Understanding the Cost of Living Crisis in Scotland

This report draws together analysis from a wide range of sources to provide a summary overview of evidence on the cost of living crisis and its impact on Scotland. It includes evidence from Scotland and the UK as well as from other European countries.

2. The cost of living crisis in Scotland

The cost of living crisis in Scotland was caused by a rapid and sustained increase in inflation in 2021 and 2022 which meant that the price of goods increased at a faster pace than household incomes.

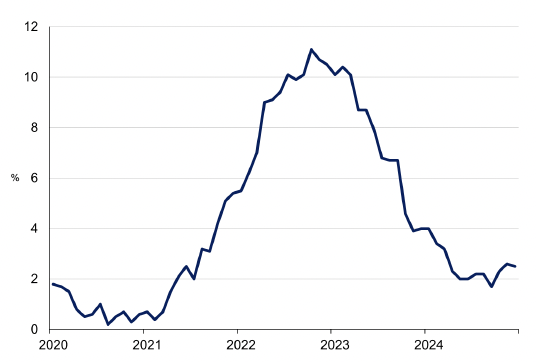

The UK inflation rate, as measured by the Consumer Prices Index (CPI) (which measures the average change from month to month in the prices of goods and services purchased by most households in the UK), rose from under 0.5% in February 2021 to a peak of 11.1% in October 2022. At its peak, the rate of inflation within the UK reached its highest rate for 41 years.

From October 2022 CPI gradually reduced to reach the Bank of England’s target rate of 2% by June 2024. Figure 1 below shows the sharp spike in inflation that occurred in 2022 resulting in an inflationary shock.

Source: ONS[2]

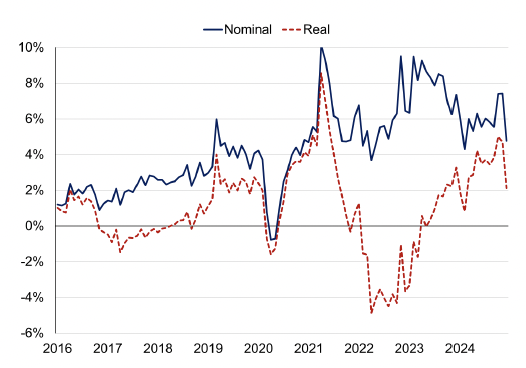

From early 2022 to mid-2023 the rate of inflation outpaced median wage growth in Scotland. Inflation also rose at a faster rate than benefits were uprated meaning that household costs were increasing at a faster rate than average household incomes. Figure 2, below shows the real and nominal earnings and annual growth from 2016 to November 2024.

Source: ONS PAYE RTI and CPI[3]

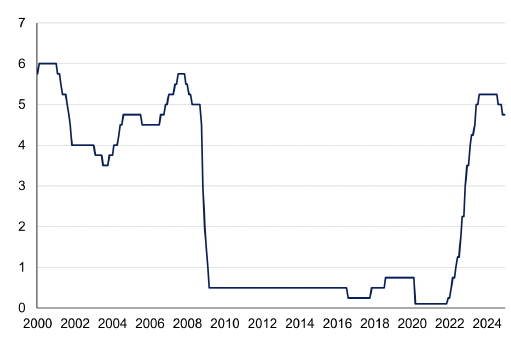

High inflation led the Bank of England to raise interest rates. From the end of 2021 the Bank raised interest rates 14 consecutive times from 0.1% in December 2021 to 5.25% in August 2023. As inflation has gradually stabilised, the Bank of England reduced interest rates twice in 2024 (in August and November) from 5.25% to 4.75%. The gradual pace of interest rate reductions reflects the persistence of some underlying inflationary pressures, most notably above inflation pay rises in some sectors of the economy.

Source: Bank of England[4]

2.1 Phases of the cost of living crisis

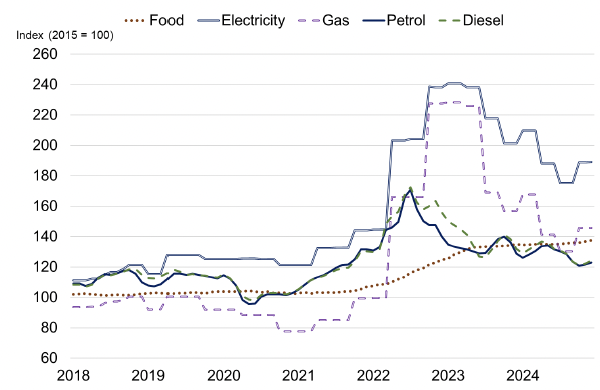

Whilst the headline CPI figure presents the overall rate of inflation it doesn’t show variations in the different component parts that make up the measure. Figure 4, below, shows the changes in price levels for electricity, gas, petrol, diesel and food since 2018. It illustrates the initial sharp increase in energy prices followed by the increase in food prices. While electricity and gas prices fell over 2023 and 2024 and the pace of food price inflation stabilised, price levels remain notably higher than in 2021 prior to the inflation shock.

Source: Scottish Government, ONS[5]

The rapidly changing economic picture set out in Figure 3 and Figure 4 resulted in the cost of living crisis progressing through a number of distinct phases over the last three years. These phases overlapped with each other to an extent, but received different public and political prominence as certain issues became more acute.

2.1.1 Phase 1: A focus on energy prices

During the initial phase in 2022, households and businesses were subject to very steep energy cost increases due to rises in energy wholesale prices and, as a result, changes in the Energy Price Cap. This was partially mitigated by the Energy Price Guarantee, where the UK Government funded the difference between the maximum price for consumers, and the Energy Price Cap. The changes to household energy bills resulted in a large increase in the percentage of households in Scotland in fuel poverty and extreme fuel poverty[6], significantly increasing costs for businesses and increasing fuel costs for motorists (with petrol and diesel pump prices peaking in July 2022[7]).

As household incomes came under increased pressure there was a corresponding increase in industrial action as employees demanded higher pay rises. Overall, the number of working days lost because of labour disputes in 2022 (2.5 million) was the highest since 1989[8]. Over the course of the crisis the proportion of people in Scotland who reported taking steps to reduce energy use in the home decreased from a peak of 65% in December 2022, to 45% in December 2024[9].

2.1.2 Phase 2: A focus on food price inflation

By early to mid-2023 food inflation became more of a focus as UK Government interventions were introduced in response to energy prices and the rate of energy price increases began to subside. This led the Resolution Foundation to argue in May 2023, that ‘the food price shock is about to overtake the energy price shock as the biggest threat to family finances’[10].

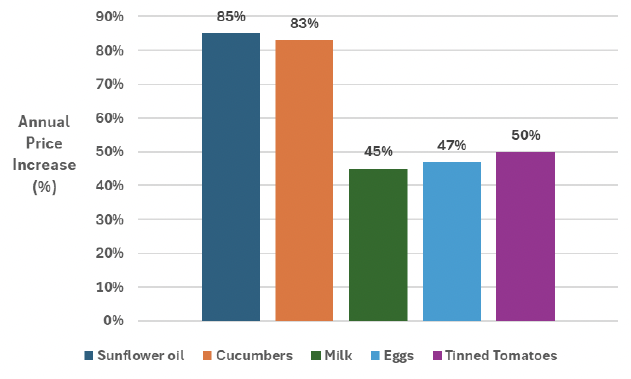

Annual food price inflation reached 19.2% in March 2023, the highest rate of increase in food prices since 1977[11]. The number of Scots reporting cutting back on essentials such as food peaked at 24% in February 2023 before falling to 15% by December 2024. In December 2022, 62% of households who said that they were managing less well financially[12] reported cutting back on essentials such as food[13]. Some food categories rose in price faster than others. Some of the foods subject to the biggest annual increases, such as sunflower oil (up 85%), cucumbers (up 83%) and dairy products are set out in figure 5 below.

Source: Food foundation[14]

2.1.3 Phase 3: A focus on rising interest rates

As the crisis progressed into late 2023 the focus began to incorporate increasing concerns about the impact of rising interest rates on mortgages and rents. When mortgage rates first began to rise, the impact was initially focussed on those purchasing a house and the relatively small share of households with a variable rate mortgage. Over time the impact became more significant as interest rates continued to rise and an increasing share of fixed rate mortgages reached their end of term[15]. By the third quarter of 2024, the number of regulated UK mortgages entering arrears had increased by 36% (compared to quarter one of 2022), although the number of mortgages going into arrears remains lower than the spike at the outset of the pandemic and notably lower than the peak recorded in 2008 during the global financial crisis.[16]

Furthermore, rents began to rise for people agreeing new tenancies in the private rented sector as landlords reacted to higher buy-to-let mortgage rates and other cost pressures (existing tenants were protected by emergency measures under the Cost of Living (Tenant Protection) (Scotland) Act 2022). There were also wider economic impacts of high borrowing costs for businesses.

Whereas low income households experienced higher inflation relative to high income households in the earlier, acute phase of the cost of living crisis, by mid-2023 high income households were experiencing higher rates of inflation as a consequence of rising interest rates (since high income households are more likely to be home owners).[17]

2.2 The causes of the cost of living crisis

The high rate of inflation within the UK seen in 2021 and 2022 was due to a number of factors including:

- Strong global demand for consumer goods – as the economy adjusted and recovered following the Covid-19 pandemic and associated lockdowns;

- Related supply chain disruption; and

- Soaring energy and fuel prices – particularly, but not exclusively, due to Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022[18].

The cost of living crisis was a global crisis with the US and Euro Area experiencing similar patterns of inflation. Inflation in the US and Euro Area peaked at 9% and 10.6% respectively. Some commentators have also argued that the UK entered the cost of living crisis in a weaker position than comparator countries due to the reduction in productivity and competitiveness that occurred as a result of Brexit[19].

Contact

Email: Tom.Lamplugh@gov.scot

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback