Understanding the Cost of Living Crisis in Scotland

This report draws together analysis from a wide range of sources to provide a summary overview of evidence on the cost of living crisis and its impact on Scotland. It includes evidence from Scotland and the UK as well as from other European countries.

3. The differential effects of the cost of living crisis on households

Whilst the cost of living crisis affected everyone, some households, services and sectors of the economy have been much more exposed to the effect of rising prices.

During the peak of the crisis low income households were subject to much higher rates of inflation due to spending a higher proportion of their overall income on food, transport and energy costs[20]. Some low income household types (such as households with disabled people) also incurred additional costs and / or received real-terms reduced income because of their particular characteristics and / or circumstances. Low income households were also more likely to be financially vulnerable, and entering the cost of living crisis in a position of financial hardship.

People on low incomes often end up paying more for essential goods and services. This is sometimes referred to as the ‘poverty premium’. Examples of this include the increased likelihood that low income households will be reliant on more expensive pre-payment meters, will be unable to move to the best fuel tariffs, and will be unable to access consumer credit.[21] There is also evidence that the prices of cheaper brands of food, drink and other grocery products increased much faster than more expensive varieties[22] meaning that poorer households were harder hit by rising costs.

By way of contrast some households, such as home owners with no or only a small mortgage and with sizeable savings, will have seen a net benefit from higher interest rates. For example the Resolution Foundation estimated that overall, the tenth of households with the most savings wealth will receive an average of £20,000 each, before tax from interest on savings[23].

The section below sets out summary evidence on how the cost of living crisis has disproportionately affected some groups. In reality there is a significant level of overlap between these groups and it is important to, consider the data from an intersectional perspective recognising that people are shaped by their simultaneous membership of multiple groups which can compound disadvantage. The section below is not comprehensive, but is included to illustrate some of the ways different groups have been affected.

3.1 Women

The First Minister’s National Advisory Council on Women and Girls published a report in May 2024 which summarised the multiple ways in which women have been disproportionately affected by the cost of living crisis[24]. The report presented evidence showing women are more likely to be in debt than men, more reliant on benefits, have lower savings and less access to occupational pensions. The report also highlighted evidence from third sector research that the crisis is exacerbating existing financial barriers that prevent women leaving abusive relationships and that instances of financial abuse are increasing as a result of the crisis.

Evidence from the latest YouGov survey for the Scottish Government[25] from December 2024[26], shows how the cost of living crisis has seriously affected women’s mental and physical health. When asked about the wider impacts of the cost of living situation in Scotland today 34% of women reported that their physical health has been negatively affected (compared to 27% of men) and 48% of women reported that their mental health has been negatively affected (compared to 39% of men). Furthermore the survey shows that the majority of women in Scotland do not feel that the cost of living crisis is abating. Seventy one per cent of women disagreed with the statement that it feels like the cost of living crisis is easing, compared to 62% of men.

3.2 Disabled people

The main piece of research on the effects of the cost of living crisis on disabled people in Scotland was a report published by the Glasgow Centre for Population Health and the Glasgow Disability Alliance[27]. It stated that since 2021, the cost of living crisis has created severe impacts for the most vulnerable members of society, creating an unfolding ‘social catastrophe’. The crisis has worsened poverty and financial insecurity, with disabled people unable to heat their homes, going hungry or eating a nutritionally deficient diet. The study presented multiple examples of where this had directly compromised the management of participants’ health conditions:

“I’ve to take my medication with a meal, three times a day. There has been days when I can only afford one half-decent meal. So when I’m taking my pills without a meal I feel pretty bad, my stomach isn’t right and I’m worried about the long term impacts that’s having on me” Focus group participant.

Households with one or more disabled person are more likely to be in poverty[28]. Disabled households are also likely to incur greater costs as a result of their disability. UK research from July 2024 showed that households with an adult limited a lot by disability are more likely to experience food insecurity (32%) than households with an adult not limited by disability (10%)[29]. People with chronic health problems or disabilities are more likely to experience destitution[30]. More than two thirds of people referred to food banks in the Trussell network, are disabled[31] and research by Trussell in 2023 found that many disabled families in Scotland are going without dental treatment (32%) and medication (8%) due to lack of income.[32]

3.3 Ethnic minorities

Minority ethnic groups are significantly more likely to live in larger households[33], to be unpaid carers and to live in private rented accommodation. These households are also more likely to have deeper levels of poverty[34] and so a greater proportion of their income is likely to be spent on essentials such as energy and food which have been subject to very high levels of inflation.

Over half of children in minority ethnic families (53%) are in poverty[35]. Non-white ethnic groups are at higher risk of food insecurity (32% for Black/African/Caribbean and 29% for Mixed/multiple) than white ethnic groups (13%)[36]. Black, Black British, Caribbean or African-led households and Migrants are disproportionately likely to affected by destitution[37]. Research by the National Centre for Social Research in 2023 found that nearly 40% of Black people were ‘were in arrears with household bills’ and this had increased from 19% in 2019[38].

3.4 Rural households

Rural and remote places in Scotland are more exposed to high inflation due to high levels of fuel poverty combined with other local factors such as higher food and transport prices. Significant parts of Scotland’s remote communities are particularly vulnerable to fuel poverty because the Scottish gas grid does not reach them, leaving them dependent on alternative sources of heating.

The 2023 Scottish Islands Survey[39] gathered views about different aspects of island life from Scottish island residents, including the cost of living and fuel poverty. It found that more than one fifth of respondents were concerned about paying for a range of everyday items in the next two to three months, such as household repairs and groceries, while one in ten were concerned about credit card repayments and paying the mortgage/rent. Paying for heating and hot water was found to be a particular concern. Almost half of islanders (45%) said that their home sometimes feels uncomfortably cold in the winter, an increase from 35% in 2020[40].

3.5 Larger households

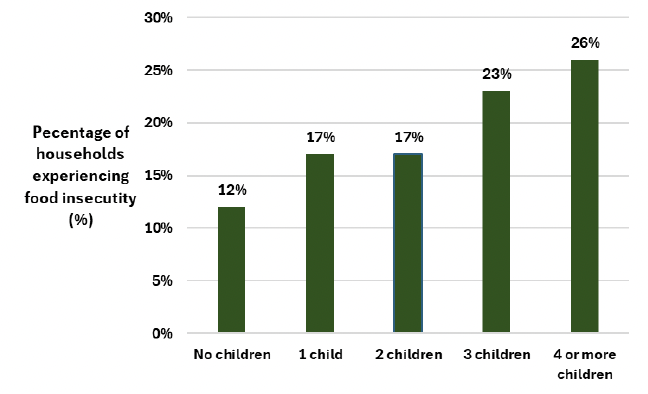

Larger households spend a higher proportion of their income on essentials and therefore have been more exposed to the increases in energy and food prices. Resolution Foundation research shows that larger families have frequently had to cut down on meals and resort to using food banks in response to the cost of living crisis[41]. Figure 6 below shows that 23% of families with 3 children experienced food insecurity, rising to 26% of families with 4 or more children[42].

Source: Food Foundation (2024)

The challenges associated with the additional costs experienced by larger households during the cost of living crisis are likely to have been compounded as a result of the UK Government’s two-child benefit limit.

3.6 Young people, students and young carers

There is increasing evidence to suggest that young people may have been adversely affected by the cost of living crisis. Older people (65+) in Scotland are less likely to say that they are managing less well financially (8% compared to 19% overall in December 2024).[43] Younger people are more likely to have reported that they ate less or skipped a meal[44].

There is emerging evidence that financial pressures are significantly affecting younger peoples health and wellbeing. The latest YouGov data from December 2024 shows that more than half (56%) of 18-34 year olds state that the cost of living situation has negatively impacted on their mental health compared to 24% of those aged 65+.[45]. This finding is also supported by recent evidence from the 2024 Understanding Scotland Economy Tracker.[46]

Research commissioned by the Higher Education Policy Institute found seven in ten students had considered dropping out of higher education since starting their degree and nearly two-fifths of those gave rising living costs as the main reason[47]. Research commissioned by the Russell Group of Universities[48] in 2023 found that 94% of students were concerned about the cost of living crisis, 72% of students felt that their mental health had suffered due to the cost of living and one in four students were regularly going without food or necessities because they could not afford them.

Caring comes with additional costs that can significantly affect a carer's financial situation. Research carried out with young carers in 2023 found that two thirds (66%) said the cost of living had affected them and their family.[49]

3.7 Lone parent and single person households

Lone parent households, which are more likely to be headed by women, are at a much higher risk of poverty than the average household and have the highest living costs relative to their net income of all household types. In 2017-20, they spent on average 46% of their income on fuel, food and housing[50]. Single adult households with children were nearly twice as likely to be food insecure (31%) than multi adult households with children (16%)[51]

Single person households are most at risk of destitution[52] and working-age adults are much more likely to need to turn to a food bank than pensioners. This is particularly the case for single adults living alone and those not currently in paid work[53].

3.8 Households in receipt of income related benefits, people narrowly ineligible for benefits and people with no recourse to public funds

The Cost of Living Crisis in Scotland Analytical Report[54] published in November 2022 had an extensive section on how households in receipt of income-related benefits were more likely to be disproportionately affected by the cost of living crisis. Much of that analysis rested on the fact that benefits had not been uprated to reflect current rates of inflation. To some extent that was addressed when the UK Government uprated working-age benefits in April 2023 in line with CPI inflation of 10.1%, and in April 2024 by the previous September’s CPI inflation figure of 6.7%. The UK Government also provided additional cost of living support payments to low income households in receipt of income related benefits and the Scottish Government increased the Scottish Child Payment (these interventions are discussed further in Chapter 4). Whilst these interventions have lessened the impact of the cost of living crisis they are unlikely to have fully compensated for the additional costs associated with high inflation and won’t have addressed the legacy of austerity which meant that many households entered the cost of living crisis from a starting point of financial hardship, with working-age benefits frozen or restricted for a number of years.

Over recent years there has also been increasing concern about the challenges faced by people during the cost of living crisis who have no recourse to public funds and who are unable to work.

Contact

Email: Tom.Lamplugh@gov.scot

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback