that it helps with delivery if Pupil Support Assistants move into Co-ordinator roles because they already know the school.

Mentors also highlighted the importance of Co-ordinators to the success of the intervention and in supporting them. They helped by being proactive in checking that meetings have been arranged, updating mentors on whether the young person is in school for their meeting, reminding them to complete feedback forms, and being responsive to questions.

"I felt I had the information to carry out the role successfully with the knowledge that [Co-ordinator] is hugely accessible, and very helpful, and if I need anything, I just send her a text and she tells me." Mentor, MCR

Some raised practical challenges relating to Co-ordinators being employed by local authorities but managed by MCR. For example, one local authority representative said that there can be difficulties with Co-ordinators accessing school systems. They had had to provide their Co-ordinators with a laptop so they could access training because their equipment (provided by MCR) was not compatible. (Note that MCR would now fund this.)

Group work

The first few group work sessions are about the pupils getting to know each other. The Co-ordinator then focuses on topics such as health and wellbeing, resilience, and team building.

Young people reported that they enjoyed the sessions. One young person said it was like “learning without knowing you are learning”. Specific aspects of the group sessions that young people liked included: being able to have music on in the background and choose what they listen to; spending time with friends; being able to speak to the Co-ordinator; the activities; and being asked what they would like to do in the sessions.

It was clear one reason for the success of the group work was the ‘non-judgmental’ space created by the Co-ordinator. This helped young people to open up during the sessions or feel they could speak to the Co-ordinator privately another time.

“We will talk about our feelings and how life at our house is going, and if there is anything wrong at our house, and if there is, then we can tell [the Co-ordinator], because we can all trust [her].” Pupil, S2, MCR

To improve the sessions, one Co-ordinator had made some changes to their groups. They said there were some quieter pupils who were not getting a chance to speak so they had split the S2 group into two smaller groups so the dynamic was better for them to be able to contribute.

MCR staff said that they have internal surveys which demonstrate the perceived impact[17] of group work on young people. However, not all stakeholders could see value in group work compared to mentoring. Some local authorities have stopped offering group work[18] or reduced this aspect of the scheme. One local authority representative was concerned that group work duplicated Pupil Support work already happening in schools and would like to see greater collaboration between Co-ordinators and other staff working with the same cohort of young people.

Mentoring

MCR is responsible for mentor recruitment and Co-ordinators are responsible for matching young people to a mentor. This was described as important because local authorities and schools would not have the capacity to take this on.

Participants described a thorough recruitment and matching process, which had helped young people and mentors to build a relationship. This was key to young people’s engagement. Young people and mentors answer questions about themselves, and the Co-ordinator matches them based on personality and interests. One mentor noted that they had learnt more about themselves from answering the questions. Stakeholders felt that there are relatively few matches that do not work out. Two young people interviewed had had a change in mentor because their original mentors’ circumstances had changed. These young people did not mind because they were happy with their new mentors.

Some mentors felt that it had taken a long time for them to be matched but they appreciated the school Co-ordinator reassuring them that they had not been forgotten, and were happy they had a good match in the end.

Some challenges were mentioned with mentor recruitment. In some areas, it was felt that recruitment takes a long time, which impacts on the number of young people who can take part. Particular challenges were mentioned for rural areas which have a smaller pool of volunteers to choose from, and where there are greater travel times for meetings. MCR was exploring whether it might be possible to offer some remote meetings in rural areas.

Mentors were generally positive about the quality of initial information, training and support. They highlighted the following aspects as working well: videos on the MCR website about the role of a mentor; training on adverse childhood experiences and active listening; being able to discuss case studies; and being provided with several opportunities to “pull out” of the process if they decided it was not for them.

A stakeholder mentioned that there have been changes to mentor training so it is less focused on statistics and more on case studies to show the impact of mentoring. There are also now more “focused” activities in the training sessions where mentors can discuss different scenarios.

Mentors did highlight some things that could be improved about the early stages. These included: an opportunity to have a one-to-one conversation with an experienced mentor; more use of breakout rooms in online training; training sessions in the evening so more people can attend; and information about what school is like for young people nowadays.

Pupils were generally very positive about their mentor. They described various positive qualities, such as being nice, patient, non-judgemental, and reliable – as shown in the following quotes. It was clear that having shared interests helped pupils to connect with their mentor and one young person also felt that because their mentor was relatively young, they could better relate to the issues they were facing.

“He doesn’t really rush you to talk. [He] lets you say what you need to say. He doesn’t say, ‘oh no, that's no right or something’…He is a nice guy, I really like him.” Pupil, S4, MCR

“They are very reliable, they come to most sessions. If they are sick, they can’t come, but they are very reliable. They are very nice, and you have a good time with them.” Pupil, S4, MCR

Young people generally did not have any suggestions for improvement about mentoring. However, some young people would like to be able to have mentoring meetings outside school (for example, in a fast-food restaurant) and suggested that they would feel freer to talk in that setting.

"It’s not really [mentor's] fault that we can’t really go outside of school premises, which is not the best, because I would like to go to [name of fast-food chain] or something, but you can’t really go outside school, which kind of limits the space that you can talk.” Pupil, S4, MCR

Some young people said mentoring was much more relaxed and informal than they thought it would be. Mentors typically said they let their mentee take the lead on what they want to discuss in the session. While there was a general appreciation of the importance of the process moving at a comfortable pace for the young person, some mentors found it challenging to know when to “push conversation” when young people are quiet. One mentor suggested that it would help to know more about the young person’s interests before meeting so they “don’t have to drag that information out of them.” However, others recognised the importance of the young person sharing what they are comfortable with. It was noted that “icebreaker” games were helpful in getting conversation going and that there could be more signposting of resources. For example, a mentor had used the Mentor Hub for ideas of activities for their meetings but felt this had been “glossed over in the training”.

Mentors also highlighted other areas where they would appreciate more support. One mentor was worried about child protection. They said that, although initial training on this had been helpful, and they could reach out to the school Co-ordinator for support, they still worried about it. This mentor would also appreciate more signposting of where to find information (e.g. on apprenticeships) and advice on how much time they should spend on researching things for their mentee outside mentoring meetings.

Mentors appreciated opportunities to connect with other mentors through organised events and informal meetings. However, not all mentors were aware of peer resources available or had been able to attend events. A mentor mentioned that they have informal conversations at school with other mentors while waiting for their mentee to arrive for their meeting. These informal conversations had reassured them that other mentors experience similar challenges.

In terms of practicalities, it helps mentors to schedule mentoring meetings in advance so they can block out time in their diary and communicate to colleagues that these meetings cannot be changed. It can be challenging to find meeting rooms in some schools. Some mentors found that it helped their mentee to meet in an open area like the library because meeting in a small room was “too intense”. There was also a suggestion that meeting in an open area is important for making mentoring more visible to others in the school, so it is not seen as “something to be hidden away”. However, another mentor had found that it was better to meet in a more private setting.

One mentor also noted that they would ideally have chosen a school closer to their home because the travel can be a challenge in winter. They chose a school further away because they were concerned about bumping into their mentee outside school.

To what extent has MCR Pathways supported the capabilities of young people?

Evidence in this section draws on the views of pupils, school staff, mentors, parents, and local authority representatives. The pupils were all currently participating in group work or mentoring. When interpreting these findings, bear in mind that the relatively small sample size means that the young people interviewed may not be representative of all pupils taking part or all care experienced pupils.

Among girls, in particular, increased confidence was the dominant theme when we asked about the overall impact of MCR Pathways. More specifically, this included feeling more confident in social situations, having more confidence in their own abilities, and having more confidence in dealing with bullies.

“I think she [mentor] has definitely been a great help in my self-confidence, which has only improved my social confidence”. Pupil, S4, MCR

"It made me more confident about [dealing with] bullying and stuff." Pupil, S4, MCR

"When I first met my mentee, she was quite introverted and all the conversation was coming from me. Now that's reversed, she's quite happy to tell me about what's she's done at the weekend and her social activities and her schoolwork and home life. So she takes the lead now which is really a big change." Mentor, MCR

This increase in confidence was attributed, in part, to encouragement from mentors and MCR Co-ordinators. These individuals were described as ‘patient’, ‘non-judgemental’, and ‘reliable’ which allowed them to build strong relationships with pupils. One pupil talked about having the confidence now to become a Young Carers Ambassador:

“[The MCR Co-ordinator] basically just cheered me on through it all and basically said, ‘you should definitely do this, I think you’d be good at it’." Pupil, S2, MCR

More broadly, having another person to talk to – who is independent from the young person’s family and the school and can give another perspective – was seen as one of the key benefits of having a mentor and one of the main ways in which they made a difference. This was mentioned in relation to increasing confidence but also to several other capabilities.

"I just chat more about how I’m feeling about stuff without having someone who’s involved in it as much as, like, my friend or my family members, or my teachers. " Pupil, S4, MCR

The mother of one pupil felt that the mentor provided the external validation her daughter needed to boost her confidence:

“I’m expecting you to say that I’m great and whatever. You’re a mum, of course you are. Of course you’re going to say those things. So, I think she, kind of, looked for maybe that validation and that belief elsewhere. I think the mentoring, the fact that it’s not school and it’s not home. Probably the biggest thing is that it is somebody who doesn’t know her history unless she’s told them her history". Parent, MCR

Other improvements which different pupils saw as having the most impact on them, personally, were:

- Feeling less anxious

- Improved attendance at school (in one case, this was due to feeling less anxious)

- Feeling calmer

- Feeling less angry

- Knowing more about what they wanted to do after school.

However, there were pupils for whom mentoring seemed to make little difference. One pupil indicated that he liked his mentor and enjoyed the sessions, but felt he was already “fine” in relation to most of the capabilities and his perspective was that the mentoring had made no difference.

Another pupil said that her mentor was “a nice person” but that MCR Pathways had made no difference to her. She was very quiet, lacked confidence and was clearly not comfortable talking to the researcher. Her mentor admitted that it had been very difficult trying to get her to open up:

“It's very difficult, it’s like drawing teeth. They don't know you from Adam, so they don't know what you're going to be like and so it's a slow, slow process of building up trust." Mentor, MCR

In this next section, we look at each of the ‘being’ and ‘doing’ capabilities in turn. As outlined in the introduction, we explored each capability with pupils and parents in the form of statements (see Appendix 3 for the list of statements and related capabilities). School staff, stakeholders and mentors were shown the logic model (see Appendix 1) and asked to pick out the capabilities where they felt the MCR Pathways had made the most difference and where it had made less of a difference.

Being capabilities

Increased academic confidence

There was considerable agreement that the MCR Pathways had helped young people to have more belief in their ability to do well in school and gain qualifications, but pupils often struggled to explain why that was. Some mentioned how mentors and MCR Co-ordinators had encouraged pupils to focus and not get distracted in class. Others gave specific studying advice:

“I was chatting about how, like, burnt out I get from studying and how I lose interest really quickly, and I can’t hold focus. And she was talking about how there’s, like, this way of studying where you do 20 minutes on, and then you take a 20 minute break, and then you do 20 minutes on, 20 minutes off. And then you do half an hour on, and then you finish for the day […] It actually really helped. I did that to pass my English prelim." Pupil, S4, MCR

“[my mentor] was like ‘over the holidays just try and focus on revising for your prelims, try and not go on social media as much', because that's a really bad habit of mine. 'Just try and focus on revising for your prelims, and I'm sure you will do great’." Pupil, S4, MCR

Increased social confidence

As noted above, confidence was one of the main areas that MCR Pathways helped improve. This was particularly mentioned by girls. In particular, feeling more comfortable speaking to other people, and feeling better about themselves, were commonly identified as areas where pupils felt the intervention had made an impact.

A teacher had observed young people being able to have ‘positive conversations’ with people around the school and navigating friendships better. He attributed this to the fact that the group sessions involve a good deal of work on confidence and communication.

Enhanced social capital

Having more people to talk to about things was also frequently identified by pupils as a positive impact of the scheme. They tended to cite their mentor, the MCR Co-ordinator and other pupils in their group sessions – but some also indicated that they had found it easier to talk to other people. One pupil mentioned a friend at college that he ‘can tell things that no-one else knows about’ and he thought this was because he had become used to opening up to his mentor. Another felt she could tell her friends more about herself:

“…it opens up a lot of my circle to be able to talk more openly about my passions. Things I have been shy about before, but with that support [from her mentor], I have been happier to share a lot of my interests and hopes for the future." Pupil, S4, MCR

Family relationships were an area where MCR Pathways appeared to have less impact, with none of the pupils citing it as a key impact – but neither did they indicate that this was something that they particularly wanted from the scheme. In a number of cases, young people and parents already felt the relationship was good.

Improved health and wellbeing

Feeling happier was one of the impacts most commonly selected by pupils. This resulted from a combination of factors including enjoying the group sessions/mentor sessions and feeling better afterwards.

"He is a nice person, he just makes me laugh, and I'm really happy." Pupil, S4, MCR

"There has definitely been an increase in my overall happiness, my overall enjoyment of school, knowing I have that at least once a week to come and see someone and speak about [my mental health struggles]." Pupil, S4, MCR

Improved relationships with peers was also mentioned as a reason for feeling happier (see ‘Improved relationships with peers’ below).

Feeling less anxious was an impact identified by a number of pupils. Talking over current worries and concerns with their mentor or MCR Co-ordinator helped with this. However, other pupils (and a couple of parents) said that feeling less anxious was something they wanted, but they were not sure how mentors could help.

“Well, I’m not too sure what my mentor could do about this. But it’s just something that I hope could happen, because oftentimes I am anxious about things in life.” Pupil, S4, MCR

Increased workplace knowledge and skills and higher aspirations

Pupils commonly felt that they knew more about the kinds of jobs they might like, were more confident about doing well at a job in the future, and were aiming higher in terms of what they wanted to do after school. This seemed to stem from mentors asking them about what they want to do and what their interests are – and providing encouragement to follow that path. Mentors also shared information about their own career paths and jobs they had done. Some pupils felt that they had been deliberately matched with a mentor in a job that fitted their own aspirations.

Doing capabilities

Improved relationships with peers, families and key adults

A number of pupils said that they had new friends, were getting on better with their friends, and/or were avoiding peers who caused problems. Pupils talked through friendship issues with their mentors who gave advice on how to sort out problems and encouraged them to spend time with friends who were more positive influences.

"I had quite a lot of friend problems, like, toxic friends. Friends that just talked about you behind your back and everything. […] I spoke to my mentor about it and she was, like, ‘well whoever has like just been backstabbing, just don't talk to them’. So, that's what I did. I started talking to the friends I am with now. I started hanging around with them more. […] So, I stopped hanging around the people that weren’t good in my life, and I started talking to them more, and now I'm with one of these every day of my life." Pupil, S4, MCR

"Before he would never speak to his friends on the phone, he would only ever text them and now he speaks to them a lot more on the phone. He's going out more with his friends rather than staying in the house." Parent, MCR

As noted above under ‘Enhanced social capital’, family relationships was an area where MCR Pathways appeared to have less impact. In a number of cases, this was because relationships were already good.

Relationships with teachers was another area where the intervention had less impact. Again, this was often because pupils felt they already got on well with teachers.

Stronger young person voice in schools

A number of pupils agreed that they felt more involved in school decisions. One pupil explained that this stemmed from her becoming more confident talking to other people – she had talked more in class and subsequently become class representative. Another felt it was due to the support she received from her mentor.

A couple of young people disagreed that the MCR Pathways had made a difference to their involvement in school decisions but said that it was something that they would like mentoring to help with.

There was a similar level of agreement among young people that they had been able to put some of the leadership skills that they had learnt as part of the scheme into practice at school. One boy talked about a form he had sent round the school to get backing for an issue he felt strongly about. Others felt that they had always shown leadership, to some extent, but mentoring had given them an extra boost.

Engagement in wider activities

Few pupils said that they were now doing more activities out of school and none identified that the scheme had made a key difference to this. Several pupils indicated that it had made no difference because they were already involved in a number of activities.

A parent was pleased that her son now went out to play football and had joined some after school clubs. She thought this was because the intervention had increased his confidence and resilience.

One of the mentors said that the young person she mentored was not necessarily doing more activities, but was exercising more choice in what she did; participating in the sports she was interested in rather than what her mother thought she should do. The mentor thought this was partly due to an increase in confidence but also just ‘growing up’.

Increased engagement in learning

In relation to staying on longer at school than they had originally planned, pupils commonly indicated that MCR had made no difference because they had always planned to stay on to sixth year.

Among those who had decided to stay on longer, one credited the MCR Co-ordinator (and, to a lesser extent, his mother):

“I had planned to stay on till about S4, but now I’ve learnt that I should stay on till S6. That’s my plan. […] [The Co-ordinator’s] basically told me that there will be a lot more opportunities in the future if you stay on longer as well, so… My mum’s even told me that, ‘stay on and you can maybe go straight to uni as well, instead of going through college and then going to uni’. So, I’d like to do that.” Pupil, S2, MCR

One pupil was planning to leave after fourth year and go to college. She indicated that her mentor was supportive of that decision. Her attendance at school had improved and her mentor was encouraging her to do things that would help her get the job she wanted after college.

Improved attendance

Pupils did not tend to identify improved attendance as something that MCR had helped with. However, this was largely because those interviewed felt their attendance had always been at least reasonably good.

One school staff member said they have data which shows an increase in attendance for care experienced young people taking part, which they put down to positive mentoring relationships. However, a local authority representative in their area noted that they did not have enough data yet to assess impact on attendance across all the schools taking part in the local authority area.

Increased attainment / achievement

There was a high level of agreement among pupils that MCR Pathways had made a positive impact on their attainment and achievement at school, with young people feeling that they were doing better in their schoolwork. This overlapped with increased self-belief that young people felt they now had (see ‘Increased academic confidence’ above).

Subject / course choice

There was also a high level of agreement that MCR Pathways had prompted young people to think more about the subjects they wanted to choose at school to help them get the kind of job they might want in the future. This was most commonly because mentors and MCR Co-ordinators had talked about it with pupils.

Key impacts on mentors and employers

Mentors interviewed had a range of backgrounds including working in the public, private and third sectors. Some had prior experience working with young people, while others did not. Mentors heard about the scheme in a variety of ways: through an email from their employer or on their staff intranet; through social media; on a TV programme; through a colleague; or from a flyer in a grocery store.

Mentors were motivated to take part because they wanted to help young people. One commented that she could have benefited from having someone to advise her that “there is more to life than school”. Another mentor said that, when they were younger, they had taken part in a lot of activities that were only possible because adults had volunteered their time so she “wanted to give something back”.

Mentors were supported to take part by their employer, and/or line managers working with them to make sure they had the time to dedicate to mentoring. Employers who were local authorities or organisations with a community focus were mentioned as particularly supportive.

“[My line manager] is supportive and it is really good, and there was absolutely no issue. I found out how much time and things that it would take and then I put that to her, and we just discussed how we could manage it.” Mentor, MCR

“[Mentor meetings go] in as red, so anyone looking at my calendar, I'm not available…Even the chief exec has tried to put a meeting in, and I've said to him, ‘no, sorry, it is my mentor meeting, I can’t change that.’ He is like, ‘fine, fair enough, we will move that’. So, I think we are very lucky with how supportive our employer is.” Mentor, MCR

Mentor and employer benefits

The scheme had some impact on mentor perceptions of young people. For example, one mentor said they now found it easier to understand young people in a one-to-one setting and it had changed how they interact with their own son. Another said it has helped them understand young people’s concerns, including their concerns about the future.

Mentors also felt the scheme had had a positive impact on their work and one mentor said they had encouraged their colleagues to sign up. One mentor felt that the MCR training had increased their ‘emotional intelligence’, so they are better able to pick up on situations at work and do something about them. Another had become interested in mentoring and coaching junior colleagues.

“It has definitely made me more interested in the mentoring side of things. I have been doing coaching training at work as well, which I don't think I would have done if I had not had this experience. It is nice to be able to see the impact you're having on someone.” Mentor, MCR

Mentors also described how mentoring had a positive impact on their own wellbeing. They described the experience as “fulfilling”, “energising” and “rewarding”. One mentor said:

“I think it has had a huge impact. I never don't look forward to the sessions, but I always go away delighted that I did them, I always take something. I injured myself over Christmas, and so when we met this week, I was quite sore and, actually, it took me away from that for a while. I always go away feeling much better for having been here and interacting with her.” Mentor, MCR

Mentor actions

Mentors generally indicated that they would continue mentoring at least until their mentee leaves schools or wants to stop – and commonly said that they would want to continue for longer.

Impacts summary

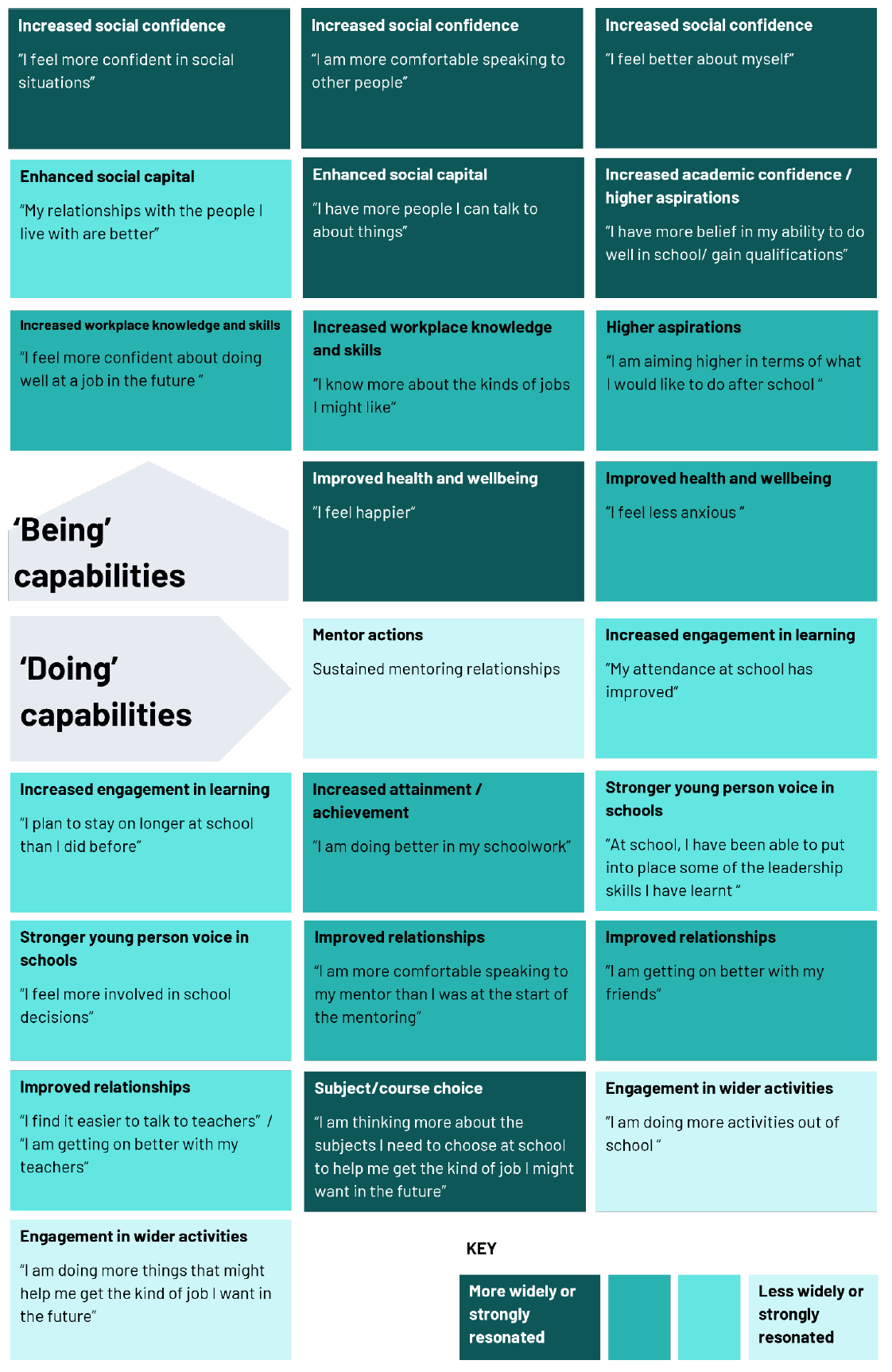

The infographic below provides a visual summary of the ‘doing’ and ‘being’ capabilities in relation to MCR Pathways. The statements are colour coded to illustrate those which resonated most widely or strongly (darker green) and those that resonated less widely or strongly (lighter green).

This visual summary should be read in conjunction with the section above, which provides further context and nuance to the ways in which participants felt the intervention had made a difference to them.

Infographic text:

‘Being’ capabilities

Capabilities that resonated more strongly

- Increased social confidence: “I feel more confident in social situations”

- Increased social confidence: “I am more comfortable speaking to other people”

- Increased social confidence: “I feel better about myself”

- Enhanced social capital: “I have more people I can talk to about things”

- Increased academic confidence/higher aspirations: “I have more belief in my ability to do well in school/ gain qualifications”

- Improved health and wellbeing: “I feel happier”

Capabilities that were somewhere in between

- Increased workplace knowledge and skills: “I feel more confident about doing well at a job in future”

- Increased workplace knowledge and skills: “I know about the kinds of jobs I might like”

- Higher aspirations: “I am aiming higher in terms of what I would like to do after school”

- Improved health and wellbeing: “I feel less anxious”

- Enhanced social capital: “my relationships with the people I live with are better”

‘Doing’ capabilities

Capabilities that resonated more strongly

- Subject/ course choice: “I am thinking more about the subjects I need to choose at school to help me get the kind of job I might want in the future”

Capabilities that resonated less strongly

- Mentor actions: “Sustained mentoring relationships”

- Engagement in wider activities: “I am doing more activities out of school”

- Engagement in wider activities: “I am doing more things that might help me get the kind of job I want in the future”

Capabilities that were somewhere in between

- Increased attainment/ achievement: “I am doing better in my schoolwork”

- Improved relationships: “I am more comfortable speaking to my mentor than I was at the start of the mentoring”

- Improved relationships: “I am getting on better with my friends”

- Increased engagement in learning: “My attendance at school has improved”

- Increased engagement in learning: “I plan to stay on longer at school than I did before”

- Stronger young person voice in schools: “At school, I have been able to put into place some of the leadership skills I have learnt”

- Stronger young person voice in schools: “I feel more involved in school decisions”

- Improved relationships: “I find it easier to talk to teachers / I am getting on better with my teachers”

Broader impacts

To what extent has the MCR Pathways embedded mentoring and leadership?

MCR Pathways, at the time of writing, had been embedded in all 30 Glasgow schools (mainly from 2014/15 onwards, after the first school came on board in 2007/8) and in 89 schools across the rest of Scotland, with these schools coming on board from 2017/18 onwards. There was an overall sense among respondents that it is important for organisations like MCR to take the lead on embedding mentoring in schools, since school staff have other priorities and do not have the capacity to do this kind of work.

There was limited evidence, however, that the MCR Pathways had embedded mentoring more widely across the local authority areas we visited outside of Glasgow. One local authority stakeholder reported that they wanted to see more data on the impact before deciding whether to roll it out to other schools in their area.

There was also limited evidence of MCR Pathways leading to schools broadening their links with other services or organisations that can support young people. Schools were already working with other organisations to improve these type of opportunities, such as Career Ready, Barnardo’s, and local Rotary Clubs. MCR Pathways is, therefore, seen as “one of a suite of interventions”. One school staff member said that mentors’ connections had led to more local work experience and volunteering opportunities for young people in that school. However, at a local authority level, it was hoped that MCR Pathways would do more to increase these kinds of opportunities.

To what extent has the MCR Pathways developed a positive relationship with DYW, SDS and the Promise?

Representatives of other organisations working with young people: DYW, SDS[19] and the Promise, generally felt that their organisation had a positive working relationship with MCR, and vice versa.

Representatives of these organisations shared various examples of partnership working. For example, at a senior level, MCR and the Promise met to discuss the definition of “care experienced”, with MCR also offering support in raising local awareness of the Promise. At a school level, mentors are encouraged to complement the work of SDS by supporting their mentee with things like college applications. MCR and DYW work together on employer engagement opportunities called ‘Talent Tasters’. There were also examples of individual staff moving employment between these organisations which helped share knowledge. SDS also highlighted that some of their staff are mentors.

Representatives noted that these organisations have a shared remit in supporting young people to move into positive destinations. One stakeholder said that MCR Pathways complements their work in being able to offer weekly one-to-one support, which their organisation cannot provide. However, there was a wider sense among participants that more could be done to avoid duplication of effort in this space. For example, some stakeholders compared MCR Pathways with a programme offered by Career Ready and felt these interventions were available to similar[20] cohorts of young people and had similar aims.

Contact

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback