The Scottish Health Survey 2023 - volume 1: main report

This report presents results for the Scottish Health Survey 2023, providing information on the health and factors relating to health of people living in Scotland.

1 Mental Health and Wellbeing

Erin Deakin

1.1 Introduction

Mental health is defined by the World Health Organisation as a state of well-being in which every individual realises their own potential, can cope with the stresses of life, can work productively, and is able to make a contribution to their community[11].

Many factors can have an impact on mental health and wellbeing including social, cultural, political, environmental and economic factors such as living and working conditions and social support[12]. These societal conditions put some groups at greater risk of poor mental health than others. Existing literature suggests that adults living in Scotland’s most deprived areas are three times as likely to die from suicide when compared to those living in Scotland’s least deprived areas and drug-related deaths are estimated to be 18 times higher in the most deprived areas[13].

Poor mental health has a considerable impact on individuals, their families and society as a whole[14]. Approximately one in four people in Scotland will face a mental health problem during their lifetime [15]. Those with a mental health condition have a higher risk of having/developing a physical illness, this being diagnosed later and record higher mortality rates[16].

Loneliness is a significant public health problem[17] which can contribute to the onset and continuation of poor mental health[18] and which is likely to be exacerbated by increases in the cost of living and the ability of some individuals to maintain connections with others[19]. Groups at increased risk of loneliness include (but are not limited to) those with poor mental and/or physical health, those living in poverty and/or with unemployment, 16-24 year olds and older adults, those with disabilities, those from LGBTQ+ or minority ethnic communities and the digitally excluded[20].

Employment status also has its repercussions for mental health. Compared to those who are employed, being unemployed or economically inactive is linked to higher rates of common mental health problems[21]. It has been estimated that around two-fifths of all work-related illness in the UK may be attributable to work-related stress[22]. Chronic stress has been associated with various physical and mental health impacts including brain structure and cognitive function, the immune system, cardiovascular disease and depression[23].

1.1.1 Policy background

In June 2023, the Scottish Government published a new Mental Health and Wellbeing Strategy jointly with the Convention of Scottish Local Authorities (COSLA). The shared vision is of a Scotland, free from stigma and inequality, where everyone fulfils their right to achieve the best mental health and wellbeing possible. It has a focus on promoting positive mental health and wellbeing, preventing mental health issues occurring or escalating and tackling underlying inequalities and providing mental health and wellbeing support and care in the right place at the right time. The Strategy is evidence-based, informed by lived experience, and underpinned by equality and human rights. It focuses on outcomes, and is driven by data and intelligence. The Strategy’s first Delivery Plan and Workforce Action Plan were published on 7 November 2023 and they describe the work that the Scottish Government and partners, will undertake over 18 months under each of the Strategy’s 10 priorities. Actions in the Plan cover a wide spectrum, with many being focused on the mental health and wellbeing of children, young people and families, from maintaining good mental wellbeing, to support in communities, to ensuring specialist services are available whenever needed[24].

1.1.2 Reporting on mental health and wellbeing in the Scottish Health Survey

In this chapter, the following data are presented:

- mental wellbeing (Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale-WEMWBS) for adults

- risk of psychiatric disorder (General Health Questionnaire 12-GHQ-12) for adults

- stress at work for adults

- loneliness for adults

- child strengths and difficulties questionnaire (SDQ)

Figures are reported by age, sex and area deprivation.

The area deprivation data are presented in Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation (SIMD) quintiles. To ensure that the comparisons presented are not confounded by the different age profiles of the quintiles, the data have been age-standardised. For a detailed description of both SIMD and age-standardisation as well as definitions of other terminology used in this chapter and for further details on the data collection methods for mental health and wellbeing and loneliness and SDQ, please refer to Chapter 2, of the Scottish Health Survey 2023 volume 2 technical report.

1.1.3 Comparability with other UK statistics

The Health Survey for England [25], the Health Survey Northern Ireland[26] and the National Survey for Wales[27] provide estimates of adults’ mental health and wellbeing prevalence in the other UK countries. The surveys are conducted separately and have different sampling methodologies, so mental health and wellbeing prevalence estimates across the surveys are only partially comparable.

The child Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) was included in the Mental Health of Children and Young People in England survey [28]. The survey has a different sampling methodology to SHeS, so child SDQ prevalence estimates across the surveys are only partially comparable. Whilst the SDQ is not asked in Wales or Northern Ireland they do collect data on child’s mental wellbeing in the Well-being of Wales Survey[29] and the Northern Ireland Youth Wellbeing Prevalence Survey[30] respectively.

1.2 Results

Summary points

In 2023:

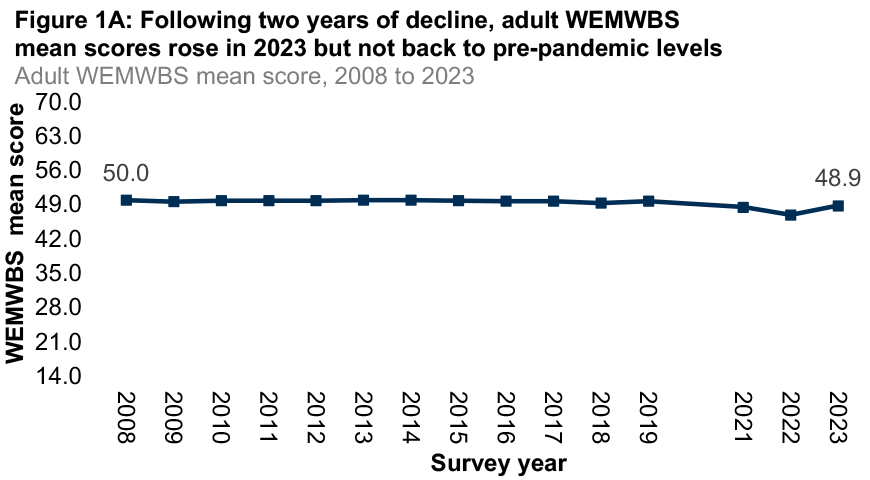

- Following two years of decline, mean WEMWBS scores for all adults increased to 48.9 in 2023 from 47.0 in 2022 and 48.6 in 2021.

- The proportion of adults with a GHQ-12 score of 4 or more (21%), indicative of a possible psychiatric disorder, returned to a similar level to 2021 (22%) following an increase to 27% in 2022.

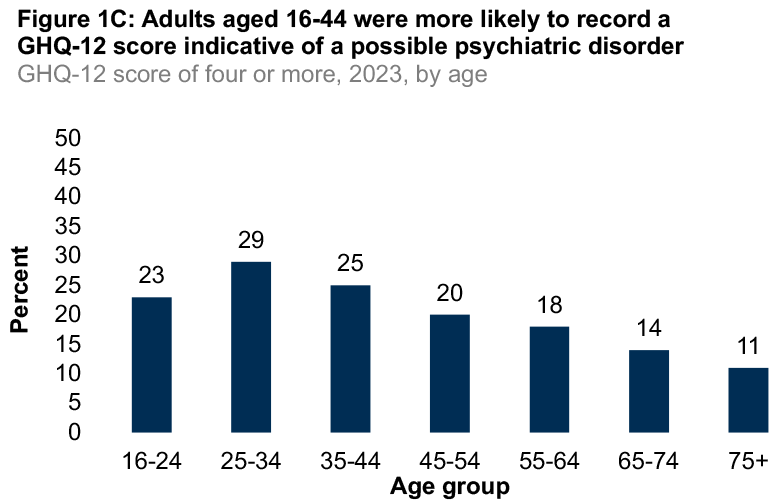

- Adults aged 16-44 were more likely to report GHQ-12 scores of 4 or more, 23%-29% compared with 11%- 14% among those aged 65 and over.

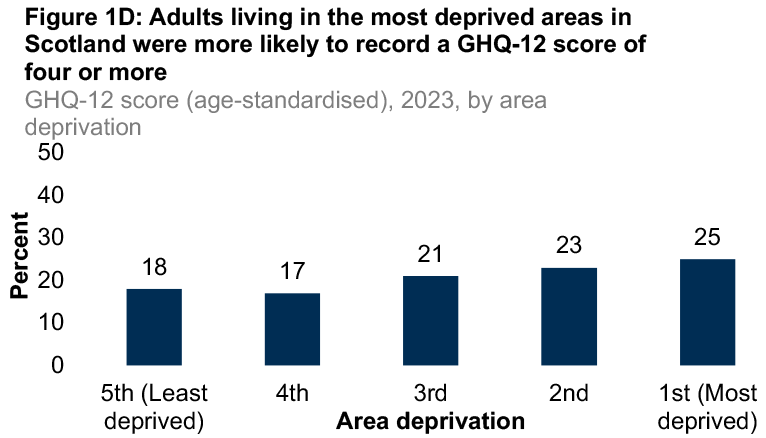

- The proportion of adults with a GHQ-12 score of 4 or more was highest among those living in the most deprived areas of Scotland (25% compared to 18% for those living in the least deprived areas).

- Adults aged 25-44 are most likely to report that their job was ‘very’ or ‘extremely stressful’ (20%-24%).

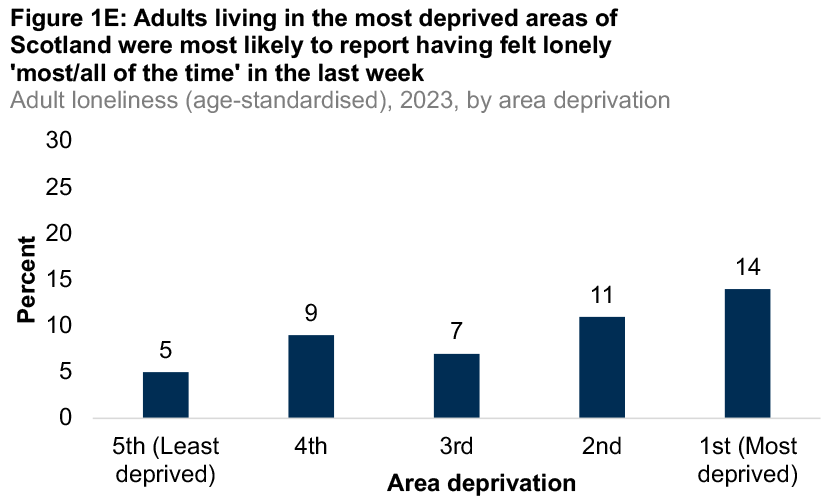

- One in ten adults (10%) reported feeling lonely ‘most’ or ‘all of the time’, with adults aged 16-24 (19%) and those living in the most deprived areas (14%) the most likely to report feeling like this in the past week.

- Male children were more likely to record ‘high/very high’ difficulties with conduct problems (13%), hyperactivity (13%) and peer problems (17%) compared with girls (8%, 8% and 11% respectively). They were also more likely to report ‘low/very low’ prosocial scores compared to females (21% and 12% respectively).

- ‘High/very high’ difficulties with peer and emotional problems were higher for older children (19% and 21% among those aged 10-12) than younger children (8% and 6% among those aged 4-5).

1.2.1 Following two years of decline, adult mental wellbeing increased in 2023

Mean WEMWBS score for all adults increased to 48.9 in 2023 from 47.0 in 2022 and 48.6 in 2021. The increase recorded in 2023 is the highest in a single year across the timeseries, however, the mean score remains below the means recorded in pre-pandemic years, which were in the range 49.4–50.0 between 2008 and 2019.

Since the time series began, males have generally recorded higher mean WEMWBS scores than females, however, this difference was not significant in 2023. Scores for both males and females have increased significantly between 2022 and 2023 (47.7 in 2022 to 49.1 in 2023 and 46.5 in 2022 to 48.9 in 2023 respectively).

Figure 1A, Table 1.1

Note: WEMWBS scores range from 14 to 70. Higher scores indicate greater wellbeing.

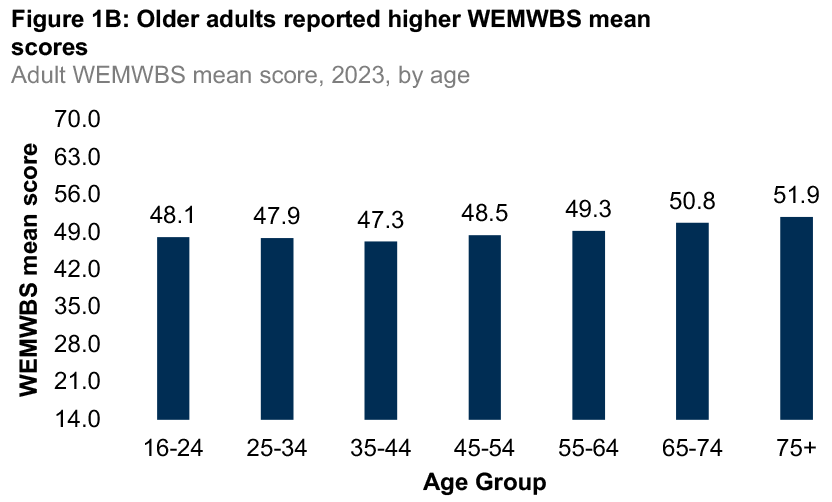

1.2.2 Older adults reported higher mental wellbeing than younger adults in 2023

Similar to previous years, older adults reported higher mental wellbeing scores than younger adults with mean WEMWBS scores in the range 49.3-50.8 for adults aged 55-74 and 51.9 for those aged 75 and over. In comparison, the mean WEMWBS scores for those aged 16 to 44 ranged from 47.3–48.1.

Figure 1B, Table 1.2

Note: WEMWBS scores range from 14 to 70. Higher scores indicate greater wellbeing.

1.2.3 The proportion of adults with a GHQ-12 score of four or more, indicative of a possible psychiatric disorder, decreased in 2023

In 2023, the proportion of adults that recorded a GHQ-12 score of 4 or more (indicative of a possible psychiatric disorder) significantly decreased compared with 2022 (21% and 27% respectively), returning to a similar level as that recorded in 2021 (22%).

However, the proportion of adults reporting a GHQ-12 score of 4 or more in 2023 remained higher than pre-pandemic years (17%-19% between 2017 and 2019 and 14%-16% between 2003 and 2016).

Consistent with previous years, the proportion of females (24%) with a GHQ-12 score of four or more was higher than males (17%). Table 1.3

1.2.4 Younger adults more likely to report GHQ-12 scores of 4 or more compared with older adults

In 2023, a larger proportion of younger adults recorded GHQ-12 scores of 4 or more, with 23%-29% of those aged 16-44 doing so compared with 11%-14% of those aged 65 and over.

Figure 1C, Table 1.4

Note: GHQ-12 scores range from 0 to 12. Scores of 4 or more indicate possible psychiatric disorder/mental ill health.

1.2.5 The proportion of adults with a GHQ-12 score of 4 or more was highest among those living in the most deprived areas of Scotland

The proportion of adults with a GHQ-12 score of 4 or more increased with deprivation in 2023, with 25% of those living in the most deprived areas of Scotland reporting a score of four or more compared with 17%-18% of those living in the two least deprived areas.

Figure 1D, Table 1.5

1.2.6 The proportion of working adults reporting that their jobs are ‘very’ or ‘extremely stressful’ remained the same as in 2021

The proportion of working adults who reported that their jobs were ‘very’ or ‘extremely stressful’ remained at 17%, the same level as in 2021. Prevalence has fluctuated between 14% and 17% since 2009.

There was no significant difference in the proportion of males and females who found their jobs ‘very’ or ‘extremely stressful’ in 2023. Table 1.6

1.2.7 Adults aged 25-44 were most likely to report that their job was ‘very’ or ‘extremely stressful’

Adults aged 25-34 and 35-44 were most likely to report finding their work ‘very/ extremely stressful’ in 2023 (24% and 20% respectively) while this proportion was lower amongst adults aged 16-24 (8%) and 65 and over (5%). Table 1.7

1.2.8 One in ten adults report feeling lonely ‘most’ or ‘all of the time’, with younger adults the most likely to report this

In 2023, 10% of adults reported having felt lonely ‘most’ or ‘all of the time’ in the week prior to being interviewed.

Younger adults were more likely to report feeling lonely compared with older adults, with 19% of those aged 16-24 reporting feeling lonely ‘most’ or ‘all of the time’ compared with 5% - 6% of those aged 65 and over. No significant variation was recorded by sex. Table 1.8

1.2.9 Adults living in the most deprived areas of Scotland were the most likely to report feeling lonely ‘most’ or ‘all of the time’

In 2023, the proportion of those living in the most deprived areas who reported feeling lonely ‘most’ or ‘all of the time’ was higher compared with those living in the least deprived areas (14% compared with 5% respectively).

Figure 1E, Table 1.9

1.2.10 Boys recorded greater difficulties than girls with conduct problems, hyperactivity, peer problems and prosocial behaviour

In 2023, eight in ten (80%) children recorded a total difficulties score on the Strength and Difficulties questionnaire (SDQ) that was close to average, with no significant differences by age or sex. The overall SDQ mean among all children was 8.8, which varied significantly by sex with males reporting higher mean SDQ scores than females (9.4 and 8.1 respectively), indicating that, on average, male children experienced higher levels of difficulties.

Differences by sex were also evident for some of the sub-categories that make up the total difficulties score. Higher proportions of males than females recorded ‘high/very high’ scores for conduct problems (13% and 8% respectively), hyperactivity (13% and 8% respectively) and peer problems (17% and 11% respectively). There were no difference in emotional symptoms by sex.

Peer and emotional problems also varied with age, with 19% of all children aged 10-12 reporting a ‘high/very high score’ for peer problems and 21% for emotional symptoms, compared to 8% and 6% of all children aged 4-5 respectively.

The SDQ also includes a section on prosocial behaviour. Differences in the proportion of children reporting a ‘low/very low’ score for prosocial behaviour were evident by sex (21% of males and 12% of females) and age (20% of children aged 4-5 and 12% of children aged 6-7). Table 1.10

Notes

- Some caution should be exercised when interpreting data for 2021 within any time series data presented due to some methodological changes during the pandemic. Please see the 2022 Scottish Health Survey technical report for more information.

- The total difficulties score is the sum of the scores for the first four domains (conduct problems, emotional symptoms, peer problems and hyperactivity).

- Age-standardised data has been presented in sections 1.2.5 and 1.2.9.

Table List

Table 1.1 Adult WEMWBS mean score, 2008 to 2023, by sex

Table 1.2 Adult WEMWBS mean score, 2023, by age and sex

Table 1.3 GHQ-12 score, 2008 to 2023, by sex

Table 1.4 GHQ-12 score, 2023, by age and sex

Table 1.5 GHQ-12 score (age-standardised), 2023, by area deprivation and sex

Table 1.6 Adult stress at work, 2009 to 2023, by sex

Table 1.7 Adult stress at work, 2023, by age and sex

Table 1.8 Adult loneliness, 2023, by age and sex

Table 1.9 Adult loneliness (age-standardised), 2023, by area deprivation and sex

Table 1.10 Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ), 2023, by age and sex

References and notes

1 Scottish Government: Population Health Directorate. Health improvement. [Online].

Available from: https://www.gov.scot/policies/health-improvement/

2 Scottish Government: Population Health Directorate. Scotland’s Public Health Priorities. [Online]. Available from: https://www.gov.scot/publications/scotlands-public-health-priorities/

3 See: http://nationalperformance.gov.scot//

4 United Nations (2015). Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

[Online]. Available from: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/21252030%20Agenda%20for%20Sustainable%20Development%20web.pdf

5 Dong W and Erens B. The 1995 Scottish Health Survey. Edinburgh: The Stationery Office. 1997. Available from: https://www.sehd.scot.nhs.uk/publications/sh5/sh5-00.htm

6 Shaw A, McMunn A and Field J. The 1998 Scottish Health Survey. Edinburgh: The Stationery Office. 2000. Available from: https://find.data.gov.scot/datasets/21894

7 Scottish Health Survey – telephone survey – August/September 2020: main report. Edinburgh, the Scottish Government. Available from: https://www.gov.scot/publications/scottish-health-survey-telephone-survey-august-september-2020-main-report/

8 Scottish Government (2021). Heart Disease Action Plan [Online]. Available at: https://www.gov.scot/publications/heart-disease-action-plan/

9 Scottish Government (2023). Stroke Improvement Plan 2023 [Online]. Available at: https://www.gov.scot/publications/stroke-improvement-plan-2023/pages/3/

10 See https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/high-blood-pressure-hypertension/

11 World Health Organisation (2024). Mental Health [online]. Available at:

https://www.who.int/health-topics/mental-health#tab=tab_1

12 World Health Organisation (2021). Comprehensive Mental Health Action Plan 2013-2030 [online]. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240031029

13 Poverty Alliance (2022). Tackling poverty for good mental health [online]. Available at: https://www.povertyalliance.org/tackling-poverty-for-good-mental-health/

14 World Health Organization (2022). World mental health report [online]. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240049338

16 Doherty, AM and Gaughran, F. (2014). The interface of physical and mental health. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, Vol 49, pp. 673-682. Available at: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00127-014-0847-7

17 A Connected Scotland: our strategy for tackling social isolation and loneliness and building stronger social connections. Edinburgh: Scottish Government (2018). Available at: https://www.gov.scot/publications/connected-scotland-strategy-tackling-social-isolation-loneliness-building-stronger-social-connections/

18 Health Scotland (2018). Social Isolation and Loneliness in Scotland: a review of prevalence and trends. [online]. Available at: http://www.healthscotland.scot/media/1712/social-isolation-and-loneliness-in-scotland-a-review-of-prevalence-and-trends.pdf

19 Social isolation and loneliness: Recovering our Connections 2023 to 2026. Edinburgh: Scottish Government (2023). Available at: https://www.gov.scot/publications/recovering-connections-2023-2026/

21 Mental Health Foundation. Poverty: statistics [online]. Available at:

22 See https://www.nhsinform.scot/healthy-living/mental-wellbeing/stress/beat-stress-at-work/

23 Mariotti, A. (2015). The effects of chronic stress on health: new insights into the molecular mechanisms of brain-body communication. Future Science OA, Vol 1(3) [online]. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5137920/

24 See https://www.gov.scot/publications/mental-health-wellbeing-delivery-plan-2023-2025/

25 See: https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/health-survey-for-england

26 See: https://www.nisra.gov.uk/statistics/find-your-survey/health-survey-northern-ireland

Contact

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback