Just Transition: draft plan for transport in Scotland

This draft plan identifies the key challenges and opportunities that the transport sector faces in making a just transition to net zero. We are seeking views as part of a public consultation, which will run until 19th May 2025.

Annex C: People and Equity

The current transport system is unequal. Evidence demonstrates that emissions from transport are not fairly shared across income groups. Those on the highest incomes are responsible for a greater share of transport emissions, are likely to travel further, own multiple vehicles, as well as choose vehicles that have a higher concentration of negative effects in terms of emissions, pollution, and road safety. We also know that these negative impacts are not felt equally. This Annex provides further details on these various impacts.

Decarbonising our transport system poses potential risks in exacerbating existing inequalities. Examples of this include inequalities between those who do and do not own EVs (EVs cost £750 a year less to run than petrol cars[49]), those with off-street charging vs those without seeing £500-£1000 higher recharging costs. Such inequalities are expected to reduce as upfront costs of EVs continue to fall. There is an additional disparity between those who have access to reliable and affordable public transport where they live and those who do not. This is why delivering a just transition will require policy solutions that ensure the costs and benefits of decarbonisation are distributed fairly.

Income and Emissions

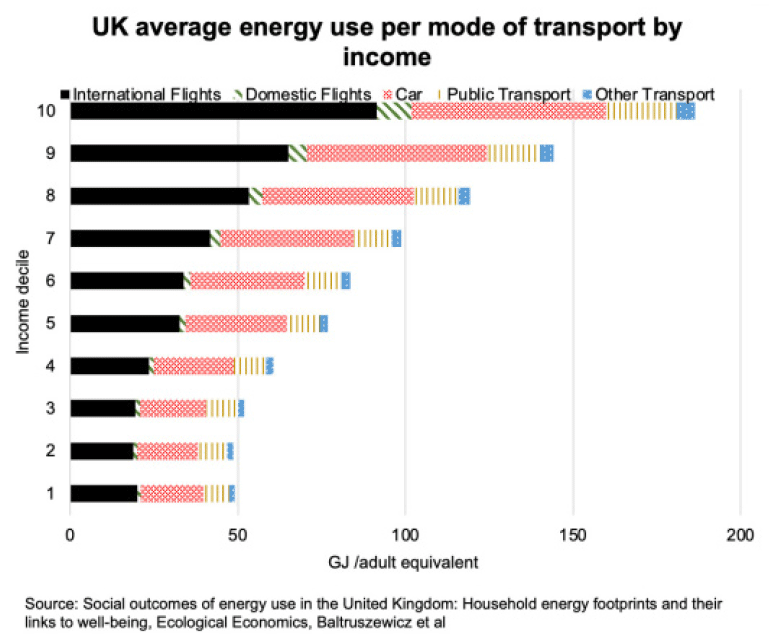

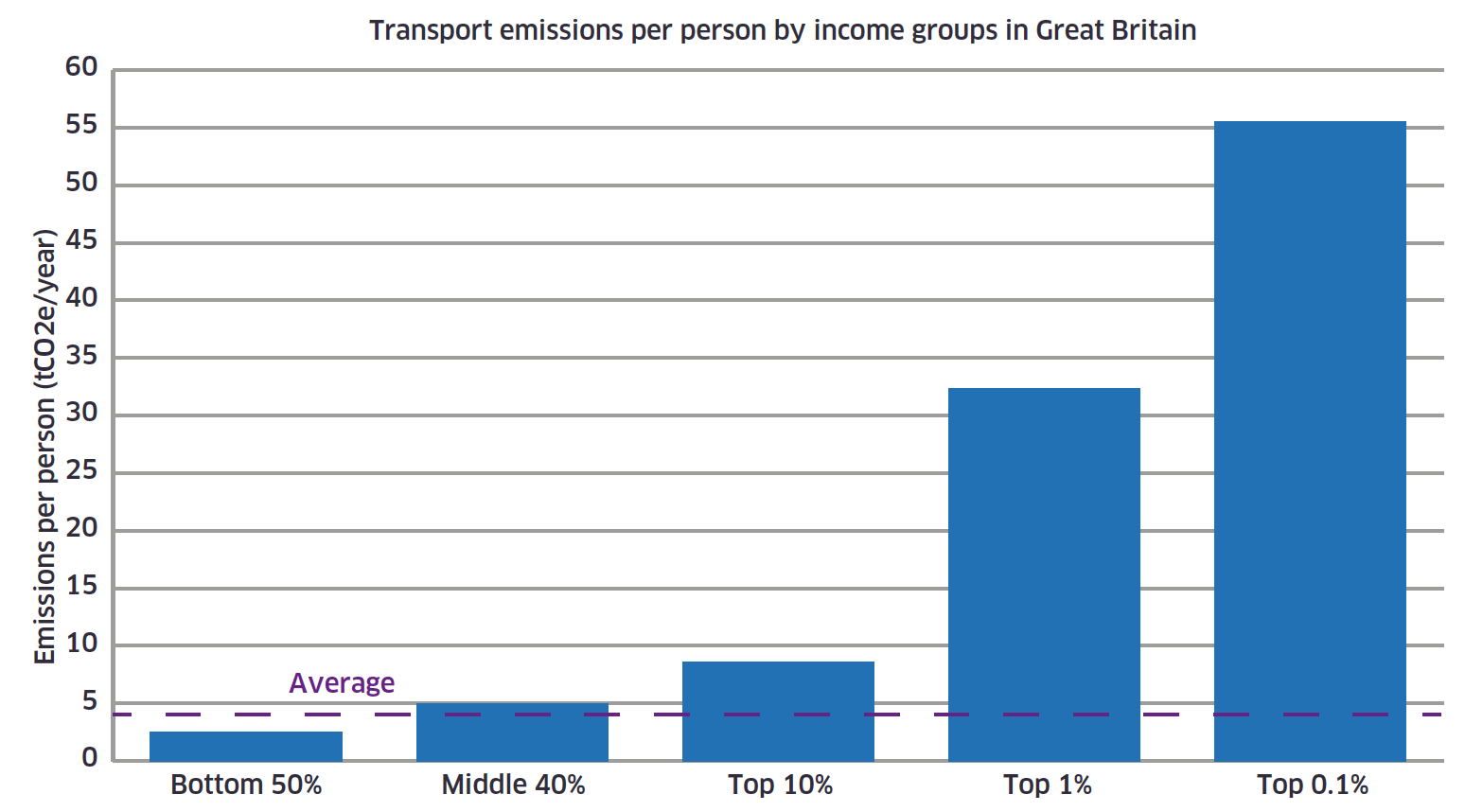

Those on the highest income emit the most transport emissions

(Figure source: IPPR – Moving together[50])

The following outlines some disparities in emissions and travel behaviours across income groups:

- The carbon footprint of the richest 5% of households in Scotland between 2017-2019 with reference to aviation was 11 times higher than the poorest 5% of households. For public transport (which includes rail and buses), it was 5 times higher.[51]

- Those on higher incomes are responsible for a higher share of emissions and a disproportionate number of journeys (particularly air travel and long car journeys). The IPPR-Moving Together report presented the following figures for Great Britain:

- The highest emitting 10% of the population are responsible for 42% of all transport emissions, and;

- The highest earning 0.1% of people in Great Britain emit at least 12 times more from transport than average and 22 than more from transport than the lowest earners.[52]

- Those on higher incomes are more likely to buy new EV vehicles.[53] We also know that 14% of cars registered in 2022 weigh more than 2 tonnes, up from 3% in 2015 – the weight of EVs has a corresponding impact on the wear and tear of roads and emissions levels.[54]

- Scottish Household Survey data indicates that the highest earners in Scotland are more likely to own more than one vehicle, and those on the lowest incomes are much less likely to have access to a car.[55]

- Additionally, Scottish Household Survey data over the period 2015-2019 indicated people from households in the top 1% of incomes tend to drive further (median 8.3km travelled per car journey per individual) than those from households in the lowest 50% of incomes (median 5.3km). Therefore, those on the highest incomes in Scotland contribute more car use than those who earn the least, on an individual basis. As a group, people from households in the top 1% of incomes accounted for only 2% of the total distance driven. People from the lowest 50% of household incomes accounted for 30%.

Recognising that those on higher incomes are responsible for a larger share of transport emissions underpins the need for a greater burden of responsibility for action from this group to reduce both their car use and air travel from a just transition perspective. Nonetheless from a car emission reduction perspective, this group is too small in number to make the overall difference needed to reduce our car emissions .

Deliberative Research led by Ipsos

To inform the design and delivery of our just transition plans Scottish Government (through ClimateXChange) commissioned Ipsos Mori to carry out deliberative public engagement on the fair distribution of costs and benefits in Scotland’s transition to net zero emissions. Deliberative engagement allows those involved to spend time considering and discussing an issue at length before coming to a considered view.

The research explored participants’ views on overarching principles of fairness, as well as the practicalities of implementing specific policies, such as Road User Charging, in a fair way. It also generated learning into the factors influencing changes in participants’ attitudes, beliefs or values as a result of engaging in the deliberative process.

Key messages for the transport sector

- The vision for a future net zero transport system was considered difficult to achieve without significant investment in transport infrastructure across Scotland.

- For any form of Road User Charging to be considered fair, participants concluded that different circumstances and needs should be taken into account (e.g. those on low incomes, with health conditions or disabilities, the elderly or those living in rural communities) rather than taking a blanket approach.

- It was felt that widespread application of Road User Charging would be unfair in rural areas unless there was improved access to public transport.

- Participants also highlighted the importance of allowing sufficient time for people to prepare for any changes being introduced.

Transport Poverty

Public Health Scotland define transport poverty as: the lack of transport options that are available, reliable, affordable, accessible or safe that allow people to meet their daily needs and achieve a reasonable quality of life.[56] We know that the proportion of income spent on transport is higher for those on lower incomes and that travel costs are a consideration for many, with 54% of respondents to the Scottish Household Survey in 2023 reporting that transport costs affected the method of travel they used.[57] Furthermore, transport poverty disproportionately impacts groups who face existing structural disadvantages, including disabled people, women and specific ethnic groups.

This disparity also extends to vehicle access and ownership. Only 50% of people in the lowest income groups in Scotland have access to a car or van compared with 80% of the general population[58]. According to results from the Scottish Household Survey conducted in 2023, 28% of households have access to two or more cars and we know that it is higher income groups that are more likely to be in this category.[59] Despite having lower levels of car ownership, the negative impacts of car use fall disproportionately on those who are already more vulnerable and disadvantaged, including air quality and noise pollution.[60] For example, socially vulnerable neighbourhoods in large urban areas in Scotland are 50% more likely to be exposed to poor air quality.[61]

Furthermore, higher income groups are also more likely to benefit from affordable bikes through Cycle to Work schemes or because they can afford them therefore benefiting from the increased investment in active travel infrastructure.

Peak Fares Removal Pilot

The Scottish Government subsidised the temporary removal of ScotRail peak fares from 2 October 2023, with the aim to encourage people to switch from car and travel by train by making public transport more accessible and affordable over the pilot period. The pilot has since been extended twice, to run for twelve months in total and ended on 27 September 2024.

Analysis of the pilot that while there has been a limited increase in the number of passengers during the pilot, it did not achieve its aims of encouraging a significant modal shift from car to rail.[62] The pilot also primarily benefitted existing train passengers and those with medium to higher incomes and although passenger levels increased to a maximum of around 6.8%, it would require a 10% increase in passenger numbers for the policy to be self-financing.

Characteristics of Use

The different patterns of transport usage outlined above require consideration when developing solutions. The Public Health Scotland report on Transport poverty noted the following key characteristics for particular groups:

- Typically, disabled people make fewer and shorter trips,

- Higher-skilled, high-income jobs are increasingly located in cities along good transport corridors or city centres, while low-skilled jobs are increasingly located on the periphery,

- Women are more likely to trip chain (make a series of trips for different purposes within a time period) which is more costly and time intensive, and

- Public transport is not always aligned to shift work.

Engagement Quote Box: “Who doesn’t want to play their part in climate change and reduce their own costs – but electric cars are out of the budget of low-income households”. - Poverty Alliance, Low-income Householder session

There are social, economic and health implications of restricted transport options which include (but are not limited to) employment and training opportunities, access to education and medical services, as well as social isolation. This highlights the need for integrated solutions and planning and our Transport to Health Delivery Plan, which is taking forwards commitments focussing on access to healthcare in a fair and equitable way, provides a particular example of work done in this area. Recognising the interrelationship between transport and wider social, economic and health outcomes will be critical to securing a just transition in the sector.

Contact

Email: TJTP@gov.scot

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback