Climate change: Scottish National Adaptation Plan 2024-2029

Sets out the actions that the Scottish Government and partners will take to respond to the impacts of climate change. This Adaptation Plan sets out actions from 2024 to 2029.

Outcome One: Nature Connects (NC)

Nature connects across our lands, settlements, coasts and seas.

“When one tugs at a single thing in nature, he finds it attached to the rest of the world.” – John Muir

Our efforts to address the risks posed by climate change, and to ensure a just transition, must have nature at their centre.

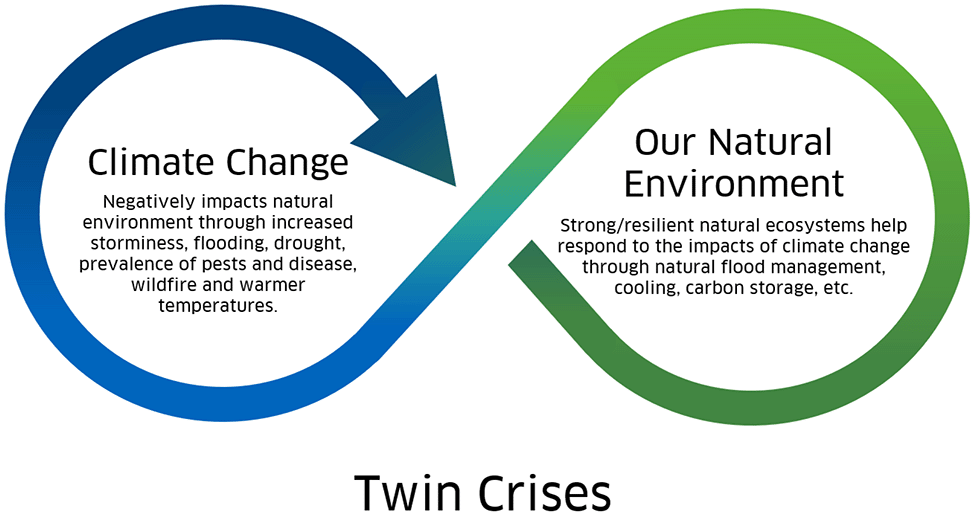

This is not only because climate change is degrading our natural environment, which must be protected and restored in its own right, and also for its value as “natural capital”[1]. But also because nature is one of the best tools we have to adapt to the changing climate and to reduce our greenhouse gas emissions (see Figure 5 below). We cannot address one without the other. Nature has a place throughout Scotland, from our rural and island communities to our towns, cities, villages and built environment. It is also goes beyond terrestrial biodiversity. Our marine environment is harshly impacted by climate change and healthy coasts and seas are essential for responding to the twin crises of climate change and biodiversity loss.

Twin Crises are interlinked and mutually reinforcing.

Climate Change:

- Negatively impacts natural environment through increased storminess, flooding, drought, prevalence of pests and disease, wildfire and warmer temperatures.

Our Natural Environment:

- Strong/resilient natural ecosystems respond to the impacts of climate change through natural flood management, cooling, carbon storage, etc.

Impact of climate change on nature

Climate change is the biggest threat to Scotland’s wildlife and habitats. Changing rainfall patterns, water scarcity, flooding, ocean warming and acidification, extreme heat and wildfire are all impacting the rate and extent of terrestrial, freshwater and marine species losses across Scotland. The negative consequences on native species, from a greater number of pests, pathogens and Invasive Non-Native Species (INNS) are already thought to be increasing.

Nature is already degrading. The 2023 State of Nature in Scotland report found that since systematic monitoring of 407 Scottish species began in 1994, the numbers of those species has declined by 15%. Some habitats and species are directly affected, but it is the interconnected nature of our ecosystems which means that climate impacts can cascade across landscapes and affect lives and livelihoods at scale.

Nature as a climate adaptation tool

Healthy, resilient, biodiverse ecosystems help us adapt to the changing climate. Strong natural environments enhance the resilience of ecosystems and, as such, support societies to adapt to climate hazards such as flooding, sea-level rise, and more frequent and intense droughts, floods, heatwaves, and wildfires.

“Nature-based solutions are actions to protect, sustainably manage, and restore natural or modified ecosystems that address societal challenges effectively and adaptively, simultaneously providing human wellbeing and biodiversity benefits” (International Union for Conservation of Nature).

The consultation on the draft Adaptation Plan found that the majority of written responses supported enhancing green spaces, restoring natural habitats such as forests and peatlands, and improving waterway management to address risks and enhance climate resilience. Both written responses and public workshops supported proactive measures by the Scottish Government, including nature-based solutions to reduce environmental degradation and promote biodiversity.

Biodiversity is essential for human life. Spending time connecting in and with nature, in green and blue spaces, is good for physical and mental health and wellbeing (Lovell et. Al, 2020). For example, green infrastructure can contribute to better mental and physical health through providing opportunities for physical activity, social interaction and relaxation. A Public Health Scotland study on access to greenspace during the COVID-19 pandemic brought together surveys which registered between 70% and 90% agreement that greenspaces benefit mental health. This was the case across income groups (PHS, 2022).

A range of physical and mental health and wellbeing co-benefits of nature-based solutions can be realised through different pathways. These include protecting health by reducing exposure to environmental harms such as air pollution; creating environments that promote healthy behaviours including outdoor play, physical activity and active travel; creating spaces for social connection building social cohesion; and supporting skills and capacity development (Marselle et. al 2021) (Public Health England, 2020). Greater health benefits are experienced by disadvantaged groups with potential to reduce inequalities (Public Health England, 2020).

Case Study: Cumbernauld Living Landscape (CLL)> - Creating Natural Connections

CLL, established in 2013, has been working to improve Cumbernauld’s green spaces for both people and wildlife with a focus on helping everyone in the community to connect with the nature on their doorstep. The most recent project delivering the CLL vision was Creating Natural Connections (CNC), which was a partnership between the Scottish Wildlife Trust, North Lanarkshire Council, Sanctuary Scotland, the James Hutton Institute and The Conservation Volunteers.

One of the key objectives of CNC was to “improve green health and wellbeing”. Through this programme, over 200 people at risk of poor mental health were able to develop skills, using nature to manage their mental health. An evaluation conducted by the James Hutton Institute on CNC found that many people expressed that being outdoors made them feel better, highlighting a range of benefits for themselves and for the communities they work with. One participant suggested that getting outdoors with a CLL walking group was directly responsible for improvements in the mental health of the young people from a support group they worked with (JHI, 2023).

Next steps: In February 2024, CLL was awarded a National Lottery Heritage Fund grant to begin a one-year development programme of Nurturing Natural Connections. During this development phase, Cumbernauld Living Landscape project staff will work with partners, local communities, groups and organisations to develop a 5-year project that will create transformational change for our green and blue spaces, while connecting people with nature and improving resilience to the changing climate.

Why focus on nature “connects”?

Connectivity is essential for functioning healthy ecosystems. It is key for the survival of animal and plant species, and crucial to ensuring genetic diversity and adaptation to climate change. Connectivity and nature networks across all landscapes help to reinforce the importance of place in adapting to climate change, encouraging people and communities to connect in and with nature. Nature Networks are a key way in which we can improve connectivity. Broadly summarised, the theory of Nature Networks involves a cycle of improving condition and biodiversity, expansion of natural areas, and then connection with other areas.

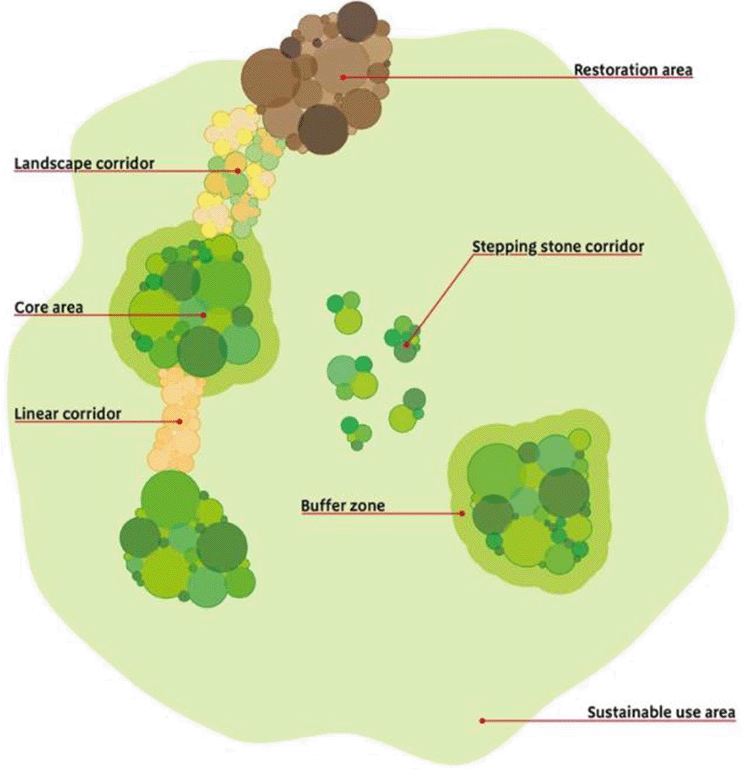

A Nature Network connects together nature-rick sites including restoration areas and other environmental projects. This will include nationally important sites contributing towards Scotland’s 30x30 target (the commitment to protect 30% of our land and seas for nature by 2030) alongside areas that are of local importance for biodiversity and people. These ecological networks as depicted in Figure 7 may be in the form of nature corridors (linear corridors directly connect areas of similar habitat, while landscape corridors are broader with a range of different biodiverse habitats) or stepping stones (indirect connections which are important for biodiversity and which allow movement between sites). They might overlap with green spaces that are also important for people, such as local conservation areas, parks, or active travel networks.

Ensuring habitats and ecosystems are healthy and resilient, alongside not introducing pests and diseases, is the best way to reduce the risks and impacts of invasive non-native species. Where connectivity is being improved between sites where there are known to be invasive non-native species, management may be needed to remove these pressures first. Further measures to reduce INNS are explored in this outcome.

Nature Networks are key pillars in the within National Planning Framework 4 (NPF4) and the Scottish Biodiversity Strategy (SBS). NatureScot has published a draft Framework for Nature Networks in Scotland, which was part of the public consultation on the first Delivery Plan for the SBS. It sets out guiding principles for implementing Nature Networks across Scotland, and will be published later this year. The Nature Connects objectives are all likely to contribute to gaining complete and functioning Nature Networks across Scotland.

Ecological connectivity is also important in the marine environment and interventions to improve the biodiversity of marine and coastal resilience are explored in this ‘Nature Connects’ outcome.

Scottish Biodiversity Strategy

In December 2022, the Scottish Government published its Scottish Biodiversity Strategy (SBS) to 2045. It set out our clear ambition for Scotland to be nature positive, with restored and regenerated biodiversity across both land and sea, by 2045. The first five-year Delivery Plan of the Scottish Biodiversity Strategy (SBS DP) is closely aligned with this Adaptation Plan, and with the Scottish Government’s principles for ensuring a just transition to net zero. Like other cross-cutting strategies and documents which help inform this Plan, the documents should be read as mutually reinforcing one another. This avoids duplication of effort but strengthens key messages and interventions which have the same goal. In ensuring high quality, healthy, climate resilient habitats across our landscapes, we can help individual species to be resilient and adaptive to our changing climate.

Any policies in this Adaptation Plan marked as “SBS DP” should be cross-referenced with the Scottish Biodiversity Strategy Delivery Plan (SBS DP) on publication, with that final document retaining authority for any final wording.

Objective: Nature-based solutions (NC1)

Nature-based solutions (NBS) are protected, enhanced and connected to enable healthier, cooler, water resilient and nature-rich places.

Scottish Government (SG) Directorate lead: ENFOR

Action to increase resilience to the impacts of climate change is delivered through nature-based solutions including street trees, parks, raingardens, green roofs, improved walking, wheeling and cycling and water ways. Water resource planning to support drought and flooding resilience, improve water quality and quantity, and protect biodiversity is a key part of improving NBS.

Compared to technology-based solutions to climate challenges, nature-based solutions are often more cost-effective, longer lasting, realise multiple benefits and contribute to the aims of a just transition:

- Reducing net emissions

- Expanding carbon sinks

- Providing habitats for biodiversity

- Benefiting human health and well-being

- Helping our society and economy adapt to climate change

- Creating more resilient and more enjoyable places to live, work and play

What is blue-green infrastructure?

‘Blue-green infrastructure’ is a subset of nature-based solutions. It is the green and blue features of natural and built environments and the connections between them that provide benefits for people and the natural environment.

- Green features include parks, woodlands, trees, play spaces, allotments, community growing spaces, outdoor sports facilities, churchyards and cemeteries, swales, hedges, verges, green roofs and gardens.

- Blue features include oceans, rivers, lochs, burns, wetlands, floodplains, canals, ponds, porous paving and sustainable urban drainage systems.

- Paths, cycleways and blue corridors such as rivers or canal paths provide connections through and between areas of green infrastructure.

Flood Resilience

The Scottish Government will promote wider uptake of blue-green infrastructure to manage surface water and drainage. This will reduce the risks associated with surface-water flooding and maximise water efficiency.

- Water, wastewater and drainage - The Water, wastewater and drainage public consultation explored how to adapt our water, sewerage and drainage services in the face of climate change. The Scottish Government is committed to undertaking a review of water industry policy, and continuing to assess how water, sewerage and drainage services can adapt to the impacts of climate change to avoid water scarcity through future legislation (See Objective PS3)

- Scottish Biodiversity Strategy Delivery Plan (SBS DP)– the draft SBS DP also lists actions aimed at increasing resilience in coastal and marine systems through NBS by reducing key pressures and safeguarding space for coastal habitat change (see Objective C6)

- Flood Resilience Strategy (FRS) - the Scottish Government’s FRS will set out what we need to do to make Scotland’s places more resilient to warmer, wetter winters and increased instances of storms and flash flooding. The FRS will encourage delivery partners to take a whole catchment approach and support interventions to increase resilience to river, coastal and surface water flooding. The FRS sets out a role for NBS in helping to create flood resilient places.

Blue-green Infrastructure Investment

Public sector and responsible private sector investment, as well as collaboration with the third sector and communities is crucial to enable delivery of blue-green infrastructure at scale. It is also vital to ensuring that local communities feel the benefits of these kinds of changes. That aim is central to our planning for a just transition in Scotland. Key commitments here include:

- Nature investment and adaptation - See Outcome B4 for integration with the Biodiversity Investment Plan, recognising that action which supports nature recovery is also key to supporting our resilience to climate change.

- SBS DP Facility for Investment Ready Nature in Scotland (FIRNS) – the Scottish Government document Green Infrastructure: Design and Placemaking provides guidance on attracting responsible private investment in Scotland’s nature. FIRNS is co-funded by The National Lottery Heritage Fund in partnership with the Scottish Government and NatureScot. Over £3.6 million has already been distributed to nature projects across Scotland to help test nature finance mechanisms, scale up conservation work and ensure the benefits are shared with local communities and opportunities for further investment will be secured in future.

- In 2024-24 eight projects spanning agricultural, fishery, woodland, and urban and rural nature restoration will receive a share of over £1 million.

- In 2023, 27 diverse projects shared over £3.6 million; split approximately, £1.8 million from public funds and another £1.8 million matched by The National Lottery Heritage Fund. The funded projects were spread across Scotland: from the Solway Firth to Shetland, Fife, across central Scotland, and the Hebrides.

- Example projects include using private finance to restore river catchments to improve water quality and reduce flood exposure, while creating community assets such as growing spaces and improved greenspace.

- SBS DP Open source platform for blue-green infrastructure – we will develop an open source platform for blue and green infrastructure and other nature assets in urban areas to support approaches to valuing and financing blue and green infrastructure.

- SBS DP Nature Restoration Fund – as part of driving increased investment in Biodiversity and Nature Restoration, the Scottish Government, supported by NatureScot will maintain and seek to increase investment in nature restoration through our £65 million Nature Restoration Fund.

- Scottish Marine Environmental Enhancement Fund (SMEEF) – managed by NatureScot, SG Marine Directorate and Crown Estate Scotland, SMEEF is an innovative nature finance mechanism that facilitates investment in marine and coastal nature enhancement in Scotland. For further detail, see Objective NC4.

Case Study: Water Environment Fund (WEF)

The Scottish Government and SEPA annually fund the WEF for direct investment in transformative placemaking projects. Over a period of 10 years, £10 million has been invested through WEF to bring nature back into the heart of Scotland’s towns and cities including Sandhills, Barrhead, Kilsyth, Shotts, Dunfermline and Leven. Further projects are currently being designed and considered for more locations across Scotland. These river restoration projects are creating attractive blue-green corridors through damaged, contaminated industrial land, as well as driving positive behaviour changes that will help Scotland adapt to the changing climate as well as create infrastructure that will support ecological and community resilience.

Levern Water Restoration

Funded partly by the WEF, a £2.8 million investment has transformed the Levern Water and the surrounding area which had previously been derelict for decades, reclaiming the space for local communities and native wildlife. Now complete - a wider, more natural river channel has been restored to the Levern Water running through Barrhead, with the ability to better absorb flooding and support for endangered species such as Atlantic salmon to recolonise restored habitat after being locked out for centuries. An attractive riverside greenspace and path network has been created for locals to enjoy in Carlibar Park, connecting to the shops and amenities in Barrhead town centre. The project was delivered by East Renfrewshire Council in partnership with SEPA, the Green Action Trust, Clyde River Foundation with support from the WEF, Scottish Government Vacant and Derelict land funding and the European Open Rivers Programme. The local school, Carlibar Primary School, was involved in monitoring the local area and invoking Citizens Science as part of the curriculum. In 2024, following the removal of two weirs, salmon have been found in the lower reaches of the Levern Water for the first time in over 100 years.

Freshwater habitats

Freshwater habitats and species are particularly vulnerable to reduced water availability and higher water temperatures due to climate change. In Scotland, this puts species such as wild Atlantic salmon and their habitats at risk.

"The Atlantic salmon is one of the most magnificent animals in the rich and vibrant tapestry of nature in Scotland. The revival of sustainable salmon populations is key for many parts of the rural economy."

The Cabinet Secretary for Rural Affairs, Land Reform and Islands (2022)

Conservation and restoration work will provide the level of ecological resilience essential to keep the level of ecosystem services provision that these habitats provide. The River Basin Management Plan for Scotland 2021-2027 (RBMP) and the Nature Conservation (Scotland) Act 2004 provide some of the tools that SEPA and NatureScot will use, on behalf of Scottish Government, to improve the quantity and quality of habitat available – supporting vulnerable freshwater plant, invertebrate, fish, bird and mammal species. Key activity includes:

- SBS DP Wild Salmon Strategy – the Strategy sets out 5 priority themes for action to protect wild salmon. A priority theme of this approach is improving the condition of rivers and giving salmon free access to cold, clean water. This will not only support salmon recovery but will benefit the diversity of life in our rivers, including the critically endangered freshwater pearl mussel, whose life cycle is inextricably linked to salmon and trout. The accompanying implementation plan, published in February 2023, lists over 60 actions to be taken over a 5-year period which will aid recovery of salmon populations, working with international and Scottish partners, including Scottish Forestry, SEPA, NatureScot, District Salmon Fishery Boards and Trusts.

- Barrier Removal - work by Scotland’s agencies, river trusts and businesses to remove obstacles in our rivers has opened up hundreds of kilometres of habitat for iconic and endangered migratory fish, including Atlantic salmon, sea trout and European eel. Projects to remove redundant structures in our rivers, such as dams and weirs which are no longer in active use, provide fish with more habitats to grow and feed and have resulted in the reestablishment of fish passages often for the first time since the industrial revolution. Access to these cooler upland streams will be of critical importance as water temperatures continue to rise as a result of climate change. Agencies such as SEPA and NatureScot, using tools such as the RBMP, will continue to find nature-based solutions capable of supporting the resilience and integrity of freshwater habitats, to the benefit of these culturally and economically important species.

Objective: Landscape scale approaches (NC2)

Landscape scale solutions are implemented for sustainable and collaborative land use, including protecting and enhancing Scotland’s soils.

SG Directorate lead: ENFOR/ARE

Working for climate resilience at a landscape scale involves land management. It involves bringing together interested actors working at a large scale, often around a catchment, estuary or other recognisable landscape unit. This is a scale at which natural systems tend to work best and where there is often most opportunity to deliver real and lasting benefits. In this way, it is possible to deliver environmental, social and economic benefits that are more difficult to achieve by managing small sites individually. Collaborating across landscapes means land managers (public, private or third sector) can achieve greater success than working in isolation.

Scotland’s soils are at increasing risk from the impacts of climate change, including flooding and drought. As soils are found across different landscapes performing multiple ecosystem functions, a landscape scale approach to improving soil condition and quality is needed.

Landscape scale interventions

Large scale, collaborative projects can improve the effectiveness and efficiency of policy delivery compared to what is achievable through individual or bilateral actions only. Commitments include:

- SBS DP Landscape restoration – by 2025, Scottish Government and NatureScot will identify, prioritise and facilitate partnership projects for six large scale landscape restoration areas with significant woodland components. By the end of 2026, we will have engaged with communities and developed deliverable action plans, funding and, where appropriate, private finance to deliver the outcomes required by 2030 and beyond.

- Scotland's third Land Use Strategy (LUS3) – LUS3 sets out policies to achieve sustainable land use. Scotland’s next Land Use Strategy (LUS4) is due for publication in 2026. Through the development of this strategy, the Scottish Government shall seek to respond more fully to the CCC’s recommendation (in its 2022 independent assessment of the previous adaptation programme) to provide an overarching ‘wrapper strategy’, to clearly outline the relationships and interactions between the multiple action plans and strategies relating to the broader environment.

- Regional Land Use Partnerships (RLUPS) – a three-year pilot programme of five regions entered its final year in 2023/24. It tested approaches to partnership governance that best suit local situations and priorities, whilst working towards the development of a bespoke Regional Land Use Framework (RLUF). Following on from this experience, the Scottish Government has committed to transitioning four of the pilot RLUPs (Cairngorms National Park, Loch Lomond and the Trossachs National Park, and South of Scotland (Dumfries and Galloway and Scottish Borders Councils) to a formal initiative. We seek to continue developing our understanding of how partnership work can help to optimise land use, in a fair and inclusive way – meeting local and national objectives and supporting Scotland’s just transition to net-zero.

- Land Use and Agriculture Just Transition Plan (LAJTP) – the LAJTP will focus on the livelihoods, skills, health, and wellbeing of those whose lives and livelihoods rely on Scotland’s land and agricultural sector. It will also focus on maintaining and supporting thriving rural, island and coastal communities. The plan will set out how wider Scottish Government policies will support our actions to tackle and adapt to climate change, as we transition to our future net zero, climate resilient economy, through:

- the creation of new or expanded economic opportunities in sectors such as nature-based solutions, natural capital investment and maintenance, green tourism, sustainable and regenerative food production, and wood products;

- an increase in health and wellbeing for both people and the environment, and;

- greater community empowerment as we look to ensure those already disadvantaged do not carry the burden, and that more benefits such as skills enhancement and employment opportunities flow to local communities.

- River Basin Management Plan for Scotland 2021-2027 (RBMP) - the third RBMP, sets out a framework for protecting and improving the benefits provided by the water environment across Scotland at the catchment level. On behalf of the Scottish Government, SEPA is working closely with public sector partners, businesses, land managers, voluntary groups and organisations towards ambitious statutory objectives at local and regional levels, to restore the natural form and function of our rivers and deliver climate adaptation on the ground including through the work of the Water Environment Fund.

- Skills - the Scottish Government’s Independent Commission (established to review learning pathways in our land-based and aquaculture sectors) reported to Scottish Ministers in January 2023, with 22 recommendations on how to attract and equip more people with the skills and knowledge needed to work in these sectors. In 2023, the Scottish Government published its response to the land-based learning review and is committed to take forward those recommendations accepted.

Case Study: River Nith Restoration

There are places where adaptation projects will need to be delivered at the landscape scale in order to effect the level of change required to meet the twin challenges of climate change and the collapse of Scotland’s natural environment. An example of what can be done when organisations and individuals work collaboratively is the River Nith Restoration Project near New Cumnock. The historical attempts to protect farmland from flood water with bunds (barriers) along the water’s edge are common to much of the River Nith and are replicated across Scotland.

The landowners engaged on this project are recognising the value of a different approach that provides space for the river, in exchange for reduced maintenance and repair costs, and improved flood management. The concept is to set back embankments from the water’s edge, restore floodplain habitats and natural river processes, and plant riparian woodland which has seen dramatic changes. Wherever the restoration work has been done, the pressure to dredge is reduced, nature has been quick to colonise and biodiversity has skyrocketed. Local communities and businesses have become more resilient to the increasing frequency and intensity of floods. Through these outcomes, the project is delivering improved climate resilience for both the environment and the community. The work has also provided opportunities for learning and education, as well as community participation in habitat restoration.

Works have been delivered by individual landowners and co-ordinated by the Tweed Forum with support from SEPA and investment from the Water Environment Fund, the Scottish Rural Development Programme and the East Ayrshire Renewable Energy Fund, totalling £2 million. Through future collaborations with the Glasgow and Southern Ayrshire Biosphere, the project aims to enlarge the new habitat network to 50 hectares. It will be extending across the River Nith valley, helping businesses and the environment adapt to the future.

Soil health

Scottish soils are at the heart of all life, and underpin much of our social and economic activity. Healthy soils are more resilient to the impacts of climate change and so lessen the effects on communities, businesses and the wider environment. Scotland’s soils provide many benefits including growing food and trees, protecting water, reducing flood risk, storing carbon and supporting biodiversity. Healthy soils also preserve our cultural and archaeological heritage, and provide a platform for buildings and roads. However, soils are at high risk of damage through compaction, erosion, and organic matter depletion – and these risks are exacerbated by the impacts of climate change, such as changing rainfall patterns and increasing temperatures. This can lead to flooding, landslides and droughts with impacts which can be difficult to reverse. Responsibility for soils spans across the Scottish Government and, recognising the cross-cutting nature of the topic, the Scottish Government will develop a route map aimed at improving soil governance and delivery in Scotland.

In 2024, the Centre of Expertise for Waters (CREW) published a study assessing the socio-economic impacts of soil degradation on Scotland’s water environment. It found that compacted soils can cost farmers £15 - £209 per hectare in extra fuel use; and the compaction of soils and sealing by infrastructure could lead to a 1% increase in flooding, with insurance claims of up to £76,000 per property flood event. It concludes that polices to protect soils from degradation create economic benefits (CREW, 2024).

There are a number of ongoing actions to protect our soils, including through peatland protection, management and restoration, sustainable forest management and the promotion of regenerative agriculture practices. This means reducing the disturbance of soils to conserve stored carbon, as well as addressing soils in poor condition. National Planning Framework 4 (NPF4) includes national planning policy on soils that sets out the intention of protecting carbon-rich soils, restoring peatlands and minimising disturbance to soils from development. This would have the policy outcomes that: valued soils are protected and restored; soils, including carbon-rich soils, are sequestering and storing carbon; and soils are healthy and provide essential ecosystem services for nature, people and our economy. Areas for progress here include:

- Strategic Research Programme – the ‘Healthy Soils’ project (2022 to 2027) will deliver evidence to maintain soil health and support the protection of soil from loss and degradation. The research, funded under the Scottish Government’s Environment Natural Resources and Agriculture Strategic Research Programme and led by the James Hutton Institute, is focusing on identifying new ways of managing soils under threat from changes in climate, land use and land management. Work underway includes the design and testing of indicators and metrics to support the monitoring of Scotland's soil health. Once completed, this work should support and inform the development of mitigation and adaptation interventions.

- Research Fellowship – through ClimateXChange, one of our Centres of Expertise, Scottish Government has employed a post-doctoral soil research expert until financial year end 2024/25 to bring together policy interests on soils across Scottish Government and externally identify targeted areas for action. These actions will be identified by March 2025 with a delivery Soil Routemap agreed and published shortly thereafter.

- Scottish Soil Framework – The 2009 Scottish Soils Framework sets out the vision for soil protection in Scotland, and formally acknowledges the important services soils provide to society. A refresh of the Scottish Soil Framework will be considered as part of the delivery Soil Routemap mentioned above.

- Engagement at UK level – once established, the Scottish Government and NatureScot will play an active role in the Four Countries Soil Policy Group. This is being set up by the Joint Nature Conservation Committee (JNCC) to support national governments and key public sector bodies to take action to improve soils. Scottish Government will also engage with research and development partners – via the UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) Land Use for Net Zero Hub (LUNZ-Hub), and the European Joint Project on the Soils UK National Hub – to ensure that all actions and policies are informed by the best available evidence.

- SBS DP – the draft Scottish Biodiversity Strategy Delivery Plan sets out a number of actions relevant to improving the resilience of Scottish soils. These are still at the proposal stage and will be finalised later in 2024, but include:

- Develop evidence-based Soil Health Indicators (SHIs) that can be considered for inclusion in Whole Farm Plans and Forest Management Plans;

- Improve information for land managers on how to assess soil erosion risks and implement measures to avoid erosion (and other impacts on soil health related to climate change), including: i) raising awareness about the impacts of extreme rainfall and drought events on soils; and ii) mapping soils that have been subject to anthropogenic degradation and are candidates for soil improvement programmes by 2027/28;

- Develop and promote clear guidance for practitioners on soil compaction and ensure that by 2030, farm and forestry machinery contractors are engaged in ensuring appropriate use of equipment, uptake of decision-making tools and training, to minimise and ultimately avoid compaction damage to soils; and

- Set up monitoring frameworks to assess change in soil health, based on evidence from the Strategic Research Programme (2022-27).

Objective: Development planning (NC3)

Development planning (including Local Development Plans and associated delivery programmes) takes current and future climate risks into account and is a key lever in enabling places to adapt.

SG Directorate lead: PARD

Adopted in 2023, National Planning Framework 4 (NPF4) sets out the Scottish Government’s long-term strategy for working towards a net-zero Scotland by 2045. The framework signals a significant change in direction in how we plan for the future of our places and communities, placing the twin crises of climate change and nature loss at the front of our thinking. NPF4 offers key priorities for ‘where’ and ‘what’ development should take place at a national level, and is combined with national planning policy on ‘how’ development planning should manage change. NPF4 forms part of the statutory development plan, along with the Local Delivery Plan applicable to the area at that time.

- Current action – the Scottish Government is working with planning authorities and other stakeholders to support the preparation of a new round of Local Development Plans (LDPs). LDPs are prepared by planning authorities and are applicable to their local area. In their preparation, planning authorities must take into account the National Planning Framework 4.

Decisions on planning applications must be made in accordance with the LDP, unless material considerations indicate otherwise. Regional Spatial Strategies (RSSs), Coastal Change Adaptation Plans (CCAPs) and Local Place Plans (LPPs) – while not part of the statutory development plan – complete the spatial framework for decision making that will support the delivery of a wide range of strategic priorities.

Delivering on all of the ambitions of NPF4 will be challenging, and needs a commitment from all sectors who have an interest in creating sustainable places. NPF4 is a comprehensive document that should be read and implemented as a whole, however this section highlights the key aspects of NPF4 policies and actions that are vital in preparing for current and future climate change. NPF’s policy intent and outcomes include the encouragement, promotion and facilitation of development that addresses the global climate emergency and nature crisis (NPF4 Policy 1), with relevant policy on climate mitigation and adaptation (NPF4 Policy 2) that seeks an outcome of our places being more resilient to climate change impacts. Additionally, action on adaptation is supported via the following NPF4 policies:

- NPF4 Policy 3 Biodiversity

- NPF3 Policy 4 Impact on Natural Environment

- NPF4 Policy 5 Soils

- NPF4 Policy 6 Protecting woodlands and enhancing nature networks

- NPF4 Policy 10 Coastal change management

- NPF4 Policy 19 Adapting to extreme temperatures

- NPF4 Policy 20 Blue-Green infrastructure

- NPF4 Policy 21 Green infrastructure for play provision

- NPF4 Policy 22 Flood and water management

Further Planning Actions

- Scottish Environment Protection Agency (SEPA) and Local Development Plans (LDPs) – SEPA has a statutory duty to cooperate in the preparation of LDPs. This includes involvement in the preparation of Evidence Reports. SEPA’s evidence is critical in planning for climate resilient places. The evidence will help the planning authority understand the implications and opportunities for areas such as future flood exposure, coastal change, the water environment, and nature networks. This information can be used to underpin the LDP spatial strategy through an infrastructure-first approach to blue and green infrastructure. This is designed to deliver multiple functions such as flood prevention, water management, nature restoration, protecting soil functionality, and bringing vacant and derelict land back into positive use for people and communities.

- Open Space Strategies – the Planning (Scotland) Act 2019 introduced a new duty on planning authorities to prepare and publish an Open Space Strategy (OSS). An OSS sets out a strategic framework of the planning authority’s policies and proposals as to the development, maintenance and use of green infrastructure in their district, including open spaces and green networks. It must contain an audit of existing open space provision, an assessment of current and future requirements, and any other matter which the planning authority considers appropriate – including areas of forestry or woodland and areas for play. Draft OSS regulations (regarding the preparation and content of OSS) were consulted on in 2021/22 and comments received will be taken into consideration when finalising the regulations. OSS can also contribute to the development of Nature Networks, where these align to the implementation of the Nature Network Framework.

- SBS DP New transport infrastructure – every new transport and active travel infrastructure project should incorporate elements of blue-green infrastructure, and seek opportunities for enhancing or expanding blue-green infrastructure, by 2030.

- Evidence reports and geospatial climate risk data – research to identify geospatial data relating to climate risks, funded by ClimateXChange, is underway. The research will map the needs of planning authorities in relation to preparation of their LDP evidence reports, and identify any barriers to accessing the necessary information.

Objective: Nature Networks (NC4)

Nature Networks across every local authority area are improving ecological connectivity and climate resilience, alongside other transformative national actions to halt biodiversity loss by 2030.

SG Directorate lead: ENFOR

As noted in the outcome introduction, Nature Networks are an effective tool for improving nature restoration, biodiversity, climate resilience and mitigating climate change, by improving ecological connectivity between habitats. Such connected ecosystems are inherently more resilient, and offer a place for nature to adapt and thrive. The creation of improved areas for nature will also help to overcome rural/urban boundaries, connect green and blue space, and promote a myriad of health and social benefits.

Nature Networks can deliver multiple positive outcomes for climate, the environment and health. However, nature-based solutions can sometimes have health trade-offs. For example, in the context of climate change, they may create habitats that are more suitable for vectors - such as mosquitos or ticks – that can transit disease to humans. The UK Health Security Agency (HSA) recommend that nature-based solutions are assessed on a case by case basis to ensure that health benefits are maximised and potential harms minimised. Tools such as NPF4 policies, the Place Standard Tool, Strategic Environmental Assessments and Health Impact Assessments can help to assess potential impacts on key populations and health determinants, within a local context. To recognise this, this chapter covers both our approach to building Nature Networks, and our response to direct climate risks from Invasive Non-Native Species (INNS) and vector borne diseases.

Case Study: The Glasgow and Clyde Valley Green Network Partnership

The Glasgow and Clyde Valley Green Network Partnership was formed in 2007 to develop the idea of a ‘Green Network’ for the Glasgow City Region. The aim was to support the long-term economic, social, and environmental prosperity of the area. The vision of the Network is to “connect all quarters of the Glasgow metropolitan region with the range and quality of greenspace that is required of a vibrant growing city in the 21st century for the benefit of people, visitors and wildlife”. (Green Cities Europe)

The Glasgow and Clyde Valley (GCV) catchment contains a wide range of diverse habitats and landscape types. A long history of intensive land use throughout the area has resulted in the loss and fragmentation of semi-natural habitats and a subsequent reduction of biodiversity. Conservation policy and practice now seek to reverse the effects of fragmentation by combining site protection and rehabilitation measures with landscape scale approaches that improve connectivity and landscape quality.

The GCV Green Network will be delivered through the ‘Blueprint’ – a strategic masterplan, which consists of (a) a Strategic Access Network (facilitating the off-road movement of people around and between communities, through Green Active Travel routes and greenspace); and (b) a Strategic Habitat Network (facilitating the movement of wildlife through the landscape). Both of these are fundamental functions of a Green Network. The key mechanisms to deliver the Blueprint include:

- Planned development (as part of planning proposals);

- Public sector programmes (enhancing publicly-owned assets);

- Infrastructure investments (combining Green Network delivery with grey infrastructure projects);

- Funding opportunities (applying for environmental funding).

The Green Network will be delivered through six key components:

- New & improved greenspace (parks, gardens, woodlands and meadows);

- Urban green infrastructure (street trees, green roofs, rain gardens and ponds);

- Greening vacant & derelict land (transformed spaces and places for wildlife);

- Community growing spaces (allotment sites, orchards and community gardens);

- Wildlife habitats (more and better-connected places for nature; Forest Research UK);

- Active travel routes (more opportunities to walk, cycle and wheel away from busy roads).

Nature Networks

SBS DP Key action on Nature Networks – the SBS DP identifies one key action to “identify, expand and enhance Nature Networks and ecological connectivity”

The five sub-policies are as follows:

- Nature Networks in all local authority areas – the Scottish Government will work with local authorities to ensure spatially defined nature networks are being implemented in every local authority area. These will provide connectivity between important places for biodiversity, deliver local priorities and contribute to strategic priorities at regional and national scales by 2030.

- Mapping of opportunities – the Scottish Government will support local authorities to undertake mapping of opportunities for creating local authority-wide nature networks. These should connect locally important areas for biodiversity, provide linkage to the 30x30 network, and address local and regional priorities for climate and nature.

- Mainstreaming – the Scottish Government will continue to incorporate and embed Nature Networks into relevant national policy frameworks, including this Adaptation Plan, National Planning Framework and others, encouraging Nature Network implementation via local and regional decision-making processes, following the Nature Network Framework.

- Nature Network Toolbox – NatureScot has developed a Nature Network toolbox containing resources such as guidance, case studies, and mapping tools, which will support local authorities and other land managers in delivering, and contributing to, Nature Networks. The final Nature Network Framework will be published in 2024.

Case Study: Edinburgh's Strategic Green Blue Network - Edinburgh Living Landscapes

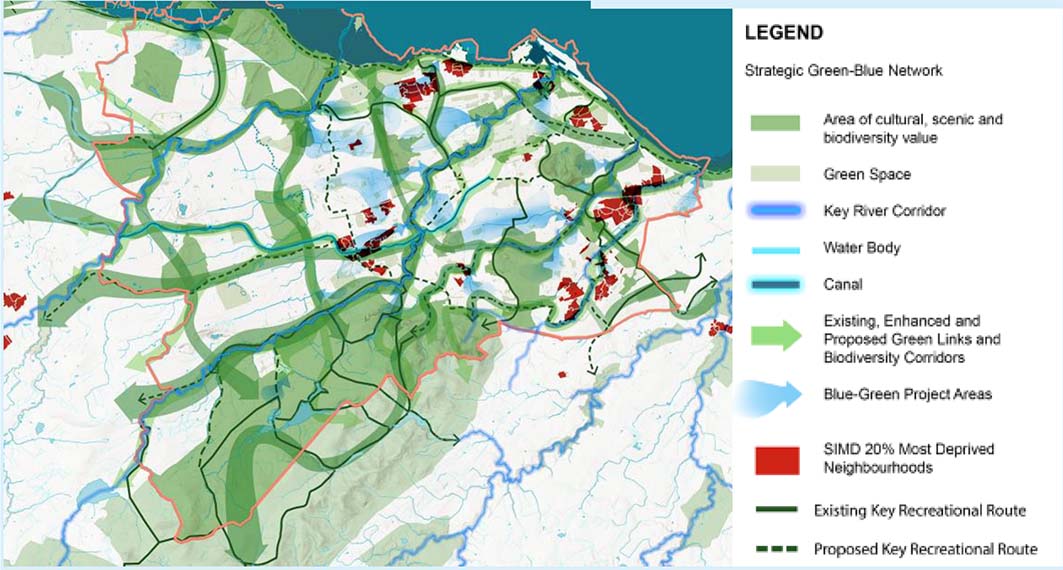

Edinburgh’s Strategic Green Blue Network aims to deliver a network of beautiful, biodiverse, connected places that are climate resilient and help improve flood resilience and regulate extreme temperatures. AtkinsRealis has undertaken work on behalf of the City of Edinburgh Council to develop the strategic network, which first appeared in the Council’s Proposed City Plan 2030 (the next Local Development Plan). It helped to support the strategy of the City Plan and to inform its Green Blue Network proposals. AtkinsRealis have subsequently refined this work, with a view to this feeding into other documents, such as future iterations of the Edinburgh Design Guidance.

Figure 10 shows the overall strategic Green Blue Network, including areas and routes important for recreation, biodiversity and water management. It also shows how the network serves Edinburgh’s most deprived areas. Although the mapping identified the key strategic components, it should be recognized that green-blue networks exist at a local scale also.

This map is supported by more detailed maps focusing specifically on the issues of biodiversity, water management and recreation. Their key elements are brought together to create the strategic, combined map.

Green Blue Neighbourhoods - The first Green Blue Neighbourhood to be taken forward is the Drylaw, Craigleith and Inverleith area of Edinburgh. Flood modelling and more detailed townscape studies have built on green blue network information. This has allowed a list of projects within this area to be prioritised. This is now being taken forward by a multi-disciplinary design team.

This neighbourhood work is known as ‘Climate Ready Edinburgh’ and, along with Edinburgh’s Green Blue Network, won the ‘Excellence in climate, environment, and social outcomes’ class, in the Landscape Institute Awards 2023.

Invasive Non-Native Species (INNS)

Invasive Non-Native Species (INNS) are continuing to establish in Scotland at unprecedented rates. INNS are considered amongst the top four global threats to biodiversity (Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services, 2019). In many cases INNS outcompete native species, disrupt ecosystem function and introduce novel pathogens and diseases. Whilst the transport and introduction of INNS is facilitated mainly by indirect economic drivers, there are also direct drivers which facilitate the establishment and spread of invasive alien species. In particular, this includes land- and sea-use change, and climate change. Fragmented and disturbed ecosystems are more vulnerable to invasive alien species, and climate change will increase the opportunities for INNS to become established in new areas.

The impacts of INNS can also amplify the impacts of climate change. For example, invasive plants growing on riverbanks die back in winter, making the banks more vulnerable to flood erosion. The magnitude of the future threat from INNS is difficult to predict, because of complex interactions between the drivers of change in nature. Outcomes can be improved by integrating INNS prevention and control into actions aimed at enhancing ecosystem function and resilience – such as through nature restoration and Nature Networks. Long-term monitoring of restoration sites is necessary to ensure early detection of INNS, so that management actions can be taken at an early stage.

Progress will be delivered through:

- SBS DP Scottish Plan for INNS – the Scottish Government will develop and implement a Scottish Plan for INNS surveillance, prevention and control, and secure wider support measures to enable effective INNS management. In partnership with agencies, environment Non-Governmental Organisations (eNGOs) and other stakeholders, both in Scotland and the United Kingdom, we aim to reduce the rate of establishment of known or potential INNS by at least 50% by 2030 compared to 2020 level. We also aim to detect priority INNS through increased inspections and vigilance of citizen scientists, ensuring they are eradicated or contained before they become established and spread.

- SBS DP Priority sites – we will develop and implement a pipeline of strategic INNS projects in the terrestrial environment to coordinate the control of priority INNS at scale, with the aim of eliminating or reducing the impacts of INNS in at least 30% of priority sites by 2030.

- SBS DP Public awareness and biosecurity – we will raise public awareness of the impacts of INNS. By 2030, we will also embed INNS biosecurity practice across those industries and recreational activities linked to the most important pathways of introduction and spread.

- SBS DP Scottish Plan for INNS (Marine) - for the marine environment, the Scottish Plan for INNS will include actions which will prevent, detect and control marine INNS, thereby protecting native marine species and habitats, allowing them to better adapt to the additional pressure of climate change. We will:

- Develop best practice guidelines and a voluntary code of conduct for INNS biosecurity, suitable for supporting marine habitat restoration by 2026. Guidelines will ensure that processes and actions carried out during restoration activities do not introduce marine INNS, ensuring resilience.

- Complete feasibility studies for management of island INNS by 2026. Where appropriate, develop and implement a rolling programme of island INNS management thereafter, focussed on the targeted removal of predators impacting on nesting seabirds.

- At the UK level, Angling and Boating Pathway Action Plans have been developed with Scottish input. The Scottish Angling Pathway Action Plan has been developed to engage directly with targeted stakeholders and manage additional pathways of INNS introduction and spread. Programmes are also underway to develop monitoring tools and methods in the marine environment, utilising partnership approaches, that allows a better understanding of marine INNS.

Vector borne disease

Related to INNS management, are efforts to manage the risks posed by vector borne diseases. A vector borne disease is a human illness caused by parasites, viruses and bacteria that are transmitted by vectors like mosquitos or ticks. Climate change is already affecting vector-borne disease transmission and spread, and its impacts are likely to worsen. CCRA Summary for Scotland states that:

“Lyme disease cases may increase with climate change due to an extended transmission season due to warmer weather and increases in person-tick contact, although non-climate drivers such as agriculture, land use, tourism and wild animal populations are also dominant influences. Scotland has more reported cases of Lyme disease compared to other parts of the UK, due to higher humidity and high rates of outdoor tourism, both of which are likely to increase with climate change.” (CCC, 2021)

Scottish Government will continue to work with partners to provide vector-borne disease surveillance, risk assessment, incident management and public health and veterinary advice:

- NHS Guidance – NHS inform will continue to provide public advice and guidance on avoiding bugs outdoors, which includes avoiding ticks.

- Lyme Disease Awareness – the Scottish Government will work with stakeholders to carry out proactive awareness raising campaigns during Lyme Disease awareness month (May) and during the summer months when people are more likely to be outdoors.

- Lyme Disease Testing - the Scottish Lyme Disease and Tick-borne Infections Reference Laboratory (SLDTRL) provides testing for tick borne infections, as well as technical and clinical advice to healthcare staff. In collaboration with Public Health Scotland (PHS), SLDTRL provides epidemiological data on Lyme disease in Scotland, and maintains close links with the UKHSA Rare and Imported Pathogens Laboratory (RIPL). Scottish Government and PHS will work with RIPL to ensure it offers comprehensive testing.

- Research into impact of warmer temperatures on tick populations – work on tick ecology is helping to identify those species that will arrive and/or increase as Scotland’s climate gets warmer. Understanding the tick population allows risk assessment for the appearance of tick-borne diseases not previously seen in Scotland.

- Veterinary Advisory Service – the Scottish Government will continue to fund the Veterinary Advisory Service, to help practicing vets to (i) identify, treat and prevent tick- borne disease in animals; (ii) conduct surveillance of Schmallenberg virus, a disease of ruminants that is spread via biting midges.

To better understand and address climate-driven vector borne disease risks over the period of this Adaptation Plan, action includes:

- Risk mapping – PHS will work with Scottish Government and other stakeholders to map the risk of emergent vector-borne disease due to climate change, in order to anticipate future changes to this risk.

- Research on enhanced surveillance – PHS and Scottish Government will scope what enhanced surveillance could look like, and link in with research projects such as the University of Glasgow Mosquito Scotland Project to fill considerable knowledge gaps on the size, distribution, seasonality, and presence/absence/potential of various vector species in Scotland, with impacts on both human and animal health.

- Enhanced surveillance – we will explore opportunities for utilising whole genome sequencing data to enhance vector borne disease surveillance programmes.

- Contingency planning – the Scottish Government and our partners will review vector borne disease contingency plans in England. We will scope out their adoption in Scotland, with appropriate modifications, including communication and planning with operational partners.

- Horizon scanning – the Scottish Government and our partners will continue to horizon-scan for vector borne diseases of livestock, such as Blue Tongue Virus, that are endemic in warmer parts of Europe and spread northwards when climatic conditions allow.

Objective: Marine ecosystems and the blue economy (NC5)

Evidence-informed planning and management improves ecosystem health, values our marine environment and supports our Blue Economy.

SG Directorate lead: Marine

Scotland’s seas and coastline are famous across the world, and are home to some of our most beautiful plants, animals and marine life. The biodiversity of our marine and coastal environment is crucial to supporting both thriving ecosystems and local economies, and it must be resilient to adapt to the impacts of climate change. Our seas are also vital in helping to mitigate the worst impacts of climate change, but are at risk of losing their ability to regulate climate if we do not protect them. This objective will set out action focused on marine planning, coastal planning, habitat restoration, and biodiversity. This includes further research and evidence gathering, in order to ensure that management of our coasts and seas is based on evidence. Fisheries and aquaculture will be discussed further in the ‘Economy, Business and Industry’ outcome.

The risks to our marine and coastal environments from climate change are stark and accelerating. Our sea levels are rising and this is threatening our coastline, with erosion affecting key communities and habitats. Our coastlines are threatened by coastal erosion perpetuated by rising sea levels. Our marine environment is threatened by ocean warming and acidification and the increased prevalence of pests, diseases and INNS. For example:

- Globally, by 2021, the ocean had absorbed around 90% of the heat generated by rising greenhouse gas emissions trapped in the Earth’s system and has taken in 30% of carbon emissions. This has caused significant changes impacting marine biodiversity. (UNFCCC, 2021)

- UK seas show an overall warming trend. Over the past 30 years, warming has been most pronounced to the north of Scotland and in the North Sea, with sea-surface temperature increasing by up to 0.24°C per decade. (MCCIP 2020 Report Card)

- The North Atlantic contains more anthropogenic CO2 than any other ocean basin, and ocean surface measurements between 1995 and 2013 reveal a pH decline (increasing acidity) of 0.0013 units per year. (MCCIP 2020 Report Card)

- Whichever pathway our warming climate follows, we are locked into sea level rise in Scotland beyond 2100. (Dynamic Coast 2, 2021)

- Estimates suggest that between £0.8 billion and £1.2 billion of coastal assets in Scotland may be at risk of erosion by 2050. (Dynamic Coast, 2021)

- Together, the cumulative impact of different climate stressors, such as oxygen depletion and ocean warming, will result in future changes in the viable habitat for a number of marine species. This may cause range shifts and or a decline in species population. (Scotland's Marine Assessment, 2020)

As an example of a species at risk: Atlantic puffins are threatened by climate change for a number of reasons, including the availability of their main source of food, sand eels, being very sensitive to ocean warming (Scottish Government, 2023). The British Trust for Ornithologists (BTO) projects a decline of puffin numbers across Britain and Ireland of nearly 90% by 2050 (BTO, 2021).

Thriving, nature-rich marine and coastal ecosystems can help reduce the negative impacts of climate change and act as powerful carbon stores as well as contributing to local, national and global economies (as set out in the ‘Economy, Business and Industry Outcome).

Marine Planning

- National Marine Plan – the National Marine Plan (adopted in 2015) sets out high-level and sector- specific objectives, including on climate change mitigation and adaptation (as required under the Marine (Scotland) Act 2010) and provides a contextual framing around climate change mitigation and adaptation to guide authorisation, licensing, and enforcement decisions for each marine sector. The requirements for monitoring the National Marine Plan are set out in the National Marine Plan – Monitoring and Reporting (2016).

- National Marine Plan 2 – a new National Marine Plan 2 (NMP2) is under development and the proposed timing for its adoption is by Summer 2027. It aims to help tackle the twin climate and biodiversity crises and support our net zero ambition, by providing a clear decision-making framework to support the management of marine space. The NMP2 will set out specific objectives and associated policies relating to climate change mitigation and adaptation, as required under the Marine (Scotland) Act 2010. It will act as a key delivery mechanism for Scotland’s Blue Economy Vision, seeking to strengthen holistic consideration of economy, society, environment and climate mitigation and adaptation in marine decisions. The new NMP2 will also set out an updated monitoring and evaluation framework to better support adaptive management.

- Regional Marine Plans – several Regional Marine Plans are under development, which will set out locally-specific planning policies. These will guide decision-making in Scottish marine regions, in conformity with National marine planning policies and objectives (including those on climate change mitigation and adaptation). Once adopted, the plans will support coastal community decision-making to deliver multiple local-scale benefits, including adaptation and mitigation of coastal erosion and flood risk, and protection of blue carbon habitats.

- Monitoring and assessment of climate change impacts in Scottish seas – the Marine Directorate will continue to provide the scientific evidence and monitoring data to inform adaptation policy in the marine and freshwater environment. Existing programmes monitoring the environment and ecosystems (such as the Scottish Coastal Observatory), and those monitoring fish and shellfish populations, have already documented the impacts of climate change. Such programmes underpin the high quality evidence and scientific consensus provided by national and international assessments, for example the Climate Change Risk Assessment, the Marine Climate Change Impacts Partnership and the Oslo-Paris Commission.

- Climate Vulnerability Assessment (CVA) - an initial review of CVA methodologies was funded through the ClimateXChange. Building on this work, the Marine Directorate will scope options to deliver an in-depth climate vulnerability assessment of the marine environment and all human related activities, including to identify key species and sectors that are more or less vulnerable to climate change.

Biodiversity and Habitat Restoration

- SBS DP Scottish Marine Environmental Enhancement Fund (SMEEF) – SMEEF was launched in May 2022 to invest in marine and coastal restoration throughout Scotland. The fund is hosted by NatureScot, with Scottish Government Marine Directorate and Crown Estate Scotland as Steering Group partners. It has enabled private and public investment to support the health and biodiversity of Scotland’s seas through habitat and restoration projects. Over the duration of SNAP3, SMEEF will continue to seek to increase investment and fund projects that recover, restore or enhance the health of marine and coastal habitats, including work to build resilience and adaptation to climate change impacts.

- To date, SMEEF has secured and distributed £3.8 million, with a mix of public and private investment, into 54 restoration and enhancement projects across Scottish coasts and seas. These projects support climate adaptation by enhancing recovery of marine species and habitats, and building ecological resilience to the impacts of climate change as well as improving social and economic resilience.

- SMEEF has announced an additional £2.1 million for seagrass restoration and is anticipating to add circa £2.5 million to its seabird resilience fund over the next 5 years.

- SBS DP Marine Protected Areas (MPA) - Scotland has some of the most beautiful and diverse marine ecosystems in the world. Marine Directorate in Scottish Government is committed to protecting and enhancing these amazing ecosystems to ensure they are safeguarded for future generations to enjoy. Protected areas are used to ensure protection of some of the most vulnerable species and habitats. The Scottish MPA network includes sites for nature conservation, and for protecting biodiversity, demonstrating sustainable management, and protecting our heritage. In total, the network covers approximately 37% of our seas. We are delivering and planning a range of actions to ensure that the Scottish MPA network is well managed. To do this Scottish Government will:

- Assess the network of marine protected areas in respect of the resilience of marine biodiversity to climate change, based on a regional assessment by the OSPAR commission, by 2026;

- Introduce fisheries closures to protect Vulnerable Marine Ecosystems in offshore waters between 400-800 metres depth, by 2027;

- Develop and implement an adaptive management framework for the MPA network, by 2028;

- Put in place fisheries management measures for those sites in the MPA network that require them, by 2025, increasing the level of protection to support the recovery and resilience of Scotland’s seas;

- Deliver further fisheries management measures for priority marine features (identified as most at risk from bottom-contacting mobile fishing gear outwith MPAs), by 2025.

- SBS DP Marine nature enhancement – in the next 2 years, we will develop a marine restoration plan for 2026-45, including prioritising marine habitats and locations suitable for restoration. This supports adaptation by contributing to the recovery of marine habitats and species, restoring ecosystem function, and enhancing biodiversity.

- SBS DP Safeguarding marine biodiversity – by 2027, we will work with stakeholders to complete a review of opportunities for increasing community participation in safeguarding marine biodiversity.

- SBS DP Seabird Conservation Strategy – by 2025, we will develop and publish a Scottish Seabird Conservation Strategy which will identify actions to conserve and increase the resilience of seabird populations.

- SBS DP UK Dolphin and Porpoise Conservation Strategy – by 2025, we will publish the UK Dolphin and Porpoise Conservation Strategy, and begin delivery of actions relevant to Scotland to conserve and manage pressures acting on these species.

- SBS DP Seals – by 2026, we will review the approach to and locations of designated seal haul-out sites in relation to the protection of seals.

Objective: Natural Carbon Stores and Sinks (NC6)

Resilient natural carbon stores and sinks (such as peatland, forests and blue carbon) are supporting Scotland's net zero pathway, alongside timber production, biodiversity gains, flood resilience and the priorities of local communities.

SG Directorate lead: ENFOR/Marine/ARE

Scotland’s natural carbon stores can be broadly categorised into peatland, forestry and woodland, and blue carbon habitats, such as saltmarsh and seabed sedimentary carbon. Protecting, managing and restoring our natural carbon stores is crucial as part of our just transition to net zero – both for their carbon sequestration and storage potential, and for their multiple co-benefits such as flood resilience and improved biodiversity.

This objective is split into the following sub-themes:

- Peatlands

- Forestry

- Blue Carbon

- Carbon in agricultural soils

Peatlands

Peatlands cover over two million hectares (or 25%) of Scotland and are of national and global significance. 60% of all UK peatlands are found in Scotland, and our blanket bog represents around 10% of the global total. In good condition, peatlands provide multiple co-benefits: capturing and storing carbon, supporting nature, reducing flood risk, improving water quality, and providing places that can support physical and mental wellbeing.

However, roughly three-quarters of our peatlands are degraded through drainage, extraction, overgrazing, burning, afforestation and development. Degraded peat offers fewer benefits and emits carbon, now accounting for around 15% of Scotland’s total net emissions and thus worsening the climate emergency.

Protecting, managing and restoring Scotland’s peatlands – through rewetting and other techniques – enhances the resilience of these ecosystems. Strong, protected, biodiverse ecosystems also help people adapt to climate change by providing nature-based solutions to climate-related risks.

Peatland restoration is also a key plank of Scotland’s just transition to net zero, supporting Scotland’s rural economy by creating economic opportunities and good green jobs. Our significant investment in peatland protection, management and restoration over the coming 10 years will support small and medium size businesses that deliver restoration works, often in rural areas, as well as the ancillary services that support the industry locally. It will also provide economic opportunities for land owners and land managers, farmers and crofters, and third sector bodies.

Maximising peatlands’ dual role – as a nature-based solution for both mitigating and adapting to the linked climate and nature emergencies – underpins our commitment to and investment in their condition. We will take the following action:

- Peatland restoration - the Scottish Government has committed £250 million over 10 years to restore 250,000 hectares of degraded peatlands by 2030. We estimate that approximately 75,000 hectares have been restored to date, including more than 10,000 hectares in 2023-24 alone – the highest area in a single year. Restoration is achieved through a range of techniques including drain blocking and bare peat restoration on upland blanket bogs (Peatland Action Technical Compendium). Working with our peatland restoration delivery partners (NatureScot, Forestry and Land Scotland, Loch Lomond and the Trossachs National Park, Cairngorms National Park, Scottish Water) we will continue to grow delivery capacity and upscale annual rates of restoration towards our current target. We will continue our work to grow responsible private investment in support of this. We will increasingly use scientific evidence and monitoring data to inform where to target investment in restoration, in order to maximise the multiple adaptation benefits peatlands provide for nature and people.

- SBS DP Peatland monitoring – by 2027, NatureScot will develop a national peatland monitoring framework that incorporates on-site and remotely sensed assessments of biodiversity indicators, climate resilience and associated functions within the wider landscape, hydrological and ecological network contexts.

- Horticultural peat sale ban – in our 2021-22 Programme for Government, the Scottish Government committed to taking forward work to develop and consult on a ban on the sale of peat-related gardening products, as part of our commitment to phase out the use of peat in horticulture. The results of our consultation on ‘Ending the Sale of Peat in Scotland’ (2023) showed that most hobby gardeners (76%) and professional horticulturalists (58%) supported a peat sales ban. During the remainder of 2024, ongoing stakeholder engagement will help shape the scope and timing of a ban. This ban aims to be ambitious and realistic, tailored to Scotland's specific needs, and designed to avoid unacceptable impacts on non-horticultural users of peat.

- Peatland protection and management - alongside restoration and our peat sales ban, Scottish Government will continue to develop a range of other measures, incentives and regulatory approaches to drive responsible stewardship of our peatlands. These include:

- From 2025, new conditions for peatlands and wetlands will be implemented under the Good Agricultural and Environmental Condition (GAEC) 6, to protect vital carbon stores, as part of the changes to agricultural support in Scotland.

- In addition, we are investigating how optimal grazing levels by both wild and farmed herbivores, combined with partial rewetting of peat and peaty soils, could contribute to further emissions reduction.

- We have also established an expert group to advise the government and develop the guidance and tools needed to inform decisions on windfarm development on peat.

- We will continue to explore ways in which fiscal policies can support improved land management outcomes, including the restoration of peatlands. This exploration will include consideration of options for a carbon land tax.

- Muirburn and moorland management – the management of upland moor areas for grouse shooting and livestock grazing can include the use of muirburn, which provides new vegetation growth for grouse and livestock to eat. Muirburn undertaken on peatlands can have an adverse impact on carbon sequestration. To address this, the Scottish Government introduced the Wildlife Management and Muirburn (Scotland) Act 2024, the legislation provides vital increased protection for our peatlands by introducing a licensing scheme for muirburn, and bans muirburn on peatland unless for a limited purpose under licence. The licensing scheme will ensure that muirburn is being undertaken in an environmentally sustainable manner.

- SEPA Land-use planning - SEPA seek to protect and improve carbon rich soils including peatland through its land use planning role. Due to their multiple co- benefits, it is therefore important that carbon rich soils are included in the preparation of blue and green infrastructure audits and/or strategies. They should also be included when identifying nature networks in Local Development Plans, to inform spatial strategies of protection and restoration opportunities.

Forestry and Woodland

Woodland and forest covers more than 1.49 million hectares in Scotland (about 19% of our total land area) and around one half (51%) of the total UK forest carbon stock in 2020 is in Scotland (2.0 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent) (Forestry Statistics, 2023). Forests are one of the best tools we have to sequester carbon released into the atmosphere. Scotland’s forests currently sequester 7.5Mt CO2 – which is equivalent to around 14% of Scotland's greenhouse gas emissions in 2022. In addition, well-designed forests, managed in line with the principles of sustainable forest management (as outlined in the UK Forest Standard) provide multiple benefits to society. These benefits include rich biodiversity, a green economy supporting rural jobs, timber products that can substitute for materials that have higher emissions and cannot be easily reused or recycled, healthy and stable soils, improved air and water quality, flood mitigation, shade and shelter that mitigates against temperature extremes, beautiful landscapes that support a diverse tourism economy, increased health and well-being, and places to support rich educational experiences.

Scotland’s Forestry Strategy (SFS) identifies climate change as a key strategic driver and sets out a vision where by 2070 “Scotland’s forests and woodlands will be a more resilient adaptable resource, with greater natural capital value, that supports a strong economy, a thriving environment, and healthy and flourishing communities”.

In addition to the action below, see further policy on the resilience of the forestry sector under Objective B2.

- UK Forestry Standard - UK Forestry Standard (UKFS), the UK technical standard for sustainable forest management underpins all Forestry Grant Scheme (FGS) and Felling Permission approvals, and all Forestry Environmental Impact Assessment determinations. Scottish Forestry are supporting the implementation of the updated UKFS (version 5), including training. The updated Standard was reviewed and revised with stakeholders to ensure, amongst other things, that compliance with the Standard increases the resilience of the forest resource. Scottish Forestry approvals will require compliance with the updated Standard from 1 October 2024.

- Woodland creation – Scottish Forestry is committed to reaching woodland creation targets set by the Scottish Government of 18,000 hectares of new woodland annually, increasing forestry’s contribution to climate change mitigation.

- Right Tree in the Right Place (RTRP) – the RTRP guidance contains information related to the preparation of Forestry and Woodland Strategies. Reviewing the Right Tree Right Place Guidance is a commitment in the National Planning Framework 4 Delivery Programme (2023-28) and Scotland’s Forestry Strategy Implementation Plan (2022-25).

- Woodland Carbon Code (WCC) – the WCC provides financial support and future income stream for woodland creation schemes that would not be financially viable without the additional support of carbon income.

- Woodland removal – the Scottish Government's Policy on Control of Woodland Removal & Implementation Guidance support planning authorities in assessing the impact of planning applications on the forestry resource. Together they provide a strong presumption in favour of protecting Scotland’s woodland resources. Woodland removal should be allowed only where it would achieve significant and clearly defined additional public benefits. In appropriate cases, a proposal for compensatory planting may form part of this balance.

- Improving resilience – one of the three key objectives in the Scottish Forestry Strategy is to “improve the resilience of Scotland’s forests and woodlands and increase their contribution to a healthy and high quality environment”. Scottish Forestry have engaged with a national-level stakeholder to consider how to best build resilient future forests, and have established a steering group with cross-sector representation to deliver this. A Resilience Action Plan is due to be published in 2024. This will ensure that Scotland’s Forests are able to mitigate, adapt, respond and recover from disturbances related to climate change, and attacks by pests and diseases.

- SBS DP Protected woodlands – NatureScot will establish a programme to enable protected woodlands to be brought into favourable condition with clear targets and a clear framework for decision making by the end of 2028.

- SBS DP Ancient woodlands – NatureScot will develop the new Register of Ancient Woodlands, to include locational data, a definition of the required ‘protected and restored’ condition of ancient woodlands, and a process for recording ancient woodlands that reach the required standard.

- SBS DP Deer cull targets – The Deer Management Round Table agreed to attain deer cull at level at which habitats and ecosystems can recover and regenerate, and where deer densities are maintained at sustainable levels. This is done by increasing the national cull by 25-30% sustained over several years; achieving densities of 5-8 deer per km2 in Cairngorms National Park; and low deer densities of around 2 deer per km2 where woodland regeneration is a priority and required to achieve the UKFS.

- SBS DP Deer management – by 2027, NatureScot, supported by Scottish Forestry and Forestry and Land Scotland will review the use of mechanisms to support effective and safe deer management in new and existing woodlands.

Blue carbon