Understanding extremism in Scotland: evidence review

A report which reviews evidence on defining extremism and the extent and nature of extremism in Scotland.

4. Exploring the prevalence of extremism in Scotland

The focus of this section will be on exploring what evidence exists in relation to the prevalence of extremism in Scotland, particularly in comparison with the rest of the UK, and the strengths and limitations of available sources. It will firstly outline some of the challenges with measuring extremism which have been discussed in the literature, before demonstrating how authors examining the extent of extremism across the UK have sought to overcome these difficulties through the use of 'proxy' measures. Similar measures that are available for Scotland, as well as additional research exploring the prevalence of intra-Christian sectarianism in Scotland, will then be reviewed. Finally, consideration will be given to where key gaps exist in relation to understanding the prevalence of extremism in Scotland.

4.1. The challenges involved in measuring extremism

Authors have noted that as well as being a challenging concept to define, extremism is also difficult to measure (Bartlette and Miller, 2012; Knight and Keatley, 2020; Schuurman, 2018). Bartlette and Miller (2012) argue that this in part stems from the definitional challenges surrounding the study of extremism, as without having a clear conception of what extremism is, it is difficult to determine what to assess. In addition, a lack of availability of relevant data has also been noted. For example, Knight and Keatley (2020) discuss how relevant information is rarely available in the public domain due to its sensitive nature, and note that the processes in place to protect individuals can create obstacles for data sharing between government departments and researchers who have the skills, resources and expertise to study this information.

Knight and Keatley (2020) also argue that where data is available, it often lacks specificity. For example, large datasets exist such as the Global Terrorism Database (GTD) and Profiles of Radicalisation in the United States (PIRUS). The GTD is an open-source database including information on global terrorist events from 1970 to 2020, while PIRUS contains deidentified individual-level information on the backgrounds, attributes, and radicalisation processes of over 2,200 extremists in the United States covering 1948-2018. However, these cover a range of different types of extremism (e.g., both violent and non-violent forms, inspired by a range of ideologies), as well as terrorism and radicalisation more broadly, and therefore lack the focus and detail that smaller datasets could provide (Knight and Keatley, 2020).

As noted in the methodology section, a resulting criticism levelled at research in this field is a lack of empirically grounded insight, with most studies relying on secondary sources and literature review-based methods. Schuurman (2018) suggests that research based on primary sources of data are 'the exception rather than the norm'.

4.2. Exploring the prevalence of extremism across the UK

As a result of these challenges, authors often rely on a range of 'proxy' measures of extremism to estimate its prevalence. An example of this approach is research undertaken by Bellis and Hardcastle (2019) who, in their report exploring the potential of public health approaches to preventing extremism, use various sources to understand the extent of extremism across the UK.

Bellis and Hardcastle (2019) firstly look at trends in terrorist attacks in the UK, using sources such as the Global Terrorism Index (GTI) (Institute of Economics and Peace (IEP), 2018), and data from Europol (2018) and the National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START) (2012). Key findings from these sources include that the 2018 Global Terrorism Index ranked the UK 28 out of 163 indexed countries in a score that describes the measurable impact of terrorism through attacks, fatalities, injuries and property damage, and that the UK was one of only five countries in Europe that saw an increase in terrorism in 2017 (IEP, 2018).

Bellis and Hardcastle (2019) also look at data on prosecutions for terrorism-related offences in England, Scotland and Wales, showing that there was a record high number of arrests for such offences in 2017, although arrests declined by 31% in the following year (Home Office, 2018b). They then examine the Prevent referral data for England and Wales (Home Office, 2018c), noting that 7,318 individuals were referred to Prevent in England and Wales between April 2017 and March 2018. The number of 'foreign fighters' (individuals who have travelled to conflict zones to engage in terrorist acts) from the UK is also examined using estimates from sources such as The Soufan Centre (Barrett, 2017) and the European Parliament (2018), which showed that the UK had been one of the largest sources of foreign fighters in Europe.

Finally, Bellis and Hardcastle (2019) look at public perceptions of extremism, reviewing a range of opinion polls which have explored support for extremist violence (e.g., BMG Research, 2017; YouGov, 2018), perceived security and levels of threat (YouGov, 2017; Ipsos MORI, 2017) among the UK population. They highlight that while these surveys suggest that the majority of the population condemn the use of violence, there is evidence which shows that between a fifth and a quarter of the British public understand why other people may be attracted to radicalism, and that levels of fascism may be increasing in the UK. In addition, they note that high levels of concern are expressed in the surveys about rising levels of extremism and the threat of future terrorist attacks in the UK.

Bellis and Hardcastle (2019) acknowledge the limitations of the sources they use; for example, the GTI overlooks unsuccessful, abandoned or disrupted terrorist attacks or ongoing and planned activity, while the extent to which extremism exists in communities, homes, institutions and other settings remains largely absent from academic literature. However, they argue that in the absence of more robust measures of extremism, data exploring criminal justice involvement and perceptions held by the general public offers at least some insight into the current reach and appeal of extremist ideals in the UK.

A similar approach is adopted by Redgrave et al. (2020) in their report reviewing the UK Government's approach to countering extremism. As with Bellis and Hardcastle (2019), Redgrave et al. (2020: 24) examine trends in terrorist activity in the UK, citing its 'close relationship to extremism'. To do so, they use data from Europol's (2018) European Union Terrorism Situation and Trend Report, Home Office (2020a) data on the number of individuals arrested for terrorism-related activity in the UK and Police Foundation (2020) data on deaths resulting from terrorism. They argue that this data shows that the most substantial terror threat in the UK is Islamist extremism, but note that there is also a growing threat from right-wing extremism.

Also in line with Bellis and Hardcastle (2019), Redgrave et al. (2020) look at the Prevent referral data for England and Wales (Home Office, 2020b), noting that there was a rise in referrals in the year ending March 2020 compared with the year ending March 2019. They also explore public attitudes data, including findings from a bespoke YouGov (2020a) survey which explored experiences and perceptions of extremism in the UK, as well as British Social Attitudes (BSA) survey and Eurobarometer survey data (NatCen, 2019; European Commission, 2019). Redgrave et al. (2020) argue that this data indicates that extremism is a growing problem in the UK, with key findings from the YouGov poll including that nearly a quarter (24%) of the public had experienced or witnessed extremism, and almost three-fifths (58%) believed that extremist behaviour had increased over the previous four years.

In addition to these sources, Redgrave et al. (2020) look at trends in the number of extremist protests and demonstrations in the UK, showing that attendance at far-right protests in particular had increased over the last decade (Bailey, 2020; 2014; Mulhall, 2019). They also look at estimates of the size of the membership of different groups involved in extremism based on information from the campaign group Hope Not Hate, but note limitations in this approach, including that such groups are not always structured in the manner of traditional membership-based organisations and that many exist entirely online.

Finally, Redgrave et al. (2020) look at trends in hate crime in the UK using police recorded statistics (Home Office, 2019a), the Crime Survey for England and Wales and data held by civil society organisations (Community Security Trust, 2019; Tell Mama, 2019). However, Redgrave et al. (2020) note some difficulties with using hate crime as an indicator of extremism; most significantly, that hate crimes are by no means always perpetrated by individuals with extremist views, whichever definition of extremism is relied upon. They also point to research which suggests that the individuals committing hate crime offences are unlikely to be the same individuals being referred to Prevent (START, 2012). However, Redgrave et al. (2020: 15) argue that in the absence of procedures and tools such as a police mechanism for flagging hate-related incidents and offences as extremist, it is a helpful measure when appropriate caveats are applied, as 'hate crime creates a permissive environment for extremism to flourish'. Overall, Redgrave et al. (2020) contend that the indicators they examine in their report suggest extremism is a growing problem in the UK.

A further report which brings together data available on a variety of proxy indicators to get a sense of the scale of extremism in the UK is that produced by the Commission for Countering Extremism (CCE)[2] (2019). The sources used in this report are in line with many discussed above, including Prevent referral data (Home Office, 2020b) and hate crime data for England and Wales (Home Office, 2019a). However, this report also looks specifically at data on offences involving 'stirring up' hatred based on race, religion or sexual orientation in England and Wales (Crown Prosecution Service, 2019). Estimates of social media sanctions are also explored, including YouTube channels removed for being hateful or abusive, content removed by Facebook for hateful speech, and accounts penalised by Twitter for hate conduct (CCE, 2019). The CCE (2019) argue that the measures they examine show that 'hateful extremism' is increasing in the UK.

4.3. Exploring the prevalence of extremism in Scotland

The above examples demonstrate how studies exploring the prevalence of extremism in the UK as a whole have typically brought together a range of sources to provide a broad understanding of its scale. The limitations of this approach, including the use of particular sources as proxy measures for extremism, are acknowledged.

The focus of the majority of studies identified was to assess the scale of extremism across the UK, and while some included data from Scotland (e.g., Bellis and Hardcastle (2019) look at arrests for terrorism-related offences in England, Scotland and Wales), more commonly the sources examined relate to England and Wales specifically. For example, discussion of the Prevent referrals in the reports produced by Bellis and Hardcastle (2019) and Redgrave et al. (2020) is focused on the England and Wales data published by the Home Office, and does not cover the Scotland data published annually by Police Scotland.[3]

Little research was identified for this review which focused exclusively on the extent of extremism in Scotland. However, many of the sources examined by Bellis and Hardcastle (2019), Redgrave et al. (2020) and the CCE (2019) to determine the prevalence of extremism in the UK include Scotland-specific data. The remainder of this section will therefore review these sources as well as additional evidence identified which explores the prevalence of sectarianism in Scotland, an issue which has been linked with extremism in the literature (Baker, 2017).

Terrorist activity

Firstly, the GTD can be examined. The GTD (2022) has a broad definition of terrorism that is wider than the legal definition of terrorism in the UK Terrorism Act 2000, covering 'the threatened or actual use of illegal force and violence by a non-state actor to attain a political, economic, religious, or social goal through fear, coercion, or intimidation'.[4] According to the GTD (2022) there were 5,513 incidents of terrorism in the UK between 1970-2020, 28 (<1%) of which took place in Scotland. The most prominent of these include the Lockerbie Bombing incident in 1988, when 270 people died after a Pan Am Passenger airline exploded over Lockerbie, and the incident at Glasgow Airport in 2007, when two individuals drove a jeep loaded with propane canisters into the glass doors of the terminal.

More recently, the GTD also includes the murder of Asad Shah, an Ahmadiyya Muslim shopkeeper who was attacked in Glasgow in 2016 by Tanveer Ahmed (a Sunni Muslim) because of his religious views. Though included in the GTD, Ahmed was charged and convicted of murder, not a Terrorism Act 2000 offence. The GTD also includes less high-profile incidents, such as when an explosive device was discovered and safely detonated in Edinburgh in 2018. An individual claimed responsibility for the device on an 'eco-terrorism' website, and identified as a member of the International Terrorist Mafia.[5] The vast majority of the other UK terrorist incidents over this period took place in Northern Ireland (4,705; 85%), while 759 (14%) took place in England and 21 (<1%) took place in Wales. Excluding incidents that took place in Northern Ireland, of the 808 incidents 94% took place in England, 3% took place in Scotland and 3% took place in Wales.

There is also evidence to suggest that the number of individuals who have travelled to engage in terrorism in other countries from Scotland is lower than other parts of the UK. It has been estimated that at least 850 British citizens have travelled to Iraq and Syria as 'foreign fighters' (Barrett, 2017, cited in Bellis and Hardcastle, 2019), but only two of these individuals travelled from Scotland specifically[6][7].

The Home Office publishes annual reports on arrests and prosecutions for terrorism-related offences in the UK. Although this includes data from Scotland no breakdowns by region are provided, meaning that the source cannot be used to look at arrests and prosecutions for terrorism-related offences in Scotland specifically, or to draw comparisons between Scotland and the rest of the UK. Overall, however, the above sources provide evidence which indicates that levels of terrorism may be lower in Scotland than in other parts of the UK, particularly England and Northern Ireland.

Prevent referral data

A further source which can be used to explore the prevalence of extremism in Scotland is the Prevent referral data. In Scotland, Police Scotland takes initial receipt of referrals to Prevent and thereafter coordinates a multi-agency response to safeguard the individual concerned (Police Scotland, 2023). As noted above the Scotland data is published annually by Police Scotland.[8] The England and Wales data is published annually by the Home Office, typically on the same date.[9]

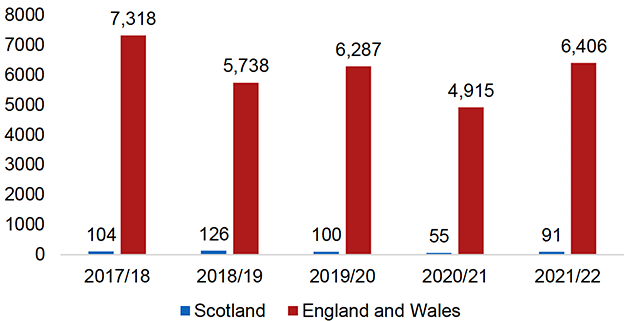

Figure 1 shows the total number of referrals in Scotland since 2017/18 compared with the total number of referrals in England and Wales, and shows that over this period there have been far fewer referrals made to Prevent in Scotland.[10] In the most recent year for which data is available (April 2021-March 2022) there were 91 referrals to Prevent in Scotland (Police Scotland, 2023) compared with 6,406 in England and Wales (Home Office, 2023).

Source: Police Scotland (2023), Home Office (2023)

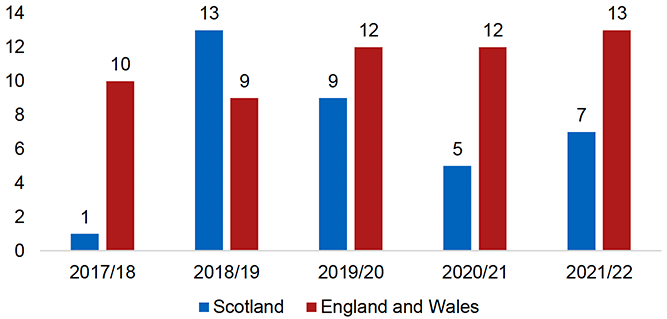

While the population of Scotland is significantly smaller than the combined population of England and Wales, Figure 2 shows referrals per million of the population in Scotland compared with England and Wales, and demonstrates that referrals also remain lower in Scotland when population size is taken into account.

Source: Police Scotland (2023), Home Office (2023)

However, although the total number of referrals to Prevent is lower in Scotland than in England and Wales, there are some similarities in the data. Figure 3 compares the number of referrals identified as suitable for Prevent per million of the population in Scotland and England and Wales since 2017/18. In Scotland, 'suitable for Prevent' refers to an individual being identified as suitable for the Prevent Multi-Agency Panel (PMAP) process, which involves using a multi-agency approach to assess the nature and extent of an individual's vulnerability and develop an appropriate support plan. This process is called 'Channel' in England and Wales. The figure shows that the number of referrals identified as suitable for Prevent relative to population size in Scotland and in England and Wales have been more comparable than total referrals, particularly in 2018/19 and 2019/20. This is because a lower proportion of referrals are identified as suitable for Prevent in England and Wales than in Scotland.

Source: Police Scotland (2023), Home Office (2023)

There are also similarities in the demographic characteristics of those referred to Prevent in Scotland and in England and Wales. In particular, the vast majority of those referred to Prevent in both Scotland and England and Wales are typically male, and the largest proportion of those referred tend to be aged between 15-20. There have also been similarities in the types of concern for which individuals have been referred to Prevent in Scotland and England and Wales in recent years, which will be covered in section 5 (exploring the nature of extremism in Scotland). Finally, the highest proportion of referrals typically come from the education sector and the police in both Scotland and England and Wales.

The Prevent referral data has limitations in relation to its use as a measure of the prevalence of extremism. In particular, the data only reflect individuals who have been brought to the attention of authorities through the referral system. There are a range of reasons why individuals who are susceptible to radicalisation might not be identified, for example due to individuals keeping their extremist views hidden. It is also important to note that not all individuals referred to Prevent are ultimately assessed as being vulnerable to radicalisation, with many signposted to other services or referred to other sectors for different forms of support, which should be borne in mind when considering figures relating to all referrals rather than just those who are deemed suitable for Prevent. The proportion of referrals not suitable for Prevent (either requiring no further action or being referred onwards) has broadly risen over time, from 44% in 2018/19 to 58% in 2021/22.

Thorton and Bouhana (2019) have also carried out research in England which suggested that thresholds for referrals are inherently discretionary and differ between local authorities, meaning that trends in the Prevent data may not reflect differences across the wider population. Caution must also be exercised when comparing the Scotland and England and Wales figures due to potential differences in reporting, recording and data management practices.

However, the data provides relevant insights, and show that while the total number of referrals is lower in Scotland than in England and Wales, the number of referrals relative to population size that are suitable for Prevent are more comparable. There are also similar patterns in the demographic characteristics of individuals referred between Scotland and England and Wales.

Public attitudes data

While some of the public attitudes surveys cited by Bellis and Hardcastle (2019), Redgrave et al. (2020) and the CCE (2019) focus specifically on England and Wales (e.g., YouGov, 2020), others are Britain-wide, and therefore include a small number of respondents from Scotland. The data can therefore be explored in further depth to gain some insight into views on the threat of extremism in Scotland.

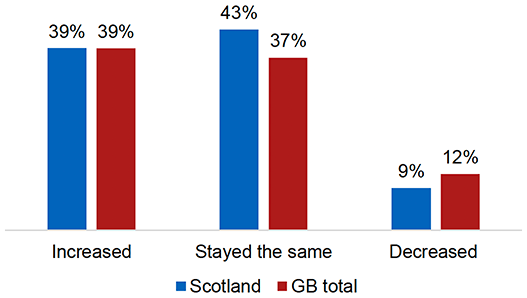

For example, a biennial poll conducted by YouGov looks at perceptions of the threat from terrorism in Britain over time, which Bellis and Hardcastle (2019) examine in their report. Figure 4 shows that in August 2022, almost two-fifths (39%) of respondents in Scotland thought the threat of terrorism in Britain had increased in the last five years, while over two-fifths (43%) thought it had stayed the same and one-tenth (9%) thought it had decreased (YouGov, 2022). These figures were similar to those for Britain as a whole, where almost two-fifths of respondents thought the threat had increased (39%), a comparable proportion felt the threat had stayed the same (37%), and just over one-tenth (12%) thought it had decreased (YouGov, 2022).

Source: YouGov (2022)

Base: Scotland (151), GB total (1759)

Looking at breakdowns by region in existing polls can therefore provide an insight into whether attitudes to terrorism and extremism in Scotland are in line with attitudes across Britain. However, no polls were identified which focused on issues more pertinent to the current evidence review, such as perceptions of the threat of extremism rather than terrorism, and personal experiences of extremism. Further, existing polls focus on views about Britain as a whole, meaning there is no scope to look at perceptions of the threat of terrorism and extremism in Scotland specifically. Additional caveats to note include that the Scotland sample in these polls is often very small, making it difficult to draw robust conclusions. Small sample sizes in Scotland also preclude more in-depth demographic breakdowns, for example by age or gender.

There is some attitudinal data available from the British Social Attitudes (BSA) survey, which overcomes some of the limitations associated with polls because it employs random probability sampling techniques and has a larger sample size than a typical poll (around 3000-4000 respondents, including 300-400 in Scotland).

Several questions on extremism have been included in the BSA survey. Most recently, in 2018 the survey asked respondents about their opinions on extremists holding public meetings and expressing their views on the internet or social media. As shown in Figures 5 and 6,[12] views on these issues were broadly comparable between Scotland and Britain as a whole, with most respondents believing that religious extremists should not be allowed to hold public meetings or publish their views on the internet or social media.

Source: BSA, 2018

Base: Scotland (135), GB total (1552)

Source: BSA, 2018

Base: Scotland (135), GB total (1552)

However, although BSA's sample size is bigger than the typical Scotland sample size in polls, it is still too small to undertake reliable subgroup analysis or to draw robust comparisons between Scotland and Britain as a whole. The BSA sample in Scotland also does not include any respondents in the Highlands and Islands. Further, while the issues covered in BSA are relevant to wider issues around extremism, they do not offer significant insight into the research questions being addressed by the present evidence review. Nonetheless, a tentative conclusion that can be drawn from the surveys examined is that perceptions of extremism and terrorism may be similar in Scotland to other parts of Britain.

Hate crime

An additional source of data that can be explored is that relating to hate crime. While the limitations of using hate crime as a proxy indicator for extremism are highlighted above, authors have argued that the two issues are closely related (Mills et al., 2015). For example, Mills et al. (2015) note that both hate crime and extremism can involve acts of violence and the targeting of individuals based on their perceived group membership.

A range of evidence is available in relation to hate crime in Scotland. In 2021 the Scottish Government published a study into the characteristics of hate crime in Scotland using police-recorded data. In this report, hate crime is defined as 'any crime which is perceived by the victim or any other person, to be motivated (wholly or partly) by malice and ill-will towards a social group' (Scottish Government, 2021a: 6). In Scotland, the law recognises hate crimes as crimes motivated by prejudice based on disability, race, religion, sexual orientation and transgender identity.

Limitations with police-recorded crime data are noted. For example, there are a range of factors that could influence the number of hate crimes recorded by the police, such as public reporting practices and attitudes to certain types of behaviour, which can change over time. Under-reporting of hate crime is also an issue, as different groups in society may be less likely to report hate crime to the police than others. These limitations mean that analysis of hate crime data can only inform us about the characteristics of hate crime that is reported to the police in Scotland, rather than the characteristics of all hate crime. Nonetheless, the report provides relevant insights into trends in police recorded hate crime in Scotland.

The report showed that in 2019/20, the police recorded 6,448 hate crimes in Scotland (Scottish Government, 2021a). Over three-fifths (62%) of those crimes included a race aggravator, 20% a sexual orientation aggravator, 8% a religion aggravator, 4% a disability aggravator and 1% a transgender identity aggravator. The remaining 5% had multiple hate aggravators. In contrast to England and Wales, where hate crime recorded by the police has increased over time (with the 105,090 recorded hate crimes in 2019/20 representing an increase of 8 per cent compared with 2018/19 (97,446) (Home Office, 2020c, cited in Redgrave et al., 2020), the number of hate crimes recorded annually by the police in Scotland has remained relatively stable, fluctuating between 6,300 and 7,000 (to the nearest 100) since 2014/15 (Scottish Government, 2021a).

The research also involved reviewing a random sample of hate crime recorded by the police in 2018-19 in greater depth, to provide more detailed information on the nature and characteristics of police-recorded hate crime in Scotland. Key findings include the observation that almost two-thirds (64%) of race-aggravated hate crimes had a victim from a visible minority ethnic (non-white) group, including 18% which had a victim of Pakistani ethnicity and 17% which had a victim of African, Caribbean or Black ethnicity. Further, in around two-fifths (42%) of religion-aggravated hate crimes the perpetrator showed prejudice towards the Catholic community; in a quarter (26%) of such crimes prejudice was shown towards the Muslim community; and in one in ten (12%) cases prejudice was towards the Protestant community. In the majority (94%) of sexual-orientation aggravated hate crimes the perpetrator showed prejudice towards the gay and lesbian community.

Further information on hate crime in Scotland is provided by the Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service (COPFS), who recently published details of hate crimes reported to COPFS in Scotland in 2021-22 (COPFS, 2022). The report covers crimes aggravated by race, religion, disability, sexual orientation and transgender identity. It showed that in 2021-22, the number of charges reported containing at least one element of hate crime was 5,640 in 2021-22, marginally less (-0.2%) than the 5,654 charges reported in 2020-21. Racial-aggravated crime was the most commonly reported hate crime, followed by sexual orientation-aggravated crime. There was a decrease in the number of charges reported to COPFS in 2021-22 compared to 2020-21 for race- and religion-aggravated hate crime, while sexual orientation-, disability- and transgender identity-aggravated hate crime charges saw an increase.

Finally, the Scottish Crime and Justice Survey (SCJS), an annual survey which asks people about their experiences and perceptions of crime in Scotland, also provides insight into trends in hate crime in Scotland (Scottish Government, 2021b). Although the SCJS does not ask directly about hate crime, at the most recent survey wave (2019/20) respondents who had experienced violent crime were asked if they believed the incident was, or might have been, motivated by a range of factors, including their ethnic origin/race, religion, sectarianism, gender/gender identity or perception of this, any disability/condition they have, sexual orientation, age, and pregnancy/maternity or perception of this. Over one in ten (12%) respondents believed an incident of violent crime they experienced was motivated by at least one of these factors, with the largest proportion (5%) believing it was motivated by their ethnic origin/race.

The above sources therefore show that while the number of hate crimes recorded by the police has stayed relatively stable since 2014/15, and there has recently been a marginal decrease in overall hate crime charges, hate crime remains a prominent issue in Scotland, with racially aggravated hate crimes the most common.

Research on sectarianism

A final source of evidence which can be explored in relation to the prevalence of extremism in Scotland is that relating to intra-Christian sectarianism. An Advisory Group on Tackling Sectarianism in Scotland was set up by the Scottish Government in 2012, to provide Scottish Ministers with impartial advice on how to develop and assess work to tackle intra-Christian sectarianism in Scotland. The Advisory Group defined sectarianism as:

'…a mixture of perceptions, attitudes, actions, and structures that involves overlooking, excluding, discriminating against or being abusive or violent towards others on the basis of their perceived Christian denominational background. This perception is always mixed with other factors such as, but not confined to, politics, football allegiance and national identity'. (Advisory Group on Tackling Sectarianism, 2015: 24)

As this definition emphasises, sectarianism is a complex phenomenon that covers a range of beliefs, behaviours and attitudes, some of which may be understood as forms of prejudice, discrimination and hatred. However, particular beliefs, attitudes and behaviours associated with sectarianism may also overlap with important elements of extremism, especially with regard to abuse or violence towards others on the basis of religious differences (Baker, 2017). Exploration of what existing research can tell us about sectarianism in Scotland therefore has relevance to the current evidence review.

A key aim of the Advisory Group on Tackling Sectarianism was to develop a body of empirical evidence on the nature, extent and impact of sectarianism in Scotland. The Advisory Group oversaw a range of research, including: a literature review, which examined existing evidence as well as undertaking analysis of the 2011 census, the Scottish Household Survey (SHS) and the SCJS (Scottish Government, 2013; 2015); a nationally-representative survey to collect information on public attitudes towards sectarianism (Hinchliffe et al., 2015); qualitative research in communities where sectarianism was perceived to exist, either currently or in the past (Scottish Government, 2016); and research into the community impact of public processions (Hamilton-Smith et al., 2015). In addition, further research on marches, parades and static demonstrations in Scotland has been carried out (Rosie, 2016), as well as survey research exploring the use of sectarian language on social media (Action on Sectarianism, 2017).

In 2015, the Advisory Group drew some key conclusions from the evidence base. Most significantly, they noted that there is evidence to indicate that pockets of sectarianism exist in Scotland, with the more violent and extreme forms concentrated in particular districts, towns and regions, in more impoverished areas, and in certain industries and workplaces. However, the Advisory Group (2015) also highlighted that that while a substantial body of evidence corroborates the perception that sectarianism is widespread and a real problem in Scotland, only a minority of people in Scotland appear to have been directly affected by it, and many have either not experienced sectarianism or can avoid it. The Advisory Group (2015) note that key gaps in our understanding of sectarianism in Scotland remain, particularly in relation to its form, character and extent, and highlight that a major challenge in the examination of sectarianism is the common recourse to 'anecdote and assumption' rather than robust research findings.

4.4. Summary

There are a range of sources which can be used to explore the extent of extremism in Scotland, including data relating to terrorist activity, Prevent referrals, public attitudes, hate crime and intra-Christian sectarianism. A tentative conclusion that can be drawn from this evidence is that the threat posed by extremism may look different in Scotland to other parts of the UK. For example, there appear to be lower levels of terrorism in Scotland, while Scotland faces unique challenges relating to sectarianism. Numbers of referrals to Prevent in Scotland are also lower, though there are similarities between the Scotland and England and Wales data, such as the demographic characteristics of those typically referred. However, while these sources provide relevant contextual information about issues closely related to extremism, a central issue with the material reviewed is that it does not look at the prevalence of extremism specifically, meaning evidence gaps remain.

Furthermore, a notable gap in the evidence relates to how recent crises, such as the COVID-19 pandemic and cost of living crisis, may have had an impact on the nature and prevalence of extremism in Scotland. Recent research has shown that some extremists have attempted to weaponise and exploit COVID-19, by using it as a means of spreading their ideologies through disinformation and conspiracy theories (Chapelan, 2021; Davies, 2021). However, no evidence exploring these trends in Scotland was identified for this review.

Contact

Email: SVT@gov.scot

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback