Scottish Budget 2025 to 2026: Equality and Fairer Scotland Budget Statement

The Equality and Fairer Scotland Budget Statement considers the impacts that decisions made in the Scottish Budget are likely to have on different groups of people in Scotland. It is a supporting document to the Scottish Budget and should be read alongside associated Budget publications.

Chapter 2: An overview of the 2025-26 Scottish Budget

This chapter sets out the estimated impact of the 2025-26 Scottish Budget on households across the income distribution as well as different household types and protected characteristics. It considers the overall level of public services received alongside a selected number of major policy measures announced at this budget.

Public services can play a vital role in advancing equality and fairness. For example, the social security system can play a crucial part in keeping people out of poverty and re-distributing income. Unlike spending on cash benefits, spending on public services, such as Health, Transport or Education, is not necessarily aiming at redistributing income. However, recent research from the Deaton Review has shown that it can also be highly redistributive and has become more so over the past 30 years (Institute for Fiscal Studies, May 2023).[1]

The analysis presented in this chapter shows that the Scottish Budget redistributes from high income households to those further down the income distribution, through both the tax and social security system, and through the delivery of public services.

2.1 Overall impact of the 2025-26 Budget

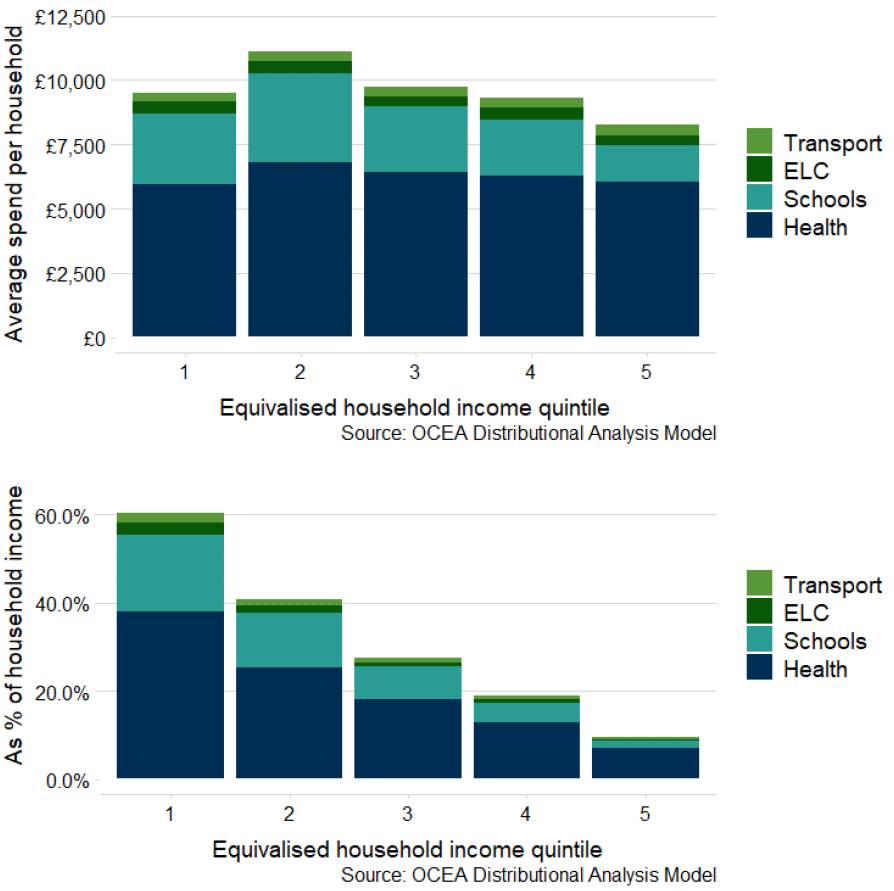

This section provides an overview of the estimated overall level of spending on public services received by households across the income distribution. It draws on new analytical capabilities developed by the Office of the Chief Economic Adviser (OCEA) and covers £24 billion of public spending, which is just under half of all resource spending in 2025-26. It includes Scottish Government resource spending on health, schools, funded early learning and childcare (ELC), and transport. It does not cover other areas or capital spending.

As illustrated in Figure 1, the analysis shows that the overall distribution of public spending on health, schools, transport and funded early learning and childcare is similar in cash terms across income groups, although when considered with the progressivity of the tax system, the overall tax and spending system system is redistributive. Spending is a greater share of household income for those in low income households across all of the areas of spending.[2]

In particular, in 2025-26:

- Health resource spending, including spending on NHS boards, community health and mental health services, is relatively flat in cash terms, albeit with less spending going to the bottom quintile. This is because the shape of the distribution is driven by the position of households with older people, where service usage is higher, and there are more younger people in the lowest quintile.

- Resource spending on schools (excluding free school meals or the school clothing grant) is focused on lower income households, both in cash terms and as a share of income, because households with children of school age tend to be more prevalent in lower income quintiles.

- Resource spend on Early Learning and Childcare (ELC) is driven by the position of households with 3 and 4 year olds and eligible 2 year olds in the income distribution. Average spend on households in the lower half of the income distribution is higher than spending in the upper half, both in cash terms and as a share of household income.

- Transport spending (including spending on concessionary fares, bus, rail and road) is higher for high income households than for low income households. Resource spending on bus services and concessionary travel is more focused on lower income households.

The profile of public spending across areas generally does not change significantly over time, however, changes in the overall level of spending can result in substantial redistribution to, or from, lower income households.

2.2 Analysis of selected key budget decisions

This section considers the impact of major policy decisions taken at this year’s Budget. Overall, there are hundreds of spending lines at Level 3 and Level 4. This makes it difficult to set out the changes in each line individually and to provide a succinct view of the cumulative impact of all decisions across both tax and spending. This year, the analysis therefore focuses on a select number of key decisions and looks at their equality and fairness impacts.

These budget decisions are illustrative and are not intended to cover all aspects of the budget. They have been selected with the following criteria in mind:

- Magnitude: The analysis has focused on decisions of a substantive financial scale.

- Substantive equality and fairness impact: The analysis has focused on decisions which could have a significant impact on equality and fairness, i.e. they might impact a large number of people; a number of different characteristics are affected; and/or there are significant intersectional impacts.

- Breadth: Decisions were also selected to ensure that a wide range of different policy areas and portfolios are reflected. The analysis presented includes decisions to increase, or maintain spending in cash terms.

The analysis draws on OCEA’s distributional modelling alongside the evidence gathered from portfolios, including six case studies which follow the six question approach developed in collaboration with the Equality and Human Rights Budget Advisory group (EHRBAG).

Eradicating Child Poverty

The 2025-26 Budget focuses on the delivery of the four priorities and the commitments set out in this year’s Programme for Government (PfG). ‘Eradicating child poverty’ is the top priority for the Scottish Government.

What is the key decision and which outcome is it trying to achieve?

The Scottish Government’s approach to ending child poverty is set out in ‘Best Start, Bright Futures’[4], which sets a path towards meeting the 2030 statutory child poverty targets.[5]

This Budget will continue to invest in a range of activity which supports the three drivers of poverty reduction: increasing income from social security and benefits in kind; increasing income from employment; and reducing the cost of living. These activities include:

- £768 million for the Affordable Housing Supply Programme

- Invest almost additional £800 million more in 2025-26 in social security benefits compared to 2024-25. This will bring our total expenditure on devolved benefits to over £6.9 billion for 2025-26.

- Funding the Network Support Grant and concessionary travel schemes by £464 million continuing to ensure bus services are not withdrawn from our most vulnerable communities and continuing to provide free bus travel for those under 22, as well as older people and those with eligible disabilities.

- Continue to invest around £1 billion through the Local Government settlement in continuing to deliver high quality funded early learning and childcare for 3 and 4 year olds, and eligible 2 year olds.

- Provide £21 million of investment to ensure Early Learning and Childcare and Children’s Social Care staff in the private and voluntary sector area are paid the real living wage.

- Provide £8 million investment for the continued development of flexible, affordable childcare for priority families in our Early Adopter Communities.

- Work with local government to deliver on our commitment to expand free school meals provision for Primary 6/7 children in receipt of the Scottish Child Payment supporting around 25,000 pupils to access nutritious and healthy food, backed by investment of £37 million in 2025-26.

- Deliver up to £3 million for a Bright Start Breakfasts pilot, which will test the delivery of free breakfast clubs and kick starts more breakfast delivery across Scotland.

- Continue to support students with free tuition and providing packages of support for vulnerable higher education students, through bursaries for eligible students, and Education Maintenance Allowance for 16-19 year olds from low-income families.

- Invest over £300 million in energy efficiency and clean heat measures which also help to reduce household energy bills on a lasting basis and reduce the cost of living for households.

- continue to invest in our employability programmes, providing £90 million to drive our commitment to reduce child poverty through supporting those already in work, help more people back into work and address long term economic inactivity.

In addition, in the coming financial year the Scottish Government will develop the systems necessary to effectively scrap the impact of the two child cap in 2026. To that end the Scottish Government has provided funding to develop the delivery mechanism in this Budget and will seek to accelerate the timetable if at all possible.

How do the budget decisions impact on different people and places?

No single policy intervention will end child poverty; rather the cumulative impact of a package of interventions is necessary to keep as many children out of poverty as possible.

Scottish Government analysis[6] estimates (February 2024), that 100,000 children will be kept out of relative poverty in 2024-25 as a result of Scottish Government policies, including the Scottish Child Payment. This means that the relative child poverty rate is estimated to be around 10 percentage points lower than it would have been without these policies.

Some of the equality and fairness impacts are set out below. Further detail is available in the respective case studies.

- Housing costs are an important factor related to income inequality and poverty. Research evidence suggests that poverty is one of the core drivers of homelessness in the UK, and Scotland specifically. Evidence indicates that Scotland’s higher share of renters in affordable social housing helps to keep poverty rates lower.[7] Scottish Government estimates further suggest that lower social rents benefit approximately 140,000 children in poverty each year.[8]

- Social Security: In 2024-25, the Scottish Child Payment is projected to impact the relative child poverty rate by 6 percentage points, meaning it will keep 60,000 children out of relative poverty in that year. Equality Impact Assessments show that women, disabled people and ethnic minorities are likely to benefit most from new Scottish benefits such as the Scottish Child Payment.[9] Distributional analysis carried out by OCEA and published alongside the Budget shows that the Scottish Child Payment is the largest single contributor to the improved financial resources of low-income households relative to the rest of the UK.

- Expansion of Free School Meals to pupils whose families are in receipt of Scottish Child Payment (SCP) in Primaries 6 and 7 means that funding will reach those who need it most. The policy will be focused on households in the bottom half of the income distribution with most lone parent households remaining eligible. Parents of families eligible to receive free school meals through SCP are also younger on average than under universal provision.

- Employability: Work to tackle economic inactivity and support people into fair, sustainable jobs, and to ensure that work pays for everyone through better wages and fair work, is central to delivering many of the Scottish Government’s ambitions around inclusive growth, eradicating child poverty, and tackling severe and multiple disadvantage. Funding for delivery of devolved employability services through the No One Left Behind approach includes enhancing support for parents and bringing together a range of services to help priority families increase their income from employment.

- Early Learning and Childcare: Evidence from the EQIA (2023) of School age childcare shows particularly positive impacts for younger parents, families with a disabled child of school age, or for families with a disabled adult and school age children, as well as for women.[10]

- Mitigating the impacts of the two child limit: This new support could be worth over £3,500 per year to families hit by the cap and, once implemented, could help to lift thousands of children out of poverty in Scotland and reduce the depth of poverty faced by many more. The IFS estimate that if this was mirrored across the UK, mitigation could keep 500,000 children out of poverty by the time it is set to roll out in full.

How will the impact of the policy decisions be evaluated?

The Child Poverty evaluation strategy[11] sets out specific plans for ongoing assessment of progress towards the targets. This includes careful monitoring of poverty rates, annual assessment of range of indicators focusing on the three drivers of poverty, and evaluations of individual policies.

To support policy evaluations of impact, the Child Poverty policy evaluation framework[12] provides a shared understanding on how to measure the impact of individual policies on child poverty. This includes setting common definitions, providing guidance in identifying child poverty outcomes, setting the rationale for data collection and presenting options.

Taxation

The revenues from devolved tax decisions have been vital for investment in public services. Scottish Income Tax alone is forecast to increase funding for the Scottish Budget by £838 million in 2025-26, compared to if devolution of these powers had not occurred.

What are the key decisions and which outcome are they trying to achieve?

Tax measures announced in this Budget are expected to raise £54 million in 2025-26 relative to inflationary uprating. The Income Tax policy package, which is expected to generate £52 million, aims to maintain Scotland’s progressive tax system. It will continue to ensure that more than half of taxpayers pay less Income Tax in Scotland than in the rest of UK in 2025-26, and until the end of the Parliament, while raising revenue for the Scottish Budget. Income Tax applies to taxable income, regardless of protected characteristic. Therefore, any differential impact on protected characteristics will simply reflect their distribution in the taxpayer population.

For Scottish Landfill tax (SLfT), the increased rates ensure that SLfT continues to provide appropriate fiscal incentives to support waste and circular economy targets. The increase also ensures that the rates remain consistent with UK landfill tax rates to reduce the risk of waste tourism. There is no evidence that the policy will affect protected characteristics or socio-economic disadvantage.

Changes in Additional Dwelling Supplement (ADS) are intended to support the Scottish Government’s drive to protect opportunities for first-time buyers in Scotland, reinforcing the progressive approach in place for Land and Buildings Transaction Tax (LBTT) rates and bands.

Non-domestic rates (NDR) are a tax on non-domestic properties. The NDR system aims to provide fairness to all ratepayers. Given the universal nature of non-domestic rates, and the lack of information on the characteristics of non-domestic property owners or occupiers, or ratepayers, it is not possible to distinguish any potential differential impact on different sectors of society based on protected characteristics or socio-economic status.

| Tax | Tax forecast changes in £m |

|---|---|

| Income Tax | 52 |

| LBTT | 32 |

| Scottish Landfill Tax | 6 |

| Non-Domestic Rates | -36 |

| Total | 54 |

How do the budget decisions impact on different people and places?

Distributional analysis published alongside the Budget[13] outlines the impacts of Income Tax policy changes at a household level for various characteristics, including income, age and by priority family types. It shows that:

- Scottish tax policy changes made in this Budget – increases to the Basic rate and Intermediate rate Threshold combined with freezes in the Higher, Advanced and Top rate thresholds – mean that almost half (47 per cent) of Scottish households are better off, with over three-quarters (76 per cent) of households either better off or unaffected as a result of these measures.

- Increases to the Basic and Intermediate rate thresholds have a small positive impact in the bottom half of the income distribution. The negative impact of frozen thresholds principally falls on the highest earning 20 per cent of households, with the top 10 per cent paying an average of 0.1 per cent of their income (around £130) more.

- The Income Tax policy decisions at this Budget further increase the progressivity of the income tax system, with the increase in the thresholds benefitting households in the lower half of the income distribution by a small amount (up to £12).

How will the impact of the policy decisions be evaluated?

Scotland’s Tax Strategy: Building on our Tax Principles, which has been published alongside the 2025-26 Scottish Budget recognises the need to build on past evaluations across the devolved and local tax system, ensuring that significant policy decisions are transparently monitored and assessed as further data and evidence emerges.

As part of this, we will formally evaluate the impact of the changes to Income Tax in 2023-24 and 2024-25 once outturn data is available, and conduct, our first five-year review of LBTT by the end of this Parliament.

Benefits

Pension Age Winter Heating Payment

The Scottish Government will provide universal support through the introduction of Pension Age Winter Heating Payments (PAWHP) next year ensuring a payment for every pensioner household in winter 2025-26.

What is the key decision and which outcome is it trying to achieve?

Pensioner households in receipt of a relevant qualifying benefit, such as Pension Credit, will be receiving Pension Age Winter Heating Payments of £300 or £200, depending on their age. Meanwhile all other pensioner households will receive £100 from next winter, providing them with support not available anywhere else in the UK.

Extending entitlement for PAWHP to all pensioner households will provide all older people with additional money to meet increased heating costs during the winter. Having additional financial support can encourage them to heat their homes for longer whilst also helping to tackle fuel poverty. Cold temperatures can be particularly dangerous for those with pre-existing health conditions. Older people are also more likely to live in ‘colder’ and ‘harder to heat homes’, and spend more time indoors according to a recent survey carried out by Age Scotland.

The policy aligns closely with the Scottish Government’s Wealthier and Fairer Strategic Objectives, but also links with the Scottish Government’s strategic priorities to support older people and the cost of living crisis.

How do the budget decisions impact on different people and places?

The policy will provide some level of support to all pensioners and re-introduces support to around 900,000 pensioners who would not have received support next winter otherwise.

This approach will likely have a positive impact on vulnerable pensioners who are not eligible for Pension Credit, or who do not take up their entitlement, but still face financial difficulties and would benefit from this support, including older individuals, e.g. those over 80, who are more vulnerable to the effects of cold weather due to health conditions or reduced mobility.

It provides an efficient means of delivering support to pensioner households in Scotland; mitigating the increases in energy costs; and providing that cost of living support for all pensioner households, helping reduce pensioner poverty and support fixed pensioner household incomes.

Since the decision to move to a targeted benefit, the introduction of £100 payments provides an additional benefit to households in the bottom half of the income distribution. This is progressive as a share of household income.

The UK and Scottish Governments will continue to progress work on improving Pension Credit up-take to ensure those entitled receive the higher value payment.

The universal entitlement to, and automatic payment of, PAWHP means that take-up would be high and will ensure all older people will receive additional money during winter which will encourage them to heat their homes for longer.

How will the impact of the policy decisions be evaluated?

As with all social security benefits, we will carry out an evaluation following the delivery of the benefit and continue to investigate ways of improving the benefit after it has been launched. The Scottish Government will put in place a monitoring and evaluation plan for PAWHP. Monitoring the impact of the PAWHP will be a continuous process and where any unintended consequences are identified, we will consider what steps can be made to minimise any negative impact. We will collate management information to monitor the characteristics of recipients and will undertake qualitative research to test whether PAWHP is meeting its policy intentions. This will inform any future consideration of variations to policy or delivery arrangements.

Carer Support Payment

What is the key decision and which outcome is it trying to achieve?

The ‘earnings threshold’ for Carer Support Payment (and Carer’s Allowance for those who receive this in Scotland) will be increased from £151 to £196 from April 2025. Carer Support Payment and Carer’s Allowance are income-replacement benefits for people who are providing 35 hours or more of care a week to someone getting certain disability benefits. The change means carers will be able to earn an additional £45 per week and still receive support from these benefits, helping remove barriers to work, provide more stable support, and allowing for increased incomes. The new threshold will also align with the threshold for Carer’s Allowance for those in England and Wales. This change will support national outcomes around Health and tackling Poverty, and will help in meeting our overall aims for Carer Support Payment, in particular that it provides stability and support for carers to have access to opportunities outside of caring, where possible and should they wish to do so.

How do the budget decisions impact on different people and places?

The change will disproportionally affect women, as around 69 per cent of those receiving Carer’s Allowance (the benefit Carer Support Payment is replacing) are women. It is likely to also have more impact on carers of working age, and those on lower incomes. The change may have less impact on those with the most intensive caring roles who may be unable to work. The increase sets the earnings threshold at a level which is 16 times the hourly National Living Wage. This will allow carers to earn more from work while still receiving support, and enable carers to work 16 hours a week which is a common part-time working pattern. This could improve incomes and access to work for women in particular. No differential impacts on carers have been identified in relation to the protected characteristics of religion and belief, marriage and civil partnership, pregnancy and maternity, sexual orientation or gender reassignment. Neither have particular impacts been identified on the rights of children and young people. Clear communications which are accessible for a broad range of carers will be needed around changes to the earnings threshold and what this means for carers applying for, and already receiving the benefit, to remove potential barriers to understanding entitlements and accessing support for some groups of carers.

How will the impact of the policy decisions be evaluated?

The impact of the change will be examined as part of the wider evaluation of Carer Support Payment, and monitored as part of ongoing work on Carer Support Payment, including through consideration of management information, research with clients, official statistics and engagement with internal and external stakeholders.

Pay and workforce

Public sector pay and workforce is a significant driver of budget spend, with spending on public sector pay now accounting for over half of the entire Scottish resource budget. There are around 600,000 people employed in the public sector in Scotland, accounting for 22.1 per cent of total employment in Scotland.

What is the key decision and which outcome is it trying to achieve?

The Scottish Government published a revised Pay Policy as part of the 2025-26 budget, which commits to above inflation awards. The policy set pay metrics as a pay envelope of 9 per cent over 2025-26, 2026-27 and 2027-28. Employers will have some flexibility to configure multi-year proposals within the 9 per cent envelope.

The Scottish Government’s recent investment in supporting pay deals for public sector workers reflects the important roles that they do and its commitment to deliver high quality, person-centred public services. The aims for the pay metrics will be to set a policy framework to deliver fair, affordable, sustainable and value-for-money pay for the devolved public sector in Scotland.

The ‘Public Sector Pay Policy’ sets the overarching framework in which public bodies can make individual choices on the impact of the strategy on their own circumstances, underpinned by an Equality and Fairer Scotland Impact assessment. Public bodies have the flexibility to draw up their own pay proposals to take into account local pay issues such as recruitment and retention, equality, and the impact of the low pay measures on other staff. The pay negotiation principles within the strategy actively encourage employers to take into account their own staffing profile, local evidence, views of staff and unions and equality issues in framing their pay proposals.

How do the budget decisions impact on different people and places?

The pay metrics set out in the Public Sector Pay Policy apply to all public sector workforces across Scotland including NHS Scotland, firefighters and police officers, teachers, and further education workers. The Policy applies to core Scottish Government (except senior civil servants, for whom pay is a reserved matter) and 71 public bodies including non-departmental public bodies, public corporations and agencies.

The Policy expects employers to take a progressive approach to their pay awards and requires employers to pay at least the ‘Real Living Wage’. As noted in previously published Equality Impact Assessment on pay policies[14], this will help support those living on low incomes. Recent analysis also indicates there are higher proportions of women, people with a disability, people from a minority ethnic background and younger employees among lower earners. Therefore any individual pay proposals which target higher increases for lower earners will in many cases provide a positive benefit.

There is also a higher likelihood of employees with a protected characteristic living within a lower income household. Poverty rates tend to be higher among the following groups: youngest adults; households where someone is disabled; single mothers; LGB+; ethnic minorities and particularly Pakistani and Chinese ethnic groups; and/or Muslim adults.

This may also help in working towards reducing the gender pay gap within the public sector as it should increase the overall base levels of pay for lower earners where traditionally women are overly concentrated.

How will the impact of the policy decisions be evaluated?

The Scottish Government collects information to enable respective teams to have oversight and identify those employers at risk of potential inequalities, such as lower paying organisations or those with longer journey times than the average.

Social Security Assistance

| 2023-24 outturn | 2024-25 outturn (Autumn Budget Revision) | 2025-26 budget | Change 2024-25 to 2025-26 |

|---|---|---|---|

| £5.2 billion | £6.0 billion | £6.8 billion | £0.8 billion |

Over the last six years, the Scottish Government has paid clients £17 billion through fourteen benefits, seven of which are unique to Scotland. The Scottish Government currently pay benefits to over 1.4 million people – around 1 in 4 people in Scotland.

What is the key decision and which outcome is it trying to achieve?

This is the decision to make provision to fund the Social Security Assistance level 3 Budget. This includes all social security benefits administered by Social Security Scotland and the Scottish Welfare Fund. It should be noted that benefits expenditure is demand-led, and cannot be controlled in the same way as other budgets where spending limits can be set. It also includes the decision to uprate all benefits in line with September CPI inflation.

This Budget invests almost £800 million more in 2025-26 in social security benefits compared to 2024-25.

How do the budget decisions impact on different people and places?

The benefits delivered by Social Security Scotland primarily provide targeted payments to support low-income families to alleviate poverty; and financial support to disabled people to compensate them for the additional costs associated with disabilities. There are also benefits provided to financially support people caring for disabled people.

Social Security Scotland spend supports the achievement of a Fairer Scotland in a number of ways, including:

- Reducing Child Poverty. In 2024-25, the Scottish Child Payment is projected to impact the relative child poverty rate by 6 percentage points, meaning it will keep 60,000 children out of relative poverty in that year.

- Reducing Income Inequality: Distributional modelling by the Scottish Government and the Institute for Fiscal Studies shows that changes made to the tax and welfare system by the Scottish Government in previous budgets has served to reduce inequality and target financial support at those who need it most

- Reducing Poverty and Protecting Households: There is emerging evaluation evidence that the new devolved benefits administered by Social Security Scotland are positively contributing to reducing financial pressure on households, reducing poverty, debt, material deprivation and food insecurity.[15]

- Promoting Equality: Equality Impact Assessments show that women, disabled people and people from minority ethnic communities are likely to benefit most from new Scottish benefits, such as the Scottish Child Payment.[16]

- Improving Health: Early evaluation evidence of benefits such as the Scottish Child Payment[17], Best Start Foods[18] and Best Start Grant[19] show that these benefits are improving health outcomes through, for example, enabling parents to provide more, and better quality food for their children.

- Improving Wellbeing: Evaluation evidence shows the introduction of new family benefits has led to improved family wellbeing through reducing money-related stress and anxiety for parents, improving children’s wellbeing through having their basic needs met.[20]

- Increasing Social Participation: The evaluation of Young Carer Grant[21] shows that the grant is helping young carers improve their own quality of life by taking part in opportunities which are the norm for their non-caring peers.

- Supporting Employment: Evaluation evidence shows Job Start Payment helps meet up-front costs of a new job, support young people to take up employment and increase confidence.[22] Evidence also shows that Young Carer Grant is supporting carers with employment and training.

How will the impact of the policy decisions be evaluated?

The Scottish Government’s approach to evaluation of the first wave of benefits that were devolved to Scotland was published in 2019.[23] Since then, the government has published eight evaluation reports under this strategy. Evidence has been drawn together from a variety of sources, including management information, research conducted by Social Security Scotland, official statistics and bespoke qualitative research with clients and other organisations. This has enhanced the government’s understanding of the impact of the benefits on clients’ experiences and outcomes.[24]

Further work is planned for 2025, including the publication of the next phase of evaluation of the Five Family Payments.

Affordable Housing Supply Programme

| 2023-24 outturn | 2024-25 outturn (as per Autumn Budget Revision) | 2025-26 budget | Change 2024-25 to 2025-26 £m |

|---|---|---|---|

| £707.8 million | £595.9 million | £767.7 million | £171.9 million |

What is the key decision and which outcome is it trying to achieve?

The budget decision is to increase the funding for the Affordable Housing Supply Programme (AHSP) from £595.9m in 2024-25 to £767.7m in 25-26 .

The AHSP aims to increase the supply of affordable homes across Scotland to support Scottish Government meeting its target of delivering 110,000 affordable homes by 2032 with at least 70 per cent for social rent and 10 per cent in rural and island communities. The AHSP programme contributes to the following National Outcomes:

- Health

- Communities

- Human Rights

- Education

- Children

- Poverty

- Economy

- Environment

How do the budget decisions impact on different people and places?

The majority of the programme is delivered across Scotland using the Strategic Housing Investment Framework (SHIF). The framework determines the allocation of funding to 30 of the 32 local authority areas (excluding Glasgow City Council and City of Edinburgh Council which includes funding from the Local Government Settlement). The SHIF formula takes into account four indicators: affordability; deprivation; rurality and homelessness. Local Authorities also have discretion to apply the available funding to local strategic priorities.

Local Authorities have statutory duties to assess local housing requirements and develop local housing strategies used to identify areas for AHSP funding. These should be underpinned by impact assessments that highlight which groups are affected at a local level as this will differ across Scotland.

Housing costs are an important factor related to income inequality and poverty. Research evidence suggests that poverty is one of the core drivers of homelessness in the UK, and Scotland specifically. Evidence indicates that Scotland’s higher share of renters in affordable social housing has helped to keep poverty rates lower in the past.[26] Scottish Government estimates further suggest that lower social rents benefit approximately 140,000 children in poverty each year.[27] Evidence also indicates that people with a disability or older people are more likely to experience fuel poverty or be living in underheated homes.[28] The AHSP’s support for affordable social rent properties and homes that meet energy efficient building standards thereby has a positive impact for these groups.

The programme budget reduced between 2023-24 and 2024-25 but has now increased in 2025-26. This budget increase means that while groups are not expected to be affected differently, the scale and pace of delivery that the programme is able to achieve across Scotland has been positively affected. This may result in local authorities being able to progress more of their local priorities than in recent years.

How will the impact of the policy decisions be evaluated?

Scottish Government directly monitors the impact of the programme through the publication of Official Quarterly Housing Statistics.

Concessionary Fares

| 2023-24 outturn | 2024-25 budget (as per Autumn Budget Revision) | 2025-26 budget | Change 2024-25 to 2025-26 £m |

|---|---|---|---|

| £357.5 million | £370.4 million | £414.5 million | N/A |

This is a demand led scheme. Final figures for the current financial year will not be available until the new financial year once all claims for operators have been received.

The overall aim of Concessionary Fares policy and the budget attached to it is to provide Scotland-wide free bus travel to all residents of Scotland aged under 22, eligible disabled people and everyone aged 60 and over.

What is the key decision and which outcome is it trying to achieve?

This is the decision to make provision to fund the Concessionary Fares policy, and to maintain the existing eligibility to the National Concessionary Travel Schemes for those who currently benefit.

This is a demand led scheme, and final figures for each financial year are not available until the new financial year, once all claims for operators have been received.

The key objectives of the concessionary travel scheme for older and disabled people include:

- allowing older and disabled people improved access to services, facilities and social networks, promoting social inclusion;

- improving health by promoting a more active lifestyle;

- promoting a modal shift from private cars to public transport.

In addition, extending free bus travel to all children and young people under 22 aims to improve access to education, leisure and work, while enabling them to travel sustainably early in their lives, and contributes to tackling child poverty.

How do the budget decisions impact on different people and places?

The Concessionary Fares scheme tackles a number of inequalities[29], for example

- People on lower incomes have less access to private modes of transport and are more reliant on public transport. People on lower incomes are more likely to use bus services and to do so more frequently than those on higher incomes. There are more older and younger people positioned in the lower half of the income distribution.

- Access to, and affordability of, public transport remain key issues for people on lower incomes. Evidence of the experiences of low-income families indicates that transport often determines and constrains their options in terms of household spending and their day-to-day experiences. Transport is required for day-to-day engagement with services and support networks including accessing healthcare, education, childcare, caring responsibilities, employment, shopping and engaging in leisure activities.

- People aged under 22 rely on buses for transport more than any other age group.

- Disabled adults are more likely to use the bus than non-disabled adults and are less likely to drive.

- Particular minority ethnic groups are more likely to be reliant on bus travel and also more likely to be in poverty than the majority white population.

Whilst the Scottish Government has no plans to extend the concessionary travel schemes beyond the current eligibility criteria or to amend the scope of the existing schemes, it is committed to further work to consider better targeting of public funds towards supporting access to public transport for those who need it most, including consideration of concessionary travel support for those experiencing financial poverty.

How will the impact of the policy decisions be evaluated?

Uptake and registration data for the scheme are routinely monitored. A baseline and one-year-on report have already been published on the concessionary scheme for under-22s and further evaluation will take place up to five years post-implementation. The Older and Disabled People’s scheme will also be evaluated in 2025-26.

Transport spend and perception of affordability is routinely monitored via questions asked in the Scottish Household Survey. This allows for analysis of spend level on public transport and whether this is affordable by socioeconomic background, protected characteristics, and geographic location. This feeds into monitoring and evaluation of the National Transport Strategy.

Employability

| 2024-25 budget | 2025-26 budget | Change 2024-25 to 2025-26 £m |

|---|---|---|

| £90 million | £90 million | 0 |

What is the key decision and which outcome is it trying to achieve?

This relates to the decision to maintain the budget for Employability to support delivery of all-age, person-centred employability support through the Scottish Government’s three-year Employability Strategy 2024-27.

No One Left Behind is the approach to devolved employability support between Scottish and Local Government, which provides flexible and person-centred support to support people – particularly those facing multiple barriers – to move into the right job, at the right time.

Of the 67,150 people supported under the No One Left Behind approach between April 2019 and June 2024, 20,743 people (31 per cent) entered employment.

How do the budget decisions impact on different people and places?

Evidence identifies a number of challenges the programme is tackling[30] including:

- Individuals from socio-economically disadvantaged backgrounds are more likely to experience barriers to participation in the labour market, such as lower levels of education and social capital, fewer opportunities to enter and progress in employment, and less access to flexible working for health or caring responsibilities.

- Despite relatively low unemployment rates, economic inactivity remains a concern, with a large proportion of this group being people reporting as long-term sick or disabled. There is local variation, with areas of high unemployment also tending to have high economic inactivity.[31]

- Many individuals face significant challenges and barriers to obtaining and sustaining work, including disabled people, those with long-term health conditions, lone parents and people from minority ethnic groups.

- The proportion of unemployed people who are long-term unemployed increases with age.

- Young people (aged 16-24) are more likely to be unemployed than older age groups and are vulnerable to long term employment ‘scarring’. Young people (18-24) are more likely to earn less than the ‘real Living Wage’ and are more likely to be financially vulnerable and in unmanageable debt.[32]

- Disabled people are less likely to be in employment than non-disabled people, earn less on average, are less likely to be employed in contractually secure work, less likely to have access to fair work, and are more likely to be under-employed, work part-time and work in lower-paid occupations.[33]

- The employment rate for people from minority ethnic groups has been consistently lower than for white people and, compared with the general population in Scotland, they are more likely to earn low income and be in relative poverty.[34]

- Women experience a range of barriers in the labour market that lead them to be paid less on average than men, which drives the gender pay gap. These barriers relate to the type of jobs women are more likely to do (job selection), how much these jobs pay (job valuation) and whether they can move into higher-paid jobs (job progression). Women (and particularly minority ethnic women) are more likely to be in insecure work and are over-represented in sectors that have historically low pay, low progression and low status, but that can provide more flexibility to allow women to undertake caring responsibilities.[35]

- People with multiple protected characteristics can face heightened barriers to employment[36], for example:

- intersectional barriers further hamper women’s opportunities, such as those experienced by disabled women, minority ethnic women and women aged over 50. Women experiencing the menopause while in work can require additional support;

- the ethnicity employment rate gap for women has been consistently higher than the gap for men, and a non-disabled white person is more than twice as likely to be in employment than a disabled person from a minority ethnic group.

Work to tackle economic inactivity and support people into fair, sustainable jobs, and to ensure that work pays for everyone through better wages and fair work, is central to delivering many of the Scottish Government’s ambitions around inclusive growth, eradicating child poverty, and tackling severe and multiple disadvantage. The Budget will deliver all-age, person-centred employability support through the No One Left Behind approach, prioritising those who face complex barriers to accessing the labour market. The Scottish Government has an ambition to at least halve the disability employment gap in Scotland by 2038 (from a 2016 baseline), and the PfG commits to introducing enhanced specialist support for disabled people across all 32 local authorities by Summer 2025.

How will the impact of the policy decisions be evaluated?

An implementation evaluation covering No One Left Behind was published in August 2023, and the Scottish Government is committed to ongoing evaluation of devolved employability services. Quarterly information is collected from the 32 Local Employability Partnerships, including participant characteristics aligned with census data, which informs quarterly statistical publications.

Annual updates of the No One Left Behind Strategic Plan 2024-27 will be published.

Alcohol and Drugs Policy

| 2023-24 outturn | 2024-25 outturn | 2025-26 budget | Change 2024-25 to 2025-26 £m |

|---|---|---|---|

| £93.8 million | £80.4 million | £80.9 million | £0.5 million |

£19 million of Alcohol and Drug Partnership funding baselined for 2025-26, i.e. moved from Alcohol and Drugs to NHS Territorial Health Board allocations.

On a like for like basis, the budget has remained broadly static in cash terms.

Through the National Mission on alcohol and drugs, the Scottish Government aims to reduce drug deaths and improve the lives of those impacted by drugs and alcohol.

What is the key decision and which outcome is it trying to achieve?

The decision in this case is to broadly maintain the budget (in cash terms) for Drugs and Alcohol Policy.

The National Mission aims to achieve six outcomes, (with some of the related activity in each case):

The majority of drug and alcohol funding to local areas is distributed on an adjusted National Resource Allocation (NRAC) formula to ensure that areas of most need are prioritised.

- Outcome 1: Fewer people develop problem drug use: delivering a set of Standards for children and young people that outline what they should expect when seeking help for a drug or alcohol problem, and develop a consensus statement with Public Health Scotland on prevention of substance use harm amongst children and young people.

- Outcome 2: Risk is reduced for people who take harmful drugs, including opening drug checking facilities in Dundee, Glasgow and Aberdeen and continuing to expand the provision of naloxone – a lifesaving medicine to reverse an opioid overdose. Additionally, continuing to improve the Rapid Action Drug Alerts and Response (RADAR) surveillance system.

- Outcome 3: People at most risk have access to treatment and recovery. increasing the number of residential rehabilitation beds in Scotland from 425 to 650 and increase the number of people receiving public funding for their placement to 1,000 a year by 2026.

- Outcome 4: People receive high quality treatment and recovery services. publishing a National Specification for drug and alcohol treatment and recovery services in 2025 and fully implementing the ten Medicated Assisted Treatment (MAT) Standards by April 2026. Also continuing to deliver the Workforce Action Plan to ensure a resilient, skilled and trauma-informed workforce.

- Outcome 5: Quality of life is improved for people who experience multiple disadvantage including improving mental health and substance use treatment to support the delivery of MAT 9, and ensuring the justice system is closely aligned to support those with lived and living experience.

- Outcome 6: Children, families and communities affected by substance use are supported. ADPs are implementing the Families Framework and the Scottish Government is developing Family Inclusive Practice pathways, and also working to improve support for women who use drugs.

How do the budget decisions impact on different people and places?

A systematic evidence review was carried out to support the Equality Impact Assessment work for the strategy development and is used as a live document. Some of the high level issues are set out below:

- Drug and alcohol death rates are closely linked to deprivation[38]. In 2023[37], people in the most deprived areas of Scotland were 15.3 times more likely to die from drug misuse than people in the least deprived areas and 4.5 times as likely to die of alcohol-specific causes.[39]

- Around 7 in 10 people starting specialist drug or alcohol treatment in Scotland are male.[40] However, the Scottish Government has concern about a disproportionate increase in drug deaths among females.

- The age profile of drug misuse deaths, and alcohol-specific deaths, has become older over time.[41]

- There is limited data in relation to disability, race/ethnicity, religion, sexual orientation and gender identity.[42]

How will the impact of the policy decisions be evaluated?

A set of metrics has been developed to monitor progress and is reported in the National Mission Monitoring Report.

The National Mission is being independently evaluated by Public Health Scotland (PHS). The National Mission Evaluation Framework[43] was published by PHS in May 2024. Lived and living experience is being consulted throughout the evaluation process and a lived experience survey will run until the end of December 2024. The Scottish Government has also commissioned individual evaluations of key policy areas, such as residential rehabilitation, which will also be led by PHS. The final evaluation report will be published in 2026.

International Development

| 2023-24 outturn | 2024-25 outturn | 2025-26 budget | Change 2024-25 to 2025-26 £m |

|---|---|---|---|

| £12.3 million | £11.5 million | £12.8 million | £1.3 million |

The budget provides for an ‘International Development Fund’ to support and empower our partner countries, which includes a ‘Humanitarian Emergency Fund’ component which responds to international humanitarian crises.

What is the key decision and which outcome is it trying to achieve?

This decision is to increase (in cash terms) the budget for the International Development Fund.

This spend relates mainly to activities in Malawi, Rwanda, Zambia and Pakistan which are the Scottish Government’s priority partner countries as set out in Scotland’s International Strategy[44] (all of which are lower-income or lower-middle income countries with significant inequalities challenges).

Decisions around international development spend are informed by detailed consultation with each of the governments in partner countries, as well as local civil society organisations in each country, concerning the inequalities the funding will reduce. Preliminary EQIA’s have also been conducted, and gender equality is mainstreamed across all new international development programmes.

Decisions around humanitarian spend are shaped by the Scottish Government’s Humanitarian Emergency Panel, which meets regularly to assess global crises and advise on how our funding would have the greatest impact

How do the budget decisions impact on different people and places?

Some of the challenges the IDF is tackling include the following:

- In 2024, 309 million people are estimated to face acute hunger in 71 countries across the world. Food crises are driven by the interaction of underlying poverty, structural weaknesses, and economic shocks, weather extremes, and conflicts and insecurity, and have the potential to disrupt or destabilise education, health and the equitable provision of these and other basic services.

- The UN estimates that four in five countries (out of 104 studied) have suffered learning losses as a result of the ongoing impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. Without additional measures, approx. 300 million children will lack basic numeracy and literacy skills and that 84 million children and young people will be out of school by 2030.[45]

- It is estimated that 1 in 6 people experience ‘significant disability’, with 80% of these people living in developing countries. Internationally, disabled children remain disproportionately more likely to be out of school than children who are not disabled.[46]

- Globally non-communicable diseases (NCDs) are the leading cause of death and disability, killing around 41 million people each year –with 75% of deaths occurring in low- and middle-income countries. Many countries are facing a ‘double burden’ with increasing rates of NCDs coupled with ongoing high mortality from communicable disease. This is the case within the Scottish Government’s partner countries of Rwanda, Malawi and Zambia with 35-50% of deaths as a consequence of NCDs. NCDs are inextricably linked to poverty, and amongst the poorest billion, more people under 40 years old are dying from NCDs, than HIV, tuberculosis and maternal deaths combined.[47]

- Research indicates high levels of discrimination against, and social hostilities involving, religion and beliefs across the world.

- Violence against women and girls (VAWG) is a violation of women’s human rights and is widespread globally. The Global Gender Gap Index 2023 shows that Malawi had a prevalence of gender violence in women’s lifetimes of 37.5 per cent, and a child marriage rate of 26.9 per cent.[48] In the same study, in 2024 (Malawi was not represented in this study in 2024), Zambia had a prevalence of gender violence in women’s lifetimes of 28 per cent, and child marriage rate of 14.6 per cent. For Rwanda, it ranked 39 out of 146 and had a gender violence prevalence of 23 per cent.[49]

- The Global Gender Gap Index 2023 shows that Malawi ranked 110 out of 146 countries in terms of gender equality.[50] In the same study, in 2024 (Malawi was not represented in this study in 2024), Zambia is ranked 92 out of 146 countries in terms of gender equality and Rwanda is ranked 39 out of 146.[51]

- UN Security Council resolution 1325 reaffirms the important role of women in the prevention and resolution of conflicts, peace negotiations, peacebuilding, peacekeeping, humanitarian response and in post-conflict reconstruction, and stresses the importance of their equal participation and full involvement in all efforts for the maintenance and promotion of peace and security.

The Scottish budget tackles these challenges in a number of ways including the following:

- The Humanitarian Emergency Fund provides lifesaving assistance for crisis hit communities across the world, including in Sudan, Gaza and Lebanon. Gender is mainstreamed in all HEF projects, with many prioritising women, disabled people and other marginalised groups for support and featuring specific initiatives to address gender-based violence.

- The Scottish Government supports PEN-PLUS services within Malawi, Rwanda and Zambia, where marginalised populations suffer disproportionately from NCDs due to limited healthcare access, higher risk factors (e.g. hypertension and obesity), and economic strain. PEN-PLUS helps deliver essential services to manage common NCDs like hypertension, diabetes, and chronic respiratory diseases at primary healthcare settings.

- The Scottish Government’s Realising Inclusive and Safer Education programme is being delivered by Link Education International between July 2024 and March 2029, aims to remove barriers to quality education for out-of-school children with disabilities and additional support needs.

- A three-year Police Scotland Partnership Programme with Malawi and Zambia (2024-27), aims to prevent violence against women and children in Malawi and Zambia.

- The Women and Girls Fund, a multi-year programme from 2024-28 aims to provide direct funding to women and girl-led organisations in Malawi, Rwanda and Zambia to advance gender equality and the rights of women and girls.

- The Scottish Peace Programme, to be launched in January 2025, will continue the implementation of the Scottish Government’s 1325 Women in Conflict Fellowship, which equips female peace-building activists from countries affected by conflict across the Middle East, South Asia and Africa with skills in gender-sensitive conflict resolution, mediation and reconciliation.

How will the impact of the policy decisions be evaluated?

Each programme is regularly monitored and evaluated. In addition, the International Development Team engages with senior representatives of partner countries as well as with representatives of the organisations who implement programmes to discuss, monitor and evaluate impact.

The Scottish Government is increasingly participating in global forums and initiatives – through multilateral organisations such as the World Health Organisation, the UN and the World Bank – who ordinarily will lead on the evaluation of programmes to which Scottish Government is contributing.

References

1 The distribution of public service spending | Institute for Fiscal Studies

2 Full details and the underlying methodology can be found at: https://www.gov.scot/isbn/9781836910688

3 These are available at: About This Booklet – Tackling inequality: guidance on making budget decisions – gov.scot (www.gov.scot)

5 Child Poverty (Scotland) Act 2017 (legislation.gov.uk)

6 Child poverty cumulative impact assessment: update – gov.scot (www.gov.scot)

7 UK Poverty 2019/20 | Joseph Rowntree Foundation

9 Scottish Child Payment: Equality Impact Assessment – gov.scot

10 School age childcare: equality impact assessment – gov.scot

12 Child poverty – monitoring and evaluation: policy evaluation framework – gov.scot (www.gov.scot)

13 https://www.gov.scot/isbn/9781836910688

15 Examining outcomes associated with Social Security Scotland spending: an evidence synthesis – gov.scot: Further evaluation of the Five Family Payments which will explore these themes further is underway, and due to be published in summer 2025.

16 Equality Impact Assessment – Scottish Child Payment (www.gov.scot)

17 Interim Evaluation of Scottish Child Payment (www.gov.scot)

18 Best Start Foods: evaluation – gov.scot (www.gov.scot)

19 Best Start Grant: interim evaluation – gov.scot (www.gov.scot)

21 Young Carer Grant: interim evaluation – gov.scot

22 Job Start Payment: evaluation – gov.scot (www.gov.scot)

23 Devolved benefis: evaluating the policy impact – gov.scot (www.gov.scot)

25 Ending homelessness together: annual report to the Scottish Parliament, November 2024 – gov.scot

27 Scottish Government internal estimates

28 3 Fuel Poverty – Scottish House Condition Survey: 2022 Key Findings – gov.scot

29 Transport and Travel in Scotland 2022 | Transport Scotland

30 Employment support programme: equality impact assessment – gov.scot (www.gov.scot)

32 https://www.gov.scot/publications/annual-survey-of-hours-and-earnings-2022/

39 Drug-related Deaths in Scotland in 2023 | National Records of Scotland (nrscotland.gov.uk)

41 Drug-related Deaths in Scotland in 2023 | National Records of Scotland (nrscotland.gov.uk)

42 See case study for details

43 Evaluation of the 2021–2026 National Mission on Drug Deaths – Publications – Public Health Scotland

45 The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2023: Special Edition.

48 WEF_GGGR_2023.pdf (weforum.org)

49 WEF_GGGR_2024.pdf (weforum.org)

Contact

Email: ScottishBudget@gov.scot

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback