Construction Procurement Handbook

Guidance for public sector contracting authorities on the procurement of construction works.

Chapter 5 Contract Selection and Procurement Strategy

2. Summary of Generic Procurement Strategies

3. Common Procurement Strategies and their Characteristics

4. Early Integrated team/Partnering

6. Traditional Lump Sum Strategy

8. Design Develop and Construct

11. Revenue Financed

12. Variant: Two Stage Tendering

13. Variant: Target Cost Contracts

15. Selecting a Procurement Strategy and Form of Contract

16. Short List Procurement Strategies Based on Pass/Fail Criteria

17. Example One

18. Example Two

19. Select from Short List Based on a Weighted Scoring of Characteristics

20. Introduction to Risk Management and Apportionment

22. Risk Management

23. Amendments to Standard Form Contracts

24. Selecting a Form of Contract

25. Standard Form Construction Contracts

26. Other Contracts

29. Choosing from the Different Forms of Contract

30. Management of the Contract

35. Other Useful Sources of Advice and Guidance

Introduction

1.1 The Review of Scottish Public Sector Procurement in Construction noted that a wide range of contract forms were being used by public sector clients for the procurement of construction works. In some cases, a clear selection process had been applied to the choice of contract which was appropriate for the nature of the work, the procurement method and the risks lying within the project. However, in other cases, it appeared that much less thought or planning had been given to the form of contract used where there was a reliance on historic practice regardless of whether the contract type was the best fit or approach for the project in question.

1.2 This Chapter of the Construction Procurement Handbook provides an overview on the relative merits of a range of procurement strategies and forms of contract. This will help to inform a contracting authority’s decision on the procurement strategy and form of contract it wishes to adopt for the delivery of its desired project outcomes.

Summary of Generic Procurement Strategies

2.1 There are five generic procurement strategies:

- Integrated

- Traditional

- Design and Build

- Management

- Revenue Financed

2.2 Each has variants, and further options can be applied to some of the variants:

- Frameworks

- Two Stage Tenders

- Target Cost Contracts

2.3 In addition, there are a number of forms of construction contract which can be used with each variant and/or option which reflect differences in risk allocation between the contracting parties and differences in the mechanisms for payment, for variations to the contract required by the client and for resolution of disputes.

2.4 The two forms of contract most commonly used for construction works in Scotland are:

- The Joint Contracts Tribunal (JCT) as amended for use in Scotland by the Scottish Building Contract Committee Ltd.; and,

- The New Engineering Contract (NEC).

2.5 Two standard forms of contract which, historically, were widely used (The Institution of Civil Engineers, ICE Contract and the Government Conditions of Contract, GC Works) are no longer maintained by their publishers and were withdrawn from sale in 2011. While some procuring authorities continue to use these on a regular basis, those authorities not familiar with them may wish to consider other, more contemporary forms of contract.

2.6 Other forms of contract such as the FIDIC suite published by the International Federation of Consulting Engineers, and the ICC Conditions of Contract, published by the Association of Consulting Engineers (ACE) and the Civil Engineering Contractors Association (CECA), are available. However, these are not in common use and are not considered in detail in this chapter.

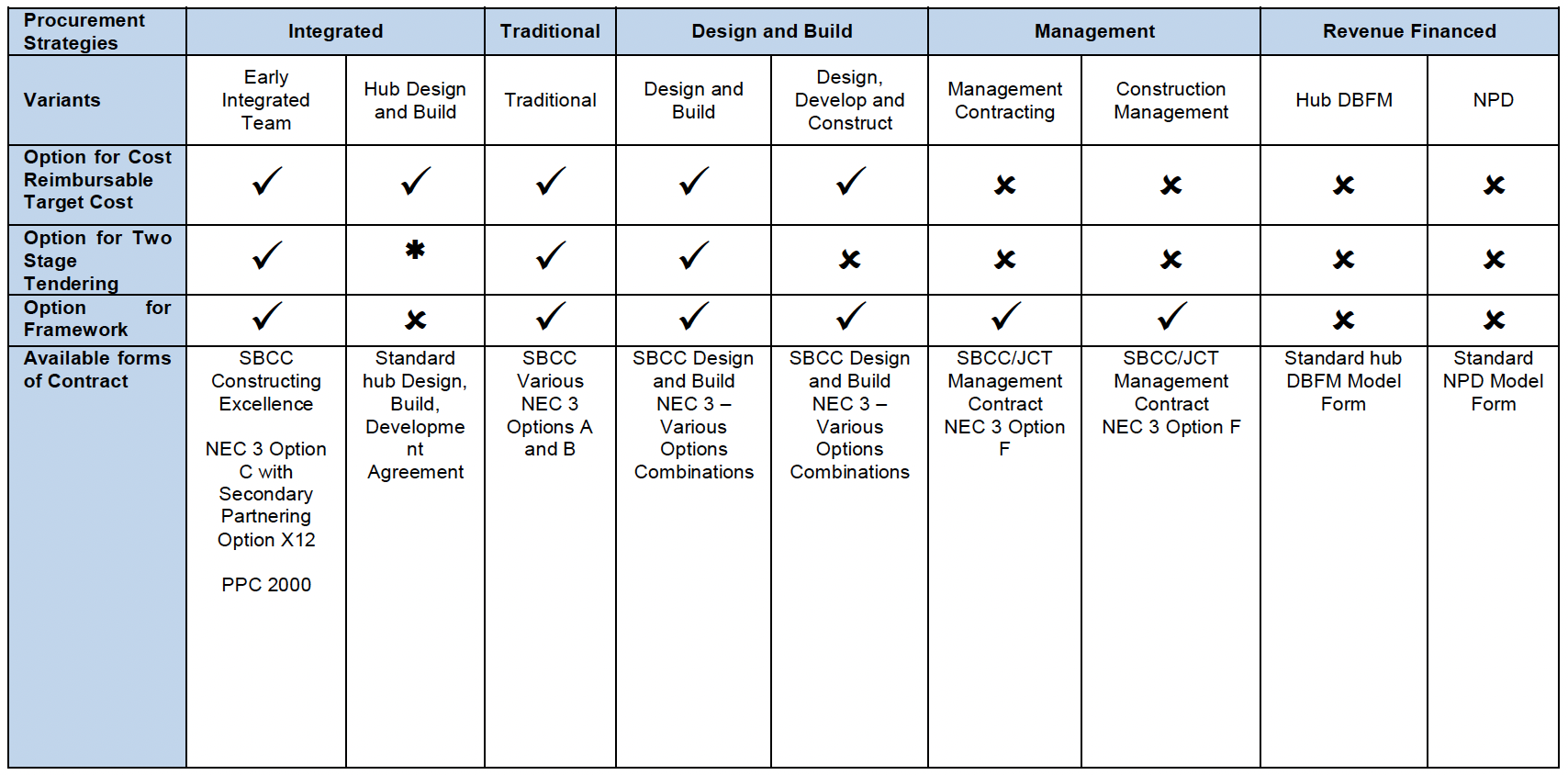

2.7 A summary of the generic procurement strategies and associated forms of contract and their potential applicability is contained in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Summary of Generic Procurement Strategies

Common Procurement Strategies and their Characteristics

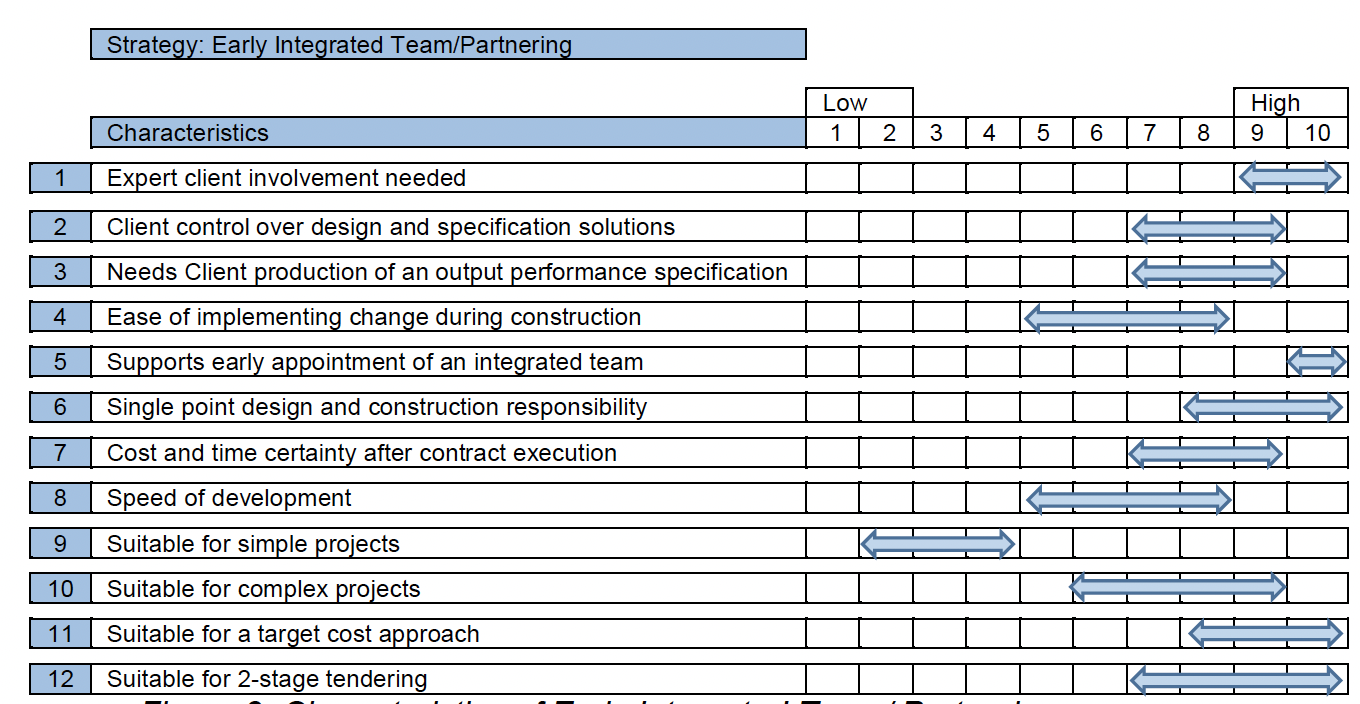

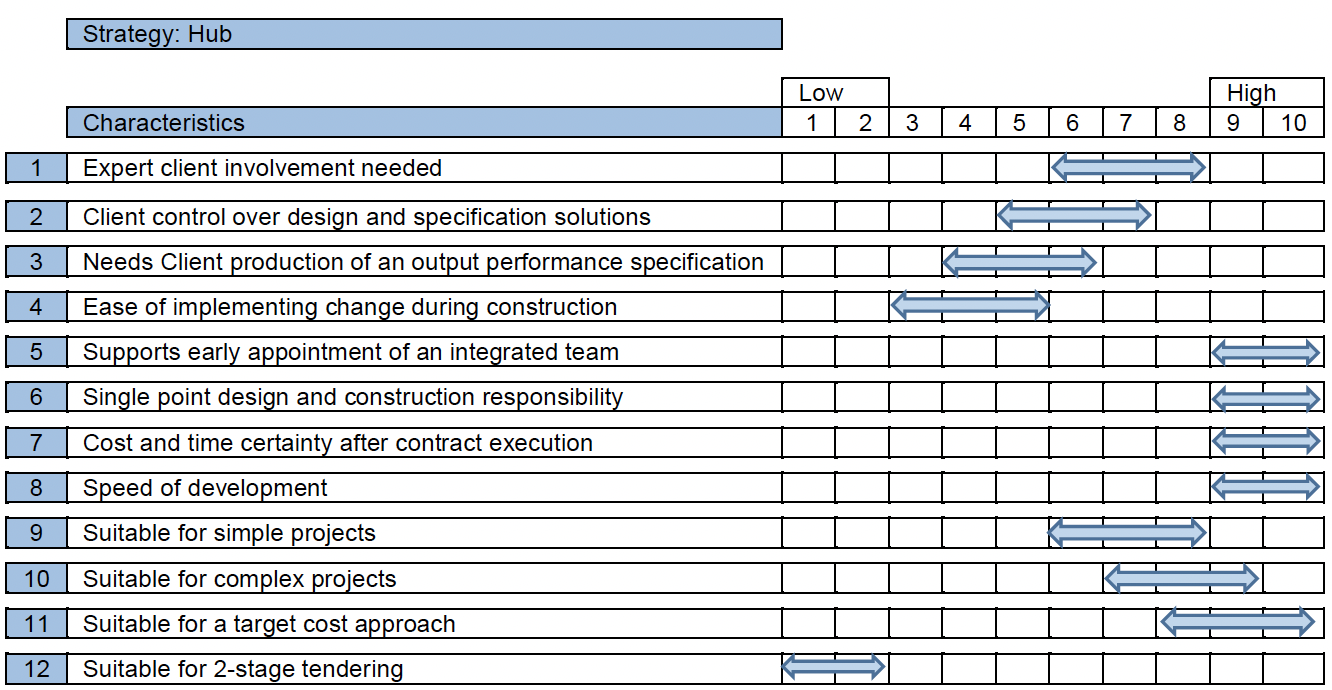

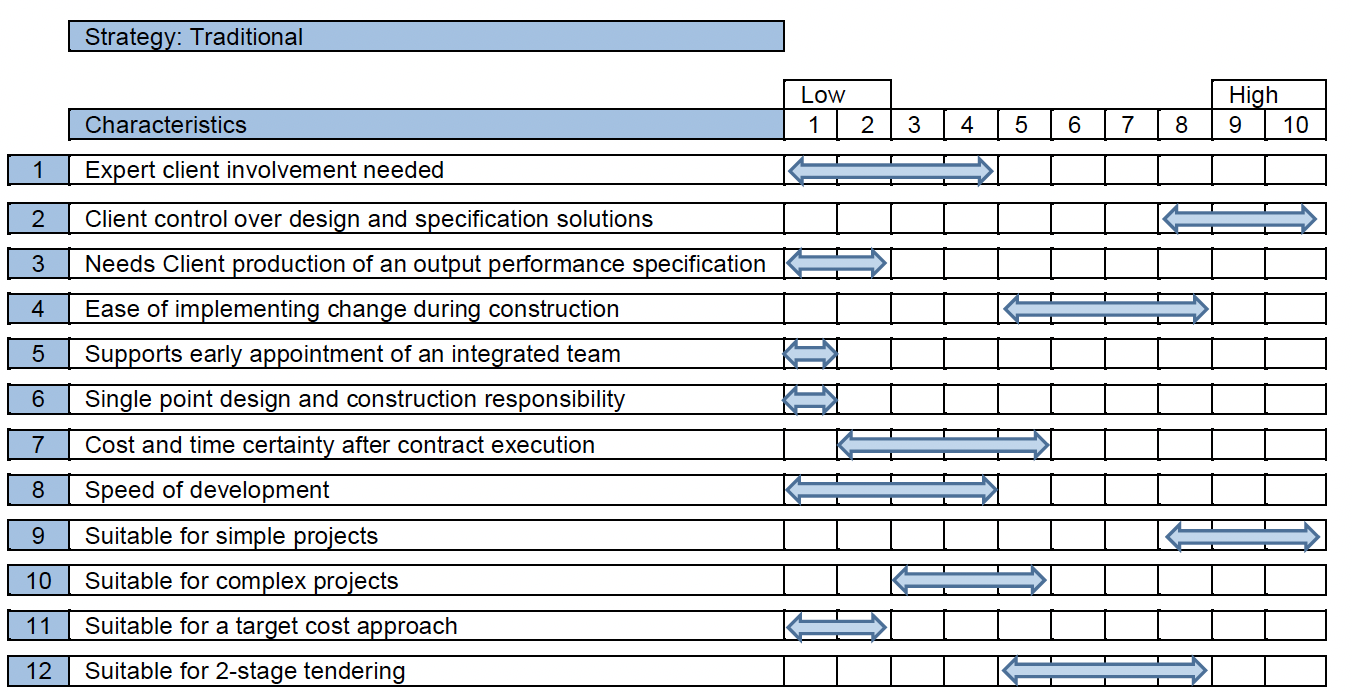

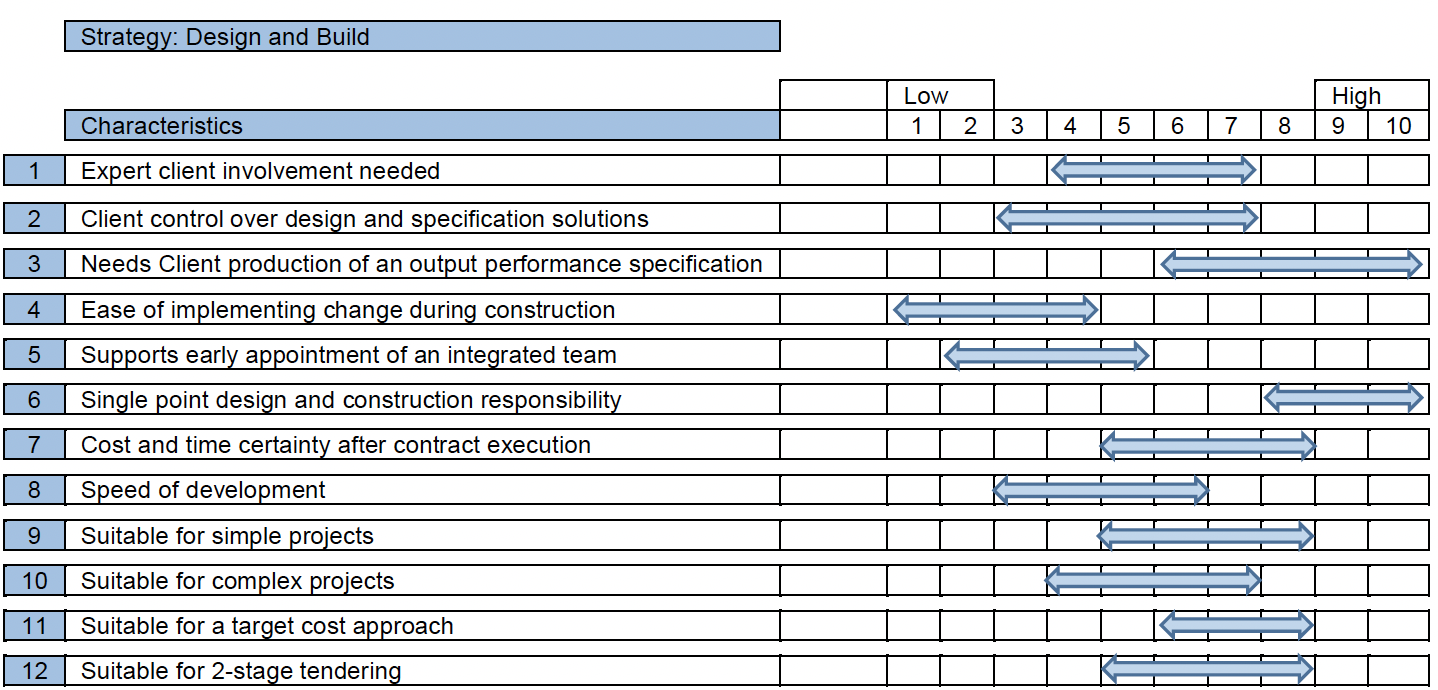

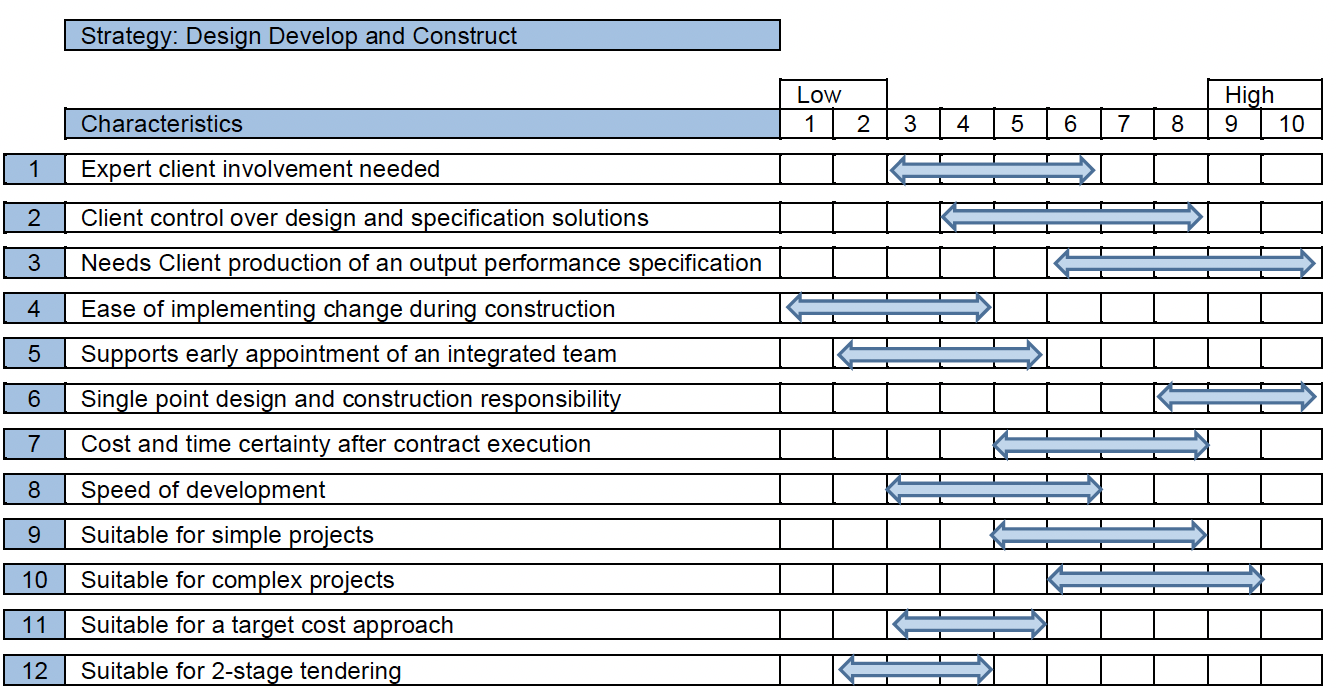

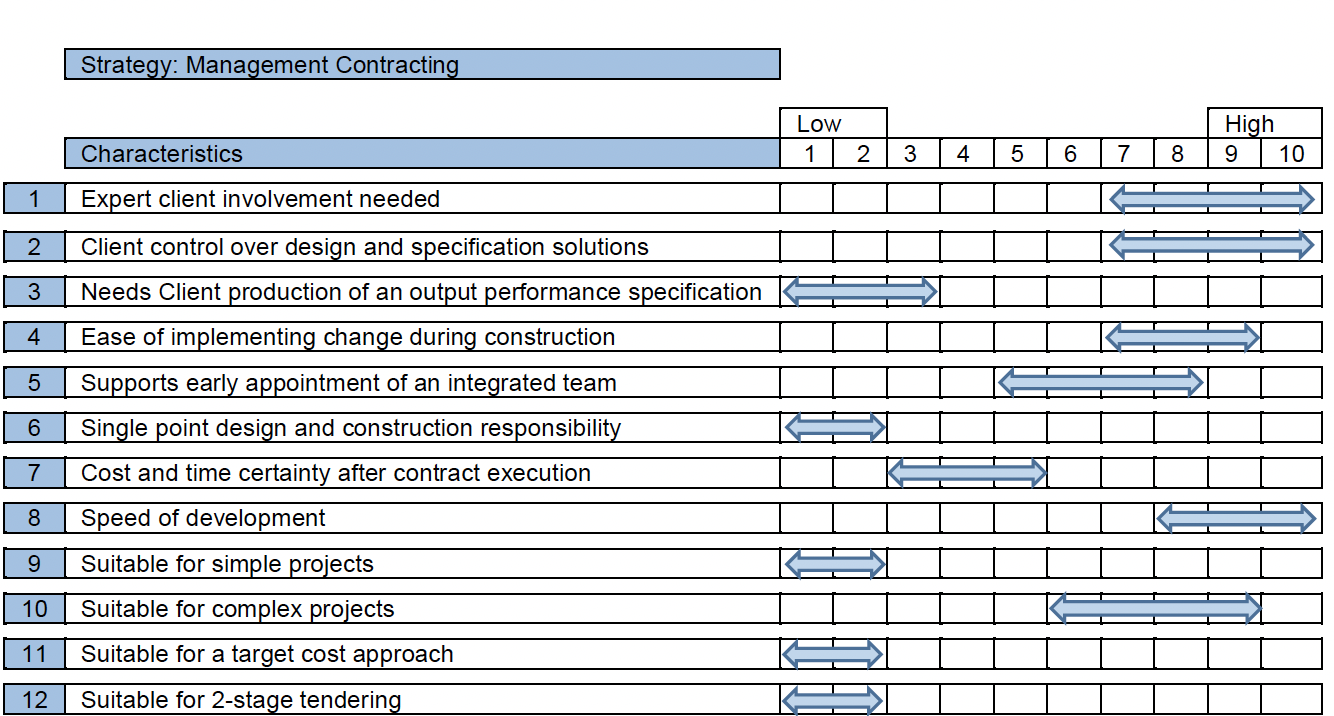

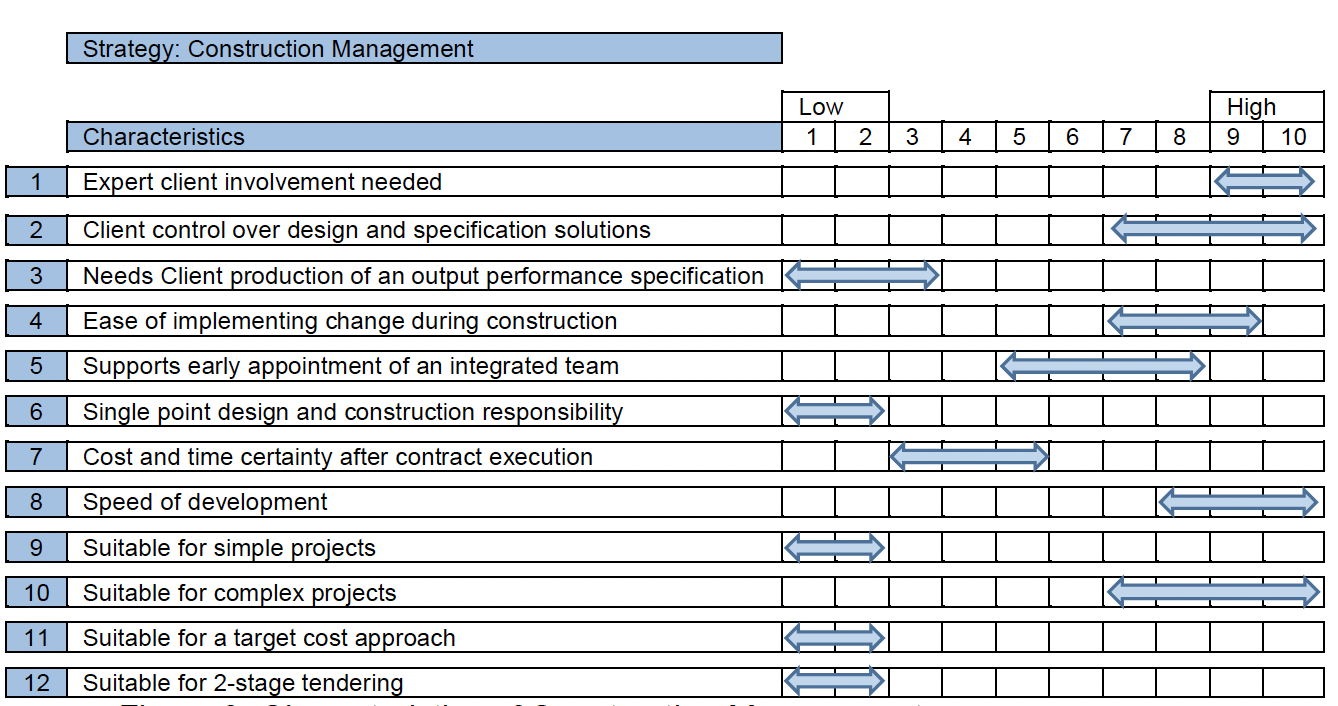

3.1 In this section, the key characteristics of a range of commonly used procurement strategies are described. Each description is accompanied by an assessment, in matrix form, of the relative impact (from low (1) to high (10)) of a set of twelve specific characteristics may have on the particular procurement strategy; for example, what level of client expertise is required in its application or is it suitable for simple or more complex projects. The twelve characteristics are described in Figure 2, along with a description of what each characteristic assesses.

Figure 2: Characteristics of Common Procurement Strategies

Characteristic

Expert client involvement needed

What the Characteristic Assesses

The degree of expertise, low-high, needed by the client body

Characteristic

Client control over design and specification solutions

What the Characteristic Assesses

The amount of control afforded to the client in selecting a design solution, rather than simply testing if the specified project benefits are achieved.

Characteristic

Needs the client to produce an output performance specification. Often called "Employers Requirements" or "Accommodation Requirements"

What the Characteristic Assesses

The extent to which the procurement strategy is reliant on a detailed set of client technical requirements. For each design element this is normally expressed as achieving a minimum performance level.

Characteristic

The ease of implementing change during construction

What the Characteristic Assesses

The ease of instructing a change and of agreeing any implications of cost and time

Characteristic

Supports the early appointment of an integrated team

What the Characteristic Assesses

The extent to which the strategy enables contractors and designers to work collaboratively from an early stage of the project

Characteristic

Single point design and construction responsibility

What the Characteristic Assesses

The extent to which responsibility for both design and construction is contractually combined.

Characteristic

Cost and time certainty after contract execution

What the Characteristic Assesses

Measures the degree to which construction phase risks are typically able to be transferred to the contactor

Characteristic

Speed of development

What the Characteristic Assesses

A measure of the relative speed from project inception to start of construction

Characteristic

Suitable for simple projects

What the Characteristic Assesses

Low resource levels and limited expertise needed - low client administration

Characteristic

Suitable for complex projects

What the Characteristic Assesses

Supports a high level of client involvement, specialist contractor design, optional supply chain intervention by the client, complex risk management

Characteristic

Suitable for a target cost approach

What the Characteristic Assesses

The extent to which the strategy supports the use of a collaborative approach to procure to a cost target

Characteristic

Suitable for 2-stage tendering

What the Characteristic Assesses

The extent to which the strategy supports a 2-stage tendering approach

3.2 Selection of the most appropriate strategy should be undertaken following a project specific analysis of the relative characteristics of each option. As a first step in the selection process, all the procurement strategy options should be sifted by means of simple pass/fail criteria to identify those most suitable for the project in question. The remaining options should then be assessed using a more rigorous weighted score analysis to help inform the choice of the optimum project specific strategy. This process is described in more detail from section 15 onwards.

3.3 The following procurement strategies are considered:

- Early Integrated Team/Partnering

- Scotland’s hub Programme

- Traditional Lump Sum

- Design and Build Strategies

- Management Strategies

Along with the following variants:

- Two Stage Tendering

- Target Cost Contracts

- Frameworks

Early Integrated Team/Partnering

4.1 The benefits of developing projects collaboratively between the various parties to a project is well established – working together as a team, for the mutual benefit for all, minimises wasteful activities. For example, the hub programme (further details below) has been developed in Scotland on these principles. However, it is important to note that the approach does not replace formal contracts of engagement between parties or proper and appropriate management structures and procedures. It is a pragmatic way of working together to find ways of delivering the project to the required quality within budget and within programme. Three forms of standard contract that have been developed to facilitate partnering approaches include:

- JCT Constructing Excellence;

- NEC suite of contracts (e.g. NEC 3 and NEC4 with appropriate collaboration and partnering options); and

- PPC 2000 with PPC(S)2000 (a supplement containing alternative attestation clauses and amendments to PPC2000 in accordance with Scots Law).

4.2 The first two rely on a series of bilateral contracts between the client and each supplier. PPC 2000 provides for a multilateral partnering agreement.

4.3 Although a number of operating models exist for partnering, most embody the following principles:

- The client develops a functional, outcome focussed brief with specific requirements covering budget, sustainability criteria and community benefits;

- An integrated team of designers, contractors (including specialist design contractors if appropriate) and facilities managers is assembled;

- In collaboration with an informed client, the team develop the most appropriate design solution, normally based upon open-book cost management and transparent risk identification, mitigation and allocation;

- The subsequent construction contract can be based on a variety of approaches but will be characterised by fairness in risk allocation and payment mechanisms;

- Key performance measurements are used to drive improvement and include reviews of behaviours as well as hard processes.

Partnering is often used in framework arrangements where the long-term benefits of teams who work together regularly can be realised.

4.4 The potential benefits are;

- Maximises the opportunities for innovation in developing the optimum solution.

- Provides very good risk management.

- Strong alignment with client objectives and outcomes.

- Strong basis to develop continuous improvement in long term relationships.

- Potential to minimise claims during construction because of better risk identification, mitigation and allocation.

4.5 The potential risks include;

- Requires strong client leadership and experience.

- Disputes between partners can be more difficult to resolve using contractual remedies - instead resolution relies on the operation of mutual trust and respect between parties, and escalation if necessary to senior management.

- Care and diligence is needed to understand the final risk allocation and its management in the construction contract.

- Relies on good benchmarking and cost data to establish a cost ceiling in order to demonstrate value for money, especially if competitive tendering is not used for all packages of works.

Figure 3: Characteristics of Early Integrated Team/ Partnering

Scotland’s Hub Programme

5.1 The Scotland-wide hub programme is an integrated procurement strategy based on a partnership between the public and private sectors to deliver new community facilities that are built by five hub companies spread across Scotland. It is designed to provide the public sector with a mechanism to deliver and manage buildings more effectively. The hub companies (hubCos) are jointly owned - 60% by a competitively procured private sector development partner (PSDP) and 40% by the public sector. Each hubCo can undertake project development work, strategic support services (professional consultancy services) or facilities management services. Further details about the hub programme can be obtained from Scottish Futures Trust.

5.2 Public bodies wishing to participate (Participants) with their local hubCo are required to sign a Territory Partnering Agreement (TPA). Having signed a TPA, Participants with a project meeting the original procurement criteria – essentially a project delivering community services – can issue a ‘New Project Request’ (NPR) to the hubCo. This consists of a project brief and an associated budget which, if accepted by the hubCo, means that an Integrated Team, consisting of a Tier 1 contractor, designers and other consultants as appropriate, is then selected from the hubCo supply chain in consultation with the Participant. A proposal for delivering the project, based on a scheme design, is then developed collaboratively over a period of approximately three months.

5.3 Design development is a joint exercise between the Integrated Team and the Participant. Risks are jointly identified, surveys and investigations carried out and options considered. A project development fee is only payable by the Participant if the proposal meets the project brief and budget criteria set out in the NPR (and can also demonstrate value for money). All components of the project development fee are subject to percentage fee caps set at the time of the original, competitive PSDP procurement.

5.4 Once the initial (“Stage 1”) proposal is accepted, the hubCo develops the design and, via its Tier 1 contractor, competitively tenders a minimum of 80% of the prime cost of the project on a transparent open book basis to establish a “Stage 2” proposal. The Tier 1 contractor’s overheads, preliminaries and profit are subject, again, to percentage caps of the prime cost. The “Stage 2” proposal is presented to the Participant and if this is accepted, a development contract is entered in to between the Participant and hubCo.

5.5 A “back-to-back” construction contract (where the contract between the hubCo and the Tier 1 contractor mirrors the obligations of hubCo to the Participant), is let at the same time between the hubCo and its Tier 1 contractor. The standard hub terms are based on those of a design and build contract. Recognising the period during which the Integrated Team has identified, mitigated and priced risks, the terms include for the risks on ground conditions, weather, utilities and contamination (with exceptions for areas not able to be surveyed) to be transferred to the hubCo and in turn to its Tier 1 contractor.

5.6 Each hubCo has an initial 20-year term. The performance of each hubCo is monitored by a Territory Partnering Board, with a representative from each Participant, against both project Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) and continuous improvement KPIs.

5.7 The potential benefits are;

- Significant time and resource is saved by the client not needing to advertise or competitively tender for designers or a main contractor, as these steps have already been undertaken for the appointment of the PSDP.

- Embraces all the benefits of Early Integrated Team working.

- Provides very good risk management.

- Provides benefits of a long-term relationship with the hubCo.

- Provides very good time and cost certainty in the absence of variations.

5.8 The potential risks are;

- Relies on clients being able to identify well defined project outcomes (a Brief) and to have a good understanding of the likely outturn cost.

- Relies on robust interrogation of the hubCo proposals by the client.

- Choice of contractors and consultants are mostly restricted to members of the hubCo supply chain, although there is a requirement for this to be refreshed regularly in accordance with the relevant Territory Partnering Agreement.

Figure 4: Characteristics of Hub

Traditional Lump Sum Strategy

6.1 With this type of contract, the design team are employed directly by the client to fully develop the design prior to going out to tender. Suitable contractors are then invited to submit a tender priced against the client’s requirements. Traditionally, this can comprise a Bill of Quantities. However, it is becoming increasingly common for contracts to be based on drawings and specifications, or activity schedules with contractors needing to satisfy themselves as to the quantities of material required.

6.2 The construction contract is with a main contractor who has responsibility only for the construction works. If the design has been fully thought out, developed and frozen, this type of contract should provide a reasonable degree of cost certainty at tender stage, subject only to client risk events, such as unforeseen ground conditions. However, by their nature, Lump Sum Contracts may be less appropriate where the timescales for delivery of the project may mean that a fully developed design cannot be prepared in advance of tendering; in which case subsequent design development changes will usually lead to cost and, possibly, time escalation. Typically, this procurement strategy also uses forms of contract where the client generally retains the risk of, for example, unexpected ground conditions, adverse weather and utilities. The client should also ensure the project budget includes an appropriate contingency allowance to cover such risks. For example, an allowance of approximately 10% on cost and 10% for extensions of time is typical, but the precise level will depend on the level of complexity and uncertainty of the project

6.3 The potential benefits are:

- Price certainty and transfer of risk to the main contractor is achieved at contract award, provided that no subsequent changes are instructed to the design, and no client held risk events occur.

- A high level of quality in design and construction is achievable as the scope of the work is prescribed on an input specification basis by consultants reporting directly to the client.

- The client retains individual direct contractual relationships with the design team, cost consultant and main contractor.

- Changes to the works can be simply instructed and then evaluated on the basis of known prices obtained in competition without necessarily excessive cost or time implications.

- Tender pricing can be achieved based on a comprehensive bill of quantities which is attractive to the contracting market.

6.4 The potential risks are:

- The overall development programme may be longer due to the need to produce a fully detailed design before the project goes out to competitive tender and work starts on site.

- The Client must have the resources and access to the expertise necessary to administer the contracts of consultants as well as the main contractor.

- The consecutive timing of design and construction results in a lack of continuity between the designer and the builder (and hence little opportunity for input on ‘buildability’).

- Not all project risk is transferred to the contractor and some is retained by the client. Claims for delay and disruption can arise if: the design is not fully detailed prior to agreeing the contract sum; the Client varies the design afterwards; if outstanding design information is late; or the issued design contains errors or omissions.

- Defects; where there is a dispute over whether the cause is design or workmanship, it can prove difficult for the client to identify the party responsible and secure rectification.

Figure 5: Characteristics of a Traditional Strategy

Design and Build

7.1 In a “Design and Build” contract, a single supplier is appointed by the client to undertake both the design and construction of the facility. Typically, the client’s own design team (either in-house or outsourced) develop a concept or scheme design to RIBA Stage 2 along with an output performance specification. Together these form the “Employer’s Requirements” or “Works Information” depending on the form of contract chosen. The client then invites competitive tenders in accordance with the guidance set out and relevant procurement legislation referred to in Chapter 7 of this handbook, covering “Procurement Route 2”.

7.2 The contractor is likely to deliver the greatest performance benefits to the client through innovation and standardisation, where appropriate output specifications are produced by the client. Where an output specification is not sufficiently developed, there is a risk that the quality, design and performance of the completed facility may be compromised by a contractor pursuing the lowest cost material specification or design solution. Careful attention to the output specification is required in order to achieve the required outcome. Often the client retains the services of the original design consultants to scrutinise the contractor’s developing design and to confirm it is compliant with the Employers Requirements.

7.3 There may be some circumstances where it may be beneficial for the design and build procurement option to be extended to cover maintenance and also possibly operation of the facility for a substantial period known as Design, Build, Finance & Maintain (DBFM) or Design, Build, Maintain & Operate (DBMO). By including the maintenance and operation requirements within a design and construction contract, the supplier has an increased opportunity for adopting innovative solutions that provide greater value for money when considering whole life costs.

7.4 The potential benefits are:

- Low tendering and preparation cost to the client.

- Single point responsibility for design and cost risks, including design errors and omissions.

- Statutory Approvals are the responsibility of the contractor

- Potential for more economical construction due to earlier consideration of building methods (‘buildability’).

- Could result in a shorter overall design and construction period.

7.5 The potential risks are:

- The client’s requirements must be properly specified prior to signing the contract as client changes to the scope of the project, once let, can be expensive.

- The client has little control over design once the contract is let, as the building is specified on a performance basis with output specifications.

- Design and build is unsuitable for complex, challenging projects which benefit from a developed design prior to pricing.

Figure 6: Characteristics of Design and Build

Design Develop and Construct

8.1 Just as in a design and build contract, a single supplier is responsible for both the design and construction of the facility. However, in the case of Design Develop and Construct, the client’s own design team (either in-house or outsourced) develop the design to a much greater level of detail than in a simple Design and Build strategy. Typically, this will be to RIBA Stage 3 and will include both fully designed input specifications as well as output specifications for those elements of design being left to the successful contractor to complete. Together these form the “Employers Requirements” or “Works Information” depending on the form of contract chosen. Commonly, Planning Consent is secured by the client in advance of the tender, leaving the contractor to comply with any Planning Conditions and to secure Building Warrants and other statutory approvals. The client then invites competitive tenders in accordance with the guidance set out in Chapter 7 of this handbook, covering “Procurement Route 2”.

8.2 The successful contractor will either employ their own design team or, more commonly, have the client’s team novated to them. The contractor is then required to complete the outstanding design – often integrating many specialist contractor elements such as cladding, steelwork, building services – all of which must comply with the relevant output specifications contained in the Employers Requirements.

8.3 Where an output specification is insufficiently well developed, there is a risk that the quality, design and performance of the completed facility may be compromised by a contractor pursuing the lowest cost material specification or design solution. Careful attention to the output specification elements is required.

8.4 There may be some circumstances where it may be beneficial for the design and build procurement option to be extended to cover maintenance and also possibly operation of the facility for a substantial period. By including the maintenance and operation requirements within a design and construction contract, the supplier has increased opportunity for adopting innovative solutions that provide greater value for money when considering whole life costs.

8.5 The potential benefits are:

- Single point responsibility for design and cost risks, including design errors and omissions.

- Greater control of the design and specification compared to a simple design and build.

- Some, if not all, Statutory Approvals are the responsibility of the contractor.

- Potential for more economical construction due to early consideration of building methods (‘buildability’).

- Could result in a shorter overall design and construction period compared with a traditional strategy.

8.6 The potential risks are:

- The client’s requirements must be properly specified prior to signing the contract as client changes to the scope of the project, once let, can be expensive.

- The client has little control over the outstanding design and quality standards once the contract is let, other than to issue variations to their Employers Requirements.

- Design coordination issues can arise between the Employer Requirements and those elements still to be designed by the contractor.

Figure 7: Characteristics of Design, Develop and Construct

Management Contracting

9.1 This is a ‘fast track’ strategy which overlaps the design and construction stages and enables contracts for early work packages, for example groundworks and steelwork, to be placed before the overall design is complete.

9.2 A management contractor is appointed by the client to manage the overall construction contract in return for a management fee. The design team, however, is not part of the management contractor’s team and are either the client’s own in house design team or appointed separately by the client as appropriate. That said, if appointed before the design is complete, the management contractor, can advise on buildability, programming, sequencing and the procurement of the various works packages.

9.3 The contracts for the various works packages are between the management contractor and the individual trade contractors. Costs are controlled by the development of a cost plan in which estimates of the costs of works packages are initially used for budgeting purposes prior to being replaced with actual costs obtained in open book competitive tenders. The projected final cost (still subject to risk events) will only be known once the final works package has been awarded and hence management of the cost plan focussing on risks and contingencies is extremely important.

9.4 The potential benefits are:

- Early completion is possible due to a shorter overall development period achieved by overlapping design and construction activities, even with complex buildings.

- While the client maintains direct control over the design team, the management and trade contractors can contribute to design development and improve the management and buildability of the construction process.

- Particularly suitable where there is complex design from specialist works package contractors to be incorporated

- The management contractor assumes some risk for the performance of the trade contractors.

- Changes can be accommodated more easily than in other forms of contract in both let and unlet packages provided there is little or no impact on the overall project timetable.

- Achieves good alignment of objectives between client and management contractor.

9.5 The potential risks are:

- The final price and timescale are not fixed at the commencement of the works and do not become so until the last work package has been let, and even then, are subject to the risks that lay with the client under the form of contract chosen.

- If the management contractor fails to organise and coordinate the various works packages it could result in claims from package contractors that the client could become responsible for.

- The client must have the resources and access to the necessary expertise to deal with separate design consultants and the management contractor and the scrutiny of each of the works package tenders.

- Management Contracting is unsuitable for an inexperienced and/or hands-off client as there is a risk of increased costs and delays arising from ineffective administration.

Figure 8: Characteristics of Management Contracting

Construction Management

10.1 This is also a ‘fast track’ strategy where works packages are let before the design of later packages has been completed. A construction manager is appointed by the client to manage the overall contract in return for a management fee and, as with management contracting, the project can benefit from the early involvement of the contractor. The main, and very significant, difference from management contracting is that the contracts for the works packages are placed directly between the client and the trade contractors. As with management contracting the projected final cost (still subject to risk events) will only be known once the final works package has been awarded. Costs are controlled by the development of a cost plan in which estimates of the costs of works packages are initially used for budgeting purposes prior to being replaced with actual costs obtained from open book competitive tenders. The management of the cost plan focussing on risks and contingencies is, therefore, extremely important.

10.2 Construction management was largely devised for use in the commercial development market and, where there are examples of public sector projects being successfully procured via this route, this approach is generally unlikely to represent an appropriate option for public sector procurers other than in exceptional circumstances and where the client has the necessary resources and experience. While the use of construction management is not ruled out entirely, it should only be adopted following full consideration of the risks and benefits and an assessment of the management team’s level of resource and expertise. Finally, in the case of clients subject to the requirements of the Scottish Public Finance Manual, the choice of this route must be approved by the responsible Minister.

10.3 The potential benefits are:

- Construction management should reduce the overall project timescale by allowing procurement and construction to proceed before the design is completed.

- The client controls the design and changes can be accommodated in let and unlet packages provided there is little or no impact on the overall project timetable.

- It can be applied to a complex building and has opportunity to allow good buildability input.

- Achieves good alignment of objectives between client and the construction manager.

- Particularly suitable where there is complex design from specialist works package contractors to be incorporated.

- The client contracts directly with trade contractors, which could result in lower prices and allows poor performance to be dealt with directly.

10.4 The potential risks are:

- The final design, price and timescale are not fixed at the commencement of the works and do not become so until the last work package has been let, and even then, are subject to the risks that lay with the client under the form of contract chosen.

- The client bears most of the total risk including delays, disruption, design and its coordination with construction; there must be a robust process for instructing and approving changes.

- The construction manager commonly does not assume any risk other than negligence, is not contractually responsible for achieving programme and cannot instruct third parties.

- The design team must envisage both the totality and detail of the design at the outset, accommodating uncertainty, procuring long lead-time items early and avoiding retrospective change.

- Clients need to be experienced, informed, decisive, and have the necessary expert resources to administer the contracts of the separate design team members, the construction manager, and many trade contractors.

- Construction management contractors must be sufficiently incentivised to avoid fee escalation; they should be experienced in construction management and have very good leadership skills.

- The client must place an even greater premium on risk management in construction management than under other procurement strategies and needs to ensure that roles and responsibilities are well defined at the outset.

- The construction manager can build better team relationships with trade contractors and hence potentially resolve disputes swiftly in the absence of a direct commercial relationship.

Figure 9: Characteristics of Construction Management

Revenue Financed

11.1 Revenue financed solutions, are created for the provision of services and not specifically for the exclusive provision of capital assets such as buildings. For this reason, it is preferable to investigate revenue financed solutions as soon as possible after a user need has been identified rather than leaving it until a conventional construction project has been selected as the solution. It is possible that a revenue financed solution using such a model may result in a provision of services to meet the user need that does not require a construction project.

11.2 Due to the complexity of the contractual structure of a revenue financed project, it should be noted that the tendering process can be expensive for both potential service providers and the client, as this usually requires the negotiated or competitive dialogue procedure to be followed.

11.3 Use of a revenue funding model requires that the private sector assumes the risk and responsibility for both performance and availability of the contracted services – which may include the delivery of the building. The public sector sets out its service requirements in the form of an output specification which prescribes the level and quality of service required. This is normally done through a long-term contract and the standard of delivery is monitored by the public sector throughout the contract period, with deductions made from the monthly service payment where the specified outputs and standards are not delivered. Value for Money is achieved through private sector innovation, effective use of the competitive process, incentivisation of performance and appropriate allocation of risk to the party best able to manage it.

11.4 Where a revenue financed solution is being considered by the contracting authority, it is important that further advice is sought from Scottish Futures Trust at the earliest opportunity.

11.5 The potential benefits are:

- The process is service rather than project focused and concentrates on the whole life of the service and associated assets, rather than the construction phase alone.

- Avoids the use of a procuring authority’s capital finance.

- There is a single point of responsibility for service delivery.

- There is an opportunity to draw on a wider range of management and innovation skills.

- Appropriate risk transfer to the private sector partner for construction maintenance and lifecycle performance.

11.6 The potential risks are:

- The benefits of the contractual process will be at risk without a long-term commitment and monitoring from both the client and “service providers”.

- The process leading up to contract completion for the project can take a long time and needs an extensive and fully refined brief at the outset.

- There is a significant cost to bidders in tendering which may limit the level of interest in a project.

- Changes to existing contracts can be difficult to achieve after contract signature. In addition, changes to existing requirements can be time consuming and potentially expensive.

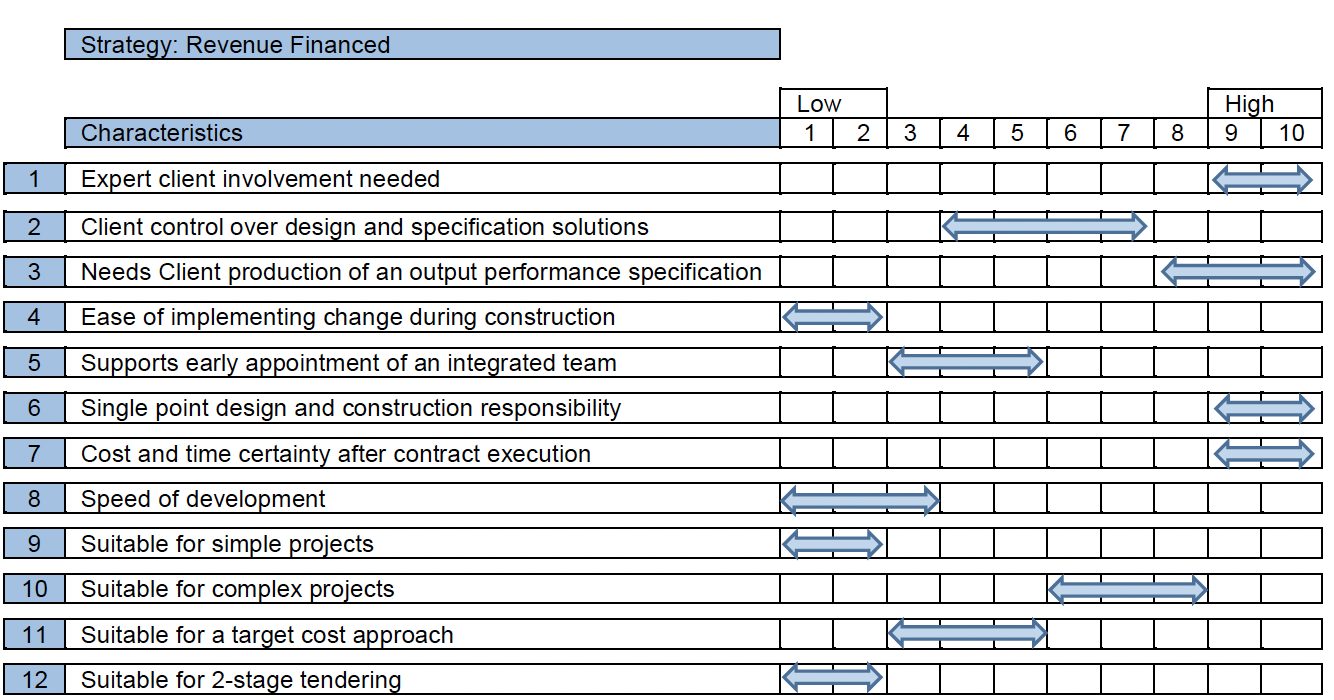

Figure 10: Characteristics of Revenue Financed Procurement Strategies

Variant: Two Stage Tendering

12.1 Two-stage tendering is used to allow early appointment of a contractor, prior to the completion of all the information required to enable them to offer a fixed price.

12.2 In the first stage, a limited appointment is agreed allowing the contractor to begin work and in the second stage a fixed price is negotiated for the contract. It can be used to appoint the main contractor early or more commonly as a mechanism for early appointment of a specialist contractor such as a cladding contractor. A two-stage tender process may also be adopted on a design and build project where the employer's requirements are not sufficiently well developed for the contractor to be able to calculate a realistic price. In this case, the contractor will tender a fee for designing the building along with a schedule of rates that can be used to establish the construction price for the second stage tender.

12.3 The basis of the appointment for the first stage may include:

- A pre-construction and construction programme.

- Method statements.

- Detailed preliminaries including staff costs.

- Agreed overheads and profit.

- A schedule of rates to be applied to the second-stage tender.

- Agreed fees for design and other pre-construction services.

- CVs for proposed site and head office staff.

- Tendering of any packages that can be broken out and defined.

- Agreed contract conditions to be applied to the second-stage construction contract.

12.4 It is important that this appointment is based on as much information as possible and that requirements are well defined; as subsequent changes could prove expensive.

12.5 The first-stage appointment might be made on the basis of a bespoke agreement, a consultancy agreement or a pre-construction services agreement (PCSA), with an appendix setting out all tender items to be applied to the construction contract, with a clause that makes it clear there is no obligation to proceed to the construction contract, and in such circumstances the pre-construction fee would be full and final settlement of the contractor's costs.

12.6 The pre-construction services carried out by the contractor in the first phase might include:

- Helping the consultant team to develop the design, or the contractor undertaking all design development themselves.

- Helping the consultant team to develop the method of construction, or the contractor developing the method of construction themselves.

- Obtaining prices for work packages from sub-contractors or suppliers on an open book basis.

12.7 In theory, this early involvement of the contractor should improve the buildability and cost-certainty of the design as well as creating a better integrated project team and reducing the likelihood of disputes.

12.8 Ideally the second-stage negotiation is a mathematical exercise using the pricing criteria agreed in the first stage agreement. In reality however, there will be some items not previously considered, around which negotiations will ensue. In the case of sub-contractors, the second stage construction contract is negotiated by the main contractor subject to the approval of the design team.

12.9 Two-stage tendering enables the client to transfer design risk to the contractor, however the client inevitably loses leverage as the contractor becomes embedded in the team and competition is less of a threat. However, whilst tender prices for two-stage contracts may initially be higher than single-stage tenders, which are subject to full competition, the final account tends to include fewer variations and fewer claims. A longer period of familiarity with the project creates better relationships as well as a reduction in learning curves and programme performance.

12.10 It is in the client's interests to try to include some packages in the first phase, and to ensure that they have some means of securing an alternative bid if negotiations with the preferred contractor fail, albeit this is likely to result in delays and difficulties regarding design liability. However, the client may find that alternative contractors lose interest once they find out that another contractor has been awarded the first stage tender.

12.11 The potential benefits are:

- Early appointment of the contractor, potentially bringing forward the completion date of the project;

- Second stage tender should be based on more complete information and a better understanding of the scope of works, so the final account should be closer to the contract sum;

- Improved identification of project risks within a timescale where action can be undertaken;

- Ability to procure specialist design contractor packages ahead of a first stage main contract tender that can then be incorporated into the second stage via novation;

- Client has no commitment beyond the preconstruction services agreement governing the first stage of the tendering process and through to the completion of stage two.

12.12 The potential risks are:

- Temptation to go to market with incomplete information;

- Can be used to mask the inadequacy of design development;

- Additional cost of a preconstruction fee;

- The cost of second stage tenders may be higher than predicted at Stage 1 leaving the client with difficult decisions on how to deliver within budget.

- Does not eliminate many sources of scope change;

- Increased input from client and consultants during the second stage tender;

- Difficulties in verifying the transparency of main contractor allowances and subcontractor costs;

- The contractor is able to walk away at any time.

Variant: Target Cost Contracts

13.1 Target Cost Contracts provide employers with a contractual mechanism to incentivise contractors to deliver projects within a specified budget. However, while this route may offer some advantages – for example, where a contract must be let before design development is sufficiently advanced to permit a lump sum price to be fixed – employers need to be aware that they are sharing a greater degree of risk in respect of a contractor’s performance under a target cost contract than they would under a fixed price contract. Therefore, it is important that employers considering using target cost contract approach have full regard to Scottish Procurement Construction Policy Note CPN 5/2017 – “Guidance on the operation of target cost contracts and pain share/gain share mechanisms”. This guidance provides an overview of the operation of target cost contracts and identifies a range of issues that need to be considered if such a strategy is to be adopted.

13.2 The basic principle underpinning this approach is that a “target cost” for the works is agreed between the employer and contractor, with the contractor then paid for the work undertaken on a cost reimbursable basis. The payments to the contractor are made on the basis of the contractor’s accounts and records, provided to the employer for inspection on an “open book” basis.

13.3 At the end of the project, the final target cost – which is the original target cost plus the effect of any changes and risk events the contracting authority is responsible for – is compared to the actual cost expended by the contractor. If the actual cost is lower than the target cost, a saving has been made, and this is shared between the parties on a pre-agreed percentage basis – referred to as “gain-share”. Conversely, if the actual cost is higher than the target cost there is an over-spend, again shared between the parties on a pre-agreed percentage split – referred to as “pain-share”.

13.4 The principal benefit of target cost arrangements is their ability to align the objectives of the parties, which helps to create a partnering environment. The contractor and contracting authority are both encouraged to work together to control costs, sharing the risk of over or under spend through the gain-share/pain-share mechanism. The open book approach helps to build trust between the parties, through the sharing of sensitive information by the contractor and the visibility to the contracting authority of the true cost of the project to the contractor.

13.5 However, one issue that often occurs is that target cost arrangements are entered into without fully understanding how the process works – in particular the additional risk that the contracting authority takes compared to a fixed price contract. It is vital that this risk is effectively managed. Too frequently there is insufficient control of the target cost value, so the contract becomes little more than a cost reimbursable arrangement with limited incentive for the parties to perform efficiently.

13.6 There are many examples where the actual cost has far exceeded the target cost, yet it appears there are few examples of contractors suffering from pain share. In most cases the gain-share/pain-share calculation results in a neutral or positive gain share.

13.7 Value for money will only be secured if the contract is let with a well-defined target cost and is thereafter very actively managed. Therefore, when considering a target contract, it is important the contracting authority recognises that it is carrying a larger degree of risk than a fixed price contract and therefore requires a greater resource to manage it.

13.8 Care is also needed when reporting likely outturn costs. It is not uncommon for a contractor, due to poor cost management of their supply chain, to under-estimate their final costs during the construction period only for a large amount of “actual cost” to come to light at the end of the project as sub-contractors present final account information. This can result in the contracting authority needing to secure approval for additional funding beyond the budget to cover the incurred costs.

13.9 In summary, target cost contracts will only deliver value for money when:

- The target cost is set at a level which requires the contractor and the contracting authority to work together to create efficiencies beyond those normally expected

- The target cost is actively managed and maintained so as to remain valid and to continue to drive performance

- The gain-share/pain-share mechanism is carefully chosen to drive the right behaviours in the parties to seek savings and thus avoid pain

- The contractor performs in an efficient manner, mitigating risk, and not incurring excessive actual cost

13.10 The potential benefits are:

- Provides contractors and subcontractors with an incentive to improve performance.

- Encourages active and equitable risk sharing, based on a clearly defined allocation of risk agreed at the outset of the project.

- Can incorporate both lump sum and prime cost-reimbursable subcontracts under a single target price.

- Target costs provide incentive for the timely administration of change control mechanisms.

- Provides an accountable mechanism to enable public sector clients to use incentives.

13.11 The potential risks are:

- The contracting authority and contractor must share “gain” and “pain” if the full benefits are to be secured. This exposes the employer to greater risk.

- Potential for failure on insufficiently defined projects owing to complexities in the operation of the incentive mechanism.

- Complex target price, gain/pain-share and change controls may not easily be understood by all parties.

- The separation of target and actual costs before completion creates the potential for loss of control in predicting the final cost to the employer.

- Requires best practice in project administration and a suitably skilled project manager.

- Disputes and adversarial behaviours can occur when the employer scrutinises the contractor’s cost records to ensure they are valid.

Variant: Frameworks

14.1 Framework agreements provide an option for contracting authorities which are procuring construction works on a regular basis and want to reduce procurement timescales, learning curves and other risks. In addition, a further benefit is the ability to build stronger long term working relationships between the client and contractor. Using a framework agreement allows the contracting authority to invite tenders from contractors and/or consultants over a period of time on a “call-off” basis as and when required.

14.2 The framework contract documents should define the scope and possible locations for the works or services likely to be required during the defined time period. They should describe the contract conditions that will be used for pre-construction services (such as design) and/or the contract conditions that will be used to execute the works. In addition, the contract documents should also identify the organisations permitted to use the framework.

14.3 Depending on the size and complexity of the anticipated projects, the supplier might provide a pricing mechanism or risk adjustment mechanism for different types of contract that might be used, for example, but not limited to, a minor works contract, a cost reimbursable contract or a design and build contract.

14.4 Framework tender documents might include:

- The starting and completion dates of the agreement.

- Requirements and obligations regarding insurance, bonds and warranties.

- A description of the contract conditions to be used and assumptions regarding preliminaries.

- A description of how the project will be managed in its various stages and the basis of remuneration.

- A description of the tender selection procedure and assessment procedure to be employed by the client.

- A description of inflation, interest and retention percentages to be applied.

- A description of incentive mechanisms to be applied.

- A description of dispute resolution procedures.

- Rates for travel and subsistence expenses.

- A request for schedules of rates and time charges to be submitted and a breakdown of resources and overheads to be applied to design, or manufacture and installation (including any proposed subcontractor or sub-consultant details).

- Any other criteria required from tenderers in order that the client can properly assess their suitability.

14.5 Following a competitive tendering process, one or more suppliers are then selected and appointed to the framework. When specific projects arise, the contracting authority is then able to simply select a suitable framework supplier and instruct them to start work.

14.6 Where there is more than one suitable supplier available, the contracting authority may introduce a secondary selection process to assess which supplier is likely to offer best value for a specific project. The advantage to the contracting authority of this process is that they are able instigate a selection procedure for individual projects without having to undertake a time-consuming pre-qualification process. This should also reduce tender costs.

14.7 The advantage to the supplier is that the likelihood of them being awarded a project when they are already on a framework contract should be higher than it would be under an open procurement process. Some suppliers, however, complain that having already been appointed on a framework agreement, they may still have to bid for individual projects, with a result that the potential efficiency gains of this process are lost.

Selecting a Procurement Strategy and a Form of Contract

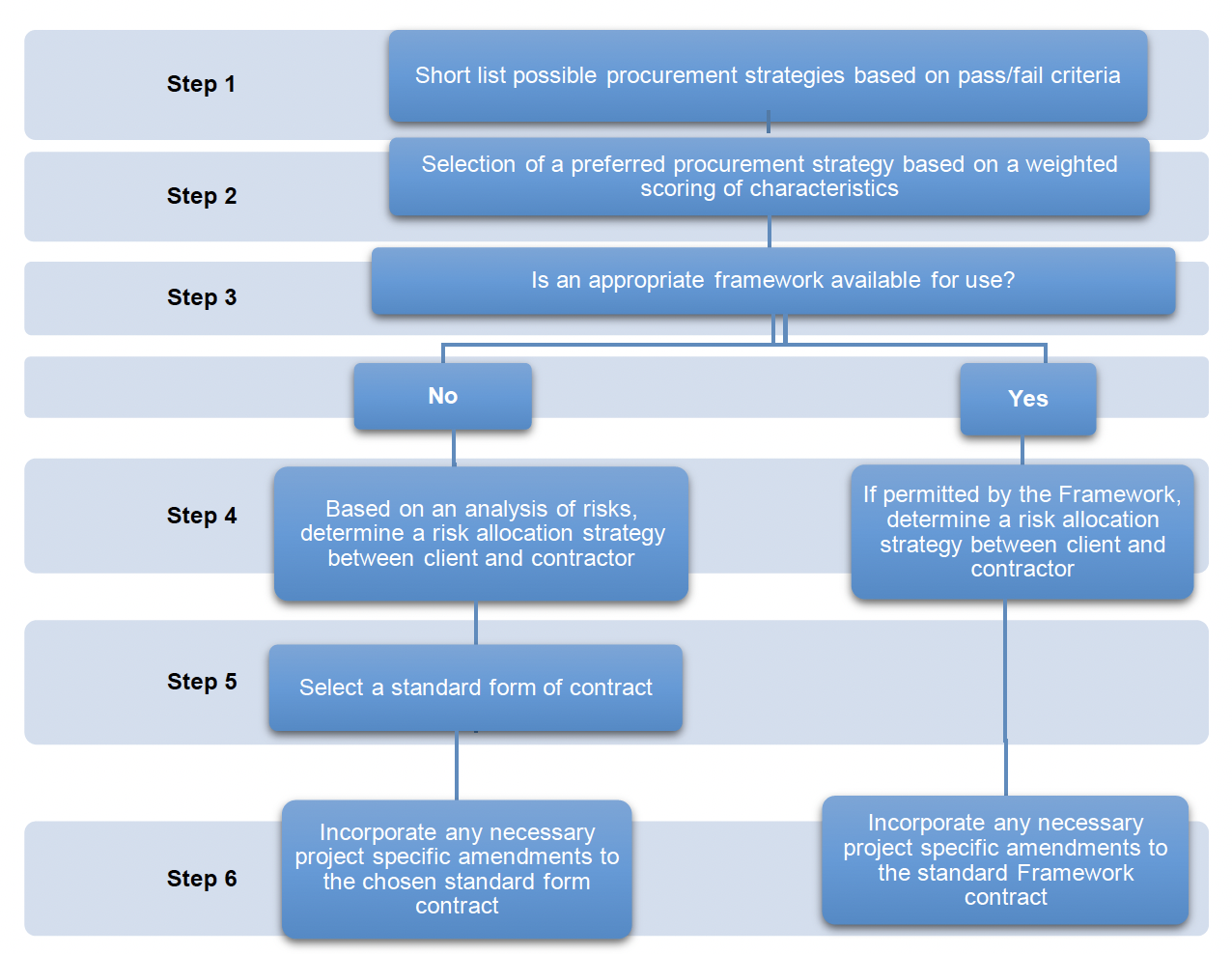

15.1 A suggested approach to assist in the selection of an appropriate procurement strategy and a form of contract is shown diagrammatically below in Figure 11 and each step is then described in later sections of this guidance. Contracting authorities should also take advice from their professional advisers.

Figure 11: A Suggested Approach for selecting a Procurement Strategy and Form of Contract

Short List Procurement Strategies Based on Pass/Fail Criteria

16.1 Some procurement strategies are only suitable for certain types of project, and for contracting authorities with expert and experienced construction procurement resource availability. It is therefore important that contracting authorities undertake a project specific analysis of the relative characteristics (as described previously in this chapter) of the various procurement strategies to help inform their decision on which strategy they should adopt for the project in question.

16.2 As a first step in this analysis, it is suggested that an initial short list of possible procurement strategies is drawn up by testing 6 of the characteristics listed in Figure 12 against a simple pass/fail process. The criteria recommended for this process are:

- Is expert client involvement needed due to the complex nature of the strategy? (Shown as Characteristic No 1 on Figure 12)

- If required, does the strategy support the early appointment of an integrated team? (No 2 on Figure 12)

- Is the strategy suitable for low value, simple projects? (No 3 on Figure 12)

- Is the strategy suitable for complex projects? (No 4 on Figure 12)

- If required, does the strategy support the operation of a target cost approach? (No 5 on Figure 12)

- If required, does the strategy support a two-stage tender approach for the main contractor? (No 6 on Figure 12)

- In addition to the above, a further test (No 7) is recommended as follows:

- Is the contracting authority a Participant in the hub programme?

16.3 Two worked examples are shown below to demonstrate the process

- Example 1, a simple project for a contracting authority not possessing expert construction procurement professionals; and,

- Example 2 – a complex project for a contracting authority which possesses expert knowledge and wants to develop a design solution collaboratively with an integrated team.

To assist, Figure 12 sets out how each of the various procurement strategies meet the pass/fail criteria listed in paragraph 16.2 above.

| Procurement Strategies | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pass/Fail Criteria | Early Integrated Team | Traditional | Design & Build | Design Develop & Construct | hub | Construction Management | Management Contracting | Revenue Financed |

| 1. Expert contracting authority involvement needed | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 2. Supports the early appointment of an integrated team | Yes | No | Single Stage - No Two Stage - Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| 3. Suitable for simple projects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

| 4. Suitable for complex projects | Yes | Yes (if two stage) | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 5. Suitable for a target cost approach | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

| 6. Suitable for 2-stage tendering | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Consider1 | No | No | No |

| 7. The contracting authority is not a hub participant or shareholder | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Not Applicable |

1 * The hub programme contains many of the characteristics of 2-stage tendering.

Example One

17.1 A simple project for a contracting authority not possessing expert construction procurement professionals. Only three strategies are considered suitable non-expert contracting authorities, which are:

- Traditional;

- Design and Build; and,

- Design, Develop and Construct.

17.2 A weighted, project specific scoring analysis of the options will help the client to select the most appropriate strategy for the project in question. Where the contracting authority has signed a Territory Partnership Agreement with its local hubCo, the further option of a hub procurement strategy is available to it.

17.3 Finally, if the contracting authority has some expertise in this area, it may also wish to consider using a target cost approach or a 2-stage tendering approach.

Example Two

18.1 A complex project for a contracting authority which possesses expert knowledge, and which wants to develop its design solution collaboratively with an integrated team. Only five strategies are suitable for integrated teams, and of these four are suitable for complex projects:

- Early Integrated Team;

- Hub (where the contracting authority has signed a Territory Partnership Agreement);

- Construction Management; and,

- Management Contracting.

18.2 Once again, a weighted, project specific scoring analysis of the options will help the client to select the most appropriate strategy for the project in question.

Select from Short List Based on a Weighted Scoring of Characteristics

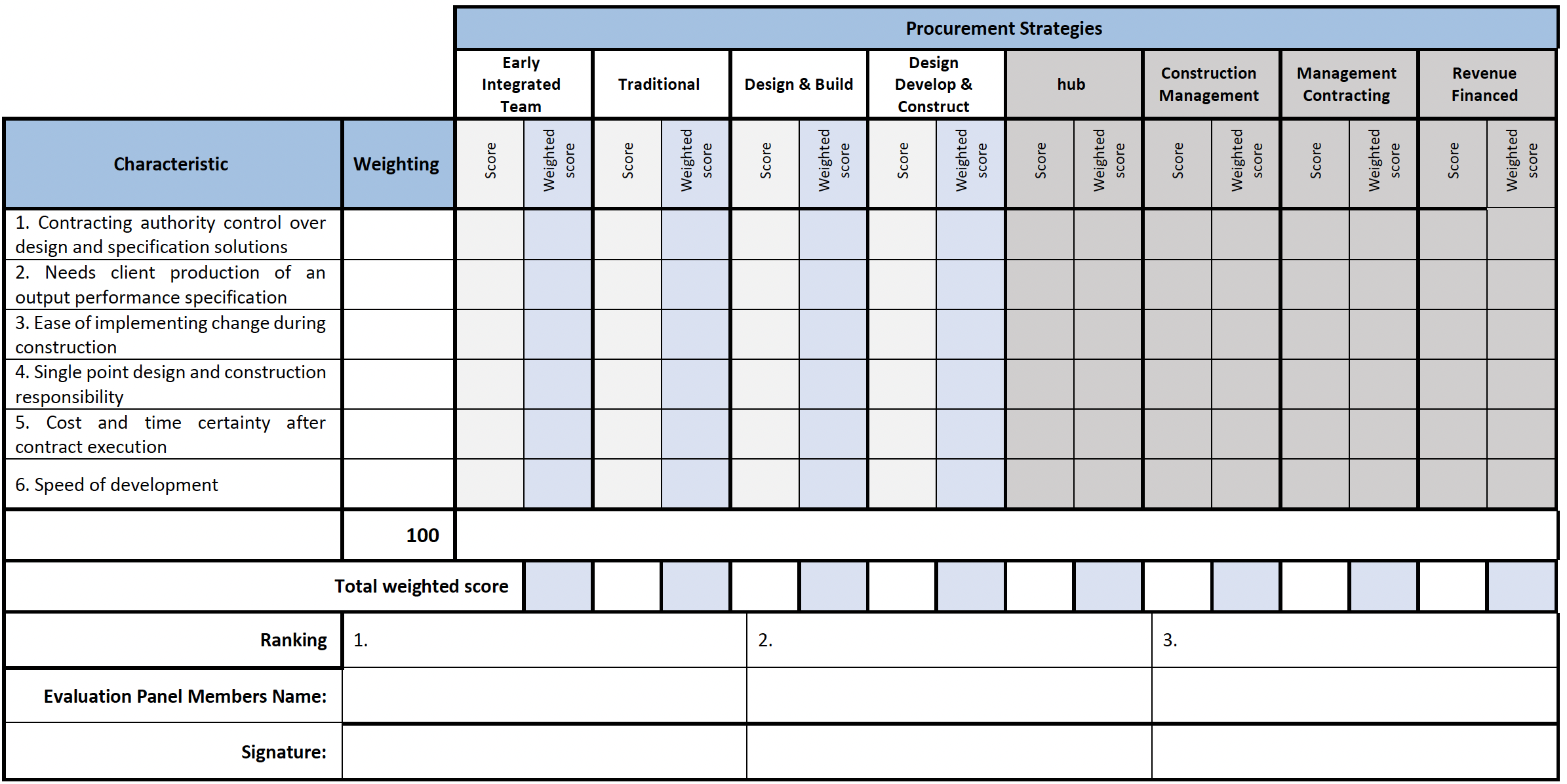

19.1 Earlier in this chapter, each procurement strategy description ends with a matrix of 12 characteristics, scored as a range from 1 (low) to 10 (high). This matrix can be used as a tool to help inform a contracting authority’s decision making process as to which procurement strategy might be appropriate for its particular needs as follows:

- Six of these characteristics have been used for the pass/fail criteria in order to develop a strategy short list. The other six can now be used as part of a weighted scoring system to select the best fit strategy for the particular project.

- It will be for the contracting authority to determine the weighting of these six criteria, and subsequently the score to be applied to each short-listed strategy. The individual scores should not sit outside of the ranges suggested earlier in this chapter.

19.2 To illustrate the process, a suggested weighting split for each for each of the 6 characteristics of three generic project types is shown in Figure 13. However, the contracting authority should select their own weightings based on the specific circumstances of the project. Finally, template for the weighted scoring exercise is shown at Figure 14.

| Characteristic | Description | Example Weightings | Project Score | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simple project, low value and risk, no expert client availability | Complex, high value and risk, expert client available | Speed essential, comfortable with higher risk, expert client available | |||

| Client control over design and specification solutions (Shown as Characteristic No 1 on Figure 14) | The amount of control afforded to the client in selecting a preferred design solution rather than simply testing if the specified outcomes are achieved by a proposed design. | 20 | 25 | 20 | |

| Needs contracting authority production of an output performance specification (Shown as No 2 on Figure 14) | The extent to which the procurement strategy is reliant on a detailed set of client technical requirements expressed as achieving minimum performance levels. | 0 | 10 | 10 | |

| Ease of implementing change during construction (Shown as No 3 on Figure 14) | The ease of instructing a change and of agreeing any implications of cost and time | 15 | 10 | 10 | |

| Single point design and construction responsibility (Shown as No 4 on Figure 14) | The extent to which responsibility for design and construction is contractually aligned | 15 | 20 | 20 | |

| Cost and time certainty after contract execution (Shown as No 5 on Figure 14) | Measures the degree to which construction phase risks are able to be transferred to the contactor | 35 | 25 | 15 | |

| Speed of development (Shown as No 6 on Figure 14) | A measure of the relative speed from project inception to start of construction | 15 | 10 | 25 | |

| 100 | 100 | 100 | |||

19.3 Once a procurement strategy has been selected, the contracting authority should then give consideration to whether it is eligible to use an existing appropriate framework which uses the same strategy. If it does not, a new contractor procurement exercise must be undertaken.

Figure 14: Example weighted scoring. Note: Only those procurement strategies remaining after the pass/fail test should be scored.

Introduction to Risk Management and Apportionment

20.1 The recommendations of the Review of Scottish Public Sector Procurement in Construction made clear that risk should lie with the party most able to understand and manage it. If that is the contractor, it should have an opportunity to understand and price the risk. In this context, “risk” should be understood as relating to the procurement process itself or specific contracts within it, considered as a sub-set of the overall project/programme risk.

20.2 If risks do materialise, and they have not been adequately priced, this can result in undesirable behaviours between the contracting parties and a breakdown in the partnering relationship. In a more extreme situation, especially where risks have been forced down the supply chain, this could result in insolvencies, the impact of which could create a significant disruption to the planned programme.

Risk Apportionment

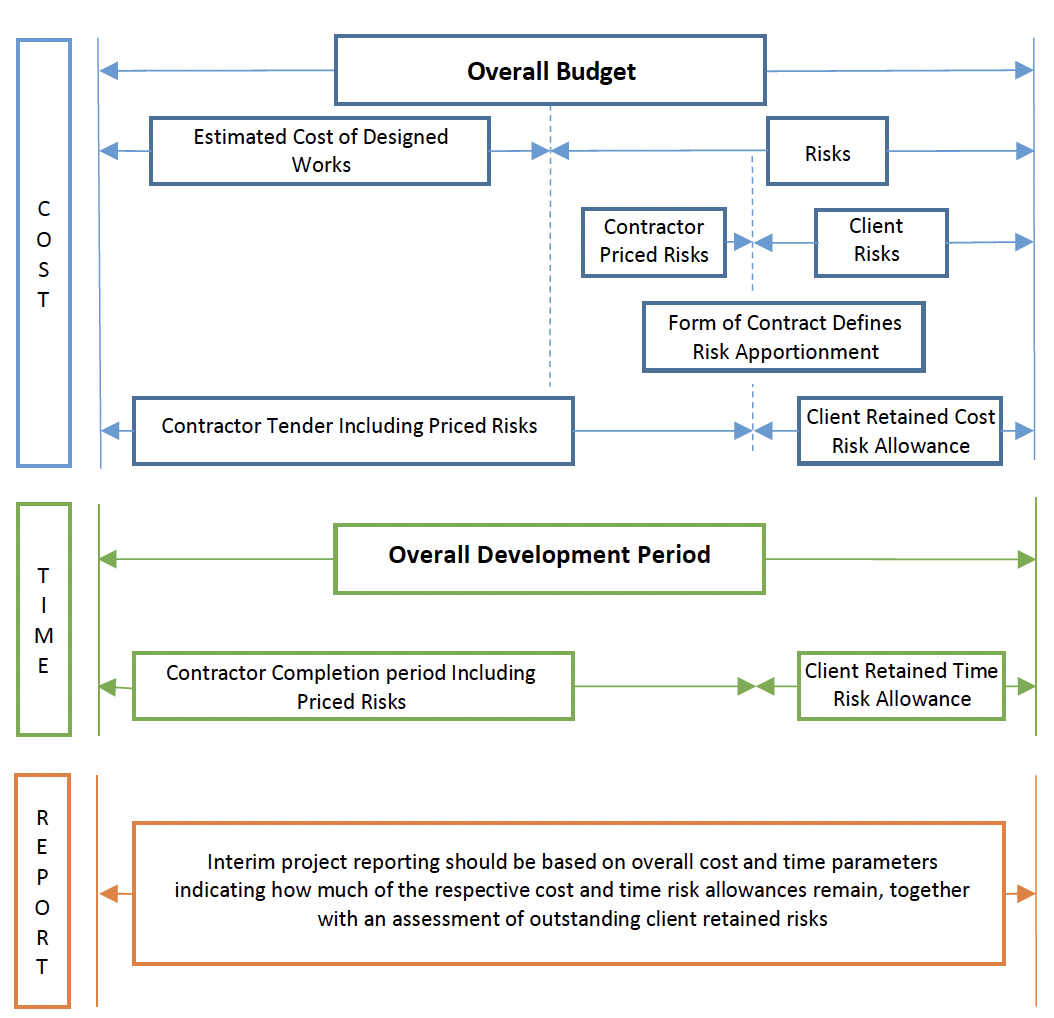

21.1 The following diagram Figure 15 illustrates the principles of risk apportionment between client and contractor. Note that the primary purpose of the form of construction contract is to define risk apportionment.

Figure 15 – Principles of risk apportionment

Risk Management

22.1 The key to successfully managing design and construction risks is to adequately determine and implement mitigation strategies from the earliest point in a project.

22.2 Examples include:

- The earliest commissioning of comprehensive surveys (with optional transferable warranties in favour of a future contractor) including, but not limited to, ground conditions, contamination, utilities, ecology and archaeology.

- Establishing a coherent strategy for design coordination between client employed consultants and specialist contractor designed elements.

- Establishing a strategy for the responsibility for securing statutory consents.

- Where it is planned to place responsibility on a design and build contractor for previous design work carried out by others, how this can best be de-risked from the contractor’s perspective.

22.3 The following, Figure 16, is an example of a template which a contracting authority can use as a tool to address these issues. In the case of an actual project, the contracting authority should start with a blank template.

| Example of a risk | Example of a possible mitigation strategy | Consider Client Owned? Contractor Owned? Insurance? | Information needed to price the risk, whomever owns it |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ground Conditions, Contamination | 1. Commission comprehensive surveys with transferable warranties of duty of care | contracting authority or contractor depending on form of contract chosen | 1. Results of surveys 2. Copies of warranties 3. Possible follow up surveys |

| Piling Obstructions | 1. Ground radar survey 2. Ground probing exercise | To be priced by contractor. Then consider value for money. | Results of surveys and probing exercise |

| Utility Connections | 1. Ground radar survey 2. Hand dug trial holes 3. Early client application for supply infrastructure | To be priced by contractor. Then consider value for money. | 1. Information from surveys. 2. Quotations from utility infrastructure providers |

| Design is in insufficient detail to price works accurately | 1. Define level of detail in consultant services 2. Monitor a detailed design and coordination programme 3. Review detail two weeks before tender 4. For specialist contractor designed elements, consider 2-stage tenders | Contractor owned (preferred) contracting authority owned if a traditional, re-measured procurement strategy. | 1. Review available design information - assess for level of detail and evidence of coordination 2. Review forms of consultant appointments, check liability obligations and scopes of service. |

| Damage to adjoining properties | 1. Dilapidation surveys to establish condition | Insurance taken out by client. | Results of surveys. |

22.4 Where it is considered desirable to transfer such risks to the contractor, contracting authorities should preferably establish the cost of doing so. This can be done by seeking provisional prices at tender stage for the effect of transferring each risk. The more successful each mitigation strategy has been, the lower the price should be.

22.5 Dialogue with all of the tendering contractors, or prior to tender with the market more generally, will inform contracting authorities on how best to present tender information such that risks are priced as economically as possible.

22.6 Contracting authorities should take appropriate legal advice to ensure such pre-tender dialogue with contractors complies with the relevant procurement regulations.

22.7 On more complex projects, contracting authorities may wish to make the process of risk apportionment a negotiation with each bidder prior to submission of their final offer. The Competitive Procedure with Negotiation or, exceptionally, the Competitive Dialogue procedure can be used in these circumstances.

Amendments to Standard Form Contracts

23.1 The Review of Scottish Public Sector Procurement in Construction noted with concern the prevalence of wholesale amendments introduced by public bodies to standard form construction contracts. The Review concluded this practice is often intended to transfer more risk on to the contractor. While in some situations this may be appropriate, this is not always the case. Risk should lie with the party most able to understand and manage it; and if that is the contractor, then they should be afforded the opportunity to price the work accordingly. If contractors are required to carry risks without being able to factor them into their prices then there is a very real danger of these encourage undesirable behaviours, such as cutting corners on quality in order to recoup the cost back from elsewhere.

23.2 The Review noted that the amendment of contracts presents two further main risks. Firstly, that additional clauses may be incompatible with the remainder of the contract. This may lead to contractual disputes or to clients being liable for costs which they thought they had passed to the contractor. Secondly, as the complexity of the contract increases, parties to it face increasing legal costs. The addition of inappropriate or unnecessary amendments simply exacerbates this problem.

23.3 Therefore, it is recommended that any variations to standard forms of contract should be kept to a minimum and used only when absolutely necessary to take account of the particular circumstances of a project. It is also recommended that where a contracting authority considers that amendments may be required, it should consult with its legal advisers to understand the likely consequences and impact of its proposed amendments to the parties to the contract and the contractor’s supply chain.

23.4 Finally, it is also recommended that any amendments introduced should be clearly highlighted within the contract documentation so that both client and contractor are clear on the variations being made to the standard terms. The original text of a clause should be typed with any deletions struck through, and any additional text highlighted. Also, a schedule should be prepared which explains why the amendments are required. This will help contractors by significantly reducing the amount of time and additional cost they will incur in considering the effect of the amendments.

23.5 A contracting authority must be mindful that the greater the number of amendments made, the greater the risk of disputes arising. This is due either to differences in interpretation or to the amendments being incompatible with the remainder of the contract. There is also a danger that the personnel administering the contract, for both parties, are not intuitively aware, or understand, the effect of the amendments.

23.6 Figure 17, below, provides examples of the type of amendments which should not normally be considered as appropriate along with reasons not to amend the standard form of contract.

Proposed Amendment

Different or more onerous payment or retention arrangements

Reasons not to Amend

The payment terms in standard contracts are fair and comply with the requirements of the Procurement Reform (Scotland) Act 2014. Authorities must recognise their responsibilities for maintaining a sustainable industry and understand the importance of cash flow to contractors and sub-contractors. The Procurement Reform (Scotland) Act 2014 also requires authorities to introduce measures to ensure maximum 30-day payments throughout the supply chain.

Proposed Amendment

Different or more onerous periods for the issue of contract notices

Reasons not to Amend

The periods in standard contracts are fair and are familiar to contractors and sub-contractors. Amendments present the particular risk that tier 2 and 3 contractors may miss notice dates and become unfairly and disproportionately penalised.

Proposed Amendment

Different or more onerous dispute resolution procedures

Reasons not to Amend

Any amendments which extend periods for dispute resolution, or present barriers to its access, are disproportionately unfair to small businesses - particularly in securing payments.

Proposed Amendment

Responsibility for the consequences of changes in law or statutory regulations after a contract is executed.

Reasons not to Amend

Such an amendment presents a risk that cannot be either understood or priced at the time of tender. The consequences will likely be stepped down the supply chain to businesses that are not equipped to take such risks.

Figure 17. Examples of contract amendments for risk transfer which should not normally be considered.

23.7 Figure 18 provides examples of common amendments which should only be introduced if information is provided at the time of tender to allow the main contractor and its sub-contractors to both understand and price the risk being transferred from the authority.

Proposed Risk Transfer

Ground conditions, contamination, archaeology

Considerations

Each tendering contractor should be given sufficient time to study site investigation reports and have an opportunity to request further investigations. Pre-market engagement is recommended. Dark ground risk, e.g. under existing buildings, should always remain with the authority.

Proposed Risk Transfer

Effect of adverse weather conditions

Considerations

If standard terms are proposed to be amended – for example to introduce a 1:10 year weather event test – there should always be a backstop after which the authority retains the risk.

Proposed Risk Transfer

Establishing specific completion criteria

Considerations

Any amended criteria for determining when completion is achieved should be clear and objective such that disputes on interpretation are avoided.

Proposed Risk Transfer

Availability of utilities

Considerations

Such risk transfer should only be considered if quotations for supply are available from utility providers at the time of tender. Pre-market engagement recommended.

Proposed Risk Transfer

Securing statutory approvals, other than planning consent

Considerations

Pre-market engagement is recommended. For a conventional design, this may be a reasonable risk transfer. If, however the design is complex, or will rely on relaxations to regulations - perhaps with cost implications - it should be avoided.

Proposed Risk Transfer

Compliance with Planning Conditions

Considerations

Risk transfer should only be sought for those conditions which can be delivered by the contractor without reliance on the actions of the authority. Pre-market engagement is recommended.

Proposed Risk Transfer

Responsibility for previous design work

Considerations

This is common in the case of an authority’s design team being novated to a design and build contractor. In other circumstances, it should only be considered for conventional designs and with sufficient time for the contractor to carry out due diligence.

Proposed Risk Transfer

Compliance with 3rd party contract obligations e.g. covenants, wayleaves, rights of way

Considerations

Such obligations should always be referenced by a detailed schedule at the time of tender and not by simple notification of the existence of a 3rd party contract.

Figure 18: Examples of contract amendments for greater risk transfer – but only with an opportunity for the contractor and its supply chain both to understand and to price the risk at the time of tendering.

Selecting a Form of Contract

24.1 Once a procurement strategy is selected and a risk allocation strategy is prepared, the final step is to choose a form of contract. Figure 1, earlier in this chapter, notes of variety of forms of contract which might be selected for a particular procurement strategy. Contracting authorities are encouraged to consider all available forms, not relying solely on familiarity or previous use, and to take advice from their professional advisers in arriving at the most appropriate selection.

Standard Form Construction Contracts

25.1 There are many different standard form construction contracts available for use in the UK market. This guidance note only considers those most often used. These are contracts published by:

- The Joint Contracts Tribunal (JCT), one of whose members is the Scottish Building Contract Committee (SBCC) which produces equivalent, very similar, contracts for use in Scotland.

- The NEC, which is a division of Thomas Telford Ltd, a wholly owned subsidiary of the Institution of Civil Engineers.

- The Association for Consultancy and Engineering (ACE) and the Civil Engineering Contractors’ Association (CECA) which jointly publishes the Infrastructure Conditions of Contract (ICC). These are effectively re-prints of the now abandoned ICE Conditions of Contract.

- The Association of Consultant Architects (ACA) publishes contracts specifically drafted for integrated team/partnering arrangements.

Other Contracts

26.1 Other, less often used, contracts are published by:

- The Institution of Chemical Engineers produces a suite of contracts used mostly in process industries.

- FIDIC (International Federation of Consulting Engineers) publishes a suite of contracts used internationally, and by the World Bank. If contemplating use in the UK, amendments would be needed to comply with UK legislation requirements.

- The Institution of Mechanical Engineers and the Institution of Engineering and Technology produce contracts for electrical and mechanical work.

- The Chartered Institute of Building has launched a contract for use with Complex Projects – CPC 2013.

- Scottish Futures Trust publishes contracts for use on revenue financed schemes, and for design and build projects using the hub programme.

Commonly Used Contracts

27.1 The most commonly used contracts for each type of procurement strategy are listed in turn in the following paragraphs.

27.2 Traditional Contracts:

- JCT (SBCC) Standard Building Contract 2011 (in versions of with quantities, without quantities, and with approximate quantities)

- JCT (SBCC) Intermediate Building Contract 2011

- JCT (SBCC) Minor Works Building Contract 2016

- JCT Measured Term Contract

- NEC 3 ECC Option A (lump sum) or Option B (with quantities)

- ICC Minor Works 2011

- ICC Measurement Version 2011

- ICC Crown Investigation Version 2011

27.3 Design and Build:

- JCT (SBCC) Design and Build Contract 2016

- JCT Major Project Construction Contract 2011

- NEC3 ECC Options A-E

- ICC Design and Construct Version 2011

27.4 Management Forms:

- JCT Management Contract 2011

- JCT Construction Management 2011

- NEC3 ECC Option F

27.5 Integrated Team (Partnering):

- PPC 2000 (2013 edition)

- NEC3 ECC with Option X12

- JCT Constructing Excellence 2014

- ICC Partnering Addendum

27.6 Cost Plus/Cost Reimbursable/Prime Cost:

- JCT Prime Cost 2011

- NEC ECC Option E

27.7 Target Cost

- NEC 3 ECC Options C and D

- ICC Target Cost

JCT (SBCC) or NEC?

28.1 For building projects, unless an Integrated Team or Revenue Financed procurement strategy has been chosen, the procuring authority will mostly find it needs to choose between a JCT (SBCC) or a NEC form of contract. Advice should always be sought from professional advisers to assist in making that decision, however care should be taken to ensure such advice is impartial, avoiding any consultant self-interest.

Choosing from the Differing Forms of Contract

29.1 The JCT provides a wide range of different forms depending on the procurement route (traditional contracting, design and build, management contracting, etc) and the size and complexity of the project. The NEC starts from the reverse position: there is a single common form of main contract and flexibility is obtained by selecting one of the main pricing ‘Options’ (lump sum, target cost, etc.) and then from an extensive range of secondary clauses dealing with matters such as delay damages, sectional completion, limitation of liability and key performance indicators.

Management of the Contract