Understanding extremism in Scotland: evidence review

A report which reviews evidence on defining extremism and the extent and nature of extremism in Scotland.

5. Exploring the nature of extremism in Scotland

The focus of this section will be on exploring what evidence is available in relation to the nature of extremism in Scotland, including the most common forms of extremism, how this compares with the rest of the UK, and whether this has changed over time. It will firstly outline some of the challenges with measuring the nature of extremism, before exploring what existing data sources can inform us about the types of extremism that exist in Scotland and their prevalence, as well as the strengths and limitations of these sources. The section will conclude by considering where key gaps remain in relation to our understanding of the nature of extremism in Scotland.

5.1. Measuring the nature of extremism

The previous section demonstrated the challenges associated with measuring extremism, rising from the lack of consensus around the definition of the term, as well as a lack of availability of relevant data. This lack of consensus around definitions also presents difficulties when studying different types of extremism and their prevalence. Knight and Keatley (2020) give the example of three studies which sought to examine instances of lone actor terrorism in the UK, US and Europe over a similar timeframe. Due to different interpretations of what is meant by the term 'lone', as well as other parameters such as the nationality of the individuals and the threshold required for an event or incident to be considered 'terrorist', the sample sizes varied significantly between the three studies, hindering their comparability.

Knight and Keatley (2020) note that further difficulties arise when attempting to study the nature of extremism due to the small population of cases to study. For example, researchers seeking data to compare violent versus non-violent extremists, acting alone versus as part of a group, operating only in the UK, found only seven non-violent lone actors to include in their sample, meaning that the generalisability of their results was limited (Knight et al., 2017).

5.2. Exploring the nature of extremism in Scotland

Few papers were identified for this review that presented evidence relating to the nature of extremism in Scotland specifically. However, the sources reviewed in the previous section – including data relating to terrorist activity, the Prevent referral data, public attitudes data and research on intra-Christian sectarianism – provide relevant insights. In addition, a small body of work was identified which explores potential reasons why there appears to be less Islamist extremism in Scotland than in other parts of the UK, as well as some work exploring the reach of particular right-wing extremist groups in Scotland. The remainder of this section will therefore examine what findings from these sources suggest about extremism in Scotland.

Terrorist activity

The review identified a small number of sources focusing on the reach and impact of different forms of terrorism. This work mostly focused on the UK as a whole, the US, Eastern Europe, or Western countries more broadly (Alaimo, 2020; Collins, 2021; Doering et al., 2020; Knight et al., 2017; Michalski, 2019; Tin et al., 2022). For example, Michalski (2019) examined 8,000 terrorist attacks that had taken place in the UK and the USA between 1970 and 2017 using the GTD and classified them in terms of their ideological orientation and degree of lethality.

Michalski (2019) found that eight main categories of group could be identified from the incidents which had taken place in the UK and the USA. He classified these as: (1) animal rights or environmentalists; (2) nationalists or separatists; (3) leftists or Marxist groups; (4) protest groups opposing government policies, along with those designated as anarchists or anti-government agitators; (5) radical Islamist extremists; (6) right-wing religious extremists, racists, or hate groups; (7) anti-abortionists; and (8) promoters of sectarian violence. Michalski (2019) demonstrated that between 1970-2017 terrorism in the UK was largely driven by sectarian violence, with 92% of terrorist incidents linked to this category. However, Michalski (2019) also noted that in recent years there has been a shift in the predominance of particular types of terrorism, including an increase in Islamist and extreme right-wing attacks.

It is possible to examine instances of terrorist activity which have taken place in Scotland using Michalski's (2019) system of categorisation. As discussed in the previous section, according to the GTD (2022), 28 incidents of terrorism took place in Scotland between 1970-2020. Using Michalski's (2019) groupings, 4 (14%) of these were associated with nationalist or separatist groups, 4 (14%) were associated with sectarian violence, 2 (7%) were associated with right-wing religious extremists, racists or hate groups, 2 (7%) were associated with the radical Islamist extremist category, and 2 (7%) were associated with animal rights or environmentalist groups. In addition, 2 (7%) were associated with conspiracy theory extremists. For the remaining 12 (43%)[13] the ideology underpinning the incidents is unknown.

It therefore appears that of the groups Michalski (2019) discusses, those pursuing a nationalist or separatist ideology and promoters of sectarian violence have posed the biggest threat in Scotland since 1970, which differs to the picture across the UK. However, the small number of incidents that have taken place in Scotland over this period, and the fact that for most the underpinning ideology is unknown, mean that the inferences that can be drawn from this information are limited. Further, limitations of the GTD that were highlighted in the previous section remain relevant here, notably that this dataset does not cover unsuccessful, abandoned or disrupted terrorist attacks or ongoing and planned activity, and that it focuses on terror incidents rather than extremism more broadly.

Prevent referral data

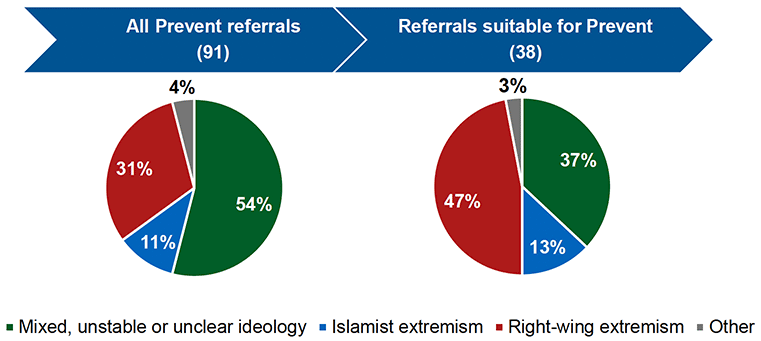

The Prevent referral data provides some insight into the nature of extremism in Scotland. In Scotland, referrals to Prevent are currently grouped into four categories: right-wing extremism, Islamist extremism, a mixed, unstable or unclear ideology,[14] and Islamist extremism. As noted in the previous section, in 2021/22 91 individuals were referred to Prevent in Scotland (Police Scotland, 2023). Figure 7 shows that of these 91 referrals the largest proportion were for concerns related to a mixed, unclear or unstable ideology (54%), followed by referrals related to right-wing extremism (31%). Of referrals identified as suitable for Prevent[15] (38), those related to right-wing extremism accounted for the largest proportion (47%).

Source: Police Scotland (2023)

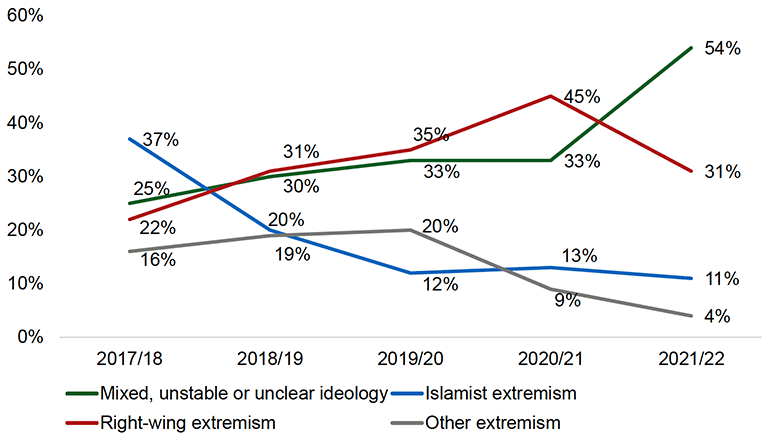

Figure 8 shows that since 2017/18, the proportion of referrals relating to a mixed, unstable or unclear ideology has risen from a quarter (25%) to more than half (54%) in 2021/22. This includes a steep increase of 21 percentage points between 2020/21 and 2021/22. The proportion of referrals relating to right-wing extremism rose from over a fifth (22%) in 2017/18 to 45% in 2020/21, before falling to under a third (31%) in 2021/22. The proportion of referrals relating to Islamist extremism fell between 2017/18 and 2019/20 (from 37% to 12%) and has remained broadly stable since. Having risen slightly from 16% in 2017/18 to 20% in 2019/20, the proportion of referrals relating to other types of extremism has since fallen to 4%.

Source: Police Scotland (2023)

Given that the Home Office publishes equivalent data on referrals to Prevent in England and Wales, comparing the Scotland data with the England and Wales data provides some indication of how comparable the nature of extremism may be between Scotland and elsewhere in the UK, although as noted in the previous section, caution must be exercised when using the Prevent data as a measure of extremism, and when drawing comparisons between the Scotland and England and Wales data due to different data management practices. In particular, it is possible that types of extremism could be coded differently by Police Scotland and the Home Office, especially in relation to the 'other' and 'mixed, unclear or unstable' groupings. In addition, since 2017/18 there have been changes in Police Scotland recording processes in relation to the 'other' and 'mixed, unstable or unclear' groupings, meaning that trends in the data should be interpreted with caution.

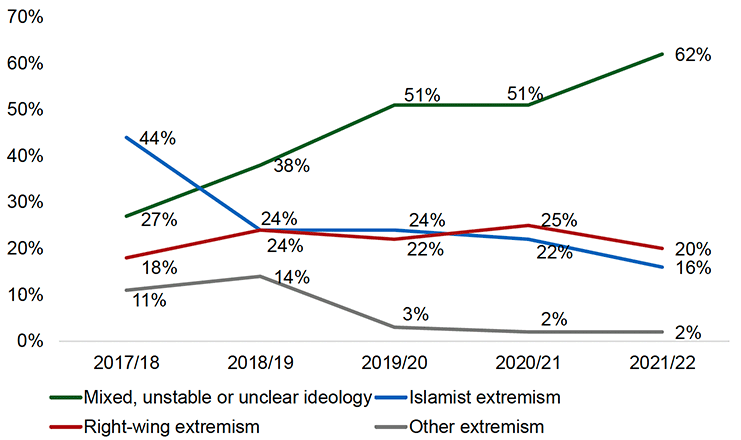

Nevertheless, comparing the data suggests that there may be some similarities in the trends relating to the types of concern for which individuals are referred to Prevent between Scotland and England and Wales. In particular, Figures 8 and 9 show that in both Scotland and England and Wales the proportion of individuals referred for concerns relating to a mixed, unstable or unclear ideology has risen over time, although this has increased at a faster rate in England and Wales than in Scotland. In both Scotland and England and Wales the mixed, unstable or unclear category accounted for the largest proportion of all referrals in 2021/22.[16]

The proportion of referrals relating to Islamist extremism has also fallen since 2017/18 in both Scotland and England and Wales, though it is notable that the proportion of referrals relating to Islamist extremism is typically lower in Scotland than it is in England and Wales.

However, the trend for right-wing extremism differs slightly between Scotland and England and Wales. In Scotland, the proportion of referrals relating to right-wing extremism increased between 2017/18 and 2020/21 before falling in 2021/22, while in England and Wales the proportion of referrals relating to right-wing extremism has remained more stable over this period.

Further, a key difference between the Scotland and England and Wales data is that in Scotland right-wing extremism has accounted for a much higher proportion of all referrals than Islamist extremism since 2018/19, while in England and Wales the proportion of referrals relating to right-wing and Islamist extremism have been broadly comparable.

Source: Home Office (2023)

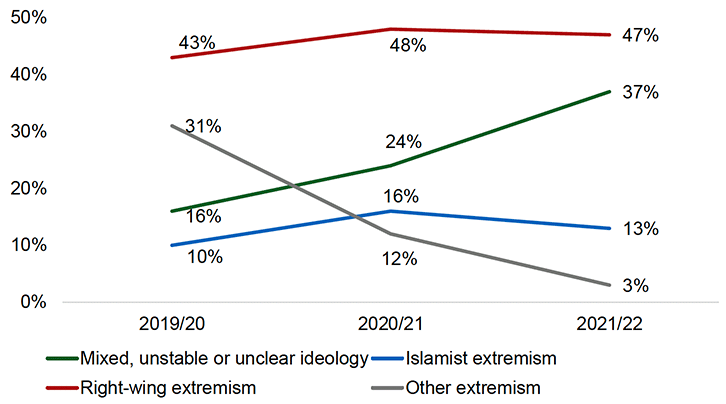

There are further similarities when looking at referrals identified as suitable for Prevent in Scotland and England and Wales. Figures 10 and 11 show that in both Scotland and England and Wales, individuals with concerns related to right-wing extremism tend to make up the largest proportion of referrals identified as suitable for Prevent, followed by those with a mixed, unclear or unstable ideology and those with concerns relating to Islamist extremism.

Source: Police Scotland (2023)

Source: Home Office (2023)

Overall, therefore, the Prevent referral data suggests that mixed, unstable and unclear ideologies are a growing source of referrals in Scotland. The proportion of referrals relating to mixed, unstable or unclear ideologies has also increased over time in England and Wales, but a key difference between the Scotland and England and Wales data is that in England and Wales right-wing extremism accounts for a lower proportion of referrals than in Scotland, while Islamist extremism accounts for a higher proportion. This is reflected in referrals relating to Islamist extremism accounting for a broadly similar proportion of referrals to right-wing extremism in England and Wales, whereas in Scotland the proportion of referrals relating to Islamist extremism is lower than right-wing extremism.

However, it should be noted that as well as having limitations as a measure of the prevalence of extremism, the Prevent data is also limited in what it demonstrates about the nature of extremism, as the overarching groupings used within Prevent reveal little about particular extremist groups and specific ideologies that individuals may have expressed an affiliation with. Further interrogation of the data would be required to explore the groups/ideologies which underpin the categories in more detail.

Public attitudes data

Some exploration of the nature of extremism can also be undertaken using public attitudes data. Attitudinal data is helpful for providing an understanding of people's perceptions of different types of extremism, including what threat they perceive to be greatest, as well as their experiences of different types of extremism. While no survey data on people's experiences of different types of extremism in Scotland was identified for this review, in 2021 YouGov undertook a Britain-wide poll which asked respondents how much of a threat they consider a range of types of groups to be, with a breakdown by region available (YouGov, 2021).

As shown in Figure 12, the survey indicated that people in Britain view the threat from Islamic extremists to be greatest, with 58% considering this to constitute a 'big' threat. Almost a third (31%) considered right-wing extremists to be a 'big' threat, and around a quarter considered Irish Republican and left-wing extremists to be a 'big' threat (24% and 23% respectively).

Source: YouGov

Base: GB total (1663)

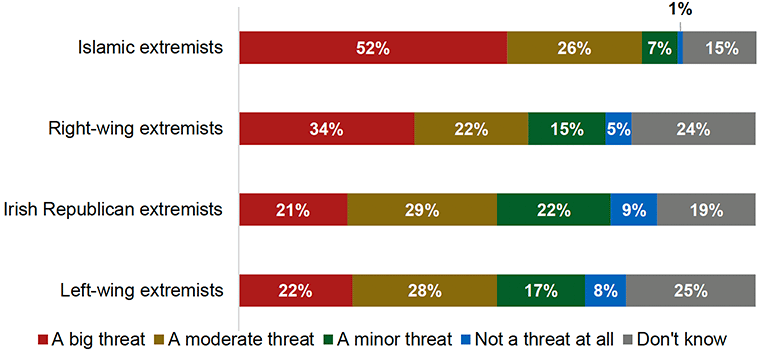

The results for Scotland were broadly in line with the findings for Britain as a whole. As shown in Figure 13, a slightly smaller proportion of respondents in Scotland considered the threat from Islamic extremists to be 'big' (52%). Around a third considered right-wing extremists to be a 'big' threat, while around a fifth considered Irish Republican and left-wing extremists to be a 'big' threat (21% and 22% respectively).

Source: YouGov

Base: Scotland total (122)

While there are some small differences in the distribution of responses, as discussed in the previous section, these may be the result of methodological issues such as the small sample size in Scotland rather than reflecting actual differences in attitudes between Scotland and Britain as a whole. However, it is notable that despite seemingly low levels of terror activity in Scotland (GTD, 2022), the perceived threat from both Islamist and right-wing extremists is considerable, with the majority of respondents in Scotland believing these groups to pose a big or moderate threat, and small minorities believing these groups to not pose a threat at all.

Research on sectarianism

Further evidence that can be explored in relation to the nature of extremism in Scotland relates to sectarianism. As discussed in the previous section, in 2012 an Advisory Group on Tackling Sectarianism commissioned a range of research on sectarianism, including a literature review (Scottish Government, 2013; 2015), public attitudes survey research (Hinchliffe et al., 2015) and qualitative research (Scottish Government, 2016; Hamilton-Smith et al., 2015). A key finding of this research was that sectarianism is perceived to be a serious problem in Scotland. For example, the survey research found a widespread perception that religious prejudice against Catholics and Protestants exists, with football being a commonly-mentioned contributory factor (Hinchliffe et al., 2015).

When asked about their own experiences, 14% of survey respondents said they had experienced some form of religious discrimination or exclusion at some point in their lives, with those who identified as Catholic more likely to say they had experienced some form of discrimination or exclusion based on their religion than those who identified as Protestant (Hinchliffe et al., 2015). Those who had experienced religious discrimination or exclusion as a result of sectarianism were more likely to be Catholic than any other religious group.

The Advisory Group (2015) concluded from the research that experiences of sectarianism appear to be more common among Catholics, and that there remain pockets of sectarianism, with more violent and extreme forms often concentrated in areas with higher levels of deprivation. Overall, however, a minority of people in Scotland have been directly affected. The Advisory Group (2015) highlighted that there remain some key areas in which there is a lack of robust knowledge about the nature and extent of sectarianism in Scotland.

Research on Islamist extremism

An additional source identified for this review was a limited body of evidence which has sought to explore potential reasons as to why there appears to be less Islamist extremism in Scotland than other parts of the UK (Bonino, 2016). A small number of studies have discussed potential reasons why both the number of terror incidents related to Islamist extremism in Scotland (GTD, 2022), and the number of individuals from Scotland who have travelled to Syria and Iraq to engage in terrorist activity, are lower than other parts of the UK.

In this literature, a range of reasons are put forward to explain why fewer instances of Islamist extremism have occurred in Scotland than elsewhere. The first is that the Muslim population in Scotland may have a comparatively stronger attachment to Scottish identity than Muslims in England and Wales do to English or Welsh identity (Bonino, 2016). For example, results from the 2011 Census showed that 40% of Muslims in Scotland described their national identity as Scottish (either exclusively or in combination with British or another identity), while only 16% of Muslims in England described their national identity as English and 15% of Muslims in Wales described their national identity as Welsh.

Bonino (2016) argues that a potential reason for this is that Muslim communities in Scotland are well integrated, particularly in comparison with the rest of the UK, citing qualitative research undertaken by Homes et al., (2010) which showed that both Muslims and non-Muslims in Scotland perceived integration in Scotland to be easier than in England. This was attributed to three main factors: smaller numbers of Muslims, less fear of terrorist attacks and particular aspects of living in Scotland (e.g., people in Scotland were seen as typically friendly, open and straightforward). Further, survey research examining the attitudes of Muslims and non-Muslims towards integration in Scotland undertaken by Homes et al. (2010) found that the majority of respondents agreed that 'most Muslims in Scotland are integrated into Scottish life'. Bonino (2016) also points to the small size of the Muslim population in Scotland as a factor which enhances integration, as well as suggesting that ethnic segregation is not as widespread in Scotland as it is in major cities in England and Wales.

Qualitative research undertaken by Choudhury and Fenwick (2011) also explored the impact of counter-terrorism measures on Muslim communities across the UK. Choudry and Fenwick (2011) carried out focus groups with Muslims living in Glasgow, and found that the stance taken by the Scottish Government and police in challenging the use of powers under s44 of the Terrorism Act 2000 to stop and search individuals in designated locations by the British Transport Police was viewed positively by participants, and contributed to an overall sense that the impact of counterterrorism policing and policies were different in Scotland compared with the rest of Britain.

It has also been suggested that Islamophobia is a less prevalent issue in Scotland than it is elsewhere in the UK (Bonino, 2016). For example, Hussain and Miller (2006) used BSA and Scottish Social Attitudes (SSA) survey data to compare levels of Islamophobia in Scotland and England. Exploring respondents' attitudes towards Muslisms, they found that while Islamophobia existed in Scotland, its prevalence was higher in England.

Overall, therefore, there appear to be several reasons why the prevalence of Islamist extremism may be lower in Scotland than other parts of the UK. However, it is important to highlight the limitations of this evidence; notably, that the number of studies on this subject is small, much of the data are now dated, and the work by Bonino (2016) was not based on primary research.

Reach of right-wing extremist groups

Finally, some information is also available regarding the membership and reach of particular right-wing extremist groups in Scotland. The campaign group Hope Not Hate produces annual reports on the state of right-wing extremism in the UK. Their most recent report, published in 2022, indicated that several extreme right groups have active branches in Scotland. Most significantly, they noted that at the time of writing, the Scottish branch of Patriotic Alternative (PA), a far-right white nationalist group, had recently carried out canvassing, displayed banners and held events in Scotland, including their second annual conference in Stirling in October 2022 (Hope Not Hate, 2022). Hope Not Hate (2022) stated that PA's Scottish branch was 'its most active, hardline and independent'.

Notably, however, since the publication of this report Patriotic Alternative have undergone a split, with members of PA forming a new group named the 'Homeland Party'. That the organiser is based in Scotland and that most of the Scottish branch has become part of the group has led Hope Not Hate to state that 'while the Homeland Party is a UK-wide organisation, Scotland is undoubtedly a key region of strength at present'.[19]

Other extreme right groups identified as having a Scottish presence include: Blood & Honour (B&H), who organised a concert in Scotland in October 2021; Britain First (BF) and the British Freedom Party (BFP), who carried out campaigning in Scotland in the run up to the 2021 Scottish Parliament election; and Identity Scotland, who carried out postering, leafleting and a banner drop in Scotland in 2021 (Hope Not Hate, 2022). In previous reports, Hope Not Hate have also noted groups including the British National Socialist Movement, Proud Boys, and Combat 18 as having active units in Scotland (Hope Not Hate, 2021, 2020).

Overall, there is evidence to suggest that some extreme right-wing groups have gained traction in Scotland. However, the focus of Hope Not Hate is on right-wing extremism specifically, and limited evidence was identified for this review looking at the reach of particular extremist groups relating to other ideologies. This evidence cannot therefore be taken to suggest that the extreme right is a more prominent form of extremism in Scotland than other types of extremist ideology.

Further, while looking at the reach of particular extremist groups provides useful insights, there is evidence to indicate that both Islamist and right-wing extremists have moved away from formal group structures in recent years, and now embrace a looser and more 'light-touch' model of association based on prominent influencers and known group identities (Redgrave et al., 2020). For example, Redgrave et al. (2020) note that two of the most prominent extreme right-wing attackers in recent years, Brenton Tarrant (Christchurch, New Zealand) and Darren Osborne (Finsbury Park, London), were radicalised online and were not members of formal groups.

5.3. Summary

In summary, there is some data available which can be used to explore the nature of extremism in Scotland, including data on terrorist activity, Prevent referral data, public attitudes data, and research on intra-Christian sectarianism, Islamist extremism and right-wing extremism. These sources provide some indication of the types of extremism which may be more and less prevalent in Scotland, as well as allowing some tentative comparisons with the rest of the UK to be drawn. In particular, as noted in the previous section it appears that mixed, unstable and unclear ideologies are a growing issue in Scotland, a trend also apparent in other parts of the UK. There is also evidence to suggest that the prevalence of Islamist extremism could be lower in Scotland, but that Scotland also faces distinct issues relating to intra-Christian sectarianism. However, each source reviewed has limitations in its use as a measure for examining the nature of extremism in Scotland, meaning that evidence gaps remain.

Contact

Email: SVT@gov.scot

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback