Self-harm strategy development: qualitative evidence

Supporting development of a self-harm strategy for Scotland, what does the qualitative evidence tell us?

Methods

The methodology for this review was informed by Sattar et al.’s (2021) guidance on the principles of meta-ethnography, which outlines a seven-stage process for the synthesis of qualitative studies. This was identified as the most appropriate framework to use to conduct the meta-analysis, as it facilitates exploration of how the included studies relate to each other, while also allowing the reviewer to develop new insights derived from considering the full range of studies together. With a qualitative synthesis, the goal is interpretative rather than one of objective data aggregation (Rees et al., 2015). The principles of meta-ethnography explicitly acknowledge that the findings offer just one possible interpretation of reality, while also acknowledging the active role of both the reviewer and the initial study authors in the research process. Uniquely it allows for key themes and concepts to be explored and translated within and between studies.

Search strategy

From an early stage, we identified that defining self-harm could prove challenging when devising our literature search strategy. Our aim throughout this review was to reflect participants’ own experiences, understandings and definitions of self-harm, rather than to impose our own. Particular consideration was given to whether our search should include papers that explored experiences of suicide attempts or self-harm with (either possible or confirmed) suicidal intent. We took a pragmatic approach here. As large numbers of eligible papers were anticipated, we did not use search terms relating to suicide in our database searches. However, once searches were complete, we did not screen out papers where self-harm was understood or reported as suicidal. In this way, we kept our focus on the concept of self-harm (and not suicide), while also including narratives from participants whose understanding and experience of self-harm was in the context of suicidality. It is recognised that this approach may pose some limitations and may have precluded more in-depth exploration of suicidal self-harm. At data extraction stage, we included information on whether – and how – self-harm was defined in the study, including those exploring suicidal self-harm. This contextual information was considered as part of the overall synthesis.

Searches were conducted on ASSIA, IBSS, Ovid (PsycInfo, Medline and Embase) and PubMed. The initial search strategy was refined on PubMed (See Fig. 1) before being adapted to other databases where required.

Figure 1: PubMed search terms

((“self injurious behaviour”[MeSH Terms] OR “self harm*”[Title/Abstract] OR “self injur*”[Title/Abstract] OR “suicide attempt” [Title/Abstract] OR “non suicidal self injury” [Title/Abstract]) AND (“lived experience” [Title/Abstract] OR “lived experiences” [Title/Abstract] OR “qualitative” [Title/Abstract] OR “interview*”[Title/Abstract] OR “focus group” [Title/Abstract] OR “thematic analysis” [Title/Abstract] OR “phenomenol*”[Title/Abstract]) AND 2012/01/01:3000/12/12[Date – Publication] AND “english” [Language])) AND ((20212/1/1/1:3000/12/12[pdat]) AND (english[Filter]))

Study selection

Studies were screened to ensure they met the inclusion criteria (Table 1). Papers were included in the review if they were carried out in the UK and reported research published between the dates of 2012 and 2022, exploring the experiences of people who self-harm. As the aim of this study was to better understand lived experience, studies that only explored carer and professional experiences were not included. Studies that included both lived and carer/professional experiences were included only where accounts from these different groups were analysed and reported separately. Studies with participants of all ages were included. Importantly, our focus was on experiences and behaviours that participants, themselves, defined and understood as self-harm, regardless of intent. Where papers included accounts of behaviours or experiences that could be considered injurious to the self (e.g. extreme sports, drug use), these were excluded unless participants themselves considered them a form of self-harm. This could only be determined following careful reading of the studies, with particular attention paid to narratives from participants.

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria | |

|---|---|---|

| Location | UK | Countries outside the UK |

| Population | Studies with participants of any age who have lived experience of self-harm. | Studies which only include the experiences of carers, healthcare professionals or others who do not have lived experience of self-harm |

| Methodology | Qualitative studies Mixed methods studies with a qualitative element. | Quantitative studies |

| Concepts | Experiences of self-harm, of any kind and intent, as self-defined by study participants Experiences of suicide attempts | Studies reporting experiences and behaviours that participants did not consider to be self-harm (including those that could potentially be classed as injurious to the self, such as drug use, extreme sports, piercings, or body modification) |

| Date | Published between 2012 and 2022. | Published before 2012 or after 2022. |

| Language | English | Languages other than English |

| Literature | Peer reviewed articles PhD theses DClinPsy theses | Grey literature MSc or Bachelor level theses Blog posts or unpublished papers |

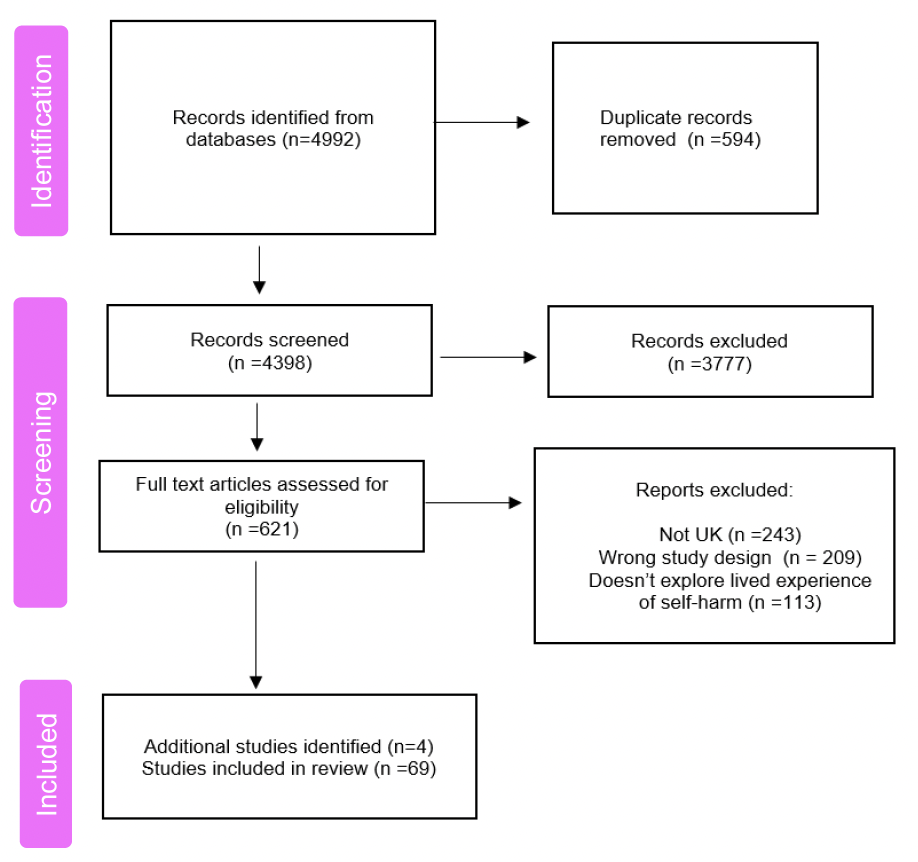

The study selection process is illustrated below following the PRISMA preferred reporting items guidelines. Searching began in July 2022 and concluded in September 2022, with electronic searches producing a total of 4992 hits across all databases. These were screened primarily by one reviewer, with input from a second reviewer where necessary. Following removal of duplicates and irrelevant studies, the number of potentially relevant studies was reduced to 621. These studies were read in full to determine whether they met the inclusion criteria and research questions. The majority of these studies were excluded due to being from outside the UK (n=243), having the wrong study design (n=209), or not addressing lived experiences of self-harm (n=113). The remaining 65 studies were included in the review, along with a further 4 identified through hand-searching of reference lists.

Data extraction and quality appraisal

A data extraction form was developed (See Appendix 1). Extracted data included: study aims; setting; participants; methods; summary of themes and findings and a summary of quality appraisal. Information was also included about whether – and how – self-harm was defined or conceptualised in each study.

As noted by authors of other meta-ethnographic reviews (Jones et al., 2014), whether to include quality appraisal in a meta-ethnographic review is disputed. Indeed, there is no absolute consensus on what constitutes high quality qualitative research (Ring et al., 2011). When deciding whether to perform quality assessment for this review, we considered the work of Toye et al. (2017, 2013), who highlight the issue of low inter-rater agreement for quality assessment, and note that appraisal tools generally focus on methodological, rather than the conceptual quality. Given these limitations of quality appraisal, we decided early on in the review process that studies would not be excluded due to poor quality. We have, however, performed quality appraisal using the CASP critical appraisal checklist for qualitative research. This was done primarily to enhance the rigour of the review, as well as to support in-depth reading of the studies. Overall, the quality of the studies was good, with some limitations as presented in our Findings section.

Analysis and synthesis

Qualitative meta-analysis was conducted following the seven stages of meta-ethnography (Sattar et al., 2021), as illustrated in Table 2.

Contact

Email: socialresearch@gov.scot

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback