Vaping and smoking among Scottish adolescents

This report presents results for Scotland from the ASH SmokeFree GB Youth survey to provide a picture of underage smoking and vaping behaviours

Key findings

Use of vapes, cigarettes and related products

Vaping and smoking prevalence

In 2024, 18.8% of those aged 11-17 said they had tried vaping, including 10% who only tried a vape once or twice and 7.4% who identified as current vapers (4.6% regular vapers – vaping more than once a week – and 2.8% occasional vapers).

16.6% of the sample said they had tried smoking, including 6.9% who only tried smoking once and 4.4% who identified as current smokers (1.3% regular smokers – smoking once a week or more – and 3.1% occasional smokers).

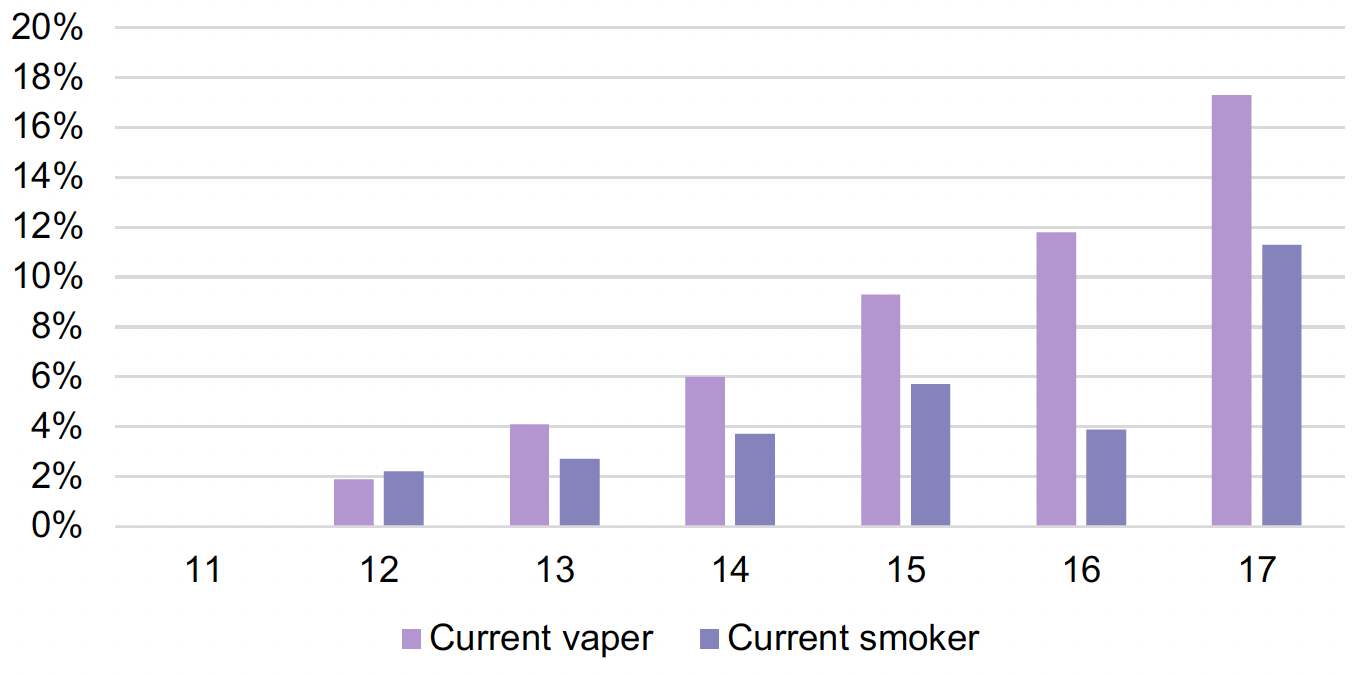

Both ever and current use of vapes and cigarettes generally increased with age (see Table 1 and Figure 1).

Ever use of vapes was more frequent in girls compared to boys (22.4% vs 15.6%).

A small percentage (3%) of all those aged 11-17 reported ever use of nicotine pouches (i.e. tobacco-free oral products to be placed between lip and gum for nicotine absorption) and 5.1% ever use of shisha (i.e. water pipe used to heat tobacco usually mixed with herbs or flavourings).

| Status | All % | 11 % | 12 % | 13 % | 14 % | 15 % | 16 % | 17 % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ever vaper | 18.8 | 0.0* | 7.1* | 16.6 | 18.8 | 25.1 | 27.9* | 33.3* |

| Current vaper | 7.4 | 0.0* | 1.9* | 4.1 | 6.0 | 9.3 | 11.8 | 17.3* |

| Ever smoker | 16.6 | 8.9 | 9.2* | 15.0 | 13.7 | 19.9 | 20.6 | 28.0* |

| Current smoker | 4.4 | 0.0 | 2.2 | 2.7 | 3.7 | 5.7 | 3.9 | 11.3* |

| Unweighted base (count) | 677 | 47 | 98 | 104 | 87 | 122 | 104 | 115 |

Order of use

Ever vapers (N=137) were asked about order of use of vapes and cigarettes. In 2024, due to concerns about the wording of the question in past waves – mentioning “real cigarette” and possibly implying that vapes are a type of cigarette, respondents were split in half: one group answered the old question and the other a new question mentioning “tobacco cigarette” instead.

In the first group (N=69), 34.9% said they tried smoking a real cigarette before vaping and 19% that they tried a vape before a real cigarette. In the second group (N=68), 34.6% said they tried smoking a tobacco cigarette before vaping and 21.7% that they tried a vape before a tobacco cigarette.

Given the small base and similar percentages, no significant difference due to wording was identified. Results are indicative and cannot be used to establish causality.

Products

Awareness of products

Among all 11-17 year olds, awareness of vapes was high (92.4%), while only about two fifths had heard of other nicotine products such as nicotine pouches (37.9%) and shisha (40.5%).

Source of products

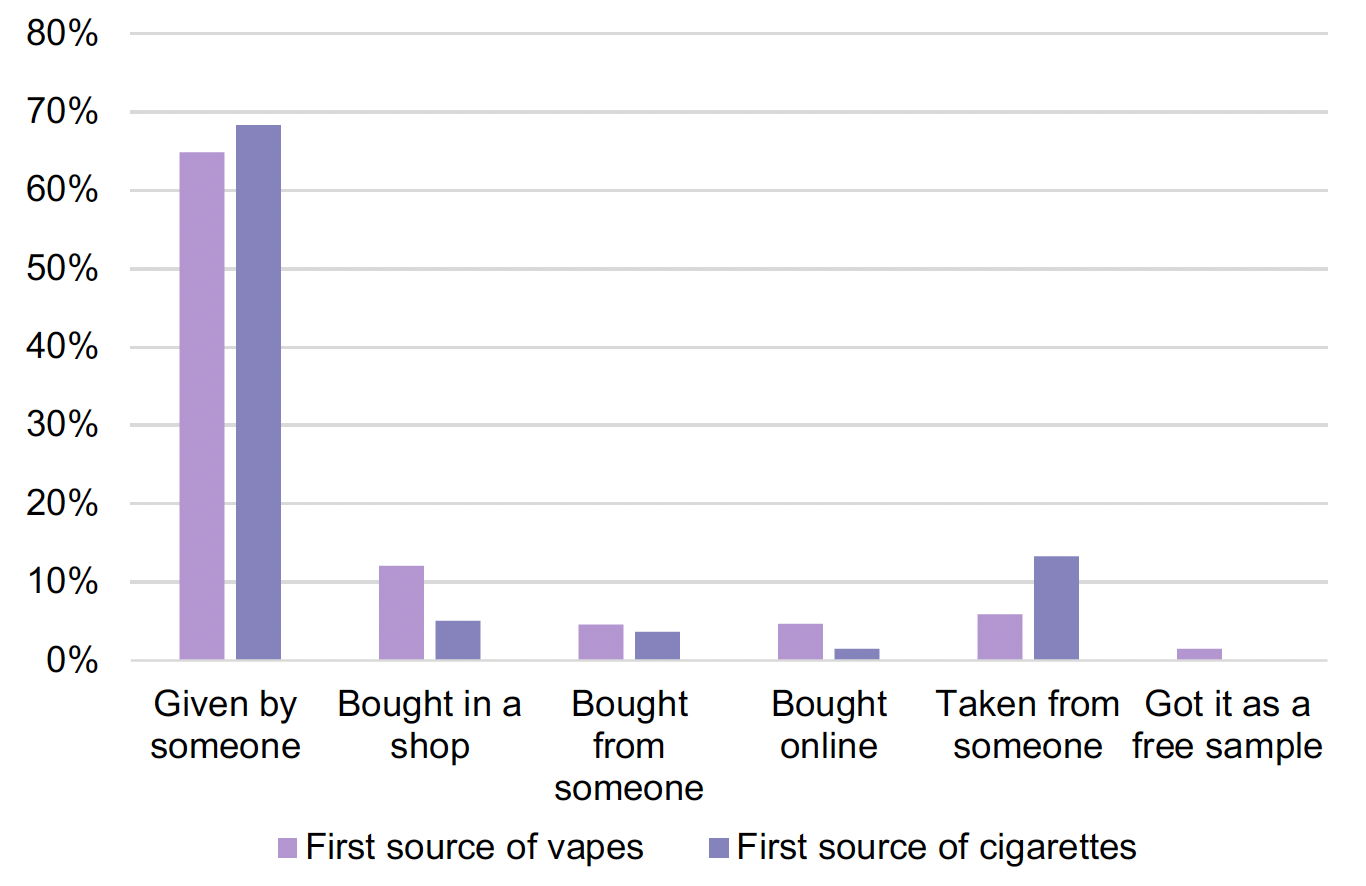

Access to vapes and cigarettes is primarily through informal routes rather than purchasing from an outlet (see Figure 2).

Of all the adolescents who tried vaping, 64.8% said their first vape was given to them by someone they know (59.8% by a friend; 5% by a relative). 21.4% purchased the vape (12.1% in a shop; 4.6% from another person and 4.7% online). 5.9% took the vape from someone and 1.5% were given one as a free sample by a vape company.

Of all the adolescents who tried smoking, 68.3% said their first cigarette was given to them by someone they know, mostly by a friend (63.1%) and much less by a relative (5.2%). One in ten (10.3%) purchased the cigarettes, mostly from a shop (5.1%) or from another person (3.7%), while only a small proportion bought them online (1.5%). 13.3% took the cigarette from someone.

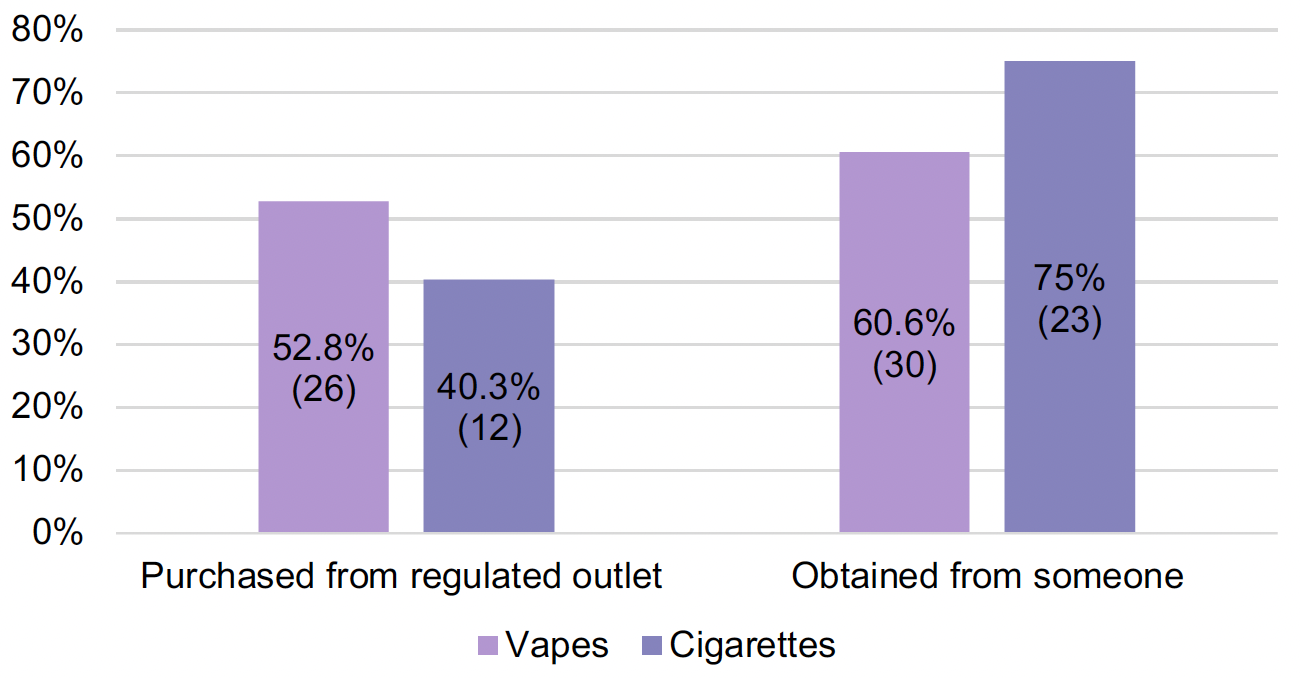

Over half (52.8%) of current vapers and 40.3% of current smokers (12 out of 32) purchase their products from a regulated outlet (supermarket; newsagent, corner shop, tobacconist or off-licence; petrol station or garage shop; street market; vape or other type of shop). More commonly, vapes and cigarettes are obtained informally from someone, either bought or given, by 60.6% of current vapers and 75% of current smokers (23 out of 32).

Figure 3 presents results on sources of products with percentages alongside counts. These should be treated with caution as base numbers are very small.

Type of products

Disposables are the most popular type of vapes. Among ever vapers, 74.5% said they have ever used a disposable. Among current vapers (N=54), 61.8% said a disposable vape is the type of device they use most often (vs 28.2% saying they mostly use a rechargeable type).

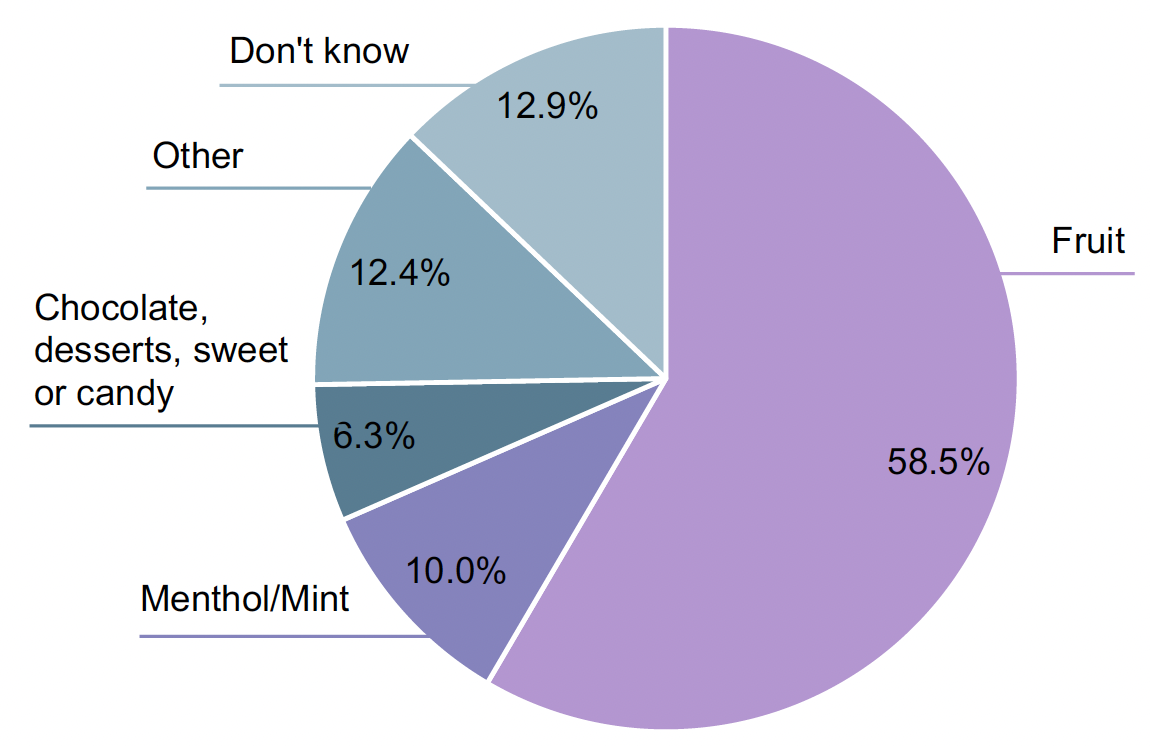

Around half of current users reported use of ice e-liquids (49.5%). When asked about the flavour used most often, the majority said they choose fruit flavours (58.5%), followed by menthol/mint (10%) and chocolate, desserts, sweet or candy flavour (6.3%) (see Figure 4).

44.1% of current and ex-vapers said the most common strength of nicotine used was 20mg/ml (2%).

Although the base is small (N=32), the data suggest that current smokers mostly use ready-made cigarettes (14 out of 32), or a combination of ready-made and hand-rolled cigarettes (13 out of 32). A small number (3 out of 32) said they only smoke hand-rolled cigarettes.

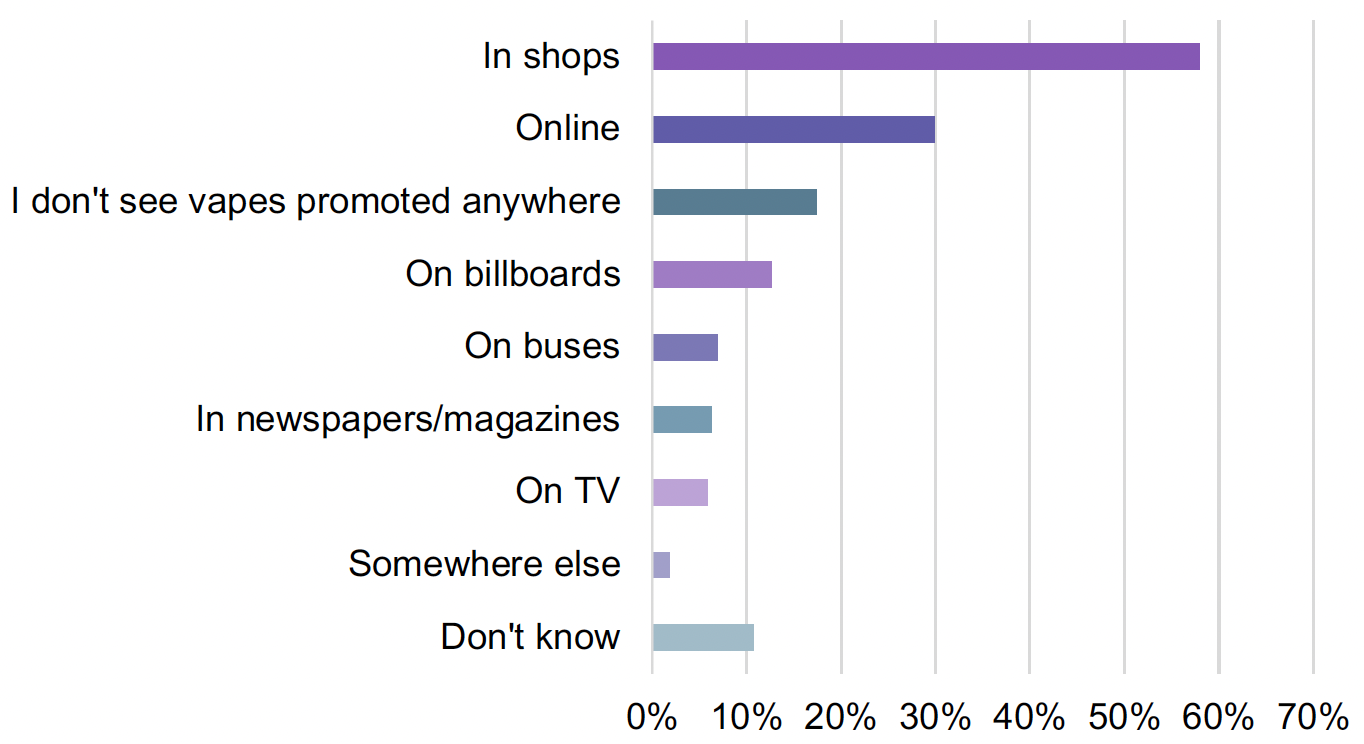

Advertising

Among those aware of vapes, more than half of adolescents aged 11-17 (57.9%) said they were exposed to advertising in shops. Almost a third (29.9%) said they saw vapes promoted online, 12.6% on billboards and 6.9% on buses (see Figure 5).

For shops, exposure to advertising was higher in corner shops compared to supermarkets.

Among those aware of vapes and going into corner shops (85.2% of respondents), 52.4% said they notice vapes on display every time/most times and 25.3% said they see them sometimes. This compares to 28.1% and 32.6% respectively among those aware of vapes and going into supermarkets (89.9% of respondents).

Among all those who go into corner shops (91.9% of respondents), 31.6% said they notice cigarettes on display every time/most times and 23.7% said they see them sometimes. This compares to 15.1% and 20.4% respectively among all those who go into supermarkets (96.9% of respondents).

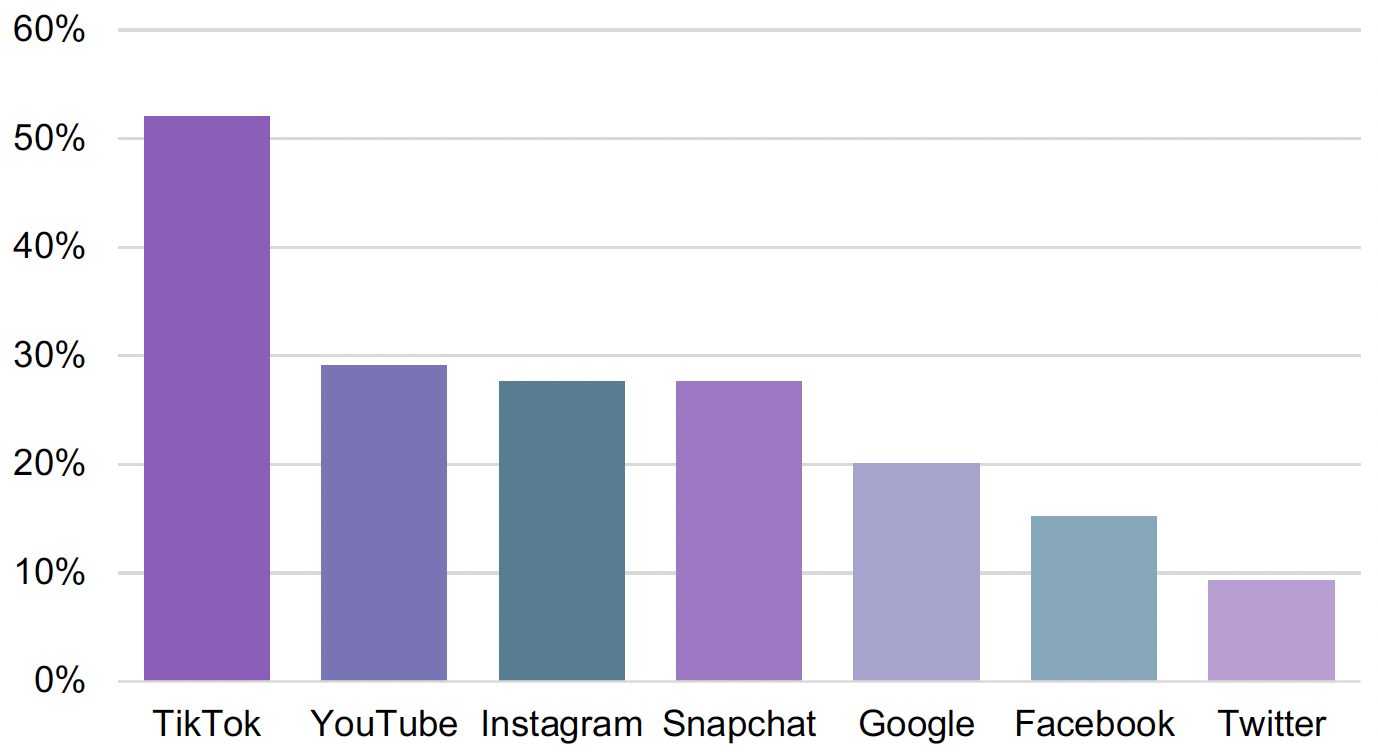

Social media advertising represents the main channel through which adolescents are exposed to promotion of vapes online. Among those who saw vapes being promoted online, the majority (51.6%) said they saw them promoted on TikTok compared to 29.1% on YouTube, 27.6% on Instagram and 27.6% on Snapchat (see Figure 6).

Experiences and views

Reasons for vaping

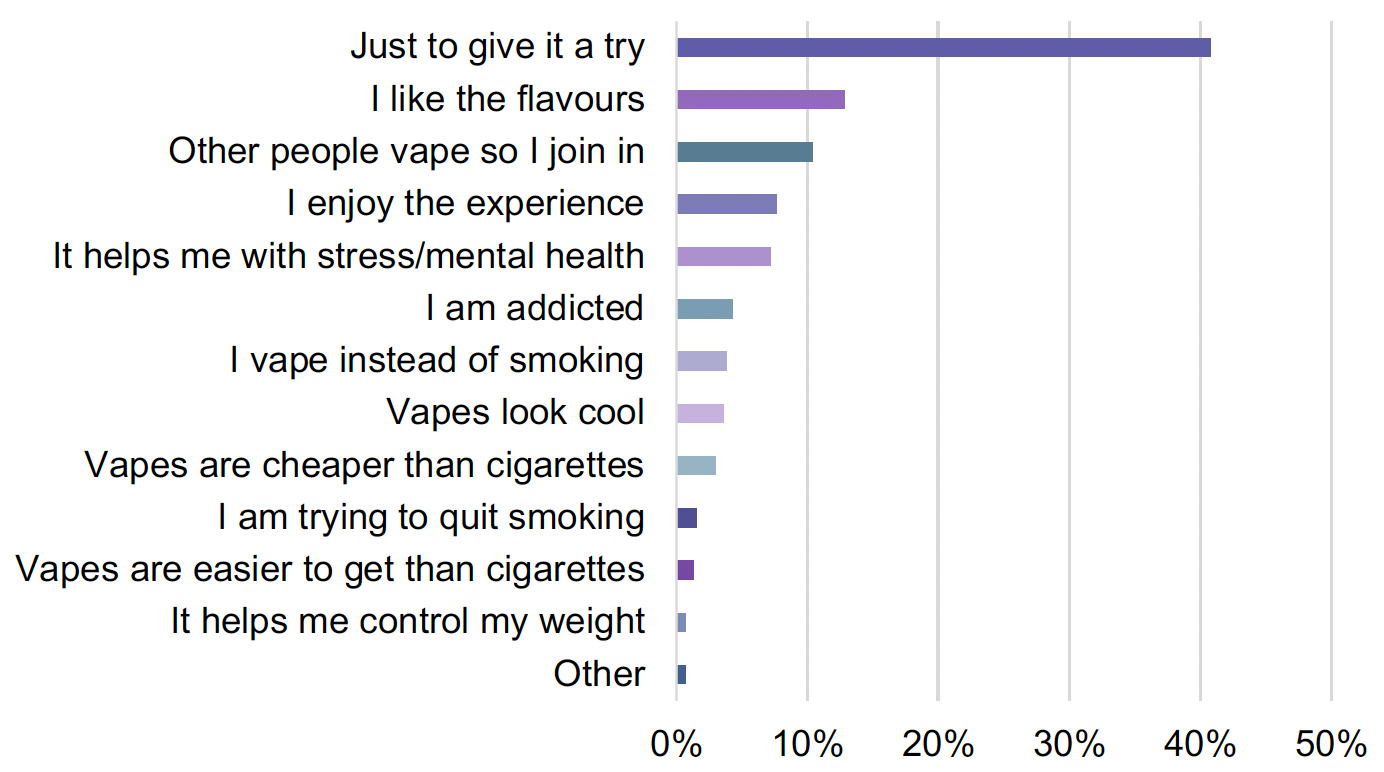

Curiosity constitutes a main driver of ever use of vapes, with the majority of those who have tried vapes saying they just wanted to give it a try (40.8%). Other main reasons for trying vapes were: appeal of flavours (12.8%), peer influence (10.4%), enjoyment (7.6%) and stress management (7.2%) (see Figure 7).

Health harms of vaping

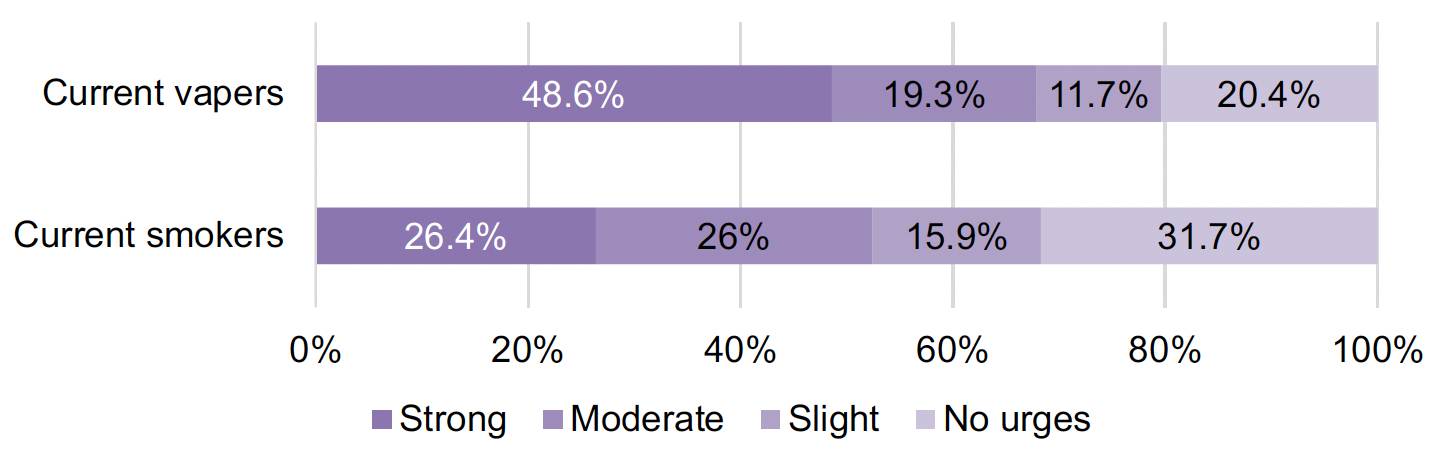

The majority of current vapers considered themselves addicted (67.4% vs 26% who said they were not) and described their urge to vape as moderate to strong (67.9%).

Conversely, the majority of current smokers (17 out of 32) did not think they were addicted (vs 10 who said they were). However, half of them (16 out of 32) described their urge to smoke as moderate or strong. Caution is advised in interpreting these results due to the small base (see Figure 8).

A substantial percentage of ever vapers (60.9%) said they experienced some form of side effect from vaping. Main harms reported were cough (40.4%), throat irritation/sore throat (29.5%), nausea (26.3%), light headedness (24.2%), chest irritation/breathing problems (19.8%), headache (18.8%) and a loss of sense of taste (12.2%) (see Table 2).

| Reported effect | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Cough | 40.4% |

| Throat irritation/sore throat | 29.5% |

| Nausea/feeling sick | 26.3% |

| Light headedness/breathing problems | 24.2% |

| Chest irritation/breathing problems | 19.8% |

| Headache | 18.8% |

| Loss of sense of taste | 12.2% |

| Mouth irritation (e.g. lips/mouth hurt or were sore) | 9.3% |

| Other side effect | 1.6% |

| Net: any effect | 60.9% |

| No side effect experienced | 24.6% |

| Don’t know/Don’t want to say/Skipped | 14.4% |

A majority (58.2%) of all those aged 11-17 who had heard of vapes wrongly believed that vaping is more or equally harmful than smoking (10.8% more harmful and 47.5% about the same). Only 29.4% said that vaping is less harmful than smoking.

Quitting

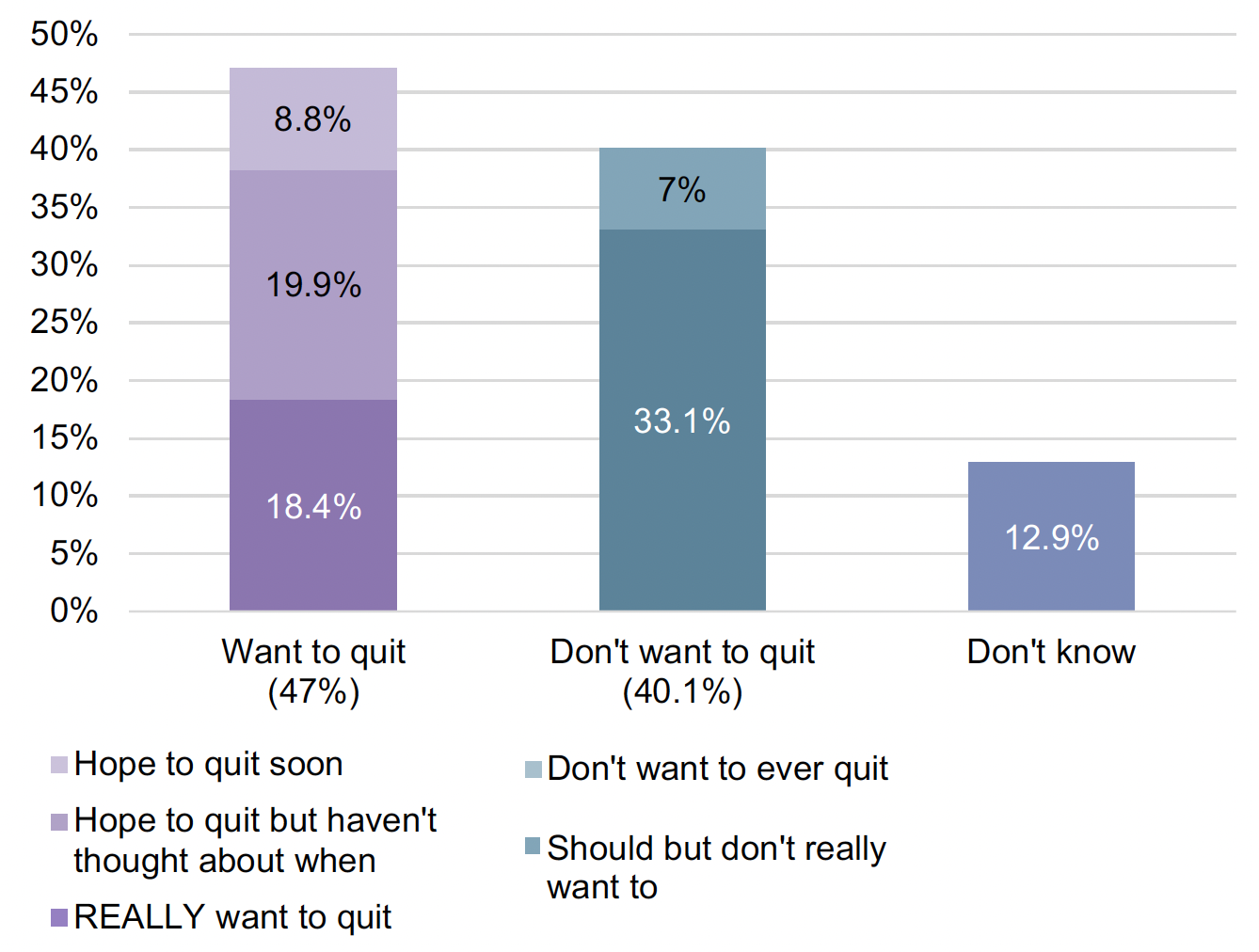

Current vapers aged 11-17 were asked about their willingness to quit vaping.

Nearly half (47%) said they want to stop vaping, including 21.5% who indicated they really want to. Two fifths (40.1%) said they don’t want to stop vaping, including 33.1% who said that they think they should stop vaping but don’t really want to, and 7% who said that they don’t want to ever stop vaping (see Figure 9).

Current smokers aged 11-17 were also asked about their willingness to quit smoking. Results are reported below but they should be interpreted with caution given the small base (N=32).

Nearly half (14 out of 32) said they want to stop smoking, including 5 respondents who indicated they really want to. 12 respondents said they think they should stop smoking but don’t really want to, and one respondent said that they don’t want to ever stop smoking.

Among ever smokers (N=118), 58.2% agreed that if they could go back in time, they wouldn’t have started smoking.

Second-hand smoke

About one in ten adolescents reported being exposed to second-hand smoke.

8.9% of all those aged 11-17 said people are allowed to smoke inside their home/house.

11.5% said that they have travelled in a car in which someone was smoking. This tended to be occasional (10.1%) rather than most days or every day (1.4%).

Views on policy options

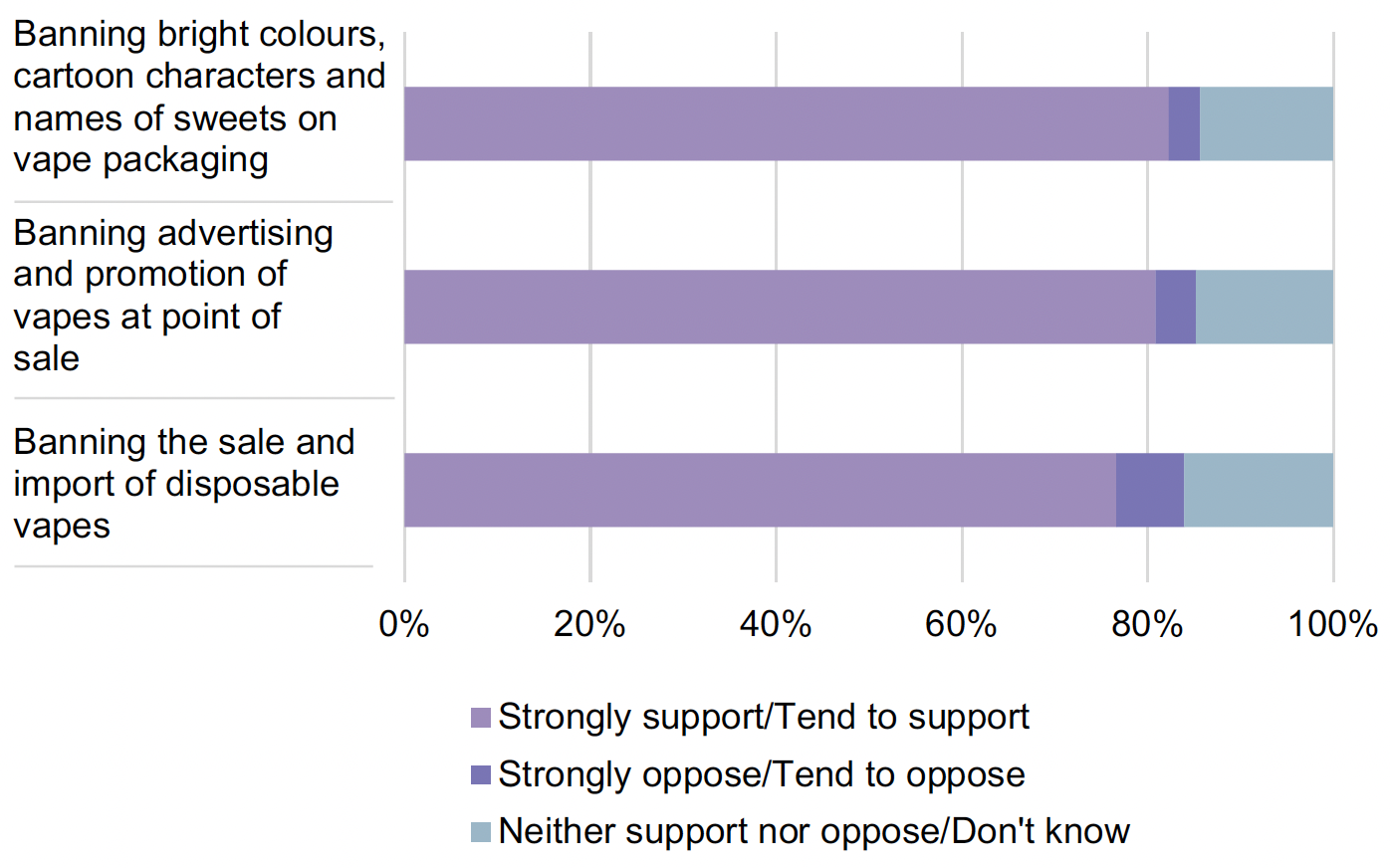

The majority of all those aged 11-17 supported policy measures to reduce vaping: 82.3% supported a ban of bright colours, cartoon characters and names of sweets on vape packaging, 80.9% a ban of advertising and promotion of vapes at point of sale (at the till, in store and as people enter shops) and 76.6% a ban of the sale and import of disposable vapes (see Figure 10).

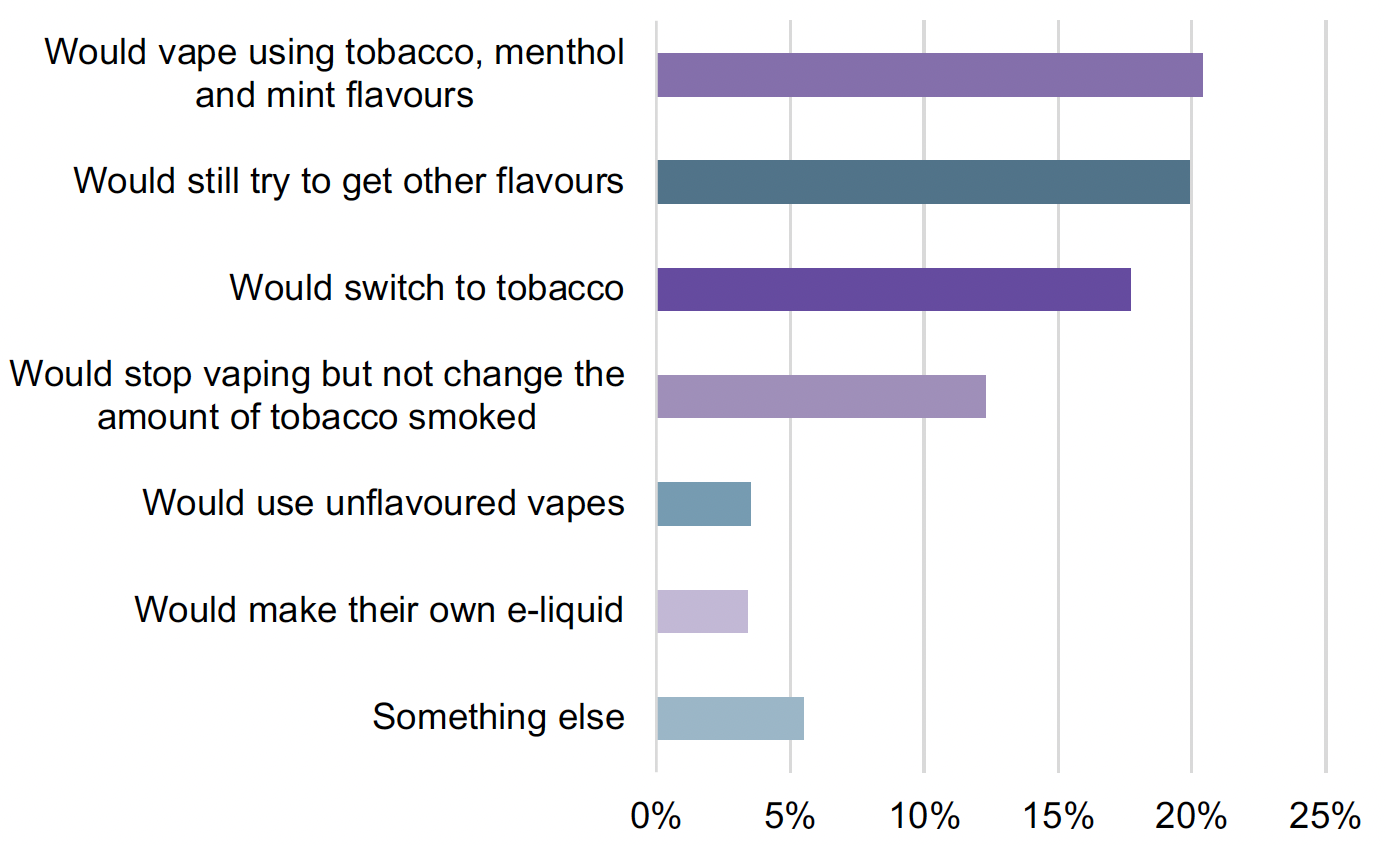

Current vapers were also asked how they would change their vaping behaviours if only tobacco, menthol and mint flavours were available (respondents could select more than one option). The most popular responses were that they would vape using these flavours (20.4%) and that they would still try to get other flavours (19.9%). Just over a tenth (12.3%) said they would stop vaping but not change the amount of tobacco smoked. Around a fifth (17.7%) indicated they would switch to tobacco (either smoke more of it, start smoking it or go back to smoking it) (see Figure 11).

Among those who mainly use disposable vapes, 14 out of 34 said they would start using a reusable type of vape if disposables were not available. 7 out of 34 said they would still try to get disposable vapes in some way. However, with such a small base, caution is advised when interpreting these results.

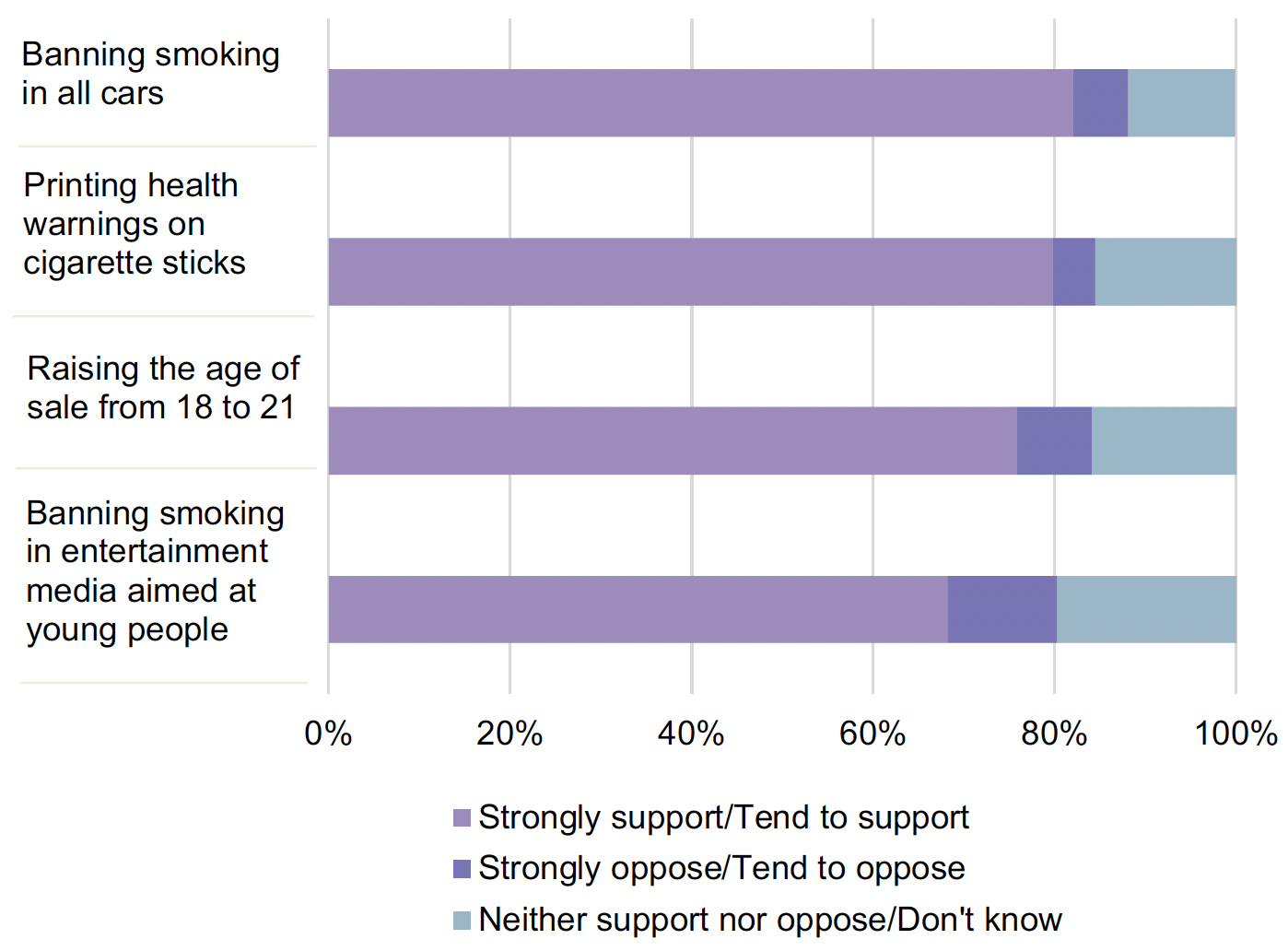

Among all respondents aged 11-17, 47.4% said Government’s activities to limit tobacco smoking are not enough. The majority (67.7%) supported the recently announced legislation to raise the age of sale for tobacco for those born in 2009 or later by one year, every year, so that it will be never legal to sell them tobacco. Support was also high for banning smoking in all cars (82%), printing health warnings on cigarette sticks to encourage smokers to quit (79.8%), raising the age of sale from 18 to 21 for tobacco (75.8%) and excluding smoking in entertainment media aimed at young people (e.g. films for under 18s or music videos) (68.2%). These results are reported in Figure 12 below.

How to access background or source data

The data collected for this social research publication:

☐ are available in more detail through Scottish Neighbourhood Statistics

☐ are available via an alternative route.

☐ may be made available on request, subject to consideration of legal and ethical factors.

☒ cannot be made available by Scottish Government for further analysis as Scottish Government is not the data controller.

Contact

Email: socialresearch@gov.scot

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback