Scottish household survey 2018: annual report

Results from the 2018 edition of the continuous survey based on a sample of the general population in private residences in Scotland.

10 Environment

Main Findings

Climate change

Since 2013 there has been a steady increase in adults viewing climate change as an immediate and urgent problem, from less than half (46 per cent) to nearly two thirds (65 per cent) of adults. The largest increase in those who agreed with this is amongst 16-24 year olds, increasing from 38 per cent to 67 per cent.

In 2018, the proportion of adults with a degree or professional qualification who perceived climate change as an immediate and urgent problem was double that of adults with no qualifications (81 per cent compared to 40 per cent).

In 2018, around three quarters (74 per cent) of adults agreed that they understood what actions they should take to help tackle climate change with an increase from a quarter (26 per cent) to a third (34 per cent) of those who strongly agreed with this since 2015.

Visits to the outdoors and greenspace

More than half of adults (59 per cent) visited the outdoors at least once a week in the last year, an increase from 52 per cent in 2017. The 2018 figure is the highest percentage observed since the start of the time series in 2012.

Adults living in the most deprived areas were more likely not to have made any visits to the outdoors in the past 12 months (18 per cent) compared to those in the least deprived areas (five per cent).

Most adults (65 per cent) lived within a five minute walk of their nearest area of greenspace, a similar proportion to 2017 and 2016. A smaller proportion of adults in deprived areas lived within a five minute walk of their nearest greenspace compared to adults in the least deprived areas (58 per cent compared to 68 per cent).

Participation in land use decisions

In 2018, less than a sixth of adults (15 per cent) reported that they gave their views on land use, the same proportion as in 2015 and 2017.

A greater proportion of adults living in rural areas reported giving their views on land use compared to adults living in urban areas

The most common way in which people reported giving their views on land use was by signing a petition (seven per cent of adults) and the least common was through discussions with a land owner or land manager (one per cent of adults).

10.1 Introduction and Context

The Scottish Government and partners are working towards creating a greener Scotland by improving the natural and built environment, and protecting it for present and future generations. Actions are being taken to reduce local and global environmental impacts, through tackling climate change, moving towards a zero-waste Scotland through the development of a more circular economy, increasing the use of renewable energy and conserving natural resources. The Scottish Government is also committed to promoting the enjoyment of the countryside and of green spaces in and around towns and cities.

The updated National Performance Framework, published in June 2018, contains a National Outcome for the environment[107]: We value, enjoy, protect and enhance our environment.

A range of National Indicators have been developed to track progress towards this environmental outcome. Two of these indicators, ‘visits to the outdoors' and ‘access to green and blue space’, are monitored using data from the Scottish Household Survey (SHS). “Access to green and blue space” is measured using the greenspace question which defines greenspaces as “public green or open spaces in the local area, for example a park, countryside, wood, play area, canal path, riverside or beach”.

Some local authorities also use the SHS to assess progress towards environmental objectives, including those in their Single Outcome Agreements[108] (a statement of the outcomes that they want to see for their local area).

This chapter begins by exploring attitudes towards climate change. It then looks at visits to the outdoors and access to local greenspace. Finally it examines participation in land use decisions.

Responses to questions on litter and dog fouling are found in Chapter 4 ‑ "Neighbourhoods and Communities".

10.2 Attitudes to Climate Change

10.2.1 Introduction and Context

There is a global climate emergency, and the Scottish Government is acting accordingly. The Climate Change (Scotland) Act 2009 set a target of reducing Scotland’s greenhouse gas emissions by 42 per cent by 2020 and 80 per cent by 2050, compared with the 1990 baseline. A Bill to amend that Act is currently before Parliament. This Bill includes amendments that set a net-zero emissions target for 2045 and increase the targets for 2030 and 2040. It increases the level of ambition in the climate change targets in response to both the 2016 United Nations Paris Agreement on climate change and the updated advice received in May 2019 from the UK Committee on Climate Change in light of the 2018 report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). An update to the Scottish Government’s current Climate Change Plan will be published within six months of the Bill receiving Royal Assent.

The Scottish Government recognises that public understanding, engagement and action will be critical to achieving the social and economic transformations required to transition to a net-zero society and to meet climate change targets. In June 2019, the Scottish Government launched ‘The Big Climate Conversation’ to engage with the public, communities, businesses, industry, and the public sector in a discussion about what more can be done. The responses from these events will also inform a revised Public Engagement Strategy, which will encourage and assist the Scottish public in transitioning to net-zero emission lifestyles.

Since 2013, the SHS has included a question about perceptions of climate change as a problem. In 2015, the SHS also added four new questions to explore people’s perceptions relevant to action to tackle climate change. Following a recent review of the SHS questionnaire, these four questions are now asked in even years and so the next data available will be for 2020, which is expected to be published in 2021.

10.2.2 Attitudes towards Climate Change as a problem

Respondents were presented with four different statements about the problem of climate change and asked which, if any, came closest to their own view. Table 10.1 shows that the proportion of adults who viewed climate change as an immediate and urgent problem increased by more than one third between 2013 and 2018, from 46 per cent to 65 per cent.

Table 10.1: Perceptions about climate change as a problem

Column percentages, 2013-2018 data

| Adults | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate change is an immediate and urgent problem | 46 | 45 | 50 | 55 | 61 | 65 |

| Climate change is more of a problem for the future | 25 | 26 | 23 | 23 | 18 | 16 |

| Climate change is not really a problem | 7 | 8 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 |

| I'm still not convinced that climate change is happening | 13 | 11 | 11 | 9 | 8 | 7 |

| No answer | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Don't know | 7 | 6 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 7 |

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Base | 9,920 | 9,800 | 3,100 | 3,150 | 3,160 | 3,090 |

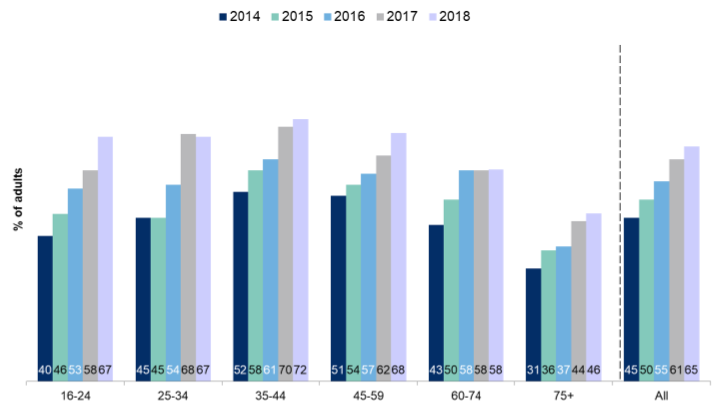

The perception of climate change as an immediate and urgent problem varied by age, educational attainment and area deprivation. Figure 10.1 shows that the perception of climate change as an immediate and urgent problem was highest among 35–44 year olds (72 per cent), and has been consistently lowest among the oldest age group, 75+ (46 per cent). While this perception has increased among all age groups over time, the largest increase has occurred among the youngest age group (16–24 year olds). For the first time since this time series began, the proportion of 16-24 year olds who viewed climate change as an immediate problem (67 per cent) was higher than the proportion across all age categories (65 per cent).

Figure 10.1: Percentage of adults perceiving climate change as an immediate and urgent problem by age over time

2014-2018 data, Adults (2018 minimum base: 230)

2013 data has been omitted from this graph to aid visual interpretation. The 2013 results are in line with the trend shown (16-24: 38 per cent; 25-34: 47 per cent; 35-44: 54 per cent; 45-59: 51 per cent; 60-74: 42 per cent; 75+: 33 per cent; All: 46 per cent).

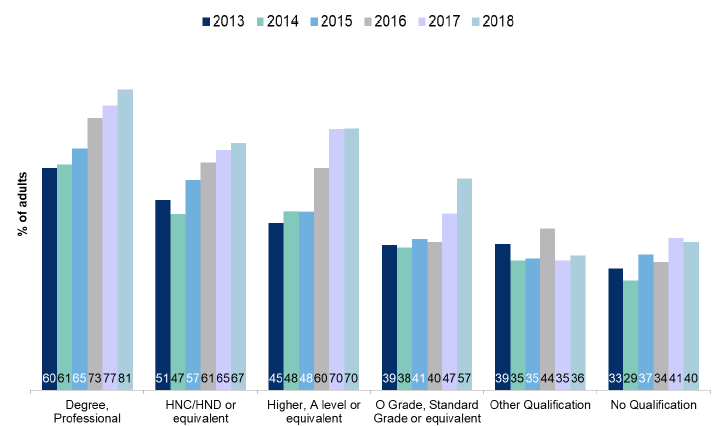

Figure 10.2 shows that the proportion of adults perceiving climate change as an immediate and urgent problem tended to be higher amongst those with a higher level of qualification. In 2018, the proportion of adults with a degree or professional qualification who perceived climate change as an immediate and urgent problem was double that of adults with no qualifications (81 per cent compared to 40 per cent). The proportion who perceived climate change to be an immediate and urgent problem has increased over time in both these groups, however, the relative increase over time has been greater for adults with a degree or professional qualification (increasing by over a third from 60 per cent in 2013 to 81 per cent in 2018) than for those with no qualifications (increasing by approximately one fifth from 33 per cent to 40 per cent).

Figure 10.2: Perceptions about climate change as a problem by educational attainment

2013-2018 data, Adults (2018 minimum base: 150)

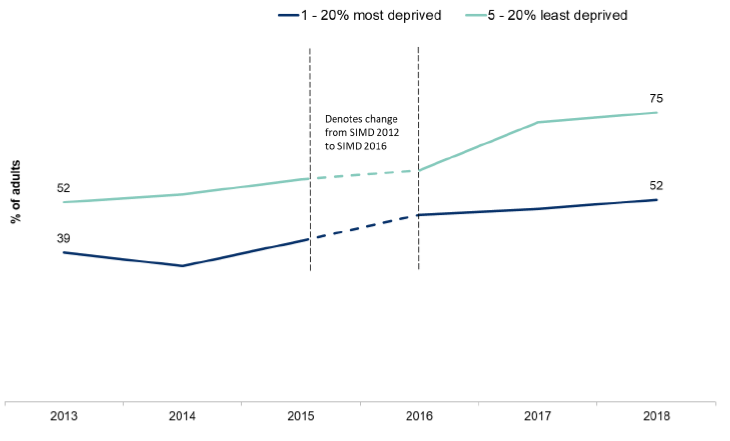

Climate change was more likely to be perceived as an immediate and urgent problem by adults living in the least deprived quintile (75 per cent), compared with adults living in the most deprived quintile (52 per cent). Figure 10.3 shows that this gap has persisted since 2013. Whilst the proportion of adults perceiving climate change to be an immediate and urgent problem has increased over time among adults in both the most and least deprived quintiles, this increase has been greater in the least deprived quintile, resulting in a widening of the gap over time.

Figure 10.3: Perceptions about climate change as a problem for 20% most and 20% least deprived areas

2013-2018 data, Adults (2018 minimum base: 570)

10.2.3 Attitudes towards taking action to tackle Climate Change

People’s attitudes towards taking action to address climate change will be influenced by, amongst other things, their views about whether climate change will affect Scotland; whether their everyday behaviours and lifestyles contribute to climate change; whether any actions they take would have an impact on climate change; and whether they know what actions to take personally. Respondents’ views were explored by inviting them to agree or disagree with four statements, which vary in terms of whether agreement or disagreement represents a favourable attitude towards taking action to tackle climate change.

10.2.3.1 The value of individual actions to help the environment

Respondents were asked to agree or disagree with the statement: “It’s not worth me doing things to help the environment if others don’t do the same”. Disagreement with this statement suggests a positive perception of the value of individual actions, regardless of the actions of others.

Table 10.2 shows that, in 2018, two out of three of adults disagreed with this statement. The most substantial change with time has been the proportion of adults who strongly disagreed, which has increased by 15 percentage points between 2015 and 2018 (from 31 per cent to 46 per cent). Over the same time period, there has been a decrease in the proportion of adults stating that they tend to disagree (from 31 to 21 percent), which suggests a strengthening of public opinion amongst those who disagreed. There has also been a decrease in the proportion of those who tended to agree with this statement between 2015 and 2018 (from 17 to 10 per cent), while the proportion of adults who strongly agreed has remained consistently very low (five or six per cent).

Table 10.2: “It’s not worth me doing things to help the environment if others don’t do the same”

Column percentages, 2015, 2017 and 2018 data

| Adults | 2015 | 2017 | 2018 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strongly agree | 5 | 6 | 5 |

| Tend to agree | 17 | 14 | 10 |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| Tend to disagree | 31 | 27 | 21 |

| Strongly disagree | 31 | 39 | 46 |

| Don't know | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| No opinion | - | - | 4 |

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Base | 3,100 | 3,160 | 3,090 |

10.2.3.2 The contribution of behaviour and everyday lifestyle to climate change

Respondents were then asked about their agreement or disagreement with the statement: “I don’t believe my behaviour and everyday lifestyle contribute to climate change”. Again, disagreement with this statement suggests a perception that there is a link between individual behaviours and lifestyle and climate change.

Table 10.3 shows that the proportion of adults who strongly disagree with this statement has increased by 13 percentage points between 2015 and 2018 (from 20 per cent to 33 per cent). Overall, in 2018, around six out of 10 adults disagreed with this statement and only two out of 10 agreed. Fewer adults stated that they either tend to disagree or tend to agree in 2018 compared to 2015, while the proportion of those who strongly agreed has stayed relatively consistent (six or seven per cent).

Table 10.3: “I don’t believe my behaviour and everyday lifestyle contribute to climate change”

Column percentages, 2015, 2017 and 2018 data

| Adults | 2015 | 2017 | 2018 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strongly agree | 6 | 6 | 7 |

| Tend to agree | 21 | 17 | 14 |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 15 | 13 | 13 |

| Tend to disagree | 34 | 33 | 25 |

| Strongly disagree | 20 | 26 | 33 |

| Don't know | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| No opinion | - | - | 3 |

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Base | 3,100 | 3,160 | 3,090 |

10.2.3.3 Perceptions about where climate change will have an impact

Respondents were invited next to agree or disagree with the following statement: “Climate change will only have an impact on other countries, there is no need for me to worry”. Disagreement with this statement suggests a perception that climate change will have an impact on Scotland, as well as on other countries.

Table 10.4 shows that, in 2018, more than three quarters of adults disagreed with this statement. As with other variables, there has been an increase in strong disagreement with this statement in every survey year (from 48 per cent in 2015 to 61 per cent in 2018) and a decrease in the proportion of adults who tended to disagree (from 28 to 17 per cent), which suggests a strengthening of opinion amongst those who disagreed. The overall proportion of adults who agreed with this statement (either tend to agree or strongly agree) has remained very low between 2015 and 2018 (six or seven per cent),

Table 10.4: “Climate change will only have an impact on other countries, there is no need for me to worry”

Column percentages, 2015, 2017 and 2018 data

| Adults | 2015 | 2017 | 2018 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strongly agree | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Tend to agree | 6 | 5 | 4 |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 10 | 9 | 8 |

| Tend to disagree | 28 | 24 | 17 |

| Strongly disagree | 48 | 54 | 61 |

| Don't know | 6 | 6 | 4 |

| No opinion | - | - | 4 |

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Base | 3,100 | 3,160 | 3,090 |

10.2.3.4 Understanding about actions that people can take to tackle climate change

Finally, respondents were invited to agree or disagree with the following statement: “I understand what actions people like myself should take to help tackle climate change”. Agreement with this statement suggests that respondents believe that they know what actions they could take personally, though it would not show whether they actually do know, or whether they are taking any action in practice.

Table 10.5 shows that, in 2018, around three quarters of adults agreed with this statement, with an increase in strong agreement consistently observed each survey year and a corresponding decrease in the proportion tending to agree. There was also a decrease in the proportion of adults who tended to disagree with this statement (from seven per cent to four per cent). Overall, between 2015 and 2018, the proportion of adults who either strongly disagreed or tended to disagree with this statement has remained low, at around one in 10.

Table 10.5: “I understand what actions people like myself should take to help tackle climate change”

Column percentages, 2015, 2017 and 2018 data

| Adults | 2015 | 2017 | 2018 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strongly agree | 26 | 31 | 34 |

| Tend to agree | 47 | 43 | 40 |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 13 | 11 | 11 |

| Tend to disagree | 7 | 7 | 4 |

| Strongly disagree | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Don't know | 5 | 5 | 4 |

| No opinion | - | - | 3 |

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Base | 3,100 | 3,160 | 3,090 |

A separate report containing further analysis of Scottish Government data on climate change attitudes and behaviours, including the 2018 Scottish Household Survey data, is expected to be published in early 2020.

10.3 Visits to the Outdoors, Greenspace

10.3.1 Introduction and Context

Spending time outdoors has been associated with numerous benefits, with urban green and open spaces having been shown to contribute to public health and wellbeing[109].

Responsibility for promoting visits to the outdoors is shared between Scottish Natural Heritage, other agencies such as Forestry and Land Scotland, local authorities and the National Park Authorities. Local authorities and National Park Authorities are also responsible for developing core path networks in their areas. People have a right of access to most land and inland water in Scotland, for walking, cycling and other non-motorised activities.

The updated National Performance Framework includes two National Indicators which aim to measure progress in this area. These are:

- 'Visits to the outdoors', and

- ‘Access to green and blue spaces’.

The second indicator was renamed from the previous National Performance Framework to reflect that access to blue spaces should also be included when considering the importance of accessibility to greenspace. Although the term “blue space” was not used in the 2018 SHS questionnaire, greenspace was defined to include canal path, riverside or beach and as such the indicator will continue to be based on responses to this question in the survey.

Scottish Planning Policy (SPP)[110] and National Planning Framework 3 (NPF3)[111] aim to significantly enhance green infrastructure networks, particularly in and around Scotland’s cities and towns. Green infrastructure should be an integral part of place making and this is reflected in our policy approach, as well as in development plans across the country.

The section starts by looking at key factors and characteristics associated with outdoor visits for leisure and recreation purposes. This is followed by an exploration of the access to greenspace for adults in the local neighbourhood.

10.3.2 Visits to the Outdoors

Outdoor visits for leisure and recreation include visits to both urban and countryside open spaces (for example, parks, woodland, farmland, paths and beaches) for a range of purposes (such as walking, running, cycling or kayaking). The associated National Indicator is measured by the proportion of adults making one or more visits to the outdoors per week.

Fifty-nine per cent of Scottish adults visited Scotland's outdoors at least once a week in 2018 compared to 52 per cent in 2017 (see Table 10.6). The 2018 figure is the highest percentage observed since the start of the time series in 2012. The annual increase of seven percentage points is also the largest observed. Less than a fifth of adults reported visiting the outdoors at least once a month while 11 per cent of adults reported that they did not visit the outdoors at all in 2018. In 2012, 20 per cent of adults reported not visiting the outdoors at all.

Table 10.6: Frequency of visits made to the outdoors

Column percentages, 2012-2018 data

| Adults | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| One or more times a week | 42 | 46 | 48 | 49 | 48 | 52 | 59 |

| At least once a month | 19 | 20 | 19 | 20 | 20 | 19 | 17 |

| At least once a year | 20 | 18 | 17 | 17 | 18 | 17 | 13 |

| Not at all | 20 | 16 | 16 | 14 | 13 | 12 | 11 |

| Base | 9,890 | 9,920 | 9,800 | 9,410 | 9,640 | 9,810 | 9,700 |

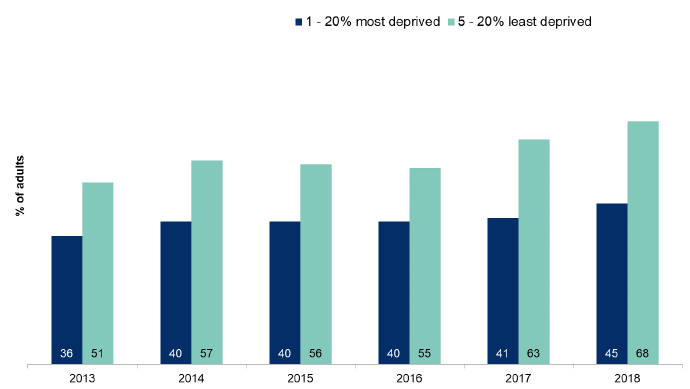

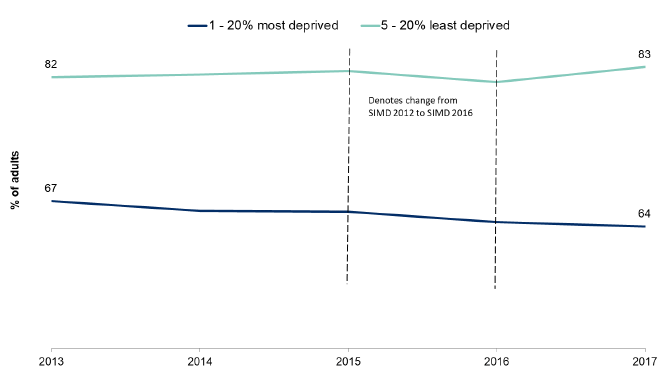

There is substantial variation in the proportion of adults making visits to the outdoors by level of area deprivation (Table 10.7). In the most deprived areas of Scotland, 45 per cent of adults visited the outdoors at least once a week, compared to 68 per cent of adults in the least deprived areas. Figure 10.4 further demonstrates that this difference has been consistently observed in previous years and that the increase over time has been greater in the least deprived areas. Adults in the most deprived areas were also more likely not to have visited the outdoors at all in the past 12 months (18 per cent) compared to those in the least deprived areas (five per cent).

Table 10.7: Frequency of visits made to the outdoors by Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation

Column percentages, 2018 data

| Adults | ← 20% most deprived | 20% least deprived → | Scotland | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| One or more times per week | 45 | 56 | 60 | 65 | 68 | 59 |

| At least once a month | 18 | 17 | 17 | 16 | 16 | 17 |

| At least once a year | 19 | 14 | 11 | 10 | 11 | 13 |

| Not at all | 18 | 13 | 12 | 9 | 5 | 11 |

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Base | 1,840 | 1,850 | 2,140 | 2,100 | 1,770 | 9,700 |

Figure 10.4: Percentage of adults visiting the outdoors at least once a week for 20% most and 20% least deprived areas

2013-2018 data, Adults (minimum base: 1,640)

Table 10.8 shows that in 2018 adults living in rural areas were more likely to visit the outdoors at least once a week compared to adults living in urban areas (69 per cent compared to 57 per cent). These figures are both increases from 2017 (61 per cent rural and 51 per cent urban).

Table 10.8: Frequency of visits made to the outdoors in the past 12 months by Urban/Rural classification

Column percentages, 2018 data

| Household | Urban | Rural | Scotland |

|---|---|---|---|

| Once or more times a week | 57 | 69 | 59 |

| At least once a month | 18 | 12 | 17 |

| At least once a year | 14 | 8 | 13 |

| Not at all | 11 | 11 | 11 |

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Base | 7,640 | 2,060 | 9,700 |

The proportion of men visiting the outdoors at least once a week in 2018 was the same as the proportion of women (59 per cent) (Table 10.9).

The age group with the highest proportion visiting the outdoors at least once a week was 25-34 year olds (66 per cent). Thirty per cent of the over 75 age group reported that they did not visit the outdoors at all in the past 12 months, which may reflect declining mobility and accessibility issues.

Table 10.9: Frequency of visits made to the outdoors in the past 12 months by gender and age group

Column percentages, 2018 data

| Adults | Men | Women | Identified in another way | Refused | 16-24 | 25-34 | 35-44 | 45-59 | 60-74 | 75+ | All |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| One or more times per week | 59 | 59 | * | * | 57 | 66 | 64 | 60 | 57 | 42 | 59 |

| At least once a month | 17 | 17 | * | * | 20 | 18 | 19 | 16 | 16 | 12 | 17 |

| At least once a year | 12 | 12 | * | * | 13 | 11 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 17 | 13 |

| Not at all | 11 | 11 | * | * | 10 | 5 | 5 | 10 | 14 | 30 | 11 |

| Total | 100 | 100 | * | * | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Base | 4,320 | 5,380 | 0 | 0 | 680 | 1,300 | 1,370 | 2,390 | 2,540 | 1,430 | 9,700 |

This is further reflected in the high proportion of those adults describing their health as either bad or very bad, who did not visit the outdoors at all in the last year (39 per cent). Conversely, 65 per cent of adults who described their health as good or very good reported that they visited the outdoors at least once a week (Table 10.10).

Table 10.10: Frequency of visits made to the outdoors in the past 12 months by self-perception of health

Column percentages, 2018 data

| Adults | Good / Very Good | Fair | Bad / Very Bad | Don't Know | All |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Once or more times a week | 65 | 48 | 28 | * | 59 |

| At least once a month | 17 | 18 | 15 | * | 17 |

| At least once a year | 11 | 18 | 19 | * | 13 |

| Not at all | 7 | 16 | 39 | * | 11 |

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | * | 100 |

| Base | 6,710 | 2,020 | 970 | 10 | 9,700 |

10.3.3 Walking Distance to Local Greenspace

Accessibility of greenspace is an important factor in its use, both in terms of its proximity to people's homes and the ease of physical access. The accessibility standard is taken to be equivalent to a five minute walk to the nearest publicly usable open space, which is the measurement used for the National Indicator. Greenspace is defined in the SHS as public green or open spaces in the local area such as parks, play areas, canal paths and beaches (private gardens are not included).

Respondents are asked how far the nearest greenspace is from their home and how long they think it would take the interviewer to walk there[112].

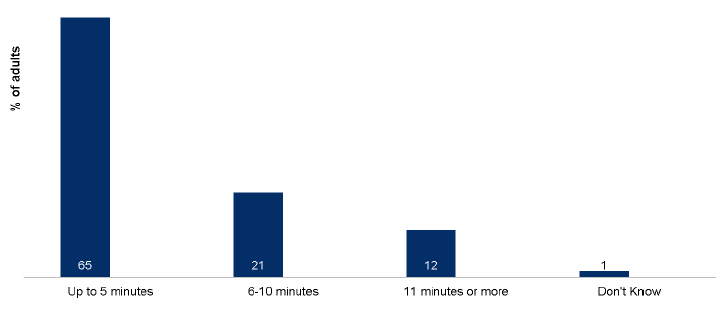

In 2018, 65 per cent of adults reported living within a five minute walk of their nearest greenspace (see Figure 10.5), unchanged from both 2017 and 2016. The earlier figures are 67 per cent in 2015, 69 per cent in 2014 and 68 per cent in 2013.

Figure 10.5: Percentage of adults within walking distance of nearest greenspace

2018 data. Random adults (base: 9,700)

10.3.4 Greenspace by level of area deprivation

People’s distance from their nearest greenspace varied with the level of area deprivation. Table 10.11 shows that a smaller proportion of adults in deprived areas lived within a five minute walk of their nearest greenspace compared to adults in the least deprived areas (58 per cent compared to 68 per cent).

Table 10.11: Walking distance to nearest greenspace by Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation

Column percentages, 2018 data

| Adults | ← 20a% most deprived | 20% least deprived → | Scotland | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| A 5 minute walk or less | 58 | 63 | 68 | 69 | 68 | 65 |

| Within a 6-10 minute walk | 26 | 22 | 20 | 17 | 22 | 21 |

| 11 minute walk or greater | 14 | 13 | 11 | 12 | 10 | 12 |

| Don't Know | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| All | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Base | 1,840 | 1,850 | 2,140 | 2,100 | 1,770 | 9,700 |

Satisfaction with greenspaces and how frequently they are used also varied with the level of area deprivation with the gap being consistent over time. Using previously published figures, Figure 10.6 shows that from 2013 to 2017 approximately two thirds of adults in the most deprived areas were satisfied with their nearest greenspace compared to four fifths of adults in the least deprived areas.

Figure 10.6: Percentage of adults expressing satisfaction with their nearest greenspace for 20% most and 20% least deprived areas

2013-2017 data. Random adults (minimum base: 1,630)

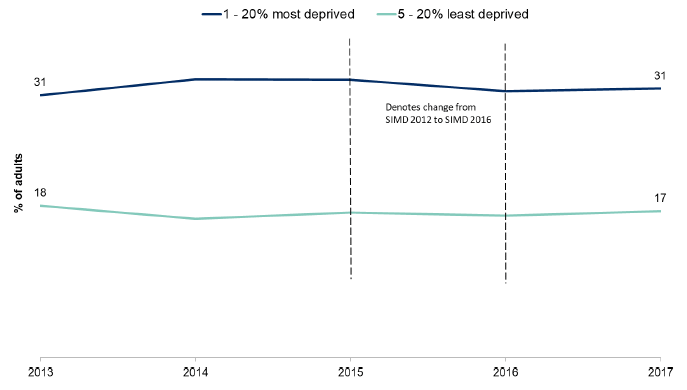

Figure 10.7 further shows that from 2013 to 2017 just under one third of adults in the most deprived areas did not use their nearest greenspace in the previous 12 months compared to approximately one sixth of adults in the least deprived areas.

Figure 10.7: Percentage of adults who have not visited their nearest greenspace in the previous 12 months for 20% most and 20% least deprived areas

2013-2017 data. Random adults (minimum base: 1,630)

The previously published 2017 annual report provides a detailed breakdown by area deprivation of adults’ satisfaction with their nearest greenspace[113] and how frequently they used it[114]. Similar breakdowns for earlier years are provided in the corresponding annual reports[115]. The next update to these figures will be for 2019 and published in 2020.

10.4 Participation in Land Use Decisions

The Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2016 recognises the importance of land in realising people’s human rights. This is reflected in the principles of the Scottish Land Rights and Responsibilities Statement[116]. In particular, Principle 4 states that:

“The holders of land rights should exercise these rights in ways that take account of their responsibilities to meet high standards of land ownership, management and use. Acting as the stewards of Scotland's land resource for future generations they contribute to sustainable growth and a modern, successful country.”

Principle 6 further states:

“There should be greater collaboration and community engagement in decisions about land.”

This recognises that participation in land use decisions is important in giving communities more control over the land where they live and work. In April 2018 the Scottish Government published its Guidance on Engaging Communities in Decisions Relating to Land[117], which sets out the responsibilities of those with control over land, both owners and tenants, in terms of engaging with communities about decisions relating to land.

10.4.1 Participation in land use decisions

SHS 2018 gave a list of possible ways people could have used to give their views on land use decisions, which are given in Table 10.12. In 2018, 15 per cent of adults reported that they gave their views on land use in at least one of these ways, the same proportion as in 2015 and 2017.

The most common way in which people reported giving their views on land use was by signing a petition (seven per cent of adults) and the least common was through discussions with a land owner or land manager (one per cent of adults). This may be because signing a petition does not require much effort and is more likely to be about an issue affecting a larger number of people. Having a discussion with a land owner or manager, on the other hand, requires more time and effort and is more likely to be about an issue affecting fewer individuals in that specific area (smaller area issues).

Table 10.12: Percentage of people who gave their views on land use in the last 12 months[118]

Column percentages, 2015, 2017 and 2018 data

| Adults | 2015 | 2017 | 2018 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Signed a petition | 7 | 7 | 7 |

| Attended a public meeting/ community council meeting | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Took part in a consultation or a survey | 5 | 5 | 6 |

| Responded to a planning application | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Been involved with interest group or campaign | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Contacted an MP, MSP or Local Councillor | 4 | 3 | 3 |

| Had discussions with a landowner/land-manager | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| None of the above | 85 | 85 | 85 |

| Base | 9,410 | 9,810 | 9,700 |

As shown in Table 10.13, a greater proportion of adults living in rural areas reported giving their views on land use compared to adults living in urban areas (20 per cent compared to 14 per cent). The proportions in 2018 are very similar to 2017 and 2015.

Table 10.13: Percentage of people who gave their views on land use by Urban/Rural classification[119]

Column percentages, 2015, 2017 and 2018 data

| Adults | Urban | Rural | Scotland |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 14 | 21 | 15 |

| Base | 7,420 | 1,980 | 9,410 |

| 2017 | 14 | 20 | 15 |

| Base | 7,790 | 2,020 | 9,810 |

| 2018 | 14 | 20 | 15 |

| Base | 7,640 | 2,060 | 9,700 |

Contact

Email: shs@gov.scot

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback