Building a New Scotland: Social security in an independent Scotland

Sets out the Scottish Government’s proposals for social security in an independent Scotland.

Social security in the UK

Social security spending in the UK and in Scotland

The UK Government is currently responsible for the provision of most working-age and pension-age social security benefits in Scotland, England and Wales.[9] These are known collectively as ‘reserved benefits’.

Reserved benefits are for the most part delivered by the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP), with others delivered by His Majesty’s Revenue and Customs (HMRC) and local authorities.

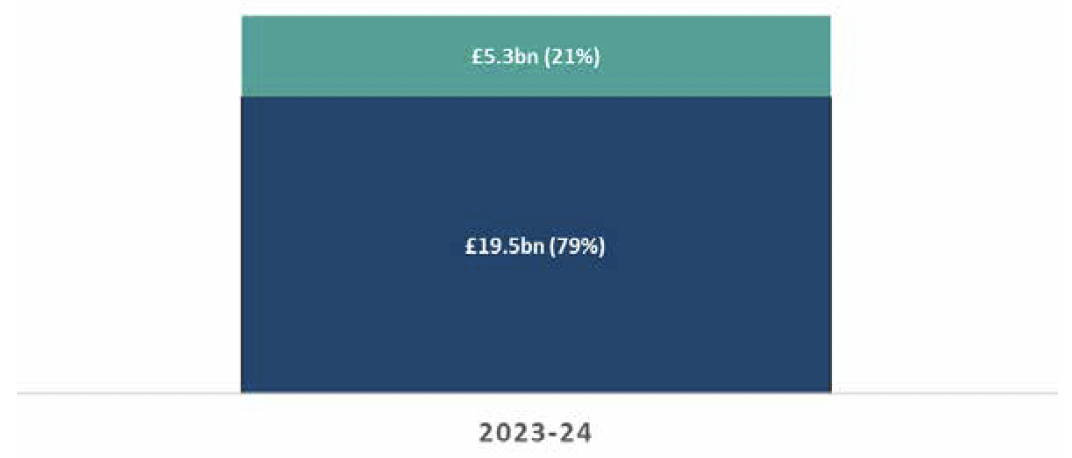

In 2023-24, it is estimated that around 79% of benefit spend (including pension-age benefits) in Scotland is reserved to Westminster.[10] Forecasts suggest spend of around £24.7 billion on social security benefits in Scotland in the same year – £19.5 billion of which is UK Government spend on reserved benefits. See Figure 1, below. Annex A has more details on reserved working-age benefits. Social security is paid for by revenue raised through general taxation.

Note: Reserved expenditure includes State Pension, Universal Credit, legacy benefits and benefits administered by HMRC. Devolved expenditure includes benefits devolved to Scotland including benefits currently delivered by DWP through agency agreements (e.g. Personal Independence Payment). It excludes some very small benefits which are not part of the SFC’s remit such as Young Carer Grant and Job Start Payment. The estimate is based on taking Scotland benefit shares from outturn information for devolved benefits and applying them to the Spring Budget forecasts. Expenditure in Scotland uses the Scottish Fiscal Commission May forecasts.

Source: Scotland’s Economic and Fiscal forecasts (SFC, 2023), Spring Budget forecasts (UK Government, 2023), Scotland Benefit Expenditure by Country and Region (UK Government, 2022)

Scotland Benefit Expenditure and Caseload (UK Government, 2022), Scotland Tax Credits Statistics (UK Government, 2021), Scotland Child Benefit Geographical Statistics (UK Government, 2022)

Although the UK Government is responsible for most social security spending, the Scotland Act 2016 devolved some social security powers to the Scottish Parliament, which enabled Scotland to set up its own system. Social Security Scotland now delivers devolved Scottish benefits under these powers. Although constrained in several ways, it has its own distinct approach, discussed further in the next section.

These benefits are partly paid for through additions to money the Scottish Government receives from the UK Government. The additions are called ‘Block Grant Adjustments’ and the amount of funding received through these adjustments is based on how much the UK Government spends on the equivalent reserved benefits.

Changes to UK Government policy and associated spend impacts on how much money the Scottish Government receives through these additions. For example, if the UK Government reduces spending on benefits delivered in England and Wales, the Scottish Government would receive less funding for devolved benefits.

If the Scottish Government wants to increase the value of, or change the eligibility criteria of, Scottish social security benefits, it must fund this with its own fixed budget. For example, no additional funding is allocated in Block Grant Adjustments for the seven new benefits that are only available in Scotland. In this financial year the total additional investment is over £750 million[12] above the level of funding forecast to be received from the UK Government through Block Grant Adjustments – money which will go directly to people who need it the most. Over £540 million of this will fund new payments which are only available in Scotland – such as our game-changing Scottish Child Payment.

The decision to prioritise these new benefits, and the additional spend on carers and disability benefits, affects the funding available to spend on other public services in Scotland. While this is a challenge that all governments face, it is made more difficult by the limited economic and fiscal powers the Scottish Government currently has to manage its budget both within and across years. Added to this is the uncertainty created by having to anticipate wider changes in the budget resulting from UK Government policy changes to both tax and social security, which impact on the total budget available to the Scottish Government.

These current arrangements mean there are real constraints on what action the Scottish Government can take on social security, especially to provide support in times of crisis like the pandemic and the cost of living crisis.

UK carer and disability benefits

Before the devolution of some aspects of social security through the Scotland Act 2016, carer and disability benefits in Scotland were the same as those in the rest of the UK.

Carer’s Allowance developed in the UK from the introduction of the ‘Invalid Care Allowance’ in 1975. Until 1986, married women were not eligible for the benefit, and it was only from 2002 that carers aged over 65 could apply. It is fair to say that the benefit has remained largely unchanged in the last twenty years or so, being available to unpaid or informal carers who provide 35 hours or more of care a week for people receiving certain disability benefits and earning below a certain amount. In 2023-24 it provides £76.75 a week and the earnings threshold (that is how much a person can earn after allowable deductions and remain entitled to the benefit) is £139 per week. As such it is the lowest of all working-age benefits. And, while there have been significant social changes, unpaid care is still predominantly provided by women, with almost 70%[13] of Carer’s Allowance recipients female.

There have been calls for improvements to Carer’s Allowance through the years, most recently the All-Party Parliamentary Group on Poverty’s inquiry on the adequacy of UK benefits called again for Carer’s Allowance to be increased in line with equivalent out-of-work benefits – as we have already done in Scotland through our Carer’s Allowance Supplement. In our own work with carers and the organisations that support them, we identified and set out plans to deliver further changes to better support carers to provide care for loved ones in a meaningful and sustainable way while still being able to work, attend education and have full lives away from caring.

The disability benefits landscape is more complex. The benefits devolved to Scotland were Attendance Allowance, Severe Disablement Allowance, Disability Living Allowance, Personal Independence Payment (PIP) and parts of the Industrial Injuries Disablement Scheme. Other disability premiums remain reserved to the UK Government. Arguably the largest and most complex of these benefits is PIP which was introduced in 2013 to replace Disability Living Allowance for adults of working age.

PIP has been widely criticised for a number of reasons including routine private sector assessments, a time-limited definition of terminal illness and high numbers of decisions that need to be appealed.[14], [15]

In Scotland, PIP has been replaced by Adult Disability Payment, while the Child Disability Living Allowance has been replaced with Child Disability Payment: these are described in more detail later on in this paper. Many people receiving devolved disability benefits will continue to be eligible for reserved benefits or premiums. The UK Government have initially agreed that Child Disability Payment and Adult Disability Payment can be used as qualifying benefits to ‘passport’ disabled Scottish people to these premiums but have indicated that this may be reviewed if Child Disability Payment or Adult Disability Payment change in the future.

Disability and ill health benefits are not immune from the current UK Government’s attempts to reduce and limit social security spend. The content of the Health and Disability White Paper – in particular, the planned end to Work Capability Assessments – will reduce the incomes of many who are in poor health and expose them to the risk of benefit sanctions.

The devolution settlement means that Scottish Government powers to deliver carer and disability benefits will always be compromised by the need to function effectively within a wider reserved social security and tax system. With independence the Scottish Government could do more to develop an integrated system of support for unpaid carers and disabled people, reducing the complexity of the system to make sure that everyone receives the full level of support they need and are entitled to.

Universal Credit and legacy benefits

With full powers over policy and spending, the Scottish Government would make different choices about the wider social security system. This is true in many aspects of policy, with the main reserved benefit for people of working age, Universal Credit, being a key example of the inadequacies and unfairness of the current system.

Universal Credit is not just an unemployment benefit. Many people who receive Universal Credit are in work but on low incomes. Eligible unpaid carers and disabled people on low incomes will also receive Universal Credit.

The UK Government introduced Universal Credit in 2013. It provides a single monthly payment for support previously provided by six working-age benefits, known as the ‘legacy benefits’. These include Housing Benefit, Income Support and Job Seekers Allowance.

Ten years on, Universal Credit is not fully rolled out and many people continue to receive legacy benefits. Only in summer this year did DWP begin to roll out its ‘Move to UC’ initiative which aims to move all people currently receiving only Tax Credits onto Universal Credit. Tax Credits are now set to end in 2026.

The UK Government claimed that Universal Credit would ‘introduce greater fairness to the welfare system by making work pay and make sure that people are better off in work than on benefits’.[16] It also claimed that Universal Credit would be simple to claim and ‘responsive’ to changes in circumstances, and would encourage household budget management by providing payments monthly in arrears.

However, the evidence suggests a very different picture:

- it is estimated that around half of households receiving Universal Credit are already in work[17]

- the ‘responsiveness’ builds in insecurity, as benefit levels change month on month, making it difficult for households to budget[18]

- and the ‘digital first’ approach can act as a barrier to households to both apply for and maintain their application or ‘claimant commitment’[19]

Furthermore, people moving from legacy benefits onto Universal Credit must make completely new applications or face having their benefits stopped. This is in sharp contrast to the Scottish Government’s approach, where people moving from a UK benefit to its devolved Scottish equivalent do not need to make a new application.

Moreover, there is no guarantee that entitlement and income will be protected when moving from legacy benefits to Universal Credit. Although some households are better off under Universal Credit, others are worse off. DWP analysis shows that, of the 2.6 million households remaining on legacy benefits in April 2022, approximately 900,000 households (35%) would have a lower entitlement on Universal Credit (see Figure 2).[20]

Note: Estimates of household’s UC entitlements by hierarchical legacy benefit type – legacy caseload in April 22 (including the impact of changes to the taper rate and work allowances from the 2021 Budget).

Source: DWP Completing the move to Universal Credit

Those applying for Universal Credit must do so on a ‘household’ basis. This has significant impacts on women, especially those with dependent children. A single monthly payment for couples risks women’s financial independence and autonomy. The Scottish Government is currently working with DWP to explore introducing ‘split payments’ to people applying for Universal Credit in Scotland to mitigate this issue. To do so will require changes to Universal Credit systems, which will only apply in Scotland. The Scottish Government will pay for these changes and the work will be built into DWP planned systems changes and updates, giving us very little control over the timeframes. While it is undoubtedly the right thing to do, it is made more expensive and complex due to interactions across both reserved and devolved systems.

Universal Credit also means that rent is no longer automatically paid to a landlord. Although people in Scotland have the choice to have their Universal Credit award paid directly to their landlord, there remains a risk that some households will fall into rent arrears.

A five-week wait for a first payment of Universal Credit is pushing households into debt, with the only support available meantime being ‘budgeting loans’ which must be repaid through deductions from Universal Credit payments.[21] These repayments mean that future Universal Credit monthly payments are reduced. As the value of the monthly payment is already considered by many to be inadequate, this puts households under increased financial pressure.

Arguably the main difficulty with Universal Credit is that it simply does not provide enough money to households that receive it. The true value of the benefit compared to earnings and inflation has been declining over time. The All-Party Parliamentary Group on Poverty’s findings on the inadequacy of Universal Credit, drawing on evidence from the Robertson’s Trust and the Trussell Trust, found that the basic allowance does not provide enough to cover essentials like food and utilities.[22]

This is compounded by age discrimination baked into the policy which means that parents under 25 receive a lower level of benefits than parents over 25. Known as the ‘young parent penalty’, the Universal Credit standard allowance for a couple under 25 is £90 a month less than for an otherwise similar couple over 25. Yet the cost of living is the same – housing, bills, and food all cost the same.

Figure 3 shows Universal Credit entitlement for a single person aged 25 or over with one child, renting privately in Stirling, as a percentage of average earnings in Great Britain (GB). The household is assumed to use their full Local Housing Allowance and to have no earnings.

Note: Scottish Government calculation. Comparing the average weekly earnings (ONS) for Great Britian to the estimated UC entitlement for a single parent with a child and local housing allowance in Stirling from April 2013 to 2023. The figures presented here are weekly averages with UC entitlement as a percentage of the average weekly earnings.

Sources: Abstract of DWP benefit rate statistics – GOV.UK(www.gov.uk), EARN01: Average weekly earnings – Office for National Statistics (ons.gov.uk), Local Housing Allowance Rates: 2022-2023 – gov.scot (www.gov.scot), https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/benefit-and-pension-rates-2022-to-2023/proposed-benefit-and-pension-rates-2022-to-2023

This shows that the household’s Universal Credit award has decreased from around 50% of average GB earnings in 2013 to around 40% in 2022. This decrease stems from UK policies including the benefit freeze between 2016 and 2020, the removal of the family element in 2017, multiple freezes to Local Housing Allowances, and the removal of the temporary £20-per-week uplift in October 2021.[23] Some family types, such as those subject to the two-child limit or the benefit cap, have experienced larger losses. These policies are explored further below.

As the flagship benefit of the current UK Government, the problems with Universal Credit are considerable but not insurmountable. In an independent Scotland, Universal Credit could be reformed in the short term to make it fairer, while a new system is being developed that goes beyond what that benefit was originally meant to achieve.

The impacts of welfare reform

Beyond Universal Credit, a range of policy measures has been introduced as part of the UK Government’s welfare reform agenda. The following changes have made it very difficult for people to survive on benefits:[24], [25]

- the benefit cap – frozen between 2016 and 2022, despite inflation, this limits the amount of annual benefits that a household can receive to £14,800 for single adults if they live alone with no children, or £22,000 for couples or single households with children.[26] This compares to a median UK disposable income of £32,300 in 2022.[27]

- the two-child limit, under which a household will only receive the child element of Universal Credit or Child Tax Credits for their oldest two children, penalising larger families. The family element of Universal Credit and Child Tax Credits, which provided an additional payment for families with children, was withdrawn in 2017 at the same time as the two-child limit was imposed.

- the bedroom tax, which penalises households in the social rented sector who have so- called ‘spare rooms’. The Scottish Government fully mitigates the bedroom tax by way of Discretionary Housing Payments.

- the benefit freeze, which, from 2016 to 2020, kept Universal Credit rates the same, as the cost of living increased. Although rates have increased with inflation since 2020, they will never catch up to the same level they were pre-2016 through statutory uprating alone.

Most of these changes were introduced by the UK Government to ‘make work pay'[28] but many households impacted by these changes are already in paid work, and in many other cases, have at least one adult who is unable to work, for example, unpaid carers and people who are unable to work because of sickness or disability.

We know that people who have an extended period providing unpaid care are likely to have poorer financial outcomes than their non-caring peers.[29] For tens of thousands, their caring role reduces their capacity to take on paid employment. As well as the immediate impact on incomes, this has a long-term negative impact, as unpaid carers, predominantly women, have less opportunity to save for retirement.

In a system focused on keeping income replacement levels low to encourage people into work, financial challenges can be compounded when circumstances mean that paid work is not a viable option. This can mean that a household is entirely dependent on income from social security – for example if a person is providing care to a partner who is disabled or has a long-term illness and it affects their ability to take up paid work. We know that people with a long-term illness or disability are more likely to experience poverty[30] and that poverty has significant impacts on people’s physical and mental wellbeing.[31]

Layered on top of the caps and limits, benefit sanctions can reduce benefits payments even further. Analysis by the University of Glasgow, published in March 2022, reviewed evidence showing that sanctions led to ‘worsening job quality and stability in the longer term’, and to people returning more quickly to claiming benefits or exiting the labour market entirely.[32] In addition, the imposition of sanctions was associated with ‘an increase in material hardship, including food deprivation’, and with poorer physical and mental health.

The Joseph Rowntree Foundation, in its series of destitution studies focusing on the UK social security system, found that ‘benefit sanctions were a key driver of destitution’ at a number of points over the last decade.[33] Despite this, the UK Government is pushing ahead with plans to introduce more work conditionality for more vulnerable groups, including families with young children and those with ill-health.

Finally, the inadequacy of UK social security has been evident through the pandemic and now in the cost of living crisis. While Universal Credit was topped up by £20 per week during the first phase of the pandemic – indicating that the previous level was inadequate – this was swiftly removed once restrictions began to be lifted. Similarly, the UK Government was forced to bring in emergency legislation so that additional payments could be made to mitigate the worst impact of the cost of living crisis. If benefits had kept pace with inflation, instead of being frozen and capped, this emergency action may have been unnecessary. UK benefits were broadly uprated by inflation (reflected by the annual September rate of CPI) in April 2023, which was welcome, but without additional increases they will not return to their true original value.[34]

Piecemeal, inflation-level increases will not address the fundamental inadequacies of the current income replacement benefits and the harms of welfare reform, as was set out clearly in the All-Party Parliamentary Group on Poverty’s inquiry in June this year on the adequacy of social security.[35] That report draws on a wide range of evidence from across the third sector and academia. It provides stark evidence that current benefit levels are not sufficient to allow people to live sustainably or comfortably. That report goes on to make a series of recommendations including the introduction of an Essentials Guarantee – as advocated for by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation.[36] The very basic principle of an Essentials Guarantee is that at a minimum social security should protect people from going without essentials – such as food, utilities and vital household goods. The report seeks to tie the level of social security paid to need rather than arbitrary values.

The Joseph Rowntree Foundation report recommends that the level is set at £120 per week for a single household and £200 per week for a couple; that these levels are reviewed regularly and set independently of government, and that the award cannot be reduced below this level due to deductions such as debt repayments, or artificial limits such as the benefit cap. The Scottish Government has echoed the calls from the Joseph Rowntree Foundation, the All-Party Parliamentary Group and many other third sector organisation – for the UK Government to urgently legislate to introduce an Essentials Guarantee.

Reversing the very worst welfare reform changes, the benefit cap, the benefit freeze, and limit the increasing use of benefits sanctions would go some way to moving the value of benefits towards the levels of an Essentials Guarantee and addressing the impacts these reforms have had on poverty levels across the UK.

Impacts on poverty levels

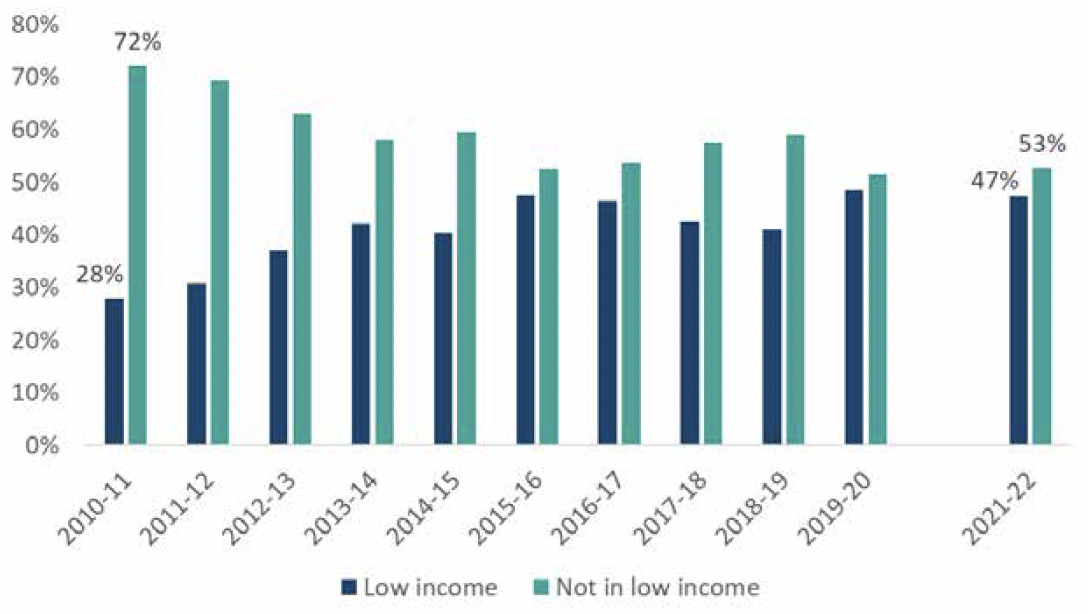

The effects of the UK Government’s policies to reduce the benefit bill have been felt most heavily by the poorest households. The likelihood of being in poverty while being in receipt of these benefits has increased over time. Almost half of households in receipt of Universal Credit, and the legacy benefits it is replacing, were in poverty in 2021-22, compared with around 28% in 2010-11 (see Figure 4).[37]

Note: The proportion of households in receipt of Universal Credit or a legacy benefit in Scotland that fall under the Households Below Average Income (HBAI) median income, after housing costs (AHC). 2020-21 data is not provided – it was not possible to obtain a representative sample due to the Covid pandemic disrupting the data collection in this year.

Source: Stat-Xplore tables: 60 per cent of median net household income (AHC) in latest prices and Universal Credit or Equivalent received by the Family by Financial Year in Scotland by Households.

The adequacy of social security benefits is not the only driver of poverty but, looking at the current levels of poverty in the UK, it is clear that the benefit system is failing those who need it most.

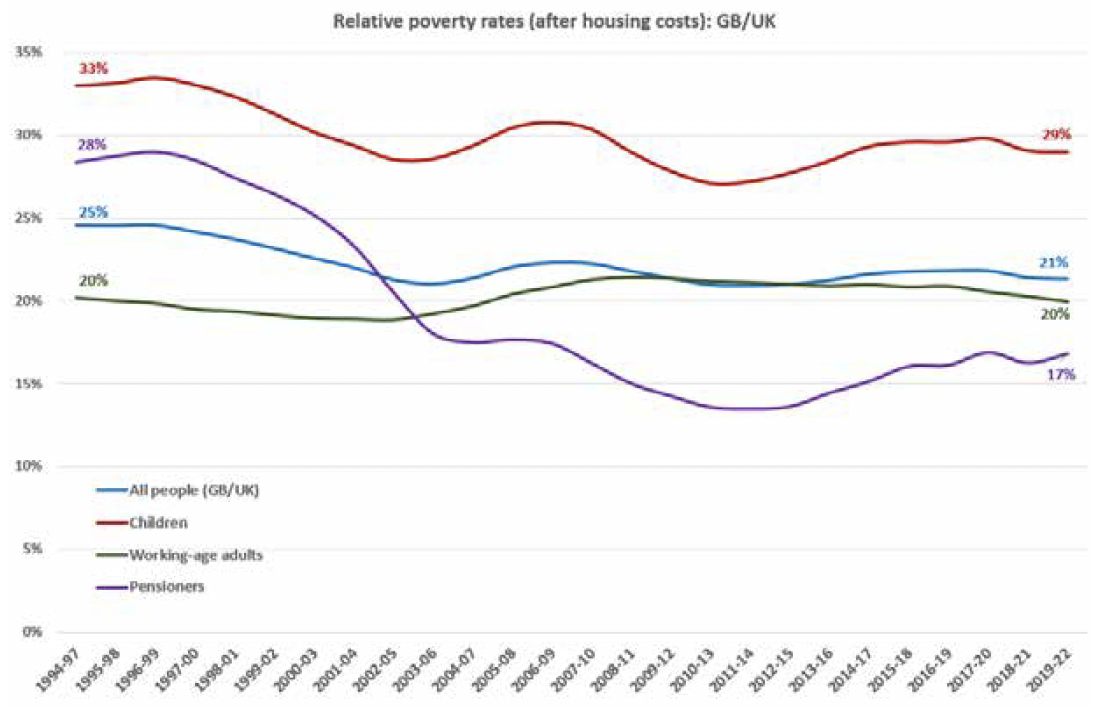

Poverty can be defined in a number of ways, but a key measure is relative poverty after housing costs (AHC).[38] In 2021-22, 14.4 million people were estimated to live in relative poverty (22%) across the UK. Of these, 8.1 million were working-age adults (20% poverty rate), 4.2 million were children (29% poverty rate), and 2.1 million were pensioners (18% poverty rate) – see Figure 5.[39], [40]

Note: Family Resources Survey (FRS) figures are for Great Britain up to 2001/02, and for the United Kingdom from 2002/03. The reference period for FRS figures is single financial years. The figures presented here are three-year averages.

Source: Scottish Government analysis of the Family Resources Survey Poverty and Income Inequality in Scotland 2019-22 (data.gov.scot)

Households below average income: for financial years ending 1995 to 2022 – GOV.UK (www.gov.uk)

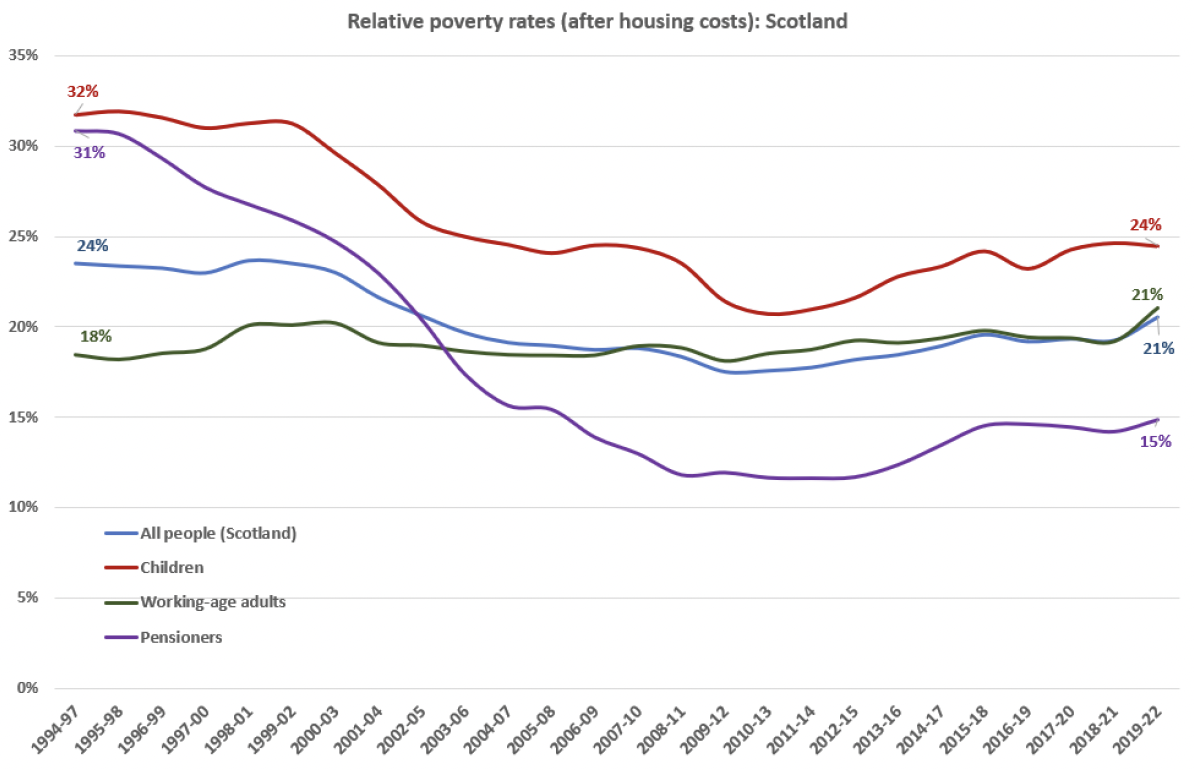

In Scotland, 1.1 million (21%) of the overall population were estimated to be living in relative poverty AHC in 2019-22. Of these, 710,000 were working-age adults (21% poverty rate), around 250,000 (24% poverty rate) were children and around 150,000 (15% poverty rate) were pensioners – see Figure 6.[41]

Source: Scottish Government analysis of the Family Resources Survey Poverty and Income Inequality in Scotland 2019-22 (data.gov.scot)

Households below average income: for financial years ending 1995 to 2022 – GOV.UK (www.gov.uk)

Scottish Government analysis suggests that, if the UK Government reversed key welfare reforms, 70,000 people in Scotland could be lifted out of poverty in 2023-24, including 30,000 children. Disposable income for families with children in poverty would increase by 10%.[42]

The increase in working poverty in recent years has also been significant. In Scotland, 57% of working-age adults in poverty and 69% of children in poverty live in a household where someone is in paid work.[43]

As the Joseph Rowntree Foundation set out, paid work offers a route out of poverty for those of us of working age, but for work to offer protection against poverty, it must offer good pay, enough hours for an adequate wage, and job security.[44]

The Joseph Rowntree Foundation has recently reported that approximately 3.8 million people across the UK experienced destitution in 2022, including around one million children. This is almost two and a half times the total number in 2017 and nearly triple the number of children. The report highlights that ‘after more than a decade of deep benefit cuts and freezes, levels of working-age benefits are now demonstrably inadequate’.[45] By comparison to other regions of the UK, Scotland has experienced by far the lowest increase in destitution since 2019, with the report noting this may be indicative of the growing divergence in welfare benefits policies in Scotland, notably the introduction of the Scottish Child Payment. However, that destitution exists at all is an indictment of Westminster’s social security system.

Under current constitutional arrangements, Scotland has limited levers through which to manage and organise the labour market and ensure that work is well paid and secure. The National Living Wage, which sets the minimum hourly rate at which employees can be paid, is set by the UK Government. Powers over employment rights, including parental leave, the right to strike and rights to minimum hours, breaks and holidays, are also all reserved to the UK. And Westminster has full control of the tax rules that incentivise employers to offer insecure work, as the UK Government’s own review noted.[46]

The UK Government’s Spring Budget Statement this year and accompanying Health and Disability White Paper were presented and framed by the Chancellor as incentivising work. Both put the focus very much back on the individual, setting out ‘support’ to enable sick and disabled people to find and sustain paid employment – essentially putting people at risk of benefit sanctions. Neither the budget statement or the White Paper offered any meaningful changes for employers or to employment law to support people back into or help them maintain paid employment.

In response to the White Paper, Disability Rights UK said:

‘Barriers to more Disabled people getting employment do not lie with Disabled people ourselves but with society – including inaccessible transport, poor employer attitudes, inadequate flexible working and Access to Work Support and failure to make reasonable adjustments.’[47]

Steps to limit or reduce the financial support available to people with ill health and disabilities will surely do nothing to improve poverty rates – the figures already show that disabled people are more likely to experience poverty than the general population.[48] UK-wide, disabled people make up 28% of people in poverty and a further 20% of people in poverty live in a household with a disabled person. This statistic is largely replicated in Scotland where around 410,000 households in poverty (42% of all households in poverty) include a disabled person.[49]

Unpaid carers are also more likely to experience poverty. Even before the impacts of the coronavirus pandemic and the current cost of living crisis, many carers faced precarious financial situations, and 1.2 million informal carers were living in poverty in the UK.[50]

The poverty figures speak volumes, but they cannot fully convey the very real human cost these decisions by the UK Government continue to have on individuals and families. The physical and mental harms that come from living on a low, insecure income can stop people from living up to their potential, and living a full, long life. Addressing poverty is one of the Scottish Government's national missions – not just because it is the right thing to do, but because lifting people out of poverty and preventing them from falling into poverty in the first place, has long-term benefits for society and public services. We know that children who grow up in poverty are less likely to do well at school or go on to higher or further education. By moving children out of poverty and helping them to realise their full potential, we can reduce the risk of them becoming the parents of children in poverty in the future.

Living in poverty, even for short periods, increases the risk of illness and disease, impacting on people’s ability to get themselves out of poverty through accessing paid work, and increasing reliance on health and social care services. Reducing poverty will help to reduce health inequalities.

Ultimately, there is evidence that living in poverty reduces life expectancy. A review by the Glasgow Centre for Population Health and the University of Glasgow cited a range of evidence linking the UK Government’s austerity programme, which included the reforms discussed above, to approximately 335,000 additional deaths across the UK:

‘There is clear evidence of adverse changes to mortality rates in the UK from the early 2010s onwards: a slow-down in the rate of improvement overall, alongside increasing death rates among more socioeconomically deprived populations; inequalities have widened considerably as a consequence of the latter. These changes predate the Covid-19 pandemic and are important context for understanding the scale of pandemic- related inequalities. Although a number of different contributory factors were initially proposed, a considerable body of evidence now demonstrates that UK Government’s "austerity" policies are the main cause of these pre-pandemic changes.’[51]

The report concludes that there is growing evidence of deeply worrying changes to mortality trends in the UK – particularly among more socio-economically deprived populations – which have been largely attributed to UK Government policy.

The links between social security and the economy

The case for reform of the UK social security system – and Universal Credit in particular – is often made on the basis of fairness and social justice. The economic case is less often made but is no less compelling. A strong social security system which works for everyone, at all life stages, should be integral to a wellbeing economy.

Social security is, in many ways, a driver of the labour market and the broader economy.[52] When it works well, as in the Nordic countries, it provides people with security and choice throughout their working lives. It is a genuine safety net.

This means that when people lose their jobs, or temporarily leave the labour market to start a family, provide care, or because of ill-health or disability, they have enough income from benefits that they do not have to accept the first job they find. It can only be of benefit to the economy – and to the employer and the individual – if employees are well-matched to jobs that suits the skills they have.

Similarly, when people want to invest in a business idea or set up a new enterprise, they can be sure that if the risk does not pay off, they will still get support to move into employment, retrain or establish another business, without being pulled into poverty.

The UK social security system does not work this way. Losing a job, being unable to work or having to close a business is difficult for anyone in any country, but in the UK, social security can be seen as a barrier to help rather than an enabler.

This perception of barriers is, at least in part, why some people choose not to apply for benefits. At the start of the pandemic, for example, researchers from the ‘Welfare – at a Social Distance’ project reported that around half a million people who were eligible for Universal Credit did not claim it.[53] Of these, 220,000 thought they were eligible for UC but did not want to claim for a number of reasons, including:

- 41% ‘didn’t think it would be worth the hassle’

- 32% ‘didn’t want to be forced to do things by sanctions’

- 27% didn’t want to be ‘the kind of person who claims benefits’

- 22% said they were ‘struggling, but thought things would get better soon’

The researchers also estimated that another 280,000–390,000 people wrongly thought they were ineligible for Universal Credit so did not apply. If perceived stigma, complexity and bureaucracy can deter people from applying for social security, it is not a safety net for everyone. It is rather a welfare service for those who have no other choice.

Those who do apply may find that benefit levels are inadequate. Research by Joseph Rowntree Foundation and the Trussell Trust found that the basic Universal Credit level was at its lowest level ever in 2023-24, as a proportion of average earnings, and did not provide enough to meet essential needs.[54]

This is crucial in economic terms because inadequate incomes can move people further from the labour market.[55] This may be particularly problematic when:

- the mental strain of having to deal with debt or housing arrears, feed a family or fund basic essentials, deters people from being able to look for work or take on new employment. As the All-Party Parliamentary Group on Poverty at Westminster noted recently, ‘Living in scarcity does not put people in the right mindset to start looking for work’[56]

- the volatility of household incomes under Universal Credit, particularly for couples who are both in work, leads some employees, particularly women, to reduce their hours or quit their jobs so that household incomes are more stable[57]

- the difficulties of claiming childcare costs as part of Universal Credit lead some parents to reduce the hours they work so they can care for their children themselves[58]

- people struggle to meet the costs associated with looking for work or moving into a new career: for example, ‘needing to pay for accreditation in construction, or registration and a criminal reference check to be a child minder, or insurance to be a taxi driver’[59]

A new approach to social security is needed that provides people with an adequate income when they are not able to work, lose their jobs or when their business fails; a system that supports people to retrain and to find fair, flexible work; that supports employers to make reasonable adjustments to retain staff. A new system needs to make accessing support for childcare costs easy. Stigma within the system – and within society about social security – needs to be addressed: there should be no shame in using social security.

This needs to be supported by fair employment practices, as described in the ‘Building a New Scotland: A stronger economy with independence’ which could include a fair national minimum wage, access to flexible working, higher minimum standards of sick pay and parental leave,[60] and wider family-friendly policies such as access to early learning and childcare and training, rehabilitation, and supported employment to support disabled people into work. These measures could go hand in hand with social security to support people as they transition through life’s ups and downs.

A successful model would be one which provides integrated, person-focused support to breakdown barriers to employment for those who are able to work – and provides adequate levels of support for those who are not able to undertake paid work.

This government believes that this model of social security can best be delivered in Scotland via independence. How Scotland has begun to use its own social security powers shows what might be possible.

Contact

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback