Student Finance and Wellbeing Study (SFWS) Scotland 2023-2024: main report

Student Finance and Wellbeing Study Scotland for academic year 2023 to 2024 explores student’s financial experiences whilst studying at college and university in Scotland.

7. Expenditure

7.1. Introduction

Students were asked about a range of different types of expenditure in the survey. This was then used to calculated expenditure for the academic year 2023 to 2024. The questionnaire covered four key areas of expenditure: participation costs, living costs, housing costs and spending on children:

- Participation costs include expenditure on books, stationery, computer equipment and accessories, and any special equipment or trips associated with course work. Costs associated with tuition fees are not included, as these are reported separately in Chapter 4.

- Living costs include expenditure on food and drink, personal entertainment, household goods and non-course travel.

- Housing costs include mortgage and rent costs, retainer costs, household bills (including fuel costs and council tax) and other housing costs (such as household insurance).

- Spending on children includes the purchase of items such as toys, clothes, school uniforms, entertainment, presents, nappies and baby equipment, school lunches, school trips, school fees, and childcare costs, such as nurseries, childminders, school aftercare fees, travel and babysitters.

For all students, annual estimates were calculated by multiplying weekly totals by the number of weeks in an academic year (39), with monthly totals first being converted to weekly totals. Estimates of expenditure for students who shared joint financial responsibility for housing costs or other essential expenditure with a partner have been adjusted, where that expenditure was judged to be joint rather than individual.

7.2. Key findings

The median total expenditure was:

- £7,723 for FE students

- £8,883 for HN/undergraduate students

- £10,558 for postgraduate students

- £10,525 for students from under-represented groups

- Housing costs were the highest category of expenditure for all but FE students, representing around half of the median total expenditure for HN/undergraduates, postgraduates and students from under-represented groups.

- The median spend on housing was the same for HN/undergraduate students and students from under-represented groups (£4,900), was £4,250 for FE and £5,213 for postgraduate students.

- Fuel costs represented around a quarter (24%) of mean housing costs for postgraduate students, rising to a third (33%) of mean housing costs for FE students.

- Living costs were the highest category of spend for FE students, representing over half (54%) of their mean total expenditure, with food purchases making up 72% of their mean living costs.

- The median spend on living costs was similar for FE students (£3,803) and students from under-represented groups (£3,811). It was £3,542 for HN/undergraduate students, and £4,190 for postgraduate students.

- The qualitative research highlighted how students' biggest spends varied by their personal circumstances, and participants discussed the impact of the cost of living crisis on their spending.

- Course related costs and those associated with course placements further contributed to the financial strain caused by unpaid placements.

- In the interviews and focus groups, students highlighted the high cost of rent and the lack of appropriate student accommodation. This was more sharply felt by participants who were estranged and care experienced students.

- Living at home allowed students to reduce their costs but some were travelling long distances to their college or university.

7.3. Expenditure for FE students

7.3.1. Total expenditure

The median amount of total expenditure for all FE students who incurred expenses was £7,723 for the 2023 to 2024 academic year. The median total expenditure was:

- £8,812 for female students compared with £6,550 for male students.

- £10,870 for those aged 25 and over compared with £3,750 for those aged 16 to 19.

- Similar for those from the 20% most deprived areas compared with those from the 80% least deprived areas (£7,131 and £7,405, respectively).

- £10,588 for those who lived independently (renting or with a mortgage) compared with £3,509 for those living with their parents.

7.3.2. Living costs

Living costs were incurred by nearly all FE students (98%) and represented the highest category of expenditure for FE students, at 54% of their total mean expenditure. The median amount spent on living costs was £3,803 across all FE students.

- Expenditure on living costs was similar for female and male students, but those aged 25 and over spent a median amount of £4,783 compared with £2,235 for those aged 16 to 19.

- Similarly, those who lived independently (renting or with a mortgage) had a median spend on living costs of £4,336 compared with £2,235 of those living with their parents. There were no differences by area deprivation.

By far the highest expenditure within living costs was on food, with this representing 72% of their mean expenditure on living costs. This included grocery bills, eating out and takeaway spending.

- The median amount spent on food by FE students was £2,496, with those aged 25 and over having a median spend of £3,105 compared with a median spend of £1,800 for those aged 16 to 19.

- Those living independently had a median spend of £2,715 with those living with their parents having a median spend of £1,950.

7.3.3. Housing costs

Housing costs were incurred by around three-quarters (74%) of all FE students but represented the second highest category of expenditure among those who it applied to, at 43% of their total mean expenditure. Overall, the median spend on housing costs among all FE students was £4,250.

The median spend on housing costs for FE students was:

- £4,500 for female students compared with £3,297 for male students.

- £5,165 for those aged 25 and over compared with £2,250 for those aged 16 to 19.

- £3,297 for those from the 20% most deprived areas compared with £4,755 for those from the 80% least deprived areas.

- £5,246 for those living independently compared with £2,000 for those living with their parents.

Fuel made up 33% of the mean spend on housing costs for FE students. The median spend on fuel was £1,260, with female students spending £1,350 and male students £1,080 on fuel. Those from the 20% most deprived areas had a median spend of £1,300 on fuel, compared with £1,116 for those from the 80% least deprived areas.

7.3.4. Course related costs

Course related costs were considerably lower than both living and housing costs for FE students, with a median spend of £250 in the academic year 2023 to 2024 among the 72% of FE students who incurred any course related expenditure.

Students aged 25 and over, those from the 20% most deprived areas and those living independently had a median spend on course-related items of £350, compared with a median spend of £100 for those aged 16 to 19, £200 for those from the 80% least deprived areas, and £100 for those living with their parents.

7.3.5. Spending on children

A quarter (25%) of FE students reported spending on children with a median spend of £2,225. The vast majority of these students were female (92% compared with 8% who were male students) and aged 25 and over (93% compared with 7% who were aged under 25).

7.4. Expenditure for HN/undergraduate students

7.4.1. Total expenditure

The median total expenditure for all HN/undergraduate students was £8,883, compared with £3,803 reported by FE students. Male students' median spend was £9,070 and for female students it was £8,883. The median total expenditure was:

- £11,071 for those aged 25 and over compared with £7,979 for those aged 20 to 24, and £7,506 for those aged 16 to 19.

- £10,015 for those who lived independently (renting or with a mortgage) compared with £5,145 for those living with their parents.

- £9,400 for those from the 20% most deprived areas compared with £8,849 for those from the 80% least deprived areas.

- £8,530 for full-time HN/undergraduate students compared with £10,311 for part-time students.

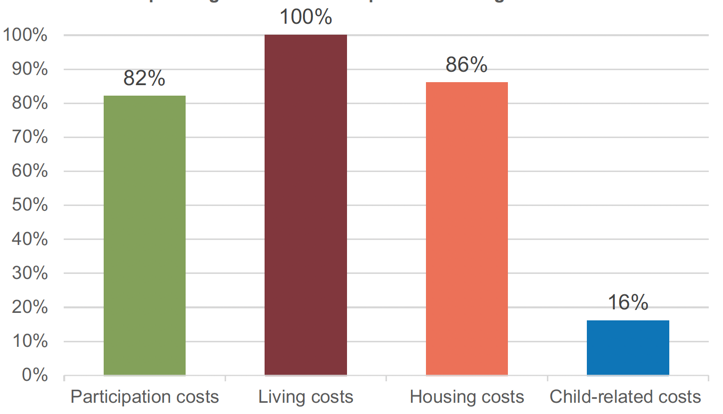

Figure 7.2 shows the proportion of HN/undergraduates who incurred various types of expenditure. The median amount spent on each of these different types of expenditure and differences among sub-groups are explored within the sub-sections below.

7.4.2. Living costs

All HN/undergraduate students incurred living costs but this was not the highest category of expenditure, as was the case with FE students, but their second highest, at 45% of their total mean expenditure. The median spend on living costs for HN/undergraduate students was £3,542.

- Part-time students had a median spend of £4,407 on living costs, compared with full-time students (£3,378).

- The median spend increased with age, with those aged 16 to 19 having a median spend on living costs of £2,955 compared with £4,163 for those aged 25 and over.

Median spending on food was £2,310 with a lower median among those aged 16 to 19 (£1,920) and full-time students (£2,175) compared with those aged 25 and over (£2,580) and part-time students (£2,730). There was no difference in the median spend on food by area deprivation or whether students lived with their parents or independently.

7.4.3. Housing costs

Housing costs represented the highest category of expenditure at 54% of total mean expenditure, with a higher proportion of HN/undergraduate students (86%) incurring housing costs compared with FE students (74%). Among those who incurred housing costs, the median spend was £4,900.

The median spend on housing costs for HN/undergraduate students was:

- £5,400 for students aged 16 to 19, compared with £4,854 for those aged 25 and over.

- £4,353 for those from the 20% most deprived areas compared with £4,996 for those from the 80% least deprived areas.

Unsurprisingly, those students living at home only had a median housing spend of £1,800 compared with £5,260 for those living independently. Median housing expenditure was similar for male and female students and for full-time and part-time students.

Fuel costs for electricity and fuel bills made up 26% of the mean spend on housing for HN/undergraduate students. The median spend on fuel for HN/undergraduate students was £1,080 per academic year and was:

- £1,500 for full-time students, and £975 for part-time students.

- £1,170 for female students compared with £946 for male students.

- £1,463 for those aged 25 and over compared with £720 for those aged under 25.

- There were no differences by area deprivation or whether students lived independently or with their parents.

7.4.4. Course related costs

Around 8 in 10 (82%) of HN/undergraduate students reported incurring course related costs, with a median amount of £350, higher than that reported for FE students.

- Male students had a median spend on course related costs of £430 compared with £350 for female students.

- Full-time students had a median spend of £350 compared with £300 among part-time students.

- Those from the 20% most deprived areas had a median spend of £420 compared with £320 for those from the 80% least deprived areas.

- There was no clear pattern for differences by age.

7.4.5. Spending on children

Around 1 in 6 (16%) HN/undergraduate students reported spending on children, with a median spend of £2,204, similar to that of FE students. Part-time students were considerably more likely than full-time students to spend on children (33% compared with 12%, respectively), although the median amount of spending was similar (£2,204 and £2,220, respectively).

Over 8 in 10 (83%) HN/undergraduate students reporting spend on children were female (compared with 17% who were male students) and 97% were aged 25 or over, with 3% aged 24 or under. Those from the 20% most deprived areas were more likely (22%) than those from the 80% least deprived areas (16%) to have incurred spending on children with a median spend of £2,400 and £2,085, respectively.

7.5. Expenditure for postgraduate students

7.5.1. Total expenditure

The median total expenditure for postgraduate students was £10,558.

- Those aged 25 and over reported a median total expenditure of £11,176 compared with £9,562 for those aged 20 to 24.

- Median total expenditure was similar for male and female students and those from the 20% most deprived and the 80% least deprived areas.

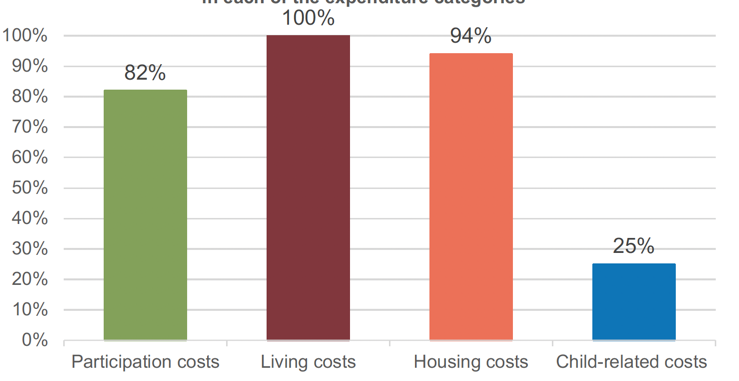

Figure 7.3 shows the proportion of postgraduates who incurred various types of expenditure. The median amount spent on each of these different types of expenditure and differences among sub-groups are explored within the sub-sections below.

7.5.2. Living costs

Median living costs was the second highest expenditure category for postgraduate students, as it was for HN/undergraduate students, incurred by all students and representing 43% of their total mean expenditure. The median spend on living costs was £4,190.

The median spend on living costs for postgraduate students was:

- £4,890 for male students compared with £3,985 for female postgraduate students.

- £3,658 for those from the 20% most deprived areas, compared with £4,340 for those from the 80% least deprived areas.

There was no difference in the median spend on living costs by age, or whether the students were living with their parents or independently.

Median spending on food was £2,288 with male students having a median spend of £2,490 compared with £2,175 for female students. There were no other differences by subgroups.

7.5.3. Housing costs

Housing costs represented the highest category of expenditure at 49% of total mean expenditure, with a higher proportion of postgraduate students, 94%, incurring housing costs compared with all other student groups. Among those who incurred housing costs, the median spend on housing was £5,213.

The median spend on housing was:

- £5,435 for female students compared with £4,950 for male students.

- £5,387 for those aged 25 and over compared with £4,918 for those aged 20 to 24.

- £4,856 for those from the 20% most deprived areas compared with £5,400 for those from the 80% least deprived areas.

Fuel costs represented 24% of the mean housing costs for postgraduate students, similar to that for HN/undergraduate students. The median spend on fuel was £1,170 and £1,258 for those HN/undergraduate students aged 25 and over, and £810 for those aged 20 to 24. There were no differences in the median fuel spend by sex or area deprivation.

7.5.4. Course related costs

The median spend on course related costs was £300 for postgraduate students, with a median spend of £500 for male students and for those from the 20% most deprived areas, compared with £260 for female students and £250 for those from the 80% least deprived areas.

7.5.5. Spending on children

A quarter (25%) of postgraduate students incurred spending on children, with a median spend of £1,688. Female students had a median spend on children of £1,950 and male students a median spend of £1,318.

7.6. Expenditure for students from under-represented groups

7.6.1. Total expenditure

The median total expenditure for students from under-represented groups was £10,525, similar to that for postgraduate students but higher than both the median total expenditure for FE and HN/undergraduate students.

- Female students had a median total spend of £9,809, compared with £8,495 for male students.

- Students aged 25 and over had a median spend of £11,455, with £8,023 reported for those aged 20 to 24 and £6,166 for those aged 16 to 19.

- Unsurprisingly, those who lived independently (renting or with a mortgage) had a higher median spend, £10,764, compared with those living with their parents, £4,820, following a similar pattern to other student groups.

- There was no difference between the median expenditure for those from the 20% most deprived and the 80% least deprived areas.

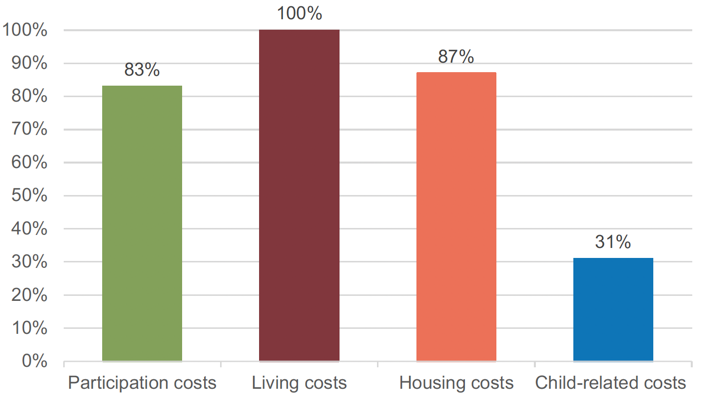

Figure 7.4 shows the proportion of students from under-represented groups who incurred various types of expenditure. The median amount spent on each of these different types of expenditure and differences among sub-groups are explored within the sub-sections below.

7.6.2. Living costs

Median living costs was the second highest expenditure category for students from under-represented groups, similar to HN/undergraduate and postgraduate students. All students from under-represented groups incurred living costs, representing 44% of their total mean expenditure. The median spend on living costs was £3,811.

As age increased, so did the median spend on living costs, with those aged 16 to 19 having a median spend of £2,580, rising to £4,370 for those aged 25 and over. Those living with their parents had a median spend on living costs of £3,014 compared with £3,990 of those living independently (renting or with a mortgage). There was no difference in the median spend on living costs by sex, or area deprivation.

Median spending on food was £2,400, with female students having a median spend of £2,451 compared with £2,340 for male students, and older students having a higher median spend on food (£2,652 for those aged 25 and over) than younger students (£1,773 for those aged 16 to 19). Those living with their parents also had a lower median spend on food (£2,304) compared with those living independently (renting or with a mortgage) at £2,652.

7.6.3. Housing costs

Housing costs were the highest category of spending for students from under-represented groups, representing 51% of the mean total expenditure and incurred by 87% of this group of students. The median spend on housing costs among all students from under-represented groups was £4,860.

The median spend on housing costs was:

- £5,025 for female students compared with £4,608 for male students.

- £5,073 for those aged 25 and over compared with £4,569 for those aged 20 to 24, and £3,882 for those aged 16 to 19.

- £4,410 for those from the 20% most deprived areas compared with £5,100 for those from the 80% least deprived areas.

Fuel costs represented 29% of mean spend on housing for students from under-represented groups. Overall students had a median spend on fuel of £1,300, with female students having a median spend of £1,350 and male students, £1,170. Those aged 25 and over had a median spend of £1,485 compared with £900 for those aged under 25. There were no differences by area deprivation.

7.6.4. Course related costs

The median spend on course related costs was £325 for students from under-represented groups, with a median spend of £429 for male students and £400 for those from the 20% most deprived areas compared with £300 for female students and for those from the 80% least deprived areas. The median spend on course related costs for those living independently (renting or with a mortgage) was £350 and for those living with their parents was £260.

7.6.5. Spending on children

As the students from under-represented groups included those who were parents, unsurprisingly, 3 in 10 (31%) of this group incurred spending on children, with a median spend on children of £2,175. Those who incurred spending on children, as seen for those at HN/undergraduate study level, were more likely to be female than male (36% of students from under-represented groups with spending on children were female and 17% were male) and aged over 25 (53% compared with 5% aged under 25).

Female students reported a median spend on children of £2,225 compared with £1,555 among male students. Those from the 20% most deprived areas had a median spend of £2,473 compared with a median spend of £2,050 among those from the 80% least deprived areas.

7.7. Student experiences of expenditure

As illustrated by the survey responses, students experience a range of different types of expenditure, with basic living costs such as housing, food and essentials, and bills such as gas and electricity making up the biggest proportion of these costs.

However, it is important to highlight that students' biggest expenditure varied by personal circumstances. For example, the qualitative research identified that accommodation was the biggest expenditure for those in private rented accommodation. However, this was not the case for students who lived with family rent free, owned their property outright, received housing benefit or had their accommodation paid for via their college or university. Travel was one of the biggest expenses for students who had to use a car to commute to college or university, particularly as fuel prices increased. For student parents, costs related to their children, including childcare and increased food and utility costs, were a major expense.

"Mine would be fuel, definitely. About £60 a week, roughly, so just shy of £300 a month sometimes, depending on how much I need to commute up. On top of that, car maintenance, etc. (Postgraduate student focus group)"

"For myself, definitely it is childcare, especially now getting into January, with being placed into placements for part of my first year. My childcare is going to go up quite considerably because I now need to put my little youngest one into nursery more often. Luckily, the eldest is in school, which is great, so that helps but I still have to obviously make those financial payments. My little one's dad has split - over a year-and-a-half ago - and unfortunately with him having to take half of the free [nursery] hours, I only get half of what's what, so I have to make up the best of that. So, it's not like I can entirely live off pretty much what the government give the children to be in education. (Student parent focus group)"

The qualitative research also highlighted the impact of the cost of living crisis on student expenditure and overall financial wellbeing. While the price of food, gas and electricity and fuel prices increased, the students' income stayed the same or did not increase at the same rate. This made it more challenging for students to meet the cost of their expenses with their income. The ways in which students managed their finances, and the impact this had on them, are explored in Chapters 8 to 15.

7.7.1. Student experiences of course related costs

Students experienced a range of different course-related expenses, including the need to buy reading materials and specialist course materials such as safety equipment, art supplies or IT hardware or software. Some of these expenses would last students through the entirety of their course, though students expressed frustration at course costs for materials or equipment that they would only use once. While some costs could be mitigated by, for example, using the library or accessing digital versions instead of buying textbooks, others, such as safety equipment or assessment costs, could not.

"The textbooks are prohibitively expensive. Sort of I think the average I would say would be about £40 per textbook and some modules its recommended that you'll use more than one. So I think…I just borrow my textbooks from the library. There's a fairly decent collection at the library. But people who do sort of want to have access to textbooks anytime they spend a couple of hundred pounds each semester buying them. (Full-time undergraduate student)"

"The course is good but the unexpected expenses it's causing is shocking. […] I didn't take into account when I started college that for assessment, my assessment that need to be done need to be paid for, like haircuts and stuff […] if my client can't pay and I need that assessment rather than, fail I'll have to pay you know. This sounds silly, if it's a cut it's only £8 but that £8 that could go towards food, that £8 could go towards gas and electric. […] It's robbing Peter to pay Paul, a colour is about £12 to £22 depending on what they want. (Full-time FE student parent)"

The ways in which students paid for these expenses varied. In some circumstances, course materials and costs were covered by their college or university, while in others, students had to self-fund using their bursary or loan, money from paid work, or by taking out credit to meet these costs. There were also examples of employers meeting students' course costs, when a student was working full-time and studying part-time.

Course placements

For some of the students, work placements were an essential part of their courses. While students did not have to pay to do these placements, and some were able to access reimbursements for placement costs such as travel from their institution, they did have financial implications. Students stated that these placements were unpaid, and because they were full-time placements, and students did not always know exactly when placements would occur, it was difficult for them to find paid work which could be based around these course commitments. This further contributed to financial stress experienced by students. There were instances where students considered dropping out due to the financial strain caused by unpaid placements. One student decided to change course as they could not afford to do an unpaid placement as part of their original course.

"What I get is pretty much just SAAS and that's it. I don't have any job. I had to give up my job just last month because of a placement coming up. I simply can't do the hours that were required of me because I still don't really know what my hours for placement are yet. I'm pretty much on hold from Monday to Sunday and I can start any time between half-seven until half-six. So, I'm still kindae waiting on the things for that one, so it kindae restricts me on finding a job at the moment. Unfortunately, there's a lot of stress on my husband! So, we're really kindae relying on him as being the breadwinner. (Student parent focus group)"

"When I was considering dropping out, it was because there was not really anything in place that would - It's an unfunded placement but you were expected to work full time and just like, 'How am I meant to do a full-time degree and do this placement that is full time and work as well on the side?' So, that's when I changed to applied social sciences because there wasn't any placement requirement but during that time I considered dropping out and then trying to work out what I would do instead. (Full-time undergraduate estranged student)"

7.7.2. Student experiences of accommodation

As outlined above, often one of the largest costs students had to cover was that of their accommodation. This section explores findings from the qualitative research to consider how finance affected students' experiences of accommodation. It outlines the factors which students stated made meeting their accommodation costs easier and more difficult, as well as the impact of these factors on students and their experiences of accommodation.

Factors which make meeting accommodation costs easier

Students discussed the factors which made meeting the costs of their accommodation easier. These included financial support from parents/carers, family, partners, and friends, being able to live within the parental home whilst studying, and for care experienced students, prioritisation for local authority housing and other support.

Receiving financial support with accommodation

Parents were a key source of financial support for accommodation. Examples of support for accommodation provided by parents included: making regular or more ad hoc payments towards students' rental costs; paying for a year's worth of rent in a one off payment to the university or landlord; assisting with rental deposits; buying a property for their child to live in while studying; and, more commonly, through allowing students to remain in the family home while studying and therefore reducing or avoiding costs associated with paying rent. Most students from the qualitative research who lived at home did not contribute financially towards household expenses, often referred to as 'digs', meaning it was far cheaper to live at home than move away and they were able to build up savings as a result. For students living at home who did contribute towards the financial running of the household, it was not common for families to have formal arrangements in place. Instead students said they occasionally gave their parents money for groceries or did grocery shopping as part of their contribution. Others had a more formal arrangement in place whereby they made regular financial contributions.

"It was cheaper to commute […] I paid my parents money to stay at home and then factoring in the cost of trains and stuff it still was cheaper than renting. (Full-time undergraduate student)"

Students' partners were also an important source of support with accommodation costs with some students describing how their partner subsidised their accommodation costs. This was often done through informal arrangements in distribution of rent or mortgage payments, and/or through flexibility in contributions to these payments, with partners taking on extra or sole responsibility for housing costs, often as a result of them working full-time. Students said that this enabled them to continue with their studies when they otherwise would not have been able to afford their accommodation while studying.

Accommodation support for care experienced students

Care experienced students highlighted the benefits of receiving assistance with their accommodation costs. As a result of care experienced individuals being given priority for social housing up to the age of 26, some lived in local authority housing with low rental costs. Others had their housing costs partially or entirely subsidised by their local authority, or were able to access accommodation-specific support from their universities via scholarships which covered accommodation costs for a year. Some care experienced students also mentioned their university offered 365 days of free accommodation for care experienced students. However, a care experienced student who had their rent paid by the local authority said they had 'no idea' this option was available until they re-engaged with their local authority social worker after a long break. It was then that they also found out they were eligible for a Leaving Care Grant which helped them furnish their home.

"My rent is around £500 a month. I am quite lucky. […] It's paid for at the moment by the local authority but I didn't actually know - when I signed up for the course, I had no idea that was available. It was by sheer luck that I happened to mention - it was the first time I'd spoken to anyone at the office in years and they said, 'We can pay your entire rent cost. It doesn't have to come out of any bursary money.' So I nearly missed out on that opportunity but luckily mentioned it. (Care experienced student focus group)"

Factors which make it harder to access accommodation

The high cost of accommodation

Students highlighted the high cost of rent – be that of university-owned accommodation, purposely built student accommodation or private rentals – as a key issue which impacted on their experiences of accommodation. Halls of residence, both university-owned and private, were viewed as being particularly expensive. University students noted that the combined income from loans and bursaries is insufficient to cover rent as well as other living costs, noting how rent has increased in recent years. There was a view among students that some towns and cities are cheaper to live in than others. Recent rent prices made some students reluctant to move, for fear that they might end up paying more.

"I think particularly with [name of city], I know the rent has gone up very crazy particularly to last year. It just can't – grants and those loans don't – will never really cover it. (Full-time undergraduate student)"

"So I am actually considering moving in with my partner next year but I've been looking at rentals just to sort of gauge what we might expect when we look for a place next year and they're a lot higher than they were 2 years ago when I found the place I'm living in now. Yeah, I believe [name of city] is sort of…rent prices have increased the fastest in the UK over the last year. So it is hard to find places, in fact a friend of mine she recently had to move into a flat and she's paying about £800 a month. Yeah, so it is expensive. (Full-time undergraduate student)"

In particular, accommodation in close proximity to universities and colleges in the bigger cities was viewed as being prohibitively expensive. To find cheaper properties, students described having to select rentals further away from their institution, which increased their commuting distances and costs. In some cases, students spoke of living in a different city to where they studied, in order to manage their housing costs. Students attempted to balance accommodation and commuting costs when finding accommodation. Some said they could not afford to move closer to their college or university, while others said that once they took into consideration commuting costs, staying closer to their institution was a better option.

"Back when I was doing my other course I was staying in student accommodation and then I stayed in rented accommodation and a big factor for that was if I stay close to the college it's slightly more expensive but I don't have to pay for transport so that's a big chunk of money that I can save there so…that was a pretty big factor for where I was staying. (FE student focus group)"

Lack of student accommodation in student areas

Another factor raised by students was the lack of suitable student accommodation in some areas, with students describing a high level of competition for rental properties. Some suggested the lack of student accommodation was impacted by the rise of short-term lets. Others mentioned the challenges associated with trying to find accommodation which has been deemed a House of Multiple Occupancy (HMO), with the view that HMO properties are expensive and often lower quality.

"In [city], it's an absolute catastrophe. It's not really enjoyable to be a student at university and then to not even live in that town. […] speaking to some of my friends who are in high school, it's an actual obstacle to their studies. They would say [city] sounds really nice, they would speak to me because they know I go there, and then they'd find out, by the way, it's average £800 for rent and they know they can't afford that. […] right now [city] is just filled with Airbnbs that take away actual homes that people can live in. (Full-time undergraduate student)"

Additional challenges in finding accommodation for students who are care experienced, estranged and carers

There were some groups of students who found it more difficult to access accommodation than others. Estranged and care experienced students described some of the difficulties they faced in securing accommodation as a result of not being able to live with or rely on financial contributions from their parents. A key aspect of this was not being able to use parents as a guarantor for rental agreements. Not having a guarantor made it harder to access properties to rent, with some commenting that private landlords were reluctant to rent a property without a guarantor. One student described having to pay much more than they had originally budgeted and having to live much further away from their institution than their peers due to not having a guarantor to help them secure affordable accommodation.

"I know for me, my place of living - when I had to leave my home, I think I had to keep upping my budget because nobody would take on a 19-year-old in their own house. I don't blame them but it was down to my responsibility to find somewhere and the longer it went on, the more places I got rejected with. It was going out further, raising the rent. Before you know it, I was an hour and a half away from where I used to live and the rent is something way higher than I should be on because I didn't have that guarantor. I didn't have someone that could help me. I think being care experienced has really affected where I've lived, where I'm living now, compared to all my friends. (Care experienced student focus group)"

"I also have to leave halls in June and I don't have a guarantor. I won't be a student at the university [as will have graduated] so I can't use the scheme that they've got where if you're estranged, they offer you guarantorship. So I'm a little bit screwed in that regard but we'll see. (Estranged student focus group)"

The accommodation options available to student carers were also limited. Caring responsibilities meant it could be difficult to find flexible work, which made it harder to afford rental costs. The need to be close to the people they cared for also meant that they tended to have to live close to, or with, the people they cared for.

Impact of commuting

Students' experiences varied in terms of the distances they were travelling to college or university. Some had very short commutes and were able to walk or cycle. Others were travelling longer distances by car, bus or train. Some students had commutes of up to two hours in each direction. While commuting from their own home or that of their partner's or parents allowed students to reduce their rental costs, it impacted on students in a variety of ways. The cost of travel was a key issue for some students. While those aged under 22 were able to benefit from free bus travel, others highlighted the cost of taking the bus or the train. Some students, particularly those who travelled longer distances, spoke of how tired they felt as a result. Long commutes could make it harder to fit in time for both academic study and paid work. Classes with a 9am start time were particularly problematic for commuter students, as a student with a travel time of 2.5 hours each way explained:

"I think it would be fine, but during the new semester, one of the [classes] starts at nine o'clock in the morning, so I have to get up at like, five, and then try and get there in time. I'm still late because obviously the traffic and stuff like that when I have to get the bus. That's not so great, but I know that it's not the lecturer's fault. He tried to get a later slot, but he couldn't. (Full-time postgraduate (Masters) estranged student)"

Experiences of homelessness

Some students who participated in the qualitative research had experienced homelessness, either previously or at the time of the interview or focus group. This included both college and university students and students who were care experienced, estranged and/or parents who had lived in homeless accommodation and those who were having to stay with friends due to not being able to find an affordable home. Those who had been homeless in the past spoke of the impact this had on their studies, with some having dropped out of school or college as a result. A student who was in temporary accommodation staying with a friend was considering dropping out so as to be able to earn more from paid work.

"If I wasn't staying with my friend, I don't think I could keep a house going with being a student as well because I'd have the whole whack to pay on my own. (Full-time FE student parent)"

Contact

Email: socialresearch@gov.scot

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback