Welfare outcomes for livestock transported on Northern Isles ferry routes

This report from Scotland's Rural College (SRUC) explores the welfare outcomes for livestock transported on the Northern Isles ferry routes and aims to provide objective evidence on the behavioural responses of cattle and sheep to ferry transport from the Northern Isles to Aberdeen.

Objective 2: Historical data and modelling

Animal journey length

Reports on animal movements involving cattle and sheep departing the Northern Isles were prepared by staff at the University of Glasgow and EPIC. Data for cattle were summarised for 2022 and for sheep between 2011 and 2022.

Cattle:

Number of journeys per animal: 26,948 cattle moved off Orkney or Shetland to the mainland during 2022. Of these, 14,662 experienced one journey in order to reach the mainland (directly from Orkney or Shetland to the mainland), 11,218 experienced two journeys (one within Orkney or Shetland and one to the mainland) and the remaining 596 experienced between three and six journeys, with the last being to the mainland. The interval between journeys is unknown, except that they occurred within 2022, and the number of journeys after reaching the destination on the mainland is also unknown.

Distance travelled per animal: The predominant final destination for cattle was Aberdeenshire and Angus. The straight-line distance between CPH of origin and CPH of destination on the UK mainland was: Cattle from Orkney to Aberdeenshire (median 123 miles, interquartile range 113-130 miles); cattle from Orkney to Angus (median 155, interquartile range 154-159 miles), cattle from Shetland to Aberdeenshire (median 204, interquartile range 189-214). No cattle from Shetland were delivered directly to Angus.

Sheep:

Number of journeys per animal: The EPIC data combined journeys that occurred within 7 days into a single journey, thus it is not possible to determine how many sheep were transported again within a few days of arrival at their first off-island destination. Around 30% of animals moved to a different holding more than 7 days after arrival.

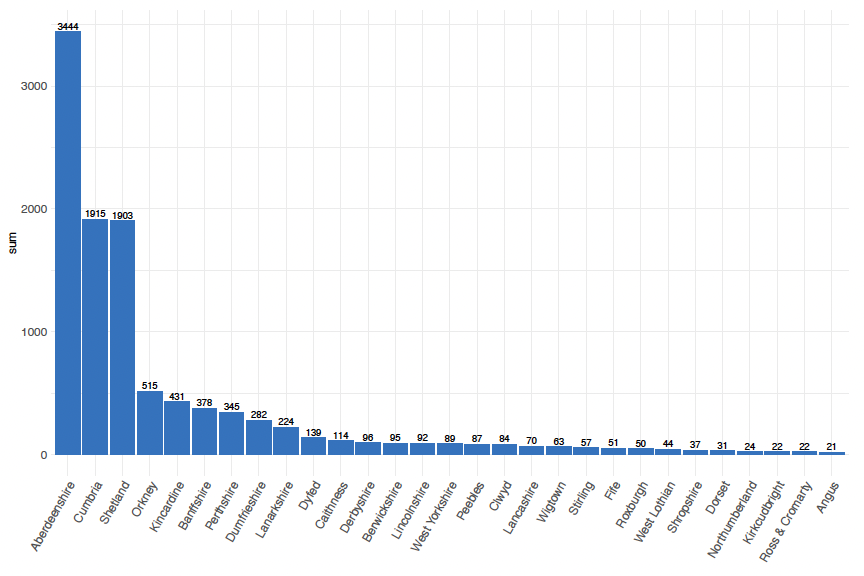

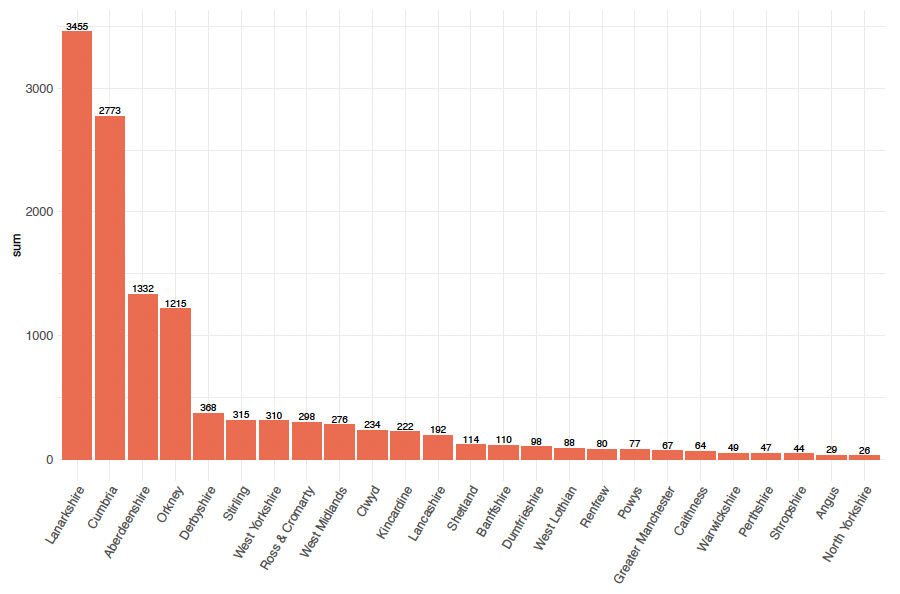

Distance travelled per animal: Around 60-65% of sheep batches leaving the Northern Isles journeyed to another farm in Scotland, with around 20% sent to a market, and the remaining percentage being sent to abattoirs, to holdings in England or other premises. The large majority of movements occurred in the autumn. Data were analysed for 2022 in more detail, during which 126,613 sheep left Shetland and 67,111 sheep left Orkney. For sheep leaving Shetland, the large majority of animals were destined for Aberdeenshire or Cumbria or another of the Shetland islands, with much smaller numbers traveling elsewhere in Scotland or to England or Wales (Figure 1). The primary off-island destinations for sheep from Orkney were Lanarkshire, Cumbria and Aberdeenshire, again with smaller numbers destined for elsewhere in Scotland, England or Wales (Figure 2). The port lairage in Lerwick is a critical control point and visible in the movement data. The majority of sheep arrived at their destination within one day of leaving the lairage in Lerwick, although the period of time from leaving the farm of origin to departing the Lerwick lairage is likely to be an additional 10-12 hours in most instances.

Official Veterinarian inspections in abattoirs

Official Veterinarians in two abattoirs within approximately 40 miles of Aberdeen kindly noted the date, hour of arrival, number of animals in the consignment, and whether animals appeared unusually (a) tired or (b) thirsty or hungry on arrival compared to animals arriving from elsewhere (based on subjective impression).

Observations were made on 523 cattle over 20 days (2 abattoirs) and 114 sheep over 4 days (1 abattoir). Cattle that had experienced a ferry journey appeared more tired than animals from other sources on two observation days and hungrier on one day. They showed normal levels of thirst on all observation days. Sheep appeared to be moving slower than animals from other sources on one observation day. They showed a normal level of tiredness on the remaining three days and showed normal levels of thirst on all four days. Wave data for the corresponding dates (minimum and maximum significant wave height and swell height) showed that the days when animals appeared to deviate in behaviour from the norm were not unusual with respect to sea conditions. The predominant wave direction on the dates with abnormal behaviour was from the SW, corresponding to the prevailing wind direction.

This is potentially a valuable source of data, but the quantity of data collected for the purposes of the current study is extremely limited, especially for sheep considering the number of animals transported by ferry during a season. Sheep were also not observed immediately upon arrival at the abattoir. This is a form of data collection that the Scottish Government may wish to continue collecting, together with data on duration since leaving the farm of origin to determine whether abnormal behaviour most likely reflects lack of rest or the sea conditions.

Historical data from animal inspections on arrival in Aberdeen

We explored whether there was any evidence in historical data for an effect of sea conditions on animal casualties evident on arrival in Aberdeen. Casualty data was provided by Aberdeen City Council which holds responsibility for inspection of the port lairage facility. Seven complete years of data plus two years represented by only 3 months each were available, beginning in 2014. Data were filtered to remove inspection visits when fewer than 100 animals were observed. The original inspection notes were not designed to attribute causation of health problems to the journey versus farm of origin. Therefore, ascribing cause was challenging in our analysis and is not without error. It was assumed that any animal which was unable to walk out of a cassette, was dead-on-arrival or needed to be euthanised on arrival was a casualty of the journey. Animals with obvious pre-existing conditions (e.g. poor body condition, pregnancy) were not included as casualties of the journey. Some cases were ambiguous (lameness which did not prevent onward travel; prolapse). These could have existed before loading into the cassettes and these animals were not counted as casualties of the journey. On almost all journeys with a casualty, only one animal was affected rather than multiple animals. Therefore, the occurrence of casualty animals was treated as a binary outcome (yes/no) rather than as a proportion of the animals observed.

Significant wave height (Hs) data were taken from the Centre for Environment, Fisheries and Aquaculture Science (CEFAS) database. As the closest wave recording station to the ferry journeys, wave height was taken from the Claymore buoy owned by UK Oil and Gas Ltd located 161km NE of Aberdeen in the Claymore oil field. Wave height was recorded at midnight on the morning of the day of inspection, approximately when vessels would be at their closest point to this buoy.

A total of 299,060 animals passed through the Aberdeen port lairage during days in which inspection visits were made and on which wave height data were available. The number of casualties that could be attributed to the journey with reasonable confidence was 23 (0.0008% of animals transported). The median significant wave height on journeys with no casualties was 1.80m and that during journeys with casualties was 1.90m. A Mann Whitney U test showed that these medians were not statistically significantly different from chance (p=0.26).

It should be noted that this analysis was significantly limited in a number of respects: Health outcomes that were not deemed severe enough to warrant recording by inspectors may have occurred but are not visible in the data (e.g. lameness that did not require intervention). The wave data from the Claymore buoy was the only retrospective data available for analysis and is not located directly on the journey from Shetland and is a significant distance off-route from Orkney. Furthermore, it provides only a snap-shot of one part of the journey and the effects of wave height are likely to be influenced by other metrics (e.g. wave direction and period; swell height, direction and period; vessel speed and heading).

Contact

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback