Green land investment in rural Scotland: social and economic impacts

Outlines the findings of research into the range of potential social and economic impacts relating to new forms of green land investment in rural Scotland.

2. Methodology

The first step of the research involved a literature and evidence review to develop and verify key concepts and definitions such as ‘green land investment’ and ‘rewilding’.

Next steps included case study selection, stakeholder identification and participant recruitment, and fieldwork with qualitative data collection through interviews and workshops. In six case studies in different parts of Scotland, 54 interviews and six workshops with 96 participants were conducted.

Thematic analysis built understanding of current and likely future social and economic impacts of green land investment.

This research has utilised a largely qualitative approach. This means that the focus of data collection was to capture people’s perceptions, opinions, and experiences. As described in this chapter, those who participated in the research were identified and invited to participate to gather the potential diversity of views, and therefore this research does not claim to be representative of the entire population of the case studies, or beyond, that of all of rural Scotland. Nonetheless, across the qualitative dataset collated, common themes can be identified, and experiences reported by the participants provide valuable insights that help us to understand the range of perceived, potential, and actual social and economic impacts relating to green land investment activities. This chapter outlines the qualitative approach (i.e. data collection and analysis) and use of secondary data analysis to characterise the case studies, as well as the limitations in this research that influence how we can draw conclusions from the data (for example, disentangling causes and effects).

The findings reported (Chapter 4) are based on the qualitative data analysis. Fieldwork was undertaken between May and September 2023.

This research has involved three key stages:

i. an evidence and literature review, to develop and verify key concepts and definitions, including ‘rewilding’;

ii. capturing current, historic, and diverse rural lived experiences through interviews and community workshops;

iii. building understanding of likely future impacts (over different timescales) and the opportunities to maximise the benefits to rural communities from green land investments, and minimise negative impacts (informed by interview and workshop findings).

This section provides more detail of the data collection and analysis undertaken.

2.1 Developing a definition of green land investment for a Scottish context

A review of academic and grey literature was undertaken to develop a definition and outline a typology of green land investments, and to build an understanding of existing definitions of ‘rewilding’. A rapid evidence review was undertaken, based on a protocol comprising the questions, scope, and methods including search strategy and inclusion/exclusion criteria.

In addition, conventional and non-conventional searching techniques (e.g. keyword searches, targeted requests, etc.) were employed. A narrative synthesis of results describing the different motivations behind land acquisition and investment is presented in Chapter 3.

A decision was made to exclude literature solely on green land investments in the Global South, where large-scale land acquisitions are commonly associated with human rights abuses, lack of transparency and consent of users, and dispossession (McMorran et al., 2022a). For this rapid evidence review, 32 articles, 69 news and magazine articles, and 23 additional sources (discussion/position papers, blog posts, reports, and web pages) were found to be relevant. However, the academic literature contained very few relevant studies on Global North cases, and only three focused on Scotland.

Verification and adaptation of the typology, as well as further developing understanding of landowner and investor motivations, was informed by discussions with the Research Advisory Group for this project, as well as members of the Stakeholder Advisory Group for the Scotland’s Land Reform Futures project[8], part of the Scottish Government's Strategic Research Programme 2022-27. This was also the focus of in-depth, semi-structured interviews with landowners, representatives of landowning organisations, and managing agents/land managers. These interviewees were identified according to their role with the case study landholding (see Section 3.3.2). These interviews sought to understand landowner and investor motivations, private sector interests and awareness of perceived/actual impacts on local communities of place and communities of interest due to green land investment, as well as existing practices around community engagement.

The interview guide, participant information sheet and consent form are presented in Annexes 2, 4, and 6.

2.2 Creating a formal definition of ‘rewilding’ for use by the public sector in Scotland

In addition to an extensive literature review, an online interactive workshop was designed and facilitated to identify a formal definition of ‘rewilding’, for use by the public sector in Scotland. Workshop participants included predominantly representatives from the public sector, in particular agencies and departments whose work relates to nature management. Other participants included representatives from academia, environmental non-governmental organisations, and other UK public sector administrations. Prior to the workshop, each participant received a summary version of the literature review to inform discussions. The literature review and workshop findings are described in full in the separate report: ‘Defining Rewilding for Scotland’s Public Sector’ by Kerry Waylen and Acacia Marshall (published July 2023).

2.3 Identifying the socio-economic impacts of green land investments in rural Scotland

2.3.1 Case study selection

A purposive sampling technique was used to identify six critical[9] case study landholdings and associated rural communities. Initially a long list of projects was collated that aligned with the definition of green land investment outlined in Section 3.2. This list was derived from web searches, literature reviews, exploration of the Woodland Carbon and Peatland Carbon Codes, researcher knowledge, and in discussion with members of the project’s Research Advisory Group (comprising members of different Scottish Government policy teams, independent land consultants, and senior land use academics).

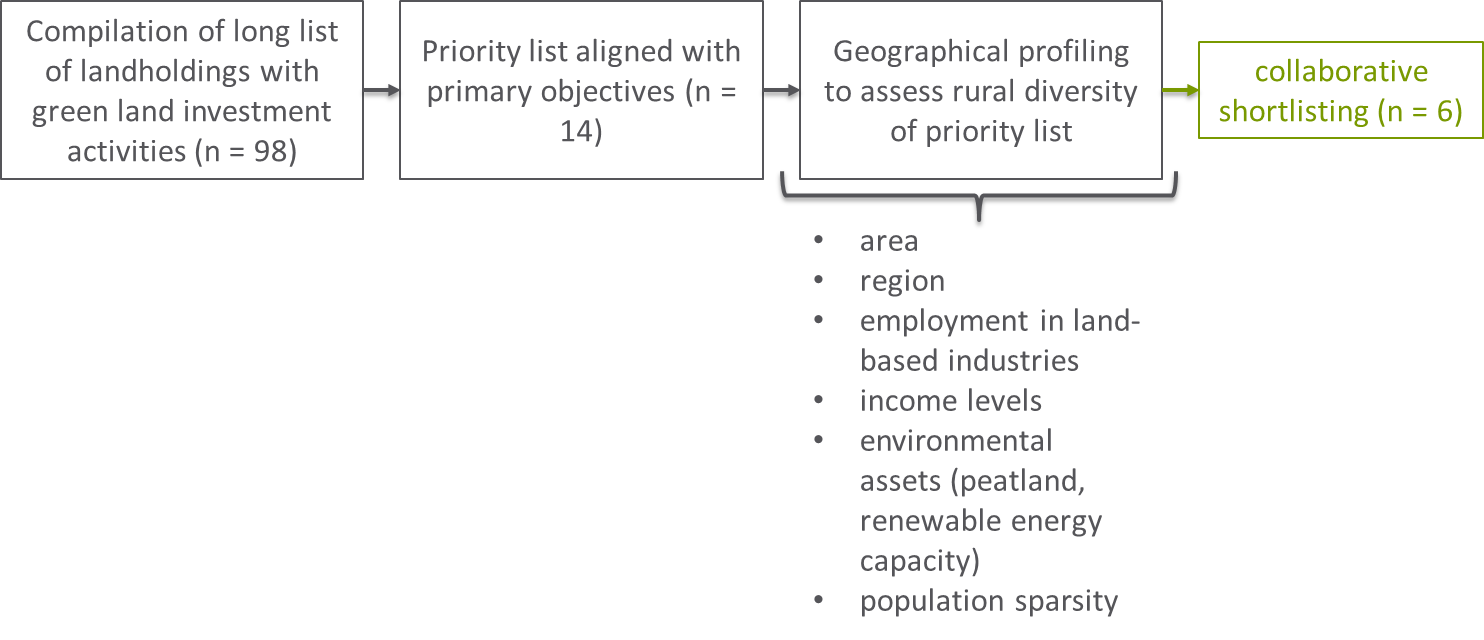

As described in more detail in Section 3.2, four primary motivations for green land investment were targeted in case study selection: (i) financial returns; (ii) environmental/social impacts; (iii) operational impacts (e.g. in/offsetting); and (iv) reputational impacts. Many investor-owners had several, or all of these motivations for their projects. Across all the landholdings, it was recognised that there was a range of diverse environmental activities ongoing, including rewilding, renewable energy development, afforestation, and peatland restoration, and case study selection sought to include this diversity (i.e. drawing examples of each ‘primary objective’/motivation, as identified from web and literature searches regarding the landholding). Duration of landownership was also a key criterion, with case studies representing changes in landownership over different timescales. Case study selection also sought to include a diversity of rural community contexts, for example through analysis of socio-economic indicators. From this long list, considering these criteria, and in discussion with the Research Advisory Group (and members of the Scotland’s Land Reform Futures project Stakeholder Advisory Group), six final case studies were identified that represented the diversity of green land investment motivations, activities, and rural contexts in Scotland. A summary table outlining the characteristics of the six anonymous case studies is presented in Table 1 (see below). Figure 1 describes the case study selection process.

To support anonymisation of the inputs from research participants described in this report, the demographic, economic and geographical diversity of the case studies are illustrated using outline summaries of the group, which were produced from detailed quantitative and spatial analysis of secondary datasets (Table 1).

Green land investor models included individual ownership, ownership by corporations, and where corporations provided land management services to private landowners/investors. Ownership duration ranged from multi-generational ownership, ownership within the past two decades, within the past three years, and within the past year. Activities likewise varied, but included afforestation, rewilding, peatland restoration, and renewable energy. Table 1 illustrates key characteristics and changes evident in secondary data related to the six case study locations.

Table 1. Environmental, demographic, and economic summary characteristics for the six case studies.

Figures marked (*) were calculated for the estate area, plus the estimated area within 15 minutes’ drive-time of the landholding’s boundaries.

Indicator

Area (ha)

Narrative description of six case studies

The case studies covered a diversity of areas: the largest was more than 30 times the size of the smallest.

Indicator

Woodland area (change in ha, 2011-20)

Narrative description of six case studies

Four of the six case studies observed some woodland expansion from 2011 to 2020.

Indicator

Population* (2021)

Narrative description of six case studies

The estate (and nearby communities) which had the largest population in 2021 had a total population which was more than ten times larger than that of the least populated case study.

Indicator

Population change* (%, 2001-21)

Narrative description of six case studies

Four of the six case studies and nearby communities saw an increase in total population from 2001 to 2021.

Indicator

Gross Value Added (GVA)* (£m, current prices, 2020)

Narrative description of six case studies

The value of economic output was over 20 times greater in the case study (including nearby communities) with the largest GVA, compared with the smallest.

Indicator

Employment in land-based sector and tourist sector* (% of residents, 2011)

Narrative description of six case studies

In three case studies, more than one in ten employed residents (of the case study area, and accessible communities) were employed in tourism (i.e. ‘Accommodation and food service’). In one case study, more than 10% of residents were employed in the land-based industries.

Note that comparisons of case studies given are deliberately ‘fuzzy’ and were rounded down to the nearest ten ‘times’ to maintain case study anonymity. ‘Gross Value Added’ is the net value of goods and services produced in the area.[10]

2.3.2 Qualitative data collection

For each case study, stakeholder analysis was undertaken, to identify the diversity of lived experience, anticipate likely discussion points during fieldwork, and to develop a shortlist of potential interviewees. The stakeholder analysis sought to identify a range of rural stakeholders, including both representatives from communities of place that were located on or adjacent to the case study landholdings, as well as communities of interest, including owner-occupier farmers, tenant farmers and crofters, those employed on rural estates (or who are recent ex-employees), rural business owners, and others who were identified as likely to be/have been impacted by green land investment activities or land use change. Potential interviewees were initially identified through web searches, contacting community organisations (e.g. community councils, development trusts, etc.) and membership organisations (e.g. Scottish Tenant Farmers Association, National Farmers Union Scotland, etc.), and through researcher networks. Individual gatekeeper bias was avoided as far as possible through contacting multiple local gatekeepers.

In-depth, semi-structured individual or small group interviews (2-3 people) were undertaken with representatives of both communities of place (i.e. community councillors) and communities of interest (e.g. local business owners, farmers/crofters, etc.) associated with the case studies. The purpose of these interviews was to develop an understanding of the impacts of green land investment on people and communities. At least eight people were interviewed in each case study and recruited according to a purposive sampling technique based on the stakeholder analysis. The interviewees included a mix of ages and genders, as well as hard-to-reach groups (e.g. ex-employees of the case study landholdings, those on low incomes or with other protected characteristics). Interviews were digitally recorded (with informed consent from the interviewees) and transcribed. The participant information sheet, consent form, and interview guide are presented in Annexes 1, 3, and 5. Table 2 (below) outlines the number and type of interviewees. Across all participants (interviewees and workshop participants), 60% were male and 40% were female, and ages ranged from people in their twenties to seventies[11].

Finally, community-based workshops (at least one per case study) aimed to interrogate the historic, current and potential short-term and longer-term implications of changes in rural land use and ownership in the locality. In particular, workshop design encouraged participants to consider the changes that they had observed locally over living memory, and to share their ideal future visions (after Duckett et al., 2017) to elicit local community perspectives on the impact of green land investment in their local area. The workshop discussions also considered experiences of landowner-community engagement and the available options for partnership working, collaboration, and effective engagement between the rural community and local green landowners and investors. The workshop facilitation guide is presented in Annex 9.

The workshops were open to all members of the local community, and advertised openly through local channels (e.g. community noticeboards, mailing lists, Facebook groups). Invitations to participate in the workshops were circulated to local community groups and individuals identified in the stakeholder analysis. The workshops were held locally in accessible community-based venues (e.g. village halls, church halls, and community centres), with refreshments provided for participants. Travel expenses and childcare costs were reimbursed to participants where requested, and this was advertised to ensure that cost was not a barrier to participation.

Focus group discussions were carefully facilitated to ensure all participants were able to contribute and no single voice or group dominated. Participants were asked to follow the Chatham House rule[12]. Focus group discussions were digitally recorded (with informed consent from participants) and transcribed. The participant information sheet and consent form for the community workshops are presented in Annexes 7 and 8.

Table 2. Number and type of case study interviewees and workshop participants

Case Study 1

Number of Interviewees: 8

Interviewee Types:

- Local business owner

- Community councillor

- Landowner representatives (x2)

- Community representatives (x 2)

- Estate employees (x 2)

Number of Workshop Participants: 17

Total Participants: 25

Case Study 2

Number of Interviewees: 8

Interviewee Types:

- Neighbouring landowner

- Intermediary company representative

- Community representatives (x 3)

- Land managers (x 2)

- Tenant farmer

Number of Workshop Participants: 13

Total Participants: 21

Case Study 3

Number of Interviewees: 8

Interviewee Types:

- Landowner representatives (x 2)

- Community representatives (x 3)

- Crofters (x 2)

- Neighbouring land manager (x 1)

Number of Workshop Participants: [No participants; researchers participated in alternative online community event]

Total Participants: 8

Case Study 4

Number of Interviewees: 11

Interviewee Types:

- Tenant farmers (x 5)

- Community representatives (x 2)

- Local business owner

- Estate employee

Number of Workshop Participants: 53

Total Participants: 64

Case Study 5

Number of Interviewees: 11

Interviewee Types:

- Landowning company representative

- Land manager

- Local business owner

- Local tenant farmer

- Owner-occupier farmer

- Community representatives (x 3)

- Former estate employees (x 2)

- Estate residential tenant

Number of Workshop Participants: 10

Total Participants: 21

Case Study 6

Number of Interviewees: 8

Interviewee Types:

- Landowning company representative

- Land manager

- Neighbouring land managers (x 2)

- Neighbouring tenant farmer

- Community representatives (x 2)

- Local business manager

Number of Workshop Participants: 3

Total Participants: 11

2.3.3 Qualitative data analysis

Anonymity and confidentiality were primary considerations in this research. All interview and workshop transcripts were anonymised prior to analysis. This involved the careful removal of all identifiers of individuals, places, organisations, or community groups. Data was stored securely in password-protected files on James Hutton Institute servers.

All qualitative data collected from interviews and workshops underwent thematic analysis (Clarke and Braun, 2017) using the NVivo tool to determine the core and sub-themes, commonalities, and divergences of narratives across interviewee types. Co-analysis across the research team and the use of a shared analytical framework supported rigorous and reflective analysis. The key themes emerging are the focus of Chapter 4.

2.4 Project limitations

This research is timely and has largely been met positively by those approached to participate as interviewees and workshop participants. However, limitations arose with regard to landowner non-response (and on one occasion declining to participate), which has limited our understanding regarding green land investor-owner motivations across all case studies. Non-response and declining to participate (either as interviewees or workshop participants) was also a feature of approaching members of communities of place and interest (e.g. estate employees). In some contexts, estate employees were unable to participate due to having signed confidentiality agreements with their employer. Others, such as commercial tenants, expressed their wish not to discuss business arrangements. There were also indications that media enquiries to potential participants had previously taken their time, which meant they were less willing to participate in the research. Participants also highlighted the challenges and limitations of case study/interviewee anonymity in small communities, and this was likely a reason for some choosing not to participate in community workshops. In one case, participants raised concerns regarding possible implications from participating in terms of their relationships with the landowner. In at least two case studies, community members expressed their perceived vulnerability in sharing their views openly, and farming tenants believed that their livelihoods could be threatened if they spoke negatively about the green land investor-owners’ land management practices.

Another key limitation was the limited timescale for this research, which impacted on the research team’s ability to build the types of relationships necessary to undertake sensitive research. This limitation was mitigated to some extent through working closely with multiple gatekeepers, seeking to be aware of and respond to local concerns, and maintaining ongoing contact. Follow-up presentations and discussions will be arranged with case study community groups and green land investor-owners regarding the key findings from this research. The variation in numbers participating in the workshops (see Table 2) may be related to a combination of how well details of the workshop were communicated with communities of place, the perceived value and potential impact of the research, and the timeliness of this issue in the local area (i.e. whether community members had recently experienced landownership and land use change or not). In one case study, despite widespread promotion of the community workshop, no participants attended. Two people who had indicated their intention to attend were later interviewed. In order to gather wide community views in this case study, the research team attended an online event organised by a local community group, introduced the project and gathered feedback. This feedback has informed the analysis, but direct quotes were not captured during this event.

Finally, there remain challenges in disentangling processes of change affecting rural communities (for example, changes to land-based industries and associated employment) from those that are driven more directly by landownership and land use change associated with green land investment. Limitations in secondary data availability (for example, small area-level data from the 2022 Census have not been published, as of September 2023) have restricted how well local changes can be observed that align with transitions in landownership and land use. Similarly, in order to support case study and participant anonymity, only generalised descriptions of the final six case studies (featuring broad descriptions of the case studies as a group, and rounded comparisons of magnitude) have been published in this report. Additionally, it was not always clear what was the influence of ‘green land investment’ rather than traditional private ownership in driving social and economic impacts (for example, relating to issues of scale and concentration; community involvement in land use decision-making). This point is considered further in the Conclusions (Chapter 5).

Contact

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback