Student Finance and Wellbeing Study (SFWS) Scotland 2023-2024: main report

Student Finance and Wellbeing Study Scotland for academic year 2023 to 2024 explores student’s financial experiences whilst studying at college and university in Scotland.

9. Experiences of financial difficulty

Students in the survey were asked, 'Would you say that you have faced financial difficulties during your current course?', with answer options 'yes' or 'no'. Students were then asked, 'Which of these, if any, are you doing because of financial difficulties you are experiencing?'. A list of 16 possible actions was provided and students were asked to select all that applied. In the focus groups and interviews, students were also asked about their financial experiences and any action they take to get by.

The data for each study level and students from under-represented groups are discussed below.

9.1. Key findings

- Whilst some students reported that they were not experiencing financial difficulty, financial difficulty was greatest amongst students from under-represented groups where two-thirds (66%) of students reported that they had experienced financial difficulty. Around half of HN/undergraduate (56%) and postgraduate (50%) students, and three-fifths of FE students (61%) reported experiencing financial difficulty during their current course.

- Across all study levels and students from under-represented groups, some subgroups were more likely to experience financial difficulty: females; students aged over 25; students whose parents had no experience of HE; and students in the 20% most deprived areas.

- Spending less on non-essentials, spending less on food shopping and essentials, cutting back on non-essential journeys, using less fuel such as gas or electricity in their home, and using savings were common actions all student groups took as a result of facing financial difficulties. This was reiterated in the qualitative research which found that to ensure they could afford essential payments, students reduced their spending on energy, travel, food and social activities with family and friends. Some had used foodbanks or did not turn on their heating, including during winter.

- Around 1 in 10 of both FE students and students from under-represented backgrounds (15% and 11% respectively), and 1 in 20 HN/undergraduate (6%) and postgraduate (5%) students said they used support from food banks because of financial difficulties.

- Around 1 in 20 FE (4%), HN/undergraduate (6%), postgraduate (4%) students and students from under-represented groups (6%) gambled or invested to make money as a result of financial difficulties.

9.2. FE students and financial difficulty

Around three-fifths (61%) of FE students reported facing financial difficulties during their current course, with a higher proportion of female (65%) than male (54%) students facing difficulties. FE students aged 20 and over (aged 20 to 24 (67%) and 25 and over (68%)) were more likely than students aged 16 to 19 (53%) to report facing financial difficulties while studying.

Around 7 in 10 FE students whose parents had no experience of HE (69%) had faced financial difficulties compared with 56% of those with parents with HE experience. Similarly, around 7 in 10 (69%) FE students from the 20% most deprived areas faced financial difficulty, as did 69% of those living independently (renting or with a mortgage) compared with 57% of students from the 80% least deprived areas and 51% of those living with their parents.

9.2.1. Impact of financial difficulties for FE students

The proportion of FE students who reported taking each of the 16 potential actions because of financial difficulties are presented in Table 9.1. The most common actions FE students took due to financial difficulties were:

- spending less on food shopping and essentials (52%),

- spending less on non-essentials (49%),

- skipping meals (47%).

Only a small proportion of FE students said they used support from food banks (15%) and/or charities (8%) and/or gambled or invested to make money (4%) because of financial difficulties.

Table 9.1: Changes FE students have made due to financial hardship

Response |

Total (%) |

|---|---|

Spending less on food shopping and essentials |

52 |

Spending less on non-essentials |

49 |

Skipping meals |

47 |

Cutting back on non-essential journeys |

40 |

Using less fuel such as gas or electricity in my home |

36 |

Buying more second-hand clothing, electronic and household goods (including computers, other electronic equipment) |

36 |

Using my savings |

28 |

Shopping around more |

21 |

Making energy efficiency improvements to my home |

20 |

Using credit more than usual, for example, credit cards, buy now pay later, loans or overdrafts to purchase essentials |

20 |

Not getting or renewing a TV license |

18 |

Sold personal possessions |

18 |

Increased paid working hours |

17 |

Using support from food banks |

15 |

Using support from charities |

8 |

Gambled or invested to make money (e.g.in a betting shop/online or investing in the stock market or cryptocurrency) |

4 |

Doing other things |

3 |

Unweighted base |

282 |

This table presents the changes students have made due to financial hardship from the most commonly selected to the least commonly selected.

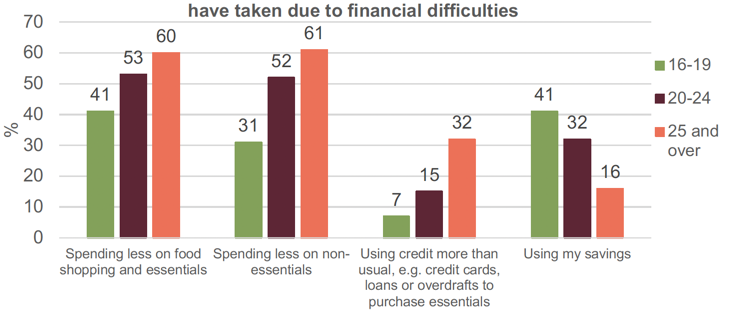

Overall, FE students aged 25 and over were more likely than those aged 24 and under to report that they engaged in behavioural changes due to financial difficulties. Some key examples of this are shown in in Figure 9.1. For example, those aged 25 and over were more likely to say they were spending less on food shopping and essentials (60%) and spending less on non-essentials (61%) than those aged 16 to 19 (41% and 31% respectively). An exception was for use of savings where those aged 16 to 19 were more likely to use their savings due to financial difficulties (41%) than those aged 25 and over (16%).

Behavioural changes due to financial difficulties did not differ by sex, with a few exceptions. Female FE students were more likely to buy more second-hand items (40%), use support from food banks (19%) and from charities (11%), than male FE students (24%, 6% and 4% respectively).

Those living independently (renting or with a mortgage) were more likely than those living with their parents to have taken the actions listed due to financial difficulties, with the following exceptions.

Those living with their parents were more likely to have used their savings than those living independently (renting or with a mortgage) (40% and 18%, respectively), but there were no significant differences in the proportions who skipped meals, increased paid working hours, sold their possessions, or gambled or invested to make money.

Finally behavioural changes due to financial difficulties varied significantly by area deprivation for FE students in two instances. Those from the 20% most deprived areas were more likely to skip meals (55%) and use support from charities (14%) than those from the 80% least deprived areas (44% and 6% respectively).

9.3. HN/undergraduate students and financial difficulty

Over half (56%) of HN/undergraduate students reported facing financial difficulties during their current course, which was slightly less than the 61% for FE students.

Certain groups were more likely to face financial difficulty than others, with patterns similar to those seen among FE students. HN/undergraduate students most likely to report experiencing financial difficulties during their current course were:

- Female students (59%, compared with males, 49%)

- Students aged 25 and over (67%, compared with 42% of those aged 16 to 19)

- Students whose parents had no HE experience (65%, compared with 49% of those with parents with HE experience)

- Students living independently (renting or with a mortgage) (61%, compared with 44% of those living with their parents)

- Students from the 20% most deprived areas (65%, compared with those from the 80% least deprived areas, 52%).

9.3.1. Impact of financial difficulties

The most common actions HN/undergraduate students reported taking as a result of financial difficulties were spending less on non-essentials (68%), spending less on food shopping and essentials (60%), cutting back on non-essential journeys (49%), and using their savings (48%) – the first two were also actions most often reported by FE students albeit in the reverse order.

Furthermore, around 3 to 4 in 10 students reported that because of financial difficulties they were:

- Using less fuel such as gas or electricity in their home (42%)

- Buying more second-hand clothing, electronic and household goods (41%)

- Increasing their paid working hours (36%)

- Shopping around more (34%)

- Skipping meals (32%).

As with FE students, only a small proportion of HN/undergraduate students said they used support from food banks (6%), support from charities (4%) or gambled or invested to make money (6%) because of financial difficulties.

Overall, students aged 25 and over were more likely than those aged under 25 to have taken any of the 11 actions in the question. For example:

- around two-thirds (67%) of those aged 25 and over had spent less on food, compared with around half (52%) of those aged 16 to 19, and around 4 in 10 (42%) had used credit compared with around 1 in 10 (11%) of those aged 16 to 19.

- those aged under 25 were more likely to have used their savings (50%, compared with 38% of those aged 16 to 19) and to have increased their paid working hours (43% of those aged 20 to 24, compared with 30% of those aged 25 and over).

HN/undergraduate students living independently (renting or with a mortgage) were more likely than those living with their parents to have taken actions due to financial difficulties, with the following exceptions:

- there were no significant differences between those living independently (renting or with a mortgage) and those living with their parents in the proportions who had used their savings, or gambled or invested to make money.

Where there were differences by area deprivation, those from the 20% most deprived areas were more likely than those from the 80% least deprived areas to report behavioural changes due to financial difficulties. For example:

- around 4 in 10 of those from the 20% most deprived areas had skipped meals (42%) or had used credit more than usual (38%), compared with those from the 80% most deprived areas (30% and 25% respectively).

- overall, 6% of HN/undergraduate students had used support from food banks, however 13% of those from the 20% most deprived areas had done so, compared with 4% of those from the 80% least deprived areas.

There were no clear pattern of statistically significant differences by sex, part-time and full-time status and parental experience of HE. For example:

- Female students were more likely than male students to: cut back on spending on food shopping; buy more second-hand goods; increase their paid working hours; and use their savings. For example, around 4 in 10 (39%) female students said they had increased their paid working hours due to financial difficulties compared with around 3 in 10 (31%) of male students. While male students (15%) were more likely to have gambled or invested to make money than female students (3%) due to financial difficulties.

- Part-time HN/undergraduate students were more likely to report shopping around more (48%) and using credit more than usual (39%) compared with full-time students (31% and 24% respectively). Full-time students were more likely than part-time students to report skipping meals (34% compared with 24%), and increasing paid working hours (39% compared with 25%).

The actions taken due to financial difficulties did not vary by parental experience of HE, with a few exceptions. Students whose parents had no HE experience were more likely to have cut back on non-essential journeys (56%) and used credit more than usual (34%) than those whose parents had HE experience (44% and 22% respectively).

9.4. Postgraduate students and experiences of financial difficulty

Half (50%) of postgraduate students had faced financial difficulties during their current course.

As with FE and HN/undergraduate students, postgraduate students whose parents had no HE experience were also more likely (58%) than those with parents with HE experience (46%) to have faced financial difficulties. Two-thirds (67%) of postgraduate students from the 20% most deprived areas reported financial difficulties during their course compared with less than half (47%) of those from the 80% least deprived areas. There were no significant differences by age and sex.

9.4.1. Impact of financial difficulties

The most common actions postgraduate students had taken due to financial difficulties were spending less on non-essentials (79%), spending less on food shopping and essentials (63%), using less fuel such as gas or electricity in the home (59%), cutting back on non-essential journeys (57%), and using their savings (55%).

Furthermore, between a third and a half of postgraduate students reported that due to financial difficulties they were:

- Buying more second-hand clothing, electronic and household goods (52%)

- Shopping around more (49%)

- Using credit more than usual (38%)

- Increasing paid working hours (34%).

A smaller proportion of postgraduate students said they were skipping meals (25%) as a result of financial difficulties than FE (47%) and HN/undergraduate students (32%).

As with FE and HN/undergraduate students only a small proportion of postgraduate students said they used support from food banks (5%), support from charities (4%) or gambled or invested to make money (4%) as a result of financial difficulties.

Postgraduate students aged 20 to 24 were more likely to have used their savings due to financial difficulties (66%) compared with those aged 25 and over (51%). Female postgraduate students were more likely than male students to have sold possessions (32% and 16%, respectively). Those who lived independently were more likely than those living with their parents to be using less fuel in their home (64% and 29%, respectively) and conversely, those living with their parents were more likely to be cutting back on non-essential travel than those living independently (70% and 55%, respectively). There was variation by parental HE experience on one count; postgraduate students whose parents had no HE experience were more likely to use credit more often than usual (46%) than those with parental HE experience (33%).

Overall, behavioural changes due to financial difficulties did not vary by area deprivation.

9.5. Students from under-represented groups

The highest proportion of students in this study reporting they had experienced financial difficulties were students from under-represented groups, with two-thirds (66%) facing difficulties during their current course.

Students from under-represented groups who were more likely to report that they faced financial difficulties during their current course were:

- Female students (68%, compared with male students, 62%)

- Students aged 25 and over (71%, compared with those aged 20 to 24 (63%), and those aged 16 to 19 (59%)

- Students whose parents had no HE experience (75%, compared with those with parents with HE experience, 59%)

- Students living independently (renting or with a mortgage) (70%, compared with 55% of those living with their parents)

- Students from the 20% most deprived areas (77%, compared with those from the 80% least deprived areas, 63%).

9.5.1. Impact of financial difficulties

The most common actions students from under-represented groups took due to facing financial difficulties were spending less on non-essentials (66%), spending less on food shopping and essentials (65%), and cutting back on non-essential journeys (52%).

Furthermore, between 30% and 48% of students reported that due to financial difficulties they were:

- Buying more second-hand clothing, electronic and household goods (48%)

- Using less fuel such as gas or electricity in their home (46%)

- Skipping meals (41%)

- Using savings (41%)

- Shopping around more (37%)

- Using credit more than usual, for example, credit cards, buy now pay later, loans or overdrafts to purchase essentials (32%)

- Increasing paid working hours (30%).

As with all other student groups, only a small proportion of students from under-represented groups said they were using support from food banks (11%), support from charities (8%), or gambled or invested to make money (6%) as a result of financial difficulties.

Overall, behavioural changes due to financial difficulties varied significantly by age, with students aged 25 and over more likely to adopt these approaches. Exceptions to this were that students aged 16 to 19 were more likely to skip meals (49%) and use their savings (52%) than those aged 25 and over (37% and 33% respectively). There were no significant differences by age for use of food banks, selling personal possessions, or gambling or investing to make money.

Generally, behavioural changes due to financial difficulties did not vary significantly by sex, with a few exceptions. For example, female students were more likely to buy more second-hand items (50%) than male peers (40%). Conversely, male students were more likely to gamble or invest to make money (13%) than female peers (4%).

As for FE and HN/undergraduates, students from under-represented groups who lived independently (renting or with a mortgage) were more likely than those living with their parents to have taken the actions listed due to financial difficulties. The exceptions to this were that there were no significant differences in the proportions using their savings, selling their possession, or gambling or investing to make money.

There were some notable variations by area deprivation. Students from the 20% most deprived areas were more likely to spend less on food shopping (68%), skip meals (52%), use support from food banks (18%) and use support from charities (13%), than those from the 80% least deprived areas (64%, 38%, 9%, 5% respectively).

There was no clear pattern of variations by parental HE experiences.

9.6. How students navigated financial difficulties

From the survey data, it is clear that students took a number of actions as a result of the financial difficulties they were experiencing, some of which were explored further in the qualitative research.

As outlined in section 15 below, for a proportion of students the income they received from various sources of income was insufficient to cover their expenses while studying. This was being exacerbated by the cost of living crisis and increased cost of food, utilities and petrol, with no or limited increases to funding.

"It's just not great, it's not healthy to be living month by month. At the moment I think I've literally got £10 in my account and that is until the end of the month." (Student parent focus group)"

Students took a number of steps to navigate their way through challenging financial times, which are discussed below.

9.6.1. Choosing to make changes to spending

To ensure they had enough money to pay for essentials such as accommodation costs, utility bills and food, there were students who reduced, or cut out completely, spending on social activities with family and friends. Examples included not spending money on holidays, reducing spending on presents at Christmas and birthdays, and reducing social activities such as eating out or going for coffee. The extent to which spending on social activities were reduced varied.

There were also students who made changes to their behaviour to reduce expenses so they could live within their means. To reduce travel costs, particularly in light of petrol price increases, students took a number of actions including opting for public transport or walking where possible instead of taking their car, or cutting back on non-essential journeys. One student gave up their car because they could not afford to run it while they were studying. There were students who had access to a free bus pass through the Scottish Government's free bus pass scheme for under 22s and those with a disability, which helped them to save on costs. However, there were students who could not make travel cost savings because they lived too far away from the university or college to walk, and they did not have access to reliable public transport. As outlined in Chapter 15 there were students who were forced to miss class if they could not afford to travel.

To reduce food costs students stated that they shopped around or chose cheaper brands to make their money go further. Students also cut back on ready meals, takeaway food and drink and instead took packed lunches or batch cooked to save money.

"This is a small thing, but when I'm buying like juice or water or stuff, just looking about how much pence per litre it costs […] that applies to all food and all drink. I think also maybe not just going to Tesco, Asda, Morrisons. Shop around. Do you know what I mean? Go to Lidl and Aldi. Go to the corner shop. […] It's about being a bit more savvy and finding those things that are a bit cheaper for - or going in when there's deals on. It's just as simple as that. (Part-time HNC/HND student)"

Students also tried to cut back on other costs such as gas and electricity by using smart meters to track spending, and stopping or reducing the purchase of clothes. Some students, being mindful of energy usage, also sold some possessions, sought to increase their incomes or shopped around for cheaper food.

Overall, it was difficult for students to save money on course costs as, for example, it was essential to purchase some equipment for the course work.

9.6.2. Enforced changes to spending

There were students across study levels and under-represented groups whose financial situation was more difficult to navigate as there was a bigger gap between their income and expenses. These students were taking more severe actions to try and make their income cover their expenses. This included cutting back on essentials such as food, heating (including during winter) and clothing. Students described eating less, missing meals and avoiding heating their accommodation to try and save money. There were also students who accessed support from charities and food banks to enable them to eat and pay for utilities.

"We contacted Scarf. Scarf it's a charity that helps with gas and electric, they'll find you a cheaper company, it was them that told us really to go for like pay monthly not pay as you go it's a rip off. They provided a voucher for…because we were out of electric, like 2p left on our electric meter and that was on emergency and none of us got paid until the following week. They gave us a voucher to put into the electric to keep us going until then and we didn't have to pay it back. […] My sister she used them once and she told me about them. I thought it was a scam at first, I thought nah naebody is going to give you…naebody is away to give you money for your gas and electric [….] but you think just try it. […] They do everything, they give you advice on gas and electric, they'll help you, come out and see you, help you figure out whether your rates are right. They'll help you switch if you're on too high a thing and they've found a cheaper one they'll help you switch. So it's brilliant. (Full-time FE student parent)"

As mentioned in Chapter 8, there were students that had to borrow money or use credit in order to pay for their expenses. Students used credit cards, took out a range of different types of loans, accessed their overdraft facility and borrowed from friends and family to help them pay their bills. While some students were able to pay back the money they borrowed, others said they went into debt each month due to rising costs of food, utilities and petrol.

Contact

Email: socialresearch@gov.scot

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback