International Development Fund - inclusive education programme: report

This report supports the development of the Scottish Government’s (SG) International Development Inclusive Education Programme, which will operate in Scotland’s International Development partner countries: Malawi, Rwanda, and Zambia.

Why invest in education for girls and young women?

To various extents, gender inequality persists in all countries (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, OECD, 2019). The education sector is no exception to this. In fact, inequalities and girls’ exclusion from education have wide ranging impacts, from limiting the individual’s employment prospects and higher rates of child marriage to reduced national growth and community stability, not to mention, the denial of one’s human rights (United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund - UNICEF, 2023a; Malala Fund, 2023). As such, investing in girls’ education is a high priority globally, with a large number of donors active within this area. For example, the Girls’ Education Challenge funded by the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO). This focus has produced significant progress in girls’ education in low- and middle-income countries over the last 50 years, with girls often having more completed years of schooling than their male counterparts (Centre for Global Development CGD, 2022). Nevertheless, the non-pharmaceutical interventions implemented to supress the spread of COVID had a particularly negative impact on girls, who were less likely to return to school following the school closures, and more likely to have experienced mental health issues, violence, and an increase in domestic chores, early childhood pregnancy and marriage (see for example, Institute of Development Studies - IDS, 2022 and World Bank, 2020b). Furthermore, there is evidence to suggest that the negative effects of the closures on girls will also be compounded by other intersectional factors, such as living with a disability and low socio-economic status (United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organisation - UNESCO, 2022). Therefore, there is a need for further investment in this area to ensure the gains of the last half century are not undone.

Why invest in education girls and young women in partner countries?

Following initial inter-governmental conversations between the Scottish Government and the governments of Malawi, Rwanda and Zambia to identify priority focus areas for support on Inclusive Education, a targeted needs analysis was conducted in SG partners countries, with the aim to identify areas where the respective education systems need support to improve inclusivity. In all contexts, education for girls and young women had shown significant signs of improvements in recent years. However, gender remains a multiplying factor when it intersects with other forms of disadvantage such as girls who also have a disability or come from a lower socio-economic background (UNESCO, 2022). Therefore, there is a clear need for investment in partner countries to support girls and young women from marginalised communities to access and remain in education. These needs are particularly acute at the higher levels of the system. A brief overview of the three contexts is detailed below.

Malawi

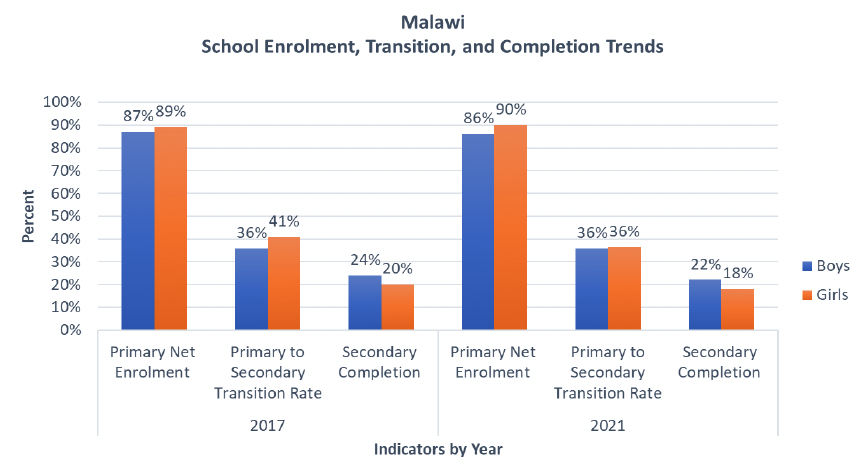

Source: Ministry of Education (MoE), 2021

In Malawi, girls have a slight advantage in terms of primary level enrolment and secondary level transition rates. However, this advantage does not continue through secondary school, with boys maintaining a 4-percentage point higher secondary completion rate between 2017 and 2021. This can be seen in figure 1. This trend seemingly continues and intensifies in tertiary education. However, a lack of recent data makes this difficult to understand the current situation. In 2011, the tertiary education enrolment gender parity index was 0.62, which suggests a further significant reduction in girls’ advantages, and in 2015, female gross enrolment in tertiary education was only 1%, half that of males (World Bank, 2023). There is also a lack of recent publicly available assessment data, particularly at higher levels of education. However, EGRA data from 2016 suggests that girls outperform boys academically (USAID, 2016). Therefore, it is likely that it is broader societal barriers, which inhibit girls transitioning through the Malawian education system.

For example, Malawi has the highest rates of child marriage in the world, with 12% of girls being married before they are 15 and 50% before they are 18 (Ministry of Gender, Children, Disability and Social Welfare - MoGCDSW, 2014). This point was further reinforced by the stakeholder consultations, where participants raised the issues of cultural norms and practices, such as early pregnancy, child labour or domestic duties, excluding girls from education at all levels. Other exclusionary issues raised in the consultation include the scarcity of spaces in secondary schools that are close to the girls’ homes, which creates the potential for a dangerous travel to gain access to the next stages of their education, poverty, and increasing responsibilities within the family. These factors combined not only create barriers for girls to enter or continue in their education, but also add to the family’s argument to keep daughters at home. Furthermore, whilst data on the impact of the Covid-19 school closures is insufficient, the information available suggests girls were particularly disadvantaged during this period, with reported increases in girl drop-outs and early pregnancies (40,000 increase) and child marriage (additional 12,995) (Institute of Development Studies - IDS, 2022). This highlights two areas of need within the Malawian education systems. Firstly, there is a clear need for investment at the higher levels of the education system, to address the barriers faced by girls and young women in terms of access and retention. The second area for action identified is in improved data practices, in order to improve the understanding of gender equity at higher levels in the system, which, in turn, will support evidence informed policy making.

Rwanda

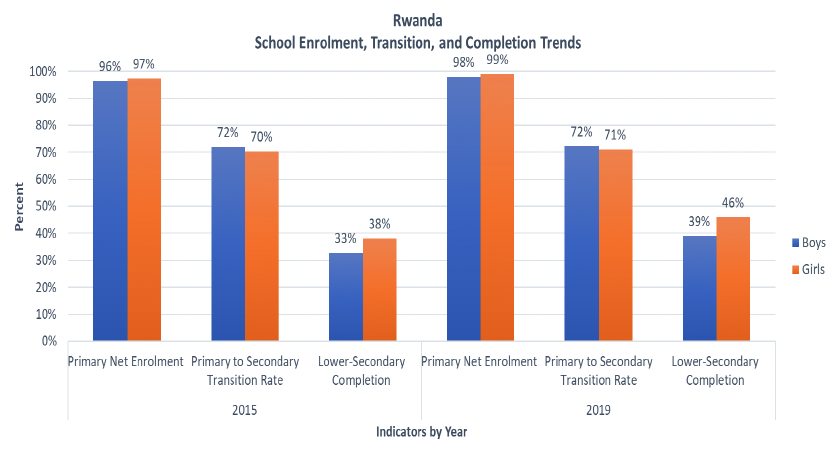

Source: NISR, 2021; MoE, 2018

In Rwanda, girls have an advantage in basic education. Figure 2 shows this well. Net enrolment in primary education is high for both sexes. However, girls' enrolment is higher, reaching 99% in 2019. Between 2015 and 2019, girls were 1 percentage point less likely to transition to secondary education. Nevertheless, if they did, they were significantly more likely to complete lower secondary level. For example, in 2019, 46% of girls completed lower- secondary school, compared to 39% of boys. Furthermore, whilst lower secondary completion has been rising in both sexes, the gap between boys and girls has been widening in favour of girls, growing 2 percentage points between 2015 and 2019.

There is less data available at the higher levels of education. However, the trend of a female educational advantage appears to continue. In the upper secondary level, between 2016 and 2018 girls maintained a higher net enrolment rate than boys, dropping from 24.3% to 23.3% for girls and 22.7% to 20.7% for boys (Ministry of Education - MoE, 2018). In 2016, the girls also had a higher transition rate to tertiary education than boys, with 47.5% and 46.9% of female and male learners transitioning respectively (MoE, 2018). Furthermore, whilst publicly available assessment data is scarce, EGRA data suggests that girls also outperform boys academically (United States Agency for International Development -USAID, 2018).

Nevertheless, disadvantage is multifaceted, and this high-level overview of the Rwandan education system does not account for instances where being female can further compound disadvantage. For example, adolescent girls in the poorest quintile of urban areas are more likely to be out of school than boys (36% compared to 22%) (Centre for Global Development - CGD, 2022). Furthermore, the evidence available from the impact of the Covid-19 closures suggest that the negative consequences were greater for those already marginalised. For example, households with lower socio-economic status struggled to send their children back to school due to the loss in income experienced from lockdowns and, for girls, the closures also led to early sexual debut and marriages, and increased teenage pregnancies and gender-based violence (FCDO, 2021). Therefore, there is a support need for girls’ and young women’s education in Rwanda to reduce the barriers faced by girls from marginalised group in accessing and remaining in education. Specifically, to address the impacts of the Covid closures, financial barriers are key area to target to support girls to return to the classroom (Oulo et al., 2021).

The focus of government gender policy is on increasing girls’ participation in Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) and science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) subjects, in order to increase employment skills (NISR, 2021). As such, any targeted support SG puts in place should also align with this approach and be targeted at the higher levels of education including TVET.

Zambia

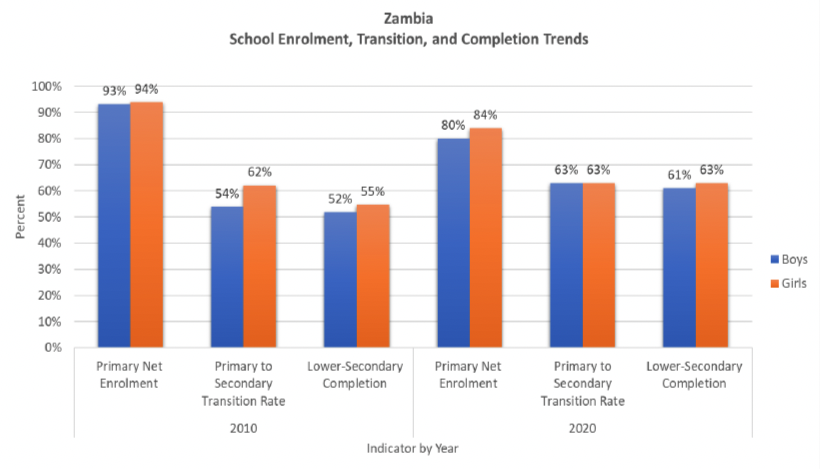

Source: MoE, 2010; MoE 2020

The Zambian education system provides free to access basic education, which was extended to the secondary level in 2022. The system is well balanced in terms of male and female enrolment patterns, with girls having a slight advantage. This is shown well in figure 3. In 2010 and 2020 girls had higher primary enrolment and completion rates than boys. In 2010 girls also had a higher transition rate from primary to lower-secondary school (62% compared to 54%), but in 2020 both 63% of boys and girls enrolled in primary school transitioned to secondary education. Furthermore, the government has introduced a range of policies targeted at supporting gender equity with education. These include heavy fines for those keeping children out of school (due to reasons such as child marriage); quotas for girls in technical schools; bursaries for girls; and a re-entry policy for girls who become pregnant. Nevertheless, there are still areas in which the government may benefit from support. For example, one such area is the latter issue of teenage pregnancy.

Whilst there is a policy in place to support girls to return to education post pregnancy, at the primary level only around half do and in 2018 69% of secondary school girls returned post pregnancy. Evidence from both Zambia and the wider the region suggest a key barrier to re-entry is cost (see for example, World Bank, 2020; Oulo et al., 2021; Jochim et al., 2022). As such, there is a case for targeted SG support to keep marginalised girls in education. This is especially true in the context of the adverse effects of the Covid-19 school closures, where, whilst exact figures are not available, reports suggest Zambia experienced an increase in girls dropping out and an increase in teenage pregnancy (see for example, World Bank, 2020b and Comprehensive Perl Archive Network - CPAN, 2021).

Building on the data limitations from the Covid closures, Zambian stakeholders also noted during the consultation process that they do not have access to gender disaggregated data more broadly. This creates challenges in monitoring the impact of policy and strategy on girls, and is an area SG could also provide support in.

Contact

Email: socialresearch@gov.scot

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback