The Scottish Health Survey 2023 - volume 1: main report

This report presents results for the Scottish Health Survey 2023, providing information on the health and factors relating to health of people living in Scotland.

5 Diet and Food Insecurity

Victoria Wilson

5.1 Introduction

Poor diet is one of the leading risk factors for ill health globally[87] and dietary habits learned in childhood can influence behaviour later in life.

Non-communicable diseases (NCDs), such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes and cancer, are also referred to as chronic diseases as they often affect individuals over a long period of time. NCDs result from a number of risk factors, often in combination, including diet and obesity. The risk of such conditions can be reduced by improvements in the nutritional content of diets[88],[89].

Nutritional recommendations include the consumption of five 80g portions of fruit and vegetables per day. For children, a portion size will vary in accordance with age, body size and level of physical activity, and approximates the amount that fits into the palm of their hand[90] (see 5.1.2 for definition used in SHeS).

The Scottish Government recognise food insecurity as a lack of access to enough or appropriate food due to a lack of resources[91]. As well as mental health, food insecurity has been associated with a number of other chronic health conditions such as type 2 diabetes, obesity and heart disease[92]. Increases in the cost of living, including food prices, have placed additional economic pressure on households, widening inequalities and increasing the likelihood of turning to less healthy but cheaper foods[93],[94].

5.1.1 Policy background

Eating well is a key public health priority for Scotland. A Healthier Future: Scotland’s Diet and Healthy Weight Delivery Plan[95], published in July 2018, sets out a vision where everyone eats well, including:

- That children have the best start in life eating well.

- A food environment that supports healthier choices.

- A reduction in diet-related health inequalities.

- Funding for community projects that work to address food insecurity and develop skills to plan and prepare nutritious meals.

- Support for children facing food insecurity during the school holidays.

The Delivery Plan is underpinned by the Scottish Dietary Goals[96] and includes wide ranging actions to support healthier diets such as: Eat Well Your Way (a guide to help people plan, prepare and cook healthier food)[97] and Parent Club (a holistic support package for parents and carers which includes advice on easy, healthy meals and snacks for children)[98]. There is also a focus on efforts to address factors such as environmental cues that encourage people to make less healthy choices.The Scottish Government commitment to legislation restricting the promotion of less healthy food and drink sold to the public will be informed by the outcome of a consultation on the detail of proposed regulations which closed in May 2024[99].

Healthy Eating in Schools was published in 2021 to provide guidance for schools as they implement the statutory National Requirements for Food and Drink in Schools (Scotland) Regulations 2020. The regulations, which came into force in April 2021, are based on scientific evidence and dietary advice designed to ensure that children and young people are provided with an appropriate amount of energy and key nutriets as part of their school day to support their healthy growth and development. This includes, for example, reducing the amount of sugar that can be accessed at school.

In June 2023, the Scottish Government announced a new plan based on a ‘cash-first’ approach to tackling food insecurity. The plan, grounded in human rights, works towards ending the need for food banks in Scotland. Over three years, nine collaborative actions will be taken forward to improve the response to crisis, using a cash-first approach so that fewer people need to turn to food parcels. This includes urgent access to support, including financial during times of crisis and engaging with community, council and third sector initiatives to tackle future need by incorporating this advice and support[100].

5.1.2 Reporting on diet and food insecurity in the Scottish Health Survey

In this chapter, the following data are presented:

- children’s fruit and vegetable consumption

- food insecurity

- adult life satisfaction and mental wellbeing (WEMWBS) by food insecurity

Portion sizes for children are calculated for SHeS in the same way as for adults, with 80g equalling a portion.

Figures are reported by age, sex and area deprivation.

Diet questions for adults were not included in the survey in 2023.

The area deprivation data are presented in Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation (SIMD) quintiles. To ensure that the comparisons presented are not confounded by the different age profiles of the quintiles, the data have been age-standardised. For detailed definitions of both SIMD and age-standardisation as well as terminology used in this chapter and for further details on the data collection methods for diet and obesity, please refer to Chapter 2 of the Scottish Health Survey 2022- volume 2: technical report.

Please note that some caution should be exercised when interpreting data for 2021 within any time series data presented due to some methodological changes during the pandemic. Please see the 2022 Scottish Health Survey technical report for more information.

5.1.3 Comparability with other UK statistics

Child fruit and vegetable consumption data are collected in the National Diet and Nutrition Survey (NDNS) [101] for Scotland, Wales, England and Northern Ireland and should be fully comparable.

Food insecurity prevalence estimates are available from the UK-wide Family Resources Survey (FRS) [102] for Scotland, Wales, England and Northern Ireland and are fully comparable.

5.2 Results

Summary points

In 2023:

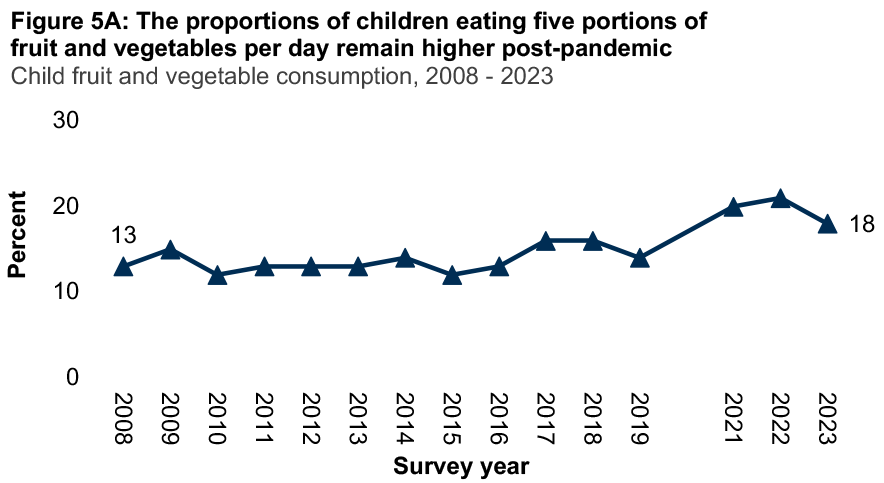

- Just under a fifth (18%) of children aged 2-15 consumed five or more portions of fruit and vegetables per day, a proportion similar to 2021 (20%) and 2022 (21%) and remaining higher than in earlier years (13% in 2008).

- Fruit and vegetable consumption was higher among children aged 2-7 (mean of 3.4 portions per day) compared with children aged 8-15 (mean of 2.8 portions per day).

- 14% of adults reported experiencing food insecurity, an increase from 9% in 2021 and the highest level since the time series began in 2017.

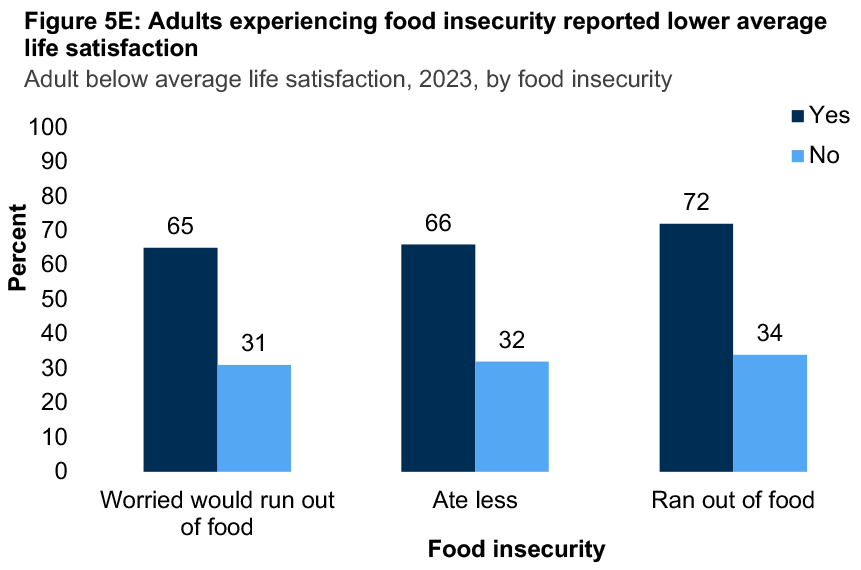

- Almost two-thirds of adults (65%) who had worried that they would run out of food in the last 12 months reported below average life satisfaction, more than double the proportion for adults who had reported that they were not worried that they would run out of food (31%).

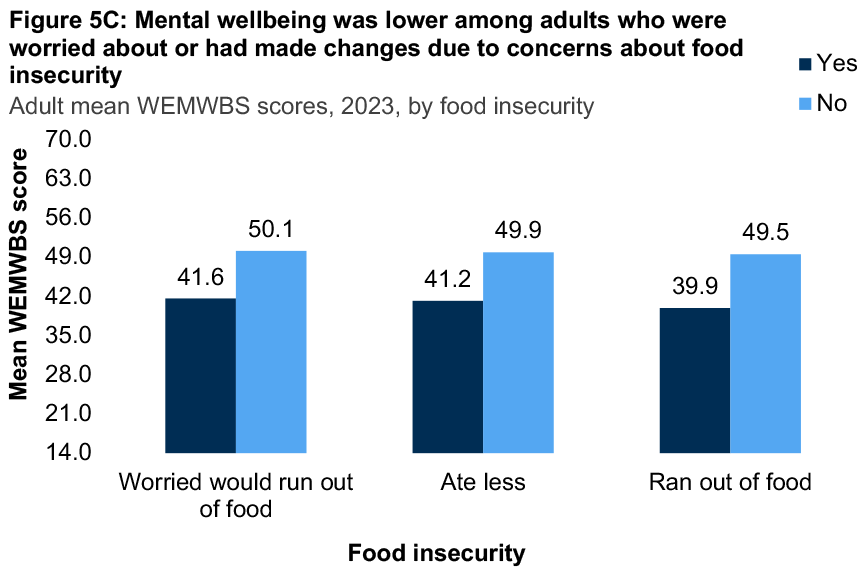

- A similar pattern was recorded for mental wellbeing, with much lower mean WEMWBS scores among those who had worried about running out of food (41.6 compared to 50.1 who had not). The mean WEMWBS score for those who had run out of food in the last 12 months due to a lack of money or other resources was 39.9 compared to a mean of 49.5 for those who had not.

5.2.1 Mean fruit and vegetable consumption among children in 2023 remained at the higher end of the range recorded since 2008

Between 2008 and 2019, mean fruit and vegetable consumption among children aged 2-15 was in the range 2.6 – 2.9 portions per day. Since 2021, this has been in range of 3.1 – 3.4 portions per day (3.1 portions in 2023).

In 2023, just under a fifth of children aged 2-15 ate five or more portions of fruit and vegetables per day (18%). The 2023 figure was similar to 2021 (20%) and 2022 (21%), remaining higher than in the early years in the time series (13% in 2008).

5.2.2 Fruit and vegetable consumption was higher among children aged 2-7 compared with those aged 8-15 in 2023 sex

Younger children were more likely to have eaten fruits and vegetables than older children in 2023, with 22% of those aged 2-7 having eaten five or more portions per day compared with 15% among children aged 8-15.

Mean consumption of fruits and vegetables was also higher in 2023 among younger children between the ages of 2-7 (mean 3.4 portions) compared with those aged 8-15 (2.8 portions).

Similar patterns were evident for both males and females. Table 5.2

5.2.3 Adult food insecurity has increased to its highest point since the start of the time series in 2017

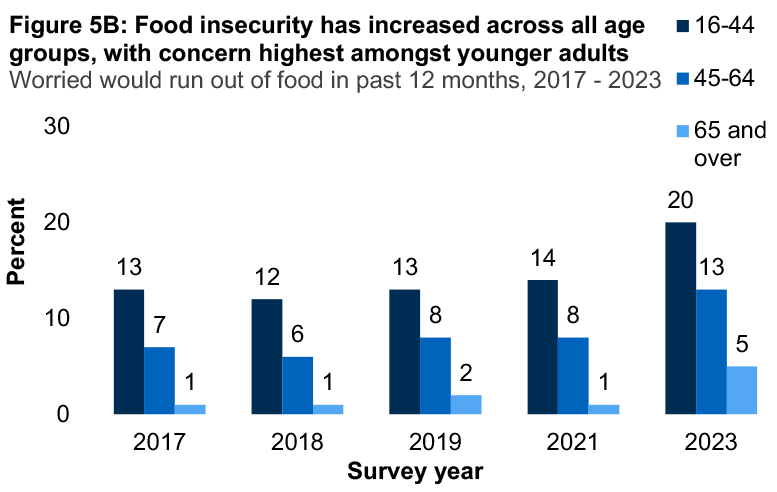

In 2023, 14% of adults worried about running out of food in the last 12 months, an increase from 8-9% between 2017 and 2021 and the highest figure in the time series.

Younger adults were more likely to experience food insecurity than older adults with 20% of those aged 16-44 having worried about running out of food compared with 5% of those aged 65 and over.

There were not significant differences between males and females experience of food insecurity.

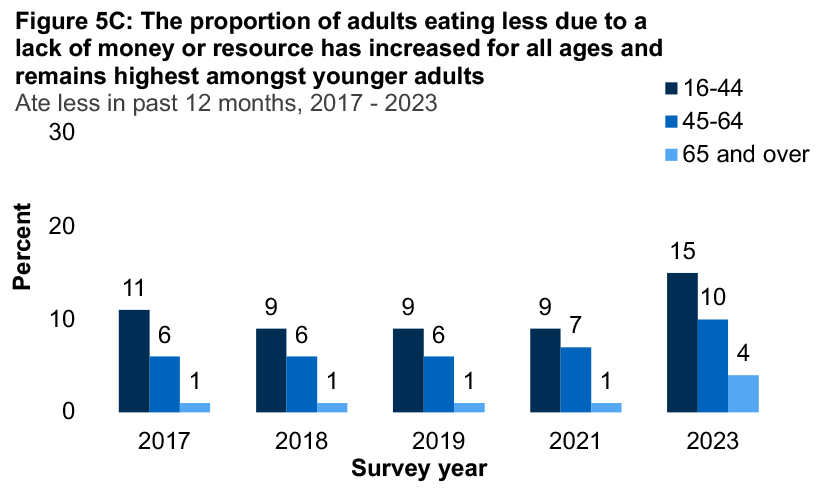

Among all adults, 11% had eaten less in the previous 12 months in 2023, which was significantly higher than the 2017 – 2021 range of 6– 7%. The same pattern as for those worrying about running out of food was seen by age, with the proportion of adults who had eaten less in the last 12 months due to a lack of money or other resources being highest among those aged 16-44 (15%) and lowest among those aged 65 and over (4%).

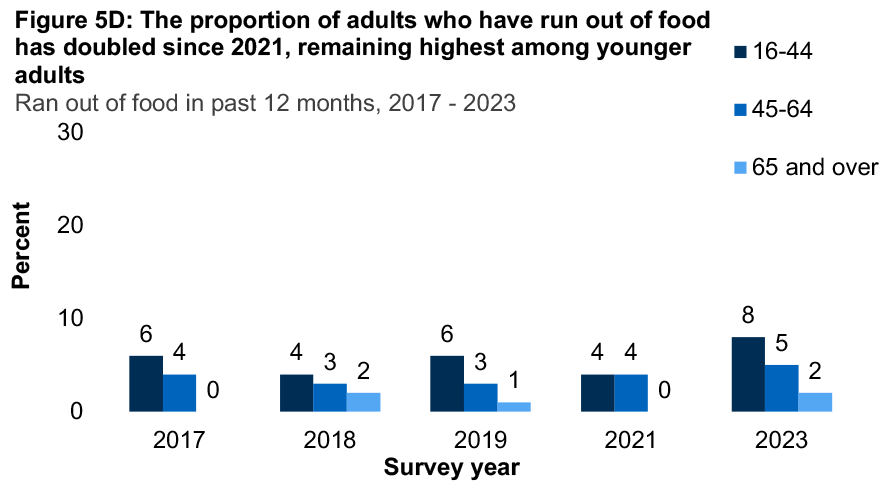

The proportion of adults who had run out for food in the previous 12 months due to a lack of money or resources in 2023 (6%) was double the rate in 2021 (3%). The proportion of adults aged 16-44 who had run out of food was higher than among those aged 65 and over in 2023 (8% and 2% respectively).

5.2.4 Adults experiencing food insecurity reported lower average life satisfaction

Two thirds of adults who had worried that they would run out of food in the last 12 months reported below average life satisfaction (65%) in 2023, more than double the proportion of adults who had reported that they were not worried that they would run out of food (31%).

The same pattern was evident for adults who had eaten less in the last 12 months due to a lack of money or other resources, with below average life satisfaction reported by 66% of adults, compared with 32% of adults who had not eaten less in 2023. Likewise, 72% of adults who reported having run out of food for this reason in 2023 reported below average life satisfaction compared with of those who had not (34%).

5.2.5 Adults who experienced food insecurity in 2023 had much lower mental wellbeing

The mean WEMWBS score for adults who had worried about running out of food in the last 12 months was 41.1 in 2023, significantly lower than the mean among those who had not worried about running out of food (50.1).

The same pattern was observed when comparing mean WEMWBS scores according to whether adults had eaten less (41.2 among those who had compared with 49.8) and/or had run out of food in the last 12 months due to a lack of money or other resources (39.9 among those who had compared with 49.5 among those who had not).

Note: WEMWBS scores range from 14 to 70. Higher scores indicate greater wellbeing.

Notes

- Some caution should be exercised when interpreting data for 2021 within any time series data presented due to some methodological changes during the pandemic. Please see the Scottish Health Survey 2022 - volume 2: technical report for more information.

- Food insecurity questions ask about food insecurity in the last 12 months because of a lack of money or other resources.

Table list

Table 5.1 Child fruit and vegetable consumption, 2008 to 2023, by sex

Table 5.2 Child fruit and vegetable consumption, 2023, by age and sex

Table 5.3 Adult food insecurity, 2017 to 2023, by age and sex

Table 5.4 Adult life satisfaction (age-standardised), 2023, by food insecurity and sex

Table 5.5 Adult WEMWBS mean scores (age-standardised), 2023, by food insecurity and sex

References and notes

1 GBD 2019 Risk Factor Collaborators (2020). Global burden of 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019, The Lancet; 396(10258): p1223-1249. Available at: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(20)30752-2/fulltext

2 See https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases

3 Peters, R, Ee, N, Peters, J, Beckett, N, Booth, A, Rockwood, K and Anstey KJ. (2019). Common risk factors for major noncommunicable disease, a systematic overview of reviews and commentary: the implied potential for targeted risk reduction, Therapeutic Advances in Chronic Disease, Vol 10, pp.1-14. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6794648/

4 See https://www.nhs.uk/live-well/eat-well/5-a-day/portion-sizes/

5 See https://www.gov.scot/publications/scottish-government-response-un-food-insecurity-poverty/pages/4/

6 National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (2023). Food Accessibility, Insecurity and Health Outcomes. Available at: https://www.nimhd.nih.gov/resources/understanding-health-disparities/food-accessibility-insecurity-and-health-outcomes.html

7 Stone, RA, Brown, A, Douglas, F, Green, MA, Hunter, E, Lonnie, M, Johnstone, AM, Hardman, CA and FIO Food Team. (2024). The impact of the cost of living crisis and food insecurity on food purchasing behaviours and food preparation practices in people living with obesity. Appetite, Vol 196. Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0195666324000564

9 A Healthier Future: Scotland’s Diet & Healthy Weight Delivery Plan, Edinburgh:

Scottish Government, (2018). Available at: http://www.gov.scot/Publications/2018/07/8833

10 See: https://www.gov.scot/publications/scottish-dietary-goals-march-2016/

11 See: https://www.eatwellyourway.scot/

12 See: https://www.parentclub.scot/topics/food-eating

13 Restricting promotions of food and drink high in fat, sugar or salt – Consultation on the detail of proposed regulations – Scottish Government consultations (2024). See: https://consult.gov.scot/population-health/restriction-promotion-of-food-and-drink-proposed/ and https://www.gov.scot/publications/restricting-promotions-food-drink-high-fat-sugar-salt-consultation-detail-proposed-regulations/

14 See: https://www.gov.scot/news/tackling-food-insecurity-2/

15 See: National Diet and Nutrition Survey - GOV.UK (www.gov.uk)

Contact

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback