Tackling child poverty - progress report 2023-2024: annex B - focus report on other marginalised groups at risk of poverty

A focus report looking at other marginalised groups at risk of poverty. It provides an evidence review on barriers across the three drivers of poverty and available evidence on what works.

Homeless families

Scotland has a strong legislative framework to protect families who are at risk of, or are experiencing homelessness. Anyone finding themselves homeless through no fault of their own is entitled to settled accommodation in a local authority or housing association tenancy or a private rental.[3]

However, being homeless can make it harder to escape poverty. It removes the home base from which parents can seek and maintain employment,[4], [5] and in some cases, may take children away from the location of their school meaning higher transport costs.[6],[7] It can remove local supportive social networks,[8],[9] and hinder healthy eating and exercise.[10] This section looks specifically at barriers homeless families face when living in poverty and provides some evidence of what works.

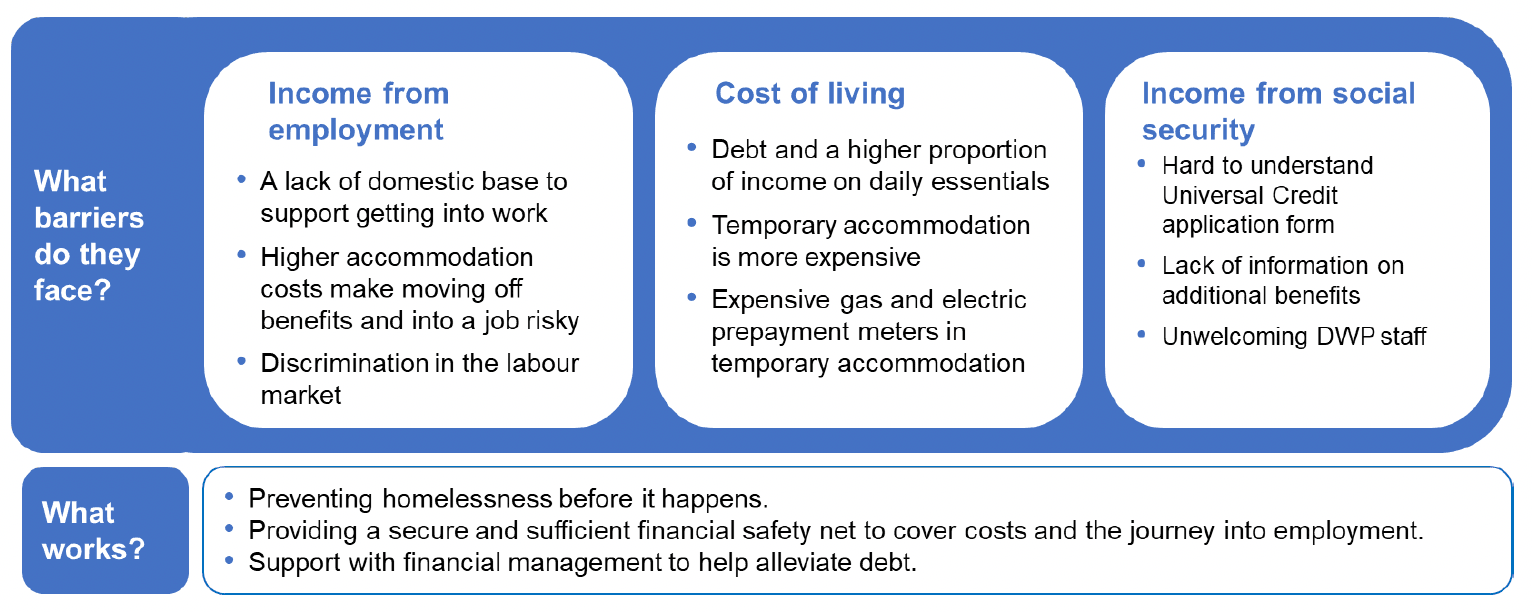

Graphic text below:

What barriers do they face?

Income from employment

- A lack of domestic base to support getting into work

- Higher accommodation costs make moving off benefits and into a job risky

- Discrimination in the labour market

Cost of living

- Debt and a higher proportion of income on daily essentials

- Temporary accommodation is more expensive

- Expensive gas and electric prepayment meters in temporary accommodation

Income from social security

- Hard to understand Universal Credit application form

- Lack of information on additional benefits

- Unwelcoming DWP staff

What works?

- Preventing homelessness before it happens.

- Providing a secure and sufficient financial safety net to cover costs and the journey into employment.

- Support with financial management to help alleviate debt.

Who are they?

Homelessness can be experienced by many different people. We see that there is overlap between the characteristics of those facing homelessness and the priority groups most at risk of poverty. For example:

- 11% of homeless households are from a minority ethnic background[11], compared to 4% in Scotland’s general population[12]

- 51% of homeless households have someone with at least one additional support need[11] compared to 34% of pupils in Scotland’s general population[13]

- 22% of homeless households are headed by a single parent, compared to 4% of Scottish households more generally[11]

In recent years, there has been a rise in the number of children in temporary accommodation (any accommodation used between the point of a homelessness application and the point at which the local authority arranges settled accommodation[14]), an increase which accelerated following the onset of the pandemic and has not slowed since.

What barriers and challenges do homeless families experience in relation to child poverty?

Poverty and homelessness are intrinsically linked.[7],[15] Research on UK families has shown that homelessness typically arises from both individual and structural factors. Structural factors include adverse labour markets driving low earnings, changes to welfare benefits,[16] rising private rental costs, and a lack of social housing,[17] while individual factors include mental and physical ill health, and relationship breakdowns. This is particularly relevant for women, as many become homeless due to relationship breakdowns, and frequently become the main carer for their children. Some circumstances are more complex, for example when the relationship breaks because of experiencing domestic abuse.[11],[16] Further detail is below in the section on victims/survivors of domestic abuse.

Challenges in increasing income though employment

For many families facing homelessness, the labour market can feel very far away. This is because many of their basic needs are not yet covered and their ability to find and maintain a well-paid, secure job can be limited.

Even when ready to access the labour market, the job seeker can perceive a barrier when they believe there is little to no difference between the value of benefits they receive and the level of wages that they would earn from working after living expenses have been taken into account.[18]

Homelessness can have a long-lasting impact on children, and on the parents (most often mothers)[11] who care for them. In some cases, families in temporary accommodation can face disruption to schooling, or additional costs and time in travelling to school.[19] Homeless children may struggle more to achieve academically and enjoy life, and are more likely to have behavioural problems[5] than peers in long term settled housing, all of which is anticipated to ultimately impact on the amount of income they will be able to make in later life through paid employment.

Challenges faced when aiming to reduce their costs of living

It is well documented that low income households spend a higher proportion of their income on essential costs of living.[20],[21] In Scotland 29% of renting households without children find it difficult to afford their current rent, rising to 37% of renting households with children.[22]

For financially struggling families at risk of homelessness through evictions from privately rented properties, finding a new home is the first challenge. Private rental properties can often be out of reach due to high and ever-increasing rents.[23],[4] Apart from high costs, judgement and avoidance of risk also plays a role. A UK-wide survey of those experiencing homelessness found that some landlords and letting agents are reluctant to let properties to welfare claimants and those on insecure work contracts.[4]

In Scotland, there has been positive progress made to increase the social rented housing sector. As of December 2023, 17,619 homes have been delivered, of which 13,483 (77%) are homes for social rent.[24] However, at the same time, there has been an increase in the number of children reported in temporary accommodation.[11] Temporary accommodation is generally at a higher rental cost than permanent accommodation, creating barriers to reducing costs when moving off the receipt of housing benefit into paid employment would not cover these higher rental costs.[18]

Other costs of living can also be quite significant. The cost of living crisis has had disproportionately harsh impacts on people facing homelessness. While living in temporary accommodation, people paying for gas and electricity must often use expensive pre-payment meters.[6] Low incomes coupled with the current high cost of food have also driven some homeless families to use food banks; in 2023, one in four people referred to food banks in the Trussell Trust network in Scotland were either homeless at the point of referral or had experienced homelessness in the previous 12 months.[25]

Challenges in increasing income through social security

Research with homeless individuals in Scotland on their experiences of access to welfare benefits has revealed several difficulties.[26] These include:

- Complicated, hard to understand Universal Credit application forms that required the privilege of a computer or phone with internet access

- A lack of available information on what additional benefits they were eligible for, or new benefit types that they now qualified for

- Unhelpful and unwelcoming interactions by DWP staff who were not sensitive to the mental health vulnerabilities of homeless people

Participants suggested more joined up services to better signpost them to benefits they were eligible for, training for DWP staff on a more sensitive approach, plus community hubs to provide support with accessing and navigating the benefits system. This is particularly relevant for those dealing with additional layers of disadvantage, if for example, they are homeless due to a relationship breakdown or are a victim/survivor of domestic abuse.

What do we know works to support homeless families?

Preventing homelessness before it happens. The best way to end homelessness for families is to prevent it from happening in the first place. The Homelessness Strategy outlines a plan of action with a focus on preventative policies. This includes measures to protect tenants’ rights and avoid evictions to prevent homelessness, and deploying a cash-first approach to support families struggling with their housing costs.

Understanding that barriers and needs are different depending on families’ circumstances. Homelessness will be experienced in different ways depending on the reasons for being homeless or the family’s characteristics. For example, women starting a facing homelessness following a relationship breakdown, will have specific barriers to face. Particularly because in many cases they will be the main and sometimes sole carer for their children, in other cases they will have been the victim of abuse by their partner. When other layers of disadvantage are added, such as a disability, then the support required is more complex.

A secure home as a first priority, but that is only the beginning. There is ample evidence on the effectiveness of long term rent subsidies and other housing support to provide housing stability and prevent long term homelessness.[27],[28] But support in having a secure home is only the beginning of the journey out of poverty. Evidence on resettlement experiences of homeless people in the UK has indicated that levels of worklessness and poverty continue to be high after (formerly) homeless households accessed settled housing, with three in five of study participants struggling to manage financially after 6 months.[18] This suggests that housing policies should work alongside social security support and long term employability support to ensure sustainable sources of income into the household.

Financial management can be difficult without a safety net. Long term low incomes from employment can force families into debt as they attempt to meet general household or one-off costs.[18] Recent evidence shows that neither the resettlement of a family into stable accommodation nor support into paid employment will in and of themselves (or in combination) be enough to lift the vast majority of homeless people out of poverty.[18] Instead, a clear understanding of a family’s need and a combination of various forms of support across all three drivers of poverty is required.

Contact

Email: TCPU@gov.scot

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback