Scottish household survey 2018: annual report

Results from the 2018 edition of the continuous survey based on a sample of the general population in private residences in Scotland.

4 Neighbourhoods and Communities

Main Findings

The majority of adults in Scotland (57.4 per cent) rated their neighbourhood as a very good place to live. This has improved by 4.3 percentage points over the last 10 years. Over nine in 10 adults rated their neighbourhood as a very or fairly good place to live in 2018.

Neighbourhood ratings varied by area deprivation. Adults in less deprived areas were more likely to rate their neighbourhood as a very good place to live. However, the proportion of people living in the 20 per cent most deprived areas who rated their neighbourhood as very good has increased over the last decade, and the gap between the most and least deprived areas has slightly narrowed since 2006.

Those in accessible or remote rural areas were more likely to describe their neighbourhood as a very good place to live than those in urban areas.

People were positive about different aspects of their neighbourhoods but were more positive about the people-based factors (such as kindness, trust and people taking action to improve the neighbourhood) and less positive about the physical aspects of their neighbourhoods (such as the availability of places to meet new people, and socialise).

Over three-quarters (78 per cent) of adults felt a very or fairly strong sense of belonging to their neighbourhood in 2018. This varied according to age, ethnic group and deprivation where sense of belonging was lower for younger people, ethnic minorities and people living in deprived areas.

More than three-quarters of adults agreed with all statements regarding neighbourhood involvement (such as level of neighbourhood support, and reliance on friends/neighbours). The majority of adults in Scotland strongly agreed that they would assist neighbours in an emergency (91 per cent) and could rely on those around them for advice and support (77 per cent).

The majority of adults in Scotland (73 per cent) met socially with friends, relatives, neighbours or work colleagues at least once a week. One in five adults living in Scotland experienced feelings of loneliness in the last week, and this didn’t vary by the respondents’ age. Although level of deprivation did not impact social isolation, as measured by the number of people meeting socially at least once a week, those living in the most deprived areas were almost twice as likely to experience feelings of loneliness as those living in the least deprived areas. People living with a long-term physical or mental health condition were more than twice as likely to experience loneliness as those without.

Forty-six per cent of all adults reported that they did not experience any neighbourhood problems in 2018. Those living in the 20 per cent most deprived areas were more likely to experience neighbourhood problems.

The most prevalent perceived neighbourhood problems were rubbish or litter lying around and animal nuisance (both 30 per cent).

One in 12 adults reported that they had experienced discrimination and one in 17 had experienced harassment in the last 12 months. Some groups were more likely than others to report having experienced discrimination or harassment in Scotland, for instance ethnic minorities, people who are gay/lesbian/bisexual and those who reported belonging to a religion other than Christianity. The most common reason cited as a motivating factor was the respondent’s nationality.

The majority of households in Scotland (64 per cent) reported that they have not thought about, or made any preparations for, events like severe weather or flooding.

4.1 Introduction and Context

The National Performance Framework in Scotland contains a vision for our communities to be inclusive, empowered, resilient and safe.

Data from the Scottish Household Survey (SHS) is a helpful means for us to understand progress towards achieving this outcome. This chapter presents the latest findings from the survey relevant to our neighbourhoods and communities.

This chapter also includes four national indicators[54]:

- Perceptions of local area

- Loneliness

- Places to interact

- Social capital (which is a dashboard measure but based on some of the variables discussed in this chapter).

The chapter starts with an overview of the latest results on people’s perceptions of their local area and its strengths, including statistical breakdowns by demographic and geographic characteristics. It then goes on to investigate how engaged people were with their local community. This section has been updated to include new variables measuring social isolation and feelings of loneliness.

Perceptions and experiences of various forms of neighbourhood problems such as anti-social behaviour are then explored, before looking at experiences of discrimination and harassment. Finally, it investigates how prepared households were for emergency situations in 2018.

4.2 Neighbourhoods

The section below explores how people viewed their neighbourhoods and their impression of how their local area has changed (if at all) over the last few years.

4.2.1 Overall Ratings of Neighbourhoods

The majority of adults in Scotland (57.4 per cent) rated their neighbourhood as a very good place to live in 2018 - an indicator in the National Performance Framework - as shown in Table 4.1. When ‘very good’ and ‘fairly good’ is added together, 94.6 per cent of adults felt positively about their neighbourhood.

Ratings of neighbourhoods have been consistently high since the SHS began in 1999, with over nine in 10 adults viewing their neighbourhood as a very or fairly good place to live in each year. The number of people rating their neighbourhood as very/fairly good in 2018 has significantly increased from 2008.

Table 4.1: Rating of neighbourhood as a place to live by year

Column percentages, 1999; 2008-2018 data

| Adults | 1999 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Very/fairly good | 90.7 | 92.5 | 93.6 | 93.5 | 93.9 | 93.7 | 94.1 | 94.4 | 94.6 | 95.0 | 95.0 | 94.6 |

| Very good | 49.4 | 53.1 | 55.0 | 55.4 | 55.9 | 55.2 | 55.2 | 55.8 | 56.3 | 56.7 | 57.0 | 57.4 |

| Fairly good | 41.3 | 39.4 | 38.6 | 38.1 | 38.0 | 38.5 | 38.9 | 38.5 | 38.3 | 38.3 | 38.0 | 37.2 |

| Fairly poor | 5.4 | 4.9 | 4.3 | 4.4 | 4.2 | 4.3 | 4.1 | 3.6 | 3.7 | 3.6 | 3.4 | 4.0 |

| Very poor | 3.4 | 2.4 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 1.5 | 1.7 | 1.4 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 1.2 |

| No opinion | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Base | 13,780 | 9,310 | 12,540 | 12,440 | 12,890 | 9,890 | 9,920 | 9,800 | 9,410 | 9,640 | 9,810 | 9,700 |

Whilst neighbourhoods were rated positively across the board, ratings varied by urban rural classification (Table 4.2). Those in accessible or remote rural areas were most likely to describe their neighbourhood as a very good place to live (69 per cent and 77 per cent respectively).

Table 4.2: Rating of neighbourhood as a place to live by Urban Rural classification

Column percentages, 2018 data

| Adults | Large urban areas | Other urban areas | Accessible small towns | Remote small towns | Accessible rural | Remote rural | Scotland |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Very/fairly good | 93 | 94 | 95 | 96 | 97 | 98 | 95 |

| Very good | 53 | 54 | 60 | 60 | 69 | 77 | 57 |

| Fairly good | 41 | 40 | 36 | 36 | 28 | 21 | 37 |

| Fairly poor | 5 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 4 |

| Very poor | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| No opinion | 0 | 0 | 0 | - | - | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Base | 2,970 | 3,250 | 840 | 580 | 1,030 | 1,030 | 9,700 |

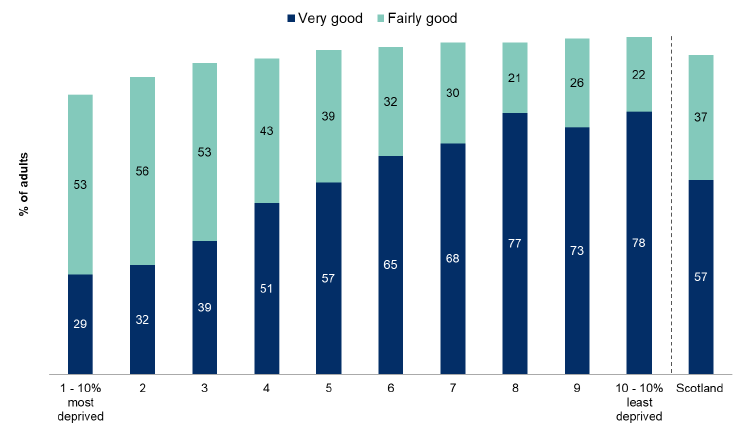

Neighbourhood ratings also varied by deprivation[55], with the proportion of adults rating their neighbourhood as a very good place to live increasing as deprivation decreases, as shown in Figure 4.1.

Just under three in 10 adults in the 10 per cent most deprived areas of Scotland rated their neighbourhood as a very good place to live in 2018, compared to almost eight in 10 of those living in the 10 per cent least deprived areas. Overall, more than four-fifths (82 per cent) of adults in the most deprived areas described their neighbourhood as either very or fairly good.

Figure 4.1: Rating of neighbourhood as a place to live by Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation

2018 data, Adults (minimum base: 860)

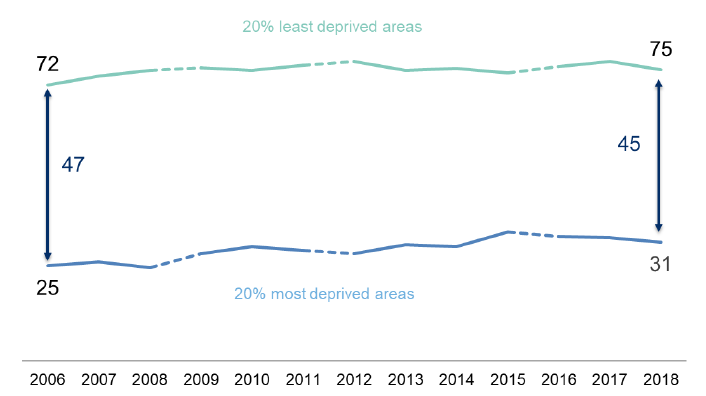

Neighbourhood ratings have improved amongst those living in the most deprived areas over the last decade (Figure 4.2). For those who live in the 20 per cent most deprived areas, the proportion rating their neighbourhood as a very good place to live has increased from 25 per cent in 2006 to 31 per cent in 2018.

Notwithstanding some year-to-year fluctuations, the gap between the 20 per cent most and least deprived areas has narrowed slightly since 2006 when we look at those describing their neighbourhood as a very good place to live.

Figure 4.2: Rating of neighbourhood as a very good place to live by Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation 20 per cent and 20 per cent least deprived areas

2006-2018 data, Adults (minimum base: 1,580)

Note: Dotted lines represent breaks in SIMD data. Calculation based on unrounded data.

4.2.2 Neighbourhood Strengths

For 2018, an updated set of questions were included in the SHS to explore how the population perceives their neighbourhood strengths.

The survey asked people about their experiences and perceptions of trust, kindness, welcome, social contact, help and getting on well with people from different backgrounds.

The percentage of people agreeing with statements about their neighbourhood strengths is higher for people-based strengths (such as kindness, trust and people from different backgrounds getting on well together) and lower for place-based strengths (such as welcoming places and places where people can meet up and socialise). Eighty-three per cent[56] of adults living in Scotland believed their neighbourhood is one where people are kind to each other, and 78 per cent believed their neighbourhood is one where people can be trusted. In contrast, just over half of people living in Scotland (53 per cent[57]) believed that there are welcoming places and opportunities to meet new people in their neighbourhood, and 59 per cent agreed that there are places where people can meet up and socialise – an indicator in the National Performance Framework.

Table 4.3 shows that adults are also more likely to strongly disagree with statements about place-based strengths compared to people-based strengths. Around one in 10 people strongly disagreed that their neighbourhood has welcoming places and opportunities to meet new people (nine per cent), and that their neighbourhood has places where people can meet up and socialise (10 per cent).

Table 4.3 Percentage of people agreeing with statements about their neighbourhood strengths

Column percentages, 2018 data

| Adults | Strongly agree | Tend to agree | Neither agree nor disagree | Tend to disagree | Strongly disagree | Don't know | Base |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| This is a neighbourhood where people are kind to each other | 40 | 42 | 12 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 9700 |

| This is a neighbourhood where most people can be trusted | 38 | 40 | 13 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 9700 |

| There are welcoming places and opportunities to meet new people | 19 | 33 | 16 | 18 | 9 | 4 | 9700 |

| There are places where people can meet up and socialise | 22 | 37 | 12 | 16 | 10 | 3 | 9700 |

| This is a neighbourhood where people from different backgrounds get on well together | 25 | 45 | 18 | 4 | 2 | 6 | 9700 |

| This is a neighbourhood where local people take action to help improve the neighbourhood | 23 | 35 | 21 | 10 | 4 | 7 | 9700 |

Perception of neighbourhood strengths generally improves with age (Table 4.4). In particular, neighbourhood kindness, neighbourhood trust and people taking action to help improve the local area were perceived to be lower amongst younger people compared to older people.

Table 4.4: Percentage of people agreeing with statements about their neighbourhood strengths by age

Column percentages, 2018 data

| Adults | Age | Scotland | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16-24 | 25-34 | 35-44 | 45-59 | 60-74 | 75+ | ||

| This is a neighbourhood where people are kind to each other | 79 | 78 | 84 | 83 | 85 | 87 | 83 |

| This is a neighbourhood where most people can be trusted | 69 | 69 | 75 | 79 | 85 | 87 | 78 |

| There are welcoming places and opportunities to meet new people | 52 | 53 | 53 | 50 | 54 | 55 | 53 |

| There are places where people can meet up and socialise | 57 | 58 | 58 | 59 | 61 | 60 | 59 |

| This is a neighbourhood where people from different backgrounds get on well together | 68 | 67 | 68 | 72 | 74 | 71 | 70 |

| This is a neighbourhood where local people take action to help improve the neighbourhood | 44 | 52 | 60 | 61 | 63 | 62 | 58 |

| Base | 680 | 1300 | 1370 | 2390 | 2540 | 1430 | 9700 |

A higher proportion of people living in accessible and remote rural areas agreed with statements regarding neighbourhood strengths than people living in large and other urban areas (Table 4.5). Almost three-quarters (73 per cent) of adults living in remote rural areas agreed that people take action to improve their neighbourhood, compared to just over half (51 per cent) of those living in other urban areas.

Table 4.5: Percentage of people agreeing with statements about their neighbourhood strengths by Urban Rural Classification

Column percentages, 2018 data

| Adults | Urban-Rural Classification | Scotland | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Large urban areas | Other urban areas | Accessible small towns | Remote small towns | Accessible rural | Remote rural | ||

| This is a neighbourhood where people are kind to each other | 79 | 81 | 86 | 80 | 90 | 89 | 83 |

| This is a neighbourhood where most people can be trusted | 73 | 75 | 83 | 77 | 88 | 89 | 78 |

| There are welcoming places and opportunities to meet new people | 55 | 46 | 59 | 56 | 57 | 63 | 53 |

| There are places where people can meet up and socialise | 62 | 51 | 67 | 61 | 62 | 66 | 59 |

| This is a neighbourhood where people from different backgrounds get on well together | 71 | 67 | 73 | 70 | 75 | 75 | 70 |

| This is a neighbourhood where local people take action to help improve the neighbourhood | 55 | 51 | 66 | 55 | 72 | 73 | 58 |

| Base | 2970 | 3250 | 840 | 580 | 1030 | 1030 | 9700 |

Owner occupiers are more likely to agree with the statements regarding neighbourhood people-based strengths than people who rent their home (Table 4.6). Eighty-five per cent of owner occupied households regarded their neighbourhood as one where most people can be trusted compared to 61 per cent of socially rented households.

Table 4.6: Percentage of people agreeing with statements about their neighbourhood strengths by tenure

Column percentages, 2018 data

| Adults | Tenure | Scotland | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Owner occupied | Social rented | Private rented | Other | ||

| This is a neighbourhood where people are kind to each other | 87 | 74 | 74 | 81 | 83 |

| This is a neighbourhood where most people can be trusted | 85 | 61 | 65 | 77 | 78 |

| There are welcoming places and opportunities to meet new people | 54 | 45 | 59 | 51 | 53 |

| There are places where people can meet up and socialise | 61 | 50 | 64 | 58 | 59 |

| This is a neighbourhood where people from different backgrounds get on well together | 73 | 63 | 67 | 64 | 70 |

| This is a neighbourhood where local people take action to help improve the neighbourhood | 64 | 47 | 46 | 54 | 58 |

| Base | 6190 | 2250 | 1160 | 110 | 9700 |

4.3 Community Engagement

4.3.1 Neighbourhood Belonging

The SHS also seeks to explore how strongly adults feel that they belong to their immediate neighbourhood. Table 4.7 shows that 78 per cent of adults felt a very or fairly strong sense of belonging to their neighbourhood in 2018, a finding which has been stable in recent years.

Whilst the majority of all adults said that they felt a very strong or fairly strong sense of belonging, there is variation between breakdown groups. Table 4.7 shows that the age, ethnicity and area respondents lived in affected their strength of feeling of belonging. The gender of the respondent had no bearing on their strength of belonging.

Almost nine in 10 adults (87 per cent) aged 75 and above said they felt a very strong or fairly strong sense of belonging to their community, compared to two thirds (67 per cent) of those aged 25-34.

Seventy-eight per cent of those whose ethnicity was recorded as White expressed a very or fairly strong feeling of belonging compared to 71 per cent of those whose ethnicity was recorded as minority ethnic[58].

Those who live in the 20 per cent most deprived areas were less likely to have a strong feeling of belonging to the community compared to those in the 20 per cent least deprived areas (71 per cent and 83 per cent[59] respectively).

Table 4.7: Strength of feeling of belonging to community by gender, age, ethnicity and Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation

Row percentages, 2018 data

| Adults | Very strongly | Fairly strongly | Not very strongly | Not at all strongly | Don't know | Total | Base |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||||||

| Men | 34 | 42 | 17 | 5 | 1 | 100 | 4,320 |

| Women | 38 | 42 | 15 | 4 | 1 | 100 | 5,380 |

| Identified in another way | * | * | * | * | * | * | 0 |

| Refused | * | * | * | * | * | * | 0 |

| Age | |||||||

| 16-24 | 28 | 45 | 19 | 7 | 2 | 100 | 680 |

| 25-34 | 24 | 43 | 23 | 7 | 2 | 100 | 1,300 |

| 35-44 | 30 | 46 | 18 | 5 | 2 | 100 | 1,370 |

| 45-59 | 37 | 42 | 16 | 4 | 1 | 100 | 2,390 |

| 60-74 | 45 | 41 | 11 | 2 | 1 | 100 | 2,540 |

| 75+ | 56 | 31 | 9 | 2 | 1 | 100 | 1,430 |

| Ethnicity | |||||||

| White | 37 | 42 | 16 | 5 | 1 | 100 | 9,410 |

| Minority Ethnic Groups | 25 | 47 | 21 | 4 | 4 | 100 | 290 |

| Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation | |||||||

| 20% Most Deprived Areas | 31 | 40 | 19 | 8 | 1 | 100 | 1,840 |

| 20% Least Deprived Areas | 37 | 45 | 14 | 2 | 1 | 100 | 1,770 |

| All | 36 | 42 | 16 | 5 | 1 | 100 | 9,700 |

4.3.2 Neighbourhood Involvement

Along with feelings of neighbourhood belonging, the SHS explored neighbourhood involvement. This included perceptions about social support and social connections within neighbourhoods.

Table 4.8 highlights that over three-quarters of adults in Scotland agreed with all statements regarding their neighbourhood involvement. Offering help to a neighbour in an emergency had the highest level of agreement (91 per cent) whilst turning to someone in the neighbourhood for advice or support had the lowest level of agreement (77 per cent). Neighbourhood involvement was generally higher for older people, those living in remote rural areas, and those living in less deprived areas.

Table 4.8: Involvement with other people in the neighbourhood by gender, age, ethnicity and SIMD

Column percentages, 2018 data

| Adults | Age | Gender | Scotland | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16-24 | 25-34 | 35-44 | 45-59 | 60-74 | 75+ | Men | Women | Identified in another way | Refused | ||

| Could rely on someone in neighbourhood for help | 81 | 79 | 85 | 87 | 89 | 93 | 84 | 87 | * | * | 86 |

| Could rely on someone in neighbourhood to look after home | 78 | 77 | 85 | 88 | 90 | 94 | 84 | 87 | * | * | 85 |

| Could turn to someone in neighbourhood for advice or support | 72 | 68 | 77 | 78 | 83 | 86 | 75 | 79 | * | * | 77 |

| Would offer help to neighbours in an emergency | 89 | 90 | 92 | 93 | 92 | 83 | 91 | 90 | * | * | 91 |

| Base | 680 | 1300 | 1370 | 2390 | 2540 | 1430 | 4320 | 5380 | 0 | 0 | 9700 |

| Adults | Urban-Rural Classification | 20% most deprived | 20% least deprived | Scotland | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Large urban areas | Other urban areas | Accessible small towns | Remote small towns | Accessible rural | Remote rural | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| Could rely on someone in neighbourhood for help | 83 | 85 | 90 | 85 | 89 | 93 | 80 | 83 | 88 | 87 | 90 | 86 |

| Could rely on someone in neighbourhood to look after home | 81 | 85 | 91 | 89 | 92 | 93 | 79 | 82 | 86 | 89 | 90 | 85 |

| Could turn to someone in neighbourhood for advice or support | 75 | 75 | 80 | 76 | 84 | 86 | 72 | 74 | 78 | 80 | 80 | 77 |

| Would offer help to neighbours in an emergency | 91 | 89 | 90 | 91 | 93 | 93 | 86 | 89 | 91 | 93 | 94 | 91 |

| Base | 2970 | 3250 | 840 | 580 | 1030 | 1030 | 1840 | 1850 | 2140 | 2100 | 1770 | 9700 |

4.3.3 Social Isolation and Loneliness

For 2018, an updated set of questions were included in the SHS to explore feelings of loneliness and isolation in Scotland. Loneliness is an indicator in the National Performance Framework.

Social isolation refers to when an individual has an objective lack of social relationships (in terms of quality and/or quantity) at individual, group, community and societal levels. Loneliness is a subjective feeling experienced when there is a difference between the social relationships we would like to have and those we have[60].

Table 4.9 shows that the majority of adults in Scotland (73 per cent) reported meeting socially with friends, family, relatives, neighbours or work colleagues at least once a week. Middle-aged people (35-59) were less likely to meet socially at least once a week than other ages (65 and 66 per cent for people in this age category, compared to 86 per cent of people aged 16-24). Women met socially more regularly than men.

Table 4.9: Social isolation: how often people meet socially with friends, relatives, neighbours or work colleagues by age and gender

Column percentages, 2018 data

| Adults | Age | Gender | Scotland | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16-24 | 25-34 | 35-44 | 45-59 | 60-74 | 75+ | Men | Women | Identified in another way | Refused | ||

| At least once a week | 86 | 74 | 65 | 66 | 75 | 77 | 70 | 75 | * | * | 73 |

| At least once a month | 11 | 20 | 24 | 23 | 16 | 13 | 20 | 18 | * | * | 19 |

| A few times a year/very rarely | 3 | 4 | 9 | 9 | 7 | 7 | 8 | 6 | * | * | 7 |

| Never | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | * | * | 1 |

| Don’t know | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | * | * | 0 |

| All | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | * | * | 100 |

| Base | 680 | 1300 | 1370 | 2390 | 2540 | 1430 | 4320 | 5380 | 0 | 0 | 9700 |

Table 4.10 shows that there is no obvious trend in meeting socially at least once a week between urban and rural areas or by area deprivation levels.

Table 4.10: Social isolation: how often people meet socially with friends, relatives, neighbours or work colleagues by Urban-Rural Classification and SIMD

Column percentages, 2018 data

| Adults | Urban-Rural Classification | ← 20% most deprived | 20% least deprived → | Scotland | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Large urban areas | Other urban areas | Accessible small towns | Remote small towns | Accessible rural | Remote rural | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| At least once a week | 75 | 72 | 68 | 77 | 70 | 72 | 72 | 73 | 71 | 72 | 74 | 73 |

| At least once a month | 18 | 19 | 21 | 14 | 20 | 17 | 18 | 16 | 20 | 20 | 19 | 19 |

| A few times a year/very rarely | 5 | 7 | 9 | 6 | 8 | 9 | 7 | 8 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 7 |

| Never | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Don’t know | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| All | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Base | 2970 | 3250 | 840 | 580 | 1030 | 1030 | 1840 | 1850 | 2140 | 2100 | 1770 | 9700 |

Table 4.11 shows that people living with a long-term physical or mental health condition were less likely to meet socially more often than people living without this. Sixty-nine per cent of people with a long-term physical or mental health condition met socially at least once a week compared to 74 per cent of people without.

Table 4.11: How often people meet socially with friends, relatives, neighbours or work colleagues by long-term physical or mental health condition status

Column percentages, 2018 data

| Adults | Long-term physical or mental health condition | Scotland | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Don't know | Refused | ||

| At least once a week | 69 | 74 | * | * | 73 |

| At least once a month | 18 | 19 | * | * | 19 |

| A few times a year/very rarely | 9 | 6 | * | * | 7 |

| Never | 3 | 1 | * | * | 1 |

| Don’t know | 0 | 0 | * | * | 0 |

| All | 100 | 100 | * | * | 100 |

| Base | 3330 | 6330 | 20 | 20 | 9700 |

Loneliness

Whilst the majority of adults in Scotland reported having no or almost no feelings of loneliness in the last week, one in five adults (21 per cent) did feel lonely some or most of the time. Table 4.12 highlights that feelings of loneliness were similar across all age categories.

Table 4.12: How often people have felt lonely within the last week by age

Column percentages, 2018 data

| Adults | Age | Scotland | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16-24 | 25-34 | 35-44 | 45-59 | 60-74 | 75+ | ||

| None or almost none of the time | 76 | 75 | 80 | 79 | 82 | 74 | 78 |

| Some of the time | 20 | 20 | 16 | 16 | 15 | 21 | 17 |

| Most, almost all, or all of the time | 3 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 4 |

| Don’t know | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| All | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Base | 680 | 1300 | 1370 | 2390 | 2540 | 1430 | 9700 |

Although level of deprivation did not impact social isolation, as measured by the number of people meeting socially at least once a week, those living in the most deprived areas were almost twice as likely to experience feelings of loneliness as those living in the least deprived areas (Table 4.13). Twenty-eight per cent of people living in the most deprived areas experienced feelings of loneliness in the last week, compared to 15 per cent[61] of people living in the least deprived areas.

Table 4.13: How often people have felt lonely within the last week by Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation

Column percentages, 2018 data

| Adults | ← 20% most deprived | 20% least deprived→ | Scotland | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| None or almost none of the time | 71 | 76 | 77 | 82 | 84 | 78 |

| Some of the time | 21 | 19 | 18 | 15 | 14 | 17 |

| Most, almost all, or all of the time | 7 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Don’t know | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| All | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Base | 1840 | 1850 | 2140 | 2100 | 1770 | 9700 |

There is also some variance in feelings of loneliness by urban rural classification. Table 4.14 shows that remote small towns had the highest prevalence of loneliness (26 per cent compared to 15 per cent[62] for those living in accessible rural areas).

Table 4.14: How often people have felt lonely within the last week by Urban Rural Classification

Column percentages, 2018 data

| Adults | Urban-Rural Classification | Scotland | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Large urban areas | Other urban areas | Accessible small towns | Remote small towns | Accessible rural | Remote rural | ||

| None or almost none of the time | 78 | 76 | 78 | 74 | 84 | 80 | 78 |

| Some of the time | 17 | 19 | 18 | 21 | 13 | 17 | 17 |

| Most, almost all, or all of the time | 4 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 4 |

| Don’t know | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| All | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Base | 2970 | 3250 | 840 | 580 | 1030 | 1030 | 9700 |

Table 4.15 shows that people living with a long-term physical or mental health condition are more than twice as likely to experience feelings of loneliness within the last week compared to those without (34 per cent vs 16 per cent[63]).

Table 4.15: How often people have felt lonely within the last week by long-term physical or mental health condition status

Column percentages, 2018 data

| Adults | Long-term physical or mental health condition | Scotland | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Don't know | Refused | ||

| None or almost none of the time | 65 | 84 | * | * | 78 |

| Some of the time | 26 | 14 | * | * | 17 |

| Most, almost all, or all of the time | 9 | 2 | * | * | 4 |

| Don't know | 1 | 1 | * | * | 1 |

| All | 100 | 100 | * | * | 100 |

| Base | 3330 | 6330 | 20 | 20 | 9700 |

Chapter 2 shows that over a third of people in Scotland lived alone, and Table 4.16 shows that feelings of loneliness were highest in single-occupier households in 2018. Forty per cent of people living in single adult households and 38 per cent[64] of people living in single pensioner households experienced feelings of loneliness in the last week. Over a third (34 per cent) of respondents in single parent households experienced feelings of loneliness in the last week.

Table 4.16: How often people have felt lonely within the last week by household type

Column percentages, 2018 data

| Adults | Household Type | Scotland | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single adult | Small adult | Single parent | Small family | Large family | Large adult | Older smaller | Single pensioner | ||

| None or almost none of the time | 59 | 80 | 66 | 85 | 86 | 83 | 88 | 62 | 78 |

| Some of the time | 29 | 17 | 26 | 14 | 11 | 13 | 10 | 29 | 17 |

| Most, almost all, or all of the time | 11 | 2 | 9 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 8 | 4 |

| Don’t know | 1 | 1 | - | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| All | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Base | 2080 | 1690 | 470 | 1090 | 450 | 700 | 1570 | 1650 | 9700 |

4.4 Neighbourhood Problems

4.4.1 Perceptions of Neighbourhood Problems

As well as asking respondents about their general views on their neighbourhoods, the SHS also collects information on perceptions and experiences of specific neighbourhood problems, such as anti-social behaviour. As with previous years, the nine neighbourhood problems which respondents were asked about are categorised in four key groups as shown below.

General anti-social behaviour

Vandalism / graffiti / damage to property

Groups or individuals harassing others

Drug misuse or dealing

Rowdy behaviour

Neighbour problems

Noisy neighbours/ loud parties

Neighbour disputes

Rubbish and fouling

Rubbish or litter lying around

Animal nuisance such as noise or dog fouling

Vehicles

Abandoned or burnt out vehicles

Perceptions of social problems are outlined in Table 4.17 which shows the percentage of adults describing each issue as very or fairly common in their neighbourhood over the last 10 years.

Continuing the trend seen over the last decade, the most prevalent issues cited in 2018 were:

- Animal nuisance such as noise or dog fouling (which 30 per cent saw as very or fairly common); and

- Rubbish or litter lying around (which 30 per cent said was very or fairly common).

Notwithstanding relatively minor (although sometimes statistically significant) fluctuations in the estimated proportion of adults viewing each issue as common between survey sweeps, many perceived problems have been broadly stable in recent years. Looking over the longer term reveals more notable changes in some categories. For instance, the proportion of people citing vandalism/damage to property as a common issue almost halved between 2008 and 2018, whilst the perceived commonality of animal nuisance has increased since 2009.

Table 4.17: Percentage of people saying a problem is very/fairly common in their neighbourhood

Percentages, 2008-2018 data

| Adults | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General anti-social behaviour | ||||||||||||

| Vandalism / graffiti / damage to property | 17 | 15 | 14 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 10 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 9 | 8 |

| Groups or individual harassing others | 12 | 11 | 10 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| Drug misuse or dealing | 12 | 13 | 12 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 12 | 11 | 12 | 12 | 13 | 12 |

| Rowdy behaviour | 17 | 17 | 16 | 14 | 14 | 15 | 13 | 12 | 11 | 11 | 12 | 11 |

| Neighbour problems | ||||||||||||

| Noisy neighbours / loud parties | 9 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 12 | 11 | 11 | 10 | 10 | 11 | 10 |

| Neighbour disputes | 5 | 5 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| Rubbish and fouling | ||||||||||||

| Rubbish or litter lying around | 29 | 29 | 26 | 24 | 25 | 29 | 27 | 27 | 28 | 30 | 30 | 30 |

| Animal nuisance such as noise or dog fouling | - | - | 24 | 23 | 26 | 30 | 31 | 31 | 31 | 31 | 32 | 30 |

| Vehicles | ||||||||||||

| Abandoned or burnt out vehicles | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Base | 10,390 | 9,310 | 11,400 | 11,140 | 11,280 | 9,890 | 9,920 | 9,800 | 9,410 | 9,640 | 9,810 | 9,700 |

Columns may not add to 100 per cent since multiple responses were allowed.

4.4.2 Variation in Neighbourhood Problems

The perceived prevalence of neighbourhood problems varied by deprivation. Table 4.18 shows that those living in the most deprived areas were more likely to perceive each issue to be a very or fairly common problem compared to those who lived in the least deprived areas. The most notable differences being the commonality of rubbish or litter lying around (48 per cent compared to 20 per cent) and drug misuse or dealing (30 per cent compared to two per cent).

Table 4.18: Percentage of people saying a problem is very/fairly common in their neighbourhood by Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation

Percentages, 2018 data

| Adults | 10% most deprived | 10% least deprived | Scotland | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | ||

| General anti-social behaviour | |||||||||||

| Vandalism / graffiti / damage to property | 20 | 16 | 10 | 9 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 8 |

| Groups or individual harassing others | 15 | 12 | 8 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 6 |

| Drug misuse or dealing | 30 | 27 | 19 | 15 | 11 | 8 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 12 |

| Rowdy behaviour | 25 | 20 | 16 | 14 | 10 | 8 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 11 |

| Neighbour problems | |||||||||||

| Noisy neighbours / loud parties | 20 | 18 | 14 | 12 | 10 | 6 | 7 | 6 | 4 | 5 | 10 |

| Neighbour disputes | 13 | 13 | 8 | 8 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 6 |

| Rubbish and fouling | |||||||||||

| Rubbish or litter lying around | 48 | 45 | 39 | 35 | 29 | 26 | 23 | 20 | 17 | 20 | 30 |

| Animal nuisance such as noise or dog fouling | 41 | 43 | 35 | 36 | 32 | 26 | 28 | 23 | 23 | 19 | 30 |

| Vehicles | |||||||||||

| Abandoned or burnt out vehicles | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Base | 940 | 900 | 920 | 930 | 1,070 | 1,070 | 1,090 | 1,010 | 860 | 910 | 9,700 |

Columns may not add to 100 per cent since multiple responses were allowed.

Table 4.19 shows that neighbourhood problems were generally perceived to be more common by those who lived in socially rented housing compared to owner occupiers and private renters. Drug misuse or dealing was most likely to be perceived to be a very or fairly common problem by those in socially rented accommodation, with a quarter (25 per cent) citing it as regular issue compared to 11 per cent of those in private rented housing and nine per cent of owner occupiers. This may be an effect of the association between tenure and area-deprivation as explained in Chapter 3.

Table 4.19: Percentage of people saying a problem is very/fairly common in their neighbourhood by tenure of household

Percentages, 2018 data

| Adults | Owner occupied | Social rented | Private rented | Other | All |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General anti-social behaviour | |||||

| Vandalism / graffiti / damage to property | 6 | 15 | 9 | 7 | 8 |

| Groups or individual harassing others | 4 | 12 | 5 | 4 | 6 |

| Drug misuse or dealing | 9 | 25 | 11 | 11 | 12 |

| Rowdy behaviour | 7 | 19 | 18 | 9 | 11 |

| Neighbour problems | |||||

| Noisy neighbours / loud parties | 6 | 19 | 15 | 8 | 10 |

| Neighbour disputes | 4 | 13 | 6 | 4 | 6 |

| Rubbish and fouling | |||||

| Rubbish or litter lying around | 26 | 38 | 32 | 35 | 30 |

| Animal nuisance such as noise or dog fouling | 29 | 39 | 23 | 24 | 30 |

| Vehicles | |||||

| Abandoned or burnt out vehicles | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Base | 6,190 | 2,250 | 1,160 | 110 | 9,700 |

Columns may not add to 100 per cent since multiple response were allowed

Perceptions of neighbourhood problems generally decreased with age, as shown in Table 4.20 below. For example, those aged 16-24 were more likely than all other age groups to view rowdy behaviour as a very or fairly common issue (reported by 16 per cent and three per cent respectively). However, the number of 16-24 year olds reporting this problem fell from last year (16 per cent in 2018 compared to 21 per cent in 2017[65]).

The association between age and the perceived prevalence of neighbourhood problems is not linear across all of the issues considered. Adults aged 35-44 were the most likely to perceive animal nuisance (such as noise or fouling) as being very or fairly common (36 per cent) with those in the younger and older age brackets of 16-24 and 75 plus less so (26 per cent and 23 per cent respectively).

Table 4.20: Percentage of people saying a problem is very/fairly common in their neighbourhood by age of respondent

Percentages, 2018 data

| Adults | 16 to 24 | 25 to 34 | 35 to 44 | 45 to 59 | 60 to 74 | 75 plus | All |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General anti-social behaviour | |||||||

| Vandalism / graffiti / damage to property | 10 | 9 | 10 | 9 | 6 | 3 | 8 |

| Groups or individual harassing others | 8 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 3 | 2 | 6 |

| Drug misuse or dealing | 12 | 13 | 13 | 15 | 11 | 6 | 12 |

| Rowdy behaviour | 16 | 15 | 14 | 11 | 7 | 3 | 11 |

| Neighbour problems | |||||||

| Noisy neighbours / loud parties | 16 | 13 | 12 | 9 | 7 | 3 | 10 |

| Neighbour disputes | 9 | 8 | 7 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 6 |

| Rubbish and fouling | |||||||

| Rubbish or litter lying around | 34 | 33 | 32 | 29 | 28 | 20 | 30 |

| Animal nuisance such as noise or dog fouling | 26 | 32 | 36 | 31 | 30 | 23 | 30 |

| Vehicles | |||||||

| Abandoned or burnt out vehicles | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Base | 680 | 1,300 | 1,370 | 2,390 | 2,540 | 1,430 | 9,700 |

Columns may not add to 100 per cent since multiple response were allowed

Table 4.21 shows that adults living in large urban areas were generally most likely to perceive each issue as being very or fairly common, whilst those in rural areas tended to be least likely to consider neighbourhood problems to be common.

Continuing the trend from recent years, the issue most commonly reported by those in large urban areas was rubbish or litter lying around (39 per cent), a problem only rated as very or fairly common by 21 per cent of those in accessible rural areas, and 14 per cent of adults living in remote rural areas.

Table 4.21: Percentage of people saying a problem is very/fairly common in their neighbourhood by Urban Rural classification

Percentages, 2018 data

| Adults | Large urban areas | Other urban areas | Accessible small towns | Remote small towns | Accessible rural | Remote rural | Scotland |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General anti-social behaviour | |||||||

| Vandalism / graffiti / damage to property | 12 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 4 | 3 | 8 |

| Groups or individual harassing others | 7 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 6 |

| Drug misuse or dealing | 14 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 6 | 6 | 12 |

| Rowdy behaviour | 16 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 4 | 4 | 11 |

| Neighbour problems | |||||||

| Noisy neighbours / loud parties | 13 | 11 | 7 | 9 | 5 | 5 | 10 |

| Neighbour disputes | 6 | 7 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 6 |

| Rubbish and fouling | |||||||

| Rubbish or litter lying around | 39 | 27 | 27 | 26 | 21 | 14 | 30 |

| Animal nuisance such as noise or dog fouling | 32 | 30 | 34 | 31 | 30 | 21 | 30 |

| Vehicles | |||||||

| Abandoned or burnt out vehicles | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Base | 2,970 | 3,250 | 840 | 580 | 1,030 | 1,030 | 9,700 |

Columns may not add to 100 per cent since multiple responses were allowed.

4.4.3 Personal Experience of Neighbourhood Problems

The previous section examined perceptions of neighbourhood problems by a range of socio-demographic and geographic characteristics. This section will now focus on personal experience of neighbourhood problems.

It is not always necessary to have direct personal experience of an issue to know about it or perceive it as a problem in an area. For example, in the case of vandalism, a person may not have experienced vandalism to their property, but may have seen other vandalised property in their neighbourhood.

In addition, what respondents define as “experience” is related to their own perceptions, beliefs and definitions. For instance, one respondent may consider witnessing drug dealing as experiencing the issue, whilst another respondent may only report experience of this problem if they personally have been offered drugs.

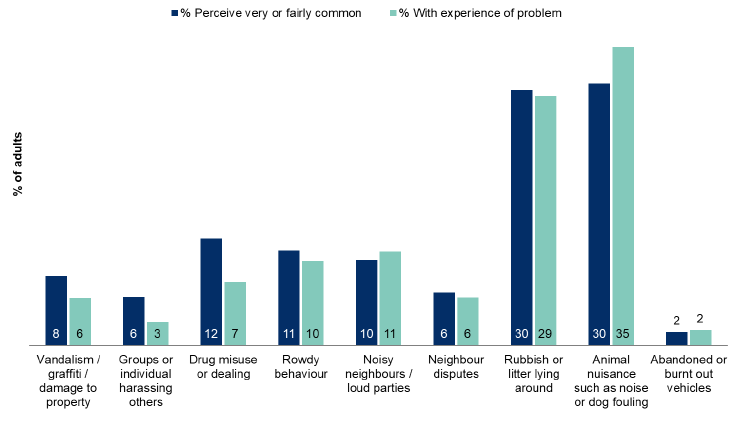

Figure 4.3 compares the perception that a neighbourhood problem is fairly or very common with reported experiences of that problem and shows that this varies depending on the problem. Twelve per cent of individuals believed drug misuse or dealing was a very or fairly common problem in their neighbourhood, yet only seven per cent of adults reported that they had personally experienced this. Conversely, 30 per cent of adults perceived animal nuisance to be a problem although 35 per cent of adults experienced it. The relationship between experiences and perceptions was much more evident for certain neighbourhood problems such as issues with neighbour disputes.

Figure 4.3: Perceptions and experience of neighbourhood problems

2018 data, Adults, (Base: 9,700)

Table 4.22 shows that although 46 per cent of all adults in Scotland reported that they had experienced no neighbourhood problems in 2018, this varied by area deprivation. Those living in the 20 per cent most deprived areas were least likely to report experiencing no problems, with around one-third (35 per cent) of adults experiencing no problems. In comparison, more than a half (54 per cent) of adults living in the least deprived areas experienced no problems. In all cases, animal nuisance was the most commonly experienced problem.

Table 4.22: Experience of neighbourhood problems by Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation

Percentages, 2018 data

| Adults | 1 - 20% most deprived | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 - 20% least deprived | Scotland |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General anti-social behaviour | ||||||

| Vandalism / graffiti / damage to property | 11 | 7 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 6 |

| Groups or individual harassing others | 6 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| Drug misuse or dealing | 16 | 10 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 7 |

| Rowdy behaviour | 17 | 12 | 8 | 6 | 7 | 10 |

| Neighbour problems | ||||||

| Noisy neighbours / loud parties | 18 | 14 | 9 | 7 | 7 | 11 |

| Neighbour disputes | 10 | 7 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 6 |

| Rubbish and fouling | ||||||

| Rubbish or litter lying around | 41 | 33 | 28 | 24 | 20 | 29 |

| Animal nuisance such as noise or dog fouling | 42 | 39 | 32 | 32 | 29 | 35 |

| Vehicles | ||||||

| Abandoned or burnt out vehicles | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| None | 35 | 40 | 47 | 51 | 54 | 46 |

| Base | 1,840 | 1,850 | 2,140 | 2,100 | 1,770 | 9,700 |

Columns may not add to 100 per cent since multiple responses were allowed.

Adults in socially rented accommodation were generally less likely than those in owner occupied and private rented housing to say they had experienced no neighbourhood problems (Table 4.23). In all tenure types, the most commonly experienced problems were animal nuisance or rubbish lying around (between 26 per cent and 39 per cent).

Table 4.23: Experience of neighbourhood problems by tenure of household

Percentages, 2018 data

| Adults | Owner occupied | Social rented | Private rented | Other | All |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General anti-social behaviour | |||||

| Vandalism / graffiti / damage to property | 4 | 9 | 6 | 4 | 6 |

| Groups or individual harassing others | 2 | 6 | 3 | 2 | 3 |

| Drug misuse or dealing | 5 | 14 | 8 | 8 | 7 |

| Rowdy behaviour | 7 | 14 | 15 | 12 | 10 |

| Neighbour problems | |||||

| Noisy neighbours / loud parties | 7 | 19 | 17 | 2 | 11 |

| Neighbour disputes | 4 | 10 | 6 | 7 | 6 |

| Rubbish and fouling | |||||

| Rubbish or litter lying around | 27 | 33 | 31 | 33 | 29 |

| Animal nuisance such as noise or dog fouling | 35 | 39 | 26 | 29 | 35 |

| Vehicles | |||||

| Abandoned or burnt out vehicles | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| None | 47 | 39 | 47 | 42 | 46 |

| Base | 6,190 | 2,250 | 1,160 | 110 | 9,700 |

Columns may not add to 100 per cent since multiple responses were allowed.

People living in remote rural areas were the most likely to report having experienced no neighbourhood problems in the last year (60 per cent; Table 4.24) and had the lowest proportion of adults reporting experience of rubbish lying around (15 per cent) or animal nuisance (24 per cent). Respondents living in large urban areas were the least likely to report experiencing no neighbourhood problems (40 per cent).

Table 4.24: Experience of neighbourhood problems by Urban Rural Classification

Percentages, 2018 data

| Adults | Large urban areas | Other urban areas | Accessible small towns | Remote small towns | Accessible rural | Remote rural | Scotland |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General anti-social behaviour | |||||||

| Vandalism / graffiti / damage to property | 7 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 6 |

| Groups or individual harassing others | 4 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| Drug misuse or dealing | 10 | 7 | 6 | 8 | 3 | 3 | 7 |

| Rowdy behaviour | 14 | 9 | 8 | 12 | 4 | 2 | 10 |

| Neighbour problems | |||||||

| Noisy neighbours / loud parties | 14 | 11 | 6 | 10 | 6 | 5 | 11 |

| Neighbour disputes | 6 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 6 |

| Rubbish and fouling | |||||||

| Rubbish or litter lying around | 37 | 27 | 27 | 27 | 23 | 15 | 29 |

| Animal nuisance such as noise or dog fouling | 36 | 34 | 40 | 35 | 36 | 24 | 35 |

| Vehicles | |||||||

| Abandoned or burnt out vehicles | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| None | 40 | 48 | 45 | 46 | 48 | 60 | 46 |

| Base | 2,970 | 3,250 | 840 | 580 | 1,030 | 1,030 | 9,700 |

Columns may not add to 100 per cent since multiple responses were allowed.

4.5 Discrimination and Harassment

4.5.1 Experiences of Discrimination and Harassment

The SHS explores whether respondents have experienced any kind of discrimination or harassment[66], in the last 12 months, whilst in Scotland. In 2018, one in 12 adults reported that they had experienced discrimination (eight per cent) and one in 17 had experienced harassment (six per cent) in Scotland at some point over the 12 months (Table 4.25).

People living in the 20 per cent most deprived areas were more likely to experience both discrimination (10 per cent) and harassment (seven per cent) compared to those living in the 20 per cent least deprived areas (seven per cent and four per cent respectively).

The wording of questions about discrimination and harassment in the SHS changed in 2018. In previous years the questions asked about experiences in ‘the last 3 years’, and from 2018 they refer to experiences in the last 12 months. The data is therefore not comparable with data reported on these topics in previous years’ surveys.

Table 4.25: Experience of discrimination and harassment by gender, age and level of deprivation

Row percentages, 2018 data

| Adults | Discrimination | Harassment | Base | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Yes | No | ||

| Gender | |||||

| Men | 8 | 92 | 6 | 94 | 4,320 |

| Women | 8 | 92 | 6 | 94 | 5,380 |

| Identified in another way | * | * | * | * | 0 |

| Refused | * | * | * | * | 0 |

| Age | |||||

| 16 to 24 | 14 | 86 | 9 | 91 | 680 |

| 25 to 34 | 12 | 88 | 7 | 93 | 1,300 |

| 35 to 44 | 9 | 91 | 7 | 93 | 1,370 |

| 45 to 59 | 8 | 92 | 6 | 94 | 2,390 |

| 60 to 74 | 5 | 95 | 4 | 96 | 2,540 |

| 75+ | 3 | 97 | 2 | 98 | 1,430 |

| Deprivation | |||||

| 20% Most Deprived | 10 | 90 | 7 | 93 | 1,840 |

| 20% Least Deprived | 7 | 93 | 4 | 96 | 1,770 |

| All | 8 | 92 | 6 | 94 | 9,700 |

Table 4.26 displays the proportion of adults who have experienced discrimination or harassment by a further range of demographic breakdowns: sexual orientation, ethnicity, religion, and whether the individual has a long term physical or mental health condition which has (or is expected to) last at least 12 months. It highlights that some groups were more likely than others to report having experienced discrimination or harassment including: those who are gay/lesbian/bisexual, recorded as a minority ethnic group or belong to a religion other than Christianity . Small base sizes for some groups – such as ‘gay/lesbian/bisexual’ - means that estimates can have relatively large degrees of uncertainty around them and should therefore be interpreted with caution.

Table 4.25 and Table 4.26 do not show the reasons behind experiences of discrimination and harassment, which can be but are not necessarily related to the equality characteristics presented. To get an understanding of this, those who have experienced such issues are also asked about the factors they believe may have motivated their experiences (as detailed below).

Table 4.26: Experiences of discrimination and harassment by sexual orientation, ethnicity, religion and long term physical/mental health condition

Row percentages, 2018 data[67]

| Adults | Discrimination | Harassment | Base | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Yes | No | ||

| Sexual Orientation | |||||

| Heterosexual/Straight | 8 | 92 | 6 | 94 | 9,490 |

| Gay/Lesbian/ Bisexual | 25 | 75 | 23 | 77 | 150 |

| Ethnicity | |||||

| White | 8 | 92 | 6 | 94 | 9,410 |

| Other minority ethnic group | 17 | 83 | 11 | 89 | 290 |

| Religion | |||||

| None | 9 | 91 | 6 | 94 | 4,690 |

| Church of Scotland | 4 | 96 | 3 | 97 | 2,470 |

| Roman Catholic | 9 | 91 | 7 | 93 | 1,310 |

| Other Christian | 9 | 91 | 6 | 94 | 1,000 |

| Another religion | 17 | 83 | 15 | 85 | 230 |

| Long term physical/mental health condition | |||||

| Yes | 11 | 89 | 8 | 92 | 3,330 |

| No | 7 | 93 | 5 | 95 | 6,330 |

| All | 8 | 92 | 6 | 94 | 9,700 |

4.5.2 Motivating factors

Adults who reported that they had experienced harassment or discrimination were asked what they think might have motivated this. Respondents were asked to provide spontaneous responses to these questions and where possible, the interviewer coded these answers into one of the main categories shown in Table 4.27 (e.g. age, disability, gender, and so on). As there were a wide range of options which adults could have provided (and the fact multiple reasons could be given), it was not possible to code every potential type of response in advance, which has resulted in high levels of ‘other’ reasons being recorded.

Table 4.27 shows that 19 per cent of respondents who had been discriminated against believed the reason behind this was their nationality. Other common motivating factors included the respondent’s age (15 per cent), health problem or disability (11 per cent), ethnicity (11 per cent), mental ill-health (10 per cent), gender (10 per cent) and accent (10 per cent).

Of those who had experienced harassment, 15 per cent cited their nationality as the perceived reason and 11 per cent cited their ethnicity, with ‘other reasons’ being the most common individual response (20 per cent).

Table 4.27: Reasons for discrimination and harassment

Percentages, 2018 data

| Adults | Discrimination | Harassment |

|---|---|---|

| Your age | 15 | 7 |

| Your sex or gender | 10 | 8 |

| Where you live | 8 | 6 |

| Your language | 3 | 5 |

| Your ethnicity | 11 | 11 |

| Your nationality | 19 | 15 |

| Your accent | 10 | 6 |

| Your social or educational background | 6 | 5 |

| Your sexual orientation | 4 | 4 |

| Your trans status, including non-binary identities | 0 | 0 |

| Sectarian reasons | 7 | 7 |

| Your religious belief or faith | 7 | 5 |

| Your mental ill-health | 10 | 7 |

| Any other health problems or disability | 11 | 10 |

| Other reason | 11 | 20 |

| Base | 750 | 550 |

Columns may not add to 100 per cent since multiple responses were allowed.

4.6 Community Engagement and Resilience

4.6.1 Resilience and preparedness for emergency situations

The SHS seeks to explore how prepared the population are for potential emergency situations.

It explores how much thought and/or activity households in Scotland had undertaken in preparation for issues like severe weather or flooding[68]. As shown in Table 4.28, in 2018 just under two thirds (64 per cent) of households in Scotland had given no thought to preparing for such situations, whilst a further 14 per cent had thought about it but had taken no action. Just one in 17 households (six per cent) said they were fully prepared.

Households in the most deprived areas were most likely to report having given no thought to preparing for issues like severe weather or flooding.

Table 4.28: Activity undertaken to prepare for events like severe weather or flooding

Column percentages, 2018 data

| Adults | 1 - 20% most deprived | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 - 20% least deprived | All |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Given it no thought | 72 | 71 | 59 | 56 | 60 | 64 |

| Thought about but haven't done anything | 13 | 13 | 16 | 15 | 15 | 14 |

| Thought about and have made some preparations | 10 | 10 | 17 | 19 | 19 | 15 |

| Thought about and am fully prepared | 3 | 5 | 7 | 9 | 6 | 6 |

| Don't know | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| All | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Base | 560 | 560 | 630 | 610 | 550 | 2,910 |

Table 4.29 shows the proportion of households with specific items readily available for potential use in the event of severe weather or flooding, by tenure and SIMD. In 2018, one in five households had an emergency kit prepared (20 per cent), just under two-fifths had a battery-powered radio (36 per cent) and three-fifths had a first aid kit (61 per cent). Households were more likely to hold copies of important documents, such as insurance policies, than the other items with 68 per cent of households having these readily accessible.

Availability varied across household types. Owner occupiers were more likely than social or private renter to have all emergency response items available. Households in the 20 per cent least deprived areas were more likely to have a working radio, first aid kit and copies of important documents available compared to households in the 20 per cent most deprived areas.

Table 4.29: Availability of emergency response items in household by tenure of household and Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation

Column percentages, 2018 data

| Adults | Owner occupied | Social rented | Private rented | Other | 20% Most Deprived | 20% Least Deprived | All |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| An emergency kit already prepared with essential items | 23 | 16 | 17 | * | 18 | 18 | 20 |

| A working radio with batteries | 41 | 28 | 26 | * | 27 | 37 | 36 |

| A first aid kit | 70 | 43 | 50 | * | 45 | 67 | 61 |

| Copies of important documents (like insurance policies) | 76 | 53 | 62 | * | 56 | 74 | 68 |

| Base | 1,860 | 660 | 370 | 30 | 560 | 550 | 2,910 |

Contact

Email: shs@gov.scot

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback