Tackling child poverty - progress report 2023-2024: annex B - focus report on other marginalised groups at risk of poverty

A focus report looking at other marginalised groups at risk of poverty. It provides an evidence review on barriers across the three drivers of poverty and available evidence on what works.

Families of people in prison

Families of people serving a custodial sentence have been referred to as the ‘hidden’, ‘innocent’, or ‘collateral’ ‘victims of punishment or crime’.[78], [79] When a person is in prison, there can be financial, social, and emotional impacts on family dynamics and relationships of those outside.[79]

Graphic text below:

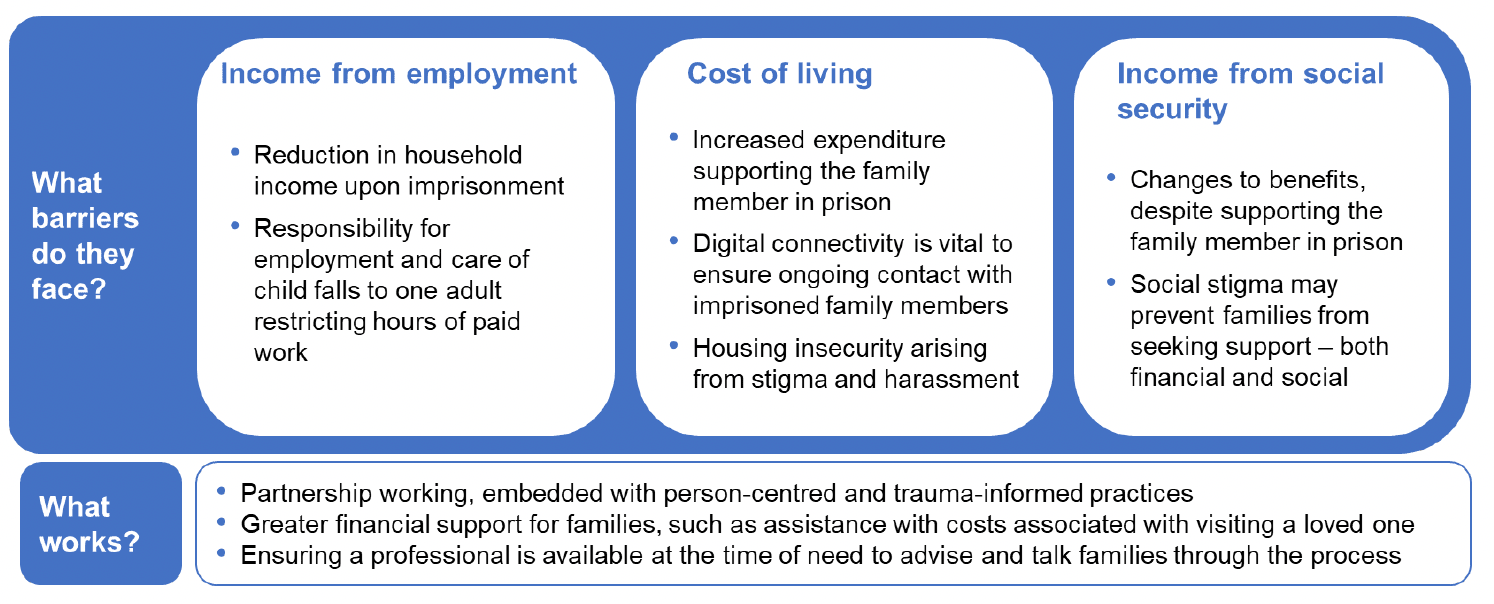

What barriers do they face?

Income from employment

- Reduction in household income upon imprisonment

- Responsibility for employment and care of child falls to one adult restricting hours of paid work

Cost of living

- Increased expenditure supporting the family member in prison

- Digital connectivity is vital to ensure ongoing contact with imprisoned family members

- Housing insecurity arising from stigma and harassment

Inform from social security and benefits in-kind

- Changes to benefits, despite supporting the family member in prison

- Social stigma may prevent families from seeking support – both financial and social

What works?

- Partnership working, embedded with person-centred and trauma-informed practices

- Greater financial support for families, such as assistance with costs associated with visiting a loved one

- Ensuring a professional is available at the time of need to advise and talk families through the process

Who are they?

In 2022/23, the average daily prison population was 7,426, [80] with the average length of custodial sentence being 329 days.[81] More specifically, 49% of individuals arriving to prison in 2022/23 came from the 20% most deprived areas of Scotland.[80] Those in prison are also more likely to be men. In 2022/23, women made up 6% of the individuals experiencing imprisonment.[80]

It is not possible to assess exactly how many children are affected by the imprisonment of a family member. Results from the 2019 Prisoner Survey suggest that, of all those in custody, three in five (61%) reported having children, with over one third of this group (37%) receiving visits from their children while in prison.[82] A widely quoted estimate from 2012 suggests that between 20,000-27,000 children are affected by parental imprisonment in Scotland.[78] This figure includes those with a parent in prison, but not those who are impacted by wider family members’ imprisonment – including that of siblings. The figure was last estimated in 2012 and is likely to have changed since as there has been a significant transformation in the number, and profile, of people in prison over the past decade.[83]

The imprisonment of a household or family member can be a highly stressful event for a child or young person. Indeed, having a parent or carer in prison and has been identified as an Adverse Childhood Experience. This means that children and young people affected are more likely to have adverse and lifelong impacts on health and behaviours.[84],[85],[86],[87]

What barriers and challenges do families of people in prison face in relation to child poverty?

Imprisonment can play a role in creating, sustaining, and deepening poverty for those families with a loved one serving a custodial sentence.[88],[89],[90] Societal stigma can limit the support given to families with a loved one in prison. Other types of loss, such as a family member in the armed forces or a death are deemed more acceptable methods of a change in family structures and dynamics, while imprisonment does not tend to receive the same levels of social support and acknowledgement.[89]

Challenges faced when aiming to increase income through employment

Reduction in household income from paid employment. A reduction in household income from paid employment can occur if the person in prison was previously in paid work. One research study on the cost to families of imprisonment estimates that an average of £890 a month is lost from the household income when a partner is imprisoned, with the family financial situations moving from stable to unstable.[88]

One adult, multiple roles. Following imprisonment, the adult caregiver remaining at home, often a woman, must take on multiple roles and responsibilities, including those the person in prison used to do.[79],[88],[89],[91] Mostly, this includes employment. But beyond having to manage increased hours for paid work or start it in the first place, the parent often becomes a sole carer for their child(ren) while navigating and caring for their partner in prison (e.g. buying clothing, telephone calls, visiting).[88] This pressure on time[92] can restrict the hours the carer can do paid work and can exacerbate existing disadvantages.

Mental health and wellbeing. The evidence repeatedly highlights the emotional distress partners face supporting someone in prison due to limited financial support, emotional support, and the stress associated with supporting a loved one in prison.[88] These stressors can lead to family members being forced to give up work.[93]

Challenges faced when aiming to increase income through social security

Changes to benefit entitlement. Families previously making a joint claim for social security are required to make a single claim upon imprisonment of the other claimant. This can lead to changes in Universal Credit and other support they may receive, which reduces the household income, despite still supporting the family member in prison (see the following sub-section on costs of living).[93] For new claimants, the process of applying for benefits can be stressful and draining while the delay in receiving Universal Credit can be problematic for families.[88]

Social stigma. The stigma associated with imprisonment can lead to family members attempting to conceal and mask the incarceration of a family member. This prevents them from seeking support, both social and financial.[94]

Challenges faced when aiming to reduce their cost of living

Supporting the imprisoned family member. Family income tends to decrease following imprisonment of a family member, but expenditure can increase.[79] Evidence suggests that the median total spent per month supporting a family member in prison is £180.[88] These costs entail: visitation – including travel costs and food[95]; payment into the prisoner’s Personal Account; clothing; or stamps to send letters.[88]

Digital connectivity. Keeping in touch with imprisoned family members is vital, especially for children and young people to maintain parental-child relations.[92] However, there can be issues to ensure ongoing contact. Research highlights how during times of financial strain, internet is often cancelled to reduce costs, while other households struggle to set up video calls due to not having appropriate technology or not having the correct identification (which comes associated with a cost, e.g. passport or driving licence).[88]

Cutting costs. Living on pressured household budgets can lead to the primary caregiver skipping meals and not buying clothes in order to provide for their children and imprisoned partner. This can extend to limiting or stopping socialising and attending activities which cost money,[88] despite social support being a protective factor to mediate the harmful effects of the imprisonment of a family member.[89]

Housing insecurity. When a family member goes into prison, benefit entitlement changes. This can impact on their home situation. Research suggests that some families need to move home due to changes to their benefit entitlement,[96] for reasons of stigma or harassment,[88] or due to loss of household income and change in financial circumstances, which may leave families unable to afford to remain in the familial home.[97]

What do we know works to support families of people in prison?

Across the evidence base, there are clear learnings on what may work to best support families of people in prison, particularly around partnership working. The Vision for Justice recognises the need for collaborative working embedded in person-centred and trauma-informed practices which take into account the system-wide impact of justice actions. How this looks in practice varies throughout the evidence, but there is an understanding that families may place greater trust in third sector services rather than state services (due to their engagement with the justice system),[98] and there is a role for services to align and work closely together in order to ensure appropriate, timely, and valuable support for families with a loved one in prison.

Other areas for support, include:

- Greater financial support for families with a family member in prison, e.g. greater assistance with costs associated with visiting a loved one in prison.[88],[93]

- Further opportunities for family bonding and provision for children of prisoners including family days, seasonal events, and special sessions (e.g. Book Bug).[99]

- Accessible information at the time of need, for example, greater awareness raising of the Scottish Welfare Fund.[88]

- Close contact with a professional, such as a Family Contact Officer, who is available at the time of need, and can advise and talk families through the process of imprisonment is viewed as crucial and instrumental.[99]

- For children and young people, ensuring a trusted adult is in place to provide a supportive relationship and consistent understanding and empathy.[100] For example, teachers may be well-placed to fulfil this role due to their regular contact with children and young people.[101]

Contact

Email: TCPU@gov.scot

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback