Working with children and young people who have displayed harmful sexual behaviour: evidence based guidance for professionals working with children and young people

Guidance to support professionals who work with children and young people to identify, prevent and mitigate harm caused by children and young people who display harmful sexual behaviour

The continuum of sexual behaviour in childhood

Children and young people’s sexual behaviours range significantly in terms of their nature, frequency, context, and impacts. Not all sexual behaviour displayed by children and young people is normal. However, distinguishing between appropriate non-abusive behaviour and inappropriate or abusive behaviour can be a complex task that requires practitioners to have an understanding of what is healthy and what is abusive or coercive.

As a general guide, if any of the following criteria are met, this may indicate that the child’s sexual behaviour may fall outside of the normative or healthy range and such behaviour may require more detailed assessment:

- occurs at a frequency greater than would be developmentally expected;

- interferes with the child’s development;

- occurs with coercion, intimidation or force;

- is associated with emotional distress by either the child or any other children involved;

- occurs between children of divergent ages or developmental abilities;

- repeatedly recurs in secrecy after intervention by caregivers (Chaffin, et al. 2002).

Additionally, it is helpful to see children’s sexual behaviours on a broad continuum that ranges on the one hand from normal and developmentally appropriate to highly abnormal and violent on the other, as depicted in the NSPCC Responding to children who display sexualised behaviour guide, or below:

Normal

- Developmentally expected

- Socially acceptable

- Consensual, mutual, reciprocal

- Shared decision making

Inappropriate

- Single instances of inappropriate sexual behaviour

- Socially acceptable behaviour within peer group

- Context for behaviour may be inappropriate

- Generally consensual and reciprocal

Problematic

- Problematic and concerning behaviours

- Developmentally unusual

- and socially unexpected

- No overt elements of victimisation

- Consent issues may be unclear

- May lack reciprocity or equal power

- May include levels of compulsivity

Abusive

- Victimising intent or outcome

- Includes misuse of power

- Coercion and force to ensure victim compliance

- Intrusive

- Informed consent lacking, or not able to be freely given by victim

- May include elements of expressive violence

Violent

- Physically violent sexual abuse

- Highly intrusive

- Instrumental violence which is physiologically and/ or sexually arousing to the perpetrator

- Sadism

Hackett (2010)

Hackett’s continuum model is not meant to imply fixed or rigid categories of behaviour, but a spectrum where children’s behaviours may be more or less problematic or harmful depending on a range of contextual factors. Therefore, classifying the behaviour is not always exact – there may be behaviours that sit on the cusp of categories. A child’s behaviour can also escalate over time from one category to the next (e.g. inappropriate behaviour that is regularly repeated would become problematic in nature). However, it is often the case that de-escalation occurs as the child increases maturity and understanding of their own behaviour and its impact on those around them.

Some behaviours may be problematic for adults but may not be considered problematic by the child or young person. In such situations the following might be useful questions for the professional to ask:

Does the behaviour

- put the individual or others at risk of physical harm, disease or exploitation?

- interfere with the individual’s overall development, learning, or social and family relationships, or that of others?

- cause the individual, or others, feelings of discomfort, confusion, embarrassment, guilt or to feel negative about themselves?

- result in dysfunction for the development of healthy relationships or is it destructive to the family, peer group, community or society? (Chaffin, et al., 2002)

Harmful sexual behaviours vary in nature, degree of force, motivation, context, level of intent, level of sexual motivation, and the age and gender of victims. Care should be taken in evaluating sexual motivation. Sexualised language, for instance, is rarely sexually motivated and would typically not be an example of inappropriate or problematic sexual behaviour unless the language is deliberately used to sexualise or degrade others.

Just as there is a continuum of behaviour, there needs to be a continuum of potential responses, ranging from broad educational input on consent and relationships, through to multi-agency public protection arrangements to manage those who commit serious sexual offences and who present a risk of harm to themself or others.

Whether an immediate response to harmful sexual behaviour is required depends on interacting considerations relating to risk, impact, age and context. In all actions and decisions, the primary professional consideration must be to safeguard and promote the wellbeing of all children involved.

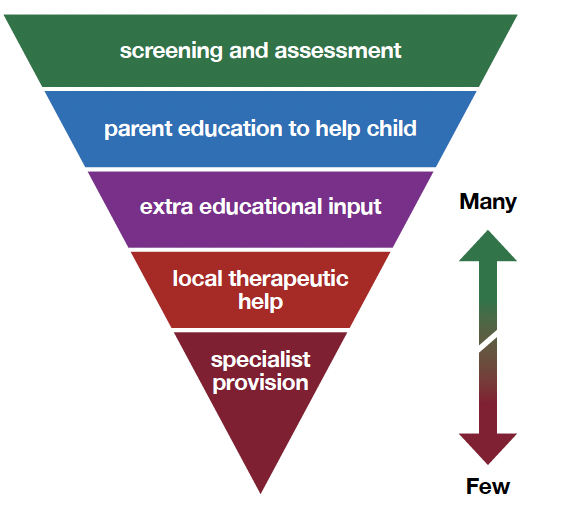

In addition to the initial response and support offered to low level cases in frontline settings, several levels of service response and intensity are required in order to address various levels of need and concern, as highlighted in the following model (Morrison, 2004).

In all cases where a child or young person displays sexual behaviour that may cause significant harm, immediate consideration should be given as to whether action should be taken under child protection procedures, in order both to protect children harmed or at risk of harm and to address any child protection concerns that may - at least, in part - explain why the child or young person has behaved in such a way.

Contact

Email: child_protection@gov.scot

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback