Understanding the Cost of Living Crisis in Scotland

This report draws together analysis from a wide range of sources to provide a summary overview of evidence on the cost of living crisis and its impact on Scotland. It includes evidence from Scotland and the UK as well as from other European countries.

6. The enduring legacy of the cost of living crisis in Scotland

While over recent months the rate of inflation has fallen to a level which is closer to the Bank of England’s target rate of 2%, the large increases in inflation over the last three years have effectively been ‘locked in’.

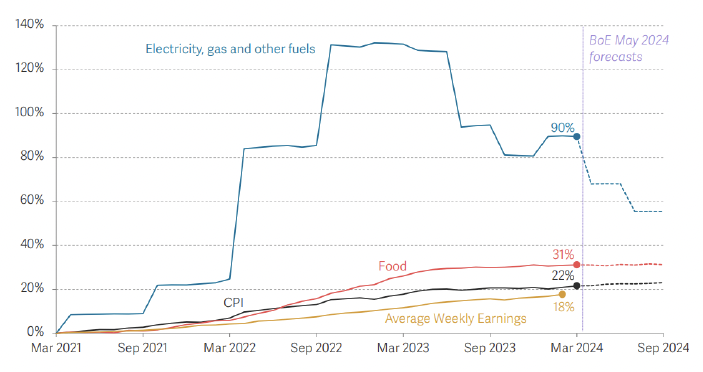

Figure 11 below shows that between March 2021 and March 2024 the cost of electricity, gas and other fuels had increased by 90% (although the energy price cap has subsequently been reduced) and the cost of food had increased by 31%, compared to an average increase in weekly earnings of 18%. As set out in Chapter 3 large rises in these essential components of CPI disproportionately affected certain low income household types.

Source: Resolution Foundation Analysis of ONS Consumer prices and Labour Market statistics; and Bank of England Monetary Policy Report, May 2024[95]

Data from ONS shows that the proportion of adults reporting increases to their cost of living (compared to the previous month) has gradually declined from 80% in October 2022, to 53% in October 2024[96]. Within Scotland, average pay growth has outpaced inflation for the last 18 months meaning that many households will have seen real terms improvements in living standards[97].

However, for many people it doesn’t feel like things are getting better and there is still a large proportion of the population who are managing less well financially. In Scotland the proportion of people ‘managing less well financially’ increased from 13% in November 2021 to 18% in January 2022 to 24% in March 2023 and has since reduced to 19% in December 2024[98]. The latest data from the Scottish Government Consumer Sentiment Indicator shows that at the end of 2024 consumer sentiment was weakening reflecting the financial and spending concerns and challenges that continue to face households[99].

People in Scotland are still concerned about the cost of living. Polling continues to show that the cost of living crisis remains high in the public consciousness and is an issue of significant and continued concern[100] [101]. The Office for National Statistics reported in November 2024 that people felt that the NHS (86%) and the Cost of Living (85%) were the most important issues facing the UK[102]. The cost of living was more likely to be reported as important by younger adults, women and those living in most deprived areas.

The crisis has resulted in some potentially longer term effects on people living in Scotland and these changes are discussed in the section below.

6.1 Changing profile of debt

While it is too early to understand the full impact of the cost of living crisis on levels and types of debt in Scotland, steep rises in the cost of living (not matched by rising incomes) have increased the scale of the debt problem by reducing financial resilience and negatively affecting household debt affordability.

In 2024 the Scottish Government published a review summarising evidence on the effects of the cost of living crisis on debt in Scotland[103]. It showed that an increasing proportion of households are struggling to pay bills and pay off debts as a result of cost of living increases. The review drew on evidence from a number of reports published since 2022 which showed increases in the average amount of unsecured debts and arrears owed by Scottish households. Furthermore, the review set out evidence from multiple sources to show that energy debt has increased during the cost of living crisis, as has council tax debt, types of consumer credit and borrowing from friends and family.

Demand for debt advice has increased since the start of the cost of living crisis. For example, data from StepChange shows a 30% rise in the number of clients completing a first full debt advice session between 2021 and 2023.[104] There is data to show that debt advice services, are dealing with increased numbers of clients and increasingly complex cases, both of which are adding to pressure on services, creating a backlog of cases and having a detrimental impact on debt advisers.[105] In 2023, the Poverty and Inequality Commission highlighted that:

“Episodes of acute crisis being experienced by clients of advice services is taking its toll on advisers, who, for some clients, are running out of support options to offer. As a consequence the negative impact on staff wellbeing is a huge issue for services”.[106]

6.2 Rising levels of food insecurity

The rising cost of food, and the wider effects of the cost of living crisis is likely to have led to higher levels of food insecurity. The Scottish Government tracks food insecurity through the Scottish Health Survey. Results from 2023[107] found that 14% of adults reported experiencing food insecurity, an increase from 9% in 2021 and the highest level since the time series began in 2017. Scottish Health Survey data shows that younger adults were more likely to experience food insecurity than older adults. The results also show that adults who experience food insecurity have below average life satisfaction and much lower mental wellbeing.

The latest polling data for the Scottish Government, from December 2024, found that 15% of Scottish households had cut back on essentials such as food in the last six months to help manage their household finances, rising to 45% of households who were managing less well financially. Although both of these figures have dropped in recent months from highs of 24% in February 2023 (for all households) and 62% (for those managing less well) there is evidence that people are struggling to afford enough food for their household as the quote below illustrates:

“My doctor has told me I need to eat more to put on weight, but I’ve got kids to feed so they have to come first.” (participant on the 2023 Scottish People’s Panel[108])

6.3 Widening inequality and high levels of poverty

Recent research in 2024 by Loughborough University on a Minimum Income Standard[109] for the UK found that for many people in the UK, including many people who are working, there continues to be a gap between what they have and what they need for a decent standard of living.[110]. The latest report set out that more people are falling well short of a Minimum Income Standard.

Analysis conducted by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation as part of their Poverty in Scotland 2023 report[111] found that just over 10% of workers in Scotland are locked in persistent low-pay (i.e. they are paid below the real Living Wage) and 72% of people within this group are women.

“There has been a shameful increase in the level of destitution in the UK, with a growing number of people struggling to afford to meet their most basic physical needs to stay warm, dry, clean and fed. This has deep and profound impacts on health, mental health and people’s prospects; it also puts strain on already overstretched services”[112].

Looking ahead, the 2024 Living Standards Outlook report[113] concludes that the outlook for poverty at the UK level is “bad” based on current policy assumptions and economic forecasts - low-incomes would be likely to fall in real terms and relative poverty would rise, especially for children, over the next UK Parliament.

“Incomes at the bottom of the distribution are projected to fall in each year of the Parliament, as things stand... households at the 10th and 20th income percentiles are set to be poorer in 2029-30 than in 2023-24”.

Largely driven by high energy prices the fuel poverty rate for Scotland has also increased, with an estimated 34% of households (861,000) in fuel poverty in 2023, of which 491,000 (19.4% of all households) are in extreme fuel poverty[114]. Both these figures reflect an increase from the 2019 estimated rates of 24.6% of households (613,000) in fuel poverty and 12.4% (311,000) in extreme fuel poverty.

6.4 Rises in acquisitive crimes and domestic abuse

Precisely disentangling the impact of the cost of living crisis on crime rates from other factors such as wider economic conditions, the Covid-19 pandemic, changes in population demographics and advances in technology is challenging.

However, there is some emerging evidence in Scotland to suggest that recent growth in overall recorded crime and Crimes of Dishonesty may be the result of cost of living pressures.[115] These increases are being driven by a large rise in shoplifting, up by 25% in the year ending September 2024, when compared to the previous year (from 33,789 to 42,271 crimes)[116].

Research also suggests that relative falls in the wages of low wage workers increases rates of property crime and violent crime. This finding has present-day relevance given recent real-term falls in wages as a result of the cost crisis. The academic evidence also tells us that increases in inequality and rates of poverty increase the rates of property crime and violent crime. However, it is not yet clear how these two economic variables are being affected by the cost crisis and therefore if, and how, they may impact upon crime. [117]

The cost of living crisis may result in higher instances of domestic abuse with Citizens Advice Scotland reporting in 2023 that demand for advice relating to domestic abuse has increased since the onset of the cost of living crisis[118].

6.5 Worsening mental and physical health

The extent to which changes in mental and physical health are directly attributable to the cost of living crisis is difficult to establish. However, polling data[119] from Scotland from December 2024 shows that 43% respondents have said that the cost of living has negatively affected their mental health and around a third of respondents have said it has negatively affected their physical health. These figures are considerably higher for people managing less well financially.

At points between May 2023 and March 2024 (May, August, December and March), survey data shows that around 40% of people agreed that food prices are limiting their ability to buy healthy foods for their household and one in seven are sometimes having to skip meals.

Among those managing less well financially, when last asked in March 2024, around seven in ten (71%) agreed that the price of food limits the extent to which they can buy healthy foods for their household currently and two fifths (39%) agreed that the price of food means that they can’t buy enough food for the household and they sometimes have to skip meals.

The cost of living crisis has increased the scale of the debt problem in Scotland. Studies on the impacts of different debt types all demonstrate the harmful health effects of problem debt, with evidence of multiple harms associated with consumer credit debt. However, recent evidence shows a particularly strong association between public and priority debt and poor mental health and as set out above both of these debt types have increased over the course of the cost of living crisis[120].

In September 2024 the Scottish Health Equity Research Unit published a report examining the state of Scotland’s health. It described the fact (as had been reported elsewhere) that life expectancy is no longer rising and average living standards have fallen since 2019. Compared to before the pandemic, more people in Scotland are in relative poverty; food insecurity, homelessness and fuel poverty; and the proportion of young adults not participating in work, education or training are all higher[121].

6.6 Worn down resilience and pessimism regarding the future

The cost of living crisis follows austerity-related cuts to welfare benefits and public services and the Covid-19 pandemic. These events have all affected the same groups of people and have also reduced the resilience and capacity of public services to respond to people’s needs[122]. In December 2024, only 23% of people living in Scotland were confident that there was financial help and support available for people who need it[123].

Despite a return to lower levels of inflation, there is ongoing pessimism in Scotland regarding the future. The latest Scottish Government polling showed that in December 2024 just 38% of people felt optimistic about the year ahead. Levels of optimism that things will get better soon have fluctuated over the course of the cost of living crisis (from a low of 27% in June 2022 to a high of 46% in January 2024). However, the figure has remained considerably lower (19% in December 2024) amongst those households saying they are managing less well financially. [124]

Contact

Email: Tom.Lamplugh@gov.scot

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback