Withdrawal of the 'Coronavirus (COVID-19): use of face coverings in social care settings including adult care homes' guidance: Equality Impact Assessment

This equality impact assessment (EQIA) considers the potential effects of withdrawing the 'Coronavirus (COVID-19): use of face coverings in social care settings including adult care homes' guidance on those with protected characteristics.

Stage 2: Data and evidence gathering, involvement and consultation

Include here the results of your evidence gathering (including framing exercise), including qualitative and quantitative data and the source of that information, whether national statistics, surveys or consultations with relevant equality groups.

The table below considers the evidence / data as well as potential differential impacts for the protected characteristic groups.

Age

Background

Social care users:

Social care users are more likely to be significantly older than the median of the Scottish population and are more likely to have long-term health conditions and/or disability. They may be particularly vulnerable to COVID-19 and more likely to have complex co-morbidities which place them at greater risk of complications if they contract COVID-19. They are also more likely to be worried about their health and the risks of contracting COVID-19, and are more likely to experience loneliness and be negatively affected by routine face mask wearing.

Social care staff:

The median age of the social care workforce is 43 which is comparable with the median age for the total Scottish population aged 16 and over (49 years) and the median age for those between 16 and 65 years old (the traditional working age population) in Scotland (41 years).

Evidence / data

There is a clear relationship between long-term health conditions or disability and increasing age. In 2020, the Scottish Health Survey found that the prevalence of any long-term condition increased with age, from 32% among those aged 16-44, to 68% among those aged 75 and over.

Long-term health conditions, disability, and age are all associated with increased likelihood of needing care and support and the likelihood of needing social care increases with age; in 2020/21, consistent with previous years, more than three quarters (77%) of people receiving social care support and services in Scotland were aged 65 and older. Furthermore, almost half (463.5 per 1,000 social care clients) of the people receiving social care support were in the ‘elderly and frail’ client group.

Older adults are also much more likely to receive social care support in residential and nursing homes than younger adults. The majority (90.8%) of long stay care home residents are aged 65 and over, with more than half of this group aged 85 and over.

Older people are more likely to be worried about their health and the risks of contracting COVID-19, and are also more likely to experience loneliness and digital exclusion. YouGov polling[5] on behalf of the Scottish Government in June 2022 showed differing levels of concern about coronavirus between age groups, with 28% of those aged 18–24 agreeing with the statement ‘I feel worried about the coronavirus situation’ compared with 44% of those aged 75+. Similarly, one third of those aged 18–24 were worried about the number of COVID-19 cases in Scotland, while over half (52%) of those aged 75+ were worried.

It is well recognised that older people, people who have long term health conditions or who find mobility challenging and who are more likely to use or reside in social care services, may be particularly vulnerable to COVID-19 and more likely to have complex co-morbidities which place them at greater risk of complications if they contract COVID-19.

Source: Scottish Health Survey – telephone survey – August/September 2020: main report

As of 6 October 2020, Scotland’s population was at 5.46 million.

In terms of Social Care, an estimated 1 in 25 people in Scotland were reported as receiving social care support and services at some point during 2020/21. In 2020/21 the rate per 1,000 population of people receiving social care support through any self-directed supported option was 19.4 people per 1,000 population. An estimated 68,000 people in Scotland received home care for the quarter ending 31 March 2021. This is equivalent to 12 people per 1,000 population. Some 44,000 people received funding towards a long stay care home place in Scotland during 2020/21. In addition, a further 6,300 people were supported during a short stay in a care home, such as for respite or for reablement during this time. In 2020/21, an estimated 130,000 people had an active community alarm and/or a telecare service.

As at 31 March 2022 there were 33,352 adults resident in Care Homes and their ages were as follows:

Category (years) - 2022

Mean Age - 81

Mean Age At Admission - 79

Mean Age At Discharge - 85

Median Age - 84

Median Age At Admission - 82

Median Age At Discharge - 87

Care home census for adults in Scotland

Vaccine rates

Vaccine uptake amongst older people including care home residents has been consistently high. The 2023 Spring booster programme saw over 82% of those aged 75 and over and 90.6% of older adult care home residents receive a fourth dose of the COVID-19 vaccine up to July 2023[6].

Staff in Social Care

As at 31 March 2023, there were 208,360 people employed in Social Care in Scotland, The WTE measure of the workforce is 159,150.

Median age of the Social Care workforce is 43. To put this into context, the median age for the total Scottish population aged 16 and over is 49 years and the median age for those between 16 and 65 years old (the traditional working age population) in Scotland is 41 years. For this reason, the sector’s workforce is on average slightly older than would be expected given the age profile of Scotland’s working age population.

Differential Impacts

The impacts of the removal of this temporary policy (the removal of the line of guidance “Staff, visitors and those receiving care and support may choose to wear a mask and this should be supported”) on those in the Age protected characteristic group are as follows:

Positive:

- Any blanket or routine use of face masks in social care settings as a result of misinterpretations of this guidance will stop. This will have a positive impact on communication and on building and maintaining relationships.

- Any inappropriate wearing of face masks as a result of misinterpretations of this guidance will stop. This will have a positive impact as the IPC guidance relating to donning/doffing face masks is more likely to be more accurately followed.

Neutral:

- Will have a neutral effect on concern about coronavirus as some may be more concerned about contracting COVID-19 if there is less mask wearing while others will be reassured that there is less risk if mask wearing is less visible.

- Although social care users are more likely to be older and therefore at greater risk of complications if they contract COVID-19, it is considered that the blanket, routine or inappropriate wearing of face masks that the removal of this guidance will stop is not likely to have a significant effect. This is because face masks will still be worn when appropriate in a risk-based person-centred way, for example, if an individual has a known or suspected infection spread by the airborne or droplet route, and because of high vaccination rates amongst the care home resident population and availability of COVID-19 treatments.

- Additionally, staff, visitors and those receiving care and support in adult social care settings always had (and continue to have) the right to choose to wear a mask. The removal of this line of guidance would not remove that right.

Disability

Background

Disabled people are more likely to experience ill health from contracting COVID-19 than the general population, due to pre-existing health conditions and poorer overall health. Many disabled adults have a range of long-term physical health conditions, such as those affecting the heart and respiratory system, with some people being immunocompromised. These can be linked to increased vulnerability to COVID-19[7]. Of the 14,106 people whose deaths were recorded as involving COVID-19 between March 2020 and March 2022, 93% had at least one pre-existing condition[8].

However, the COVID-19 Highest Risk List ended on 31 May 2022 and this was because of the success of the vaccination programme, and the availability of new medicines to treat COVID-19 meant that the majority of people on the list were at no greater risk from COVID-19 than the general population.

In addition, some groups of disabled people, including those who are deaf and those who live with cognitive difficulties are adversely affected by the inappropriate wearing of face masks. Face mask use can lead to other harms such as communication issues, negatively impact the health and mental wellbeing of individuals and create challenges in building and maintaining meaningful relationships.

Evidence / data

Service users in Social Care

According to the 2021 Scottish Health Survey[9], a third (34%) of adults in Scotland reported living with a long-term condition that limited their day-to-day activities. For people aged 75 and over, 60% had a limiting long-term condition. 1 in 5 Scots identify as disabled, and more than a quarter of working age people have an acquired impairment.

People with learning/intellectual disabilities are also at higher risk of severe COVID-19. The Scottish Learning Disabilities Observatory produced research looking at COVID-19 infection and severe outcomes for people with learning (intellectual) disabilities in Scotland[10]. They found that throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, data indicated that people with learning disabilities were more likely to contract COVID-19, have a more severe case of COVID-19, and were at least three times more likely than people without learning disabilities to die from COVID-19.

People living in care homes are more likely than the rest of the population to have a disability / and or condition as shown in the care home census

Health Characteristic - 2022

Acquired Brain Injury - 758

Alcohol Related Problems - 1305

Dementia - Medically Diagnosed - 17014

Dementia - Not Medically Diagnosed - 1493

Drug-Related Problems - 110

Hearing Impairment - 2161

Learning Disabilities - 2029

Mental Health Problems - 2780

Neurological Conditions - 2003

Other Physical Disability or Chronic Illness - 10341

Requiring Nursing Care - 20233

Visual Impairment - 3379

None of These - 1948

Source: Care home census for adults in Scotland

Staff Social Care

As per the Scottish Social Services Council (SSSC) when asked “Do you consider yourself to be disabled within the definition of the Equality Act 2010?”, of the social care workforce data 2021, 81% reported a disability, 2% reported no and 17% was unknown.

The data on whether workers regard themselves as having a disability is difficult to interpret due to a large proportion of unknown responses.

Source: SSSC: Workforce data 2021

Differential Impact

The impacts of the removal of this temporary policy (the removal of the line of guidance “Staff, visitors and those receiving care and support may choose to wear a mask and this should be supported”) on those in the Disability protected characteristic group are as follows:

Positive:

- Any blanket or routine use of face masks in social care settings as a result of misinterpretations of this guidance will stop. This will have a positive impact on communication and on building and maintaining relationships.

- Any inappropriate wearing of face masks as a result of misinterpretations of this guidance will stop. This will have a positive impact as the IPC guidance relating to donning/doffing face masks is more likely to be more accurately followed.

Neutral:

- Will have a neutral effect on concern about coronavirus as some may be more concerned about contracting COVID-19 if there is less mask wearing while others will be reassured that there is less risk if mask wearing is less visible.

- Although social care users are more likely to have a disability and therefore be at greater risk of complications if they contract COVID-19, it is considered that the blanket, routine or inappropriate wearing of face masks that the removal of this guidance will stop is not likely to have a significant effect. This is because face masks will still be worn when appropriate in a risk-based person-centred way, for example, if an individual has a known or suspected infection spread by the airborne or droplet route, and because of high vaccination rates amongst the care home resident population and availability of COVID-19 treatments.

- Some disabled people (for example those who are immunosuppressed) may consider themselves more at risk of COVID-19 as a result of the removal of this temporary policy although that has to be considered alongside the positive effect on other groups of disabled people, for example those who are deaf or who live with a cognitive impairment, who would be positively affected by a decrease in the inappropriate use of face masks.

- Additionally, staff, visitors and those receiving care and support in adult social care settings always had (and continue to have) the right to choose to wear a mask. The removal of this line of guidance would not remove that right.

Sex

Background

Evidence from the ONS[11] shows that men are at greater risk of becoming seriously ill or dying from COVID-19 than women, however women's overall wellbeing has been more negatively affected.

Men are more likely than women to have certain underlying health conditions which increase clinical vulnerability to COVID-19, including cardiovascular disease, diabetes and ischaemic heart disease[12]. In line with expert advice provided by the JCVI[13], the COVID-19 vaccination programme has been offering primary course and booster vaccinations to protect those at higher risk of severe COVID-19. Additionally, COVID-19 treatments are available for specific groups of people with coronavirus who are thought to be at greater clinical risk. As at July 2023 NHS Scotland may offer additional doses of the coronavirus vaccine to those at higher risk of coronavirus later this year, in line with JCVI advice.

Staff in Social Care

Women are disproportionately represented in health and social care occupations[14], with increased risk of exposure to COVID-19. Risk of exposure to COVID-19 in health and social settings is mitigated by the fact that testing will still take place as clinically required, alongside other infection prevention and control measures. Additionally, health and social care workers have been eligible for COVID-19 vaccination as advised by the JCVI[15].

Evidence/data

Service users in social care

The health and care cross-sectional survey 2022 reports that social care users are more likely to be female (57%) than male (43%).

Social care staff

Within social care, the workforce has a very high proportion of female staff with only around one in six being male: 83% females, 15% males, 2% unknown. There are some areas where men have a higher representation, namely criminal justice (fieldwork services for offenders and offender accommodation services) and residential children’s services (residential child care and school care accommodation), where they can make up around one third or more of people working in those sub-sectors. Non-residential children’s services (adoption services, child care agencies, childminders, day care of children and fostering services) have the highest proportion of female workers at 88% or higher.

Source: SSSC: Workforce data 2021

Differential Impacts

There are no impacts of the removal of this temporary policy (the removal of the line of guidance “Staff, visitors and those receiving care and support may choose to wear a mask and this should be supported”) on those in the Sex protected characteristic group noted.

Pregnancy And Maternity

Background

Pregnant women are at increased risk of severe illness from COVID-19 compared with non-pregnant women[16]. In December 2021 the JCVI added pregnant women to the list of groups considered clinically vulnerable to COVID-19 disease, and hence prioritised for vaccination. In response to this, the Chief Medical Officer for Scotland asked NHS Boards to consider ways to further increase provision of vaccination for pregnant women, for example by establishing dedicated antenatal vaccination clinics. In line with expert advice provided by the JCVI[17], the COVID-19 vaccination programme has continued to offer primary course and booster vaccinations to those at higher risk of severe COVID-19, including pregnant women. As at July 2023 NHS Scotland may offer additional doses of the coronavirus vaccine to those at higher risk of coronavirus later this year, in line with Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation (JCVI) advice.

Live births per 1,000 women, by age of mother, in Scotland in 2019 is as follows:

Age 15-29: 43.4

Age 30-39: 71.0

Age 40-44: 12.8

Source: Data Tables | National Records of Scotland

Evidence/ Data

Service users in social care

We found no information available

Staff in social care

We found no information available

Differential Impacts

There are no impacts of the removal of this temporary policy (the removal of the line of guidance “Staff, visitors and those receiving care and support may choose to wear a mask and this should be supported”) on those in the Pregnancy and Maternity protected characteristic group noted.

Gender Reassignment

Background

Research by the LGBT Foundation on the impact of COVID-19 on LGBT people in the UK found a range of impacts outlined in the section on Sexual Orientation below, also including disruption to trans and non-binary specific healthcare[18].

Evidence/Data

We found no data available for social care workforce or service users

Differential Impacts

There are no impacts of the removal of this temporary policy (the removal of the line of guidance “Staff, visitors and those receiving care and support may choose to wear a mask and this should be supported”) on those in the Gender Reassignment protected characteristic group noted.

Sexual Orientation

Background

Research conducted early in the pandemic by the LGBT Foundation examined the impact of COVID-19 on LGBT people across the UK[19]. Key issues identified included mental health; isolation; substance misuse; eating disorders; living in unsafe environments; financial impact; homelessness; access to healthcare; and access to support. The removal of pandemic restrictions and the return to a more normal way of life, with reduced isolation and improved social connections and access to services, may have positive impacts for LGBT people.

2% of the Scottish population identified as LGBT in 2017 (see Sexual orientation in Scotland 2017).

Evidence/ Data

We found no data available for social care workforce or service users

Differential Impacts

There are no impacts of the removal of this temporary policy (the removal of the line of guidance “Staff, visitors and those receiving care and support may choose to wear a mask and this should be supported”) on those in the Sexual Orientation protected characteristic group noted.

Race

Background

NRS analysis of population data suggests that Scotland is becoming more ethnically and religiously diverse. There is very limited national data on ethnic group for people who access social care. The majority of people receiving social care support are White; in 2020/21, 72% of people receiving social care support were White, a similar proportion to previous years, but ethnicity was recorded as not known or not provided for a further 26%.

Scottish data have shown an increased risk of serious illness and death from COVID-19 among many minority ethnic groups. This mirrors similar trends seen in other countries of the UK[20].

A report by the UK Cabinet Office’s Race Disparity Unit (RDU), drawing on evidence from the Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies ethnicity subgroup, found that a range of socioeconomic and geographical factors, coupled with pre-existing health conditions, contributed to the higher infection and mortality rates for minority ethnic groups[21]. The RDU reported that the main factors behind the higher risk of COVID-19 infection for minority ethnic groups included occupation (particularly for those in frontline roles, such as NHS workers), living with children in multigenerational households, and living in densely populated urban areas with poor air quality and higher levels of deprivation. Once a person was infected, factors such as older age, male sex, having a disability or a pre-existing health condition (such as diabetes) were likely to increase the risk of dying from COVID-19.

The risk of severe COVID-19 is higher for people with certain underlying health conditions. Prevalence of some of these health conditions (including diabetes, coronary heart disease and cardiovascular disease) is known to be higher in certain minority ethnic groups[22]. Vaccination is the best way to protect against the known risks of COVID-19 for those with pre-existing conditions. However, although there has been a high uptake of COVID-19 vaccinations in Scotland overall, uptake levels have not been equal across all population groups. Uptake has been lower in most minority ethnic groups, with Polish, Gypsy/Traveller and African groups having particularly low levels of uptake[23]. This could increase inequality in vulnerability to COVID-19.

Minority ethnic individuals are over-represented in jobs with increased exposure risks to COVID-19, including social care and other key worker roles[24]. Risk of exposure to COVID-19 in social care settings is mitigated by the fact that testing will still take place as clinically required, alongside other infection prevention and control measures. Additionally, health and social care workers have been eligible for COVID-19 vaccination as advised by the JCVI[25].

- Census 2011: Key results on Population, Ethnicity, Identity, Language, Religion, Health, Housing and Accommodation in Scotland – Release 2A | National Records of Scotland (nrscotland.gov.uk)

- Public Health Scotland: People supported – insights in social care: statistics for Scotland

- My Support My Choice: People’s Experiences of Self-directed Support and Social Care in Scotland

- Health and Care Experience Survey - gov.scot (www.gov.scot)

Evidence/ Data

Staff in social care

We found no data available for social care workforce

Service users

The health and care cross-sectional survey 2022 indicates that 96% of service users in social care identify as White, 3% as Asian, Asian Scottish or Asian British, 1% African and 1% Mixed or multiple ethnic groups.

National Records of Scotland analysis of population data suggests that “Scotland is becoming more ethnically and religiously diverse, with an increasing number of people who live in Scotland being born outside of the UK”. This greater diversity among the Scottish population will be reflected in health, social care and prison populations. The data draws from the 2011 Census.

Differential Impacts

There are no impacts of the removal of this temporary policy (the removal of the line of guidance “Staff, visitors and those receiving care and support may choose to wear a mask and this should be supported”) on those in the Race protected characteristic group noted.

Socio-economic disadvantage

Background

Throughout the pandemic people on lower incomes or insecure work, without the protections provided by contractual or statutory sick pay, have been impacted. There are also intersectional considerations, such as the increased risk Black, South Asian or disabled people face with regard to being on lower than average incomes.

Social care staff are generally on lower incomes and taking sick leave due to COVID-19 may mean that staff are only paid statutory sick pay. During the pandemic Scottish Government top-up funding (Social Care Staff Support Fund) ensured staff who needed to isolate were paid the real living wage while off sick due to COVID-19. The fund ended on 31 March 2023.

Evidence / Data

Social care staff

Social care staff tend to earn have lower wages than other healthcare professions, although Scottish Government funding ensures that staff are paid the real living wage.

Differential Impacts

There are no impacts of the removal of this temporary policy (the removal of the line of guidance “Staff, visitors and those receiving care and support may choose to wear a mask and this should be supported”) on those in the Socioeconomic Disadvantage protected characteristic group noted.

Religion Or Belief

Background

Analysis of data from England and Wales by the ONS[26] indicated that risk of death involving COVID-19 early in the pandemic varied across religious groups, with those identifying as Muslims, Jewish, Hindu and Sikh showing a higher rate of death than other groups. However, for the most part the elevated risk of certain religious groups was explained by geographical, socio-economic and demographic factors and increased risks associated with ethnicity.

Evidence/ Data

Service users in Social Care

Population wide data from census shows that 7% of people did not state their religion and 36.7% of people (1,941,116) said they had no religion.

Church of Scotland, 1,717,871, Roman Catholic, 841,053, Other Christian, 291,275, Muslim, 76,737, Hindu, 16,379, Buddhist, 12,795 Sikh, 9,055 Jewish, 5,997 and other religion was 15,196

Source: Religion | Scotland's Census

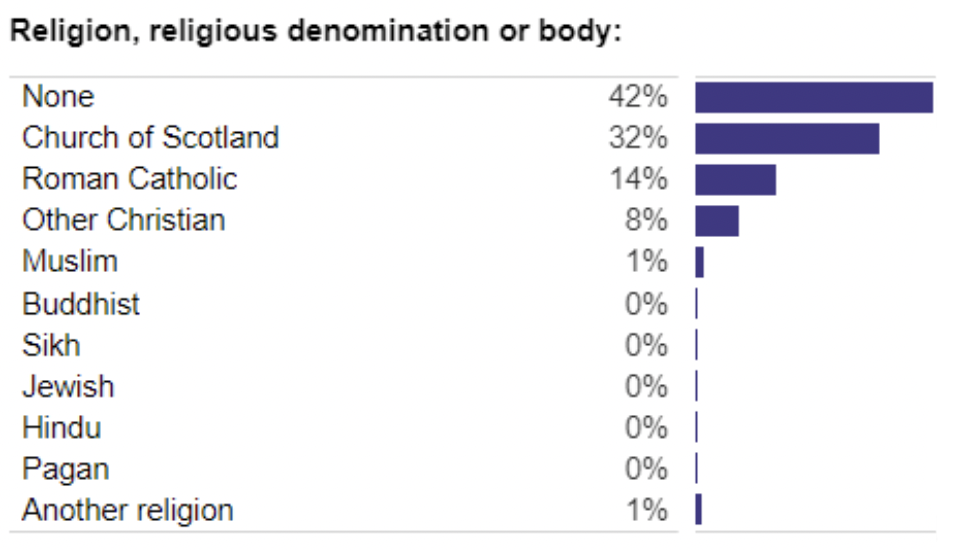

Health and Social Care Workforce

| What religion, religious denomination or body do you belong to? | 2021 | 2022 | Movement 2021- 2022 (Percentage points) |

|---|---|---|---|

| None | 50% | 52% | +2 |

| Church of Scotland | 21% | 20% | -1 |

| Roman Catholic | 14% | 14% | 0 |

| Other Christian | 4% | 4% | 0 |

| Muslim | 1% | 1% | 0 |

| Hindu | <1% | <1% | 0 |

| Buddhist | <1% | <1% | 0 |

| Sikh | <1% | <1% | 0 |

| Jewish | <1% | <1% | 0 |

| Pagan | <1% | <1% | 0 |

| Another religion or body | 1% | 1% | 0 |

| No Answer Given | 7% | 7% | 0 |

Differential Impacts

There are no impacts of the removal of this temporary policy (the removal of the line of guidance “Staff, visitors and those receiving care and support may choose to wear a mask and this should be supported”) on those in the Religion or Belief protected characteristic group noted.

Marriage And Civil Partnership

(the Scottish Government does not require assessment against this protected characteristic unless the policy or practice relates to work, for example HR policies and practices - refer to Definitions of Protected Characteristics document for details)

Background

The numbers of marriages and civil partnerships in Scotland in 2019 are as follows:

Number of marriages: 26,007

Partnerships: 83

Male partnerships: 50

Female partnership: 33

Source: Data Tables | National Records of Scotland

Evidence / data

No data available for social care workforce or service users

Differential Impacts

There are no impacts of the removal of this temporary policy (the removal of the line of guidance “Staff, visitors and those receiving care and support may choose to wear a mask and this should be supported”) on those in the Marriage and Civil Partnership protected characteristic group noted.

Contact

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback